Abstract

Introduction

“Fetus in fetu” (FIF) is defined as the abnormal monozygotic twin inside the body of its “host twin.” Intracranial FIFs are extremely rare.

Case presentation

A male premature newborn was admitted to the hospital due to a large intracranial tumor diagnosed in the 31st week of gestation. The child died before surgical treatment because of failure of the respiratory system due to fetal respiratory distress syndrome. During general autopsy, a large intracranial tumor with four relatively well-developed limbs was found. Microscopically, apart from relatively well-formed musculoskeletal structures of limbs that were covered with skin, there were haphazardly distributed different tissues or fragments of organs. However, various neuroectodermal derivatives were dominant.

Conclusion

We believe that intracranial FIFs, theoretically with poor prognosis, can be successfully curable in cases revealed prenatally, provided that optimal treatment is introduced and the achievement of proper pulmonary maturity of the host is accomplished prior to the operation of the tumor.

Keywords: Intracranial, Fetus in fetu, Teratoma, Tumor

Introduction

“Fetus in fetu” (FIF) was described by Meckel in about 1800 and is defined as the abnormal monozygotic twin (“parasitic twin”) inside the body of its “host twin” [1–7]. The overall incidence is 1 in 500,000 live births. In most cases, they are found in infants [3, 7]. Usually, FIF is anencephalic and acardiac with the most common location in the retroperitoneum (80 %), scull (8 %), and sacrococcygeal region (8 %) [2, 3, 8]. The nature of this peculiar and rare pathology is still disputable.

Case description

A male newborn (a son of a 19-year old primiparous healthy mother—delivery was by cesarean section in the 33rd week of gestation, family history of multiple births was not remarkable) was admitted to the Intensive Care Department of the University Children’s Hospital in Kraków in the first day of life due to a large intracranial tumor. The tumor was diagnosed in the 31st week of gestation during routine ultrasound examination and confirmed by MRI (Fig. 1a, b). The pregnancy was terminated in the 33rd week of gestation with prior induction of lung maturation by dexamethasone administered to mother.

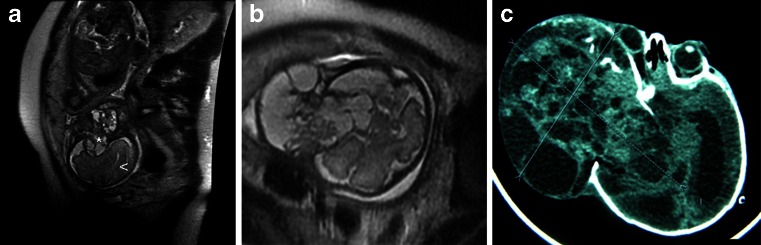

Fig 1.

a MRI SSFSET2, sagittal plane. A solid, cystic expansive process, arising from the temporal region and growing extra and intracranially in the head of the fetus, is seen (asterisk). The brain of the fetus is marked with an arrowhead. b MRI T2, an axial view of the head of the fetus. A marked discontinuity of the cranium and tumoral mass is visible. c CT of the head of newborn. A tumor is expanding within the structures of the craniofacial region of the head

The newborn was presented in a grave state with symptoms of respiratory failure. A large partially intracranial tumor with a diameter of 9 cm was found. The tumor distorted child’s head and was covered by grayish blue skin. The eyeball was dislocated with exophthalmos.

Low levels of serum proteins, hypoglycemia, dyselectrolytemia, and metabolic acidosis were found in laboratory tests. The level of AFP was 183,173.6 ng/ml. There was no cardiac defect or other abnormalities in the abdomen. CT confirmed that the tumor is expanding within the structures of the craniofacial region of his head (Fig. 1c).

It has been decided to remove the tumor surgically immediately, to give the child the chance of survival (Fig. 2a). However, just at the moment of introduction to anesthesia, the child abruptly deteriorated and the operation has not been started. Eventually, the child died the next day.

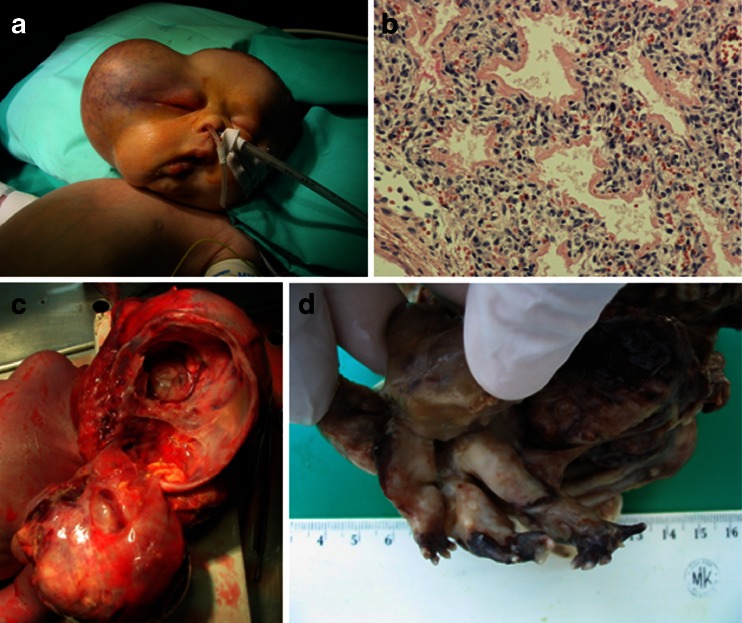

Fig. 2.

a The child prepared for the surgical removal of the tumor of the right aspect of the cranium, enormously disfiguring the child’s head. b The lung of the “host fetus” with the features of immaturity, atelectasis, and distinct hyaline membranes. Objective magnification ×20. c The autopsy of the child. The large tumor was removed from the cranium of the child but is still attached to the body of its host by a broad strand of fibrovascular “bridge.” The separation of the tumor from the cranial structures of the host child was very easy and it suggests that if not for the cardiorespiratory failure, the chances for a successful operation could have been large. d Especially striking finding was quite well-developed “extremities” of the parasitic fetus

The general autopsy showed that the male newborn has a weight of 3,100 g, with features of fetal respiratory distress syndrome (Fig. 2b). Apart from the head which measures 44 cm in diameter, no other abnormalities in the child’s body were found.

The large tumor of 9 cm in diameter occupied the right anterior, medial, and pterygopalatinal cranial fossae, partially displacing the child’s brain to the left. The tumor was entirely encapsulated and connected to the rest of the body by a distinct vascular stalk (Fig. 2c). It caused a significant destruction and an enormous defect of the cranial vault measuring 8 × 7.5 cm and 5.5 cm deep.

After the incision of the capsule, four relatively well-developed limbs (with fingers) appeared, protruding from the rest of the rather featureless tumor mass (Fig. 2d). Microscopically, apart from the relatively well-formed musculoskeletal structures of limbs (Fig. 3a) that were covered with skin (Fig. 3b), there were haphazardly distributed different tissues or fragments of organs like intestine (Fig. 3c), glands, muscles, and fat tissue. However, different neuroectodermal derivatives, like structures resembling primitive neural tubes, ganglions, neuroglial, and ependymal structures, were dominant (Fig. 3d).

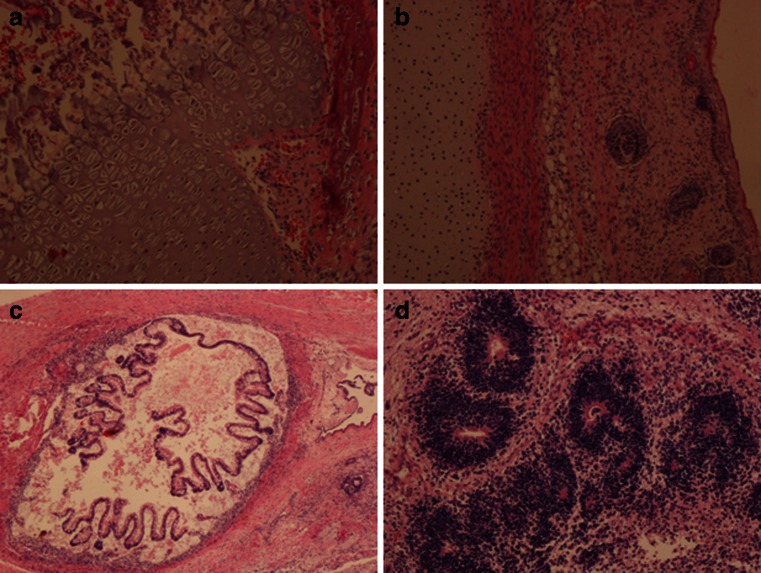

Fig. 3.

a The section shows an apparently normal region of bone growth plate of one of supposedly metacarpal bones of the parasitic fetus. A hyaline cartilage of the epiphyseal plate (growth plate) occupies the most of the picture. Formation of the trabecular bone of the diaphysis is in the upper left corner of the picture, and in the lower right corner, its epiphyseal side is shown with some osseous formation of the spongy bone of epiphysis. Objective magnification ×20. b A section through the superficial part of one of the extremities. From left to right: the cartilage, muscle, subcutaneous fat tissue, and skin with appendages. Objective magnification ×10. c A gut formation most probably corresponding to small intestine with villous-like undulations. It is noteworthy that there was achieved a rough “plan” of the gut’s tube. Objective magnification ×4. d Multiple neurotubular formations, which were numerous in the teratoma-like part of the parasitic fetus. Objective magnification ×10

There was no complete genetic profile obtained from histological materials, just individual genetic features in some STR structures. Examination of amelogenin gene in three specimens revealed chromosome X and Y characteristic for male sex.

Discussion

Pathogenesis of FIF is believed to be connected with unequal division of totipotential cells in blastocyst. In consequence, the monozygotic twin is incorporated into his partner through anastomosis of vitelline circulation [1, 4, 6, 9].

So far, about 100 cases of FIF have been reported and most of them are children. The abdominal region is the main location, but it can occur also in other anatomical sites: the mediastinum, pelvis, scrotum, sacrococcygeal region, neck, and skull [6, 7]. Parasitic fetuses are anencephalic, but limbs are described in 82.5 % and vertebral column in 91 % cases [2–4, 7, 10]. Mature teratoma is the main condition which should be taken into consideration during differential diagnostics [6–8, 10]. In spite of different pathogenesis, differentiation of FIF and teratoma is problematic. According to Willis and supported by many other investigators, the presence of the elements of the axial skeleton (vertebrae) is necessary to diagnose FIF [1, 3–8, 10]. FIF is a result of asymmetric division of a zygote in early stage of development. Thus, it is well differentiated and encapsulated by an amnion-like membrane, whereas teratoma is a result of the accumulation of pluripotent cells without features of organogenesis and vertebral segmentation or potential to develop mature tissue [4, 5, 7]. However, this postulate is questioned. Moreover, there were reported cases of FIF accompanied by teratoma [7]. This seems to be true also in the presented case. Such co-occurrence unnecessarily proves the common pathogenesis. One cannot exclude that, e.g., FIF may play a role of merely predisposing factor for the development of teratoma [7, 8, 11].

To date, there have been reported 15 cases of an intracranial fetus in fetu [12]. Usually, there were single cases, but numerous ones were also reported; for example, Saito and colleagues reported six intracranial FIFs [10]. Typically, first symptoms as hydrocephalus were noticed prenatally and were revealed during routine ultrasonography between 19 and 37 weeks of gestation [10, 12]. Prenatal diagnostics (MRI or USG) before birth suggested FIF or teratoma in two cases [7, 10]. Postnatally, enlargement of the head circumference in children was the main symptom [11, 13, 14]. In most cases, diagnosis was made during autopsy. The presence of vertebral column was not reported in all cases, but well development of limbs was common [1, 10–14]. If diagnosis had been made prenatally, different approaches could have been applied: the termination of the pregnancy, cephalocentesis, or observation and surgical treatment after birth on time by cesarean section [1, 7, 10]. In all these cases, the mass was totally removed. Radical resection performed in newborns and infants with intracranial tumors gave the best results. There were no recurrences, children’s development was normal, or they had only slight neurological defects [11, 12, 14].

In our case, the cause of death, aside from the large mass of the tumor, was the failure of the respiratory system due to fetal respiratory distress syndrome in the premature baby.

Conclusions

Intracranial FIF is a rare condition that should be suspected in all cases of hydrocephalus revealed prenatally. Highly differentiated teratoma should be taken into consideration during diagnostic procedures. Optimal treatment in case of prenatal diagnosis is termination of pregnancy on the condition that the fetus is able to survive independently and that should be followed by the total surgical removal of the mass.

Regardless of the pathogenetic and clinical considerations over this curious lesion, having in mind the particular localization of FIF in the presented case, it is hard to resist the general humanistic reflection, i.e., that the mythical tale of the birth of Athena might have been based upon a true event?

References

- 1.Goldstein I, Jakobi P, Groisman G, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Intracranial fetus-in-fetu. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1389–1390. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalifa NM, Maximous DW, Abd-Elsayed AA. Fetus in fetu: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arlikar JD, Mane SB, Dhende NP, Sanghavi Y, Valand AG, Butale PR. Fetus in fetu: two case reports and review of literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:289–292. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar AN, Chandak GR, Rajasekhar A, Reddy NCK, Singh L. Fetus-in-fetu: a case report with molecular analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:641–644. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodard TD, Yong S, Hotaling AJ. The ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure used for airway control in a newborn with cervical fetus in fetu: a rare case. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1989–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohan H, Chhabra S, Handa U. Fetus-in-fetu: a rare entity. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:195–197. doi: 10.1159/000098716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marnet D, Vinchon M, Kerdraon O, Joriot S, Chafiotte C, Dhellemmes P. Antenatal diagnosis of a third ventricular mass: fetus in fetu or teratoma? Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:887–891. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagausie P, Napoli Cocci S, Stempfle N, et al. Highly differentiated teratoma and fetus-in-fetu: a single pathology? J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:115–116. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin JH, Yoon CH, Cho KS, et al. Fetus-in-fetu in the scrotal sac of a newborn infant: imaging, surgical and pathological findings. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:945–947. doi: 10.1007/s003300050773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito K, Katsumata Y, Hirabuki T, Kato K, Yamanaka M. Fetus-in-fetu: parasite or neoplasm? A study of two cases. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:383–388. doi: 10.1159/000103301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JW, Park SH, Park SS, et al. Fetus-in-fetu in the cranium of a 4-month-old boy: histopathology and short tandem repeat polymorphism-based genotyping. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:410–414. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/5/410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huddle LN, Fuller C, Powell T, et al. Intraventricular twin fetuses in fetu. Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9:17–23. doi: 10.3171/2011.10.PEDS11196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuer GG, Schwartz ES, Storm PB. Cranial fetus in fetu. Case illustration. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:171. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afshfar F, King TT, Berry CL. Intraventricular fetus-in-fetu. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:845–849. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.6.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]