Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Biliary inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) represent an exceptional benign cause of obstructive jaundice. These lesions are often mistaken for cholangiocarcinomas and are treated with major resections, because their final diagnosis can be achieved only after formal pathological examination of the resected specimen. Consequently, biliary IPTs are usually managed with unnecessary major resections.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 71-year-old female patient underwent an extra-hepatic bile duct resection en-bloc with the gallbladder and regional lymph nodes for an obstructing intraluminal growing tumor of the mid common bile duct (CBD). Limited resection was decided intraoperatively because of negative for malignancy fast frozen sections analysis in addition to the benign macroscopic features of the lesion. Histologically the tumor proved an IPT, arising from the bile duct epithelium, composed of inflammatory cells and reactive mesenchymal tissues.

DISCUSSION

The present case underlines the value of intraoperative reassessment of patients undergoing surgical resection for histopathologically undiagnosed biliary occupying lesions, in order to optimize their surgical management.

CONCLUSION

The probability of benign lesions mimicking cholangiocarcinoma should always be considered to avoid unnecessary major surgical resections, especially in fragile and/or elderly patients.

Keywords: Inflammatory pseudotumor, Extrahepetic bile ducts, Cholangiocarcinoma, Benign biliary occupying lesions

1. Introduction

Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) of the biliary ducts represent an exceptional benign cause of painless obstructive jaundice. These masses are often mistaken for cholangiocarcinomas and are treated with major resections, because their final diagnosis can usually be achieved only after formal pathological examination.1 The present report describes the clinical findings, work-up, surgical treatment and pathology findings of a 71-year-old Greek woman, who presented with painless obstructive jaundice, because of an obstructing intraluminal growing mass of the mid common bile duct (CBD). The patient underwent an extra-hepatic bile duct resection instead of a more extended procedure because of negative fast frozen sections analysis in addition to the benign intraoperative macroscopic features of the lesion. Final diagnosis was consistent with a benign endoluminal growing mid CBD IPT. Additional interesting findings were that the tumor was arising from a macroscopically smooth bile duct epithelium and was pedunculated, having a polypoid-like appearance with smooth surface, protruding freely into the CBD lumen.

The present case is interesting not only because of the rarity and the unique macroscopic features of the lesion but also because it underlines the importance of intraoperative reassessment of patients undergoing surgical resection for undiagnosed biliary occupying lesions.

2. Case report

A 70-year-old female patient with an unremarkable past medical history was admitted to our Department with a recent history of painless obstructive jaundice, post-prandial low back pain, anorexia and weight loss (4 kg over the last 2 months). Physical examination revealed mild obesity, scleral icterus and pruritus. No acute distress was noted, and there were no clinical signs of abdominal mass except from a tense palpable painless gallbladder. Her liver, spleen and superficial lymph nodes were not enlarged. Laboratory analysis at the time of referral showed normal white blood cell count, C-reactive protein 2.5 mg/dl (normal range: 0–10 mg/dl) and serum pancreatic amylase level 38 U/l (normal range: 23–90 U/L). Serum direct bilirubin (14.9 mg/dl, normal range: 0–0.3 mg/dl), aspartate (70 IU/l, normal range: 10–36 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferases (64 IU/l, normal range: 7–35 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (610 IU/l, normal range: 44–147 IU/L), and γ-glutamyltransferase (256 IU/l, normal range: 0–51 IU/L) levels were markedly elevated. Serum levels of CEA and Ca 19–9 in addition to hepatitis viral tests were normal.

Transabdominal ultrasonography revealed dilatation of the intra and extrahepatic biliary tree, proximal to the level of the mid-distal CBD, while no stones were depicted in the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Subsequent magnetic resonance tomography of the abdomen combined with magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) revealed the presence of an obstructing mass in the mid-distal common bile duct with uninvolved intrahepatic biliary ducts and intrapancreatic part of the CBD. Portal and hepatic arterial systems were normal and there were no signs of metastatic disease.

Subsequently, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was followed in an attempt to establish a more accurate diagnosis and jaundice relief. ERCP revealed the presence of an obstructing mass in the mid CBD with no other abnormalities in the intrahepatic biliary system. Attempts for biopsy samples and stent deployment across the mass were unsuccessful. Based on the results of preoperative work-up the patient was considered for surgical exploration for a biliary occupying lesion highly suspicious for cholangiocarcinoma.

At surgery, thorough peritoneal inspection revealed no metastatic disease. The CBD appeared dilated proximal to a palpable firmed mass about the size of a hazelnut, located in its mid-distal portion. A diffuse and irregular fibrosing lesion was surrounding the mass, involving the adjacent lymph nodes and the underlining portal vein. Regional lymph nodes were completely excised. The extrahepatic bile ducts and gallbladder were mobilized superiorly up to the level of the hepatic hilum, exposing the hilar structures, which were free of disease. The hilar plate was lowered and the proximal duct was transected at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts.

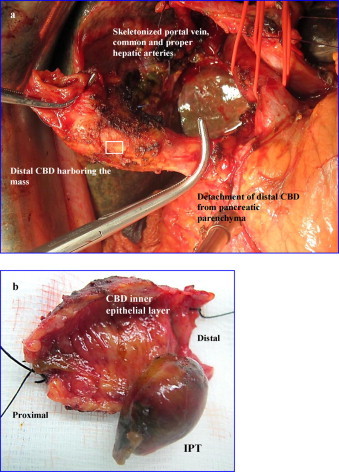

An extended Lane-Kocher maneuver was then performed and the retroduodenal segment of the CBD was copiously and meticulously separated from the portal vein. To achieve a free distal resection margin the dissection was advanced more distally by detaching the bile duct from the pancreatic tissue (Fig. 1a). The mobilized distal CBD was then isolated and divided. The retropancreatic lymph nodes were resected en bloc.

Fig. 1.

(a) Intraoperative photograph. After lowering the hilar plate the hepatic duct was transected at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts. Following this, an extended Lane-Kocher maneuver was performed to allow the dissection of the distal bile duct up to the level of the head of the pancreas. As depicted in the photograph the retroduodenal segment of the CBD was meticulously separated from the portal vein. The dissection was advanced more distally by detaching the CBD from the pancreatic tissue to achieve a free distal resection margin. (b) Resected specimen opened (box in (a)). After opening the duct, a 3 cm in diameter pedunculated polypoid mass, being well-demarcated with smooth surface protruding freely into the CBD lumen was evident. These gross features were indicative for the benignity of the lesion.

Negative for malignancy fast frozen sections microscopic analysis of the proximal and distal resection margins of the extrahepatic biliary tract, and regional lymph nodes in addition to the macroscopic appearance of the mass (Fig. 1b) were indicative for the benignity of the lesion. Based on these findings it was decided to perform a limited resection in the form of extra-hepatic bile duct excision en-bloc with the gallbladder and regional lymph nodes.

The biliary-enteric continuity was restored with a challenging terminolateral retrogastric, retrocolic Roux-en-Y biliojejunal anastomosis because of a triple hepatic duct confluence (trifurcation) variation at the porta hepatis. The postoperative course was uneventful and serum bilirubin levels normalized on the 10th postoperative day.

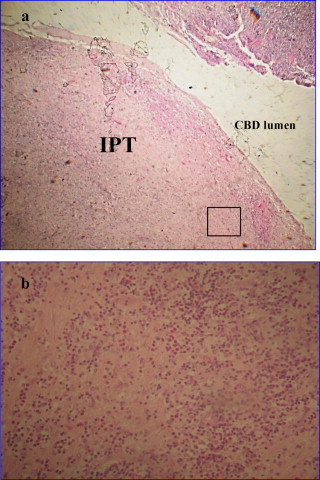

Final histopathologic examination of the surgical specimen revealed an inflammatory pseudotumor adjacent to the common bile duct inner epithelial layer. The latter exhibited reactive inflammatory changes without atypia or dysplasia and there was no evidence of duct fibrosis consistent with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Macroscopically the lesion was 3 cm in diameter and had a pedunculated polypoid-like appearance, being well-demarcated with smooth surface, protruding freely into the CBD lumen (Fig. 2a). The lesion had a gray-white cut surface. Microscopically the lesion was composed of fibrous stroma with dense inflammatory cell infiltrate and reactive mesenchymal tissue, while the connective tissue stroma of the distal CBD exhibited a severe mixed inflammatory infiltrate also (Fig. 2b). Resected regional nodes were enlarged and congested but without scleroses, while their surrounding adipose tissue was largely replaced by cellular inflammation rich in plasma cells and lymphocytes.

Fig. 2.

(a) Enlargement of the macroscopic appearance of the inflammatory pseudotumor located in the distal common bile duct: a well demarcated polypoid-like lesion, with smooth surface protruding into the CBD lumen (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, original magnification 20×). (b) Photomicrograph showing the microscopic features of the IPT (box in (a)): the lesion is composed of fibrous stroma with dense, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils and plasmocytes (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, original magnification 100×).

Following final histopathological diagnosis, the patient was checked for Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) infection and autoimmunogenic processes, however, EBV IgM/IgG and IgG4 serum antibodies were not detected. At 8 months from operation, the patient is doing well and there is no clinical, biochemical or radiological evidence of recurrent disease.

3. Discussion

Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) are rare, idiopathic, benign, mass lesions composed of fibrous tissue with marked nonspecific inflammatory infiltrate, mainly consisting of spindle cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages.2 They can practically develop in every conceivable site in the body, however; the most common locations are lungs, omentum and mesentery.3 There are many reports of IPTs of the extrahepatic biliary tree but in only 7 previous cases was the CBD identified as the location of the tumor (Table 1).4–10

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with IPT of the CBD reported in the English language literature (CBD, common bile duct; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy).

| Authors/publication year | Age at diagnosis/sex | Size (cm) | Location/extension | Surgical management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haith et al./1964 | 6/M | 3 in diameter | Distal CBD | PD |

| Stamatakis et al./1979 | 13/F | 3 in diameter | Proximal CBD/cystic duct and common hepatic duct | Extrahepatic bile duct resection |

| Ikeda et al./1990 | 43/M | No mass lesion-diffuse infiltration | Proximal CBD/intrahepatic ducts, common hepatic duct, gall bladder and lymph nodes | Cholecystectomy |

| Fukushima et al./1997 | 58/F | 1.7 × 1.0 × 1.0 cm | Mid CBD/pancreas and lymph nodes | PD |

| Walsh et al./1998 | 69/F | 7 in diameter | Proximal CBD | PD |

| Sobesky et al./2003 | 51/F | 1.5 in diameter | Distal CBD | PD |

| Abu-Wasel et al./2012 | 55/M | No mass lesion-diffuse infiltration | CBD/common hepatic duct | Right extended hepatic and extrahepatic bile duct resection |

| Present case/2013 | 71/F | 3 in diameter | Mid CBD | Extrahepatic bile duct resection |

The etiology of IPTs remains unsettled. Among the various proposed physiopathological hypotheses, the most likely is antecedent bacterial, parasitic, or viral infections. Indeed, there is a well-established association between Epstein–Barr virus infection and IPT development, since Epstein–Barr virus has often been found in histopathological IPT samples.11–13 Furthermore, some authors claim that hepatobiliary IPTs develop as a result of recurrent episodes of acute cholangitis, secondary to portal venous infection and obliterating phlebitis.14,15 Nevertheless, the exact role of various infectious agents in the pathogenesis of IPTs is not completely clarified.16 Another proposed underlying etiology for the development of IPTs is autoimmunogenic processes, since some cases have responded well to corticosteroid treatment.17 The latter etiology is further supported by the fact that IgG4-related IPTs of the liver developed in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis.18,19

Painless obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain and fever are the most common clinical findings in patients with biliary IPTs. Their clinical presentation and imaging features are non-specific and are indistinguishable from those of cholangiocarcinoma, making their preoperative diagnosis extremely difficult.20 Additionally, preoperative tumor sampling is technically challenging and if usually results in suboptimal diagnosis.10 Notwithstanding, distinction between IPTs and malignant lesions is crucial, because IPTs have a benign biological behavior and are characterized by the property of spontaneous regression.21 Unfortunately, so far there is no preoperative investigative modality available to definitively rule out malignancy and decide on the indication and extent of surgical resection. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the majority of reported biliary IPTs, the lesion was initially considered as cholangiocarcinoma and was treated with major surgical resections. In the present case, although the tumor was initially mistaken for cholangiocarcinoma, a limited resection was finally decided because of the benign intraoperative features of the lesion and negative margin shown by fast frozen section analysis.

The histopathological characteristics of IPTs include a non-specific inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of spindle cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages, and collagen tissue composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Necrosis and occlusive phlebitis may also be observed suggesting infectious and vascular factors respectively.2,16 The present case is very unusual in terms of macroscopic features and location. Furthermore, the coexistent lymphadenopathy identified intraoperatively and confirmed on histopathological examination is also rare and corresponds evidently to reactive lymphadenitis secondary to the primary inflammatory lesion. Surgical resection of biliary tract IPTs represents the treatment of choice ensuring a satisfactory prognosis. Bypass operations such as hepaticojejunostomy are also indicated provided that the tumor has been proved clearly benign.

In conclusion, although biliary IBTs are extremely rare, this case should alert hepatopancreatobiliary surgeons to be aware of such a rare benign entity. The probability of benign lesions mimicking cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing surgical exploration for histopathologically undiagnosed biliary occupying lesions should always be considered to avoid unnecessary major resections, especially in fragile or elderly patients. Although surgical exeresis of a presumed bile duct cancer represents a generally accepted surgical option, however; the extent of resection should be determined by the intraoperative findings and fast frozen sections analysis.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Oral approval was obtained from the General Hospital Papageorgiou and informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author contributions

Vasiliadis K.: study design, data collections, data analysis, performed the operation, writing.

Fortounis K.: study design, data collections, third operator.

Papavasiliou C.: second operator, data collections.

Kokarhidas A.: study design, data collections, data analysis.

Al Nimer A.: study design, data collections, data analysis.

Fachiridis D.: study design, data collections, data analysis.

Pervana S.: histopathological examination, data analysis.

Makridis C.: study design, approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Blumgart L.H., Beazley R.M. Benign tumours and pseudotumours of the biliary tract. In: Blumgart L.H., editor. vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1998. pp. 819–828. (Surgery of the liver and biliary tract). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin C.M., Watterson J., Priest J.R., Dehner L.P. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffin C.M., Humphrey P.A., Dehner L.P. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haith E.E., Kepes J.J., Holder T.M. Inflammatory pseudotumor involving the common bile duct of a six-year-old boy: successful pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1964;56:436–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamatakis J.D., Howard E.R., Williams R. Benign inflammatory tumour of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 1979;66:257–258. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800660412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda H., Oka T., Imafuku I., Yamada S., Yamada H., Fujiwara K. A case of inflammatory pseudotumor of the gallbladder and bile duct. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukushima N., Suzuki M., Abe T., Fukayama M. A case of inflammatory pseudotumour of the common bile duct. Virchows Arch. 1997;431:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s004280050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh S.V., Evangelista F., Khettry U. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreaticobiliary region: morphologic and immunocytochemical study of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:412–418. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobesky R., Chollet J.M., Prat F., Karkouche B., Pelletier G., Fritsch J. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 2003;35:698–700. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Wasel B., Eltawil K.M., Molinari M. Benign inflammatory pseudotumour mimicking extrahepatic bile duct cholangiocarcinoma in an adult man presenting with painless obstructive jaundice. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012(June):006514. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oz Puyan F., Bilgi S., Unlu E., Yalcin O., Altaner S., Demir M. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen with EBV positivity: report of a case. Eur J Haematol. 2004;72:285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.0902-4441.2003.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arber D.A., Weiss L.M., Chang K.L. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus in inflammatory pseudotumor. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis J.T., Gaffney R.L., Casey M.B., Farrell M.A., Morice W.G., Macon W.R. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen associated with a clonal Epstein–Barr virus genome. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:56–61. doi: 10.1309/BUWN-MG5R-V4D0-9YYH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon K.H., Ha H.K., Lee J.S., Suh J.H., Kim M.H., Kim P.N. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: CT–histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1999;211:373–379. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma36373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Someren A. Inflammatory pseudotumor of liver with occlusive phlebitis: report of a case in a child and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:176–181. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupovitch A., Chen R., Mishra S. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Report of the fine needle aspiration cytologic findings in a case initially misdiagnosed as malignant. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonaka D., Birbe R., Rosai J. So-called inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour: a proliferative lesion of fibroblastic reticulum cells? Histopathology. 2005;46:604–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanno A., Satoh K., Kimura K., Masamune A., Asakura T., Unno M. Autoimmune pancreatitis with hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor. Pancreas. 2005;31:420–423. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000179732.46210.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchida K., Satoi S., Miyoshi H., Hachimine D., Ikeura T., Shimatani M. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the pancreas and liver with infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells. Intern Med. 2007;46:1409–1412. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tublin M.E., Moser A.J., Marsh J.W., Gamblin T.C. Biliary inflammatory pseudotumor: imaging features in seven patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W44–W48. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koide H., Sato K., Fukusato T., Kashiwabara K., Sunaga N., Tsuchiya T. Spontaneous regression of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with primary biliary cirrhosis: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1645–1648. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i10.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]