Abstract

Virus capsid assembly has been widely studied as a biophysical system, both for its biological and medical significance and as an important model for complex self-assembly processes. No current technology can monitor assembly in detail and what information we have on assembly kinetics comes exclusively from in vitro studies. There are many differences between the intracellular environment and that of an in vitro assembly assay, however, that might be expected to alter assembly pathways. Here, we explore one specific feature characteristic of the intracellular environment and known to have large effects on macromolecular assembly processes: molecular crowding. We combine prior particle simulation methods for estimating crowding effects with coarse-grained stochastic models of capsid assembly, using the crowding models to adjust kinetics of capsid simulations to examine possible effects of crowding on assembly pathways. Simulations suggest a striking difference depending on whether or not a system uses nucleation-limited assembly, with crowding tending to promote off-pathway growth in a nonnucleation-limited model but often enhancing assembly efficiency at high crowding levels even while impeding it at lower crowding levels in a nucleation-limited model. These models may help us understand how complicated assembly systems may have evolved to function with high efficiency and fidelity in the densely crowded environment of the cell.

Introduction

Virus capsid assembly has proven to be a powerful model system for understanding highly complex macromolecular assembly in general. Nonetheless, many features of the capsid assembly process, such as detailed binding kinetics and pathways, remain inaccessible to direct experimental observation. Given the limited sources of experimental data, theory and computational simulation methods have played essential roles in developing detailed functional models of capsid assembly. Simulation approaches have proven very effective, for example, at exploring ranges of possible parameters, identifying those that lead to productive assembly, and examining the pathways they imply (1–18). The majority of these simulation approaches can roughly be classified into either ordinary differential equation models (1–6), molecular dynamics-like particle models (7–11) or some variant such as Langevin dynamics (12), or continuum mechanical models (13,14). This work has, however, been largely restricted to working with either highly simplified models with small numbers of parameters (1–11) or to generic models of capsid assembly in the abstract through which one can explore ranges of possible behaviors (13–15). Although models of virus capsid assembly have become far more complex in recent years (16–18), until recently they provided no way to create detailed quantitative models of the kinetics of subunit addition for real viruses.

In prior work, we developed an approach to address the problem of learning detailed quantitative models of capsid assembly kinetics for specific viruses by combining fast discrete event stochastic simulations of capsid assembly from generic rule models (19–21) with numerical optimization algorithms to fit specific rate constants to experimental light scattering data (22,23). By tuning parameters to optimize fit of simulated and true light scattering data, this work made it possible for the first time, to our knowledge, to learn detailed kinetic models tuned to describe assembly of specific virus capsids. Applying the method to three icosahedral viruses—cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV)—yielded a set of kinetic pathway models revealing some common features between systems but also a surprising diversity of behaviors across the systems.

Learning detailed kinetic models to fit in vitro assembly data is, however, only one step toward understanding the natural assembly mechanisms of these or other viruses. Even a perfectly faithful model of assembly in vitro may yield limited insight into the natural assembly of the virus because the in vitro assembly environment itself is quite different from the environment of a living cell in which a virus would normally assemble. In principle, computational methods provide a way to bridge this gap as well, by allowing us to learn interaction parameters of assembly proteins from the in vitro system then observe how their behavior changes when transferred to a more faithful computational model of the environment in vivo. Accurately representing the in vivo intracellular environment is not a simple task, though, as it differs from the test tube in numerous ways, many still imperfectly understood. Furthermore, we have no clear understanding of which of these differences are actually relevant to assembly kinetics and pathways. For example, the presence of nucleic acid inside the viral capsid at the time of assembly can make a large difference in the thermodynamics of the assembly environment, beyond the potential direct interactions that may also aid in the assembly process (24–26). The presence of chaperone proteins or other intracellular machinery can also play a large role in either promoting or inhibiting the ability of a virus to form (27,28). The extreme complexity of the true system and the uncertainty regarding which factors actually affect assembly pathways suggests the prudence of a bottom-up approach: studying individual factors of interest and determining whether they are likely to, singly or in combination, substantially alter assembly mechanisms.

In this work, we take one step toward answering the question of how capsid assembly pathways may differ in vitro versus in vivo by focusing on a single factor, macromolecular crowding, that sharply distinguishes intracellular from typical in vitro systems and that is well known to influence kinetics and thermodynamics of numerous macromolecular assembly processes (29–32). Predicting the effects of nonspecific crowding on any particular system is extremely difficult, because crowding can both inhibit growth, by slowing diffusion and impeding binding, or promote growth, by providing an entropic benefit to coalescing into more compact assembled forms due to excluded volume effects. There is clear evidence from experiments (33,34) and computational modeling (15,36,37) for an important role for crowding in capsid assembly, although the effects of crowding on complex pathway selection is not characterized in sufficient detail to explore how assembly pathways of any particular virus may be affected by intracellular levels of crowding. Different computational approaches have been taken to address the effects of crowding with some groups favoring highly detailed crowding models of ensembles of cellular crowders to avoid omitting possibly relevant factors (36,37), whereas others favor incorporating the minimal detail necessary to yield observed crowding behavior and argue that simple models can accurately mimic effects of far more complicated ensembles expected in nature (38). Although the latter work does not tell us the precise parameters a simple uniform-crowder model should have to accurately mimic a cell-like ensemble of distinct crowders, it does suggest that scanning a range of possible total crowding levels in a simple uniform model can stand in well for a much higher dimensional search of possible combinations of crowder sizes and concentrations that might be present in any actual system. Because of the size and complexity of the model systems we study, we have favored the minimalist approach of starting from a simple model and incorporating only complexity shown to be most relevant to quantifying the effect of macromolecular crowding on assembly reactions. To this end, we combine two separate prior modeling approaches—one for simulating capsid assembly and one for simulating the effects of macromolecular crowding on simple assembly reactions—to explore ranges of possible crowding effects on model capsid assembly systems. To achieve the high efficiency needed to model large numbers of trajectories for systems with often very slow rate-limiting nucleation reactions, we rely on our prior stochastic simulation models of capsid assembly (19–21), trained to fit light scattering data on real in vitro capsid assembly systems (22,23). To model crowding without compromising runtime, we extend an approach using test reactions run in a comparatively slow space-aware diffusion model (39) to train regression models one can use to estimate crowding effects on kinetics of a wide range of parameter values (40). To deal with uncertainty in the total crowding level likely to be encountered by any real viral system, we apply this model across a broad range of total crowding levels, from 0% to 45% total excluded volume. The result is a dual-scale simulation that offers the efficiency of our prior rule-based models, needed for detailed pathway analysis, combined with physical representations of a simple particle model of macromolecular crowding. We use these tools to project possible effects of increased crowding on three virus systems analyzed in our prior work: CCMV, HPV, and HBV. The remainder of this work describes our computational approach in greater detail, reports apparent effects of increasing levels of computationally simulated crowding on each system, and uses these results to draw some conclusions about how crowding may influence these specific viruses or viral assembly generically.

Materials and Methods

Capsid simulation method

We have previously developed a rules-based discrete event stochastic simulator called Discrete Event Simulator of Self-Assembly (DESSA) (21) to model the process of capsid assembly from individual subunit building blocks through individual association and dissociation events into completed capsids. Simulated assembly is governed by simple biochemical rule sets specifying the geometries of the subunits, three-dimensional positioning of binding sites, and the specificities and on- and off-rates of binding events between binding sites. DESSA samples among all possible bond formation (association) and breaking (dissociation) events at each step in the simulation using a variant of the stochastic simulation algorithm (41,42). More details of the DESSA simulator and its application here are provided in the Supporting Material under Discrete Event Simulation of Capsid Assembly. In the viral systems we study, the individual subunits can represent either individual coat proteins or small stable oligomers of coat proteins. In the case of HPV, the subunit corresponds to a pentamer of HPV capsid proteins, which experimental evidence has shown to be the basic unit of assembly (43,44). For CCMV and HBV, we use dimers of coat proteins as the individual subunits, as the experimental data also involved in vitro assembly from coat dimers (45–48). We assumed kinetic rates in the uncrowded case to be those we derived from a previous study of these viruses using a numerical optimization scheme to fit parameters to minimize the root mean-square deviation between in vitro experimental static light scattering data and light scattering curves generated based upon our DESSA simulation output (23). This parameter estimation method is described in more detail in the Supporting Material under Parameter Estimation from in vitro Data.

Modeling the crowding effect

To simulate potential effects of crowding on capsid assembly, we use a strategy we previously developed to quickly estimate corrections to equilibrium constants to account for crowding in complex assembly models. This method was intended to address the problem that simplified stochastic models used in our large-scale assembly simulations cannot model crowding effects, although the more realistic explicit particle models that can represent crowding are too slow to handle the large numbers of particles and simulation trajectories required for our studies. The method first uses off-lattice particle models implemented with Green’s function reaction dynamics (49) to test effects of varying levels of a homogeneous nonspecific crowding agent on a generic homodimerization test system for a range of model parameters (39). It then trains a regression model to predict Keq values as functions of the parameters. Additional test simulations are used to derive corrections to diffusion rate and thus corrections to forward rates of binding (k+) under a model of diffusion-limited binding for each crowding level. The combination of the regression model of Keq and the corrections to k+ provide a fast surrogate to allow us to adjust kinetic rates at each binding site and crowding level to provide a model of altered binding kinetics in the presence of crowding. These corrected rates are then fed into the DESSA simulator to provide self-assembly simulations intended to reflect altered kinetics due to molecular crowding. The overall method is discussed in more detail in the Supporting Material under Molecular Crowding Simulation and Regression Model of Crowding Effects.

Simulation experiments

For each virus, we produced crowding-corrected parameter files for crowding agent levels from 0% to 45% in increments of 5%, with rate parameters determined relative to the best-fit in vitro parameters for all three viruses, presumed to represent 0% nonspecific molecular crowding. We then ran 100 simulation trajectories for each virus at each crowding level, to allow for adequate sampling given the stochasticity of our simulator. For each simulation, we followed the same protocols as our previous work (23). For HBV and CCMV, each simulation was begun using enough initial free subunits to generate five complete capsids per simulation: 450 subunits for CCMV and 600 subunits for HBV. For HPV, to ensure in the 0% crowding agent case a greater likelihood of producing at least one completed capsid, each simulation was begun using enough subunits to generate 10 complete capsids per simulation: 720 subunits total. Each simulation ends when all capsids have been formed, there are no events left in the simulation queue, or a predetermined simulation time limit empirically determined to allow simulations to go to pseudoequilibrium is reached. For these simulations, the time limit for CCMV and HBV was set to 1000 s, whereas the time limit for HPV was set to 150,000 s because of the far greater time required to assemble an HPV capsid in vitro and in silico.

We then analyzed the trajectories to derive summaries of assembly pathways in the form of tables of frequencies of possible binding interactions and time series of mass fractions of different sizes of species versus time for each trajectory. Such indirect measures of pathways are necessary because the true number of pathways will generally be exponentially large in the size of the structure to be assembled. To construct the binding frequency tables, we count all association events that occur across all repetitions of each simulation input and produce a matrix with one row or column for each subunit contained in a completed capsid. We place in position (i, j) the count of all bond-forming events involving an assembly of j subunits producing an assembly of i subunits. We then scale each row by the total number of association events involving the production of an assembly of i subunits, so that each position in the matrix contains a frequency between 0 and 1. To construct mass fraction plots, we record after each 100 simulation events the quantity of each assembly size (from monomer to complete capsid) currently present in the simulator. We then scale each of these assembly size counts by the number of subunits present in the assembly (e.g., a pentamer is scaled by five as the mass of a pentamer in each simulation would be five times that of a monomer). We finally normalize each value such that it represents the frequency, between 0 and 1, instead of the total count of subunits in each assembly size. We plot this value versus simulation time for each potential assembly size. We further develop aggregate measures of assembly kinetics based on the average time required over a set of trajectories to reach 50% or 67% completion of potential capsids.

Results and Discussion

Estimating crowding corrections for capsid coat binding reactions

Table 1 shows relative crowding corrections for equilibrium and rate constants for each virus at crowding levels from 0% to 45%. By crowding level, we refer throughout the results to the percentage of nonspecific crowding (0% and 45%) rather than the total crowding to avoid confusion due to the slight differences in volume contributed by the viral assembly subunits themselves. True total crowding levels will be between one and three-hundredths of a percent higher than these stated crowding levels, depending upon the virus. The table shows a general trend toward increased Keq with an increasing crowding level, concurrent with simultaneous decreases in both k+ and k- with increasing crowding. This effect is similar to that observed in prior uses of these crowding models (39,40). The corrections in Table 1 provide scaling factors needed to adjust our previous in vitro best-fit kinetic rates (23) to more accurately model increasing crowding levels for each virus. Table S1 in the Supporting Material lists the corrected kinetic on- and off-rates for each virus binding reaction at each crowding level.

Table 1.

Crowding-corrections for equilibrium constants, on-rates, and off-rates for HPV, CCMV, and HBV generated by the GFRD simulator and regression model

| Crowding level | 0% | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% | 35% | 40% | 45% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV | 1 | 1.26 | 1.39 | 1.54 | 1.87 | 2.54 | 3.88 | 6.46 | 11.9 | 26.8 | |

| k+ (10−16 mol-1m3s−1) | 1 | .683 | .474 | .340 | .252 | .193 | .147 | .106 | .069 | .041 | |

| k- (10−8 ms−1) | 1 | .543 | .341 | .221 | .135 | .076 | .038 | .016 | .006 | .002 | |

| CCMV | 1 | 1.32 | 1.45 | 1.65 | 1.96 | 2.68 | 4.04 | 6.60 | 12.0 | 27.1 | |

| k+ (10−16 mol-1m3s−1) | 1 | .683 | .474 | .340 | .252 | .193 | .147 | .106 | .069 | .041 | |

| k- (10−8 ms−1) | 1 | .517 | .326 | .206 | .128 | .072 | .036 | .016 | .006 | .002 | |

| HBV | 1 | 1.34 | 1.47 | 1.69 | 1.98 | 2.71 | 4.06 | 6.63 | 12.0 | 27.1 | |

| k+ (10−16 mol-1m3s−1) | 1 | .683 | .474 | .340 | .252 | .193 | .147 | .106 | .069 | .041 | |

| k- (10−8 ms−1) | 1 | .508 | .322 | .201 | .127 | .071 | .036 | .016 | .006 | .002 |

The corrections calculated here are applied to the best-fit in vitro parameters of our capsid assembly simulator to reflect increasingly crowded assembly conditions.

Effects of crowding on bulk kinetics of simulated assembly

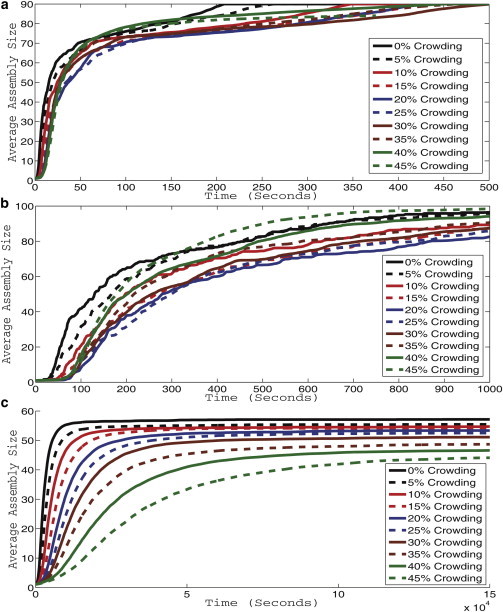

We next ran replicates of assembly simulations for each of the three viruses and 10 crowding levels. Fig. 1 shows simulated light scattering curves for CCMV, HBV, and HPV at each crowding concentration, averaged over 100 trajectories per crowding level.

Figure 1.

Simulated light scattering curves for CCMV (a), HBV (b), and HPV (c). Each curve represents an average simulated light scattering over 100 simulation trajectories. Curves are shown for levels of nonspecific crowding agents from 0% to 45% of simulation solution volume in increments of 5%.

Fig. 1 a shows results for CCMV. At low crowding levels, the figure shows a pattern of decreasing speed and yield of assembly, with the assembly rate reaching a minimum at 25% crowding. The effect reverses at higher crowding levels, with the assembly rate at 35% crowding approaching that of the uncrowded system, and with 40% and 45% crowding yielding faster assembly at intermediate time points of the simulation. All trajectories go to equivalent levels of completion eventually, although with varying kinetics.

Fig. 1 b shows curves for HBV, which show qualitatively similar behavior to those for CCMV. HBV also shows a pattern of decreasing speed and quantity of assembly at low crowding levels, again reaching a minimum at 25% crowding, but increased assembly with respect to both speed and yield as crowding levels continue to increase. Crowding levels above 30% begin to approach the assembly rate of the 0% crowding state. 45% crowding yields higher assembly rates than 0% crowding levels in the later stages of assembly. HBV yields a higher apparent variance in the final yield of completed capsids than does CCMV. With HBV, assembly yield initially drops along with assembly rate as crowding is introduced, with yields at 10–35% crowding well below those of the uncrowded case. Yield approaches that of the uncrowded system by 40% crowding and surpasses it at 45% crowding.

Fig. 1 c shows curves for HPV, which show strikingly different behavior than the CCMV or HBV simulations. HPV shows a monotonic decrease in both rate and yield of assembly with increasing crowding rates. The curves also show a much lower variance than did the HBV or CCMV curves, with the effects of increasing crowding clearly distinguishable from the noise in the individual averaged simulated light scattering curves.

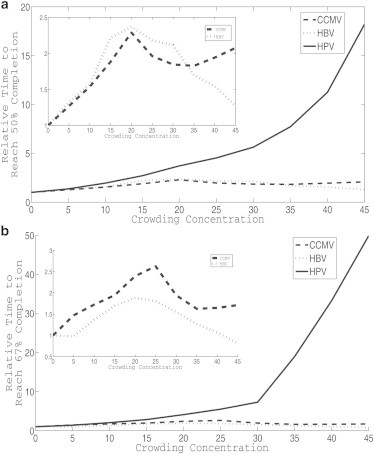

We next chose to look in greater detail at the kinetic effects of crowding on the different viruses’ assemblies by comparing the average time required for each virus to reach 50% completion and 67% completion of the capsids in simulation. These measures are used to bypass a problem of mass averaging across assembly sizes in light scattering curves, namely that it tends to conflate productive assembly leading to complete capsids with unproductive off-pathway assembly leading to kinetically trapped intermediates. Fig. 2 plots these times to partial completion for all crowding levels examined for the three viruses. Fig. 2, a and b, show a dramatic difference again between how the HPV model reacts to increased crowding compared to the CCMV and HBV models, with the CCMV and HBV times largely stable across crowding levels but the HPV times increasing greatly with higher crowding. Because the large change in HPV times makes it difficult to appreciate variations in CCMV or HBV times on a common scale, we add insets to the figures showing results solely for CCMV and HBV. The insets show an increase in time required for both viruses at low crowding levels, peaking between 20% and 25% crowding. Both viruses show about a 125% increase in time to 50% completion and a 75% increase for HBV in time and a 150% increase for CCMV in time to 67% completion. At higher crowding levels, CCMV shows a reduction in relative time to a local minimum at 35% crowding for both the 50% (a) and 67% (b) completion graphs. The average times then slightly increase again at the highest crowding levels. The highest crowding levels for CCMV are slower to reach 50% and 67% completion than the 0% level, although the higher levels eventually yield faster kinetics to reach 80% completion. For HBV, there is no local minimum at 35% as the relative time decreases at all crowding levels above 20%. 45% crowding approaches the 0% crowding case in 50% completion time (Fig. 2 a) and there is a reduction in relative time for the highest crowding level for the 67% completion time (Fig. 2 b). The figure implies that crowding acts earlier in HBV than CCMV assembly to accelerate the process.

Figure 2.

Average times required to reach 50% (a) and 67% (b) completed capsids for HPV, HBV, and CCMV models. All graphs are scaled to yield a starting time of 1 at 0% crowding. Subsequent crowding levels show the multiple of that initial time required to reach a given level of completion at a given crowding level. The inset in each figure represents a graph of just HBV and CCMV to highlight variations that are obscured by the large change in HPV completion times as a function of crowding level.

Crowding effects on individual assembly trajectories

We next examined individual assembly trajectories to gain insight into the mechanisms by which crowding enhances bulk assembly of the HBV and CCMV models and suppresses bulk assembly of the HPV model. To this end, we produced plots of mass fractions of each assembly size over time for each virus at each crowding level. Although space would not allow us to show such figures for all simulation trajectories, we provide an illustrative sample in Fig. 3. Fig. 3, a, d, and g, show mass fraction plots for the three viruses with negligible crowding. The short peaks present in the HBV and CCMV plots (Fig. 3, a and d), correspond to nucleation events followed by the rapid production of finished capsids, a feature absent from the HPV plot (Fig. 3 g). Both HBV and CCMV also maintain pools of trimers-of-dimers, which we previously found in uncrowded simulations to be an important participant in the assembly pathways for these viruses (23). No large pools of assemblies are consistently present for either HBV or CCMV, aside from monomers, complete capsids, and this trimer-of-dimers intermediate. HPV, by contrast, shows a growing pool of partially assembled structures of varying sizes that form and then persist throughout the simulation. This latter pattern is indicative of kinetic trapping, in which many partial capsids form simultaneously and deplete free monomers to such a degree, that none can assemble to completion. This kinetic trapping has been previously observed in many capsid assembly models (5,6,21,23,50–53).

Figure 3.

Mass fraction plots for CCMV at crowding levels of 0% (a), 20% (b), and 40% (c), HBV at crowding levels 0% (d), 20% (e), and 40% (f), and HPV at crowding levels of 0% (g), 20% (h), and 40% (i). Each plot shows a mass fraction for each size of intermediate versus time. The large number of intermediates makes it impractical to provide a full color key and necessitates repeating colors; however, the most frequently observed intermediates are colored as follows: Monomers are blue, trimers are red, and pentamers are purple. The plateauing yellow line for CCMV and blue line for HBV represent completed capsids.

In Fig. 3, b, e, and h, we examine the changes in individual simulation trajectories induced by moderate (20%) crowding levels. Fig. 3 b, a trajectory of CCMV with 20% crowding, shows a qualitatively similar picture to that of CCMV without crowding: a growth process with clearly defined nucleation events each touching off growth of a single capsid. Quantitatively, however, the process is slowed in both the nucleation and growth phases. Nucleation events are more widely spaced and the peaks corresponding to growth after nucleation are noticeably widened relative to the uncrowded case. The introduction of crowding also seems to produce a visible pool of 10-mers of dimers only evident for brief time periods in the uncrowded case; subsequent analysis showed this pool to be present for the majority of simulation runs at crowding levels between 10% and 25%. For levels lower than 10% and above 25%, 10-mers of dimers are still produced, although they are then added to larger assemblies at fast enough rates that no consistent pools are formed, except toward the end of simulation runs when assembly slows down due to fewer unbound capsid proteins available to take part in assembly reactions. Fig. 3 e shows that, for HBV, 20% crowding yields similar appearances for individual trajectories save for an increase in time to assemble and a lower likelihood of completing as many capsids by the end of the simulation time. There is no pool of 10 mers-of-dimers at 20% crowding for HBV, unlike CCMV. Fig. 3 h shows a highly distinct effect of simulated crowding on the HPV model. Kinetic trapping is visible both with and without crowding, with simulated capsomers largely absorbed into partially formed structures rather than complete capsids at both crowding levels. There is, however, a noticeable shift in the crowding simulations toward smaller partial intermediates.

Fig. 3, c, f, and i, show the effects on assembly trajectories as crowding is increased to 40%. CCMV shows a greatly increased assembly rate for the majority of potential capsids, to the point that the process no longer appears nucleation limited. Although the nucleation-like peaks are still present, they now overlap, indicating multiple capsids in their elongation phases simultaneously. The second, third, and fourth capsids assemble nearly simultaneously. The fifth, however, takes far longer than the original four to assemble, as the effects of reduced free subunits greatly slow bond formation. We note that this slow growth yields an opportunity to observe step-by-step addition of each subassembly to the growing capsid. A combination of single dimer, dimer-of-dimers, and trimer-of-dimers additions all occur during the assembly process.

A similar pattern can be seen with regard to HBV in Fig. 3 f. At 40% crowding, assembly is greatly accelerated relative to lower crowding levels. Peaks corresponding to nucleation and subsequent growth of individual capsids remain clearly defined, unlike in the CCMV case, but nonetheless begin to run together. One feature of note in the 40% crowding case is the presence of a small pool of pentamers-of-dimers early in the assembly process before the rapid nucleation and assembly of the first four capsids. In each case, only four of the five potential capsids are produced. It is also notable that after the last capsid is formed, there are no assemblies present other than persistent populations of completed capsids, single dimers, dimers-of-dimers, and trimers-of-dimers, and the transient appearance of occasional tetramers-of-dimers. There is no construction of pentamers-of-dimers, which are often seen forming shortly before a nucleation step in HBV trajectories.

For HPV assembly, the sample trajectory for 40% crowding in Fig. 3 i shows a qualitatively similar picture to that for 20% crowding in Fig. 3 h. The system is unable to produce completed capsids, instead yielding a spectrum of partially built, kinetically trapped forms. There is a further noticeable shift toward smaller trapped species relative to the uncrowded case. Meaningful differences between 20% and 40% crowding are difficult to discern from single trajectories, although Fig. 1 c implies that the shift toward smaller trapped species continues as crowding levels increase.

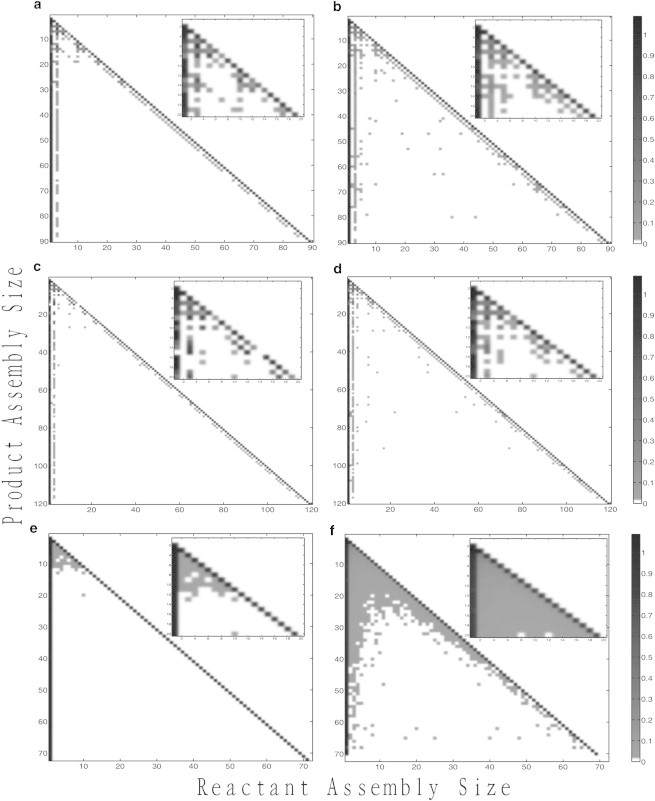

Measuring average pathway usage across trajectories

Another way to examine the changes seen in the assembly pathways for these viruses is to measure frequencies with which individual bonds are observed, averaged over many trajectories. Fig. 4 shows a visualization of these bond frequency tables, showing relative frequencies with which different assembly sizes are used as reactants in producing any given larger assembly size (e.g., the frequency with which a dimer is a reactant to a reaction producing a pentamer). Fig. 4, a and b, show the progression in bond frequency tables for CCMV at negligible and 40% crowding, in each case averaged over 100 simulation trajectories. Both crowding levels yield similar bond usage patterns, with essentially the same combinations of reaction steps. In each case, assembly proceeds by addition of either subunit monomers (coat dimers), subunit trimers (coat trimers-of-dimers), or, in some early steps, subunit pentamers (coat pentamers-of-dimers). Most steps favor monomer addition with a low frequency of trimer addition, aside from a few conserved steps with high trimer frequency early in assembly. However, two changes are noted in the 40% crowding case. First, there is an overall trend toward an increased use of single dimers versus trimers-of-dimer or pentamers-of-dimer at 40% crowding. Second, there is an increased frequency of reactions involving larger intermediates in the 40% crowding case, potentially out of necessity as binding reactions become less kinetically favorable.

Figure 4.

Binding frequency tables for CCMV at crowding levels of 0% (a) and 40% (b), HBV at crowding levels of 0% (c), and 40% (d), and HPV at crowding levels of 0% (e) and 40% (f). Each pixel shows the frequency with which a particular reactant size (x axis) is used to produce a particular product size (y axis). A scale bar relating shading to frequency appears on the right.

Fig. 4, c and d, show comparable plots for the HBV model. For HBV, as for CCMV, we see a pathway characterized predominantly by monomer addition, with a lesser rate of trimer addition. There are, however, a few conserved steps at which trimer addition is used preferentially. HBV shows only rare pentamer additions at a few early steps. As with CCMV, pathways are qualitatively similar across crowding levels, but again a slight trend occurs toward increased preference for assembly by single dimers versus other small oligomers and more frequent appearances of interactions between larger assemblies at 40% crowding.

Fig. 4, e and f, show a very different portrait again for HPV. As in our previous work (19,20), we find that HPV assembly is driven almost entirely by single capsomer additions. However, as crowding levels increase, the frequency of other binding events occurring also begins to increase. By the 40% crowding level every binding combination of sizes is observed at least infrequently among the lower assembly sizes. Thus, although crowding reduces the frequency of usage of minor assembly pathways for CCMV and HBV, it increases their use for HPV. We note that the final two rows of the HPV bond frequency table for 40% crowding are all white, showing that no binding events result in assemblies of >70 capsomers (HPV consists of 72 capsomers in our model) and thus that the HPV model was unable to assemble any complete capsids at the 40% crowding level.

Conclusion

This work is intended to take one step toward transitioning capsid assembly simulation away from models of in vitro environments toward more realistic representations of in vivo capsid assembly, with a specific focus on modeling the possible effects of macromolecular crowding on assembly. By using a previously developed approach for inferring the influence of crowding on association and dissociation rates of assembly reactions, we adjusted models of capsid assembly learned from in vitro data to better reflect how the coat subunits studied might behave in a crowded environment such as a living cell. Although the exact effects of crowding are notoriously hard to predict with accuracy, we can infer general trends by scanning across a range of possible simulated crowding levels. The resulting computational models made it possible to analyze detailed simulated assembly trajectories for three different icosahedral viruses—CCMV, HBV, and HPV—under levels of crowding between 0% and 45%, a range that should span the range from typical in vitro to plausible in vivo crowding levels.

The study revealed an important distinction between the effects of crowding on nucleation-limited capsid assembly and nonnucleation-limited capsid assembly. In particular, growth in the absence of a defined nucleation step generally was impeded by crowding, as the net acceleration of coat-coat binding led primarily to increased kinetic trapping and thus to a loss of productive assembly. Nucleation-limited growth, previously known to provide protection against kinetic trapping (19,21), appeared to provide a similar buffer against kinetic trapping that would otherwise be induced by crowding, allowing crowding to accelerate rather than inhibit productive assembly. We can speculate that the reason this effect can occur in our detailed assembly models is that nucleation is not a single step; crowding-induced changes in both forward and reverse rates of intermediate steps leading to nucleation can simultaneously slow each individual assembly step and yet accelerate the overall assembly rate. Furthermore, nucleation-limited assembly buffers against off-pathway growth, allowing this acceleration without an increase in off-pathway assembly over at least a broad range of crowding levels.

This enhancement of assembly through crowding operates over a limited range of crowding levels as the buffer effect will eventually break down when nucleation events occur in too rapid succession, which we begin to see for CCMV at the highest crowding levels. Nucleation-limited growth allows crowding to work to promote effective growth, but a sufficiently strong crowding effect will itself block nucleation-limited growth. These effects are evident in a shift of both of the nucleation-limited capsids toward a single monomer-accretion pathway, evident in Fig. 4, as well as in the overlapping nucleation/elongation peaks seen for these viruses in 40% crowding trajectories in Fig. 3. These results suggest that crowding is neither inherently a benefit nor a disadvantage to capsids, but rather a complicated effect variable across biologically plausible parameter domains. One can conjecture that viruses would evolve to function effectively in the domains in which they operate in nature. Understanding these tradeoffs may be helpful in better designing in vitro systems for capsids or other complex self-assemblies as well as in the design of novel self-assembling nanotechnology that might take advantage of similar environmental factors.

A key question for this work is to understand the degree to which we can trust that results from models, whether computational or in vitro, accurately reflect what happens in the cell. Our simulations suggest a mixed answer. Our results suggest that, at least for nucleation-limited assembly processes, assembly mechanisms and pathways are well conserved over a broad range of crowding values likely to cover both in vitro and in vivo levels of crowding. This observation would suggest that one can, indeed, use conclusions from the in vitro system to make predictions about pathways in vivo. This is a question that may have important practical consequences, such as for strategies for developing capsid assembly targeted antivirals (54–56). On the other hand, our models suggest significant quantitative differences in assembly rate and yield can be induced by crowding and that one thus cannot make accurate quantitative predictions about yield of a capsid system without adequately accounting for crowding in that system. This observation, too, may have important practical consequences. For example, one might expect that changes in usage of minor assembly pathways could substantially alter a virus’s ability to resist an assembly targeted drug.

The work presented here is intended to make one step forward in understanding how conditions in the cell might alter pathways for complex self-assemblies such as a viral capsid, with focus on the specific factor of molecular crowding, but it still falls far short of a real representation of viral capsid assembly in vivo. Designing computational models that better represent the conditions in which viruses normally assemble is essential to developing biologically accurate and predictive models of virus assembly in vivo. Furthermore, crowding effects themselves are complex and difficult to predict. We cannot claim that any particular parameter choices in our model will accurately measure the effect of crowding on the specific viral systems examined here. By exploring a range of values of crowding effects and the general trends across that range, we can, however, make general observations likely to prove useful despite imprecision in predicting crowding effects precisely. Nonetheless, improved crowding models or better empirical evidence from which to parameterize them for these specific systems would be valuable in making more specific and confident predictions. Furthermore, numerous other factors interact with growing capsids in the cell, including a diverse array of binding partners, chaperones, cytoskeletal structures, nucleic acid to be packaged or encapsidated in the final capsid product, and likely other actors not yet known to us. Determining which of these are actually relevant to modulating assembly pathways and how they act, singly and in combination, will require extensive work, both experimental and computational.

This work might be advanced in several ways. First, as both our prior work and the present work shows, the sequences of reaction steps needed for nucleation and growth inferred by our models are more complicated than simple nucleation-growth models have generally assumed, with growth proceeding in a complicated cascade of seemingly idiosyncratic but often clearly conserved patterns of interactions of different specific intermediate species. Better understanding these specific steps, and how variations in environment modulate them, remains a challenging but important problem. A further issue is more precisely and reliably predicting the specific parameters underlying the simulations. In part, that is an issue of eliminating uncertainty in the inferences of parameters in vitro, which might be accomplished by more extensive or richer experimental data from which to learn and improved algorithms for model fitting. Simulations must inherently make tradeoffs between model complexity, computational efficiency, and learnability of model parameters. As computing power, algorithms, and experimental methods for monitoring capsid assembly improve, it should become possible to move to more detailed and realistic models. Future extensions might include larger parameter sets accounting for potential allosteric interactions between subunits, flexibility in bonding to allow for misassembly of capsids, more detailed models of ensembles of molecules contributing to crowding, and models of other cellular components that might influence the assembly process. Fulfilling this long-term agenda of realistic models of assembly in the cell will require not just computational advances but also developing a better knowledge of the many other factors that influence virus capsid assembly in the cell and developing more precise quantitative models of how these factors influence the assembly process in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by U.S. National Institute of Health Awards 1R01AI076318 (G.S., L.X., B.L., and R.S.) and 1R01CA140214 (R.S.).

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Zlotnick A. To build a virus capsid. An equilibrium model of the self assembly of polyhedral protein complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;241:59–67. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zlotnick A., Johnson J.M., Endres D. A theoretical model successfully identifies features of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14644–14652. doi: 10.1021/bi991611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moisant P., Neeman H., Zlotnick A. Exploring the paths of (virus) assembly. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1350–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsiang M., Niedziela-Majka A., Sakowicz R. A trimer of dimers is the basic building block for human immunodeficiency virus-1 capsid assembly. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4416–4428. doi: 10.1021/bi300052h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagan M.F., Elrad O.M. Understanding the concentration dependence of viral capsid assembly kinetics—the origin of the lag time and identifying the critical nucleus size. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morozov A.Y., Bruinsma R.F., Rudnick J. Assembly of viruses and the pseudo-law of mass action. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:155101-1–155101-17. doi: 10.1063/1.3212694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan M.F., Chandler D. Dynamic pathways for viral capsid assembly. Biophys. J. 2006;91:42–54. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elrad O.M., Hagan M.F. Mechanisms of size control and polymorphism in viral capsid assembly. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3850–3857. doi: 10.1021/nl802269a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapaport D.C. Molecular dynamics simulation of reversibly self-assembling shells in solution using trapezoidal particles. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2012;86:051917-1–051917-7. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.051917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna V., Ayton G.S., Voth G.A. Role of protein interactions in defining HIV-1 viral capsid shape and stability: a coarse-grained analysis. Biophys. J. 2010;98:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen H.D., Reddy V.S., Brooks C.L., 3rd Deciphering the kinetic mechanism of spontaneous self-assembly of icosahedral capsids. Nano Lett. 2007;7:338–344. doi: 10.1021/nl062449h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahalik J.P., Muthukumar M. Langevin dynamics simulation of polymer-assisted virus-like assembly. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;136:135101-1–135101-13. doi: 10.1063/1.3698408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen T.T., Bruinsma R.F. Continuum theory of retroviral capsids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:078102–078105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.078102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levandovsky A., Zandi R. Nonequilibirum assembly, retroviruses, and conical structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:198102–198105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.198102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston I.G., Louis A.A., Doye J.P. Modelling the self-assembly of virus capsids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2010;22:104101–104110. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/10/104101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsawy K.M., Caves L.S., Twarock R. The impact of viral RNA on the association rates of capsid protein assembly: bacteriophage MS2 as a case study. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;400:935–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grime J.M.A., Voth G.A. Early stages of the HIV-1 capsid protein lattice formation. Biophys. J. 2012;103:1774–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baschek J.E., R Klein H.C., Schwarz U.S. Stochastic dynamics of virus capsid formation: direct versus hierarchical self-assembly. BMC Biophys. 2012;5:22-1–22-18. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang T., Schwartz R. Simulation study of the contribution of oligomer/oligomer binding to capsid assembly kinetics. Biophys. J. 2006;90:57–64. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misra M., Lees D., Schwartz R. Pathway complexity of model virus capsid assembly systems. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2008;9:277–293. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sweeney B., Zhang T., Schwartz R. Exploring the parameter space of complex self-assembly through virus capsid models. Biophys. J. 2008;94:772–783. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar M.S., Schwartz R. A parameter estimation technique for stochastic self-assembly systems and its application to human papillomavirus self-assembly. Phys. Biol. 2010;7:045005-1–045005-24. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/7/4/045005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie L., Smith G.R., Schwartz R. Surveying capsid assembly pathways through simulation-based data fitting. Biophys. J. 2012;103:1545–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kegel W.K., Schoot Pv Pv. Competing hydrophobic and screened-coulomb interactions in hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3905–3913. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venter P.A., Krishna N.K., Schneemann A. Capsid protein synthesis from replicating RNA directs specifics packaging of the genome of a multipartite, positive-strand RNA virus. Virology. 2005;79:6239–6248. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6239-6248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dykeman E.C., Stockley P.G., Twarock R. Building a viral capsid in the presence of genomic RNA. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2013;87:022717-1–022717-12. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.87.022717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin B.Y., Makhov A.M., Chow L.T. Chaperone proteins abrogate inhibition of the human papillomavirus (HPV) E1 replicative helicase by the HPV E2 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6592–6604. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6592-6604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verchot J. Cellular chaperones and folding enzymes are vital contributors to membrane bound replication and movement complexes during plant RNA virus infection. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:275-1–275-12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minton A.P. The influence of macromolecular crowding and macromolecular confinement on biochemical reactions in physiological media. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10577–10580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmerman S.B., Minton A.P. Macromolecular crowding: biochemical, biophysical, and physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1993;22:27–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeDuc P.R., Schwartz R. Computational models of molecular self-organization in cellular environments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007;48:16–31. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellis R.J. Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:597–604. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rincón V., Bocanegra R., Mateu M.G. Effects of macromolecular crowding on the inhibition of virus assembly and virus-cell receptor recognition. Biophys. J. 2011;100:738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.del Alamo M., Rivas G., Mateu M.G. Effect of macromolecular crowding agents on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein assembly in vitro. J. Virol. 2005;79:14271–14281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14271-14281.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reference deleted in proof.

- 36.McGuffee S.R., Elcock A.H. Diffusion, crowding & protein stability in a dynamic molecular model of the bacterial cytoplasm. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balbo J., Mereghetti P., Wade R.C. The shape of protein crowders is a major determinant of protein diffusion. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1576–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mittal J., Best R.B. Dependence of protein folding stability and dynamics on the density and composition of macromolecular crowders. Biophys. J. 2010;98:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee B., Leduc P.R., Schwartz R. Stochastic off-lattice modeling of molecular self-assembly in crowded environments by Green’s function reaction dynamics. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2008;78:031911-1–031911-9. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.031911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee B., LeDuc P.R., Schwartz R. Three-dimensional stochastic off-lattice model of binding chemistry in crowded environments. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillespie D.T. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J. Phys. Chem. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jamalyaria F., Rohlfs R., Schwartz R. Queue-based method for efficient simulation of biological self-assembly systems. J. Comput. Phys. 2005;204:100–120. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casini G.L., Graham D., Wu D.T. In vitro papillomavirus capsid assembly analyzed by light scattering. Virology. 2004;325:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finnen R.L., Erickson K.D., Garcea R.L. Interactions between papillomavirus L1 and L2 capsid proteins. J. Virol. 2003;77:4818–4826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4818-4826.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou S., Standring D.N. Hepatitis B virus capsid particles are assembled from core-protein dimer precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10046–10050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenney J.M., von Bonsdorff C.H., Fuller S.D. Evolutionary conservation in the hepatitis B virus core structure: comparison of human and duck cores. Structure. 1995;3:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zlotnick A., Aldrich R., Young M.J. Mechanism of capsid assembly for an icosahedral plant virus. Virology. 2000;277:450–456. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Speir J.A., Munshi S., Johnson J.E. Structures of the native and swollen forms of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus determined by X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Structure. 1995;3:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00135-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Zon J.S., ten Wolde P.R. Green’s-function reaction dynamics: a particle-based approach for simulating biochemical networks in time and space. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:234910-1–234910-16. doi: 10.1063/1.2137716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katen S.P., Chirapu S.R., Zlotnick A. Trapping of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly intermediates by phenylpropenamide assembly accelerators. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:1125–1136. doi: 10.1021/cb100275b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuma R., Tsuruta H., Prevelige P.E. Detection of intermediates and kinetic control during assembly of bacteriophage P22 procapsid. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:1395–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson J.M., Tang J., Zlotnick A. Regulating self-assembly of spherical oligomers. Nano Lett. 2005;5:765–770. doi: 10.1021/nl050274q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hagan M.F., Elrad O.M., Jack R.L. Mechanisms of kinetic trapping in self-assembly and phase transformation. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:104115-1–104115-13. doi: 10.1063/1.3635775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fader L.D., Landry S., Simoneau B. Optimization of a 1,5-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]diazepine-2,4-dione series of HIV capsid assembly inhibitors 2: structure-activity relationships (SAR) of the C3-phenyl moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:3401–3405. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li D., Dong H., Qiu H.J. Hemoglobin subunit beta interacts with the capsid protein and antagonizes the growth of classical swine fever virus. J. Virol. 2013;87:5707–5717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03130-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lingappa U.F., Wu X., Rupprecht C.E. Host-rabies virus protein-protein interactions as druggable antiviral targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E861–E868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210198110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krissinel E., Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voss N.R., Gerstein M., Moore P.B. The geometry of the ribosomal polypeptide exit tunnel. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;360:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.