Abstract

Cities are increasingly adopting CeaseFire, an evidence-based public health program that uses specialized outreach workers, called violence interrupters (VIs), to mediate potentially violent conflicts before they lead to a shooting. Prior research has linked conflict mediation with program-related reductions in homicides, but the specific conflict mediation practices used by effective programs to prevent imminent gun violence have not been identified. We conducted case studies of CeaseFire programs in two inner cities using qualitative data from focus groups with 24 VIs and interviews with eight program managers. Study sites were purposively sampled to represent programs with more than 1 year of implementation and evidence of program effectiveness. Staff with more than 6 months of job experience were recruited for participation. Successful mediation efforts were built on trust and respect between VIs and the community, especially high-risk individuals. In conflict mediation, immediate priorities included separating the potential shooter from the intended victim and from peers who may encourage violence, followed by persuading the parties to resolve the conflict peacefully. Tactics for brokering peace included arranging the return of stolen property and emphasizing negative consequences of violence such as jail, death, or increased police attention. Utilizing these approaches, VIs are capable of preventing gun violence and interrupting cycles of retaliation.

Keywords: Youth violence prevention, Conflict mediation, Community outreach

Introduction

Despite recent reductions in the nationwide violent crime rate,1 high rates of gun violence remain endemic in the USA.2 Gun violence is a leading cause of death for adolescents and young adults in many urban areas with concentrated disadvantage.3,4

The Institute of Medicine has endorsed the idea that gun violence can act as a social contagion.5 Violence can spread via retaliatory shootings,6 fueled by the perception that the “code of the street” requires one to respond to violence with violence to maintain social standing.7,8 Interventions to change the circumstances that lead to violence and counteract the social norms that foster the use of violence are needed.

Physician–epidemiologist Gary Slutkin developed the CeaseFire program (now called Cure Violence) with the goal of blocking the social transmission of violence.9 In the most violent neighborhoods, “violence interrupters” (VIs) are trained to mediate impending or ongoing street conflicts before a shooting occurs.9 Typically, VIs are from the communities in which they work. Many have formerly been involved in gangs, drug selling, or other high-risk activities, making them “credible messengers” within the target population of conflict-involved youth.9 A VI may connect youth with outreach workers (OWs) who serve as case managers to help youth access needed social services and work on longer-term lifestyle objectives, such as leaving a gang. The program model also includes community mobilization and public education to change local norms about the acceptability of violence.9,10

In Chicago, CeaseFire reduced gun violence in four of the seven neighborhoods where it was implemented and evaluated.9 Baltimore's replication of CeaseFire showed program-related reductions in gun violence in three of four neighborhoods where it operated; neighborhoods with more conflict mediations had greater reductions in homicides.11 Baltimore used hybrid outreach workers (HOWs) who engaged in violence interruption and maintained a caseload of high-risk youth participants whom they mentored and referred to needed services.

Communities in the USA and internationally have implemented CeaseFire12,13 and similar program models14,15 in an effort to reduce gun violence. Despite the growing popularity and promise of street conflict mediation as a direct approach to violence prevention,11,16 relatively little research has examined the key components and processes,14 and no studies have examined variations in conflict mediation practices across programs. Such knowledge could benefit communities implementing CeaseFire or similar programs and provide a foundation for future research to evaluate which mediation practices are statistically associated with positive outcomes. Accordingly, we examined conflict mediation across multiple program sites and sought to describe: (1) VI characteristics, (2) how VIs learn about street conflicts, (3) the process of street conflict mediation, (4) mediation tactics and tools, and (5) challenges for such mediation efforts.

Methods

We conducted a multiple-case study to examine street conflict mediation as it is shaped by contextual factors including characteristics of the implementing organizations and the local community.17 We selected two cities' CeaseFire programs as cases. Each case had embedded units of analysis17 in the form of the neighborhood program sites. The use of two cases, with embedded subunits, allowed for comparisons within and across cases. A written protocol was followed throughout data collection and analysis to help ensure similar processes were followed in conducting the case studies. The Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health approved this research.

Case Study Site Selection

Inclusion criteria specified that cases had to be a city formally utilizing the CeaseFire model and have program evaluation results available. Programs in ten cities were considered, but the original CeaseFire Chicago program and its replication in Baltimore were the only programs to meet these criteria. Within each city, we included neighborhood sites that had been in operation for at least 1 year. In Baltimore, where the program is called Safe Streets, two program sites met the criteria: (1) Safe Streets East, which had separate outreach teams for the three East Baltimore neighborhoods of McElderry Park, Ellwood Park, and Madison-Eastend, and (2) Safe Streets Cherry Hill in South Baltimore. Because some Baltimore sites faced challenges with implementation,11 it was important to compare Safe Streets with CeaseFire sites that operate with high fidelity to the model. We asked senior CeaseFire staff to identify the Chicago sites with at least 1 year in operation that they consider to have the highest fidelity to the original model. Following their recommendation, we included: (1) CeaseFire West, operating in West Garfield Park and West Humboldt Park, and (2) CeaseFire Englewood in South Chicago. Table 1 shows demographic and crime characteristics for the neighborhoods included in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of neighborhoods included in case studies of street conflict mediation practices

| Chicago | Baltimore | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeaseFire Westa | Englewooda | McElderry Park | Ellwood Park | Madison-Eastend | Cherry Hill | |

| Populationb | 20,825 | 13,950 | 4033 | 3580 | 2487 | 8367 |

| Age 15–24b, n (%) | 3,592 (17.2) | 2,506 (18.0) | 763 (18.9) | 581 (18.6) | 445 (17.9) | 1,237 (16.6) |

| Race/ethnicityb, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 2,857 (13.7) | 112 (0.8) | 382 (9.5) | 415 (11.6) | 54 (2.2) | 238 (2.8) |

| Black | 14,45 (69.4) | 13,576 (97.3) | 3,238 (80.3) | 2,647 (73.9) | 2,371 (95.3) | 7,919 (94.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5,973 (28.7) | 254 (1.8) | 473 (11.7) | 501 (14.0) | 53 (2.1) | 140 (1.7) |

| Other | 3,036 (14.6) | 125 (0.9) | 271 (6.7) | 392 (10.9) | 31 (1.2) | 99 (1.2) |

| Median household incomec | $24,742 | $29,261 | $33,352 | $33,352 | $33,352 | $18,602 |

| Unemploymentc (%) | 9.1 | 15.8 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 23.8 |

| Female-headed households, %b | 37.9 | 43.8 | 61.5 | 60.6 | 63.8 | 71.9 |

| Vacant housing units, %b | 19.8 | 18.8 | 31.8 | 23.2 | 18.6 | 7.0 |

| Annual homicidesd | 11 | 10.5 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Annual nonfatal shootingsd | 49.3 | 48.8 | 9.8 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 12.8 |

aData are presented for the police beats where the CeaseFire program operates. The CeaseFire West site encompasses parts of West Garfield Park and West Humboldt Park neighborhoods; the Englewood site encompasses parts of West Englewood

bDemographic data from the 2010 census17

cEconomic data from 2006–2010 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates. Chicago estimates are for the census tracts comprising the target neighborhood. Baltimore estimates are for community statistical area (CSA) including neighborhood of interest. McElderry Park, Ellwood Park, and Madison-Eastend are in the same CSA18

dChicago or Baltimore Police Department data, 2003–2006 average

Data Collection

Consistent with the case study method, the study utilized multiple sources of data.17 This paper focuses on data collected from focus groups with HOWs and VIs, interviews with neighborhood program managers, and program documents. Data were collected between June 2010 and July 2011. Informed consent, including permission to audio-record, was obtained prior to the start of each focus group or interview. At the end of each session, participants were asked to provide copies of any documents that could inform our understanding of the program, such as training manuals, meeting agendas and minutes, and blank or de-identified program records. Participants received a $25 gift card for their participation.

Focus Groups

To recruit focus group participants, one author attended a regularly scheduled staff meeting at each neighborhood site. Using a recruitment script, she introduced herself and explained the research and eligibility criteria. All VIs and HOWs who had held their positions for at least 6 months were invited to participate in one of the focus groups. Focus groups were utilized to allow observation of group dynamics and the extent to which participants agree and disagree with each other's responses.18,19 We stratified focus group participants by their neighborhoods and job titles. A semi-structured focus group guide was used to direct the discussion while also allowing flexibility to pursue subjects raised by the participants.

The focus groups were conducted in a private room at the program offices. For the focus groups in Baltimore, a second author also attended as a notetaker; no notetaker was present during the Chicago focus groups. Participants were asked to describe their backgrounds, their connections to the community, their daily work routines, and how they mediate conflicts. They were encouraged to provide stories and examples from their work and to reflect on what worked and did not work well in the scenarios they described.

Site Manager Interviews

The management staff of each neighborhood site was invited to participate in a semi-structured, one-on-one interview. Using an interview guide, the interviewer asked managers to describe their role, the conflict mediation strategies they perceive as most effective, and the challenges workers face and how they address these challenges. Interviewees were encouraged to use examples when answering questions.

Data Analysis

Audio files were transcribed, validated, and added to an Atlas.ti (version 6.2) database.20 One author coded four focus group transcripts and two site-manager transcripts (evenly divided between the two cases) using an open-coding approach of marking segments of text that reflect unique ideas, meanings, or themes.21 These codes were added to a structured codebook and defined. A second author utilized the draft codebook to code two focus group transcripts and one manager interview transcript selected from the previously coded group. Both coders wrote memos to capture working theories, connections, and explanations as they emerged.21 Codes from both authors were merged into one database and compared; they discussed instances of disagreement and made refinements to the codebook accordingly. After both authors were satisfied with the codebook and their ability to apply codes consistently, a third coauthor with content and methodological expertise reviewed the resulting codebook for clarity and completeness. All documents obtained from the programs were also added to the database. One author used the final codebook to code the remaining transcripts and documents. A process of triangulation between documents and participants' descriptions of mediation practices were used to address the study aims. A brief summary report was written for each of the two cases and shared with research participants to assess the validity of our interpretation of the data.

Results

We conducted four focus groups with 15 HOWs in Baltimore and two focus groups with 9 VIs in Chicago for a total of 24 participants. With the exception of one VI who met the eligibility requirement but declined to participate for unknown reasons, all eligible staff participated in a focus group at their respective sites. Each focus group lasted approximately 2 h. All eight neighborhood site managers consented to participate in individual interviews that took about 1.5 h to complete.

Neighborhood Staff Characteristics

Participants were predominantly male and in their 30s and 40s; most were either current or former residents of the neighborhoods in which they work. Across both cases, about 75 % of the staff had been incarcerated (Table 2). All study participants emphasized that credibility—described as a combination of trustworthiness, authenticity, and an ability to relate to high-risk individuals and community members—is the most important characteristic for VIs and HOWs.

Table 2.

Violence interrupter, hybrid outreach worker, and site manager demographics

| Chicago | Baltimore | |||

| Violence interruptersa | Site managers | Hybrid outreach workersb | Site managers | |

| n = 9 | n = 4 | n = 15 | n = 4 | |

| Mean age | 43 | 47 | 37 | 46 |

| Age range | 29–54 | 37–60 | 29–65 | 40–48 |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Previously incarcerated | 8 | 3 | 11 | 3 |

| Resided or hung out in target neighborhood | 9 | 4 | 15 | 3 |

| Time in current job role (years) | ||||

| t < 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| 1 ≤ t < 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| 2 ≤ t < 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| t ≥ 3 | 7 | 0 | –c | –c |

aIn Chicago, violence interrupters conduct conflict mediation, and separate outreach workers serve as youth case managers

bHybrid outreach workers in Baltimore conduct conflict mediations and maintain a caseload of high-risk youth whom they mentor and connect to services

cThe Baltimore program had been operating for almost 3 years at the time of data collection, and CeaseFire Chicago had been operating for approximately 10 years

Identifying Street Conflicts

HOWs and VIs rely on the community to share information about potential shootings before they happen. Community members must trust that such information will not be shared with the police. Even when staffed by credible individuals, the program itself can be viewed with skepticism and distrust initially. When CeaseFire is first implemented, the staff walk through the area engaging residents and explaining the program and its mission. In Baltimore, HOWs began some of these interactions saying “Yo, this is Safe Streets, we don't work with the police, ain't no snitching stuff.” This overt effort to quell suspicion of snitching was viewed by site managers in both cities as a beneficial adaptation for the Baltimore context.

VIs and HOWs ask community residents to contact the program if they hear of a fight or brewing conflict that could escalate to serious violence. They pass out literature and business cards with the program's phone number to make it easy for residents to get in touch. But, in both Chicago and Baltimore, workers emphasized the importance of being out in the community to observe for themselves. They look for unusual patterns in the neighborhood, such as unfamiliar cars driving around, certain groups of people not hanging out where they usually do, palpable tension, or signs of secretive behavior. As one VI described:

Sometimes you just can look at the guys and know. You can feel the tension. Certain things may change [from] what they were doing a day before. They may have a hoodie on—you know what I'm saying? It's like “why you put the damn hoodie on your head this time year?” It's kind of warm.

VIs and HOWs focus extra attention on cultivating relationships with key individuals they call “inroads,” who are close to or influential on the streets and in gangs. VIs and HOWs urge inroads to contact the program if someone they know has an issue with another individual or group and is considering a violent response. To encourage reporting, program staff point out that shootings attract police attention that, in addition to the threat of arrest, can disrupt street markets and prevent everyone involved from earning money.

Conflict Mediation Tactics

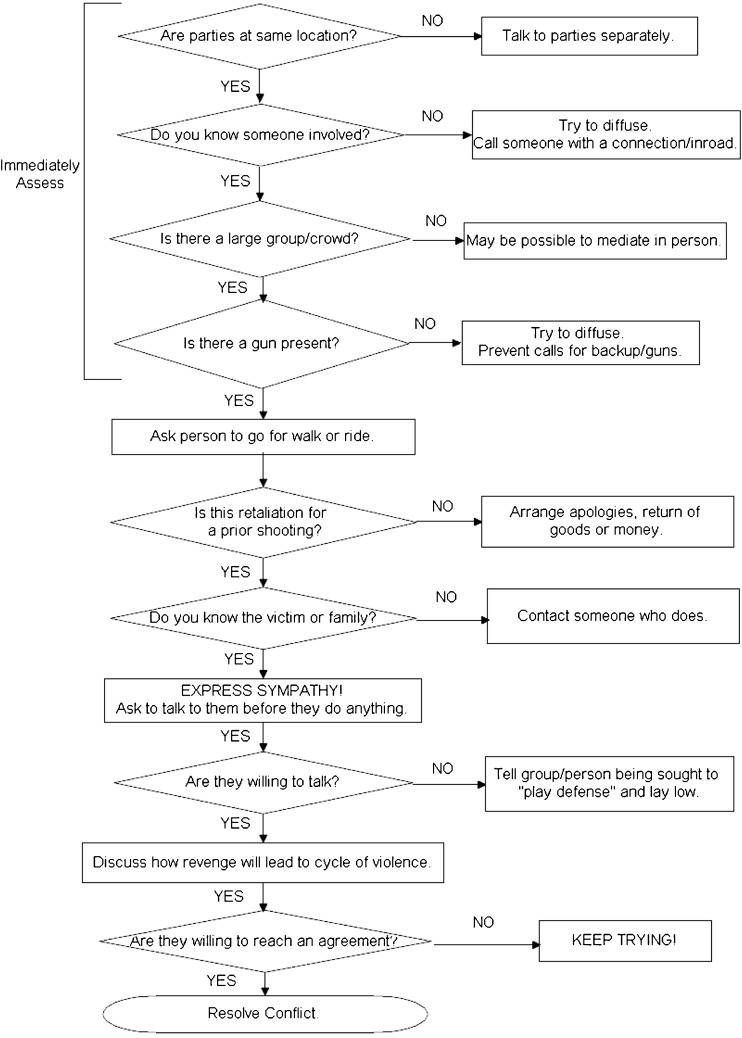

Conflict mediation is a complex interaction between the individuals with the conflict and the program staff. HOWs and VIs intervene at various stages of conflict; some mediations involve breaking up physical fights, and others involve speaking with an individual or group about their intended actions. Figure 1 displays a model of key considerations that VIs and HOWs assess during mediation and steps they may take accordingly, developed from accounts of conflicts mediated.

Figure 1.

Key considerations and actions during street conflict mediation. Note: This figure was derived from accounts of mediated conflicts. The first four steps may occur simultaneously or in a different order, depending on the specific situation.

VIs and HOWs described their first priorities as (1) buying time, (2) separating the potential shooter from the intended victim, and (3) separating the potential shooter from the group, if there are others around, egging him on. All outreach workers described their ultimate goal as getting the two parties, in person, to verbally agree the conflict is over. Even after such an agreement has been reached, outreach staff follow up to make sure that the parties maintain the peace.

VIs and HOWs use their judgment and knowledge of the individuals to determine how assertive they can be in demanding nonviolence. Staff noted that respect is at the core of their interactions with individuals in conflicts they mediate, either from their reputation in the community or from their approach to the mediation. When VIs and HOWs know they are respected, they may raise their voices and forcefully tell the individuals why they should find a solution other than shooting. Other situations call for a more delicate approach in which HOWs or VIs empathize with the offended party, validating their emotional response, while trying to convince them not to act on that emotion by shooting. One HOW explained his approach with individuals he does not know well:

I'll have to be polite… just say you got a little kid and he ready to shoot someone and you catch him in the doing it. Now if I go to him aggressive he's looking at [me] like “Who's you?” Like “you disrespecting me.”

Since perceived disrespect can lead to violence, the staff are mindful of that line. Table 3 contains a list of specific tactics that VIs and HOWs use to influence people not to shoot. A combination of the tactics is often used in hopes that one resonates with the would-be shooter.

Table 3.

Conflict mediation tactics utilized by CeaseFire staff in Chicago and Baltimore to persuade individuals to avoid gun violence

| Agreement | Arrange return of stolen goods/money |

| Help parties establish mutually acceptable boundaries for territory | |

| Establish ceasefire or truce between groups | |

| Buying time | Waiting while angry person calms down |

| Inviting individual to get some food, go elsewhere, talk about the issue | |

| Blame VI | Encourages saying “VI asked me not to shoot” as a way to save face |

| Economics | Explains shooting is bad for business; will attract police attention |

| Can't earn money in jail | |

| Personal consequences | Points out effect of violence on parents, children, siblings |

| Emphasizes bad ending: jail or death | |

| VI story | Shares personal experiences with being in jail or other negative things |

| Potential | Reminds the person about goals and all the other things he could do with his life |

| Third parties | Asks friend or relative to convince individual he doesn't need to shoot |

| Talk to peers, people the shooter is trying to uphold his image to | |

| Makes appeal to gang leader or other key individual | |

| Questioning | Asks individual to explain why he needs to do this; think through actions |

| Yelling | Yells at individual; aggressively tells person not to shoot |

Masculine pronouns have been used because most shooters and potential shooters are male

Within the groups of VIs and HOWs, participants described how they use each other as a resource during mediations. Different staff members may have relationships with parties on each side of a conflict. At times, a VI or HOW will introduce the individual in conflict to their coworker who knows the other side and describe how these two VIs who were once in opposing groups are now friends and colleagues. They lead by example in this manner and encourage parties in conflict to see a future when differences can be put aside and a respectful relationship established.

Conflict Mediation Tools

All staff are given a cell phone, and in Chicago, VIs are expected to have a car. The car is often used to remove an angry, would-be shooter from the scene of a brewing conflict. Further, the car can be used to get conflicting individuals to locations where they will not bring a weapon, as one participant put it:

When I know it's a mediation where there's possibly guns involved I take it where they ain't going to bring the guns, to the Loop. We going to go downtown. They ain't take no gun downtown because… a bunch of black people, they going to get pulled over. It's just way it is.

During work hours, staff are required to have their CeaseFire or Safe Streets ID card and wear a uniform with bright orange writing and trim so they can easily be identified. Outreach staff in both cities stated that when they are out in the streets, they generally avoid contact with and maintain a respectful distance from police officers. Workers are also trained to stay away from drug and other illegal transactions to avoid getting caught up in police crackdowns. VIs and HOWs are required to be in pairs or groups when out in the community. They do not carry weapons or wear protective devices. One program manager noted that VIs/HOWs are out there “armed with only their wits and a cell phone.”

Conflict Mediation Challenges

In both cities, outreach staff reported that the hardest conflicts to mediate involve retaliation for a previous homicide and those where large amounts of money were involved. Yet, VIs and HOWs told of situations when they were able to prevent retaliation even after there had been multiple victims and social norms require retaliation. In Baltimore, HOWs noted difficulty in preventing shootings when the shooters came in from non-Safe Streets neighborhoods, and the program was not made aware of the impending violence. In contrast, VIs on the South Side of Chicago told stories of hearing that a group was coming over from the West Side with intent to shoot and being able to intervene successfully. They noted that this happens regularly, and they draw on connections with VIs from the 18 additional sites around the city.

Discussion

VIs and HOWs have amassed substantive practice-based evidence for effective conflict mediation. This study of six CeaseFire sites in two cities sought to learn from the experiences of those who mediate conflicts and their supervisors to identify key VI characteristics, processes, and tactics. Participants emphasized the need for credibility with the community and careful observation of behavioral patterns in order to find out about potential conflicts. Important aspects of the mediation process include: assessing presence of weapons, managing the influence of others on the parties threatening violence, and using prior knowledge and relationships with the individuals involved.

HOWs in Baltimore and Chicago VIs generally used similar approaches with some tailoring for the local context. Distrust of the police is an issue in many Black communities,22 like those studied here, but this was a particularly salient issue in Baltimore, which is notorious for its anti-snitching culture.23 Just as HOWs in Baltimore explicitly told community residents that the program does not provide information to the police, the process of introducing the program in a new area may require tailoring the message to fit the likely concerns of the specific community.

CeaseFire is not the only program to utilize street conflict mediation. Others, such as the United Teen Equality Center (UTEC) in Lowell, MA,14 and Los Angeles' Gang Reduction and Youth Development Program,24 also include mediation. One study of UTEC notes that conflict intervention may include negotiation, efforts to de-escalate the situation, physically stopping fights, and/or calling law enforcement.14 CeaseFire conflict mediation is similar, with the important exception that VIs and HOWs would avoid contacting the police out of concern for violating the trust and their relationship with individuals in conflict. Understanding how CeaseFire and similar programs maintain a positive relationship with the police without jeopardizing community trust is an important topic for future exploration.

Pittsburgh's One Vision One Life program, which is similar to CeaseFire in having both street outreach and conflict intervention components, was recently evaluated and found to be associated with increases in gun assaults.15 The evaluators noted that the outreach staff were not focused on systematic identification of potentially violent conflicts and did not put special emphasis on tracking retaliatory events or gang conflicts. Rather, they conducted mediations for conflicts encountered during the regular course of their work shift. Such results corroborate the participants' perspectives in the present study indicating that proactive efforts to learn about gang conflicts, retaliation, and minor incidents that could potentially lead to future violence are needed for this type of intervention to succeed.

Limitations and Strengths

The findings from this study cannot be generalized to suggest that outreach is practiced in other communities implementing CeaseFire just as it is in the cases described here. Rather, our intent was to illuminate key outreach practices in these specific cases. Qualitative studies, such as this, may be criticized for reliance on study participants' subjective accounts of their actions. The use of focus groups with staff who work together closely should have reduced the threat of recall bias—in focus groups, participants often jointly described scenarios and corrected each other if details were not accurately reported. To help guard against social desirability bias, and outreach staff portraying their actions only in positive terms, we prompted outreach staff to share their challenges and mistakes so that others might learn from them. Further, by using multiple methods of data collection, we were able to corroborate the facts of major events and processes described by participants. We aimed to improve the reliability and repeatability of our study through the double coding process and by maintaining a case study protocol. By providing participants with a summary of the findings and asking for their feedback on the results, we helped ensure that the conclusions reflect an accurate interpretation of the participants' perspectives and experiences.

Implications

By providing a systematic understanding of street conflict mediation, this study sets a foundation for future research that seeks to compare programs and to quantify the relationships between conflict mediation strategies, individual, conflict- and program-level outcomes. Understanding the situations in which certain outreach tactics are most effective could improve the CeaseFire/Cure Violence model and lead to greater and more consistent reductions in youth violence. The pathway model of conflict mediation developed through this research should be considered by leaders of CeaseFire/Cure Violence sites and similar programs for its application in their context, potentially as a training tool. The challenges raised by study participants might represent concerns that, if addressed, could lead to better program outcomes. In particular, retaliatory conflicts warrant additional attention, and program planners should consider the advantages of having a network of program sites in the most violent neighborhoods across a city so VIs from different areas can collaborate to solve conflicts that are not limited to one neighborhood.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the CDC (grant R36CE001683), the Johns Hopkins Urban Health Institute–Small Grants Program, and the Melissa Institute for Violence Prevention Belfer–Aptman Dissertation Research Award. The authors are grateful to the study participants and the staff at the Baltimore City Health Department and CeaseFire Chicago who helped to arrange data collection.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2010. In Washington, D.C.; 2011.

- 2.Christoffel KK. Firearm injuries: epidemic then, endemic now. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):626–629. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.085340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh G, Azuine R, Siahpush M, Kogan M. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among US youth: socioeconomic and rural–urban disparities and international patterns. J Urban Health. 2013 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Fabio A, Tu L-C, Loeber R, Cohen J. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and the shape of the age–crime curve. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(S1):S325–S332. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. The contagion of violence—a workshop. In Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences; 2011.

- 6.Copeland-Linder N, Johnson SB, Haynie DL, Chung SE, Cheng TL. Retaliatory attitudes and violent behaviors among assault-injured youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3):215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson E. Code of the street: decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich JA, Grey CM. Pathways to recurrent trauma among young black men: traumatic stress, substance use, and the “code of the street”. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):816–824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skogan WG, Hartnett SM, Bump N, Dubois J. Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago. Chicago: Northwestern University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The model. Cure Violence. http://cureviolence.org/what-we-do/the-model. Accessed October 15, 2012.

- 11.Webster D, Whitehill J, Vernick J, Curriero F. Effects of Baltimore's Safe Streets Program on gun violence: a replication of Chicago's CeaseFire program. J Urban Health. 2013 (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.International partners. Cure Violence. http://cureviolence.org/community-partners/international-partners. Accessed October 15, 2012.

- 13.National partners. Cure Violence. http://cureviolence.org/community-partners/national-partners. Accessed October 15, 2012.

- 14.Frattaroli S, Pollack KM, Jonsberg K, Croteau G, Rivera J, Mendel JS. Streetworkers, youth violence prevention, and peacemaking in Lowell, Massachusetts: lessons and voices from the community. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(3):171–179. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2010.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson JM, Chermak S. Community-driven violence reduction programs. Criminology & Public Policy. 2011;10(4):993–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00763.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitehill JM, Webster DW, Vernick JS. Street conflict mediation to prevent youth violence: conflict characteristics and outcomes. Inj Prev. 2013 (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Yin RK. Case study research design and methods. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research: introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atlas.Ti qualitative data analysis [computer program]. Version 6.2. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2010.

- 21.Miles MB, Huberman AM. An expanded sourcebook: qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunson RK. “Police don't like black people”: African–American young men's accumulated police experiences. Criminology & Public Policy. 2007;6(1):71–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asbury BD. Anti-snitching norms and community loyalty. Oregon Law Review. 2011;89(4):1257–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunworth T, Hayeslip D, Lyons M, Denver M. Evaluation of the Los Angeles gang reduction and youth development project: final Y1 report. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]