Abstract

INTRODUCTION Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms and cholecystoenteric fistulae represent two rare complications of gallstone disease.

PRESENTATION OF CASE An 86 year old male presented to the emergency department with obstructive jaundice, RUQ pain and subsequent upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Upper GI endoscopy revealed bleeding from the medial wall of the second part of the duodenum and a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan revealed a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, concurrent cholecystojejunal fistula and gallstone ileus. This patient was successfully managed surgically with open subtotal cholecystectomy, pseudoaneurysm resection and fistula repair.

DISCUSSION To date there are very few cases describing haemobilia resulting from a bleeding cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. This report is the first to describe upper gastrointestinal bleeding as a consequence of two synchronous rare pathologies: a ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm causing haemobilia and bleeding through a concurrent cholecystojejunal fistula.

CONCLUSION Through this case, we stress the importance of accurate and early diagnosis through ultra- sonography, endoscopy, and contrast-enhanced CT imaging and emphasise that haemobilia should be included in the differential diagnosis of anyone presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. We have demonstrated the success of surgical management alone in the treatment of such a case, but accept that consideration of combined therapeutic approach with angiography be given in the first instance, when available and clinically indicated.

Keywords: Cystic Artery, Pseudoaneurysm, Cholecystojejunal fistula, Cholecystoenteric fistula

1. Introduction

Visceral pseudoaneurysms and cholecystoenteric fistulae represent two rare complications of gallstone disease. We present a unique case of a patient presenting with abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice and upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage resulting from a ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and concomitant cholecystojejunal fistula.

2. Case presentation

An 86-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department with a two-day history of colicky right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain associated with bilious vomiting. Relevant background included hypertension, diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolaemia. On examination, the patient was icteric with an associated pyrexia of 38 °C, hypotension and tachycardia. Abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness in the RUQ.

Laboratory investigation revealed raised inflammatory markers with a white blood cell count of 24.0 × 109 L−1 and C-reactive protein of 95 mg/L (Normal range: <7.5 mg/L). Liver function tests (LFTs) were also deranged with an alkaline phosphatase of 450 μ/L (46–111 μ/L), Alanine Transaminase of 142 μ/L (<45 μ/L) and Bilirubin of 60 μmol/L (<20 μmol/L). An ultrasound examination revealed a 5.7 cm calculus within the gallbladder surrounded by heterogeneous material; a diagnosis of cholangitis was made. The patient received fluid resuscitation with intravenous crystalloid and was commenced on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

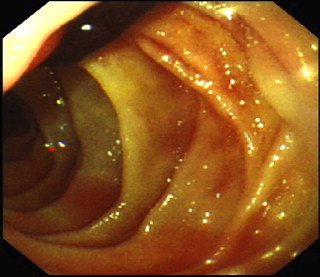

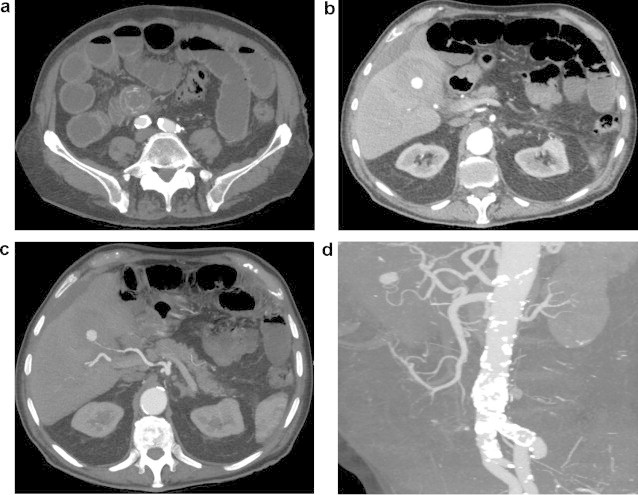

Subsequently, the patient passed a significant volume of malaena and fresh blood per rectum (PR), associated with cardiovascular instability. Emergency oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) revealed fresh blood in the second part of the duodenum and a tubular clot adherent to the medial wall (Fig. 1). This was assumed to be originating from a duodenal ulcer and apparent haemostasis was achieved with injection of 15 ml of 1:10,000 adrenaline. However, the patient continued to pass malaena and PR blood following the procedure. As such, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, demonstrating: (1) small bowel obstruction secondary to a gallstone impacted in the distal ileum (Fig. 2a) (2) a thick-walled and inflamed gallbladder with evidence of recent intra-cholecystic bleeding (Fig. 2b), and (3) a 12 mm pseudoaneurysm emanating from the cystic artery (Fig. 2c and d). In retrospect, the blood clot seen at OGD was likely to be haemobilia originating from the ampulla of Vater.

Fig. 1.

Second part of the duodenum viewed at OGD with a tubular clot adherent to medial wall, likely to be originating from the ampulla of vater.

Fig. 2.

Axial computed tomographic images with contrast demonstrating (a) small bowel obstruction secondary to a gallstone impacted in the distal ileum, (b) a thick-walled, inflamed gallbladder with evidence of recent intra-cholecystic bleeding, seen to be originating from (c) a 12 mm cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. This cystic artery pseudoaneurysm was further defined on CT angiography (d).

The patient underwent emergency laparoscopy and the gallbladder was found to be necrotic and surrounded with dense adhesions. Division of these exposed a cholecysto-jejunal fistula containing clotted blood that was extending into the gallbladder. Evacuation of this clot revealed a 1 cm × 2 cm pseudoaneurysm originating from the cystic artery, which began to bleed during dissection and the procedure was subsequently converted to an open laparotomy via a Kocher incision. A subtotal cholecystectomy was performed with oversewing of Hartmanns pouch and the aneurysm was successfully resected from the gallbladder fossa. The diseased jejunal loop was mobilised and the defect from the fistula was oversewn. Despite detailed examination of the small bowel, the gallstone located on CT could not be identified within the terminal ileum. The laparotomy wound was therefore closed under the assumption that the stone had passed spontaneously. The patient was discharged following a fifteen-day inpatient stay and remained well at six-week outpatient follow-up.

3. Discussion

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms remain a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with only twenty-two documented cases in the English literature.1,2 They develop primarily as a consequence of adventitial damage and thrombosis of the vasa vasorum, resulting in damage to the muscular and elastic components of the media and intima with ensuing extravasation of arterial blood, progressive enlargement and eventual rupture, as governed by the Law of Laplace.2–4,8 This can occur secondary to inflammatory conditions (e.g. cholecystitis, pancreatitis), malignancy, biliary tract manipulation or trauma. Formation may be further accelerated by patient factors, such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, bleeding disorders and vasculitis.1–7 Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms tend to enlarge and erode into the gallbladder and adjacent biliary tree with approximately 45% bleeding into the biliary system (haemobilia).9 The clinical presentation is that of biliary colic (70% of cases), obstructive jaundice (60%) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (100%). 32–40% of patients will present with all three symptoms – Quincke's Triad.5–7,10

In the presented case, the patient had clinical and CT-confirmed cholecystitis in the presence of fistulating gallstones. As described by Akatsu et al.11 visceral inflammation adjacent to the cystic arterial wall is likely to have produced serosal ulceration and partial erosion of the elastic and muscular components of the arterial wall, thus leading to the formation and subsequent rupture of the pseudoaneurysm. This process would be further promoted by hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes. The pathological process of cholecystitis causing pseudoaneurysm formation is very rare, as inflammation usually results in cystic artery thrombosis.3,7 Saluja et al.3 therefore discuss that pseudoaneurysm formation is likely to be due to inflammation in the presence of a large gallstone eroding into the cystic artery, as may be the cause in our case. Haemorrhage from this pseudoaneurysm into the gallbladder thus resulted in haemobilia, with subsequent biliary colic and obstructive jaundice, as highlighted by LFTs on admission. The later finding of PR blood and malaena then fulfil Quincke's triad.

Unique to this case was the synchronous presence of a cholecystojejunal fistula. Cholecystoenteric fistulas alone are a rare complication of gallstone disease, with a reported incidence of 0.15–4.8% in patients with cholelithiasis undergoing biliary surgery, of which the majority are cholecystoduodenal (71–80%).12,13 One series examined over 15,000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies and highlighted the incidence of cholecystoenteric fistulae as being 0.2% (n = 34) with only five fistulae communicating with jejunum (14.7%) – fourth most common behind fistulae to the duodenum, large bowel and stomach.14 Fistulae arise when an obstructed cystic duct become repeatedly inflamed, resulting in adhesion of the gallbladder to an adjacent viscus, in this case the jejunum, with erosion of the intervening tissues and eventual fistulation. This may be mediated by gallbladder wall necrosis from mechanical pressure due to an impacted gallstone.12 Most patients present with features of general gallstone disease but, less commonly, patients may present with cholangitis, severe upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage or gallstone ileus. In the reported case, the fistula resulted in gallstone ileus and rupture of the pseudoaneurysm produced haemobilia and upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage via the cholecystoenteric fistula. Lee et al. describes a similar presentation in a patient presenting with lower gastrointestinal bleeding as the result of a ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with a concomitant cholecystocolonic fistula.15 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this report describes the first case of a synchronous cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and cholecystojejunal fistula.

The initial investigation for a patient presenting in this manner is colour Doppler ultrasonography, which will demonstrate a pseudoaneurysm as an anechoic lesion with colour flow through it.2,3,5 This, however, has a low sensitivity and is limited when visualising sub-centimetre lesions, with one series demonstrating a detection rate of only 27%.2 Such was the case with our patient where ultrasound revealed a distended gallbladder with internal echogenicity but failed to identify the 12 mm pseudoaneurysm. An OGD was subsequently performed revealing blood in the second part of the duodenum, which was likely to be arising from the ampulla of Vater due to haemobilia. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the best means of identifying haemobilia and, if seen, limits the focus to a hepato-biliary source of the bleeding. However, endoscopy offers no means of intervention for haemobilia and, if intermittent, then this sign may be missed. Subsequent investigation is disputed in the literature between contrast-enhanced CT scanning and digital subtraction angiography. Dewachter et al. argue that contrast-enhanced CT scanning and 3-dimensional CT angiography should replace arteriography as a non-invasive method of establishing a definitive diagnosis.7 However, many sources3,5,6,8,10 state that, although invasive, selective hepatic artery angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, with a sensitivity of 80% and the ability to define aneurysms <10 mm. Diagnostic angiography can then be combined with therapeutic arterial embolisation with foam, thrombin or micro-coils, either as definitive management or as a method of haemostasis prior to cholecystectomy and aneurysm repair. There is a general consensus in the literature that emergency cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice in haemobilia due to cholecystitis, gallstones or resectable neoplasms, or if embolisation fails. Where possible, however, a two-stage approach should be adopted to managing cystic artery pseudoaneurysms: with embolisation of the bleeding pseudoaneurysm first in order to stabilise the patient followed subsequently by cholecystectomy.2–6,8,10

In our case, it was not possible to perform diagnostic angiography and so contrast-enhanced CT angiography was the investigation of choice. This not only clearly demonstrated the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm but also revealed gallstone ileus and the associated fistula. If available, arteriography and embolisation would have been appropriate to stabilise the patient but these pathologies identified on CT-imaging required urgent operative intervention and, as such, emergency laparoscopy with subsequent conversion to laparotomy was performed.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a unique case of a ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm causing haemobilia and upper gastrointestinal bleeding through a concurrent cholecystojejunal fistula. We have demonstrated the success of surgical management alone in the treatment of such a case but accept that, when available and clinically indicated, a combined therapeutic approach with angiography should be considered in the first instance.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This paper has not been presented previously as an abstract in any congress or symposium.

Contributor Information

Michael A. Glaysher, Email: michaelglaysher@me.com.

David Cruttenden-Wood, Email: dwood@doctors.org.uk.

Karoly Szentpali, Email: karoly.szentpali@hhft.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Chadha M., Ahuja C. Visceral artery aneurysms: diagnosis and percutaneous management. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26(3):196–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komatsu Y., Orita H., Sakurada M., Maekawa H., Hoppo T., Sato K. Report of a case: pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with hemobilia treated by arterial embolization. J Med Cases. 2011;2(4):178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saluja S., Ray S., Gulati M., Pal S., Sahni P., Chattopadhyay T.K. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung J.L.Y., Kan W.K. Mycotic cystic artery pseudoaneurysm successfully treated with transcatheter arterial embolization. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;16(2):156–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong J.J.R., O’Connell T., Munk P.L., Yang N., Harris A.C. Case of the month #176: pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;63:153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Molla Neto O.L., Ribeiro A.F., Saad W.A. Pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB. 2006;8:318–319. doi: 10.1080/13651820600869628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewachter L., Dewaele T., Rosseel F., Crevits I., Aerts P., De Man R. Acute cholecystitis with pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. JBR-BTR. 2012;95:136–137. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majid T.A., Ahmad R.R., Jawad A.R., Eissa A.H., Mahmmod A.S. Cystic Artery pseudoaneurysm: a rare but serious complication after cholecystectomy. Report of three cases. Postgrad Med J. 2007;6(2):164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgadillo X., Berney T., De Perrot M., Didier D., Morel P. Successful treatment of a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with microcoil embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:789–792. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sousa H.T., Amaro P., Brito J., Almeida J., Silva M.R., Romaozinho J.M. Haemobilia due to pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33(8–9):600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akatsu T., Tanabe M., Shimizu T., Handa K., Kawachi S., Aiura K. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery secondary to cholecystitis as a cause of haemobilia: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37(5):412–417. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chowbey P.K., Bandyopadhyay S.K., Sharma A., Khullar R., Soni V., Baijal M. Laparoscopic Management of Cholecystoenteric fistulas. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16(5):467–472. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W.K., Yeh C.N., Jan Y.Y. Successful laparoscopic management for cholecystoenteric fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(5):772–775. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angrisani L., Corcione F., Tartaglia A., Tricarico A., Rendano F., Vincenti R. Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is not a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(9):1038–1041. doi: 10.1007/s004640000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J.W., Kim M.Y., Kim Y.J., Suh C.H. CT of acute lower GI bleeding in chronic cholecystitis: concomitant pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery and cholecystocolonic fistula. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(7):634–636. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]