Abstract

Increased potential for disease transmission among nest-mates means living in groups has inherent costs. This increased potential is predicted to select for disease resistance mechanisms that are enhanced by cooperative exchanges among group members, a phenomenon known as social immunity. One potential mediator of social immunity is diet nutritional balance because traits underlying immunity can require different nutritional mixtures. Here, we show how dietary protein–carbohydrate balance affects social immunity in ants. When challenged with a parasitic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae, workers reared on a high-carbohydrate diet survived approximately 2.8× longer in worker groups than in solitary conditions, whereas workers reared on an isocaloric, high-protein diet survived only approximately 1.3× longer in worker groups versus solitary conditions. Nutrition had little effect on social grooming, a potential mechanism for social immunity. However, experimentally blocking metapleural glands, which secrete antibiotics, completely eliminated effects of social grouping and nutrition on immunity, suggesting a causal role for secretion exchange. A carbohydrate-rich diet also reduced worker mortality rates when whole colonies were challenged with Metarhizium. These results provide a novel mechanism by which carbohydrate exploitation could contribute to the ecological dominance of ants and other social groups.

Keywords: ants, disease resistance, ecoimmunology, geometric framework, nutrition, social behaviour

1. Introduction

Social insects make up more than half of global insect biomass [1], an ecological dominance that has arisen in spite of inherent costs associated with group living. One such cost is the increased risk of parasite transmission among closely packed and closely related nest-mates [2]. It may be offset by increased per capita investment in immune function [3] and by group-level defences termed ‘social immunity’ [4,5]. Food availability is a likely mediator of social immunity. It is generally considered an important constraint on immune function [6] owing to the high maintenance costs of immune functions relative to other physiological costs [7]. Many studies have shown trade-offs between individual immunity and other fitness-enhancing functions that become more acute under starvation and caloric restriction treatments [8–10].

Both the quantity of food components and their relative availability can affect the nature and extent of immune responses [11–14], as well as a range of physiological and life-history traits [15]. If specific traits promoting immunity require different nutritional mixtures, then scarcity of particular dietary components should influence the relative costs of those different mechanisms promoting an organism's immune function [15,16]. Dietary protein (P) and carbohydrate (C), both their distinct and interactive effects, have shaped immune function [12,13,16] (reviewed in [17]) for a variety of solitary organisms. While protein nutrition can constrain immune response in honeybees [18], we know of no study investigating how diet macronutrient composition affects social immunity.

Here, we tested how dietary protein : carbohydrate (P : C) ratio affects social immunity in a tropical ant, Ectatomma ruidum, combatting the parasitic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae, a model pathogen for studying social immunity [19–22]. Ants have two prominent mechanisms for social immunity (for additional mechanisms, see [23,24]). Allogrooming is a time-intensive [25] activity where nest-mates clean each other's cuticle, reducing the number of fungal spores [20,26,27]. The metapleural gland, a structure unique to ants [28], secretes antibiotics that reduce spore viability [20,29–31]. Both allogrooming and metapleural gland production can thus lower infection rates of ant workers exposed to Metarhizium. As dietary P : C constrains many worker- and colony-level traits [32], including storage biochemistry [33], worker longevity [32] and possibly worker activity rates [34] (but see [35]), we predicted that lower dietary P : C ratios would increase nest-mate interaction frequency and, in turn, the benefits of social grouping after exposure to Metarhizium. Our results provide new insight into the social value of carbohydrate resource exploitation.

2. Material and methods

We conducted all work in June–July 2011, January 2012 and June–July 2012 on Barro Colorado Island, a lowland, seasonally wet forest in Lake Gatun of the Panama Canal. Ectatomma ruidum (subfamily Ectatomminae) is a ground-nesting ant with zero to four queens and approximately 10–150 workers per nest at this site; queenless nests are common. Colonies commonly consist of multiple nests. We excavated nests (58 in June 2011, 43 in January 2012 and 24 in June 2012) and maintained them in circular containers (18 × 8 cm) lined with Fluon and covered with mesh to prevent escape. In each container, we placed three nest chambers, which were 20 × 100 mm glass test tubes half-full of water at the base and stopped with cotton. We covered nest chambers with foil. We maintained colonies in a covered shelter at ambient understorey light, temperature and humidity.

(a). Nutrition effects on worker social immunity

In June 2011 and January 2012, we tested whether nutrition affects social immunity in worker groups. We reared colonies (all workers, pupae and larvae excavated from a nest; any queens were excluded) on isocaloric, semi-synthetic diets that differed only in P : C ratio (diet modified slightly from [36]; electronic supplementary material, table S1). We used two P : C ratios (1P : 3C and 3P : 1C) that are readily consumed by E. ruidum [37], differentially affect colony growth and worker biochemistry [33], and bracket the P : C ratio collected by E. ruidum in feeding trials in the field [37]. We assigned 52 colonies (26 in June 2011, 26 in January 2012) to diet treatment after ordering them by size (sum of principal components from analysis of worker, pupa and larva numbers); we split five nests with more than 60 workers (three in June 2011, two in January 2012) and assigned halves to different diets. We reared colonies for 18 days by providing approximately 1 g blocks of food every second day (ad lib feeding), and quantified food dry mass loss as in [33]. We also counted and removed dead workers every 2 days.

For survival assays, we measured responses of solitary and social ant groupings to treatment with M. anisopliae (strain KVL02-73 collected at this site [38]). After the 18-day diet manipulation, we created one-ant (solitary ants) or five-ant (worker groups) sets from each colony. In June 2011, we assigned 10 solitary ants and two worker groups per colony to a Metarhizium treatment; in January 2012, we assigned five solitary ants and one worker group per colony to a Metarhizium treatment, and the same number to a control treatment. The Metarhizium treatment consisted of applying to the thorax of each ant 0.5 µl of an LD50 concentration (6.92 × 10−6, determined at the outset) of Metarhizium spores suspended in 0.05% Triton-X. Control ants received 0.5 µl of 0.05% Triton-X. For treatment, we held ants with sterilized forceps and applied the dose to the dorsal surface of the thorax. We housed solitary ants and worker groups in Petri dishes (3 cm diameter) with moistened cotton (re-moistened every 2 days) and checked daily for mortality over 14 days (in June 2011) or 22 days (in January 2012). We removed dead ants, sterilized them (with 1% NaClO), placed them on filter paper and monitored them for 7 days for signs of Metarhizium infection (characteristic conidia growth that occurs within 2–3 days).

(b). Allogrooming effects on nutrition-related social immunity

In June 2012, we assessed whether diet affects allogrooming, an established mechanism of social immunity in ants [20]. We assigned 24 colonies to either the 1P : 3C or 3P : 1C diet, as above. After an 18-day rearing period, we created solitary ant and worker group sets, and treated them with either Metarhizium or the control Triton-X solution. We then immediately began assaying grooming behaviour after Walker & Hughes [39]. We observed behaviour for 30 s periods at every 10 min for 60 min, as most grooming occurs immediately after solution application (A.D.K. & A.J.B. 2011, personal observation; see also [26]). We recorded the number of antennal self-grooming and allogrooming events. Behaviours that occurred for more than a 5 s period were split into multiple events.

(c). Metapleural gland effects on nutrition-related social immunity

In January 2012, we tested whether secretions from the metapleural gland (a specialized gland on the thorax of ants that produces antibiotic secretions) influences diet-related immunity. To do this, we reared 12 colonies on either the 1P : 3C or 3P : 1C diet for 18 days. We then blocked the metapleural gland (using nail polish) on 10 ants per colony, created five solitary ant or one worker group sets and treated all ants with Metarhizium as described above. We assessed survivorship as above. We used workers sampled from field colonies to show that blocking metapleural glands per se did not affect survivorship (Cox proportional hazards: L-R χ2 = 0.087, d.f. = 1, p = 0.762, n = 40).

(d). Nutrition effects on colony-level immunity

In June 2011 and January 2012, we tested how nutrition affects colony-level immunity, and whether nutritional immunity depended on the presence of larvae in colonies. Given that nutritional feedbacks between workers and larvae influence P : C regulation in ant colonies [32], we predicted that larval presence would enhance nutritional effects on colony immunity.

For this test, we used 16 colonies in June 2011 and 10 in January 2012. We assigned colonies (blocked by size as above) to the 1P : 3C or 3P : 1C diet and removed larvae from half of the colonies in each treatment; we removed and returned larvae for control colonies. We reared colonies for 21 days. During the rearing period, we challenged colonies with Metarhizium by placing headless ant corpses covered in Metarhizium spores in each nest every 2 days. We used this approach to challenge colonies (rather than direct application to workers of spores in solution, as above) because we wanted to sufficiently challenge colonies to test for differences among diet treatments; spore-covered corpses could be added at regular intervals, whereas periodic solution application to workers would have considerably disturbed colonies. We counted the number of dead ants in each colony (easily distinguishable from headless ant additions) every 2 days and monitored each for signs of infection (as above).

(e). Statistical analyses

We analysed total carbohydrate and protein intake using the restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) method, with year of the study as a random factor and diet as a fixed factor. We analysed effects of diet and social grouping (fixed effects) on worker survivorship using the Cox proportional hazards model (year was included as a random factor). We analysed colony-level effects of nutrition on Metarhizium resistance using REML. The response variable was number of dead workers divided by number of initial workers in the colony per day; explanatory variables were diet and Metarhizium treatment (fixed effects), and year of study was included as a random effect. We analysed grooming behaviour using a repeated-measure ANOVA with diet and Metarhizium treatment as fixed factors. We did not include colony as a random factor in this analysis because some colonies had too few workers to allocate to multiple treatments. For these small colonies, worker groups were randomly assigned to treatments. We tested whether ant mortality was associated with evidence of Metarhizium infection using a likelihood ratio test. We conducted all analyses using JMP v. 8.0.1.

3. Results

(a). Nutrition effects on worker social immunity

Colonies consumed similar amounts of food in the two diet treatments, resulting in approximately 3× higher carbohydrate intake and approximately 3× lower protein intake for colonies on the lower-P : C diet versus those on the higher-P : C diet (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

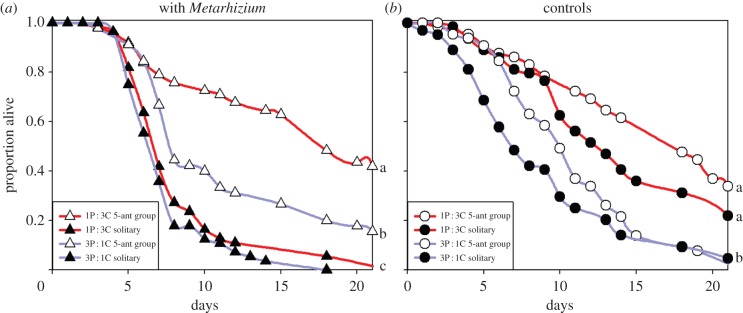

A high-carbohydrate diet enhanced social immunity in workers (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). When workers were challenged with Metarhizium (figure 1a), both the lower-P : C diet (Cox proportional hazards: L-R χ2 = 15.886, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001, n = 745) and social grouping (L-R χ2 = 86.871, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001) increased worker survivorship. Importantly, there was a significant diet-by-social grouping interaction (L-R χ2 = 10.499, d.f. = 1, p = 0.001), as the 1P : 3C diet increased worker survivorship in worker groups more than for solitary ants. We conducted Metarhizium challenge in both 2011 and 2012; survivorship differed between the two replicates of the experiment (main effect of year: L-R χ2 = 24.748, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001), but there was no significant year-by-diet-by-social grouping interaction (L-R χ2 = 0.689, d.f. = 1, p = 0.407) as the 1P : 3C diet enhanced social immunity in workers in both years. We included ants that were not challenged with Metarhizum (controls) in 2012. With these data, we found that in the absence of Metarhizium challenge (figure 1b), the lower-P : C diet (L-R χ2 = 36.143, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001, n = 258) and social grouping (L-R χ2 = 5.541, d.f. = 1, p = 0.019) increased worker survivorship, but there was no significant diet-by-social grouping interaction (L-R χ2 = 0.081, d.f. = 1, p = 0.777).

Figure 1.

The effects of diet composition, social grouping and challenge from the Metarhizium fungal parasite on ant worker survivorship. Ants are from colonies maintained on either a 1 protein (P) : 3 carbohydrate (C) ratio diet (red lines) or a 3P : 1C (blue lines) diet. Data in panel (a) are from 2011 and 2012. Data in panel (b) are from 2012 only. (a) Survivorship for Metarhizium-challenged ants when alone (solitary) or in 5-ant worker groups. (b) Survivorship for ants not facing Metarhizium challenge. Different lower-case letters indicate survival curve differences at p < 0.01 in pairwise comparisons using Kaplan–Meier survival tests.

In Metarhizium treatments, fewer dead ants showed signs of Metarhizium infection in worker groups (approx. 44%) than in the solitary ant setting (approx. 93%; χ2 = 66.4, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001), and evidence of infection did not differ significantly with diet (χ2 = 1.06, d.f. = 1, p = 0.303). About 5% of ants showed signs of Metarhizium infection in control groups. This probably represents a natural infection level owing to our use of ants recently collected from the field. It does not affect our conclusions because our experiments explicitly compared these control ants with ants treated with Metarhizium.

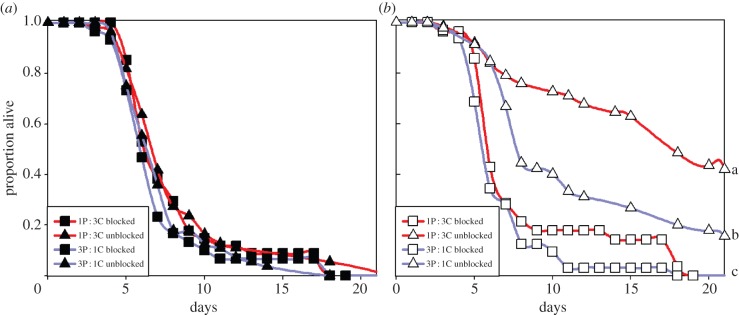

(b). Metapleural gland effects on nutrition-related social immunity

Blocking metapleural glands eliminated effects of diet composition and worker grouping on survivorship for ants facing Metarhizium challenge (figure 2). Survivorship for solitary ants with blocked metapleural glands was similar to levels in solitary ants with unblocked glands, regardless of diet (figure 2a; Cox proportional hazards: blocking: L-R χ2 = 0.682, d.f. = 1, p = 0.409, n = 175; diet: L-R χ2 = 1.632, d.f. = 1, p = 0.201; blocking-by-diet: L-R χ2 = 0.007, d.f. = 1, p = 0.933). By contrast, blocking metapleural glands significantly reduced survivorship in worker groups, particularly for ants reared on the 1P : 3C diet (figure 2b; blocking: L-R χ2 = 40.004, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001, n = 167; diet: L-R χ2 = 13.682, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001; blocking-by-diet: L-R χ2 = 3.862, d.f. = 1, p = 0.049). An analysis restricted to ants with blocked metapleural glands showed that neither diet nor worker grouping affected survivorship under these conditions (diet: L-R χ2 = 2.249, d.f. = 1, p = 0.134; grouping: L-R χ2 = 0.060, d.f. = 1, p = 0.807). Survivorship for Metarhizium-challenged ants in solitary conditions with blocked glands (figure 2a) did not differ significantly from survivorship for challenged, solitary ants with unblocked glands (blockage: L-R χ2 = 0.682, d.f. = 1, p = 0.409), indicating that gland blockage itself did not affect survivorship.

Figure 2.

Effect of blocking metapleural glands on survivorship of workers exposed to the Metarhizium parasite and reared on either a 1 protein (P) : 3 carbohydrate (C) diet (red) or a 3P : 1C (blue) diet in either (a) solitary or (b) five-ant worker groups. Different lower-case letters indicate survival curves differences at p < 0.01 in pairwise comparisons using Kaplan–Meier survival tests.

Almost all Metarhizium-treated ants with blocked metapleural glands showed evidence of Metarhizium infection (solitary 87.4%, social 86.6%), and evidence of infection did not differ significantly with diet (p > 0.75). Evidence of Metarhizium infection did not depend on metapleural gland blockage for solitary ants (χ2 = 0.010, d.f. = 1, p = 0.920); in worker groups, evidence of Metarhizium infection was significantly higher for ants with blocked metapleural glands than it was for ants without blocked glands (χ2 = 86.428, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001).

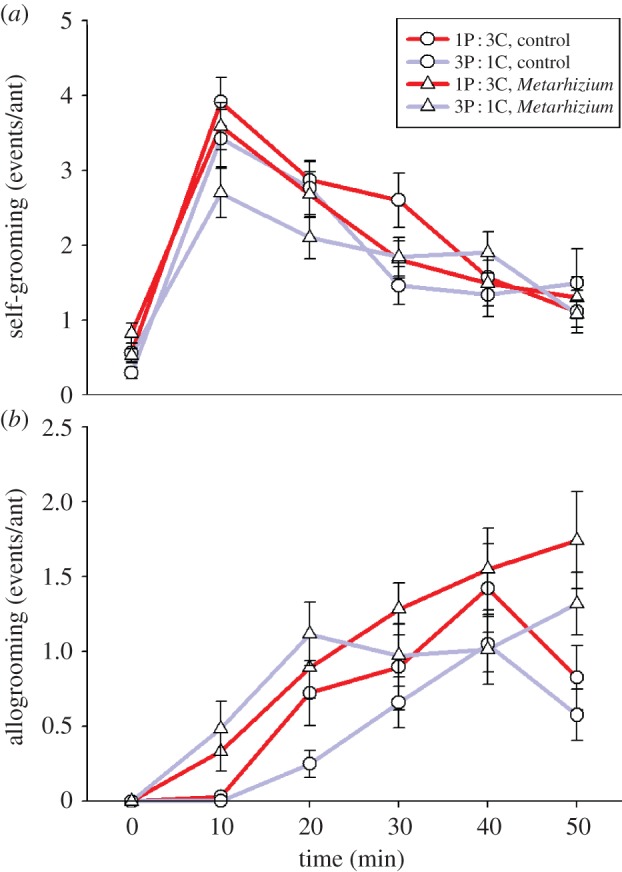

(c). Allogrooming effects on nutrition-related social immunity

We found little evidence for diet effects on grooming behaviour (figure 3). Allogrooming frequency was significantly higher in Metarhizium-challenged ant groups than in control groups (repeated-measures ANOVA: F5,66 = 3.128, p = 0.014), but it did not depend on rearing diet (F5,66 = 0.762, p = 0.580). Self-grooming frequency was not significantly affected by either Metarhizium challenge (F5,71 = 2.32, p = 0.052) or rearing diet (F5,71 = 1.053, p = 0.393), and there was no significant Metarhizium-by-diet interaction (F5,71 = 1.803, p = 0.123). Allogrooming frequency was significantly higher in Metarhizium-challenged ant groups (F5,66 = 3.128, p = 0.014) but did not depend on rearing diet (F5,66 = 0.762, p = 0.580) and there was no significant Metarhizium-by-diet interaction (F5,66 = 0.796, p = 0.556).

Figure 3.

Frequency of grooming behaviours in groups of five ants that were reared on either a 1 protein (P) : 3 carbohydrate (C) diet or a 3P : 1C diet and either were or were not challenged with the parasitic fungus M. anisopliae. Response variables are (a) antennal self-grooming or (b) nest-mate grooming (allogrooming) events during 30 s observation periods. Behaviours that occurred for more than a 5 s period were split into multiple events. Neither self-grooming nor allogrooming was significantly affected by rearing diet.

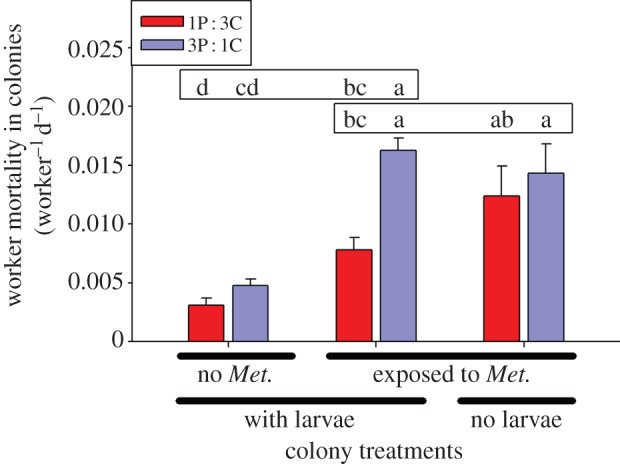

(d). Nutrition effects on colony-level immunity

A high-carbohydrate diet also enhanced immunity in whole colonies (figure 4). Regular addition of spore-covered corpses to colonies (Metarhizium treatment) increased worker mortality more in the 3P : 1C diet than in the 1P : 3C diet (figure 4; diet-by-Metarhizium: F1,71 = 11.339, p = 0.001). There was also a significant effect of larval presence on diet-related immunity (figure 4; diet-by-larvae: F1,41 = 4.167, p = 0.047). Most (77.4%) workers that died during the experiment showed signs of Metarhizium infection, and the likelihood of infection in dead workers did not depend on diet treatment or larval presence (p > 0.56). Metarhizium-challenged colonies had higher food consumption than did control colonies, and food consumption was particularly high for Metarhizium-challenged colonies with larvae on the high-protein diet (figure S1).

Figure 4.

Effect of M. anisopliae challenge and larval presence on worker mortality in colonies fed either a 1 protein (P) : 3 carbohydrate (C) diet (red bars) or a 3P : 1C (blue bars) diet. Worker mortality (number of dead workers divided by number of initial workers in the colony per day) values are least-square means with random variable year included in the model. Two targeted comparisons were made: among colonies with larvae (exposed or not exposed to Metarhizium) and among colonies exposed to Metarhizium (with or without larvae). Colonies with larvae exposed to Metarhizium were used in both comparisons. Different letters indicate p < 0.05 in Tukey's HSD post hoc test for each comparison (upper box, ±Metarhizium comparison; lower box, ±larvae comparison).

4. Discussion

We show for the first time that diet macronutrient composition affects immunity gains that arise from social grouping. When challenged with a pathogenic fungus (M. anisopliae), E. ruidum ants in worker groups survived longer when reared on a high-carbohydrate (1P : 3C) diet than did those reared on a high-protein (3P : 1C) diet, while solitary ants had similarly low survival rates when reared on either diet. These results do not simply reflect a general response to a low-quality diet because benefits from the high-carbohydrate diet only emerged in worker groups; there was no significant effect of diet in solitary conditions. In addition, a carbohydrate-rich diet reduced worker mortality rates when whole colonies were challenged with Metarhizium. Together, these results provide a novel mechanism by which nutrient balance can affect social groups and suggest an evolutionary advantage of carbohydrate exploitation by social insects.

As implied by the adage ‘feed a cold, starve a fever’, bulk food availability is generally considered an important mediator of immunity [6]. Immune functions have high metabolic costs relative to other physiological systems [7], and many studies have used starvation or caloric restriction treatments to show how bulk energy availability impairs individual disease resistance [8–10]. However, traits underlying immunity can require different nutritional mixtures and, as a result, the extent and nature of immune responses can depend on the relative availability of dietary components [12,18], including P : C balance [16,17]. Our results provide the first evidence that the immune consequences of nutrient balance can extend to social groups and may emerge as a consequence of nest-mate interactions.

Antibiotics played a key role in this nutrition-related social immunity. Blocking metapleural glands, the main source of antibiotic secretions, eliminated both diet and social grouping effects on immunity (figure 2), and increased the likelihood that cadavers showed signs of Metarhizium infection. Metapleural gland function can account for 13–20% of basal metabolic rate [40], so carbohydrate scarcity in a high-protein diet could reduce metabolite allocation to metapleural glands or exact trade-offs on other metabolic functions. Note that Metarhizium resistance does not depend on the metapleural gland in some ant species [23,24], and thus constraints on metapleural secretions will not explain nutrition-related social immunity in all ants.

By contrast, our results do not support the hypothesis that increases in energetically expensive allogrooming result from a higher-carbohydrate diet. Even though carbohydrate-rich diets can lead to higher metabolic rates [41], and possibly higher activity rates in insects, we found no evidence for nutritional effects on grooming frequency. Note, however, that we only observed grooming behaviour for 50 min after treatment (as in [26]); it is possible that significant grooming frequency differences among treatments could emerge with a longer observation period.

Results from the whole-colony experiment (figure 4) also revealed the benefits of a high-carbohydrate diet to immune function. These results suggest that colonies can buffer isolated effects of high dietary protein or Metarhizium challenge, but the effect of these factors in combination can overwhelm colony resistance and lead to higher worker mortality rates. We also found that removing larvae from colonies eliminated diet effects on worker mortality rates when colonies were challenged with Metarhizium (figure 4). Larvae, which (unlike workers) can digest protein, can serve to dampen effects of nutritionally imbalanced diets for ants [32]. Our results suggest that these protein digestion benefits may improve worker immunity in colonies on high-carbohydrate diets.

Our results identify a neglected component to the story of the rise of sociality as represented by eusocial insects [42]. The diversification of the ants is closely tied to the rise of angiosperms [43], which gave ants access to a particular nutrient (carbohydrates) and a resource (‘honeydew’) that they could exploit, farm and dominate [44]. Carbohydrates have been suggested as a mechanism for maintaining the particularly high ant abundances in tropical canopies [45] owing to changes in territorial behaviour [44,34], worker longevity [32,35,33] and colony growth [46]. Our results suggest that readily available carbohydrates, by fuelling the expensive metapleural glands, also enhanced per capita immune function. Such an added benefit may have been crucial in allowing more ants to live together in tightly confined spaces. More generally, enhanced social immunity on a high-carbohydrate diet provides a novel mechanism by which carbohydrate exploitation could facilitate the evolution of social behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We thank Callum Kingwell for help with data collection, and the staff of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute on Barro Colorado Island for logistical support.

Data accessibility

Data are available through the Dryad Digital Repository.

Funding statement

Financial support was provided by a grant from the National Science Foundation of the United States (DEB 0842038 to A.D.K. and M.K., and REU 1214433 to A.D.K.).

References

- 1.Wilson EO, Hölldobler B. 2005. The rise of the ants: a phylogenetic and ecological explanation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7411–7414 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0505858102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid-Hempel P. 1998. Parasites in social insects. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans JD, Spivak M. 2010. Socialized medicine: individual and communal disease barriers in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103, S62–S72 (doi:10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cremer S, Armitage SAO, Schmid-Hempel P. 2007. Social immunity. Curr. Biol. 17, R693–R702 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson-Rich N, Spivak M, Fefferman NH, Starks PT. 2009. Genetic, individual, and group facilitation of disease resistance in insect societies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 54, 405–423 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demas G, Greives T, Chester E, French S. 2012. The energetics of immunity: mechanisms mediating trade-offs in ecoimmunology. In Ecoimmunology (eds Demas GE, Nelson RJ.), pp. 259–296 New York, NY: Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid-Hempel P. 2005. Evolutionary ecology of insect immune defenses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 50, 529–551 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130420) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C. 2000. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos 88, 87–98 (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siva-Jothy MT, Thompson JJW. 2002. Short-term nutrient deprivation affects immune function. Physiol. Entomol. 27, 206–212 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-3032.2002.00286.x) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayres JS, Schneider DS. 2009. The role of anorexia in resistance and tolerance to infections in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000150 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith VH, Holt RD. 1996. Resource competition and within-host disease dynamics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 386–389 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)20067-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KP, Cory JS, Wilson K, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ. 2006. Flexible diet choice offsets protein costs of pathogen resistance in a caterpillar. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 823–829 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3385) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Povey S, Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Lee KP, Wilson K. 2009. Can the protein costs of bacterial resistance be offset by altered feeding behavior? J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 437–446 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01499.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponton F, Lalubin F, Fromont C, Wilson K, Behm C, Simpson SJ. 2011. Hosts use altered macronutrient intake to circumvent parasite-induced reduction in fecundity. Int. J. Parasitol. 41, 43–50 (doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. 2012. Nature of nutrition: a unifying framework from animal adaptation to human obesity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, Wilson K. 2011. Macronutrient balance mediates trade-offs between immune function and life history traits. Funct. Ecol. 25, 186–198 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01766.x) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponton F, Wilson K, Cotter SC, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ. 2011. Nutritional immunology: a multi-dimensional approach. PLoS Pathog. 7, 1002223 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002223) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alaux C, Ducloz F, Crauser D, Le Conte Y. 2010. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 6, 562–565 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosengaus RB, Maxmen AB, Coates LE, Traniello JFA. 1998. Disease resistance: a benefit of sociality in the dampwood termite Zootermopsis angusticollis (Isoptera: Termopsidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 44, 125–134 (doi:10.1007/s002650050523) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes WOH, Eilenberg J, Boomsma JJ. 2002. Trade-offs in group living: transmission and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1811–1819 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugelvig LV, Cremer S. 2007. Social prophylaxis: group interaction promotes collective immunity in ant colonies. Curr. Biol. 17, 1967–1971 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konrad M, et al. 2012. Social transfer of pathogenic fungus promotes active immunisation in ant colonies. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001300 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graystock P, Hughes WOH. 2011. Disease resistance in a weaver ant, Polyrhachis dives, and the role of antibiotic-producing glands. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 2319–2327 (doi:10.1007/s00265-011-1242-y) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tragust S, Mitteregger B, Barone V, Konrad M, Ugelvig LV, Cremer S. 2013. Ants disinfect fungus-exposed brood by oral uptake and spread of their poison. Curr. Biol. 23, 76–82 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. 1990. The ants. Cambridge, MA: Belknap [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker TN, Hughes WOH. 2009. Adaptive social immunity in leaf-cutting ants. Biol. Lett. 5, 446–448 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reber A, Purcell J, Buechel SD, Burj P, Chapuisat M. 2011. The expression and impact of antifungal grooming in ants. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 954–964 (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02230.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yek SH, Mueller UG. 2011. The metapleural gland of ants. Biol. Rev. 86, 774–791 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00170.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bot ANM, Ortius-Lechner D, Finster K, Maile R, Boomsma JJ. 2002. Variable sensitivity of fungi and bacteria to compounds produced by the metapleural glands of leaf-cutting ants. Ins. Soc. 49, 363–370 (doi:10.1007/PL00012660) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes WOH, Bot ANM, Boomsma JJ. 2010. Caste-specific expression of genetic variation in the size of antibiotic-producing glands of leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 609–615 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1415) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Marin H, Zimmerman J, Rehner S, Wcislo W. 2006. Active use of the metapleural glands by ants in controlling fungal infection. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1689–1695 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3492) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dussutour A, Simpson SJ. 2009. Communal nutrition in ants. Curr. Biol. 19, 740–744 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay AD, Shik JZ, Van Alst A, Miller KA, Kaspari M. 2012. Diet composition does not affect ant colony tempo. Funct. Ecol. 26, 317–323 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01944.x) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grover CD, Kay AD, Monson JA, Marsh TC, Holway DA. 2007. Linking nutrition and behavioural dominance: carbohydrate scarcity limits aggression and activity in Argentine ants. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 2951–2957 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kay AD, Zumbusch TB, Heinen JL, Marsh TC, Holway DA. 2010. Nutrition and interference competition have interactive effects on the behavior and performance of Argentine ants. Ecology 91, 57–64 (doi:10.1890/09-0908.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dussutour A, Simpson SJ. 2008. Description of a simple synthetic diet for studying nutritional responses in ants. Ins. Soc. 55, 329–333 (doi:10.1007/s00040-008-1008-3) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook SC, Behmer ST. 2010. Macronutrient regulation in the tropical terrestrial ant, Ectatomma ruidum: a field study. Biotropica 42, 135–139 (doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00616.x) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes WOH, Petersen K, Ugelvig L, Pedersen D, Thomsen L, Poulsen M, Boomsma JJ. 2004. Density-dependence and within host competition in a semelparous parasite of leaf-cutting ants. BMC Evol. Biol. 4, 45 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-45) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker TN, Hughes WOH. 2011. Arboreality and the evolution of disease resistance in ants. Ecol. Entomol. 36, 588–595 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2011.01312.x) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poulsen M, Bot ANM, Nielsen MG, Boomsma JJ. 2002. Experimental evidence for the costs and hygienic significance of the antibiotic metapleural gland secretion in leaf-cutting ants. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 52, 151–157 (doi:10.1007/s00265-002-0489-8) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanotto FP, Gouveia SM, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, Calder PC. 1997. Nutritional homeostasis in insects: is there a mechanism for increased energy expenditure during carbohydrate overfeeding? J. Exp. Biol. 200, 2437–2448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson EO. 2012. The social conquest of Earth. New York, NY: Liveright [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreau C. 2006. Phylogeny of the ants: diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science 312, 101–104 (doi:10.1126/science.1124891) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson DW. 1997. The role of resource imbalances in the evolutionary ecology of tropical arboreal ants. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 61, 153–181 (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1997.tb01785.x) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davidson DW, Cook SC, Snelling RR, Chua TH. 2003. Explaining the abundance of ants in lowland tropical rainforest canopies. Science 300, 969–972 (doi:10.1126/science.1082074) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilder SM, Holway DA, Suarez AV, Eubanks MD. 2011. Macronutrient content of plant-based food affects growth of a carnivorous arthropod. Ecology 92, 325–332 (doi:10.1890/10-0623.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available through the Dryad Digital Repository.