Abstract

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a therapeutic product of recombinant DNA technology and it has been in clinical use as stimulator of erythropoiesis over the last two decades. Identification of EPO and its receptor (EPOR) in the cardiovascular system expanded understanding of physiological and pathophysiological role of EPO. In experimental models of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders, EPO exerts protection by either preventing apoptosis of cardiac myocytes, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, or by increasing endothelial production of nitric oxide. In addition, EPO stimulates mobilization of progenitor cells from bone marrow thereby accelerating repair of injured endothelium and neovascularization. A novel signal transduction pathway involving EPOR - β-common heteroreceptor is postulated to enhance EPO-mediated tissue protection. A better understanding of the role of β-common receptor signaling as well as development of novel analogues of EPO with enhanced non-hematopoietic protective effects may expand clinical application of EPO in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders.

Keywords: Erythropoietin, endothelium, eNOS, Akt

I. Introduction

The humoral regulation of erythropoiesis was identified more than 50 years ago (Bonsdorff and Jalavisto, 1948). Studies on erythropoietin (EPO) have been severely restricted, due to its circulating levels being only picomolar, until EPO was purified for the first time in 1977 from human urine (Miyake et al., 1977) and the amino acid sequence of human urinary EPO was characterized (Lai et al., 1986). EPO is a member of the class I family of cytokines and is mainly synthesized and secreted by the kidney (Jelkmann, 1992). The ability of EPO to stimulate erythropoiesis expanded clinical application of recombinant EPO to patients suffering from anemia and chronic kidney disease. To date, recombinant EPO is the most successful biotechnology drug and indeed is the world’s largest selling biopharmaceutical. EPO mediates erythropoiesis by binding to its specific receptor, EPO-receptor (EPOR), expressed on the surface of immature erythroblasts (Noguchi et al., 1991). Studies over the last decade have demonstrated that EPO and EPOR are expressed in a number of cell types including those within the cardiovascular and nervous system, suggesting that the effects of EPO extend beyond regulation of erythropoiesis.

In the cardiovascular system, EPO exerts its effects on cardiac as well as the vascular tissues. EPO and EPOR are expressed in cardiomyocytes, vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (Anagnostou et al., 1994; Ammarguellat et al., 1996; Brines and Cerami, 2005). It is important to note that high doses are required to observe EPO-induced tissue protection, in comparison to doses of EPO required for hematopoietic effects (Anagnostou et al., 1994; Ammarguellat et al., 1996; Brines and Cerami, 2005). Based on the existing studies with these high doses, a tangential paradigm evolved. On one hand, protective effects of EPO and the underlying mechanisms were elucidated in cardiovascular and neurological system, prompting initiation of clinical trials in patients with myocardial infarction, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and acute stroke. In contrast, adverse events associated with EPO therapy were identified, due to its pleiotropic effects mainly in the cardiovascular system including hypertension, thrombosis and augmented tumour angiogenesis. In this review, the present understanding of the beneficial and detrimental cardiovascular effects of EPO will be discussed.

II. Pharmacokinetics of Erythropoietin

A. Recombinant Human Erythropoietin

EPO was produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells by recombinant DNA technology (Sasaki et al., 1987; Sasaki et al., 1988). Following isolation of the human erythropoietin gene (Jacobs et al., 1985; Lin et al., 1985), it was inserted into and expressed by cultured mammalian cells, which are capable of synthesizing unlimited quantities of the hormone. Epoetin alfa, epoetin beta, and epoetin gamma are analogues of recombinant human EPO (rhEPO) derived from a cloned human erythropoietin gene, licensed by international regulatory bodies to stimulate erythropoiesis. All have the same 165 amino acid sequence with a molecular weight of 30,400 daltons and have the same pharmacological actions as native EPO (Jelkmann, 1992). After intravenous administration, epoetin is distributed in a volume comparable to the plasma volume. Epoetin plasma concentrations decay at a much slower rate after subcutaneous than intravenous administration (Table 1). Between epoetin alfa and epoetin beta exhibit some differences in their pharmacokinetic profiles, such as elimination half-life, due to differences in glycosylation pattern (Table 1) (Storring et al., 1998). Biological activity of EPO in vivo is abolished when EPO is deglycosylated, suggesting that the carbohydrate moiety is essential to prevent degradation and to delay clearance of EPO from the circulation (Takeuchi and Kobata, 1991).

Table 1.

Molecular characterization and elimination half-live of EPO and its analogues.

| Drug | Molecule structure

|

Route of administration

|

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | Glycosylation type | Number of sialic acid | Intravenous | Subcutaneous | ||

| Epoetin alpha | 30,400 daltons | 3 N-linked oligosaccharide chains | 10-14 | 4-8 hours | 24 hours | (McMahon et al., 1990; Halstenson et al., 1991; Macdougall et al., 1991) |

| Epoetin beta | 30,400 daltons | 3 N-linked oligosaccharide chains | 10-14 | 4-10 hours | 13-28 hours | (McMahon et al., 1990; Halstenson et al., 1991; Macdougall et al., 1991) |

| Darbepoetin alpha (NESP) | 37,100 daltons | 5 N-linked oligosaccharide chains | 22 | ~25 hours | ~50 hours | (Macdougall et al., 1999; Egrie and Browne, 2001; Egrie et al., 2003; Macdougall et al., 2007) |

| CERA | ~ 60,000 daltons | 30 kDa methoxy-polyethylene glycol polymer chain | 10-14 | ~134 hours | ~139 hours | (Macdougall and Eckardt, 2006; Locatelli et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2007) |

Normal serum concentrations of EPO for individuals with normal hematocrit range from 4-27 mU/mL but EPO levels can be increased 100-1000 times the normal serum EPO concentration in response to hypoxia and anemia (Jelkmann, 1992). Subcutaneous administration of a single 600 U/kg dose of epoetin alfa to healthy volunteers produced a peak serum concentration of over 1000 mU/mL after 24 hours (Ramakrishnan et al., 2004). Furthermore, it is important to consider differences in pharmacokinetic profile of rhEPO between human, dog, rat, and mouse for achieving the desired therapeutic effects with EPO. Indeed, the total body clearance of EPO increases in the order human = dog < rat ≪ mouse (Egrie et al., 1986; Bleuel et al., 1996).

B. New Generations of Erythropoietin-Related Drugs

1. NESP

The first-generation erythropoiesis stimulating agents were succeeded by the development and production of longer-acting EPO analogues. EPO is known to be desialylated in vivo, cleared from plasma, and is bound to galactose receptors in the liver (Egrie et al., 1993). Thus, there is a direct relationship between the amount of sialic acid-containing carbohydrates, plasma half-life, and in-vivo biological activity, and an inverse relationship with receptor affinity (Jelkmann, 1992; Egrie et al., 1993; Egrie and Browne, 2001). A second-generation NESP (darbepoetin) was created to test the hypothesis that an analogue with more sialic acid–containing oligosaccharides than EPO would have an extended circulating half-life and thereby an increased in vivo biological activity (Macdougall et al., 1999; Egrie et al., 2003). When compared with rhEPO, darbepoetin is a hyperglycosylated rhEPO analog with two extra carbohydrate chains with more sialic acid (Table 1) and has a molecular weight of 37,100 daltons (Macdougall, 2001). The amino acid sequence differs from that of native human EPO at five positions (Macdougall, 2001). Darbepoetin has a threefold longer circulating half-life than rhEPO (Table 1), and due to the pharmacokinetic differences, the relative potency of the two molecules varies as a function of the dosing frequency. Darbepoetin alfa is 3.6-fold more potent than rhEPO in increasing the hematocrit of normal mice when each is administered thrice weekly, but when the administration frequency is reduced to once weekly, darbepoetin alfa is approximately 13-fold higher in vivo potency than rhEPO (Macdougall, 2001; Egrie et al., 2003).

Epoetin and darbepoetin bind to the EPO receptor to induce signal transduction by the same intracellular molecules as native EPO. However, differences in the glycosylation pattern lead to variations in the pharmacodynamic profiles. Darbepoetin has approximately four-fold lower EPO receptor binding activity than rhEPO despite higher potency. The apparent paradox is explained by the counteracting effects of sialic acid containing carbohydrate on clearance (Egrie et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2004).

2. CERA

More recently, a third-generation EPO-related molecule has been manufactured called continuous EPO receptor activator (CERA; methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta), which was created by inserting a single 30 kDa polymer chain into the EPO molecule (Macdougall and Eckardt, 2006). The elimination half-life of CERA in humans is considerably increased to about 130 hours and is comparable after intravenous or subcutaneous administrations (Table 1) (Macdougall et al., 2006). Furthermore, CERA at up to once monthly intervals sustains and maintains sustained and stable control of hemoglobin levels (Locatelli et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2007).

III. Signal Transduction by Erythropoietin

Survival, proliferation and differentiation of red blood cells by EPO are mediated by activation of the homodimeric EPO receptor, EPOR, which belongs to the cytokine receptor superfamily (Richmond et al., 2005). Binding of EPO to the erythrocytic EPOR induces a conformational change of the homodimeric-EPOR and triggers Janus protein tyrosine kinase 2 (Jak2) phosphorylation and activation (Witthuhn et al., 1993; Miura et al., 1994b). Phosphorylation of Jak2, in turn, phosphorylates several tyrosine residues on EPOR providing docking sites for binding of several intracellular proteins and activation of multiple signaling cascades.

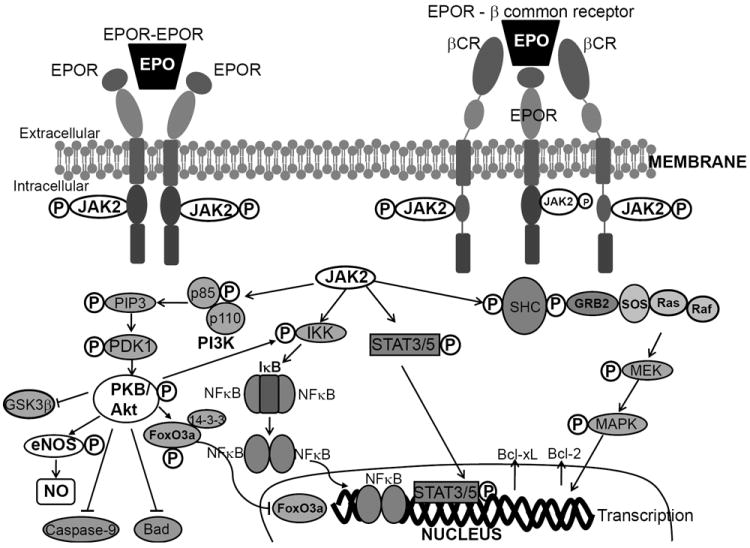

The tissue protective effects of EPO, beyond the hematopoietic system, is mediated but not restricted to activation of homodimeric EPOR, but is also believed to be mediated by its actions on the heterotrimeric complex consisting of EPOR and the β-common receptor (βCR, also known as CD131). The β-common receptor is a shared receptor subunit of interleukin 3, interleukin 5 and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (Brines et al., 2004; Brines and Cerami, 2005). This heterotrimeric complex is postulated to mediate EPO-induced cytoprotection in the nervous system, while the involvement of EPOR-βCR complex in EPO-mediated protection in the cardiovascular system has not yet been demonstrated. Nevertheless, following binding of EPO to either homodimeric or heterotrimeric receptor complex activates Jak2. Signal transduction pathways mediating tissue protection in the cardiovascular system activated by EPO-induced phosphorylation by Jak2 are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Signaling pathways mediating EPO-induced protection in the cardiovascular system.

Binding of EPO to either the homodimeric EPO-receptor (EPOR) complex or the heterotrimeric EPOR-βCR complex first activates Janus tyrosine kinase 2 (Jak2). Phosphorylation and activation of Jak2 recruits secondary messengers and activates secondary signaling pathways including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and nuclear factor-κB. Some of the pathways mediating EPO-mediated protection are similar to those mediating erythropoiesis or neuroprotection. In particular, EPO-mediated inhibition of apoptosis involves activation of protein kinase B/Akt to inhibit caspase-9 or activate nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) or inhibit Bad, or stimulate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), or MAPK pathway to increase anti-apoptotic messengers in the mitochondria including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. The most common pathway for EPO-mediated cardioprotection as well as vascular protection is EPO-induced augmentation of nitric oxide (NO) production by PI3K/Akt phosphorylation and activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). EPO is also shown to regulate intracellular Ca2+ by activating phospholipase C (PLC).

Stimulation with EPO, on one hand, activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling by recruiting its p85 regulatory subunit to EPOR (Miura et al., 1994a). Phosphorylation and activation of PI3K is coupled to activation of protein kinase B/Akt, a pathway known to stimulate anti-apoptotic signals that facilitate the inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c release, in part by translocating pro-apoptotic Bad to mitochondria, and help maintain mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 1). EPO-induced Akt activation prevents nuclear translocation of the pro-apoptotic forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a by facilitating its binding with the protein 14-3-3 (Chong and Maiese, 2007). In addition, EPO stimulation in the myocardium may lead to phosphorylation and inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) in either an Akt-dependent or an independent mechanism (Nishihara et al., 2006; Miki et al., 2009). In peripheral and cerebral vasculature, activation of Akt by EPO phosphorylates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and increases nitric oxide (NO) production (Santhanam et al., 2005; Santhanam et al., 2006; d’Uscio et al., 2007). Akt activation may also prevent activation of caspase-9 to prevent apoptosis in the cerebral vasculature (Chong et al., 2003).

Phosphorylation of Jak2 may directly activate inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase (IκB kinase or IKK), or indirectly activate Akt to stimulate nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) for nuclear transcription (Figure 1) and exerts cardioprotection (Xu et al., 2005). In isolated perfused rabbit hearts, EPO has been shown to protect the heart against ischemia by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT-5) and/or mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Rafiee et al., 2005).

IV. Mechanisms of Vascular Protective Effects of Erythropoietin

A. Erythropoietin and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase

NO is a potent vasodilator and plays a key role in control of the cardiovascular system (Lüscher and Vanhoutte, 1990). NO is formed in endothelial cells from L-arginine by oxidation of its terminal guanidino-nitrogen, requiring the cofactors (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase, flavin adenine dinucleotide, heme, and Zn2+ (Palmer et al., 1987; Palmer et al., 1988; Ignarro, 1990; Raman et al., 1998). The formation of NO occurs by activation of eNOS, which is expressed constitutively (Förstermann et al., 1991; Pollock et al., 1991). Relaxations in response to the abluminal release of endothelium-derived NO are associated with stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase and in turn formation of cyclic guanosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cGMP) in vascular smooth muscle cells (Rapoport et al., 1983).

Accumulating experimental evidence suggests that EPO can exert non-erythropoietic effects in vascular endothelium and is increasingly regarded as a potent tissue protective cytokine. Indeed, EPO decreases tissue damage by inhibition of apoptosis and reduction of inflammatory cytokines (Iversen et al., 1999; Rui et al., 2005; Burger et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006). Indeed, in-vitro treatment with low dose of rhEPO increased eNOS protein expression and NO2-/NO3- levels in cultured endothelial cells (Table 2) (Wu et al., 1999; Banerjee et al., 2000; Beleslin-Cokic et al., 2004). However, incubation of human coronary artery endothelial cells with high dose of rhEPO for 24 hours inhibited eNOS expression and NO production (Wang and Vaziri, 1999). Moreover, asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations were increased after high dose of rhEPO or NESP over longer period leading to a significant reduction of NO synthesis in cultured endothelial cells (Table 2) suggesting that high dose of EPO may have detrimental effects on endothelial function (Scalera et al., 2005).

Table 2.

In vitro effects of recombinant human EPO on eNOS expression in cultured endothelial cells.

| Cell type | Dose of rhEPO | Treatment duration | Reguation | Method of detection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | 0.1, 1, 20, and 40 U/mL | 8 hours | Up-regulation | NO2-/NO3- bioassay | (Wu et al., 1999) |

| Human umbilical vein, dermis, and pulmonary artery endothelial cells | 4 U/mL | 1-6 days | Up-regulation | RT-PCR, L-arginine-to-L-citrulline conversion assay | (Banerjee et al., 2000) |

| Human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells | 5 U/mL | 1 hour | Up-regulation | Western blot, NO3- bioassay | (Beleslin-Cokic et al., 2004) |

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | 5 U/mL | 0.5 hour | Up-regulation | NO3- bioassay | (Beleslin-Cokic et al., 2004) |

| Bovine aortic endothelial cells | 0.1 - 10 U/mL | 1-24 hours | No change | Western blot | (Lopez Ongil et al., 1996) |

| Human artery endothelial cells | 5 U/mL | 1 hour | No change | Western blot, NO3- bioassay | (Beleslin-Cokic et al., 2004) |

| Human coronary artery endothelial cells | 5 and 20 U/mL | 24 hours | Down-regulation | Western blot, NO2-/NO3- bioassay | (Wang and Vaziri, 1999) |

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | 10, 50, 100, and 200 U/mL | 24 hours | Down-regulation | NO2-/NO3- bioassay | (Scalera et al., 2005) |

rhEPO, recombinant human erythropoietin; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO2-, nitrite; NO3-, nitrate.

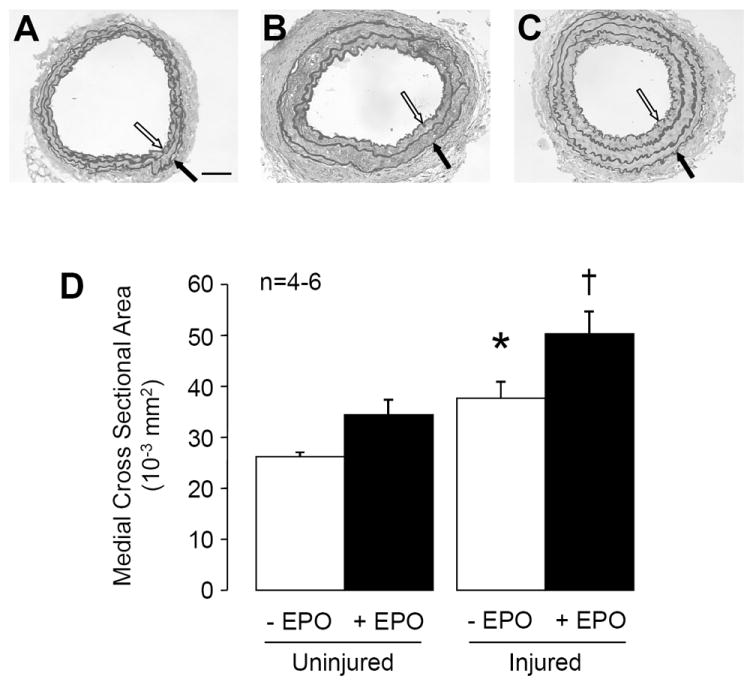

As illustrated in Table 3, in-vivo treatment with rhEPO has been shown to increase urinary NO2-/NO3- levels in normotensive rats (del Castillo et al., 1995; Tsukahara et al., 1997), increase vascular eNOS phosphorylation and eNOS protein expressions (Ruschitzka et al., 2000; Kanagy et al., 2003; d’Uscio et al., 2007), improve endothelium-dependent relaxations in isolated aortas of rats and mice (Tsukahara et al., 1997; Iversen et al., 1999; Ruschitzka et al., 2000; Kanagy et al., 2003), and improve endothelial function in predialysis patients (Kuriyama et al., 1996). Furthermore, in transgenic mice overexpression of human EPO markedly increased aortic eNOS protein expression, NO-mediated endothelium dependent relaxation, and circulating and vascular tissue NO levels (Table 3). These mice do not develop hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, or thromboembolic complications despite excessive erythrocytosis exhibiting very high hematocrit levels of 80% (Ruschitzka et al., 2000). The increased NO production in these animals appears to counteract increased expression of potent vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Quaschning et al., 2003). Indeed, EPO transgenic mice treated with the NO synthase inhibitor exhibit high systolic blood pressure and show increased mortality whereas wild-type siblings develop only hypertension (Ruschitzka et al., 2000). Despite concomitant activation of the ET-1 system observed in transgenic mice, elevated NO levels led to a pronounced vasodilation, thereby protecting the transgenic animals from cardiovascular complications. Consistent with this concept, studies on cultured endothelial cells demonstrated that inactivation of NO synthesis caused increased production of ET-1 (Boulanger and Lüscher, 1990). In addition, EPO increased systolic blood pressure, accelerated thrombus formation, and exacerbated medial thickening of injured carotid arteries in eNOS-deficient mice (d’Uscio et al., 2007; Lindenblatt et al., 2007). These observations underscore the importance of eNOS during vascular adaptation to increased circulating levels of EPO.

Table 3.

In vivo effects of recombinant human EPO on vascular eNOS in animal studies.

| Animal species | Dose of rhEPO | Treatment duration | Cell tissue | Result | Method of detection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nephrectomized Sprague-Dawley rat | 150 U/kg, intraperitoneal, twice a week | 6 weeks | Thoracic aorta | No change | Western blot, NOx bioassay | (Ni et al., 1998) |

| Rabbit | 400 U/kg, intravenous, each other day | 1 week | Carotid artery | No change | Endothelium-dependent vasodilation studies in isolated artery | (Noguchi et al., 2001) |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | 100 U/kg or 300 U/kg, subcutaneous, each other day | 2 weeks | Urine | Up-regulation | NOx bioassay | (Tsukahara et al., 1997) |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | 150 U/kg, subcutaneous, three times per week | 3 weeks | Urine | Up-regulation | NOx bioassay | (del Castillo et al., 1995) |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | ~ 160 U/kg/day, subcutaneous | 2 weeks | Thoracic aorta | Up-regulation | Western blot, NOx bioassay, endothelium-dependent vasodilation studies in isolated aorta | (Kanagy et al., 2003) |

| EPO-transgenic mice | n/a | n/a | Aorta | Up-regulation | Western blot, NOx bioassay, endothelium-dependent vasodilation studies in isolated aorta | (Ruschitzka et al., 2000) |

| C57BL/6 mice | 1000 U/kg, subcutaneous, twice a week | 2 weeks | Aorta | Up-regulation | Western blot | (d’Uscio et al., 2007) |

| C57BL/6 mice | 1000 U/kg, intraperitoneal, for the initial 3 days | 2 weeks | Endothelial progenitor cells | Up-regulation | Immunohistochemistry, NOx bioassay | (Urao et al., 2006) |

Because of an increased number of circulating red blood cells by EPO, subsequent increase in shear stress is a powerful stimulus for up-regulation of eNOS in endothelial cells (Berk et al., 1995; Ruschitzka et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2001; Boo et al., 2002; Lam et al., 2006). However, administration of EPO for 3 days, although not affecting the number of circulating red blood cells, stimulated phosphorylation of eNOS to a similar degree as did treatment with EPO for 14 days. These findings suggest that EPO has a direct stimulatory effect on phosphorylation of eNOS in vascular endothelium and that this effect is independent of hematopoietic effects of EPO (d’Uscio et al., 2007). Most recently, it was demonstrated that activation of eNOS by hypoxia was abolished in EPO-receptor-deficient mice, the latter mutants also exhibiting an exacerbation of pulmonary hypertension and vascular injury. These findings suggest that the vascular protective effects of EPO are dependent on NO production via activation of the EPO receptor in endothelial cells (Beleslin-Cokic et al., 2004; Satoh et al., 2006).

B. Erythropoietin and protein kinase B/Akt

As discussed earlier, EPO elicits phosphorylation of Akt and this is dependent upon the activation of Jak2 and PI3K. Numerous studies demonstrated tissue protective effects of both rhEPO and darbepoetin alpha mediated by phosphorylation of Akt and a subsequent increase in the production of NO (Chong et al., 2002; Bahlmann et al., 2004b; Santhanam et al., 2006; Chong and Maiese, 2007; Lindenblatt et al., 2007; d’Uscio and Katusic, 2008). To date, the cardiovascular effects of third generation of EPO analogues are largely unknown.

C. Erythropoietin and Tetrahydrobiopterin

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is an essential cofactor required for enzymatic activity of eNOS (Raman et al., 1998). The biosynthesis of BH4 is dependent on activity of the rate-limiting enzyme GTP-cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH I) (Nichol et al., 1985). Recent study showed that EPO causes an increase in intracellular levels of BH4 via activation of GTPCH I (d’Uscio and Katusic, 2008). Pharmacological inhibition of Jak2 with AG490 abolished EPO-induced BH4 biosynthesis, suggesting that increased phosphorylation and activation of Jak2 are the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed effect of EPO on BH4 synthesis. Further analysis revealed that PI3K activity is an upstream activator of Akt1, because pharmacological and genetic inactivation of PI3K/Akt1 abolishes the stimulatory effects of EPO on GTPCH I activity and biosynthesis of BH4 in mouse aorta (d’Uscio and Katusic, 2008). The ability of EPO to upregulate GTPCH I activity and eNOS phosphorylation in a coordinated fashion is most likely designed to optimize the production of NO in vascular endothelium.

D. Erythropoietin and Antioxidant Enzymes

The local concentrations of NO in arterial wall are not only dependent on enzymatic activity of eNOS but are also determined by concentrations of superoxide anions (Harrison, 1994). Indeed, recent study showed that in wild-type mice, treatment with EPO increases vascular CuZn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) expression and effectively prevents vascular remodeling after carotid artery injury (d’Uscio et al., 2010). In contrast, genetic inactivation of SOD1 abolished ability of EPO to reduce concentrations of superoxide anions thereby suggesting that EPO exerts antioxidant effect in blood vessel wall by regulating expression and activity of SOD1 protein.

E. Adverse Effects of Erythropoietin

Normally, endothelial cells contribute to the regulation of blood pressure and blood flow by releasing vasodilators such as NO and prostacyclin, as well as vasoconstrictors including ET-1 and prostanoids (Lüscher and Vanhoutte, 1990). Long-term administration of rhEPO has been associated with hypertension (Krapf and Hulter, 2009). The mechanisms of hypertension induced by long-term administration of EPO include increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations and increased ET-1 production leading to a blunted response to the vasodilator NO in rabbits and rats (Bode-Boger et al., 1992; Vaziri et al., 1995). Chronic use of EPO raises cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells or platelets (Van Geet et al., 1990; Neusser et al., 1993; Vaziri et al., 1996) and in turn, may contribute to impaired responses to NO donors. It is also suggested that EPO, at doses exceeding 200 U/mL, activates tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ, which hydrolyzes phosphatidyinositol bisphosphate to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol. These second messengers may, in turn, elevate Ca2+ concentration as well as activate protein kinase C in vascular smooth muscle cells (Akimoto et al., 1999; Akimoto et al., 2001). Similar doses of EPO (200 U/mL) released ET-1 and increased constrictor prostanoids over dilator prostanoids in vitro in endothelial cells (Bode-Boger et al., 1996; Krapf and Hulter, 2009) and these observations may help to explain EPO-induced hypertension observed in animals and in humans.One implication of these results is that endothelial dysfunction predisposes to EPO dependent hypertension. In a recent study, EPO treatment caused hypertension in rats treated in combination with a NOS inhibitor but not in rats treated with EPO alone (Moreau et al., 2000). In addition, a study using polycythemic mice overexpressing rhEPO observed that NOS blockade caused the normotensive polycythemic mice to develop hypertension (Ruschitzka et al., 2000). Therefore, erythropoiesis with a raised hematocrit is not likely associated with an increased risk for hypertension and thrombosis as long as endothelial NO production serves as compensatory mechanism (Moreau et al., 2000; d’Uscio et al., 2007; Lindenblatt et al., 2007; d’Uscio and Katusic, 2008). Impaired endothelial-dependent dilation in hypertensives (Spieker et al., 2000) as well as in hemodialyzed patients (Joannides et al., 1997) and the impaired ability to synthesize endothelial NO may increase susceptibility to EPO-induced hypertension.

V. Erythropoietin and Cardioprotection

Endogenous EPO system facilitates cardiomyocyte survival after ischemia-reperfusion injury and accelerates left ventricular remodeling (Tada et al., 2006). Deficiency of endogenous EPO-EPOR system resulted in acceleration of pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by accelerating left ventricular hypertrophy, dysfunction and reduced survival (Asaumi et al., 2007). Therapeutic potential of EPO to exert cardioprotection was demonstrated in models of myocardial ischemia wherein EPO inhibited apoptosis and augmented survival of cardiac myocytes (Calvillo et al., 2003; Parsa et al., 2003), mediated in part, by activating EPOR expressed on the cardiac myocytes (Wright et al., 2004). Favorable results from numerous studies offered promise for administering EPO to treat myocardial infarction (Cai et al., 2003; Calvillo et al., 2003; Moon et al., 2003; Parsa et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2004).

However, subsequent studies in-vitro identified activation of multiple signaling pathways in EPO-induced cardioprotection (Shi et al., 2004; Rafiee et al., 2005). In particular, EPO-mediated cardioprotection involves activation of one or more of the following pathways: Jak/STAT pathway, Jak2/PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway, Jak2/MAPK pathway as well as activation of protein kinase Cε. Cardioprotection by EPO also seems to be mediated by activation of potassium channels, in particular, KATP and mitochondrial calcium-activated potassium channels (Shi et al., 2004). Administration of EPO before ischemia, at the onset of ischemia or after reperfusion triggered response mimicking preconditioning in the ischemic myocardium (Parsa et al., 2003; Baker, 2005; Gross and Gross, 2006). However, the role of EPOR in this supposed pre-conditioning response remains to be clarified. In addition, the ability of EPO to stimulate eNOS activation may also facilitate cardiomyocyte survival, as observed during hypoxia-induced apoptosis of cardiac myocytes (Burger et al., 2006). As mentioned earlier, the doses of EPO for cardioprotection far-exceeded the doses of EPO used in treatment of anemia and clinical translations of these results may be hampered by the onset of widely-reported adverse events. In this regard, understanding of the role of EPOR-βCR receptor complex may help expand clinical applications of non-hematopoietic analogues of EPO to cardioprotection. Recent success with carbamylated EPO, which selectively binds to EPOR-βCR heteromer, in a mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion injury (Xu et al., 2009) provides a promising outlook toward expanding tissue protection of EPO in the clinic to cardioprotection.

Occurrence of anemia as a risk factor for morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure necessitated evaluation of EPO in clinical trials. Randomized, single-center studies successfully demonstrated treatment of anemia in patients with mild, moderate or severe heart failure with associated improvement in exercise capacity, cardiac and renal function and reduced use of diuretics (Silverberg et al., 2001; Mancini et al., 2003; Namiuchi et al., 2005; Palazzuoli et al., 2006). Recently, three trials evaluated the safety and efficacy of darbepoetin alfa (0.75 μg/kg once every 2 weeks) in symptomatic heart failure patients (Ponikowski et al., 2007; van Veldhuisen et al., 2007; Ghali et al., 2008). Incidence of adverse events in these trials was similar between placebo- and darbepoetin alfa-treated patients (Klapholz et al., 2009), while an increase in hemoglobin with darbepoetin alfa treatment tended to correlate with improved health-related quality of life. Results obtained in these clinical trials extend support as a proof of concept and encourage the need for larger outcomes trials for treatment of anemia with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.

In addition to treatment of anemia, results from pre-clinical studies attribute multiple mechanisms of protection by EPO against myocardial disorders. Treatment with EPO may decrease apoptosis of myocytes, induce neovascularization by promoting myocardial angiogenesis, reduce collagen deposition in ischemic myocardium as well as improve left ventricular function. Employing either non-hematopoietic analogues of EPO or a novel EPO delivery system (Kobayashi et al., 2008) may expand therapeutic boundary for EPO-mediated cardioprotection. Success from these studies will lay the frame work for future clinical evaluation in the treatment of myocardial infarction.

VI. Erythropoietin and Cerebrovascular Disorders

Identification of EPO and EPOR in the brain (Tan et al., 1992; Masuda et al., 1994) expanded investigations into tissue protective effects of EPO, beyond the hematopoietic system. Initial research ascribed EPO-mediated protection to the cytokine’s ability to inhibit apoptosis in tissues adjacent to a pathological insult in the brain. The current understanding of the tissue protective effects of EPO in the nervous system involves interaction of the non-hematopoietic βCR with the classical EPOR and subsequent activation of multiple signaling cascades, as reviewed by Brines and Cerami (Brines and Cerami, 2005). In the nervous system, EPO mediates neuroprotection following ischemic, hypoxic, metabolic, neurotoxic and excitotoxic stress (Genc et al., 2004). EPO-mediated protective effects in the brain may involve one or more of the following mechanism: a) prevention of excitatory aminoacid release, b) inhibition of apoptosis, c) anti-oxidant effects, d) anti-inflammatory effects and e) stimulation of neurogenesis and angiogenesis.

EPO exhibits higher affinity for endothelium of cerebral arteries as compared to neuronal cells (Brines and Cerami, 2006). Prior studies have demonstrated that EPO activates cerebrovascular protective mechanisms (Grasso et al., 2002; Grasso, 2004; Santhanam et al., 2005; Santhanam et al., 2006). In cerebral arteries exposed to recombinant EPO, the expressions of eNOS and its phosphorylated (S1177) form were increased. Basal levels of cGMP were also significantly elevated consistent with increased NO production. Over-expression of EPO in cerebral arteries reversed vasospasm in rabbits induced by injection of autologous blood into cisterna magna. Arteries-transduced with recombinant EPO demonstrated significant augmentation of the endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine. Over-expression of EPO further increased the expression of phosphorylated Akt and eNOS and elevated basal levels of cGMP in the spastic arteries (Santhanam et al., 2005). Cerebrovascular protective effects of EPO against cerebral vasospasm following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage may appear to be mediated in part by phosphorylation and activation of endothelial Akt/eNOS pathway.

Administration of EPO into the brain reduced neurologic dysfunction in rodent models of stroke (Sadamoto et al., 1998; Sakanaka et al., 1998; Bernaudin et al., 1999; Brines et al., 2000; Siren et al., 2001). Following the success of EPO in pre-clinical models of stroke and cerebral ischemia, a successful proof of concept clinical trial demonstrated that intravenously injected EPO was well tolerated in patients with acute ischemic stroke (Ehrenreich et al., 2002). In addition, outcomes from a recent Phase II trial reports beneficial effect of EPO, as observed from a reduction in delayed ischemic deficits after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (Tseng et al., 2009).

However, results from the German Multicenter EPO Stroke Phase II/III trial warrants caution in administering EPO with thrombolytics in patients with acute stroke (Ehrenreich et al., 2009). In this trial, patients receiving EPO alone demonstrated a reduction in National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score from day 1 to day 90, an index of improved neurological outcome. On the contrary, when combined with thrombolytic recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, patients receiving EPO demonstrated increased risk of complications including death, intracerebral hemorrhage, brain edema, and thromboembolic events compared to patients receiving placebo. Further understanding of the complex interactions between different components of the cardiovascular system initiated by EPO is necessary for designing better strategies to maximize therapeutic potential of this cytokine.

With new evidences pointing toward the role of non-hematopoietic βCR in EPO-mediated tissue protective effects (Grasso et al., 2004), use of non-erythrocytic analogues of EPO currently under development offer promise of therapy as adjunct for patients with stroke and other cerebral vascular disorders with enhanced safety and reduced adverse effects. Another novel strategy currently investigated for acute stroke has employed the neurotrophic ability of EPO to differentiate neural progenitor cells into neurons. The Phase IIb prospective randomized, double-blind study of NTx™-265, comprising human chorionic gonadotrophin (for proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells) and EPO (to differentiate these neural stem cells) aims to improve neurological outcome in acute stroke patients, and was based on the success of pre-clinical studies adopting similar strategy in rats (Belayev et al., 2009).

VII. Erythropoietin and Progenitor Cells

Seminal studies by Heeschen et al. (Heeschen et al., 2003) demonstrated that circulating levels of EPO in humans significantly correlated with the number of stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow as well as to the number and function of circulating progenitor cells. In addition, treatment of mice with EPO increased the number of stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow as well as an increase in the number of peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), suggestive of stimulation of mobilization by EPO. Indeed, mobilization of progenitor cells by EPO stimulated postnatal neovascularization in a model of hind limb ischemia (Heeschen et al., 2003; Li et al., 2009; Kato et al., 2010). Numerous studies, subsequently, have established a crucial pro-angiogenic role of EPO, as indicated by enhanced mobilization of progenitor cells, to elicit vascular repair. As illustrated in Table 4, treatment with EPO significantly augments mobilization of diverse population of progenitor cells from bone marrow distinguished by their distinct phenotype and, in turn, the mobilized progenitor cells contributed to either neovascularization or repair of denuded endothelium.

Table 4.

Contribution to vascular repair by progenitor cells mobilized by EPO.

| Species | Dose of EPO | Functional Outcome | Phenotype of mobilized progenitor cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice, Humans | 1000 U/kg | Increased angiogenesis in models of disc neovascularization and hind limb ischemia | Lin-1+/Sca-1+ stem cells | (Heeschen et al., 2003) |

| Sca-1+/Flk-1+ or CD34+/Flk-1+ cells | ||||

| Humans | 5000 ± 674 U | Increased angiogenesis in EPCs of patients exposed to EPO | CD34+/CD45+ cells | (Bahlmann et al., 2004a) |

| UEA-1+/acLDL-DiI+ cells | ||||

| Mice | 1000 U/kg | Inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia after wire injury of femoral artery | CD45dim/Flk-1+ cells | (Urao et al., 2006) |

| Sca-1+/Flk-1+ cells | ||||

| Mice | 100 U | Accelerated revascularization in a model of hind limb ischemia | CXCR4+/VEGFR1+-hemangiocytes | (Jin et al., 2006) |

| Dogs | 1000 U/kg | Augmented neovascularization in a model of myocardial infarction | CD34+-mononuclear cells | (Hirata et al., 2006) |

| Di-acLDL+/UEA-I cells | ||||

| Rats | 40 μg/kg | Increased functional neovascularization following acute myocardial infarction | Ac-LDL+/Lectin+ cells per high powered field | (Westenbrink et al., 2007) |

| Mice | 1000 U/kg | Epo-induced mobilization impaired in eNOS-/- mice | Lin-1-/Sca-1+/c-Kit+ cells | (Santhanam et al., 2008) |

| CD34+/Flk-1+ cells | ||||

| Mice | 500 U/Kkg | Acceleration of smooth muscle lesion formation by EPO in a model of carotid artery ligation | Ter-119-/CD45lo/c-Kit+/Sca-1+ cells | (Janmaat et al.) |

This table summarizes the results from studies wherein EPO was administered to stimulate mobilization of progenitor cells in a model of vascular injury. Studies relating increased endogenous levels of EPO with enhanced mobilization of progenitor cells and their contribution to vascular repair have not been discussed.

Multiple mechanisms are likely to mediate mobilization of progenitor cells by EPO (Heeschen et al., 2003; Aicher et al., 2005; Urao et al., 2006). Prior studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is critical for EPO-induced mobilization of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and CD34+/Flk-1+ EPCs (Santhanam et al., 2008). The ability of EPO to up-regulate the antioxidant capacity of EPCs, in particular, activation of SOD1 may also help to explain the pronounced vascular protection observed with this pleiotropic cytokine (He et al., 2005).

Endogenous EPO/EPOR system in the vasculature also dictates mobilization of progenitor cells and facilitates vascular repair. Satoh et al. (Satoh et al., 2006) successfully demonstrated this crucial role of endogenous EPO/EPOR using EPOR null mutant mice that expresses EPO-R exclusively in the erythroid lineage (EPOR-/- rescued mice). Lack of EPOR signaling in the hematopoietic system resulted in attenuated mobilization of Flk-1+/CD133+ EPCs (hematopoietic progenitor cell population) (Satoh et al., 2006), as well as alteration in VEGF/VEGFR signaling and impaired recovery after hind limb ischemia in mice (Nakano et al., 2007). During hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension, in addition to impaired endogenous mobilization, recruitment of administered progenitor cells was impaired in EPOR-/- rescued mice (Satoh et al., 2006). It is likely that endogenous EPO-mediated effects are not restricted to its effects on mature vascular cells, but also contributes to mobilization, recruitment and activation of progenitor cells as demonstrated in either hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (Satoh et al., 2006) or in a model of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion (Tada et al., 2006). Elevated plasma levels of EPO in patients with acute myocardial infarction correlated with mobilization of CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2+ EPCs (Ferrario et al., 2007). It is therefore likely that the extent of alteration of endogenous EPO levels following a cardiovascular insult may dictate the proportion of endogenous progenitor cells mobilized in the mononuclear cell population, which in turn, may contribute to extent of damage or repair.

VIII. Conclusions

Extensive research has demonstrated that EPO does not only affect the hematopoietic system, but also plays important role in control of cardiovascular system. EPO has been shown to be vascular protective by exerting its effects on the endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. Tissue protective effects of EPO on the vasculature are mediated, in part, by prevention of apoptosis or stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide production and augmented vasodilatation. In addition, EPO regulates mobilization of pro-angiogenic cells, including EPCs, from the bone marrow and stimulates neovascularization. EPO may exert its beneficial effects on the vasculature by acting through its homodimeric EPOR or through EPOR-βCR and activation of Jak2 to stimulate PI3K/Akt, NFκB, MAPK signaling pathways. Further studies are however needed to clarify the receptor(s) involved in protective effects of EPO in different vascular cell types and injury models. In addition, exacerbation of injury in EPO-treated mice deficient in either eNOS or CuZn superoxide dismutase highlights the critical role of endogenous NO or antioxidant defense mechanisms in triggering adaptation of vascular wall to elevated doses of EPO, commonly used in preclinical and clinical settings. These studies may help to explain the adverse events precluding the clinical use of EPO in treatment of cardiovascular and neurological disorders.

Results obtained from clinical trials with EPO on cerebrovascular disorders, conducted over the last decade, suggests EPO as a promising lead towards designing and developing novel strategies for these disorders. Future research on better understanding of protective effects of the non-hematopoietic analogues of EPO as well as harnessing the EPO-induced ability to stimulate progenitor cell function may favor therapeutic benefits with minimal side effects associated with this pleiotropic cytokine.

Figure 2. Morphological studies of carotid arteries of eNOS-deficient mice undertaken fourteen days after injury.

Carotid arteries were stained with standard Verhoeff van-Giessen. Representative photomicrographs of uninjured carotid arteries (A), carotid arteries after injury (B), and injured carotid arteries of eNOS-deficient mice treated with EPO for 14 days (C). The media is demarcated by internal elastic lamina (open arrow) and external elastic lamina (black arrow). Original magnification x200. Size bar = 50 μm. D: Quantitative histomorphometric analyses of medial CSA in carotid arteries of eNOS-deficient mice without (-) and with (+) EPO treatment. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n=4-6). * P<0.05 vs. control uninjured; † P<0.05 vs. uninjured + EPO (ANOVA with Bonferroni’s).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL53524, HL91867 (to ZSK), Roche Foundation for Anemia Research, American Heart Association Scientist Development Grants #07301333N (to LVD), #0835436N (to AVRS), and the Mayo Foundation.

Abbreviations

- EPO

erythropoietin

- EPOR

erythropoietin-receptor

- βCR

β-common receptor

- rhEPO

recombinant human erythropoietin

- NESP

novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein

- CERA

continuous erythropoietin receptor activator

- Jak2

Janus kinase 2

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa B

- STAT-5

signal transducer and activator of transcription 5

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine 3’,5’-monophosphate

- ET-1

endothelin-1

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Aicher A, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Mobilizing endothelial progenitor cells. Hypertension. 2005;45:321–325. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154789.28695.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto T, Kusano E, Ito C, Yanagiba S, Inoue M, Amemiya M, Ando Y, Asano Y. Involvement of erythropoietin-induced cytosolic free calcium mobilization in activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and DNA synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens. 2001;19:193–202. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto T, Kusano E, Muto S, Fujita N, Okada K, Saito T, Komatsu N, Ono S, Ebata S, Ando Y, Homma S, Asano Y. The effect of erythropoietin on interleukin-1beta mediated increase in nitric oxide synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1249–1256. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammarguellat F, Gogusev J, Drueke TB. Direct effect of erythropoietin on rat vascular smooth-muscle cell via a putative erythropoietin receptor. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:687–692. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou A, Liu Z, Steiner M, Chin K, Lee ES, Kessimian N, Noguchi CT. Erythropoietin receptor mRNA expression in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3974–3978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaumi Y, Kagaya Y, Takeda M, Yamaguchi N, Tada H, Ito K, Ohta J, Shiroto T, Shirato K, Minegishi N, Shimokawa H. Protective role of endogenous erythropoietin system in nonhematopoietic cells against pressure overload-induced left ventricular dysfunction in mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2022–2032. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlmann FH, De Groot K, Spandau JM, Landry AL, Hertel B, Duckert T, Boehm SM, Menne J, Haller H, Fliser D. Erythropoietin regulates endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2004a;103:921–926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlmann FH, Song R, Boehm SM, Mengel M, von Wasielewski R, Lindschau C, Kirsch T, de Groot K, Laudeley R, Niemczyk E, Guler F, Menne J, Haller H, Fliser D. Low-dose therapy with the long-acting erythropoietin analogue darbewpoetin alpha persistently activates endothelial Akt and attenuates progressive organ failure. Circulation. 2004b;110:1006–1012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139335.04152.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JE. Erythropoietin mimics ischemic preconditioning. Vascul Pharmacol. 2005;42:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Rodriguez M, Nag M, Adamson JW. Exposure of endothelial cells to recombinant human erythropoietin induces nitric oxide synthase activity. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1895–1904. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayev L, Khoutorova L, Zhao KL, Davidoff AW, Moore AF, Cramer SC. A novel neurotrophic therapeutic strategy for experimental stroke. Brain Res. 2009;1280:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beleslin-Cokic BB, Cokic VP, Yu X, Weksler BB, Schechter AN, Noguchi CT. Erythropoietin and hypoxia stimulate erythropoietin receptor and nitric oxide production by endothelial cells. Blood. 2004;104:2073–2080. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk BC, Corson MA, Peterson TE, Tseng H. Protein kinases as mediators of fluid shear stress stimulated signal transduction in endothelial cells: a hypothesis for calcium-dependent and calcium-independent events activated by flow. J Biomech. 1995;28:1439–1450. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaudin M, Marti HH, Roussel S, Divoux D, Nouvelot A, MacKenzie ET, Petit E. A potential role for erythropoietin in focal permanent cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:643–651. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleuel H, Hoffmann R, Kaufmann B, Neubert P, Ochlich PP, Schaumann W. Kinetics of subcutaneous versus intravenous epoetin-beta in dogs, rats and mice. Pharmacology. 1996;52:329–338. doi: 10.1159/000139398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode-Boger SM, Boger RH, Kuhn M, Radermacher J, Frolich JC. Endothelin release and shift in prostaglandin balance are involved in the modulation of vascular tone by recombinant erythropoietin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20(Suppl 12):S25–28. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode-Boger SM, Boger RH, Kuhn M, Radermacher J, Frolich JC. Recombinant human erythropoietin enhances vasoconstrictor tone via endothelin-1 and constrictor prostanoids. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1255–1261. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsdorff E, Jalavisto E. A humoral mechanism in anoxic erythrocytosis. Acta Physiol Scand. 1948;16:150–170. [Google Scholar]

- Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Du J, Jo H. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger C, Lüscher TF. Release of endothelin from the porcine aorta: Inhibition by endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:587–590. doi: 10.1172/JCI114477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. Emerging biological roles for erythropoietin in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. Discovering erythropoietin’s extra-hematopoietic functions: biology and clinical promise. Kidney Int. 2006;70:246–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Grasso G, Fiordaliso F, Sfacteria A, Ghezzi P, Fratelli M, Latini R, Xie QW, Smart J, Su-Rick CJ, Pobre E, Diaz D, Gomez D, Hand C, Coleman T, Cerami A. Erythropoietin mediates tissue protection through an erythropoietin and common beta-subunit heteroreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14907–14912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406491101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines ML, Ghezzi P, Keenan S, Agnello D, de Lanerolle NC, Cerami C, Itri LM, Cerami A. Erythropoietin crosses the blood-brain barrier to protect against experimental brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10526–10531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger D, Lei M, Geoghegan-Morphet N, Lu X, Xenocostas A, Feng Q. Erythropoietin protects cardiomyocytes from apoptosis via up-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Manalo DJ, Wei G, Rodriguez ER, Fox-Talbot K, Lu H, Zweier JL, Semenza GL. Hearts from rodents exposed to intermittent hypoxia or erythropoietin are protected against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2003;108:79–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078635.89229.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo L, Latini R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P, Ghezzi P, Salio M, Cerami A, Brines M. Recombinant human erythropoietin protects the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury and promotes beneficial remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4802–4806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630444100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Erythropoietin is a novel vascular protectant through activation of Akt1 and mitochondrial modulation of cysteine proteases. Circulation. 2002;106:2973–2979. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039103.58920.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Apaf-1, Bcl-xL, cytochrome c, and caspase-9 form the critical elements for cerebral vascular protection by erythropoietin. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:320–330. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000050061.57184.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Erythropoietin involves the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, 14-3-3 protein and FOXO3a nuclear trafficking to preserve endothelial cell integrity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:839–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Uscio LV, Katusic ZS. Erythropoietin increases endothelial biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin by activation of protein kinase B alpha/Akt1. Hypertension. 2008;52:93–99. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Uscio LV, Smith LA, Katusic ZS. Erythropoietin increases expression and function of vascular copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase. Hypertension. 2010;55:998–1004. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Uscio LV, Smith LA, Santhanam AV, Richardson D, Nath KA, Katusic ZS. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular effects of erythropoietin. Hypertension. 2007;49:1142–1148. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.085704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ME, Cai H, Drummond GR, Harrison DG. Shear stress regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression through c-Src by divergent signaling pathways. Circ Res. 2001;89:1073–1080. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo D, Raij L, Shultz PJ, Tolins JP. The pressor effect of recombinant human erythropoietin is not due to decreased activity of the endogenous nitric oxide system. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:505–508. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egrie JC, Browne JK. Development and characterization of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP) Br J Cancer. 2001;84(Suppl 1):3–10. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egrie JC, Dwyer E, Browne JK, Hitz A, Lykos MA. Darbepoetin alfa has a longer circulating half-life and greater in vivo potency than recombinant human erythropoietin. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:290–299. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egrie JC, Grant JR, Gillies DK, Aoki KH, Strickland TW. The role of carbohydrate on the biological activity of erythropoietin. Glycoconjugate J. 1993;10:263. [Google Scholar]

- Egrie JC, Strickland TW, Lane J, Aoki K, Cohen AM, Smalling R, Trail G, Lin FK, Browne JK, Hines DK. Characterization and biological effects of recombinant human erythropoietin. Immunobiology. 1986;172:213–224. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(86)80101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Dembowski C, Cepek L, Lewczuk P, Stiefel M, Rustenbeck HH, Breiter N, Jacob S, Knerlich F, Bohn M, Poser W, Ruther E, Kochen M, Gefeller O, Gleiter C, Wessel TC, De Ryck M, Itri L, Prange H, Cerami A, Brines M, Siren AL. Erythropoietin therapy for acute stroke is both safe and beneficial. Mol Med. 2002;8:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich H, Weissenborn K, Prange H, Schneider D, Weimar C, Wartenberg K, Schellinger PD, Bohn M, Becker H, Wegrzyn M, Jahnig P, Herrmann M, Knauth M, Bahr M, Heide W, Wagner A, Schwab S, Reichmann H, Schwendemann G, Dengler R, Kastrup A, Bartels C. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:e647–656. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S, Egrie J, Browne J, Lorenzini T, Busse L, Rogers N, Ponting I. Control of rHuEPO biological activity: the role of carbohydrate. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:1146–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario M, Massa M, Rosti V, Campanelli R, Ferlini M, Marinoni B, De Ferrari GM, Meli V, De Amici M, Repetto A, Verri A, Bramucci E, Tavazzi L. Early haemoglobin-independent increase of plasma erythropoietin levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1805–1813. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förstermann U, Schmitt HHHW, Pollock JS, Sheng H, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Nakane M, Murrad F. Isoforms of nitric oxide synthase: characterization and purification from different cell types. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:1849–1857. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90581-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc S, Koroglu TF, Genc K. Erythropoietin and the nervous system. Brain Res. 2004;1000:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali JK, Anand IS, Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Greenberg B, Krum H, Massie BM, Wasserman SM, Trotman ML, Sun Y, Knusel B, Armstrong P. Randomized double-blind trial of darbepoetin alfa in patients with symptomatic heart failure and anemia. Circulation. 2008;117:526–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso G. An overview of new pharmacological treatments for cerebrovascular dysfunction after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;44:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso G, Buemi M, Alafaci C, Sfacteria A, Passalacqua M, Sturiale A, Calapai G, De Vico G, Piedimonte G, Salpietro FM, Tomasello F. Beneficial effects of systemic administration of recombinant human erythropoietin in rabbits subjected to subarachnoid hemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5627–5631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082097299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso G, Sfacteria A, Cerami A, Brines M. Erythropoietin as a tissue-protective cytokine in brain injury: what do we know and where do we go? Neuroscientist. 2004;10:93–98. doi: 10.1177/1073858403259187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross ER, Gross GJ. Ligand triggers of classical preconditioning and postconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstenson CE, Macres M, Katz SA, Schnieders JR, Watanabe M, Sobota JT, Abraham PA. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of epoetin alfa and epoetin beta. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;50:702–712. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 1994;89(Suppl 1):87–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85660-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T, Richardson D, Oberley L, Katusic Z. Erythropoietin increases expression of CuZn superoxide dismutase in endothelial progenitor cells. Stroke. 2005;36:426. [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen C, Aicher A, Lehmann R, Fichtlscherer S, Vasa M, Urbich C, Mildner-Rihm C, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Erythropoietin is a potent physiologic stimulus for endothelial progenitor cell mobilization. Blood. 2003;102:1340–1346. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata A, Minamino T, Asanuma H, Fujita M, Wakeno M, Myoishi M, Tsukamoto O, Okada K, Koyama H, Komamura K, Takashima S, Shinozaki Y, Mori H, Shiraga M, Kitakaze M, Hori M. Erythropoietin enhances neovascularization of ischemic myocardium and improves left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ. Biosynthesis and metabolism of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;30:535–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen PO, Nicolaysen A, Kvernebo K, Benestad HB, Nicolaysen G. Human cytokines modulate arterial vascular tone via endothelial receptors. Pflugers Arch. 1999;439:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s004249900149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K, Shoemaker C, Rudersdorf R, Neill SD, Kaufman RJ, Mufson A, Seehra J, Jones SS, Hewick R, Fritsch EF, et al. Isolation and characterization of genomic and cDNA clones of human erythropoietin. Nature. 1985;313:806–810. doi: 10.1038/313806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janmaat ML, Heerkens JL, de Bruin AM, Klous A, de Waard V, de Vries CJ. Erythropoietin accelerates smooth muscle cell-rich vascular lesion formation in mice through endothelial cell activation involving enhanced PDGF-BB release. Blood. 2010;115:1453–1460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelkmann W. Erythropoietin: structure, control of production, and function. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:449–489. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin DK, Shido K, Kopp HG, Petit I, Shmelkov SV, Young LM, Hooper AT, Amano H, Avecilla ST, Heissig B, Hattori K, Zhang F, Hicklin DJ, Wu Y, Zhu Z, Dunn A, Salari H, Werb Z, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Lyden D, Rafii S. Cytokine-mediated deployment of SDF-1 induces revascularization through recruitment of CXCR4+ hemangiocytes. Nat Med. 2006;12:557–567. doi: 10.1038/nm1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joannides R, Bakkali EH, Le Roy F, Rivault O, Godin M, Moore N, Fillastre JP, Thuillez C. Altered flow-dependent vasodilatation of conduit arteries in maintenance haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2623–2628. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.12.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagy NL, Perrine MF, Cheung DK, Walker BR. Erythropoietin administration in vivo increases vascular nitric oxide synthase expression. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42:527–533. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Amano H, Ito Y, Eshima K, Aoyama N, Tamaki H, Sakagami H, Satoh Y, Izumi T, Majima M. Effect of erythropoietin on angiogenesis with the increased adhesion of platelets to the microvessels in the hind-limb ischemia model in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:167–175. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09262fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapholz M, Abraham WT, Ghali JK, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Knusel B, Sun Y, Wasserman SM, van Veldhuisen DJ. The safety and tolerability of darbepoetin alfa in patients with anaemia and symptomatic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:1071–1077. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Minatoguchi S, Yasuda S, Bao N, Kawamura I, Iwasa M, Yamaki T, Sumi S, Misao Y, Ushikoshi H, Nishigaki K, Takemura G, Fujiwara T, Tabata Y, Fujiwara H. Post-infarct treatment with an erythropoietin-gelatin hydrogel drug delivery system for cardiac repair. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:611–620. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapf R, Hulter HN. Arterial hypertension induced by erythropoietin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:470–480. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05040908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama S, Hopp L, Yoshida H, Hikita M, Tomonari H, Hashimoto T, Sakai O. Evidence for amelioration of endothelial cell dysfunction by erythropoietin therapy in predialysis patients. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9:426–431. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai PH, Everett R, Wang FF, Arakawa T, Goldwasser E. Structural characterization of human erythropoietin. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:3116–3121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CF, Peterson TE, Richardson DM, Croatt AJ, d’Uscio LV, Nath KA, Katusic ZS. Increased blood flow causes coordinated upregulation of arterial eNOS and biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H786–793. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00759.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Okada H, Takemura G, Esaki M, Kobayashi H, Kanamori H, Kawamura I, Maruyama R, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H, Tabata Y, Minatoguchi S. Sustained release of erythropoietin using biodegradable gelatin hydrogel microspheres persistently improves lower leg ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2378–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Takemura G, Okada H, Miyata S, Maruyama R, Li L, Higuchi M, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Reduction of inflammatory cytokine expression and oxidative damage by erythropoietin in chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FK, Suggs S, Lin CH, Browne JK, Smalling R, Egrie JC, Chen KK, Fox GM, Martin F, Stabinsky Z, et al. Cloning and expression of the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7580–7584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenblatt N, Menger MD, Klar E, Vollmar B. Darbepoetin-alpha does not promote microvascular thrombus formation in mice: role of eNOS-dependent protection through platelet and endothelial cell deactivation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1191–1198. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli F, Villa G, de Francisco AL, Albertazzi A, Adrogue HJ, Dougherty FC, Beyer U. Effect of a continuous erythropoietin receptor activator (C.E.R.A.) on stable haemoglobin in patients with CKD on dialysis: once monthly administration. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:969–979. doi: 10.1185/030079907x182103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Ongil SL, Saura M, Lamas S, Rodriguez Puyol M, Rodriguez Puyol D. Recombinant human erythropoietin does not regulate the expression of endothelin-1 and constitutive nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. Exp Nephrol. 1996;4:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher TF, Vanhoutte PM. The Endothelium: Modulator of Cardiovascular Function. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall I. An overview of the efficacy and safety of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(Suppl 3):14–21. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_3.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC, Eckardt KU. Novel strategies for stimulating erythropoiesis and potential new treatments for anaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:947–953. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC, Gray SJ, Elston O, Breen C, Jenkins B, Browne J, Egrie J. Pharmacokinetics of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein compared with epoetin alfa in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2392–2395. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC, Padhi D, Jang G. Pharmacology of darbepoetin alfa. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 4):iv2–iv9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC, Roberts DE, Coles GA, Williams JD. Clinical pharmacokinetics of epoetin (recombinant human erythropoietin) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1991;20:99–113. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199120020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC, Robson R, Opatrna S, Liogier X, Pannier A, Jordan P, Dougherty FC, Reigner B. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Intravenous and Subcutaneous Continuous Erythropoietin Receptor Activator (C.E.R.A.) in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1211–1215. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00730306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini DM, Katz SD, Lang CC, LaManca J, Hudaihed A, Androne AS. Effect of erythropoietin on exercise capacity in patients with moderate to severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:294–299. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044914.42696.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Okano M, Yamagishi K, Nagao M, Ueda M, Sasaki R. A novel site of erythropoietin production.Oxygen-dependent production in cultured rat astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19488–19493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon F, Vargas R, Ryan M, Jain A, Abels R, Perry B, Smith I. Pharmacokinetics and effects of recombinant human erythropoietin after intravenous and subcutaneous injections in healthy volunteers. Blood. 1990;76:1718–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Miura T, Hotta H, Tanno M, Yano T, Sato T, Terashima Y, Takada A, Ishikawa S, Shimamoto K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic hearts abolishes erythropoietin-induced myocardial protection by impairment of phospho-glycogen synthase kinase-3beta-mediated suppression of mitochondrial permeability transition. Diabetes. 2009;58:2863–2872. doi: 10.2337/db09-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura O, Nakamura N, Ihle JN, Aoki N. Erythropoietin-dependent association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with tyrosine-phosphorylated erythropoietin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994a;269:614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura O, Nakamura N, Quelle FW, Witthuhn BA, Ihle JN, Aoki N. Erythropoietin induces association of the JAK2 protein tyrosine kinase with the erythropoietin receptor in vivo. Blood. 1994b;84:1501–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake T, Kung CK, Goldwasser E. Purification of human erythropoietin. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5558–5564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C, Krawczyk M, Ahn D, Ahmet I, Paik D, Lakatta EG, Talan MI. Erythropoietin reduces myocardial infarction and left ventricular functional decline after coronary artery ligation in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11612–11617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1930406100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Lariviere R, Kingma I, Grose JH, Lebel M. Chronic nitric oxide inhibition aggravates hypertension in erythropoietin-treated renal failure rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2000;22:663–674. doi: 10.1081/ceh-100101998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano M, Satoh K, Fukumoto Y, Ito Y, Kagaya Y, Ishii N, Sugamura K, Shimokawa H. Important role of erythropoietin receptor to promote VEGF expression and angiogenesis in peripheral ischemia in mice. Circ Res. 2007;100:662–669. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260179.43672.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiuchi S, Kagaya Y, Ohta J, Shiba N, Sugi M, Oikawa M, Kunii H, Yamao H, Komatsu N, Yui M, Tada H, Sakuma M, Watanabe J, Ichihara T, Shirato K. High serum erythropoietin level is associated with smaller infarct size in patients with acute myocardial infarction who undergo successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1406–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusser M, Tepel M, Zidek W. Erythropoietin increases cytosolic free calcium concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1233–1236. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z, Wang XQ, Vaziri ND. Nitric oxide metabolism in erythropoietin-induced hypertension: effect of calcium channel blockade. Hypertension. 1998;32:724–729. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol CA, Smith GK, Duch DS. Biosynthesis and metabolism of tetrahydrobiopterin and molybdopterin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:729–764. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara M, Miura T, Miki T, Sakamoto J, Tanno M, Kobayashi H, Ikeda Y, Ohori K, Takahashi A, Shimamoto K. Erythropoietin affords additional cardioprotection to preconditioned hearts by enhanced phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H748–755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00837.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi CT, Bae KS, Chin K, Wada Y, Schechter AN, Hankins WD. Cloning of the human erythropoietin receptor gene. Blood. 1991;78:2548–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Yamashiro S, Matsuzaki T, Sakanashi M, Nakasone J, Miyagi K. Effect of 1-week treatment with erythropoietin on the vascular endothelial function in anaesthetized rabbits. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:395–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzuoli A, Silverberg D, Iovine F, Capobianco S, Giannotti G, Calabro A, Campagna SM, Nuti R. Erythropoietin improves anemia exercise tolerance and renal function and reduces B-type natriuretic peptide and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and anemia. Am Heart J. 2006;152:1096 e1099–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RMJ, Ashton DS, Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664–666. doi: 10.1038/333664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RMJ, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa CJ, Matsumoto A, Kim J, Riel RU, Pascal LS, Walton GB, Thompson RB, Petrofski JA, Annex BH, Stamler JS, Koch WJ. A novel protective effect of erythropoietin in the infarcted heart. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:999–1007. doi: 10.1172/JCI18200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JS, Förstermann U, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Schmidt HH, Nakane M, Murad F. Purification and characterization of particulate endothelium-derived relaxing factor synthase from cultured and native bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10480–10484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Szachniewicz J, Okonko D, Ledwidge M, Zymlinski R, Ryan E, Wasserman SM, Baker N, Rosser D, Rosen SD, Poole-Wilson PA, Banasiak W, Coats AJ, McDonald K. Effect of darbepoetin alfa on exercise tolerance in anemic patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano R, Besarab A, Macdougall IC, Ellison DH, Maxwell AP, Sulowicz W, Klinger M, Rutkowski B, Correa-Rotter R, Dougherty FC. The continuous erythropoietin receptor activator (C.E.R.A.) corrects anemia at extended administration intervals in patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis: results of a phase II study. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67:306–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaschning T, Ruschitzka F, Stallmach T, Shaw S, Morawietz H, Goettsch W, Hermann M, Slowinski T, Theuring F, Hocher B, Lüscher TF, Gassmann M. Erythropoietin-induced excessive erythrocytosis activates the tissue endothelin system in mice. FASEB J. 2003;17:259–261. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0296fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee P, Shi Y, Su J, Pritchard KA, Jr, Tweddell JS, Baker JE. Erythropoietin protects the infant heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by triggering multiple signaling pathways. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan R, Cheung WK, Wacholtz MC, Minton N, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after single and multiple doses in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:991–1002. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman CS, Li H, Martasek P, Kral V, Masters BS, Poulos TL. Crystal structure of constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a paradigm for pterin function involving a novel metal center. Cell. 1998;95:939–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81718-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport RM, Draznin MB, Murad F. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat aorta may be mediated through cyclic GMP-dependent protein phosphorylation. Nature. 1983;306:174–176. doi: 10.1038/306174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond TD, Chohan M, Barber DL. Turning cells red: signal transduction mediated by erythropoietin. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui T, Feng Q, Lei M, Peng T, Zhang J, Xu M, Abel ED, Xenocostas A, Kvietys PR. Erythropoietin prevents the acute myocardial inflammatory response induced by ischemia/reperfusion via induction of AP-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruschitzka FT, Wenger RH, Stallmach T, Quaschning T, de Wit C, Wagner K, Labugger R, Kelm M, Noll G, Rulicke T, Shaw S, Lindberg RL, Rodenwaldt B, Lutz H, Bauer C, Lüscher TF, Gassmann M. Nitric oxide prevents cardiovascular disease and determines survival in polyglobulic mice overexpressing erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11609–11613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadamoto Y, Igase K, Sakanaka M, Sato K, Otsuka H, Sakaki S, Masuda S, Sasaki R. Erythropoietin prevents place navigation disability and cortical infarction in rats with permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:26–32. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]