Abstract

Hemolytic strains of Aeromonas spp. from fish and fishery products were detected by multiplex PCR. The selected primers for the amplification of segments of ahh1, asa1 and 16S rRNA gene yielded products with the size of 130 bp, 249 bp and 356 bp, respectively. This assay was found to be highly sensitive, as it could detect 7 and 9 cells of Aeromonas hydrophila and A. sobria with a detection limit of 1 pg of pure genomic DNA. The assay, when screened for 73 commercial fish and fishery product samples consisting of freshwater, marine fish and shellfish, showed 56 % positive for Aeromonas spp., 16 % for Aeromonas hydrophila and 13 % for A. sobria. This assay provides specific and reliable results and can be a powerful tool for the simultaneous detection of hemolytic strains of A. hydrophila A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp. from fish and fishery products.

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, Species-specific detection, Hemolytic strains, Fish and fishery products, Multiplex PCR

Introduction

Aeromonads are a group of mesophilic motile and psychrophilic non-motile, gram-negative rod shaped, oxidase-positive, facultative anaerobic microorganisms belonging to the family Aeromonadaceae (Monfort and Baleux 1990). Aeromonas currently has the status of an important emerging food-borne pathogen, primarily because of its ability to grow at cold temperatures (Kirov 2001). Varieties of foods such as raw, cooked and processed foods, also those held at refrigeration temperature, under modified atmosphere and under modified growing conditions including seafood have been shown to harbour motile Aeromonads (Pin et al. 1996; Devlieghere et al. 2000). Aeromonads have been detected in dairy products (4 %), vegetables (26–41 %), meats and poultry (3–70 %), with the largest numbers recorded from shellfish (31 %) and fish (72 %) (Janda and Abbott 2010). Aeromonas hydrophila (DNA hybridization group, HG1), and Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria (HG8) (otherwise known as A. sobria) are the most common species belonging to this genus, often encountered in fish and fishery products (Rahman et al. 2002; Vivekanandhan et al. 2005). Aeromonas spp. grow rapidly during iced storage of freshwater fishes, with more than a third of the population belonging to the species A. hydrophila and A. sobria (Gonzalez et al. 2001). The distribution of Aeromonas hydrophila in marine ecosystem including marine fish and retail seafood outlets is also well known and this organism is found to be normal flora in a variety of fish (Yogananth et al. 2009).

A. hydrophila and A. sobria are often found in association with hemorrhagic septicemia in cold-blooded animals including fish, reptiles, and amphibians (Janda and Abbott 2010). However, these organisms have also been implicated as primary pathogens in cases of acute diarrheal disease in immune-competent humans of all age groups (Aggar et al. 1985; Chopra and Houston 1999). A number of epidemiological surveys have shown that A. hydrophila (HG1), A. caviae (HG4) and A. sobria (HG8) are the most common species associated with human intestinal diseases (Borrell et al. 1997). Hemolytic uremic syndrome, a life-threatening condition normally associated with infections due to Escherichia coli O157: H7, has also been associated with A. hydrophila infection (Bogdanovic et al. 1991; Janda and Kokka 1991; Robson et al. 1992) and a cytotoxin with homology to Shiga toxin 1 has been identified in both the A. hydrophila and A. caviae (Haque et al. 1996). According to Kirov (2001), the majority of aeromonads associated with gastroenteritis belong to A. sobria (HG 8), A. hydrophila (HG1 and HG3), A. caviae (HG4), and to a lesser extent A. veronii biovar veronii (HG 8/10), A. trota (HG13), and A. jandaei (HG9). Virulence of Aeromonas spp. is multifactorial and incompletely understood (Pablos et al. 2009). A number of virulence factors derived from A. hydrophila and A. sobria have been examined in an effort to explain the pathogenesis of infections due to these organisms. Toxins with hemolytic, cytotoxic and enterotoxic activities have been described in many Aeromonas spp. (Bin Kingombe et al. 1999; Gonzalez-Rodriguez et al. 2002; Rahman et al. 2002). Nacescu et al. (1992) postulated a correlation between the pathogenic potential and the hemolytic activity of Aeromonas spp. A majority of the A. hydrophila and A. sobria isolates were highly hemolytic, whereas only 11 % of the A. caviae isolates were capable of lysing sheep erythrocytes (Nakano et al. 1990). Two hemolytic toxins have been described in A. hydrophila: the ahh1 hemolysin (Hirono and Aoki 1991) and aer aerolysin (Howard et al. 1987). Most Aeromonas hemolysins described to date are related to one of these two toxins and are reasonable predictors of human diarrhoeal disease in both the A. hydrophila and A. sobria (Heuzenroeder et al. 1999).

There are several conventional as well as rapid systems including PCR that have been tried for the detection of seafood borne pathogens (Kumar et al. 2006; Jeyasekaran et al. 2011; Raj et al. 2011). Although Aeromonas spp. has recently received increasing attention as an agent of food-borne diarrhoeal diseases in healthy people (Janda and Abbott 2010), the PCR has been mostly used for the characterization of isolates either for their virulence properties or for the phylogenetic positions (Yanez et al. 2003; Bin Kingombe et al. 2010; Fontes et al. 2011). In this study, hemolytic strains of A. hydrophila and A. sobria along with other Aeromonas spp. from fish and fishery products were detected by a MPCR assay targeting the amplification of ahh1, asa1 and 16S rRNA genes, respectively.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains, media, and reagents

Type cultures of Aeromonas used in this work included Aeromonas hydrophila (ATCC 7966), Aeromonas sobria (MTCC 1608), A. caviae (MTCC 7725) and Aeromonas liquefaciens (MTCC 2654). Other bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella typhi (ATCC 122235), Salmonella paratyphi A (MTCC 735), Vibrio cholerae (NICED 16582), and some isolates of Vibrio spp. viz. V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. alginolyticus obtained from our pathology laboratory were used to check the specificity of the assay. Media and their ingredients were purchased from Hi-Media Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai, India. Molecular grade water (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Gottingen, Germany) was used for the preparation of buffers and reagents.

Bacterial DNA extraction

For the extraction of DNA, bacterial type cultures were grown on trypticase soy broth (TSB) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h to obtain young culture prior to the extraction of genomic DNA. The genomic DNA from bacterial cells was extracted following guanidine hydrochloride method according to Haldar et al. (2005) with some modifications. One milliliter of the young cell suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and the cell pellet was mixed with 600 μl of guanidine hydrochloride buffer (pH 8.0), incubated at room temperature for 30 min and again centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. From that, 500 μl of the supernatant was transferred to another tube and mixed with 100 % ice cold ethanol and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 95 % and 90 % ethanol, respectively followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then re-suspended in 50 μl of molecular grade water, quantified in a Biophotometer (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) and then stored at −20 °C to be further used as PCR template.

Primers

Three sets of primers belonging to genus and species specific genes of Aeromonas were selected for the study. All the primer sequences were synthesized by Ocimum Biosolutions Inc., Indianapolis, USA. The oligonucleotide primer sequences, target genes, specificity and their expected product sizes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in the multiplex PCR assay for Aeromonas spp

| Primer pair | Primer sequences (5′ to 3′) |

Target genes | Specificity | Product size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A16S | F- GGG AGT GCC TTC GGG AAT CAG A R- TCA CCG CAA CAT TCT GAT TTG |

16S rRNA | Aeromonas spp. | 356 | Wang et al. (2003) |

| ASA1 | F- TAA AGG GAA ATA ATG ACG GCG R- GGC TGT AGG TAT CGG TTT TCG |

asa 1 | A. sobria | 249 | Wang et al. (2003) |

| AHH1 | F- GCC GAG CGC CCA GAA GGT GAG TT R- GAG CGG CTG GAT GCG GTT GT |

ahh 1 | A. hydrophila | 130 | Wang et al. (2003) |

F forward; R reverse

Optimization of multiplex PCR

Multiplex PCR for the simultaneous detection of Aeromonas spp., A. hydrophila and A. sobria in a single reaction was optimized by performing PCR at different annealing temperatures from 57 °C to 61 °C for 60 s by targeting 16S rRNA, ahh1 and asa1 genes, respectively in a Gradient Master Cycler (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). All the PCR mixtures were handled in the Bio-Safety Cabinet Type II (Clean Air Systems, Chennai, India). The amplification was done with 50 μl of reaction mixture containing template DNA of A. hydrophila and A. sobria, 10X PCR buffer (100 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 % gelatin), 100 mM of each dNTP, 30 pmol of each forward and reverse primers and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The optimization of MPCR conditions consisted of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min., followed by denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s; annealing temperatures ranging from 57 °C to 60 °C for 60 s; extension at 72 °C for 90 s for 45 cycles; and final extension at 72 °C for 3 min.

Gel electrophoresis

The PCR products were run on 2 % agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml) in Tris Acetate EDTA buffer (TAE, pH 8.4) using Submarine Electrophoresis System (GE HealthCare Bio-Science Ltd., HongKong) and observed under UV Transilluminator using Gel Documentation System (Alpha Innotech, California, USA). The products were identified in comparison with the 100 bp DNA ladder (Real Biotech Corporation, Ohio, USA).

Specificity of multiplex PCR

To test for the specificity of this assay towards Aeromonas, the multiplex PCR was also performed with the non-Aeromonas species such as Salmonella typhi, Salmonella paratyphi A, Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, and V. alginolyticus.

Sensitivity of multiplex PCR

Sensitivity of the multiplex PCR was performed using A. hydrophila and A. sobria to evaluate the minimal cells as well as genomic DNA required for their detection. To determine the minimal cell detection limit, fish tissue homogenate, 100 g, was pasteurized at 100 °C for 3 min and then divided into four lots of 25 g each in sterile petriplates. Aliquots of 100 μl of tenfold serial dilution (10−6 to 10−8) of overnight grown cultures of A. hydrophila and A. sobria were inoculated into first three lots of the homogenate. The fourth uninoculated lot homogenate was treated as control. The initial count of cells was determined by plating, 100 μl of aliquot from each dilution on Aeromonas starch DNA agar base (ASDAB) plates and incubating at 37 °C for 24 h. The homogenate containing inocula of A. hydrophila and A. sobria was enriched with 225 ml buffered peptone water and incubated at 37 °C. Immediately after inoculation and after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h of enrichment, 1.5 ml enriched sample was used to extract the genomic DNA and MPCR was performed as described earlier. To evaluate the genomic DNA sensitivity, DNA of A. hydrophila and A. sobria were extracted using guanidine hydrochloride and diluted with DNA-free water to a concentration ranging from 1,000 pg to 10 fg and subjected to same MPCR assay as described earlier.

Validation of multiplex PCR

Seventy three samples of fresh fish including 23 freshwater fish, 20 marine fish, 16 fresh shrimps and 14 fresh squids were screened for the presence of Aeromonas spp. by the developed multiplex PCR assay. The samples were procured from the local fish markets, Tuticorin, India and brought to the laboratory in iced condition and used for analysis within 3 h. For the isolation of Aeromonas spp., 25 g of each sample was enriched in 225 ml of buffered peptone water (pH 7.0) for 18 to 24 h at 37 °C. Enrichment was done to recover even single Aeromonas spp. present in the sample. The enriched sample was then serially diluted, spread plated onto ASDAB plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18 to 24 h to obtain yellow colored colonies. A total of 162 representative colonies from the ASDAB plates were picked up, purified and used for the analysis by MPCR. The isolates of Aeromonas, which showed PCR positive, were also confirmed to the species level by Aerokey II (Carnahan et al. 1991).

Results and discussion

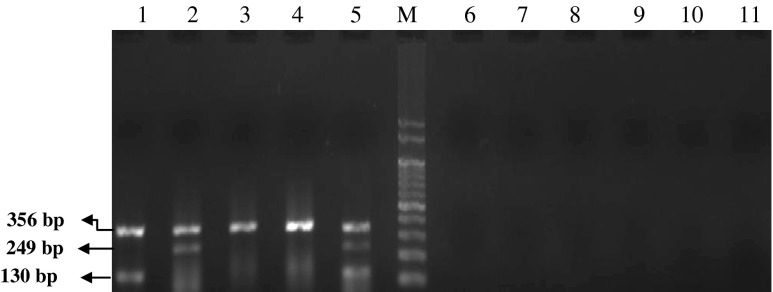

In the developed multiplex PCR assay, the 16S rRNA and asa1 genes were amplified only in A. sobria and 16S RNA and ahh1 genes were amplified only in A. hydrophila and 16S rRNA gene was alone amplified in A. liquefaciens (Fig. 1). The specificity of the multiplex PCR assay tested by using the DNA extracted from non-Aeromonas species such as Salmonella typhi, Salmonella paratyphi A, Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, V. alginolyticus showed that the assay did not amplify 16S rRNA, asa1 and ahh1 genes in any of the non-Aeromonas species tested (Fig. 2). The development of multiplex PCR assay for Aeromonas spp. has been mainly focused by the earlier authors to identify the Aeromonas spp. alone by the presence of different genes as well as to identify A. hydrophila using the set of genes unique for A. hydrophila. Wang et al. (2003) developed a MPCR using aerA and ahh1 gene specific for A. hydrophila and asa1 specific for A. sobria from clinical isolates. Bin Kingombe et al. (2010) reported a MPCR assay to detect the presence of three enterotoxin genes in Aeromonas spp. which include cytotoxic (act), heat-liable (alt) and heat-stable enterotoxin gene (ast), for the detection of Aeromonas spp in food. Choresca et al. (2010) developed a MPCR assay to detect A. hydrophila by amplification of 130 bp fragment of hemolysin and 309 bp fragment of aerolysin gene from diseased Clarius spp. Balakrishna et al. (2010) reported another MPCR assay for the detection of A. hydrophila by amplification of hemolysin (hlyA), aerolysin (aerA), glycerophospholipid-cholestrol acyl transferase (GCAT) along with 16S rRNA gene. Pinto et al. (2012) developed a MPCR method for Aeromonas spp using hlyA, aerA, alt and ast genes encoding hemolysin A, aerolysin, aeromonas labile temperature cytotonic enterotoxin and aeromonas stable temperature cytotonic enterotoxin, respectively. As most of the developed MPCR assays focused on the detection of either Aeromonas spp. or A. hydrophila, the present assay was targeted for the amplification of three sets of genes for simultaneous detection of A. hydrophila and A. sobria along with other Aeromonas spp. (Fig. 1). The 16S RNA primer was used to amplify a 356 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene which is conserved for the genus Aeromonas for confirming the presence of Aeromonas spp. Similarly, for the specific detection of A. hydrophila and A. sobria, the primers were selected for the virulence associated genes, ahh1 and asa1, respectively having hemolytic properties.

Fig. 1.

Detection of A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp by uniplex and multiplex PCR. Lane 1- A. hydrophila; Lane 2- A. sobria; Lane 3- Aeromonas spp.; Lane 4- multiplex for A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp.; Lane M-100 bp DNA marker

Fig. 2.

Specificity of MPCR assay for the detection of A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp. Lane 1- A. hydrophila; Lane 2- A. sobria; Lane 3- A. caviae; Lane 4- A. liquefaciens; Lane 5- A. hydrophila and A. sobria; Lane 6- Salmonella typhi; Lane 7- S. paratyphi A; Lane 8- Vibrio cholerae; Lane 9- V. parahaemolyticus; Lane 10- V. vulnificus; Lane 11- V. alginolyticus; Lane M-100 bp DNA marker

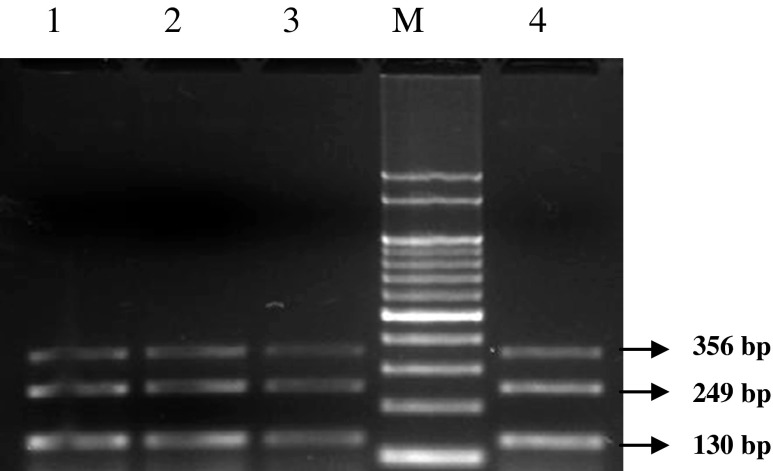

The serially diluted overnight grown culture of the Aeromonas spp. contained >250 cells/100 μl in 10-6 dilution; 75 and 96 cells/100 μl of A. hydrophila and A. sobria in 10-7 dilution; 7 and 9 cells/100 μl of A. hydrophila and A. sobria in 10-8 dilution. The multiplex PCR assay performed for testing the cell sensitivity with the DNA extracted from the serially diluted cells showed all the three genes got amplified within 4 h of enrichment in buffered peptone water, when the cell counts were >250; within 8 h when the counts were 75 cells and 96 cells of A. hydrophila and A. sobria, respectively; and within 12 h when contained 7 cells and 9 cells of the young culture of A. hydrophila and A. sobria, respectively (Fig. 3). The yields of the products were significantly high and distinguishable even when lower counts of cells were amplified by the multiplex PCR assay.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity of the MPCR assay for the detection of cells of A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp. after 12 h of enrichment. Lane 1- > 250 cells/ml in 10−6 dilution; Lane 2–75 cells/ml of A. hydrophila and 96 cells/ml of A. sobria in 10−7 dilution; Lane 3–7 cells/ml of A. hydrophila and 9 cells/ml of A. sobria in10−8 dilution; Lane 4-Positive control; Lane M- 100 bp DNA marker

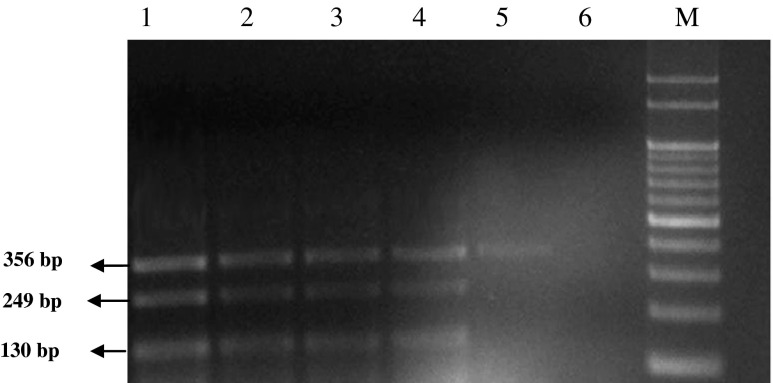

The genomic DNA sensitivity of the multiplex PCR assay performed with the serial dilution of genomic DNA of A. hydrophila and A. sobria showed amplification of genes even at 1 pg concentration of template DNA (Fig. 4). With regard to the sensitivity of the developed multiplex PCR assay, 7 and 9 cells of A. hydrophila and A. sobria could be detected in fish within 12 h of enrichment in buffered peptone water (Fig. 3) with the detection limit of 1 pg of DNA (Fig. 4). The sensitivity of the bacterial cells as well as genomic DNA reported for the MPCR or PCR assay vary widely. Pollard et al. (1990) reported a detection limit of 1 ng of the total DNA for the amplification of the aerolysin gene in A. hydrophila. On the other hand the MPCR assay developed by Balakrishna et al. (2010) could detect 50 CFU/g of A. hydrophila in fish samples based on aerolysin and hemolysin genes with overnight incubation in alkaline peptone water (APW-A) broth and the detection limit of the assay was 5 pg with pure genomic DNA. As the amplification of bacterial DNA directly from food complexes by PCR often give poor yield, enrichment of the samples prior to PCR has been recommended by many workers (Merino et al. 1995). Thus, the multiplex PCR assay developed had high sensitivity in terms of cells and genomic DNA content compared to that reported by other workers for Aeromonas spp.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of the MPCR assay for the detection of genomic DNA of A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp. Lane 1–1,000 pg; Lane 2–100 pg; Lane 3–10 pg; Lane 4–1 pg; Lane 5–100 fg; Lane 6–10 fg; Lane M, 100 bp DNA marker

The developed multiplex PCR assay performed for the representative colonies (162 Nos.) isolated from 73 commercial fresh fish samples comprising freshwater and marine fish and shellfish showed that 91 isolates were positive for Aeromonas spp. (Table 2). More specifically, of the 53 representative isolates from freshwater fishes, 33 were positive for Aeromonas spp., which consisted of 8 A. hydrophila, 6 A. sobria and 19 were other Aeromonas spp. The biochemical confirmation of the PCR positive isolates showed a different trend with 12 A. hydrophila, 6 A. sobria, 5 A. trota, 4 A. schubertii, 5 A. caviae, and 1 A. jandaei. There existed a difference in the number of positive isolates of A. hydrophila and A. sobria confirming by multiplex PCR and biochemical reactions. Multiplex PCR seemed to provide less positive results for A. hydrophila as four isolates biochemically confirmed as A. hydrophila were other Aeromonas spp. in the multiplex PCR assay.

Table 2.

Detection of Aeromonas spp. from different fish and fishery products by multiplex PCR assay and conventional methods

| Samples | No. of samples | No. of representative colonies tested | Number positive by MPCR with % in parenthesis | Number positive by biochemical tests with % in parenthesis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | ahh1 | asa1 | A. hydrophila | A. sobria | A. caviae | A. jandaei | A. trota | A. schubertii | |||

| Freshwater fishes | 23 | 53 | 33 (62) | 8 (24) | 6 (18) | 12 (36) | 6 (15) | 5 (18) | 1 (3) | 5 (15) | 4 (12) |

| Marine fishes | 20 | 46 | 26 (57) | 8 (31) | 8 (31) | 8 (31) | 8 (31) | 5 (19) | 3 (12) | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Fresh shrimps | 16 | 33 | 17 (52) | 6 (35) | 2 (12) | 6 (35) | 2 (12) | 0 | 2 (12) | 3 (18) | 4 (23) |

| Fresh squids | 14 | 30 | 15 (50) | 5 (33) | 6 (40) | 5 (33) | 6 (40) | 1 (7) | 0 | 3 (20) | 0 |

| Total | 73 | 162 | 91 (56) | 27 (16) | 22 (13) | 31 (19) | 22 (13) | 11 (7) | 6 (4) | 13 (8) | 8 (5) |

Value within the parenthesis denotes percentage

On the other hand, of the 46 representative colonies isolated from marine fishes, 26 were positive for Aeromonas spp., in which 8 were A. hydrophila, 8 A. sobria and 10 other Aeromonas spp. (Table 2). From the fresh shrimps, 17 were positive for Aeromonas spp. out of 33 representative colonies isolated. Among which, 6 were A. hydrophila, 2 A. sobria and 9 other Aeromonas spp. In the fresh squids, 15 out of 30 representative colonies were positive for Aeromonas spp. Of which 5 as A. hydrophila, 6 as A. sobria and 4 as other Aeromonas spp. were recorded. There was no misidentification of A. hydrophila or A. sobria in the above samples in the case of marine fishes, which is in little variance with the results obtained from freshwater fishes. The biochemical confirmation showed concurrence with the results of the developed multiplex PCR assay in the case of marine fishes. The other aeromonads identified by biochemical reaction belonged to different species such as A. caviae, A. trota, A. schubertii, A. veronii and A. jandaei. On an average, 91 representative isolates were positive for Aeromonas spp. corresponding to 55 Nos. of samples. The presence of A. hydrophila and A. sobria was 16 % and 13 % respectively, in the commercial fish samples examined. None of the samples contained both the A. hydrophila and A. sobria together.

The specificity of the PCR assay for the Aeromonas spp. has been checked by few authors. Pollard et al. (1990) faced some difficulties with the non-specific amplication of the aer gene specific for A. hydrophila with some Streptococcus spp. The developed MPCR assay was also checked for specificity with non-Aeromonas species mainly Salmonella typhi, S. paratyphi A, Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. alginolyticus and it did not detect them (Fig. 2). The multiplex PCR assays developed by Nam and Joh (2007) and Balakrishna et al. (2010) were specific for Aeromonas, as they did not amplify the selected virulent genes in E. coli, Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus vulgaris. Wang et al. (2003) reported cross reaction for the asa1 gene that was not detected in 5 of 21 A. sobria isolates. In this assay, such cross reactions were not noticed and no isolate other than A. hydrophila and A. sobria showed the presence of ahh1 and asa1 genes, respectively, rendering it to be specific.

Using the developed MPCR assay, it was confirmed that 56 % of the commercial fresh fish samples contained Aeromonas spp. based on the presence of 16S rRNA gene. Bin Kingombe et al. (2004) found 51 isolates as MPCR positive for Aeromonas spp. out of 65 isolates contributing to about 78 %, which is more or less similar to our present findings. The few contradictory results obtained by conventional biochemical tests and multiplex PCR assay in respect of A. hydrophila were analyzed in detail. There were reports that biochemical confirmation at times lacks specificity for some strains of bacterial pathogens (Park et al. 2003; Beaz-Hidalgo et al. 2010) and it need not be the same for all species. In this work, four isolates of A. hydrophila biochemically confirmed did not show the presence of hemolysin gene, ahh1 in the multiplex PCR assay. It has been earlier reported that the production of hemolytic cytotoxins has been regarded as strong evidence of pathogenic potential in Aeromonas spp. (Wang et al. 2003).

Conclusion

In conclusion the microbiological limit for Aeromonas spp. in foods including seafood in Commission Regulation EC No 1441/2007 is still lacking, but considering the worldwide increasing incidence of A. hydrophila and A. sobria infection in immuno-compromised individuals (Sanchez et al. 2005; Tsai et al. 2006) and its wide spread distribution in marine and freshwater environment, there is an immediate need to establish specific microbiological criteria in foods, especially seafood and an intensive monitoring on the occurrence of these species is strongly recommended to assess the human health risk arising from contaminated seafood consumption. As the conventional method for the isolation of Aeromonas spp. is a laborious process and further biochemical confirmation lacks specificity, multiplex PCR assay could be a powerful tool for the rapid and simultaneous detection of A. hydrophila, A. sobria and other Aeromonas spp. from the samples of fish and fishery products with more specificity and sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank the Dean, Fisheries College and Research Institute, Tuticorin for providing all facilities and support to carry out this study. This study was a part of M.F.Sc thesis submitted by the first author to the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India.

References

- Aggar WA, McCormick JD, Gurwith MJ. Clinical and microbiological features of Aeromonas hydrophila-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:909–913. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.6.909-913.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna K, Murali HS, Batra HV. Detection of toxigenic strains of Aeromonas species in food by a multiplex PCR assay. Indian J Microbiol. 2010;50:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s12088-010-0038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaz-Hidalgo R, Alperi A, Bujan N, Romalde JL, Figueras MJ. Comparison of phenotypical and genetic identification of Aeromonas strains isolated from diseased fish. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Kingombe CI, Huys G, Tonolla M, Albert MJ, Swings J, Peduzzi R, Jemmi T. PCR detection, characterization, and distribution of virulence genes in Aeromonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5293–5302. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5293-5302.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Kingombe CI, Huys G, Howald D, Luthia E, Swings J, Jemmia T. The usefulness of molecular techniques to assess the presence of Aeromonas spp. harboring virulence markers in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;94:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Kingombe CI, Aoust JYD, Huys G, Hofmann L, Rao M, Kwan J. Multiplex PCR method for detection of three Aeromonas enterotoxin genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:425–433. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01357-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovic R, Cobeljic M, Markovic M, Nikolic V, Ognjanovic M, Sarjanovic L, Makic D. Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome associated with Aeromonas hydrophila enterocolitis. Ped Nephrol. 1991;5:293–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00867480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell N, Acinas SG, Figueras MJ, Martinez-Murcia AJ. Identification of Aeromonas clinical isolates by restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1671–1674. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1671-1674.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan AM, Behram S, Joseph SW. Aerokey II: a flexible key for identifying clinical Aeromonas species. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2843–2849. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2843-2849.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra AK, Houston CW. Enterotoxins in Aeromonas-associated gastroenteritis. Microb Infect. 1999;1:1129–1137. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choresca CH, Gomez DK, Han JE, Shin SP, Kim JH, Jun JW, Park SC. Molecular detection of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from albino catfish, Clarias sp. reared in an indoor commercial aquarium. Korean J Vet Res. 2010;50:331–333. [Google Scholar]

- Devlieghere F, Lefevere I, Magnin A, Debevere J. Growth of Aeromonas hydrophila in modified-atmosphere packed cooked meat products. Food Microbiol. 2000;17:185–196. doi: 10.1006/fmic.1999.0305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes MC, Saavedra MJ, Martins C, Martinez-Murcia AJ. Phylogenetic identification of Aeromonas from pigs slaughtered for consumption in slaughterhouses at north of Portugal. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;146:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez CJ, Santos JA, Garcia-Lopez ML, Gonzalez N, Otero A. Mesophilic Aeromonas in wild and aquacultured freshwater fish. J Food Protect. 2001;64:687–691. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez MN, Santos JA, Otera A, Lopez GML. PCR detection of potentially pathogenic Aeromonas in raw and cold smoked freshwater fish. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93:675–680. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar S, Majumdar SD, Chakravorty S, Tyagi JS, Bhalla M, Sen MK. Detection of acid-fast bacilli in postlysis debris of clinical specimens improves the reliability of PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3580–3581. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3580-3581.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque QM, Sugiyama A, Iwade Y, Midorikawa Y, Yamauchi T. Diarrheal and environmental isolates of Aeromonas spp. produce a toxin similar to Shiga-like toxin 1. Current Microbiol. 1996;32:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s002849900043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuzenroeder MW, Wong CY, Flower RL. Distribution of two hemolytic toxin genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Aeromonas spp.: correlation with virulence in a suckling mouse model. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono I, Aoki T. Nucleotide sequence and expression of an extracellular hemolysin gene of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb Pathol. 1991;11:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90049-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard SP, Garland WJ, Gree MJ, Buckley JT. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for the hole-forming toxin aerolysin of Aeromonas hydrophila. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2869–2871. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2869-2871.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda JM, Kokka RP. The pathogenicity of Aeromonas strains relative to genospecies and phenospecies identification. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;15:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyasekaran G, Raj KT, Jeyashakila R, Thangarani AJ, Sukumar D. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction based assay for the detection of toxin producing Vibrio cholerae in fish and fishery products. Appl Microbiol Biotech. 2011;90:1111–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov SM. Aeromonas and Plesiomonas species. In: Doyle MP, Beuchat LR, Montville TJ, editors. Food microbiology, fundamentals and frontiers. 2. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2001. pp. 301–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Balakrishna K, Batra HV. Detection of Salmonella enteric serovar Typhi (S. typhi) by selective amplification of invA, viaB, fliC-d and prt genes by polymerase chain reaction in multiplex format. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;42:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino S, Rubires X, Knochel S, Thomas JM. Emerging pathogens: Aeromonas spp. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;28:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfort P, Baleux B. Dynamics of Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas sobria and Aeromonas caviae in a sewage treatment pond. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1999–2006. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.1999-2006.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacescu N, Israil A, Cedru C, Caplan D. Hemolytic properties of some Aeromonas strains. Roman Arch Microbiol Immunol. 1992;51:147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano H, Kameyama T, Venkateswaran K, Kawakami H, Hashimoto H. Distribution and characterization of hemolytic, and enteropathogenic motile Aeromonas in aquatic environment. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam IY, Joh K. Rapid detection of virulence factors of Aeromonas isolated from a trout farm by hexaplex PCR. J Microbiol. 2007;4:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pablos M, Rodriguez-Calleja JM, Santos JA, Otero A, Garcia-Lopez ML. Occurence of motile Aeromonas in municipal drinking water and distribution of genes encoding virulence factors. Inter J Food Microbiol. 2009;135:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TS, Oh SH, Lee EY, Lee TK, Park KH, Figueras MJ, Chang CL. Misidentification of Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria as Vibrio alginolyticus by the Vitek system. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;37:349–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin C, Benito Y, Garcia ML, Selgas D, Tormos J, Casas C. Influence of temperature, pH, sodium chloride, and sodium nitrite on the growth of clinical and food motile Aeromonas spp. strains. Arch Lebens Hyg. 1996;47:35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto AD, Terio V, Pinto PD, Tantillo G. Detection of potentially pathogenic Aeromonas isolates from ready-to-eat seafood products by PCR analysis. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2012;47:269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02835.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard DR, Johnson WM, Lior H, Tyler SD, Rozee KR. Detection of the aerolysin gene in Aeromonas hydrophila by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2477–2481. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2477-2481.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Colque-Navarro P, Kuhn I, Huys G, Swings J, Mollby R. Identification and characterization of pathogenic Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria associated with epizootic ulcerative syndrome in fish in Bangladesh. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:650–655. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.650-655.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj KT, Jeyasekaran G, Jeyashakila R, Thangarani AJ, Sukumar D. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Salmonella enteric serovars in shrimps in 4h. J Bacteriol Res. 2011;3:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Robson WL, Leung AK, Trevenen CL. Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome associated with Aeromonas hydrophila enterocolitis. Ped Nephrol. 1992;6:221–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00866324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez TH, Brooks JT, Sullivan PS, Juhasz M, Mintz E, Dworkin MS. Diarrhea in persons with HIV infection, United States, 1992–2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1621–1627. doi: 10.1086/498027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MS, Kuo CY, Wang MC, Wu HC, Chien CC, Liu JW. Clinical features and risk factors for mortality in Aeromonas bacteremic adults with hematologic malignancies. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivekanandhan G, Hathab AAM, Lakshmanaperumalsamy P. Prevalence of Aeromonas hydrophila in fish and prawns from the seafood market of Coimbatore, South India. Food Microbiol. 2005;22:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2004.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Clark CG, Liu C, Pucknell C, Munro CK, Kruk TMAC, Caldeira R, Woodward DL, Rodgers FG. Detection and characterization of the hemolysin genes in Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas sobria by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1048–1054. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1048-1054.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez MA, Catalan V, Apraiz D, Figueras MJ, Martinez-Murcia AJ. Phylogenetic analysis of members of the genus Aeromonas based on gryB gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:875–883. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogananth N, Bhakyaraj R, Chanthuru A, Anbalagan T, Nila KM. Detection of virulence gene in Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from fish samples using PCR technique. Global J Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;4:51–53. [Google Scholar]