The overall goals of sedation in the critical care setting are to provide physiologic stability and patient comfort.1-4 The need for sedative therapy in mechanically ventilated (MV) patients in adult critical care settings is well established with 85% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients receiving sedation to promote patient comfort by attenuating the anxiety, pain, and agitation associated with mechanical ventilation.2, 3, 5, 6 For most critically ill patients, a strategy that ensures patient comfort while maintaining a light level of sedation is associated with improved clinical outcomes.7-12 However, striving to ensure that patients are free from pain, agitation and anxiety may conflict with maintaining cardiopulmonary stability13 since medications that enhance comfort and reduce agitation and anxiety may also contribute to cardiopulmonary instability. Although sedatives are among the most frequently prescribed drugs in intensive care,14 the achievement and evaluation of optimal sedation remains a clinical challenge.

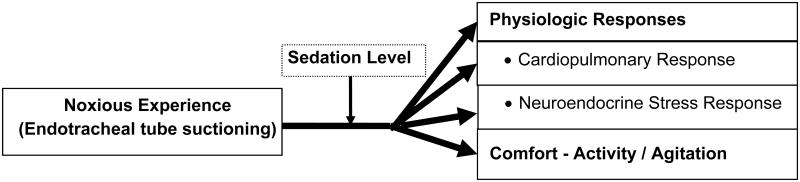

Sedative medications should reduce the physiologic stress of respiratory failure and improve the tolerance of invasive life support.2, 15-17 However, noxious experiences such as endotracheal tube suctioning18-22 may produce stressful stimuli, even in the presence of sedation, resulting in increases in both beta-endorphin23 and catecholamine blood levels, tachycardia and hypertension.24 Although noxious experiences may be unavoidable in critical care, whether sedation ameliorates their negative effects has not been well examined and identification of strategies to reduce the stress response to critical illness is a priority.25 Therefore, the specific aim of this study was to determine the effect of sedation on physiologic responses and comfort during and after a noxious stimulus, specifically, endotracheal suctioning.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

This study is a subset of a larger, prospective, 24 hour, observational study conducted in a 779-bed tertiary care university medical center in 3 critical care units, Surgical Trauma ICU (STICU), Cardiac Surgery ICU (CSICU) and Medical Respiratory ICU (MRICU).26 The specific aim of the larger prospective study was to describe the relationship among sedation, stability of physiological status, and comfort during a 24- hour period in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. The larger study sample (N=176) was drawn from all patients admitted to these ICUs who were intubated, MV, 18 years of age or older, and with an expectation of at least 24 hours of mechanical ventilation. Patients were excluded who had a tracheostomy (rather than endotracheal intubation) since the discomfort associated with a tracheostomy tube may be different than that associated with an endotracheal tube (ETT),27 received paralytics, had a chronic, persistent neuro-muscular disorders (such as cerebral palsy and Parkinson’s disease) or had suffered head trauma or stroke as these would affect patient movement and study measurements. Subjects were recruited over a 2-year data collection period. The subset of 67 subjects for the study reported here were those who had an endotracheal tube (ETT) suctioning event during daytime hours when study research assistants were present, had venous access, and a hemoglobin level greater than 7.0 gm/dL to reduce risks associated with lowering of hemoglobin levels with additional venous sampling.

Key Variables and their Measurement

Sedation

The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) is a 10 point scale, ranging from −5 (unarousable) to 0 (calm and alert) to +4 (combative), based on observations of specific patient behaviors.28 This scale is used widely in critical care, demonstrates excellent interrater reliability and criterion, construct, and face validity. It is the first sedation scale to be validated for its ability to detect changes in sedation status over consecutive days of ICU care, against constructs of level of consciousness and delirium, and correlated with the administered dose of sedative and analgesic medications.28, 29 The RASS was found to have the highest physiometric score of all sedation scales included in a recent review.3 The RASS served as our baseline measure of sedation prior to suctioning. Based on our previous work, and the RASS descriptions, a RASS of −5, −4, or −3 was categorized as moderate/deeply sedated, a −2, −1 or 0 as alert/mildly sedated and a +1, +2, +3, or +4 was categorized as restless/agitated.28, 30 To determine the effect of all levels of sedation including a RASS level of alert, all subjects regardless of RASS level, were included.

Physiologic Response

Cardiopulmonary Response

This response was measured as heart rate (HR), oxygenation (respiratory rate [RR], hemoglobin saturation of oxygen [SPO2]). Heart rate data were acquired every second using the Criticare Systems Scholar II monitor (Criticare Systems, INC, Waukesha, WI), using a Type I, three electrode ECG sensors, which were stored in the computer via serial port connection. Respiratory rate information was documented for every breath and was acquired from the ventilator through a NICO® Cardiopulmonary Monitor device (Respironics, Parsippany, NJ) then stored to the computer via serial port connection. The SPO2 waveform from the NICO® monitor was obtained from a finger oximetry sensor. The analog SPO2 signal was then sampled and stored on the PC at a rate of 125 Hz using a Biopac™ Systems (Goleta, CA) MP-150 data acquisition system. The stored SPO2 data were averaged into one second intervals and then time-synchronized with the respiratory, HR and actigraphy data into a single text file.

Neuroendocrine Stress Response

Serum beta-endorphin and salivary alpha-amylase levels are markers of the stress response and were selected because they reflect central nervous system response (beta-endorphin) and sympathetic nervous stimulation (salivary alpha-amylase), can be reliably measured, and have been used successfully in critically ill populations.31, 32 Blood samples were drawn after a 30 minute period without stimulation (i.e., no physical stimulation and the subject appeared restful) and within 1 minute after ETT suctioning. Each three ml sample was collected in a tube containing EDTA and Trasylol and immediately placed on ice; plasma was separated by refrigerated centrifugation, and frozen at −70° C within one hour of collection. Beta-endorphin was assayed by commercially available radio-immunoassay (RIA) kit (IBI Products, Hamburg, Germany), which demonstrates excellent specificity and is able to quantify beta-endorphin in ranges expected in this clinical study.

Salivary alpha-amylase was measured using a parotid sample of saliva and was collected by plain (non-citric acid) cotton salivettes (Sarstedt Inc, Newton, NC), the preferred method of collection for this biological marker.32 Saliva samples were obtained at the same times that blood samples for beta-endorphin were drawn. With the head of bed elevated at least 45 degrees, the salivette was placed in the buccal pocket of the subject’s oral cavity, where it remained for 2 minutes. The salivette was then sealed in its transport tube and delivered to the laboratory. Saliva samples were frozen at −20°C in order to precipitate mucins and to preserve stability. Prior to analysis, samples were thawed completely, vortexed, and centrifuged. Salivary alpha-amylase was quantified by a commercially available assay kit (Salimetrics, State College, PA) which utilized a chromagenic substrate to demonstrate the enzymatic action of alpha-amylase. The amount of α-amylase activity present in the sample is directly proportional to the increase in spectrophotometric absorbance.

Comfort

Patient comfort is a goal of sedation use. While analgesics are used specifically for pain relief, sedation together with analgesia may be required in the critically ill adult to alleviate pain and distress associated with surgical and other invasive or diagnostic procedures, to improve the efficacy of mechanical ventilation, and to alleviate the distress associated with acute illnesses, that is, to improve overall patient comfort. In the mechanically ventilated adult, it is often difficult to distinguish pain from anxiety, agitation or distress. Certainly patients in pain need first to be treated to reduce pain. However, evaluating pain, especially in the non-communicative, mechanically ventilated critically ill population continues to be difficult.33, 34 Patients display a variety of behaviors that are associated with discomfort, including movement or restlessness.22 Indeed, the most promising pain assessment tools for this population, the Behavioral Pain Scale35, 36 and the Critical Care Pain Observation tool,37 both contain parameters for measuring patient movement. In addition, patient movement is often used in sedation evaluation and has shown to have the greatest influence in judgments of the sedation adequacy.2 Therefore the use of patient movement, especially in the non-communicative or intubated patient as a marker of discomfort may be appropriate. Further, for the larger study from which this report was drawn, required a continuous measure of patient comfort, and therefore the use of typical, intermittently measured comfort-discomfort, sedation or pain scales was not possible.

Wrist and ankle actigraphy were used to record activity level as a surrogate measure of comfort. The actigraphy monitor contains a single omnidirectional accelerometer that integrates occurrence, degree and intensity of motion to produce activity counts and is capable of sensing any motion with minimal acceleration of 0.01 g. Actigraphy has been used to monitor activity levels in subjects for sleep, circadian rhythms, pain, or drug response and has recently been found by our research team30 and others38 to be a reliable method of assessing activity/agitation in the critical care setting.

In a prospective evaluation of 20 adult medical ICU patients, we found that actigraphy was sensitive to changes in sedation and comfort and significantly correlated with the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) (R = 0.58; p < 0.001), and the Comfort Scale (R = 0.62; p < 0.05).30 We have also identified actigraphic levels that correspond to a variety of behavior states (calm, restless, agitated) in a sample of volunteers that simulated behaviors often exhibited in the critically ill and may reflect patient comfort.39 Wrist and ankle actigraphy data were acquired through MotionLoggerR Actigraphy devices (Basic Octagonal Motionlogger, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY) using the proportional integrating measurement (PIM) mode of operation. Under PIM mode, a numerical scale of movement activity was created based on the absolute value of the area under the curve, defined by the output signal of the accelerometer within the sensor. The movement scale can range from 0 to 32,000 and provides a measure of movement intensity. A value of zero indicates a state of no movement and rest while the maximum scale value corresponds to vigorous, maximum movement of the sensor and limb. In our previous work39, mean actigraphic counts were identified based on level of movement for the arm (calm = 6.80; restless = 28.5; agitated = 52.6) and leg (calm = 3.5; restless = 18.7; agitated = 37.7).

On study setup, the internal time of the Motionlogger was synchronized to the time of computer clock. Motion data was recorded every second and were later downloaded through a serial port connection to the computer for later analysis.

Demographic characteristics

Subject characteristics were documented and included subject’s age, ICU (reflecting type of critical illness and population; i.e. surgical, medical, cardiac surgery), duration of endotracheal intubation (in hours), ICU length of stay (in hours), as well as type and amount of sedative and analgesic administered. Severity of illness was documented on study enrollment in adults using the APACHE.40

Procedures

The study was approved by the institutional IRB and informed consent was obtained from each subject’s legally authorized representative (LAR). Subjects were enrolled during any period of mechanical ventilation as long as the inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. This subset of data was collected during the 24-hour period of the larger study, and occurred on any day of mechanical ventilation. Prior to physiologic data collection and monitoring, all devices and monitors were time synchronized and time stamped with respect to the computer’s real-time clock. The acquired data were stored and regularly inspected and reviewed for quality, accuracy and integrity to reduce variability in subject measures.

Suctioning Process

Suctioning occurred only as deemed necessary by the bedside care provider based on patient needs and not at any set time interval. Continuous data collection (including measures of HR, RR, SPO2, and arm and leg actigraphy) occurred for the larger study during a continuous 24 hour period, and direct patient observations occurred during a four hour block within the 24 hour period. Therefore research assistants were present to document the suctioning event (at some point during the 4 hour observation) and all continuously recorded data (HR, RR, SPO2, and arm and leg actigraphy) were therefore available for this subset. Data were downloaded for a 30 minute rest period prior to suctioning, during one suctioning event, and for 30 minutes after suctioning (Figure 2). ETT suctioning and sample collection occurred in a standard order. First, plasma was drawn for beta-endorphins (through the intravenous access device), salivary samples were obtained for alpha-amylase levels, and RASS data were collected by study personnel last. In order to score the RASS, the subject must be stimulated to respond if not obviously awake and alert. Therefore, collection of the RASS data occurred after all other data for each data collection period had occurred so the stimulation required for scoring the RASS would not affect the other measures. The total study time was therefore 65 minutes for each subject.

Figure 2.

Study Procedure for each Subject

Data Analysis

Measurement intervals vary for the factors under study. Some factors vary only between subjects (i.e., demographics & disease severity), and other factors vary within a subject across time (i.e. level of sedation). Data were collected every second for physiologic and actigraphy data and were averaged within 12 second intervals to provide a common epoch across measures, and to smooth the data. The mean value for each variable during every 12 second interval was then used for each analysis. For each subject and for each measure, this process resulted in a single observation every 12 second for 65 minutes, yielding a total of approximately 325 observations per subject.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the subject characteristics. The mean HR, RR, SPO2, and arm and leg actigraphy values 30 to 5 minutes prior to suctioning were computed and used as baseline physiologic measures. After the suctioning event, the mean HR, RR, SPO2, and arm and leg actigraphy values were computed based on 1 minute averages taken at times 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes post suctioning.

Generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMM) were used to test relationships among beta-endorphins, salivary alpha-amylase, and the physiologic response measures of HR, RR, SPO2, and arm and leg actigraphy. Two GLMMs were used to model changes in endorphins and salivary alpha-amylase pre to post suctioning. These models included fixed effects for time (pre or post suctioning), baseline RASS (moderate/deeply sedated, alert/mildly sedated, restless/agitated)30 and the time by baseline RASS interaction effect. A random subject effect was included to account for the within-subject correlations in the pre to post measures of endorphins and salivary amylase. Another 5 GLMMs were used to model the changes in the physiologic response measures over time. These models included fixed effects for post suctioning time period (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 30 minutes, baseline RASS (moderate/deeply sedated, alert/mildly sedated, restless/agitated), and the time by baseline interaction effect. Furthermore, each model adjusted for its respective baseline physiologic measure (e.g. the model for HR included baseline HR measured 30 to 5 minutes pre-suctioning). For these 5 models, the within-subject associations were modeled assuming a spatial power correlation structure for the residuals. In general, normal distributions and identity link functions were assumed; with the exception of salivary amylase, which assumed a log-normal distribution, and the actigraphy measures for arm and leg which assumed an over-dispersed Poisson distribution. Poisson regression is used to model counts that are highly skewed. Using all 7 models, tests of the hypotheses were performed as follows. First the interaction between time and baseline RASS was tested. A significant interaction effect was indicative that the changes in the response variable over time depend on (are modified by) level of sedation as measured by baseline RASS. In these cases, changes in the response over time were estimated and tested separately for each RASS group. If the interaction was not significant, then there was no evidence suggesting that level of sedation depends on RASS and thus changes over time were estimated irrespective of (averaged over) RASS groups.

RESULTS

The characteristics of this sample of the 67 subjects are summarized in Table 1. Subjects had a mean age of 55 (SD = 15.3), were equally split between male and female and primarily African American or White with the majority of subjects being from the MRICU. Mean APACHE scores along with median duration of intubation and median length of ICU stay are also shown in Table 1. The distribution of baseline RASS scores indicated that subjects were moderately/deeply sedated (n = 25, 37%), alert/mildly sedated (n = 36, 54%) or restless/agitated (n = 6, 9%). Means are reported for variables that were normally distributed, while medians are reported for skewed distributions (Table 1). Subjects received both analgesics (70% received fentanyl, 15% morphine, 1% hydromorphone) and sedatives (49% received midazolam, 18% propofol, 14% lorazepam, 2% haloperidol).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 55.1 | 15.3 | 21 to 83 |

| APACHE III | 74.5 | 25.7 | 26 to 147 |

|

| |||

|

| |||

| Median | IQR | Range | |

|

| |||

| Length of Intubation (days) | 7.9 | 4.2 to 14.1 | 1.7 to 30.0 |

| ICU Length of Stay (days) | 13.8 | 9.3 to 20.2 | 4.1 to 64.7 |

| Length of Intubation at Study Enrollment (days) | 2.4 | 1.4 to 5.3 | 0.01 to 19.6 |

|

| |||

| Count | Percent | ||

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 33 | 49.3 | |

| Female | 34 | 50.7 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 30 | 44.8 | |

| Black/African American | 33 | 49.3 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Unknown/Not Reported | 3 | 4.5 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 2 | 3.0 | |

| Non-Hispainc | 65 | 97.0 | |

| Critical Care Unit | |||

| MRICU | 43 | 64.2 | |

| STICU | 18 | 26.9 | |

| CSICU | 6 | 9.0 | |

|

| |||

SD = Standard Deviation; IQR = Interquartile Range

Salivary Alpha-Amylase and Serum Beta-Endorphins

There was no evidence that the changes in log salivary alpha-amylase (p = 0.90) or serum beta-endorphins (p = 0.38) were modified by level of sedation (Table 2). The mean alpha-amylase value (on the natural scale) was nearly 3 times higher post suctioning than pre-suctioning (p = 0.0432), however the increase in mean beta-endorphin values was only nominal (p = 0.18).

Table 2.

Changes in Salivary Alpha-amylase and Serum Beta-Endorphins over Time

| Natural Scale |

Log scale |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Time | LS Mean |

SE | 95% CI | Time | LS Mean |

SE | 95% CI |

|

| ||||||||

| Salivary Alpha- amylase |

Pre | 12.34 | * | (3.51, 43.35) | Pre | 2.51 | 0.61 | (1.26, 2.77) |

| Post | 36.80 | * | (13.34,101.53) | Post | 3.60 | 0.49 | (2.59, 4.62) | |

| Post- Pre |

2.98 | * | (1.04, 8.56) † | Post- Pre |

1.90 | 0.49 | (0.04, 2.15) | |

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Beta- Endorphins |

Pre | 0.87 | 0.12 | (0.62, 1.11) | Pre | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Post | 0.96 | 0.22 | (0.53, 1.40) | Post | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Post- Pre |

0.09 | 0.18 | (−0.26, 0.44) | Post- Pre |

N/A | N/A | N/A | |

|

| ||||||||

Pre=prior to suctioning; Post=after suctioning; Post-Pre= Post minus Pre; LS = Least Squares; SE = Standard Error; CI = Confidence Interval; N/A = Not Applicable;

Statistically significant at α = 0.05;

SE shown on the log scale.

Physiologic Responses and Comfort

There was no evidence that the changes in HR (p = 0.90), RR (p = 0.88), or SPO2 (p = 0.24) post suctioning were modified by level of sedation due to the lack of significant interaction effects between time and baseline RASS. There were also no significant changes in the mean HR (p = 0.99), mean RR (p = 0.97), or mean SPO2 (p = 0.24) over time post suctioning.

When modeling actigraphy measures in a sedated population it is important to understand that many subjects do not move, so that a large number of responses will be 0, representing no movement. Values greater than zero proportionally represent the amount of movement measured in the arm and the leg of the subject. To account for the immobility of many subjects, zero-inflated generalized Poisson models were fit for these responses. Observation of the arm and leg actigraphy data by RASS score and time period indicated that there was no variability at 1, 4, and 5 minutes post suctioning for some RASS categories (due to no movement), resulting in poor fitting models. Thus, we excluded these time points prior to fitting the Poisson models. Arm (p=0.007) and leg actigraphy (p=0.057) changed from baseline and there was significant evidence that changes in arm actigraphy (p = 0.0004) were modified by level of sedation; however changes in leg actigraphy were not (p = 0.92). The trends over time post suctioning (0 to 30 minutes after suctioning) by level of sedation are displayed in Figure 3. There were significant changes in arm actigraphy for those who were restless/agitated (p = 0.0063) and moderately/deeply sedated (p = < 0.0001) but not for those who were alert/mildly sedated (p = 0.49). There was no evidence of changes in leg actigraphy post suctioning for those who were restless/agitated (p = 0.67), alert/mildly sedated (p = 0.86), or moderately/deeply sedated (p = 0.86) for the entire sample irrespective of level of sedation (overall p = 0.78). Smaller standard errors in the arm measurement permitted the differences to be more evident in the upper panel (arm) of Figure 3, while greater variability in leg actigraphy (lower panel; leg) made it difficult to detect changes.

Figure 3. Actigraphy Count Change from Baseline in Arm and Leg Actigraphy Over Time in Minutes Post-Suctioning by Level of Sedation.

Mean change in actigraphy counts for arm and leg actigraphy for the three sedation states over time from the suctioning event through 30 minutes after the suctioning event. Data points at 2, 10, 15, and 30 minutes after suctioning are indicated by the corresponding sedation level symbol. Smaller standard errors in the arm measurement permitted the differences to be more evident while greater variability in leg actigraphy made it difficult to detect changes in this figure.

DISCUSSION

Optimal sedation, providing physiologic stability and comfort, is the goal for all patients since the use of inappropriately high or low levels of sedation in critically ill adults is accompanied by significant risks and oversedation, specifically, is a key factor in delayed recovery.8, 9, 41 For most critically ill patients, a strategy that ensures patient comfort while maintaining a light level of sedation improves clinical outcomes7, 8, 11, 12 and is recommended by the most recent national guidelines.3 The goals of sedation are to provide physiologic stability and patient comfort and should be achieved even during noxious stimuli. This prospective study described the effect of sedation on physiologic responses and comfort before, during and after a noxious stimulus, specifically, endotracheal suctioning. Our findings showed that while one marker of stress (salivary alpha-amylase) did increase during the noxious event, neither stress marker (salivary alpha-amylase nor serum beta-endorphin) was affected by the sedation level. Other physiologic measures (HR, RR or SPO2) did not change during suctioning and changes were not modified by sedation level.

This sample was a subset of a larger study and because suctioning events were identified based on issues related to logistics (time of day, RA present, venous access), it may not represent the larger population.26 The level of sedation differed between the two samples (this subset and the larger study) and with the present goal of lighter sedation, it may not fully reflect current practice. In addition, it is unknown whether the long duration of intubation and resulting stress response blunted the physiologic response to this noxious event. While the percent of subjects categorized as moderately/deeply sedated was similar between this study and the larger study (37% vs 42%), this sample consisted of more subjects who were alert/mildly sedated (54% vs 38%) and fewer subjects who were restless/agitated (9% vs 20%). However, similar to this study, other authors2, 42 have shown that approximately one-third to one-half of MV patients are still deeply sedated.

Previously endotracheal tube suctioning has been shown to be a noxious/stressful event19, 21, 22 and caused changes in physiologic responses.18, 43, 44 In contrast, however, in this study, changes in physiologic responses (HR, RR or SPO2) from baseline were not found and changes were not modified by sedation level. More recent studies of pain in the critically ill have found that physiologic responses (HR, RR, SPO2) may not be good or consistent markers of pain nor, potentially, of stress, and should be considered with caution.45, 46,47 While patients report endotracheal suctioning as one of the most painful experiences,21, 48 studies of pain (procedural and other types) in critically ill patients have shown that patient behaviors (grimacing, rigidity, wincing, shutting of eyes, verbalization, moaning, and clenching of fists) are more often associated with pain than physiologic markers (i.e. changes in HR, RR, SPO2)22, 49 which may explain the lack of findings related to physiologic responses to ETT suctioning in this study. These are critical findings to the clinician, who may expect changes in HR, RR, SPO2 to occur during painful / noxious events, when in fact, these changes may not be present and may therefore significantly affect pain management strategies.

As a marker of comfort in this study, arm activity (although not leg), did increase with suctioning and these changes were influenced by sedation level. These results add support to previous work that shows the best measure of sedation adequacy, especially related to comfort, may be patient movement. Weinert et al.2 found that patient activity (too much spontaneous activity or too little) had the greatest influence in nurses’ judgment of sedation adequacy. Since the goal is a patient who is easily arousable and calm,1, 3 some spontaneous movement should be expected, but increases in activity level may be an appropriate indication of discomfort and should be investigated further, not only as a measure of sedation, but potentially a measure of pain in the critically ill. These data further support the use of limb movements in behavioral pain tools such as the Behavioral Pain Scale35, 36 and the Critical Care Pain Observation tool.37

Although patient comfort is a goal for any patient in the clinical setting, optimizing comfort in the intubated, non-communicative patient can be challenging due to lack of direct measures of comfort in this population. While these data and others show that physiological markers may not be good indicators of discomfort, especially in the critically ill, behavioral measures such as limb movement (restlessness) may be an important alternative to identify and monitor patient discomfort. Presently actigraphy is primarily a research rather than a clinical tool, but in the future, advances in technology may provide methods to monitor patient movement and restlessness more globally. In fact researchers are developing continuous measurements of patient motion using digital video imaging processing that readily quantify all body movement.50 With additional research, these type of automatic, electronic systems may optimize medication delivery leading to reduced length of stay and improved outcomes.

Figure 1.

Study Model

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: National Institute of Nursing Research R01 NR009506, Grap, MJ (PI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Goodwin H, Lewin JJ, Mirski MA. 'Cooperative sedation': optimizing comfort while maximizing systemic and neurological function. Crit Care. 2012;16(2):217. doi: 10.1186/cc11231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinert CR, Calvin AD. Epidemiology of sedation and sedation adequacy for mechanically ventilated patients in a medical and surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):393–401. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254339.18639.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sessler CN, Varney K. Patient-focused sedation and analgesia in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133(2):552–565. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morandi A, Brummel NE, Ely EW. Sedation, delirium and mechanical ventilation: the 'ABCDE' approach. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(1):43–49. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283427243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wunsch H, Kress JP. A new era for sedation in ICU patients. JAMA. 2009;301(5):542–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook AD, Ahrens TS, Schaiff R, et al. Effect of a nursing-implemented sedation protocol on the duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(12):2609–2615. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quenot JP, Ladoire S, Devoucoux F, et al. Effect of a nurse-implemented sedation protocol on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2031–2036. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000282733.83089.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson BR, Mueller EW, Henson K, Branson RD, Barsoum S, Tsuei BJ. An analgesia-delirium-sedation protocol for critically ill trauma patients reduces ventilator days and hospital length of stay. J Trauma. 2008;65(3):517–526. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318181b8f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta S, Burry L, Martinez-Motta JC, et al. A randomized trial of daily awakening in critically ill patients managed with a sedation protocol: a pilot trial. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(7):2092–2099. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817bff85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O'Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(20):1471–1477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treggiari MM, Romand JA, Yanez ND, et al. Randomized trial of light versus deep sedation on mental health after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2527–2534. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a5689f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milbrandt EB, Angus DC. Bench-to-bedside review: critical illness-associated cognitive dysfunction--mechanisms, markers, and emerging therapeutics. Crit Care. 2006;10(6):238. doi: 10.1186/cc5078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasta JF, Fuhrman TM, McCandles C. Patterns of prescribing and administering drugs for agitation and pain in patients in a surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(6):974–980. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199406000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinert CR, Chlan L, Gross C. Sedating critically ill patients: factors affecting nurses' delivery of sedative therapy. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(3):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhoney DH, Murry KR. National survey of the use of sedating drugs, neuromuscular blocking agents, and reversal agents in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2003;18(3):139–145. doi: 10.1177/0885066603251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta S, Burry L, Fischer S, et al. Canadian survey of the use of sedatives, analgesics, and neuromuscular blocking agents in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):374–380. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000196830.61965.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grap MJ, Glass C, Corley M, Creekmore S, Mellott K, Howard C. Effect of level of lung injury on HR, MAP and SaO2 changes during suctioning. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1994;10(3):171–178. doi: 10.1016/0964-3397(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JS, Briggs SJ, Springhorn HE, Potgieter PD. Patients' recollection of intensive care unit experience. Crit Care Med. 1990;18(9):966–968. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puntillo KA. Pain experiences of intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung. 1990;19(5 Pt 1):526–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puntillo KA, White C, Morris AB, et al. Patients' perceptions and responses to procedural pain: results from Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(4):238–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puntillo KA, Morris AB, Thompson CL, Stanik-Hutt J, White CA, Wild LR. Pain behaviors observed during six common procedures: results from Thunder Project II. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(2):421–427. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000108875.35298.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pokela ML, Koivisto M. Physiological changes, plasma beta-endorphin and cortisol responses to tracheal intubation in neonates. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(2):151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shribman AJ, Smith G, Achola KJ. Cardiovascular and catecholamine responses to laryngoscopy with and without tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59(3):295–299. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutschman CS, Ahrens T, Cairns CB, Sessler CN, Parsons PE. Multisociety Task Force for Critical Care Research: Key Issues and Recommendations. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21(1):15–23. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grap MJ, Munro CL, Wetzel PA, et al. Sedation in mechanically ventilated adults: Continuous measurement of physiologic and comfort outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grap MJ, Blecha T, Munro C. A description of patients' report of endotracheal tube discomfort. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18(4):244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0964339702000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring Sedation Status Over Time in ICU Patients: Reliability and Validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) JAMA. 2003;289(22):2983–2991. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grap MJ, Borchers CT, Munro CL, Elswick RK, Jr., Sessler CN. Actigraphy in the critically ill: correlation with activity, agitation, and sedation. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(1):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korak-Leiter M, Likar R, Oher M, et al. Withdrawal following sufentanil/propofol and sufentanil/midazolam. Sedation in surgical ICU patients: correlation with central nervous parameters and endogenous opioids. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(3):380–387. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nater UM, La MR, Florin L, et al. Stress-induced changes in human salivary alpha-amylase activity -- associations with adrenergic activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasero C, Puntillo K, Li D, et al. Structured approaches to pain management in the ICU. Chest. 2009;135(6):1665–1672. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puntillo K. Pain assessment and management in the critically ill: wizardry or science? Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):310–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(12):2258–2263. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chanques G, Payen JF, Mercier G, et al. Assessing pain in non-intubated critically ill patients unable to self report: an adaptation of the Behavioral Pain Scale. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2060–2067. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(4):420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mistraletti G, Taverna M, Sabbatini G, et al. Actigraphic monitoring in critically ill patients: preliminary results toward an "observation-guided sedation". J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grap MJ, Hamilton VA, McNallen A, et al. Actigraphy: Analyzing patient movement. Heart Lung. 2011;40(3):e52–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100(6):1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salluh JI, Soares M, Teles JM, et al. Delirium epidemiology in critical care (DECCA): an international study. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R210. doi: 10.1186/cc9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Payen JF, Chanques G, Mantz J, et al. Current Practices in Sedation and Analgesia for Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Patients: A Prospective Multicenter Patient-based Study. Anesth. 2007;106(4):687–695. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264747.09017.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson KL, Kearney PA, Johnson SB, Niblett JB, MacMillan NL, McClain RE. Closed versus open endotracheal suctioning: costs and physiologic consequences. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(4):658–666. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199404000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segar JL, Merrill DC, Chapleau MW, Robillard JE. Hemodynamic changes during endotracheal suctioning are mediated by increased autonomic activity. Pediatr Res. 1993;33(6):649–652. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199306000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelinas C, Johnston C. Pain assessment in the critically ill ventilated adult: validation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool and physiologic indicators. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(6):497–505. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31806a23fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gelinas C, Arbour C. Behavioral and physiologic indicators during a nociceptive procedure in conscious and unconscious mechanically ventilated adults: similar or different? J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):628–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arbour C, Gelinas C. Are vital signs valid indicators for the assessment of pain in postoperative cardiac surgery ICU adults? Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26(2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cazorla C, Cravoisy A, Gibot S, Nace L, Levy B, Bollaert PE. Patients' perception of their experience in the intensive care unit. Presse Med. 2007;36(2 Pt 1):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gelinas C, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Tanguay A, Bourgault P. Exploring the validity of the bispectral index, the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool and vital signs for the detection of pain in sedated and mechanically ventilated critically ill adults: a pilot study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chase JG, Agogue F, Starfinger C, et al. Quantifying agitation in sedated ICU patients using digital imaging. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;76(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]