Abstract

Members of the Roseobacter clade are ecologically important and numerically abundant in coastal environments and can associate with marine invertebrates and nutrient-rich marine snow or organic particles, on which quorum sensing (QS) may play an important role. In this review, we summarize current research progress on roseobacterial acyl-homoserine lactone-based QS, particularly focusing on three relatively well-studied representatives, Phaeobacter inhibens DSM17395, the marine sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11 and the dinoflagellate symbiont Dinoroseobacter shibae. Bioinformatic survey of luxI homologues revealed that over 80% of available roseobacterial genomes encode at least one luxI homologue, reflecting the significance of QS controlled regulatory pathways in adapting to the relevant marine environments. We also discuss several areas that warrant further investigation, including studies on the ecological role of these diverse QS pathways in natural environments.

Keywords: Quorum sensing, signaling, symbiont, LuxI homologue, Ruegeria, Phaeobacter, Dinoroseobacter

1. Introduction

The Roseobacter clade is a diverse group of bacteria that belong to the Rhodobacteriaceae family of the Alphaproteobacteria, and its members, including 17 different genera, share greater than 89% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity [1,2]. Roseobacterial members have a diverse and broad ecological distribution but are exclusively restricted to marine or hypersaline environments [2,3]. Roseobacters have been characterized as ecological generalists and exhibit different lifestyle strategies, including heterotrophy, photoheterotrophy and autotrophy [3,4]. These bacteria are numerically abundant and are estimated to account for about 20%–30% of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes in ocean waters [2,5]. Furthermore, many members are found to be associated with marine invertebrates (such as marine sponges or corals), marine algae, dinoflagellates and sea grasses [6–9]. Several rosobacterial strains have been reported to cause diseases in marine invertebrates or algae [5]. An important ecological function of members in this clade is to participate in global sulfur cycling through metabolizing dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), an abundant organic sulfur compound produced by marine phytoplankton [10]. The pathways and enzymes participating in the demethylation or cleavage pathways have been comprehensively reviewed by Moran et al. [10].

It is now well accepted that most bacteria have chemical communication systems that allow signaling and response between individuals and thus can coordinate collective behaviors. Among these systems, quorum sensing (QS), a process by which bacteria sense and perceive their population density through the use of diffusible signals has been extensively studied in many bacterial species and the progress of the research on QS has been comprehensively reviewed [11–13]. A well-established form of QS among the Proteobacteria relies on acylated homoserine lactone (AHL) signal molecules.

2. General Mechanisms of AHL Quorum Sensing

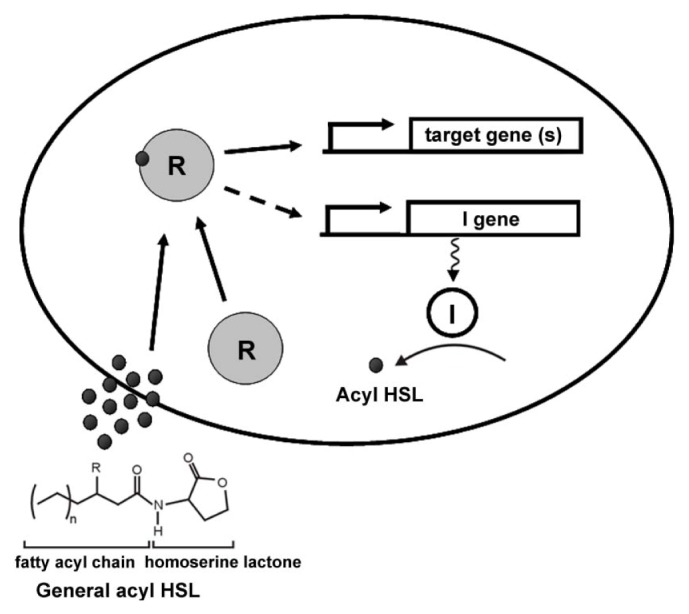

Signaling via AHLs involves enzymes that synthesize the molecular cues, AHL synthases, and response pathways including signal receptors that perceive these cues and directly or indirectly transduce the response to changes in bacterial behavior. The first of these systems to be identified was in the marine vibrios, and the production and response to AHLs was extensively studied in Vibrio fischeri, a bioluminescent symbiont of marine fishes and squids. Bioluminescence in V. fischeri is regulated by production of the 3-oxo-hexanoyl-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C6-HSL), so that only the dense populations associated with marine animals produce light. The enzyme that is responsible for AHL synthesis signals is called LuxI due to its role in bioluminescence control [14]. For sparse populations of V. fischeri, the concentration of the AHL is low and it can quickly transit across the bacterial cell membrane by passive diffusion to be diluted in the environment. As the population density increases, the AHL molecules accumulate proportionally. Once the population density and thus the concentration of the AHL reach a certain threshold concentration at which it binds to its cognate receptor, the AHL-responsive transcription factor called LuxR, a cytoplasmic protein. The complex of LuxR and AHL turns on or turns off a certain set of genes and thus coordinates the group behavior, including bioluminescence [13]. Many other bacteria are now known to utilize one or more LuxI–LuxR-type QS systems and AHL signal molecules. The range of QS-regulated phenotypes in these diverse quorum sensing bacteria extends well beyond bioluminescence and includes exoenzyme synthesis, antibiotic production, virulence factor elaboration, horizontal gene transfer, motility, and biofilm formation [11].

All AHL molecules have a homoserine lactone linked to a fatty acid chain via an amide bond. The chain length can vary from 4 to 18 carbons and the oxidation status of the third carbon can vary from fully reduced to fully oxidized (Figure 1). The substrates for LuxI-type enzymes are S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and fatty acyl precursors conjugated to the acyl carrier protein (ACP). The methionine in SAM provides the homoserine moiety, which is conjugated to the acyl chain donated by acyl-ACP [15,16]. Most LuxI-type enzymes are roughly 180–230 amino acids (aa) in length although in some cases can be longer (several such examples are found among the roseobacters) [4,17]. The LuxI-type protein can be divided into N-terminal and C-terminal regions. The N-terminal region, responsible for interactions with the substrate SAM, is the most conserved part of the enzyme and has eight invariable residues, Arg24, Phe29, Trp35, Asp46, Asp49, Arg70, Glu100 and Arg103 (the numbering is based on V. fischeri LuxI) [18]. In contrast, there is relatively low conservation in the C-terminal region, which is involved in the recognition of the more variable acyl chain, and the acyl-ACP fatty acid biosynthetic intermediate [18].

Figure 1.

Basic model of quorum sensing (QS) circuits. The eclipse represents a cell. The I gene represents the luxI homologue. R represents the acylated homoserine lactone (AHL) receptor LuxR protein. The dark unfilled circle represents the LuxI enzyme while the dark solid dots represent the AHL molecules. Stalked arrows indicate the transcription of the genes and the dotted line with arrow shows the positive feedback by the complex of the LuxR receptor and AHLs on the AHL synthase gene. The solid line with arrow depicts the function of R complex on the target genes. Squiggly line indicates translation of I gene and solid curved line with arrow indicates enzymatic function of I gene. The left corner shows the basic structure of a typical AHL molecule. N can vary from 4 to 18. R can be oxo, OH or H.

In many bacterial systems, the LuxI homologue is genetically linked with a cognate LuxR homologue, encoding the AHL receptor [19]. Most LuxR-type proteins are transcriptional activators that multimerize when associated with an AHL, and bind to sequences upstream of their target genes. The N-terminal domains of LuxR-type proteins contain the AHL-binding sites and the C-terminal domains encode the DNA binding motif. These two domains are linked together via a conformationally flexible linker. Binding to the cognate AHL stimulates the LuxR receptor to multimerize, and can also enhance the resistance to protease-mediated degradation of the LuxR-type protein [20–22]. The C-terminal domain of LuxR-type proteins contains a Helix–Turn–Helix motif (HTH) that is able to recognize a conserved palindromic DNA sequence element 18–22 bp in length and named the lux-type box upstream of target genes [23]. Often, luxI homologues have a lux-type box in their promoter region, thus their cognate LuxR protein can also stimulate the expression the AHL synthase, resulting in greater AHL synthesis and creating a positive feedback loop to amplify and perhaps insulate the QS response once engaged (Figure 1). In a small subset of LuxR-type proteins, the apoprotein that is not associated with AHL is the multimeric form and is proficient to bind DNA, and interaction with the ligand causes dissociation and inactivation [24].

LuxI and LuxR from V. fischeri represent one of the best characterized QS models, but this basic mechanism is now known to be widespread among diverse Proteobacteria, controlling a range of target functions including biofilm formation, motility, production of virulence factors, antibiotic synthesis and horizontal gene transfer. A large fraction of QS research has focused on animal and plant pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio harveyi, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Serratia spp. and Erwinia spp. Among marine bacteria the vast majority of studies have focused on Vibrio spp., with far less attention to other major marine bacterial groups.

Recently, however, there has been significant progress on the predominantly nonpathogenic Roseobacter clade, with insights into QS mechanisms that utilize AHLs as well as other signals. This review is aimed at summarizing the current understanding of QS pathways in this abundant and ecologically important marine bacterial clade and discussing future research. Much of our discussion focuses on recently characterized QS pathways in Phaeobacter inhibens DSM17395 (formerly known as P. gallaeciensis DSM17395) [34], the marine sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11 and the dinoflagellate symbiont Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL-12T (Table 1). In addition a comprehensive survey of the LuxI homologues in roseobacterial species from available genome sequences is included with roughly 80% of roseobacterial species encoding LuxI homologues, suggesting AHL mediated regulation plays important roles for this diverse and abundant bacterial clade in adapting to different niches in the marine environment.

Table 1.

Summary of the three roseobacterial species reviewed.

| Species | LuxI-LuxR | Isolation source | Signal profile | Function | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. inhibens DSM17395 | pgaRI | coastal water | 3-OH-C10-HSL | Temporal regulation of TDA production | [25–28] |

| Ruegeria sp. KLH11 | ssaRI, ssbRI sscI | marine sponge Mycale laxissima | 3-OH-C14-HSL, 3-OH-C14:1-HSL, 3-OH-C12-HSL | Activation of flagellar synthesis and swimming motility and inhibition of biofilm formation | [17,29,30] |

| D. shibae DFL12T | luxR1I1, luxR2I2, luxI3 | Dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima | 3-C18en-HSL | Cell morphology and flagellar biosynthesis | [31–33] |

3. AHL Production in the Roseobacters

Niches in the marine environments that contain high nutrient concentrations would be conducive to supporting dense bacterial populations that might reasonably be expected to utilize AHL-based QS. These environments include marine snow, invertebrates, macro- and microalgae, and plants. Gram et al. [35] screened bacteria isolated from marine snow for AHL production and showed that three roseobacterial isolates are able to produce AHL molecules detected by an A. tumefaciens AHL biological reporter system. Marine snow is made up of organic and inorganic particles and is rich in energy sources and nutrients. Bacteria can colonize marine snow and produce exoenzymes to degrade and catabolize the nutrient sources available in the aggregated organic particles [35].

Bruhn et al. [36] found that the strain Phaeobacter sp. 27-4 isolated from turbot rearing facility produced 3-hydroxyl-decanoyl-homoserine lactone (3-OH-C10-HSL). Taylor et al. [37] reported a bacterial strain in the genus Ruegeria isolated from the Australian marine sponge Cymbastela concentrica that produced AHLs detected by several AHL reporter systems sensitive to short acyl chain (C4–C6) length AHLs (based on Chromobacterium violaceum) and longer acyl chain (C6–C14) length AHLs (based on A. tumefaciens). In the same study, organic extracts from 27 of 37 different marine invertebrates including marine sponges, corals, ascidians and bryozoans stimulated the short-chain AHL reporter, indicating the presence of bacteria producing short-chain AHLs associated with these invertebrates. The specific AHLs responsible for induction of the reporter systems in these studies by Gram et al. [35] and Taylor et al. [37] were not chemically identified.

Wagner-Döbler et al. [1] screened 102 marine bacterial strains isolated from several different marine environments for AHL production using a mass spectrometric approach in parallel with biological reporters and found that 31 roseobacterial strains out of 67 alphaproteobacterial strains that were detected were able to significantly increase the fluorescence of their AHL reporter system, suggesting AHL production. The majority of these AHL-producing roseobacterial strains were isolated from either marine dinoflagellates or picoplankton. Subsequently, Mohamed et al. [6] reported that isolates from the Silicibacter-Ruegeria (SR) subgroup of the Roseobacter clade are the dominant AHL producers from bacterial isolates associated with two marine sponges, Mycale laxissima and Ircinia strobilina. These roseobacterial symbionts produce a mixture of short and long-chain length AHLs revealed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) coupled with a series of AHL biological reporters covering a range of AHL acyl chain length (C4–C16). Using similar methods, we have screened over 400 bacterial strains isolated from the same two sponges collected over three consecutive years and have found SR roseobacters to represent close to 75% of the AHL-producing isolates and the remaining AHL positive isolates were dominated by marine vibrios [38].

4. QS in Phaeobacter inhibens DSM17395

A P. inhibens strain DSM 17395 was isolated from the Atlantic coast near northwestern Spain [25]. The LuxI homologue pgaI in this strain synthesizes 3-hydroxydecanoyl-HSL (3-OH-C10-HSL) and the cognate LuxR homologue is called pgaR. There seems to be a minor effect of PgaR on the expression of pgaI [26]. Initially, it was found that null mutants of pgaI and pgaR cannot synthesize tropodithietic acid (TDA), an antibiotic produced by several members in the Roseobacter clade, and also fail to produce a yellow-brown pigment, when grown in marine broth with shaking for 24 h [26]. However, recent studies show that different carbon sources determine the role of QS in regulating the production of TDA [28] and the production is only delayed in QS mutants in agitated culture in marine broth [27]. More importantly, QS is not important for the TDA production when P. inhibens DSM17395 is used as a probiotic treatment in aquaculture system [27]. Interestingly, the antibiotic TDA itself may also be considered a signal molecule in P. inhibens DSM 17395. Addition of exogenous TDA into QS mutants increases pigment production and induces the expression of its own synthesis genes [26]. Support for the proposal that TDA is a QS molecule also comes from studies with Silicibacter sp. TM1040, a roseobacterial symbiont of dinoflagellates. Addition of TDA to Silicibacter sp. TM1040 culture also increases the expression of TDA synthesis genes most likely via TdaA [39]. This type of internal positive feedback indeed resembles that of many LuxI homologues in response to AHLs via their cognate LuxR proteins.

5. QS in the Marine Sponge Symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11

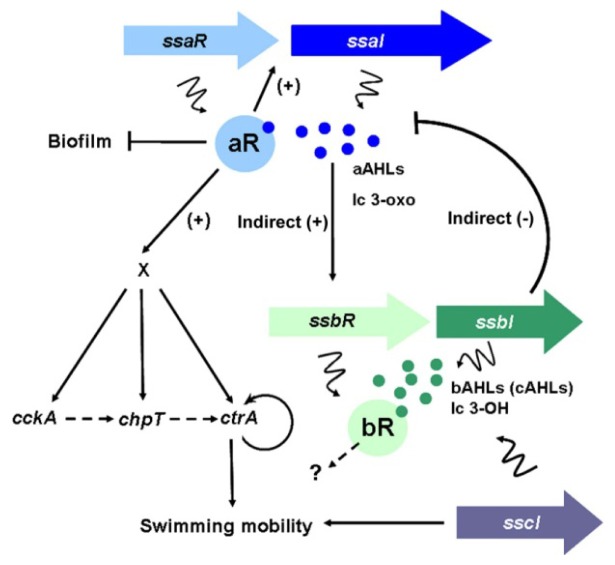

We have been examining Ruegeria sp. KLH11 (hereafter referred as KLH11) as a representative to study QS pathways in marine roseobacters. Arguably, KLH11 represents one of the best-studied roseobacterial species for its AHL-mediated QS circuits. Our studies have shown that KLH11 has very complex and interconnected QS networks (Figure 2). KLH11 has two LuxI–LuxR pathways and one LuxI solo, designated ssaIR, ssbIR and sscI, respectively. SsaIR are orthologous to SilI1R1 in Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 while SsbIR are orthologues of SilI2R2 [4,17].

Figure 2.

Interconnected QS network and model for ssaRI and cckA-chpT-ctrA regulatory circuit that controls KLH11 flagellar motility. Lengths of the ssaRI, ssbR, and sscI genes are drawn in scale. Genes and products are colored in corresponding colors, with R-genes more darkly colored and I-genes lighter colored. The dark blue dots represent the AHLs, mainly long chain (lc) 3-oxo-HSLs, synthesized by SsaI. The dark green dots represent the AHLs, mainly long chain (lc) 3-OH-HSLs, synthesized by SsbI. Lines with bars indicate inhibition and arrows indicate activation. Squiggly lines indicate translation of genes or products of enzyme action. The dashed line with arrows indicates the potential phosphate flow from CckA to CtrA via ChpT. The curved lines with arrows around CtrA indicate positive feedback loops. The “X” indicates the unknown regulator(s). The figure is modified from references [17] and [29].

SscI, which is absent in R. pomeroyi DSS-3, shares ca. 80% identity on the amino acid level to SsbI. Sequence conservation between the ssbI and sscI genes is strikingly confined to the coding sequences, without similarity in their flanking regions, suggesting that sscI is the result of a relatively recent gene duplication event from ssbI. Furthermore, the adjacent upstream regions that surround sscI are checkered with several transpose and phage integrase genes, suggesting a high local level of chromosomal rearrangement [40].

All three LuxI genes can synthesize AHLs when expressed both in Escherichia coli and KLH11. Each of the three LuxI-type enzymes drives synthesis of several different long chain AHLs when expressed in KLH11 and in the heterologous E. coli (both odd and even-numbered acyl side chain lengths can be detected). SsaI is biased towards synthesis of relative long chain 3-oxo-AHL derivatives (C12–C16) whereas SsbI and SscI tend to direct synthesis of long chain 3-hydroxylated AHLs (C12–C14), although these specificities are not absolute. Interestingly, wild type laboratory cultures of KLH11 mainly contain AHLs derived from SsbI or SscI, both of which synthesize an indistinguishable spectrum of AHLs [17,40]. However null KLH11 ssaI mutants do not produce detectable AHLs, suggesting that although SsaI-derived AHL levels are low in wild type cultures, their activity is required to produce SsbI and SscI-derived AHLs. SsaI-derived AHLs also seem to play a major role in regulating motility and biofilm formation [17,29]. Generally, long chain AHLs are more stable in alkaline environments (the average pH in ocean is ca. 8.2) compared to short chain AHLs [41,42]. Production of long chain length AHLs has also been reported in several other roseobacters [1]. Thus, it is possibly characteristic of roseobacters to produce long chain length AHLs, compounds with a relatively long half-life in the marine environment.

SsaR activates expression of ssaI in response to SsaI-directed AHLs, hence manifesting a positive feedback loop in the SsaRI system. A sequence upstream of ssaI gene is required for this activation; although it lacks homology to any known lux-type box, and is not an inverted repeat as are many LuxR-type proteins DNA binding sequences. In contrast SsbR does not activate the expression of ssbI. Similar to ssbI, the sscI solo gene with no genetically linked LuxR homologue is not regulated by either SsaR or SsbR [17,40].

Flagellar motility in KLH11 is strictly dependent on the SsaRI system [17,29]. SsaR and long chain AHLs are required, and indirectly activate the expression for cckA, chpT and ctrA genes, which in turn control flagellar motility gene expression. CckA is a hybrid two-component type sensor histidine kinase with its own internal receiver domain, including a phosphorylation site that contains a conserved aspartate [43]. ChpT is single domain histidine phosphotransferase (Hpt) protein, and CtrA is a response regulator with a conserved aspartyl receiver domain and a separate DNA binding domain. This pathway is well conserved throughout the Alphaproteobacteria and commonly controls motility, but outside of the Rhodobacteriaceae is frequently essential due to crucial roles in the regulation of cell division [44]. Among KLH11 and other roseobacters the CckA-ChpT-CckA pathway is non-essential, but controls flagellar motility. The intermediate regulator(s) that connects SsaRI and cckA-chpT-ctrA phosphorelay system remains to be identified [29]. The SsbRI system does not affect flagellar motility in KLH11 [17], whereas sscI does contribute, at a modest level [40].

Biofilm formation increases significantly in ssaI and ssaR mutants compared to wild type KLH11. Despite their lack of motility these mutants accumulate more rapidly on surfaces. Flagellar motility contributes to biofilm formation in many bacterial species. It is plausible that the effect of QS on biofilm formation in KLH11 is strictly due to the loss of flagellar motility. However, an ssaIfliC double mutant (fliC encodes the KLH11 flagellin) formed more robust biofilms compared the fliC mutant, suggesting that the KLH11 SsaRI system controls additional systems in addition to production of flagella that can affect biofilm formation [17].

Importantly and relevant to the environmental role for QS in roseobacters, active expression of ssaI and AHL molecules similar to those produced by SsaI are detected in whole extracts of wild-collected sponge tissue, which effectively connect findings on QS in the laboratory with the native host environment. Roseobacters are highly abundant in phytoplankton blooms or near macroalgae and are commonly found associated with marine invertebrates and organic particles. Motility is likely to play a critical role in many of these interactions. For example, mutants with motility defects in Silicibacter sp. TM1040 fail to attach to and form biofilms on host surfaces, specifically the dinoflagellate Pfiesteria piscicida [45], probably because TM1040 cannot chemotaxis to metabolites produced by the host, such as DMSP. In contrast, the KLH11 genome lacks any recognizable chemotaxis genes [30] and thus motility might play a different role in the symbiotic relationship with marine sponges. We hypothesize that the KLH11 QS pathway may play a role in dispersal. In nature, sponges actively pump large volumes (as many as 1000 L/h/kg of sponge tissue) of the surrounding seawater [7,8]. Given this tremendous flow rate microbial symbionts obtained from seawater at this stage likely do not require active motility to be introduced into the sponge host. Once KLH11-type bacteria colonize the sponge tissues and are provided a relatively nutrient rich environment, they may begin to grow to high density, perhaps beginning to aggregate. QS activation of motility and adherence inhibition may prevent aggregation in these crowded and potentially limiting microenvironments, and hence promote more uniform colonization of the host tissue or even stimulate release back into the water column. By coordinating motility and biofilm formation, motile KLH11 cells can mitigate against aggregation or even escape from their own aggregates. Experiments examining the colonization and distribution of KLH11 in live sponges, and tracking marked KLH11 QS mutants, may be the most direct approach to test these ecological hypotheses, and provide further insights into the environmental context of QS in this symbiotic system.

The proposed role in dispersal for KLH11 QS indeed resembles the role for QS in the water-borne pathogen V. cholerae. At low bacterial population densities such as when V. cholerae is in its aquatic reservoirs, it forms aggregates and biofilms. These aggregates and biofilms protect V. cholerae after ingestion into mammalian digestive tracts as they pass through the stomach into the intestine. The QS systems of V. cholerae (not AHLs but rather an alpha-hydroxy ketone and a furanosyl diester called autoinducer 2; both of which are chemically and mechanistically distinct from LuxR-LuxI systems) actively destabilize these biofilms in part through activation of motility and release motile, virulent cells into the intestinal environment where virulence factors such as cholera toxin can cause choleric dysentery. Explosive watery diarrhea releases large numbers of free-living V. cholerae into the aquatic environment where the cycle can re-initiate [46,47]. Furthermore, a similar dispersal model has also been proposed in Rhodobacter sphaeroides to prevent shading of photosynthetic activity, in which quorum sensing mutants form large aggregates [48].

6. QS in the Dinoflagellate Symbiont D. shibae

D. shibae was isolated from the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima [31] and lives symbiotically with its host marine alga. Genome sequence showed that it has three luxI homologues and both luxI1 and luxI2 are located on the chromosome and have a cognate luxR gene linked together while luxI3 is located on a plasmid without a cognate luxR gene [32]. Expression of each of these three luxI type genes in E. coli resulted in production of AHLs. LuxI1 synthesized the primary AHL molecule C18en-HSL whereas LuxI2 and LuxI3 both synthesized long chain HSLs different from that of LuxI1. Interestingly, deletion of luxI1 in D. shibae resulted in complete loss of AHL synthesis and transcriptomic analysis showed that luxI1 can activate the expression of luxI2 and luxI3. In KLH11, the overall production of AHL is depressed in an ssaI mutant but the transcription of ssbI or sscI is not significantly affected, indicating a different control mechanism over the overall AHL production [33]. Most interestingly, luxI1 controls the heterogeneity of cell morphology in D. shibae. Wild type cultures exhibited heterogeneous cell morphology with respect to cell shape and size while LuxI1 mutant cultures were homogenous in size and morphology. luxI1 indeed controls cell cycle related genes such as cckA, chpt and ctrA but it is unknown how these genes might control the cell size and morphology [33]. The phenotypic variation of cell size and morphology controlled by QS in D. shibae has been described as risk-spreading or bet-hedging [49], processes which can potentially maximize the fitness of the bacterial population in fluctuating environments. In KLH11, ssaIR system transcriptionally controls expression of the cckA-chpt-ctrA pathway to activate flagellar motility [29]. In D. shibae, luxI1 also activates expression of flagellar clusters and controls flagellar biosynthesis, and it seems likely that this is through cckA-chpt-ctrA similar to KLH11, but this has not been directly tested.

7. LuxI-LuxR Pathways in the Roseobacter Clade: A Bioinformatics Perspective

The first sequenced roseobacterial genome in the Roseobacter clade was Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 (previously described as Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3) in 2004 [4]. Thus far, 57 roseobacterial genomes have been sequenced; including both finished and draft genomes that are deposited in public databases (see http://img.jgi.doe.gov/). Probing these 57 sequenced roseobacterial genomes using the SsaI and SsbI sequences of Ruegeria sp. KLH11 [17] and also the RhIL-type luxI homologue of Roseobacter sp. MED193 (Locus tag: MED193_08053) reveals that 49 (ca. 87%) of these genomes encode LuxI homologues. These 49 roseobacters include members from almost all the known Roseobacter genera, except for Pelagibacter and Pseudovibrio, although only one or two strains are sequenced from either of these two genera (Table 1). Interestingly, Silicibacter sp. TM1040 does not encode any luxI homologue whereas all the other sequenced close relatives within the Silicibacter Ruegeria subclade encode luxI homologues. In total, 89 luxI homologues were retrieved from these genomes using an e value < 10−5 (signifying the likelihood of the alignments occurring by chance) as the cutoff (Table S1).

Proteins of the LuxI family are usually 200 aa in length and are best conserved in their amino terminal region (1–100 aa) and more degenerate in their C-termini. There are generally eight invariant N-terminal residues among these enzymes. This conservation reflects crucial interactions with the common substrate S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) for the homoserine moiety through N-terminal residues and interaction with the more variable acyl-acyl carrier protein (acyl-ACP) through the C-terminus [50,51]. Sequence alignment of all the Roseobacter LuxI type sequences showed that the N-termini are well conserved (data not shown), with six out of the eight conserved residues perfectly conserved. These trends are consistent with the larger LuxI family and suggest that these eight sites are also critical for the LuxI-type enzyme activity in Roseobacter clade. As expected, the C-terminal region is more variable [18]. Several LuxI homologues have an extra long C-terminus, such as SsaI in Ruegeria sp. KLH11 (284 aa) and SiI1 in R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (286 aa, the longest LuxI homologue identified to date). However the majority of LuxI-type proteins in this Roseobacter clade range from 190 to 250 aa in length (Table S1).

Roughly thirty roseobacters encode multiple luxI homologues in their genomes; Phaeobacter caeruleus 13, DSM 24564 has the largest number of luxI homologues with five (Table S1). Phylogenetic analysis of these LuxI sequences indicates that luxI homologues in the same strains probably result from a combination of gene duplication and horizontal gene transfer (data not shown). For example, SsaI (RKLH11_3375) is closely related to SilI1 in R. pomeroyi DSS-3 while it only shares about 35% identity to SsbI (RKLH11_260) at the amino acid level [17]. Instead, SsbI shares 81% identity to SscI. Notably, SsbI shares 93% identity to a LuxI homologue in Ruegeria sp. TW15 (Locus tag: 010100017784). One possible explanation is that sscI does not have a cognate luxR homologue and thus might be subject to a higher evolution rate. It is commonly observed among diverse bacteria that luxI homologues are genetically linked to their cognate luxR homologues. However, 17 luxI homologues among the roseobacters were not linked to a luxR homologue and thus these are described as luxI solos. Interestingly, all the 7 roseobacters, which encode 3 luxI homologues, have a luxI solo, whereas 8 out of 19 genomes that encode two luxI homologues have solos, and even 2 out of 26 genomes that encode a single luxI homologue unlinked to a luxR homologue (Table S1).

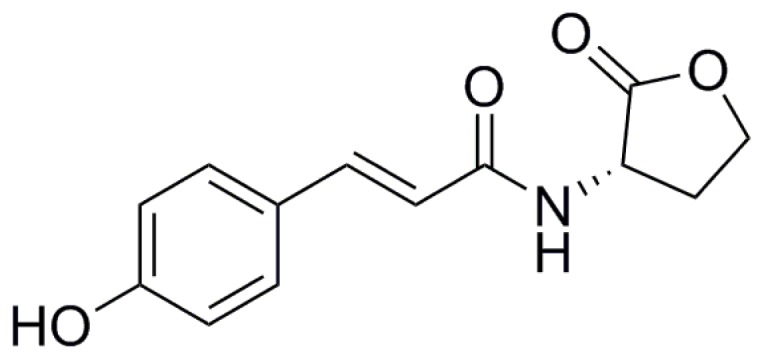

8. New Structural Variants of AHL

Recently, several novel types of signal molecules related to, but structurally distinct from AHLs have been reported [52–54]. The terrestrial and aquatic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris produces p-coumaroyl-HSL (pC-HSL), incorporating a coumaroyl aryl group rather than the acyl chain of AHLs (Figure 3) [52]. Remarkably, pC-HSL is only produced in the presence of p-coumarate, a compound synthesized by plants and certain algae and directly incorporated into the signal molecule via the LuxI-type protein RpaI. R. pomeroyi DSS-3, was also found to produce this type of molecule, but also required growth on p-coumarate [52]. Bioassays using a pC-HSL responsive reporter strain of R. palustris that cannot synthesize pC-HSL but that directs RpaR-dependent expression of a target rpaI-lacZ fusion revealed that KLH11 also produces similar molecules in the presence of coumarate. Surprisingly, this was independent of any of the three known LuxI-type enzymes suggesting the existence of novel Ruegeria enzyme(s) responsible for pC-HSL synthesis in the presence of coumarate [40]. Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 can also respond to the presence of p-coumarate produced by the microalga Emiliania huxleyi potentially via pC-HSL [55]. Furthermore Silicibacter sp. TM1040, which does not encode LuxI or LuxM homologues, produces the Roseobacter Motility Inducer (RMI) and this is stimulated by the presence of p-coumarate [56]. It is not known whether this is due to pC-HSL or some other compound. It is however clear that several roseobacters respond in complex ways to the presence of p-coumarate and this may drive intercellular signaling.

Figure 3.

Structure of p-coumaroyl-HSL based on reference Schaefer et al. [52].

9. QS Control of Virulence Factors and Secondary Metabolites

Several roseobacterial strains are associated with diseases in marine invertebrates and algae. For example, Roseovarius crassostreae can infect hatchery-raised Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) and cause seasonal mortalities in the northeastern United States [57,58]. Nautella sp. R11 (previously known as Ruegeria sp. R11) and Phaeobacter sp. LSS9 can cause a bleaching disease in the temperate-marine red macroalga, Delisea pulchra [59]. QS is well known to control the production of virulence factors in many different bacterial pathogens such as V. cholerae, V. harveyi, and P. aeruginosa [9]. An interesting link was proposed between QS and the production of virulence factors in the algal pathogens Nautella sp. R11 and Phaeobacter sp. LSS9. Both strains have two sets of LuxR-LuxI regulators and one additional luxR solo without a linked luxI homologue. Genomic comparisons between strains of Nautella and Phaeobacter which cause algal bleaching and related isolates that do not cause bleaching, reveals that the presence of specific luxR homologues correlates with the ability to cause bleaching [59]. However, additional experiments are required to establish a link between QS and virulence in these algal pathogens.

Roseobacters are also known to generate a variety of secondary metabolites [55,60,61]. QS might play a role in regulating the production of some of the metabolites, such as in P. inhibens DSM17395 as mentioned above [28]. Furthermore, Phaeobacter sp. Strain Y41 produces indigiodine via a nonribosomal peptide synthase and QS systems have been implicated in its control [61].

10. Future Directions

An increasing number of roseobacterial genome sequences are revealing the potential for extensive and diverse QS mechanisms. However, the regulatory networks that they orchestrate have only been studied in detail for a few specific species. Future research should focus on establishing more representative roseobacters, isolated from different ecological niches and representing a range of diversity, such as symbionts of algae and coral, for the study of their QS regulatory circuits, the AHLs and other signals they employ, and the output phenotypes that are controlled by QS. Better characterization of the LuxR-type protein target DNA binding sites, if they were well conserved, would help to identify genes that are controlled by QS using bioinformatics tools. As of yet, there is only one validated example of LuxR-type protein binding site that has been experimentally defined [17].

A major question remains regarding the ecological role of these diverse QS pathways in natural environments. A high level of detail has been revealed regarding the molecular mechanisms that control the symbiotic relationship between V. fischeri and its hosts, such as the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes. The extensive understanding of this system has relied on the fact that the host E. scolopes can be readily grown and reproduced under laboratory conditions and that powerful genetic techniques exit to manipulate V. fischeri. The squid light organ is a highly closed environment that establishes a monoculture of V. fischeri [62]. The roseobacterial symbionts that utilize quorum sensing face a much more open system, with a great diversity of microbial co-residents and much greater flux from the environment. It would therefore be extremely valuable to establish a parallel model to study the symbiosis between roseobacters and their hosts, which represents such an open system relative to the intimate V. fischeri-squid symbiosis. As discussed above, roseobacters also clearly represent a potentially important pool for discovering novel QS molecules. Thus for a diversity of reasons, further exploration of the QS process in roseobacters is worthwhile and well warranted.

11. Conclusions

Acyl-homoserine lactone-based QS is widespread in members of the Roseobacter clade, with over 80% of available roseobacterial genomes encoding at least one luxI homologue. The three systems discussed here, P. inhibens, the sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11, and the dinoflagellate symbiont D. shibae, provide some insights into the ecological roles of QS in this important clade of marine bacteria. Further examination of QS and the complex regulatory networks controlled by this signaling process in a greater diversity of roseobacters is needed to more fully elucidate the ecological roles of these diverse QS mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the National Science Foundation MCB #0703467 to Clay Fuqua et al., and #IOS-0919728 to Russell Hill. This is contribution number 13-117 from the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology and contribution no. 4850 from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Baltimore, MD, USA. A very recent publication [63] provides a useful review that is complementary to our review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wagner-Döbler I., Thiel V., Eberl L., Allgaier M., Bodor A., Meyer S., Ebner S., Hennig A., Pukall R., Schulz S. Discovery of complex mixtures of novel long-chain quorum sensing signals in free-living and host-associated marine alphaproteobacteria. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:2195–2206. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchan A., Gonzalez J.M., Moran M.A. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:5666–5677. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5665-5677.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran M.A., Belas R., Schell M.A., Gonzalez J.M., Sun F., Sun S., Binder B.J., Edmonds J., Ye W., Orcutt B., et al. Ecological genomics of marine. Roseobacters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:4559–4569. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02580-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran M.A., Buchan A., Gonzalez J.M., Heidelberg J.F., Whitman W.B., Kiene R.P., Henriksen J.R., King G.M., Belas R., Fuqua C., et al. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature. 2004;432:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner-Dobler I., Biebl H. Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;60:255–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamed N.M., Cicirelli E.M., Kan J., Chen F., Fuqua C., Hill R.T. Diversity and quorum-sensing signal production of Proteobacteria associated with marine sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slightom R.N., Buchan A. Surface colonization by marine Roseobacters: Integrating genotype and phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6027–6037. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01508-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor M.W., Radax R., Steger D., Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng W.L., Bassler B.L. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran M.A., Reisch C.R., Kiene R.P., Whitman W.B. Genomic insights into bacterial DMSP transformations. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012;4:523–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuqua C., Greenberg E.P. Listening in on bacteria: Acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackwell H.E., Fuqua C. Introduction to bacterial signals and chemical communication. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1–3. doi: 10.1021/cr100407j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller M.B., Bassler B.L. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuqua C., Parsek M.R., Greenberg E.P. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2001;35:439–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moré M.I., Finger L.D., Stryker J.L., Fuqua C., Eberhard A., Winans S.C. Enzymatic synthesis of a quorum-sensing autoinducer through use of defined substrates. Science. 1996;272:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer A.L., Hanzelka B.L., Eberhard A., Greenberg E.P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: Probing autoinducer—LuxR interactions with autoinducer analogs. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:2897–2901. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2897-2901.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zan J., Cicirelli E.M., Mohamed N.M., Sibhatu H., Kroll S., Choi O., Uhlson C.L., Wysoczynski C.L., Murphy R.C., Churchill M.E., et al. A complex LuxR-LuxI type quorum sensing network in a roseobacterial marine sponge symbiont activates flagellar motility and inhibits biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;85:916–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Churchill M.E., Chen L. Structural basis of acyl-homoserine lactone-dependent signaling. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:68–85. doi: 10.1021/cr1000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramoni S., Venturi V. LuxR-family “solos”: Bachelor sensors/regulators of signalling molecules. Microbiology. 2009;155:1377–1385. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.026849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J., Winans S.C. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1507–1512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S.H., Greenberg E.P. Genetic dissection of DNA binding and luminescence gene activation by the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:4064–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4064-4069.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiratisin P., Tucker K.D., Passador L. LasR, a transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes, functions as a multimer. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4912–4919. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.17.4912-4919.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens A.M., Greenberg E.P. Transcriptional activation by LuxR. In: Dunny G.M., Winans S.C., editors. Cell-Cell Signaling in Bacteria. ASM Press; Washington, DC, USA: 1999. p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai C.S., Winans S.C. LuxR-type quorum-sensing regulators that are detached from common scents. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;77:1072–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thole S., Kalhoefer D., Voget S., Berger M., Engelhardt T., Liesegang H., Wollherr A., Kjelleberg S., Daniel R., Simon M., et al. Phaeobacter gallaeciensis genomes from globally opposite locations reveal high similarity of adaptation to surface life. ISME J. 2012;6:2229–2244. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger M., Neumann A., Schulz S., Simon M., Brinkhoff T. Tropodithietic acid production in Phaeobacter gallaeciensis is regulated by N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:6576–6585. doi: 10.1128/JB.05818-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prol Garcia M.J., D’Alvise P.W., Gram L. Disruption of cell-to-cell signaling does not abolish the antagonism of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis toward the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum in algal systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:5414–5417. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01436-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger M., Brock N.L., Liesegang H., Dogs M., Preuth I., Simon M., Dickschat J.S., Brinkhoff T. Genetic analysis of the upper phenylacetate catabolic pathway in the production of tropodithietic acid by Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:3539–3551. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07657-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zan J., Heindl J.E., Liu Y., Fuqua C., Hill R.T. The CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay system is regulated by quorum sensing and controls flagellar motility in the marine sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zan J., Fricke W.F., Fuqua C., Ravel J., Hill R.T. Genome sequence of Ruegeria sp. strain KLH11, an N-acylhomoserine lactone-producing bacterium isolated from the marine sponge Mycale laxissima. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5011–5012. doi: 10.1128/JB.05556-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biebl H., Allgaier M., Tindall B.J., Koblizek M., Lunsdorf H., Pukall R., Wagner-Dobler I. Dinoroseobacter shibae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new aerobic phototrophic bacterium isolated from dinoflagellates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1089–1096. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner-Döbler I., Ballhausen B., Berger M., Brinkhoff T., Buchholz I., Bunk B., Cypionka H., Daniel R., Drepper T., Gerdts G., et al. The complete genome sequence of the algal symbiont Dinoroseobacter shibae: A hitchhiker’s guide to life in the sea. ISME J. 2010;4:61–77. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patzelt D., Wang H., Buchholz I., Rohde M., Grobe L., Pradella S., Neumann A., Schulz S., Heyber S., Munch K., et al. You are what you talk: Quorum sensing induces individual morphologies and cell division modes in Dinoroseobacter shibae. ISME J. 2013;7:2274–2286. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buddruhs N., Pradella S., Goker M., Pauker O., Pukall R., Sproer C., Schumann P., Petersen J., Brinkhoff T. Molecular and phenotypic analyses reveal the non-identity of the Phaeobacter gallaeciensis type strain deposits CIP 105210T and DSM 17395. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013;63:4340–4349. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.053900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gram L., Grossart H.P., Schlingloff A., Kiorboe T. Possible quorum sensing in marine snow bacteria: Production of acylated homoserine lactones by Roseobacter strains isolated from marine snow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:4111–4116. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4111-4116.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruhn J.B., Gram L., Belas R. Production of antibacterial compounds and biofilm formation by Roseobacter species are influenced by culture conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:442–450. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02238-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor M.W., Schupp P.J., Baillie H.J., Charlton T.S., de Nys R., Kjelleberg S., Steinberg P.D. Evidence for acyl homoserine lactone signal production in bacteria associated with marine sponges. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:4387–4389. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4387-4389.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zan J. Ph.D Dissertation. University of Maryland; College Park, MD, USA: May, 2013. Quorum sensing in bacteria associated with marine sponges Mycale laxissima and Ircinia strobilina. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geng H., Belas R. TdaA regulates tropodithietic acid synthesis by binding to the tdaC promoter region. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:4002–4005. doi: 10.1128/JB.00323-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zan J., Choi O., Meharena H., Uhlson C.L., Churchill M.E.A., Hill R.T., Fuqua C. A solo luxI-type gene directs acylhomoserine lactone synthesis and contributes to motility control in the marine sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11. Microbiology. 2013 doi: 10.1099/mic.0.083956-0. to be submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates E.A., Philipp B., Buckley C., Atkinson S., Chhabra S.R., Sockett R.E., Goldner M., Dessaux Y., Camara M., Smith H., et al. N-acylhomoserine lactones undergo lactonolysis in a pH-, temperature-, and acyl chain length-dependent manner during growth of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:5635–5646. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5635-5646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riebesell U., Zondervan I., Rost B., Tortell P.D., Zeebe R.E., Morel F.M. Reduced calcification of marine plankton in response to increased atmospheric CO2. Nature. 2000;407:364–367. doi: 10.1038/35030078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capra E.J., Laub M.T. Evolution of two-component signal transduction systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;66:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J., Heindl J.E., Fuqua C. Coordination of division and development influences complex multicellular behavior in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller T.R., Hnilicka K., Dziedzic A., Desplats P., Belas R. Chemotaxis of Silicibacter sp. strain TM1040 toward dinoflagellate products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:4692–4701. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4692-4701.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammer B.K., Bassler B.L. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu J., Mekalanos J.J. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puskas A., Greenberg E.P., Kaplan S., Schaefer A.L. A quorum-sensing system in the free-living photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:7530–7537. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7530-7537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veening J.W., Smits W.K., Kuipers O.P. Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:193–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gould T.A., Schweizer H.P., Churchill M.E. Structure of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa acyl-homoserinelactone synthase LasI. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1135–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson W.T., Minogue T.D., Val D.L., von Bodman S.B., Churchill M.E. Structural basis and specificity of acyl-homoserine lactone signal production in bacterial quorum sensing. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaefer A.L., Greenberg E.P., Oliver C.M., Oda Y., Huang J.J., Bittan-Banin G., Peres C.M., Schmidt S., Juhaszova K., Sufrin J.R., et al. A new class of homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals. Nature. 2008;454:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature07088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahlgren N.A., Harwood C.S., Schaefer A.L., Giraud E., Greenberg E.P. Aryl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in stem-nodulating photosynthetic bradyrhizobia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7183–7188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103821108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindemann A., Pessi G., Schaefer A.L., Mattmann M.E., Christensen Q.H., Kessler A., Hennecke H., Blackwell H.E., Greenberg E.P., Harwood C.S. Isovaleryl-homoserine lactone, an unusual branched-chain quorum-sensing signal from the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16765–16770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seyedsayamdost M.R., Case R.J., Kolter R., Clardy J. The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;4:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sule P., Belas R. A novel inducer of Roseobacter motility is also a disruptor of algal symbiosis. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:637–646. doi: 10.1128/JB.01777-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boettcher K.J., Barber B.J., Singer J.T. Use of antibacterial agents to elucidate the etiology of juvenile oyster disease (JOD) in Crassostrea virginica and numberical dominance of an alpha-proteobacterium in JOD-affected animals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:2534–2539. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2534-2539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boettcher K.J., Barber B.J., Singer J.T. Additional evidence that juvenile oyster diease is caused by a member of the Roseobacter group and colonization of nonaffected animals by Stappia stellulata-like strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:3924–3930. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.3924-3930.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandes N., Case R.J., Longford S.R., Seyedsayamdost M.R., Steinberg P.D., Kjelleberg S., Thomas T. Genomes and virulence factors of novel bacterial pathogens causing bleaching disease in the marine red alga Delisea pulchra. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martens T., Gram L., Grossart H.P., Kessler D., Muller R., Simon M., Wenzel S.C., Brinkoff T. Bacteria of the Roseobacter clade show potential for secondary metabolite production. Mol. Ecol. 2007;54:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cude W.N., Mooney J., Tavanaei A.A., Hadden M.K., Frank A.M., Gulvik C.A., May A.L., Buchan A. Production of the antimicrobial secondary metabolite indigoidine contributes to competitive surface colonization by the marine roseobacter Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:4771–4780. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00297-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruby E.G. Symbiotic conversations are revealed under genetic interrogation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:752–762. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cude W.N., Buchan A. Acyl-homoserine lactone-based quorum sensing in the Roseobacter clade: Complex cell-to-cell communication controls multiple physiologies. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:336. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.