Abstract

Duck meat is less utilized than other meats in processed products because of limitations of its functional properties, including lower water holding capacity, emulsion stability, and higher cooking loss compared with chicken meat. These limitations could be improved using surimi technology, which consists of washing and concentrating myofibrillar protein. In this study, surimi-like materials were made from duck meat using two or three washings with different solutions (tap water, sodium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, and sodium phosphate buffer). Better improvement of the meat’s functional properties was obtained with three washings versus two washings. Washing with tap water achieved the highest gel strength; moderate elevation of water holding capacity, pH, lightness, and whiteness; and left a small amount of fat. Washing with sodium bicarbonate solution generated the highest water holding capacity and pH and high lightness and whiteness values, but it resulted in the lowest gel strength. Processing duck meat into surimi-like material improves its functional properties, thereby making it possible to use duck meat in processed products.

Keywords: Washed meats, Mechanical deboning, Duck meat, Surimi-like material

Introduction

Duck meat production has increased in last two decades and currently is the third most widely produced poultry meat after chicken and turkey (Chein Tai and Jui-Jane Liu Tai 2001; FAOSTAT 2009). However, because of its functional properties, duck meat is less utilized in processed meat products compared to chicken and turkey meat (Huda et al. 2011; Ramadhan et al. 2010). Bhattacharyya et al. (2007) reported that sausages made from duck meat had lower cooking yield and emulsion stability compared to those made from chicken. Biswas et al. (2006) found that patties made from duck meat had lower emulsion stability and cooking yield compared with chicken patties, and Ali et al. (2007) reported that duck meat had higher cooking loss, darker color, and a more rapid decline of shear force during storage compared to chicken meat. Huda et al. (2010) reported that duck sausage had low functional properties and lower sensory evaluation scores for texture and overall acceptability compared to chicken sausage. Thus, the functional properties of this abundant source of meat need to be improved so that it can be used in processed meat products.

Mechanical deboning is commonly used to acquire meat from poultry carcasses (Ozkececi et al. 2008). This mechanically deboned meat then can be used as raw material for processed meat products. However, it suffers from a short shelf life, susceptibility to oxidation, dark color, and low functional properties due to the mechanical stress that occurs during processing; it also contains fat, connective tissue, and bone marrow (Stangierski and Kijowski 2000; Souza et al. 2009). Surimi processing, which involves washing and concentrating myofibrillar protein, is one method of addressing these problems. The washing process removes undesired components such as blood, fat, sarcoplasmic proteins, and pigments, thereby allowing concentration of myofibrillar proteins (Piyadhammaviboon and Yongsawatdigul 2010; Montero et al. 1999; Karayannakidis et al. 2008). Surimi processing successfully changes low value fish flesh into meat with higher functional, textural, and color properties, which then can be processed further into various products. When the process is used on meats other than fish, the product is known as surimi-like material or washed meat (Nurkhoeriyati et al. 2010). Surimi-like material made from mechanically deboned poultry meat has been shown to have improved functional properties (Froning and McKee 2001; Smyth and O'Neill 1997; Stangierski et al. 2007).

Previous studies have reported that tap water, sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), and sodium phosphate buffer are useful washing solutions for surimi-like material processing. However, each solution affects surimi-like material properties differently e.g. difference on whiteness and WHC enhancement (Ensoy et al. 2004; Ismail et al. 2010; Smyth and O'Neill 1997; Yang and Froning 1992). Moreover, limited information is available about surimi-like material from duck meat. Thus, this study was conducted to examine the effects of 1) number of washings and 2) washing with different solutions on the functional properties of mechanically deboned broiler duck meat from Pekin ducks.

Materials and methods

Materials

Carcasses of 8 weeks-old broilers from Pekin ducks were mechanically deboned at a commercial processing plant (Fika Food Corporation Sdn. Bhd., Penang, Malaysia) using a deboning machine with a pore size of 0.9 mm (Meat Maker Deboner, Prince Industries Inc., Murrayville, Georgia, USA). The meat was stored in frozen meat block form. The washing solutions used were 1) tap water, 2) 0.1 M NaCl, 3) 0.5% NaHCO3, and 4) 0.04 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

Preparation of washed meat

Meat blocks were cut into smaller sizes and ground using a meat grinder. The ratio of meat to solution used was 1:3 on weight basis. A portion then was mixed with three portions of a cold solution (below 5°C) using a universal mixer for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min at <4°C using a Union 5KR centrifuge (Hanil Science Industrial, Co., Ltd., Incheon, Korea). The upper layer of fat and aqueous supernatant was discarded from the meat concentrate. For each solution, the washing process was conducted twice and three times so that the effect of number of washings on functional properties could be compared.

Cooked gel preparation

Washed (or unwashed) minces were combined with 3% salt and mixed using a cutter mixer (Blixer®, Robot Coupe USA, Inc., Jackson, Mississippi, USA) for 1 min until the mixture resembled a meat batter. The batter was stuffed into plastic casing cylinders (diameter 2 cm, height 15 cm). Stuffed batters were incubated in a water bath at 36°C for 30 min and then at 90°C for 10 min. They then were immediately placed in ice to obtain a core temperature of <10°C.

Chemical composition analysis and yields

Moisture, protein, and fat contents were analyzed according to AOAC methods (AOAC 2000). Moisture was determined using the air oven drying method at 110°C for 24 h. Protein content was evaluated using the Kjeldahl method, and fat content was measured using the Soxhlet method. Yield was determined through calculating the weight of washed meat (WM) and comparing to the weight of unwashed meat (UM). Fat removal was determined by calculating the difference of fat content between WM and UM. Protein recovery was determined by calculating the protein remained in WM divided by protein content of UM.

|

|

|

pH analysis

pH was measured using a digital pH meter (pH 211 microprocessor pH meter, Hanna Instrument®, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). About 5 g of meat were mixed with 45 ml of distilled water using a homogenizer (T25 digital ULTRA-TURRAX®, IKA®, Staufen, Germany) and the pH then was measured.

Water holding capacity (WHC)

WHC was analyzed according to Babji and Gna (1994) with modification. About 20 g of meat were mixed with 40 ml of distilled water using the homogenizer (T25 digital ULTRA-TURRAX®). Approximately 10 g of homogenate were weighed into a centrifugation tube and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the precipitate was weighed. WHC was expressed as grams of water per grams of protein of the meat (g water/g protein). Water holding capacity was calculated by the following formula:

|

Breaking force and gel strength

Breaking force and gel strength were measured using a TA-XT plus (Stable Micro Systems, Ltd., Surrey, UK) according to the method of Balange and Benjakul (2009). Cooked surimi gels were tempered at 20°C prior to measurement and then cut into 3 cm thick pieces. A piece of the gel was placed perpendicularly on platform surface, and the gel was penetrated by a spherical probe (type P/0.25) at a constant 1 mm/sec speed rate until 11 mm depth. The trigger force used was 5 g, with 1 mm/sec of pre-test speed and 10 mm/sec of post-test speed. The load cell capacity of the texture analyzer was 5 kg and the return distance was 35 mm. Gel strength (g mm) was the result of multiplying breaking force (g) with deformation (mm).

Myoglobin content

Myoglobin content was analyzed using the method described by Jin et al. (2007a) with slight modification. Two grams of sample were homogenized with 20 ml of 0.04 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) at 13,500 rpm for 20 s. Next, 10 g of homogenate were placed in a centrifugation tube and centrifuged at 4000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered with Whatman No.1 filter paper, and 0.2 ml of 1% (w/v) sodium dithionite were added to the filtrate. Myoglobin content was measured using a spectrophotometer (UV 160, Shimadzu, Co., Kyoto, Japan) at 555 nm with millimolar extinction coefficient of 7.6 and a molecular weight of 16,111.

Color analysis

Color properties [L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness)] of the cooked surimi gels were measured using a Minolta CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta Sensing Americas, Inc. New Jersey, USA). Whiteness was calculated using the following formula (Park 2005):  .

.

Protein solubility

Protein solubility was determined using method of Venugopal et al. (1996). One gram of meat was added to 40 ml 3% NaCl solution. A Stuart SA7 vortex mixer (Bibby Scientific Limited, Staffordshire, UK) was used for 2 min to homogenize the samples. Aliquots were centrifuged at speed 6280 g for 5 min using Heraeus Multifuge X1R centrifuge (Thermo Electron LED GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Supernatant was collected for protein analysis. Protein solubility was calculated on the basis of whole protein content of the meat and expressed in percentage.

|

Texture profile analysis

The texture profile, which included hardness, chewiness, cohesiveness, and springiness, was measured using a TA-HDi (Stable Micro Systems, Ltd., Surrey, UK). Cooked surimi gels were tempered at 20°C prior to measurement and then cut into 3 cm thick pieces. A piece of gel was placed horizontally on the platform, and then the gel was compressed with a P75 probe at a constant 1 mm/sec speed rate. The trigger force used was 10 g, with 3 mm/sec of pre-test speed post-test speed. The load cell capacity of the texture analyzer was 25 kg and the return distance was 35 mm. Hardness, springiness, and cohesiveness were calculated from force-distance curve generated for each sample. Hardness refers to the highest peak force obtained on first compression. Cohesiveness is defined as the ratio of positive force area on the curve during second pressing to that of the first pressing. Chewiness is calculated as the product of gumminess and springiness. Gumminess is a product of hardness and cohesiveness. Springiness refers to the recovery of the food’s height between the end of first compression cycle and the start of second cycle (Deshpande 2001; Hayes et al. 2005).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Method for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) referred to the works of Nurkhoeriyati et al. (2011). Microstructure of the cooked gels was evaluated using electron microscopy (LEO Supra 50 VP Field Emission SEM Carl-Ziess SMT, Oberkochen, Germany). Cooked gels were cut 5 mm thick and freeze-dried (Labconco Co., Kansas City, Mo., U.S.A.). The dried samples were mounted on a bronzes tub and sputter-coated with gold. The specimens were scanned using variable pressure secondary electron (VPSE) signal.

Statistical analysis

There were eight different treatment combinations of surimi-like materials (two and three washings using four solutions) and one unwashed meat as control. Each surimi-like material was made in duplicate. All chemical and physical analyses were performed three times for each duplicate sample. Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparison of means was performed using Duncan’s multiple-range test with level of significance 0.05. Pearson’s correlation method was used to analyze correlations between several parameters i.e. moisture, fat, protein, pH, WHC, myoglobin, color, and gel strength. Analysis was performed using SPSS software (SPSS 16.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Chemical composition, yield, fat removal, and protein recovery

Table 1 shows the chemical compositions of unwashed and washed meat. The number of washings had a significant effect on the increase of moisture content and on the reduction of fat content. The moisture content increased significantly from 65.0% (P < 0.05) for unwashed minces to 69.3–74.1% after the second washing and to 76.2–79.7% after the third washing. Increasing moisture content with increased number of washed also was found in a previous study of surimi-like material made from spent hen meat. Uddin et al. (2006) reported that surimi may contain a moisture content ranging from 73 to 80% and that 78% moisture content is the most preferable.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of unwashed and washed meat

| Washing treatment | Moisture (%) | Fat (%) | Protein (%) | Yield (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwashed | 65.0 ± 0.20a | 22.8 ± 0.13e | 11.3 ± 0.14d | 100 | |

| Tap water | 2nd | 69.3 ± 1.45b | 13.7 ± 0.31d | 11.0 ± 0.05d | 42.4 |

| 3rd | 79.0 ± 0.04f | 5.8 ± 0.48a | 9.5 ± 0.21c | 26.2 | |

| NaCl | 2nd | 72.6 ± 2.25c | 11.1 ± 0.22c | 11.0 ± 0.13d | 33.1 |

| 3rd | 79.7 ± 0.40f | 4.9 ± 0.54a | 9.4 ± 0.02c | 24.1 | |

| NaHCO3 | 2nd | 72.8 ± 1.24c | 11.8 ± 0.04c | 11.1 ± 0.05d | 34.1 |

| 3rd | 76.2 ± 0.82de | 8.5 ± 0.08b | 8.0 ± 0.04a | 26.2 | |

| Sodium Phosphate buffer | 2nd | 74.1 ± 0.14cd | 10.6 ± 0.73c | 11.2 ± 0.18d | 35.4 |

| 3rd | 77.5 ± 1.53ef | 7.6 ± 0.09b | 8.8 ± 0.30b | 23.2 | |

Data are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations of duplicate samples. Different superscript letter in the same column indicate significant differences among samples

Fat is considered to be an undesirable component in surimi. In this study, the fat content decreased from 22.8% for unwashed minces to 10.6–13.7% after the second wash and to 5.8–8.5% after the third wash. Thus, the second and third washing resulted in 39.7–53.5% and 62.6–74.5% fat removal, respectively. Fat removal in this study was not as low as that for chicken surimi reported previously i.e. 1–3% fat content (Ensoy et al. 2004; Jin et al. 2007a). Relative to chicken, duck meat has a higher fat content, and it is rich with intramuscular fat and pigments, likely similar to red meat (Baéza 2006). Moreover, the grinding method used can affect fat content. Liang and Hultin (2003) reported that surimi-like material made from finely ground mechanically deboned meat had a higher fat content than coarsely ground mechanically deboned meat.

Concentration of myofibrillar proteins means that other proteins may be eliminated. In this study, protein content was rather constant: 11.3% for unwashed meat; 11.0–11.2% after the second wash; and decreased significantly to 8.0–9.5% (P < 0.05) after the third wash. Most of the proteins eliminated during surimi processing are sarcoplasmic proteins, which are water soluble and considered to be undesirable components; other eliminated proteins include the heme pigments and blood (Baxter and Skonberg 2008).

On meat yields percentage, these washing processes yielded a small amount of meat i.e. 33.1–42.4% after the second washing, which is similar to results for surimi-like material made from mutton washed four times (McCormick et al. 1993). Nonetheless, the third wash resulted in a lower yield of meat (~23.2–26.2%). Tap water resulted in higher yield by removing the fat and retaining the salt soluble protein, whereas the NaHCO3 had a close value of yield due to retaining more fat compared to tap water. NaCl and sodium phosphate buffer resulted in lower yield due to the loss of fat and some salt soluble proteins which are considered as solid components.

Fat removal after second wash ranged from 39.6-53.5%. During washing, the stirring of mixer in meat slurry gave some forces to separate the fats from the meat. Centrifugation in further step made obvious separation of fat from water and meat by the gap of molecular weight. Third washing removed the fats until 62.5-78.6%. This result is comparable to chicken broiler and spent hen surimi reported by Nowsad et al (Nowsad et al. 2000).

The recovered protein after third washing ranged from 71.1 to 84.2%. This result is much higher than spent duck surimi with acid-alkaline solubilization which recovered only 26.4–34.3% protein (Nurkhoeriyati et al. 2011). Two times washing by all solutions are not significantly different on the protein recovery. Tap water and NaCl resulted in highest protein recovery after third washing which is above 80%. NaHCO3 had the lowest protein recovery, about 70%. The lower protein recovery is might be due to the loss of some amount of salt soluble proteins together with the water soluble proteins and wash water during dewatering process. These results are higher compared to surimi-like material from mechanically deboned chicken meat done by Yang and Froning (Yang and Froning 1992), which had 51.2-58.8% protein recovery.

pH and WHC

Table 2 lists pH and WHC values of unwashed and washed meat. Unwashed duck meat had a pH of 6.5, which agrees with Kang et al. (2009) who stated that the pH of deboned meat typically is about 6.5. Each washing cycle significantly increased pH. Among the solutions, washing with tap water achieved the lowest pH gain, whereas washing with NaHCO3 resulted in the greatest gain (from 6.5 to 8.3 after the second wash and 8.4 after the third wash). This gain was due to the high pH of the NaHCO3 solution used. These results agreed with those of a previous description of chicken surimi processing (Nowsad et al. 2000; Yang and Froning 1992). The unwashed duck meat initially contained lactic acid as the result of post-rigor anaerobic glycolysis, which caused its low pH value. The washing processes reduced lactic acid and affected the incremental gain in pH (Jin et al. 2007b).

Table 2.

pH, WHC, breaking force, and gel strength of unwashed and washed meat

| Washing treatment | pH | WHC (g water/g protein) | Breaking force (g) | Gel strength (g mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwashed | 6.5 ± 0.04a | 3.3 ± 0.04a | 135.6 ± 7.96a | 1136.2 ± 28.96a | |

| Tap water | 2nd | 7.0 ± 0.00b | 4.6 ± 0.12b | 574.2 ± 11.28e | 6246.6 ± 221.26e |

| 3rd | 7.1 ± 0.01b | 4.9 ± 0.03b | 945.6 ± 0.40f | 9477.7 ± 99.26f | |

| NaCl | 2nd | 7.1 ± 0.13b | 4.9 ± 0.05b | 508.2 ± 3.54d | 5299.5 ± 392.54d |

| 3rd | 7.3 ± 0.06cd | 6.0 ± 0.05c | 615.0 ± 56.60e | 5998.8 ± 49.39e | |

| NaHCO3 | 2nd | 8.3 ± 0.05e | 8.6 ± 0.03e | 256.1 ± 14.73b | 2672 ± 20.27b |

| 3rd | 8.4 ± 0.03e | 12.5 ± 0.07f | 265.0 ± 32.92b | 2432.8 ± 203.10b | |

| Sodium Phosphate buffer | 2nd | 7.2 ± 0.02c | 5.8 ± 0.23c | 340.0 ± 28.58c | 3708.2 ± 270.11c |

| 3rd | 7.4 ± 0.04d | 8.1 ± 0.28d | 374.8 ± 15.06c | 3953.4 ± 65.66c | |

Data are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations of duplicate samples. Different superscript letter in the same column indicate significant differences among samples

The pH of meat influences its WHC. The results of this study revealed a positive significant correlation between pH and WHC (R2 = 0.802) at the 0.01 level. The acidic condition of the post-rigor meat brought actin (thin filaments) and myosin (thick filaments) near their isoelectric point, thus minimizing the space between filaments and minimizing the amount of free water that could be retained (Alvarado and McKee 2007).

The washing process also affected WHC significantly. Each washing solution increased the WHC to varying degrees. Washing with tap water had the smallest effect on WHC, and no significant increase occurred between the second and third washing. Washing with NaCl had a greater effect than tap water, resulting in WHC values 4.9 and 5.96 g water/g protein after the second and third washing, respectively. Washing with sodium phosphate buffer resulted in 5.8 g water/g protein after the second wash, and this value increased significantly to 8.1 g water/g protein after the third wash. Washing with NaHCO3 resulted in the highest increases in WHC: 8.6 and 12.5 g water/g protein after the second and third wash, respectively. The data show that WHC increased along with pH after each successive washing cycle.

Bertram et al. (2008) mentioned NaCl and phosphate were traditionally used as active water binding compounds. Toldrá explained (2003) chloride ions bind to the protein and exert repulsion force between filaments causing swelling on meat protein structure. Laack et al. (1998) reported that NaHCO3 is an effective ingredient for improving the WHC of meat. The increase in WHC observed herein is due partially to protein solubilization caused by the interaction between compounds in the washing solutions and meat proteins, which promotes the swelling of myofibrils (Bertram et al. 2008). Water holding properties of meat can be affected by any substance that influences spacing between actin and myosin or the ability of protein to bind exogenous water (Alvarado and McKee 2007). In this study, WHC was positively correlated with moisture content (R2 = 0.575) and negatively correlated with fat (R2 = −0.579) and protein (R2 = −0.717) content (significant at the 0.01 level).

Breaking force and gel strength

Breaking force and gel strength data are shown in Table 2. According to Hossain et al. (2011) and Dondero et al. (2002), when surimi is solubilized with salt and kept at around 35–40°C during setting, it forms an elastic gel. Further heating at >80°C forms a cooked gel of greater strength than one formed without setting.

In this study, unwashed meat had very low gel strength and breaking force. When compared with fish surimi as reported by Chiang et al. (2005) breaking force of unwashed duck meat is very low. In contrast, washing processes increased breaking force and gel strength significantly. Washing with tap water achieved the greatest improvement in breaking force and gel strength among the solutions tested: 574.2 g and 6246.6 g mm after the second wash and 945.6 g and 9477.7 g mm after the third wash, respectively. Sodium chloride increased breaking force and gel strength into 508.2 g and 5299.5 g mm after second washing, and 615 g and 5998.8 g mm after third washing. Significant differences in gel strength and breaking force were not detected between the second and third washing with NaHCO3 and sodium phosphate buffer. Furthermore, washing with NaHCO3 resulted in the lowest breaking force and gel strength among the solutions tested. These duck surimi-like materials washed using tap water, NaCl, and phosphate buffer resulted in higher breaking force compared with fish surimi which had breaking force around 300 g (Chiang et al. 2005).

Gel strength was positively correlated with moisture content (R2 = 0.657; significant at the 0.01 level) and negatively correlated with fat content (R2 = −0.675; significant at the 0.01 level) and protein content (R2 = −0.460; significant at the 0.05 level). Breaking force was positively correlated with moisture content (R2 = 0.535; significant at the 0.05 level) and negatively correlated with fat content (R2 = −0.585; significant at the 0.05 level).

Washing with NaHCO3 solution both tenderized meat and caused swelling of myofibrils, which is closely related to elevation of WHC and pH (Sheard and Tali 2004). Klinhom et al. (2009) reported a decrease in the shear force in bovine rumen viscera injected with NaHCO3 solution. Protein content also affects breaking force, in that higher protein concentration results in higher breaking force (Luo et al. 2006). Surimi-like material made by washing duck meat three times with tap water contained the highest protein content, whereas the meat washed three times with NaHCO3 contained the least.

Myoglobin content, lightness, and whiteness

Table 3 lists the myoglobin content and lightness and whiteness values of unwashed and washed meat. The myoglobin content of unwashed meat was 8.2 mg/gram, which is much higher than that of chicken thigh meat i.e. < 6 mg/gram (Kranen et al. 1999). Myoglobin concentration of meat varies extensively in every animal species and depends on muscle fiber type, exercise, sex, and diet. For example, poultry leg muscle contains more myoglobin than breast muscle (Vallejo-Cordoba et al. 2010). In this study, the second wash removed extensive amounts of myoglobin, leaving 2.9 mg/gram when washed with tap water and 1.0–1.1 mg/gram when washed with the other solutions. The third wash decreased the myoglobin content slightly to 2.4 mg/gram for tap water and 0.56–0.77 mg/gram for the other solutions.

Table 3.

Myoglobin content, lightness, and whiteness of unwashed and washed meat

| Washing treatment | Myoglobin (mg/g) | Lightness | Whiteness | Protein solubility (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwashed | 8.2 ± 0.01a | 60.9 ± 0.60a | 56.4 ± 0.02a | 38.8 ± 2.15a | |

| Tap water | 2nd | 2.9 ± 0.07b | 66.6 ± 0.18b | 62.5 ± 0.12b | 39.8 ± 2.07a |

| 3rd | 2.4 ± 0.04c | 74.5 ± 0.71c | 65.7 ± 0.83c | 59.1 ± 1.32c | |

| NaCl | 2nd | 1.0 ± 0.02d | 75.2 ± 0.02c | 66.3 ± 0.11c | 39.7 ± 1.76a |

| 3rd | 0.6 ± 0.03e | 84.3 ± 0.31d | 73.1 ± 0.06e | 59.7 ± 0.13c | |

| NaHCO3 | 2nd | 1.1 ± 0.01d | 84.0 ± 0.32d | 71.8 ± 0.02d | 40.3 ± 2.12a |

| 3rd | 0.8 ± 0.01e | 87.0 ± 0.07ef | 74.1 ± 0.52f | 52.4 ± 0.28b | |

| Sodium Phosphate buffer | 2nd | 1.1 ± 0.06d | 86.4 ± 0.24e | 74.2 ± 0.33f | 38.9 ± 1.57a |

| 3rd | 0.56 ± 0.01e | 87.5 ± 0.66f | 75.1 ± 0.36g | 51.8 ± 1.79b | |

Data are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations of duplicate samples. Different superscript letter in the same column indicate significant differences among samples

Because myoglobin is a sarcoplasmic protein, it is soluble in water and thus much of it is extracted during the washing process (Piyadhammaviboon and Yongsawatdigul 2010). Tap water removed less myoglobin than the salt-containing solutions (NaCl, NaHCO3, and sodium phosphate buffer). Salt compounds in washing solutions may weaken and break the bonds between muscle and myoglobin, thereby releasing more myoglobin, which then is solubilized in water and removed through washing (Chaijan et al. 2004).

Myoglobin content was negatively correlated with pH (R2 = −0.677), lightness (R2 = −0.839), and whiteness (R2 = −0.863), all three of these were significant at the 0.01 level. The loss of myoglobin during washing resulted in brighter colored surimi; lightness and whiteness are particularly important quality attributes of surimi (Jin et al. 2007a). More washing cycles have been shown to produce surimi with a greater whiteness value (Jin et al. 2009). Washing with NaCl, NaHCO3, and sodium phosphate buffer resulted in greater improvement in lightness and whiteness compared to washing with tap water. This result agrees with that of a previous description of chicken surimi (Yang and Froning 1992).

Higher improvements of color properties were achieved by other washing solutions. Second washing with NaCl resulted in 24% higher in lightness and 17% in whiteness. NaHCO3 and sodium phosphate buffer brought the greatest improvement in color properties that reached more than 40% in lightness and 30% in whiteness. These results agreed with that of a previous description of chicken surimi (Ensoy et al. 2004).

Protein solubility

Protein solubility in 3% NaCl solution of unwashed and washed meat is shown in Table 3. There is no significant difference in protein solubility between unwashed meat and second-washed meat which were ranging from 38.8-40.3%. On the other side, three times washing successfully increased the protein solubility significantly i.e. 59.1, 59.7, 52.4, and 51.8 for washed meat using tap water, NaCl, NaHCO3, and sodium phosphate respectively.

Increase in protein solubility in 3% NaCl indicated the myofibrillar proteins were concentrated. According to Hultin et al. (2005) salt soluble proteins are defined as proteins those are soluble in salt concentrations greater than 0.3M, with or without pH adjustment or the presence of components such as magnesium ion and ATP. This 3% NaCl solution used in protein solubility analysis was equal to about 0.5M.

During washing processes, NaHCO3 and sodium phosphate buffer caused partially solubilization of myofibrillar proteins (Bertram et al. 2008). However, the solubilized myofibrillar proteins were washed away through dewatering by centrifugation. Therefore, their protein solubility is lower than tap water-washed and NaCl solution-washed meat. Protein solubility is positively correlated with gel hardness, chewiness, cohesiveness (R2 = 0.743, 602, and 625 respectively; significant at the 0.01 level), gel strength and breaking force (R2 = 526 and 575 respectively; significant at the 0.05 level).

Texture profile analysis of cooked surimi gels

Results of the texture profile analysis of cooked gels made from unwashed and washed meats are shown in Table 4. Meat washed three times with tap water or three times with NaCl had the highest hardness values, and these values were not significantly different. All washed meat had higher values of chewiness and cohesiveness than unwashed meat, and meat washed with tap water had the highest values for chewiness and cohesiveness among the washing solutions tested. Because washing made the hardness values high, the values for chewiness were high as well. These texture profiles of washed meat were mostly higher compared to the value of gel strength analysis results. This result had been confirmed by Lee and Chung’s work (1989) on fish surimi made from several species. Hardness, chewiness and cohesiveness had positive correlation with gel strength (R2 = 0.716, 0.663, and 0.778 respectively, significant at the 0.01 level).

Table 4.

Texture profile analysis of unwashed and washed meat

| Washing Treatment | Hardness (g) | Springiness | Chewiness (g) | Cohesiveness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwashed | 2313 ± 8.8a | 0.69 ± 0.01d | 222.9 ± 18.8a | 0.14 ± 0.01a | |

| Tap water | 2nd washing | 7234.8 ± 166.9cd | 0.53 ± 0.00b | 717.6 ± 18.0cd | 0.19 ± 0.00b |

| 3rd washing | 9224.2 ± 216.4f | 0.41 ± 0.05a | 949.2 ± 88.4f | 0.25 ± 0.00c | |

| NaCl | 2nd washing | 7183 ± 154.7cd | 0.40 ± 0.04a | 509.5 ± 20.6b | 0.18 ± 0.01b |

| 3rd washing | 9703.2 ± 565.4f | 0.44 ± 0.00a | 837.7 ± 26.6ef | 0.20 ± 0.01b | |

| NaHCO3 | 2nd washing | 5884.5 ± 207.0b | 0.59 ± 0.01c | 617.1 ± 33.5bc | 0.18 ± 0.01b |

| 3rd washing | 7786.7 ± 112.6d | 0.44 ± 0.04a | 664.8 ± 52.7c | 0.19 ± 0.02b | |

| Sodium Phosphate buffer | 2nd washing | 6762.7 ± 289.0c | 0.58 ± 0.04bc | 827.6 ± 47.0de | 0.19 ± 0.02b |

| 3rd washing | 8414.5 ± 347.5e | 0.53 ± 0.01b | 850.0 ± 79.3ef | 0.20 ± 0.03b | |

Data are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations of duplicate samples. Different superscript letter in the same column indicate significant differences among samples

The springiness values of washed meat were lower than those of unwashed meat, which means that unwashed meat maintained the food’s height after the first compression better than washed meat. This study obtained higher improvement on texture profiles compared to the surimi-like materials made with acid and alkaline solubilization methods (Nurkhoeriyati et al. 2011; James and DeWitt 2004). According to Lee and Chung (1989), this texture profile analysis with compression method is more useful in assessing the overall binding (cohesive) properties of surimi, while the penetration test, which obtained the value of gel strength and breaking force, is better for assessing density and compactness. Park and Lin (2005) stated among the properties related to surimi, gel strength is the primary interest in surimi production and trade.

Microstructure

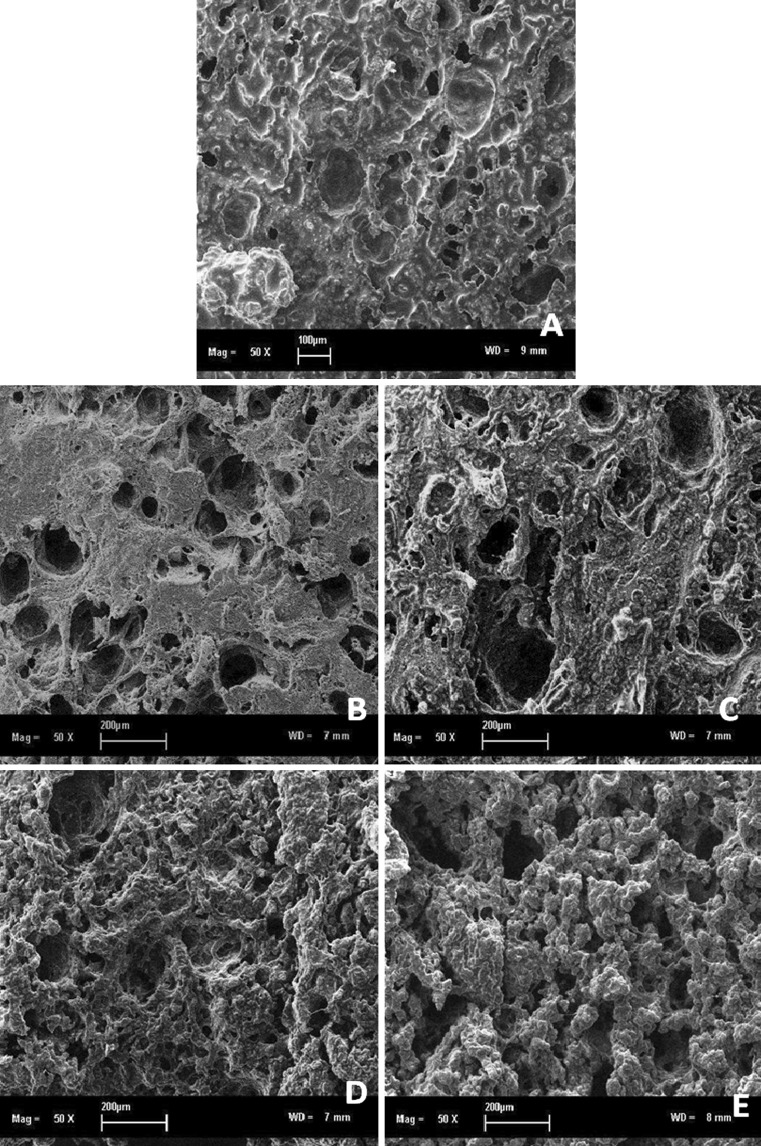

Cooked gels from unwashed meat had a coarse and porous structure due to protein aggregation (Fig. 1). Meat proteins connected and made fibrous matrix while gelation process occurred. Scattered pores with different size and depth described the remaining trapped water in the cooked gels. Water holding capacity of meat is related to the microstructure. The water is trapped within the meat by capillary action which is generated by small pores or capillaries. During processing and heating, meat proteins were rearranged and aggregated which resulted in a three-dimensional lattice protein formation (Han et al. 2009). A bright, whitish color and wet-look surface was resulted from intact amount of fat in the cooked gel.

Fig. 1.

Microstructure of cooked gels from a unwashed, b tap water-washed, c NaCl-washed, d NaHCO3-washed and e sodium phosphate buffer-washed meat (magnification 50×)

Microstructure of tap water-washed meat cooked gels showed some concentrated dense area which was formed by myofibrillar proteins gel networks and resulted in improved breaking force and gel strength. Some larger size, deep and localized pores were produced as influences of encapsulated capillary water (Yang and Froning 1992). This represents a condition of higher water holding capacity of meat. Whitish surface area was diminished as the fat content of tap water-washed meat was reduced. Smaller sizes of fat globules are still remained after the washing processes. Cooked gels from NaCl solution-washed meat showed similar dense structures with tap water-washed meat. The larger and deeper pores appeared as an outcome of held water within the cooked gel networks. Upon heating during gelation process, proteins were denatured and hydrophobic surfaces were exposed which led protein to release the water (Bertram et al. 2008). Only few amounts of fat globules are left on the gel surface.

SEM observation for cooked gels of washed meat with NaHCO3 showed abundant pores of coarse structure with numerous air pockets. It can be related to their high water holding capacity which can immobilize water. Furthermore, carbon dioxide was formed from bicarbonate during heating hence it made the air pockets (Sultana et al. 2008). This porous structure of cooked gels effected lower gel strength and breaking force.

Cooked gels of washed meat with sodium phosphate buffer showed similar structure, coarse and abundant pores as a result of high water holding capacity then caused the lower gel strength and breaking force on textural properties. NaHCO3 and sodium phosphate buffer solutions-washed meat contain more widely distributed pores on the gel structures rather than tap water and NaCl solutions-washed meat. Within the meat protein structures, water molecules are bound by non-covalent bond such as hydrogen bonds. Every single molecule of proteins has various electric dipoles which easily forms hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Therefore, the existing of bicarbonate or phosphate in meat proteins would expand the exposed surfaces of macromolecules which resulted in more water molecules held within meat protein structure (Bertram et al. 2008).

Conclusion

Functional properties of mechanically deboned duck meat can be improved by processing it into surimi-like material. Washing the meat three times was sufficient to remove the fats, maintain the proteins, and obtain high values of functional and textural properties. Among the washing solutions tested, washing with tap water achieved the highest gel strength, hardness, cohesiveness, and chewiness; moderate increases in WHC, pH, , protein solubility, lightness, and whiteness; and left a small amount of fat. These results show that surimi-like material from mechanically deboned duck meat can be used as an ingredient in processed poultry products.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the support given by the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM). This research was conducted with aid from a research grant provided by the MALAYAN SUGAR MANUFACTURING COMPANY BERHAD.

References

- Ali MS, Kang G-H, Yang H-S, Jeong J-Y, Hwang Y-H, Park G-B, Joo S-T. A comparison of meat characteristics between duck and chicken breast. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2007;20:1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado C, Mckee S. Marination to improve functional properties and safety of poultry meat. J Appl Poult Res. 2007;16:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists. 17. Gaithersburg: AOAC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Babji AS, Gna SK. Changes in colour, pH, WHC, protein extraction and gel strength during processing of chicken surimi (ayami) ASEAN Food J. 1994;9:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Baéza E (2006) Effects of Genotype, Age and Nutrition on Intramuscular Lipids and Meat Quality. Symposium COA/INRA Scientific Cooperation in Agriculture. November 7–10, Tainan, Taiwan, Republic of China

- Balange A, Benjakul S. Enhancement of gel strength of bigeye snapper (Priacanthus tayenus) surimi using oxidised phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2009;113:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter SR, Skonberg DI. Gelation properties of previously cooked minced meat from Jonah crab (Cancer borealis) as affected by washing treatment and salt concentration. Food Chem. 2008;109:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram HC, Meyer RL, Wu Z, Zhou X, Andersen HJ. Water distribution and microstructure in enhanced pork. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:7201–7207. doi: 10.1021/jf8007426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya D, Sinhamahapatra M, Biswas S. Preparation of sausage from spent duck-an acceptability study. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2007;42:24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01194.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Chakraborty A, Sarkar S. Comparison among the qualities of patties prepared from chicken broiler, spent hen and duck meats. J Poult Sci. 2006;43:180–186. doi: 10.2141/jpsa.43.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaijan M, Benjakul S, Visessanguan W, Faustman C. Characteristics and gel properties of muscles from sardine (Sardinella gibbosa) and mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) caught in Thailand. Food Res Int. 2004;37:1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang B-H, Chou S-T, Hsu C-K. Yam affects the antioxidative and gel-forming properties of surimi gels. J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:2385–2390. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande SD. Effect of soaking time and temperature on textural properties of soybean. J Texture Stud. 2001;32:343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2001.tb01241.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dondero M, Curotto E, Figueroa V. Transglutaminase effects on gelation of Jack Mackerel Surimi (Trachurus murphyi) Food Sci Tech Int. 2002;8:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ensoy Ü, Kolsarici N, Candoğan K. Quality characteristics of spent layer surimi during frozen storage. Eur Food Res Technol. 2004;219:14–19. doi: 10.1007/s00217-004-0886-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faostat (2009) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistical Databases-Agriculture Production-Live Stock Primary-Duck Meat Production. http://faostat.fao.org/site/569/default.aspx#ancor. Accessed 11.11.09.

- Froning GW, Mckee SR. Mechanical separation of poultry meat and its use in products. In: Sams AR, editor. Poultry meat processing. Washington DC: CRC; 2001. pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Zhang Y, Fei Y, Xu X, Zhou G. Effect of microbial transglutaminase on NMR relaxometry and microstructure of pork myofibrillar protein gel. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;228:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s00217-008-0976-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JE, Desmond EM, Troy DJ, Buckley DJ, Mehra R. The effect of whey protein-enriched fractions on the physical and sensory properties of frankfurters. Meat Sci. 2005;71:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MI, Morioka K, Shikha FH, Itoh Y. Effect of preheating temperature on the microstructure of walleye pollack surimi gels under the inhibition of the polymerisation and degradation of myosin heavy chain. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91(2):247–52. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huda N, Lin OJ, Ping YC, Nurkhoeriyati T. Effect of chicken and duck meat ratio on the properties of sausage. Int J Poult Sci. 2010;9:550–555. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2010.550.555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huda N, Putra AA, Ahmad R. Potential application of duck meat for development of processed meat products. Curr Res Poult Sci. 2011;1(1):1–11. doi: 10.3923/crpsaj.2011.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hultin HO, Kristinsson HG, Lanier TC, Park JW. Process for recovery of functional proteins by pH shifts. In: Park JW, editor. Surimi and surimi seafood. 2. Boca Raton: CRC; 2005. pp. 107–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail I, Huda N, Ariffin F, Ismail N. Effects of washing on the functional properties of duck meat. Int J Poult Sci. 2010;9:2010. [Google Scholar]

- James J, Dewitt C. Gel attributes of beef heart when treated by acid solubilization isoelectric precipitation. J Food Sci. 2004;69:C473–C479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb10991.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S-K, Kima I-S, Kima S-J, Jeong K-J, Choi Y-J, Hur S-J. Effect of muscle type and washing times on physico-chemical characteristics and qualities of surimi. J Food Eng. 2007;81:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SK, Kim IS, Jung HJ, Kim DH, Choi YJ, Hur SJ. The development of sausage including meat from spent laying hen surimi. Poult Sci. 2007;86:2676–2684. doi: 10.3382/ps.2006-00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SK, Kim IS, Choi YJ, Kim BG, Hur SJ. The development of imitation crab stick containing chicken breast surimi. LWT-Food Sci Tech. 2009;42:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang I, Skaar GR, WNG Barron I, Painter CJ, Colby JD, Salman HK (2009) Washed deboned meat having high protein recovery. In Patent, U. S. (Ed.) 7569245. USA, Kraft Foods Holdings, Inc

- Karayannakidis PD, Zotos A, Petridis D, Taylor KDA. The effect of washing, microbial transglutaminase, salts and starch addition on the functional Properties of Sardine (Sardina pilchardus) kamaboko gels. Food Sci Technol Int. 2008;14:167–177. doi: 10.1177/1082013208092816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klinhom P, Klinhom J, Halee A, Methawiwat S. Effect of calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate inject solutions on tenderness and organoleptic properties of bovine rumen viscera. J Food Technol. 2009;7:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kranen RW, Vankuppevelt TH, Goedhart HA, Veerkamp CH, Lambooy E, Veerkamp JH. Hemoglobin and myoglobin content in muscles of broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 1999;78:467–476. doi: 10.1093/ps/78.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laack RLJMV, Kauffman RG, Pospiech E, Greaser M, Lee S, Solomon MB. A research note the effects of prerigor sodium bicarbonate perfusion on the quality of porcine M. semimembranosus. J Muscle Foods. 1998;9:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.1998.tb00653.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Chung KH. Analysis of surimi gel properties by compression and penetration tests. J Texture Stud. 1989;20:363–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1989.tb00446.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Hultin H. Functional protein isolates from mechanically deboned turkey by alkaline solubilization with isoelectric precipitation. J Muscle Foods. 2003;14:195–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.2003.tb00700.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Shen H, Pan D. Gel-forming ability of surimi from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus): influence of heat treatment and soy protein isolate. J Sci Food Agric. 2006;86:687–693. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick RJ, Bugren S, Field RA, Rule DC, Busboom JR. Surimi-like products from mutton. J Food Sci. 1993;58:497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1993.tb04309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montero P, Pardo MV, Gómez-Guillén MC, Borderias J. Chemical and functional properties of sardine (Sardina pilchardus W.) dark and light muscle. Effect of washing on mince quality. Food Sci Technol Int. 1999;5:139–147. doi: 10.1177/108201329900500203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowsad AAKM, Kanoh S, Niwa E. Thermal gelation characteristics of breast and thigh muscles of spent hen and broiler and their surimi. Meat Sci. 2000;54:169–175. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(99)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkhoeriyati T, Huda N, Ahmad R. Surimi-like material: challenges and prospects. Int Food Res J. 2010;17:509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Nurkhoeriyati T, Huda N, Ahmad R. Gelation properties of spent duck meat surimi-like material produced using acid–alkaline solubilization methods. J Food Sci. 2011;76:S48–S55. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkececi R, Karakaya M, Yilmaz M, Saricoban C, Ockerman H. The effect of carcass part and packaging method on the storage stability of mechanically deboned chicken meat. J Muscle Foods. 2008;19:288–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.2008.00118.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JW. Code of practice for frozen surimi (Appendix) In: Park JW, editor. Surimi and surimi seafood. 2. Boca Raton: CRC; 2005. pp. 869–886. [Google Scholar]

- Park JW, Lin TMJ. Surimi: manufacturing and evaluation. In: Park JW, editor. Surimi and surimi seafood. 2. Boca Raton: CRC; 2005. pp. 33–98. [Google Scholar]

- Piyadhammaviboon P, Yongsawatdigul J. Proteinase inhibitory activity of sarcoplasmic proteins from threadfin bream (Nemipterus spp.) J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:291–298. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan K, Huda N, Ahmad R. Duck meat utilization and the application of surimi-like material in further processed meat products. J Biol Sci. 2010;10:405–410. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2010.405.410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard PR, Tali A. Injection of salt, tripolyphosphate and bicarbonate marinade solutions to improve the yield and tenderness of cooked pork loin. Meat Sci. 2004;68:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth A, O'neill E. Heat-induced gelation properties of surimi from mechanically separated chicken. J Food Sci. 1997;62:326–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1997.tb03994.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza CFVD, Venzke JG, Flôres SH, Ayub MAZ. Nutritional effects of mechanically deboned chicken meat and soybean proteins cross-linking by microbial transglutaminase. Food Sci Technol Int. 2009;15:337–344. doi: 10.1177/1082013209346369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stangierski J, Kijowski J. Optimization of conditions for myofibril preparation from mechanically recovered chicken meat. Nahrung. 2000;44:333–338. doi: 10.1002/1521-3803(20001001)44:5<333::AID-FOOD333>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangierski J, Zabielski J, Kijowski J. Enzymatic modification of selected functional properties of myofibril preparation obtained from mechanically recovered poultry meat. Eur Food Res Technol. 2007;226:233–237. doi: 10.1007/s00217-006-0531-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana A, Nakanishi A, Roy B, Mizunoya W, Tatsumi R, Ito T, Tabata S, Rashid H, Katayama S, Ikeuchi Y. Quality improvement of frozen and chilled beef biceps femoris with the application of salt-bicarbonate solution. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2008;21:903–911. [Google Scholar]

- Tai C, Tai J-JL. Future prospects of duck production in Asia. J Poult Sci. 2001;38:99–112. doi: 10.2141/jpsa.38.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toldrá F. Muscle Foods: water, structure and functionality. Food Sci Technol Int. 2003;9:173–177. doi: 10.1177/1082013203035048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Okazaki E, Fukushima H, Turza S, Yumiko Y, Fukuda Y. Nondestructive determination of water and protein in surimi by near-infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2006;96:491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo-Cordoba B, Rodríguez-Ramírez R, González-Córdova AF. Capillary electrophoresis for bovine and ostrich meat characterisation. Food Chem. 2010;120:304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal V, Chawla S, Nair P. Spray dried protein powder from threadfin bream: preparation, properties and comparison with FPC type B. J Muscle Foods. 1996;7:55–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.1996.tb00587.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TS, Froning GW. Selected washing processes affect thermal gelation properties and microstructure of mechanically deboned chicken meat. J Food Sci. 1992;57:325–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1992.tb05486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]