Abstract

The Solanaceae family includes some important vegetable crops, and they often suffer from salinity stress. Some miRNAs have been identified to regulate gene expression in plant response to salt stress; however, little is known about the involvement of miRNAs in Solanaceae species. To identify salt-responsive miRNAs, high-throughput sequencing was used to sequence libraries constructed from roots of the salt tolerant species, Solanum linnaeanum, treated with and without NaCl. The sequencing identified 98 conserved miRNAs corresponding to 37 families, and some of these miRNAs and their expression were verified by quantitative real-time PCR. Under the salt stress, 11 of the miRNAs were down-regulated, and 3 of the miRNAs were up-regulated. Potential targets of the salt-responsive miRNAs were predicted to be involved in diverse cellular processes in plants. This investigation provides valuable information for functional characterization of miRNAs in S. linnaeanum, and would be useful for developing strategies for the genetic improvement of the Solanaceae crops.

Keywords: salt stress, miRNA, Solanum linnaeanum, high-throughput sequencing

1. Introduction

Salt stress is one of the most common abiotic stresses of crops. It was estimated that salt stress may affect half of all arable lands and will be a major factor of agriculture production for the coming decades [1]. Unlike other abiotic stresses, salt stress brings both osmotic stress and ion toxicity to crops. Under salt stress, crops can respond via cascades of molecular networks to change gene expression profile and posttranslational modifications involved in a broad spectrum of biochemical, cellular and physiological processes [2,3]. Therefore, an understanding of the basis of the salt stress response is important for strategies aimed at improving crop tolerance to salt stress.

miRNAs are endogenous non-coding small RNAs that are regulators of gene expression in organisms. They are known to play negative regulatory functions at the post-transcription level by inhibiting gene translation or cleaving target mRNAs via base-pairing their target mRNAs [4–6]. Many investigations indicated that plant miRNAs are involved in various important physiological processes, such as seed germination and root development [7–9]. In addition, increasing evidence has shown that miRNAs play important roles in the response of plants to biotic and abiotic stresses [10]; the expression levels of miRNAs were changed in plants infected with virus and fungus [11–13], and miRNAs were identified to be involved in plant response to abiotic stresses such as temperature [14,15], drought [16,17], metals [18,19], and salt [20–22].

The Solanaceae family includes some agriculturally important crops such as potato (Solanum tuberosum), eggplant (S. melongena), tomato (S. lycopersicum), and pepper (Capsicum annuum), and they often suffer from salt stress that can cause reduction of production, especially in greenhouse production. S. linnaeanum, which was used to construct a comparative genetic linkage map of eggplant, has tolerance to salt stress [23,24], however, little is known about the mechanism in response to salt stress. Comparative genomic studies revealed that relatively few genome rearrangements and duplications occurred in the evolutionary history of the Solanaceae species [25–28]. Although little information is known about the genomes of S. linnaeanum and S. melongena, the published data of other plants, especially those from Solanaceae family, may provide sufficient reference.

In the present study, using high-throughput sequencing, a large number of miRNAs and their response to salt stress in S. linnaeanum roots are identified and characterized. The results lay the foundation for further investigation and better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms for the plant response to salt stress. In addition, it also provides important information for genetic improvement of Solanaceae crops to salt stress.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Deep Sequencing Results of Small RNAs from S. linnaeanum Roots

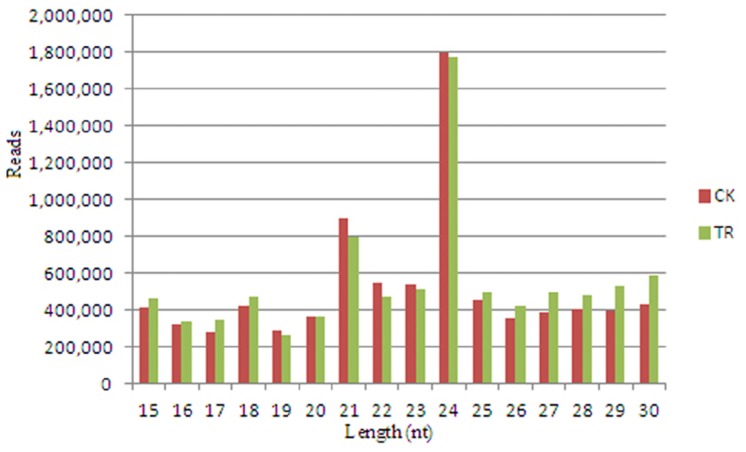

To identify the miRNAs and their response to salt in S. linnaeanum, two small RNA libraries were generated from roots of NaCl-free (CK) and NaCl-treated (TR). Deep sequencing generates 21,284,496 and 13,989,100 raw reads in two libraries. After removal of low-quality and corrupted adapter sequences, 8,462,890 and 8,999,145 mappable reads remain in two libraries. The size distribution of mappable reads is assessed (Figure 1, Table S1). The data show that 24 nt small RNA is the major size class, followed by 21, 23, 30 and 22 nt small RNA. Similar results were reported in some other plant species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana [29,30], Medicago truncatula [31], Oryza sativa [32], Arachis hypogaea [33], Cucumis Sativus [34], Nicotiana tabacum [35], and Citrus trifoliate [36].

Figure 1.

Length distribution of mappable small RNAs in two databases of S. linnaeanum roots. TR represents library of NaCl treatment, and CK represents library of control. The number in vertical axis is the total reads of all small RNAs in a certain length.

Because details of S. linnaeanum genome are limited, these mappable reads are analyzed with genome information of tomato and other plants. The results show that 5.51% reads of CK and 4.86% reads of TR are mapped to known plant pre-miRNAs in miRbase. Reads from CK (24.17%) and TR (24.29%) are mapped to plant repeats, mRNA, and other RNAs including tRNA, rRNA, snRNA and snoRNA. In addition, some reads that cannot be mapped to pre-miRNAs in miRbase and other RNAs are mapped to tomato genome sequences, and a fraction of them potentially form hairpins. Also, nearly half of these reads have no mapping information (Table 1). To eliminate possible sequencing errors, only those sequences with more than five reads in either of the two libraries are further analyzed.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of sequencing reads in the two libraries.

| Category | CK | Percent (%) | TR | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw reads | 13,989,100 | 21,284,496 | ||

| Mappable reads | 8,462,890 | 100.00 | 8,999,145 | 100.00 |

| Mapped to miRNA | 466,136 | 5.51 | 437,144 | 4.86 |

| Mapped to mRNA | 723,297 | 8.55 | 793,475 | 8.82 |

| Mapped to RFam | 1,315,886 | 15.55 | 1,387,942 | 15.42 |

| Mapped to Repbase | 5,674 | 0.07 | 4,745 | 0.05 |

| Mapped to genome | 1,763,934 | 20.84 | 2,063,801 | 22.93 |

| No hit | 4,187,963 | 49.49 | 4,312,038 | 47.92 |

2.2. Conserved miRNAs in S. linnaeanum Roots

To identity the conserved miRNAs in S. linnaeanum roots, small RNA sequences are mapped to tomato and other plant miRNAs in miRBase. Based on sequence homology (number of mismatch < 3), 98 known miRNAs and 7 miRNAs* are found (Table S2). The majority of these miRNAs are 20–22 nt long, and 56 of them are 21 nt long. These identified conserved miRNAs correspond to 37 families. The number of miRNA members in each known family shows significant divergence. The miR166 family is the largest one with 11 members, and for the family of miR171, miR396, and miR156, each of them has 7, 6, and 5 members respectively. Six families including miR159, miR162, miR167, miR168, miR319, and miR390 contain four members, and the remaining 27 miRNA families contain one to three members.

The read counts of miRNAs in sequencing libraries can be used as an index to estimate their relative abundance. In this study, the read counts differ among the miRNAs, which indicate that their expressions varied. Counting redundant miRNA reads reveals that 18 out of 98 known miRNAs and 2 miRNAs* are represented by more than 1000 reads in both libraries, and 5 of them, sli-miR166e (201,378 reads), sli-miR2911c (48,948 reads), sli-miR396d (29,823 reads), sli-miR166f (29,594 reads), and sli-miR403a (28,676 reads) are the most frequent. In addition, sequence analysis shows that the relative abundance of certain member within the miRNA families varies greatly, suggesting functional divergence within the family. For instance, reads of the sli-miR166 family vary from 10 reads (sli-miR166k) to 201,378 reads (sli-miR166e). Similar results are observed in some other miRNA families, such as sli-miR396 (7-29,823 reads) and sli-miR2911 (256-48,948 reads). The above results indicate the different expression levels of different miRNAs in roots, and may be the result of tissue specific or developmental expression.

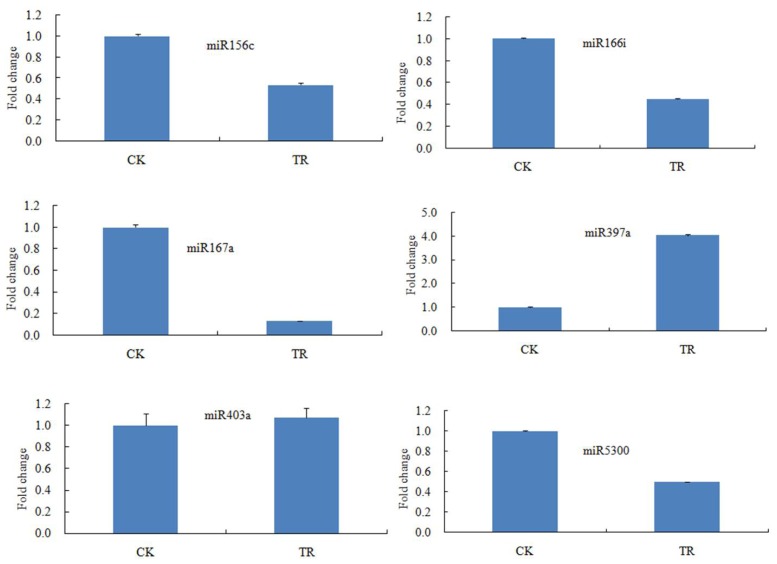

2.3. Validation of miRNAs in S. linnaeanum Roots

To verify the results of RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis, six miRNAs (sli-miR156c, sli-miR166i, sli-miR167a, sli-miR397a, sli-miR403a and sli-miR5300) are selected randomly for validation by qRT-PCR. According to the Illumina sequencing results, these miRNAs are four down-regulated miRNAs, one up-regulated miRNA and one no responsive miRNA. As shown in the Figure 2 and Table S3, the expression changes detected by qRT-PCR for 4 miRNAs (sli-miR156c, sli-miR166i, sli-miR397a and sli-miR403a) are similar to the results of Illumina sequencing. For sli-miR167a and sli-miR5300, the results have small differences, but they all show down regulation. This may be induced by sequencing error or sampling difference. Above results suggest that miRNAs and their expression changes under NaCl stress have been successfully discovered from S. linnaeanum roots by Illumina sequencing.

Figure 2.

Validation of selected miRNAs in roots by qRT-PCR. The data are the average of three qRT-PCR replicates for each sample from three biological repeats. Small nuclear RNA U6 is used as an internal reference. Error bars indicate one standard deviation of three different biological replicates. The expression changes of six miRNAs detected by qRT-PCR are consistent with the Illumina sequencing results.

2.4. NaCl-Responsive miRNAs in S. linnaeanum Roots

A deep sequencing approach can be used as a powerful tool for profiling miRNA expression [15,31]. The changes in the frequency of miRNAs between the NaCl-treated and control libraries might indicate that their expression is regulated in response to NaCl stress. To minimize noise and improve accuracy, only the 18–24 nt miRNAs with normalized sequence reads over 10 in at least one library are selected for comparison. miRNAs with log2(TR/CK) > 1 and p < 0.05 are designated as up-regulated. Similarly, miRNAs with log2(TR/CK) < −1 and p < 0.05 are designated as down-regulated. As showed in Table 2, under the stress of NaCl treatment, 11 miRNAs belonging to eight families are down-regulated, and three miRNAs belonging to three families are up-regulated. The above results indicate that the number of NaCl-induced down-regulated miRNAs is more than that of up-regulated miRNAs.

Table 2.

NaCl-responsive miRNAs and their targets. The value of TR/CK is the ratio between normalized count from library TR and CK.

| miRNA | Log2(TR/CK) | p value | Predicted target | Putative function of target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sli-miR156b | −1.01 | 2.46 × 10−127 | SGN-U325281 | Squamosa promoter-binding protein |

| sli-miR156c | −1.18 | 2.72 × 10−52 | SGN-U317176 | Squamosa promoter-binding protein |

| sli-miR162b | −1.25 | 8.35 × 10−99 | Solyc10g005130.2.1 | Ribonuclease 3-like protein 3 |

| sli-miR164c | 1.03 | 3.57 × 10−16 | SGN-U327571 | Lipase-related |

| sli-miR166d | 1.97 | 1.02 × 10−45 | Solyc11g011150.1.1 | DNA repair protein Rad4 family |

| sli-miR167a | −1.45 | 4.26 × 10−166 | SGN-U313907 | Annexin 1 |

| sli-miR167b | −1.25 | 5.57 × 10−15 | Solyc03g095940.1.1 | LOB domain family protein |

| sli-miR171b | −1.18 | 1.89 × 10−47 | SGN-U333058 | Scarecrow transcription factor family protein |

| sli-miR171e | −1.08 | 1.24 × 10−12 | SGN-U333058 | Scarecrow transcription factor family protein |

| sli-miR172a | −1.66 | 1.94 × 10−44 | SGN-U563871 | Floral homeotic protein APETALA2 |

| sli-miR319a | −1.07 | 2.28 × 10−28 | SGN-U31990 | TCP family transcription factor |

| sli-miR397a | 1.91 | 1.04 × 10−43 | SGN-U327694 | Laccase |

| sli-miR399b | −1.14 | 9.82 × 10−14 | Solyc03g031410.1.1 | Unknown Protein |

| sli-miR5300 | −1.92 | 1.55 × 10−155 | SGN-U336733 | CC-NBS-LRR protein |

To understand the potential functions of NaCl-responsive miRNAs, 31 target genes (Table S4) for these miRNAs are predicted, and the representative results are listed in Table 2. These genes were reported to be involved in many plant physiological processes, such as plant development, metabolism, and defense. Interestingly, different members in a miRNA family may target the same or different genes. For example, both sli-miRNA156b and sli-miRNA156c can target genes encoding squamosa promoter-binding protein-like, which indicates that they are functionally conservative. The same results are observed for sli-miR171b and sli-miR171e, and they all target the gene encoding scarecrow transcription factor family protein. However, for sli-miR167a and sli-miR167b, which can target different genes, their functions may be differentiated by sequence variation.

As S. linnaeanum is salt-tolerant, these salt responsive miRNAs may play an important role for salt tolerance. Some miRNAs, such as Zea mays miR166, miR159, miR156 and miR319, and Arabidopsis miR393, miR397b, and miR402, have been reported to show altered expression profile under salt stress [21,37]. In the present study, one of the up-regulated miRNA, sli-miR397a, is predicted to target a laccase gene, which was reported to reduce root growth under dehydration [38]. Similarly, another up-regulated miRNA, sli-miR166d, is predicted to target a DNA repair protein RAD4 family gene which was previously found as a key repair factor that directly recognizes DNA damage and initiates DNA repair, and recently it was found to regulate protein turnover at a postubiquitylation step [39]. Because of the salt tolerance of S. linnaeanum, it is possible that the roots do not suffer with serious injuries such as reduced growth and DNA damage. Therefore, the two potential targets do not need to show high expression to alleviate the injuries. However, further investigations are needed to confirm the above hypothesis.

Unlike the targets of up-regulated miRNAs in S. linnaeanum, some of the down-regulated miRNAs target mRNAs of transcription factors, indicating an upstream regulation of miRNAs during the response to salt stress. sli-miR171b and sli-miR171e are predicted to target a scarecrow transcription factor gene which was reported to be involved in ground tissue formation in Arabidopsis root [40]. sli-miR172a is predicted to target an Floral homeotic protein APETALA2 gene. SlAP2a, the true ortholog of AP2 in tomato has been found to control fruit ripening via regulation of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling [41]. However, the role of AP2 in response to salt stress has not been described in detail. sli-miR319a is predicted to target a TCP family transcription factor gene which was reported to play a pivotal role in the control of morphogenesis of shoot organs by negatively regulating the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis [42]. The above results indicate that the function involved in the response to salt stress of these potential targets needs to be explored in depth. The identification of salt-responsive miRNAs that target these genes may suggest additional roles for the defense against salt stress.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Materials and NaCl Treatment

A wild eggplant species, S. linnaeanum (PI388846) is used in this study. The seeds are surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol, and allowed to germinatein 30 °C. The uniform germinated seeds are sown in pots containing commercial nursery substrate. The seedlings are grown in an incubator with a 16 h photoperiod at a temperature regime of 25 °C. When the seedlings develop five true leaves, uniform seedlings are picked out and irrigated with 150 mM NaCl for salt treatment or the distilled water as a control. The roots of the NaCl treated and control plants are harvested after 24 h. The collected roots are pooled with ten plants and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

3.2. Small RNA Library Construction and Sequencing

Total RNA is extracted with the Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, Canada and treated with DNase I according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The small RNA libraries are constructed using the Truseq™ Small RNA Preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The purified cDNA library from 15 to 32 nt small RNAs is used for cluster generation on Illumina’s Cluster Station and then sequenced on Illumina GAIIx (San Diego, CA, USA). Raw sequencing reads are obtained using Illumina’s Sequencing Control Studio software version 2.8 (SCS v2.8, San Diego, CA, USA) following real-time sequencing image analysis and base-calling by Illumina’s Real-Time Analysis version 1.8.70 (RTA v1.8.70).2.1.1 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

3.3. Analysis of Small RNA Sequencing Data

A proprietary pipeline script, ACGT101-miR v4.2 (LC Sciences, Houston, TX, USA), is used for sequencing data analysis. The “impurity” reads due to sample preparation, sequencing chemistry and processes, and the optical digital resolution of the sequencer detector are removed. Those remaining sequences are grouped by families (unique sequences). Thereafter, families that match known plant repeats, mRNA, rRNAs, tRNAs, snRNAs, and snoRNAs were removed. The remaining unique sequences are mapped to known plant miRNAs from miRBase and Pre-miRBase (Version 17.0, ftp://mirbase.org/pub/mirbase/CURRENT, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and S. lycopersicum genome database (PlantGDB, ftp://ftp.plantgdb.org/download/Genomes/SlGDB/ITAG2_genomic.fasta).

The number of read copies from each sample is tracked during mapping and normalized for comparison. The normalization of sequence counts in each sample is achieved by dividing the counts by a library size parameter of the corresponding sample. The library size parameter is a median value of the ratio between the counts a specific sample and a pseudo-reference sample. A count number in the pseudo-reference sample is the count geometric mean across two samples. For miRNA expression analysis, p value calculation is performed with the method introduced by Audic and Claverie [43].

3.4. miRNA Validation by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

The identified S. linnaeanum miRNAs are validated by using quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR). In this study, six conserved miRNAs (sli-miR156c, sli-miR166i, sli-miR167a, sli-miR397a, sli-miR403a and sli-miR5300) are validated. Total RNA is isolated from roots of CK and TR, which are samples of parallel experiments for RNA sequencing. For determination of miRNA expression, RNAs are reverse-transcribed by miScript II Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), which adds a poly (A) tail to the 3′-end of miRNA and with transcription led by a known oligo-dT ligate. SuperReal PreMix (SYBR Green, TIANGEN, Beijing, China) is used for qRT-PCR. Small nuclear RNA U6 is used as an internal reference. The primers for the 6 miRNAs are universal primers (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) and corresponding miRNA sequences. qRT-PCR experiments are performed on Roche LightCycler 480 II. PCR program is set as: (1) 95 °C, 15 min; (2) 95 °C, 10 s, thereafter 60 °C, 30 s, 40 cycles. All reactions are run in three replicates for each sample from three biological repeats.

3.5. Prediction of miRNA Target Genes

The putative target sites of miRNA are identified using the psRNATarget program (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) with default parameters [44]. Because there is not enough genome information for S. melongena and S. linnaeanum, the database of tomato S. lycopersicum is used as the sequence library for target search.

4. Conclusions

In this study, by using high-throughput sequencing and taking advantage of the genome information of other plants, 98 known miRNAs were discovered in S. linnaeanum roots, and 14 of them show response to salt stress. The potential targets of the identified salt responsive miRNAs are also predicted based on sequence homology search. However, the further investigation for the function of potential target genes still needs to be performed. As more salt tolerance related miRNAs are confirmed, artificial miRNA will be a powerful tool to create elite plant germplasm with salt tolerance.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (31101542); Natural Science Foundation (BK2011675); and Independent Innovation Foundation of Agricultural Sciences (CX (13)2003) of Jiangsu Province, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang W., Vinocur B., Altman A. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: Towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta. 2003;218:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borsani O., Zhu J., Verslues P.E., Sunkar R., Zhu J.K. Endogenous siRNAs derived from a pair of natural cis-antisense transcripts regulate salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;123:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinocur B., Altman A. Recent advances in engineering plant tolerance to abiotic stress: Achievements and limitations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005;16:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones-Rhoades M.W., Bartel D.P., Bartel B. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voinnet O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:669–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P.P., Montgomery T.A., Fahlgren N., Kasschau K.D., Nonogaki H., Carrington J.C. Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant J. 2007;52:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyes J.L., Chua N.H. ABA induction of miR159 controls transcript levels of two MYB factors during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2007;49:592–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez L., Bussell J.D., Pacurar D.I., Schwambach J., Pacurar M., Bellini C. Phenotypic plasticity of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis is controlled by complex regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR transcripts and microRNA abundance. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3119–3132. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunkar R., Chinnusamy V., Zhu J., Zhu J.K. Small RNAs as big players in plant abiotic stress responses and nutrient deprivation. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazzini A.A., Hopp H.E., Beachy R.N., Asurmendi S. Infection and coaccumulation of tobacco mosaic virus proteins alter microRNA levels, correlating with symptom and plant development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12157–12162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705114104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu S., Sun Y.H., Amerson H., Chiang V.L. MicroRNAs in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) and their association with fusiform rust gall development. Plant J. 2007;51:1077–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L., Jue D., Li W., Zhang R., Chen M., Yang Q. Identification of MiRNA from eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) by small RNA deep sequencing and their response to Verticillium dahliae infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Z., Zhang L., Xu C., Yuan S., Zhang F., Zheng Y., Zhao C. Uncovering small RNA-mediated responses to cold stress in a wheat thermosensitive genic male-sterile line by deep sequencing. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:721–738. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.196048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X., Wang H., Lu Y., de Ruiter M., Cariaso M., Prins M., van Tunen A., He Y. Identification of conserved and novel microRNAs that are responsive to heat stress in Brassica rapa. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1025–1038. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrera-Figueroa B.E., Gao L., Diop N.N., Wu Z., Ehlers J.D., Roberts P.A., Close T.J., Zhu J.K., Liu R. Identification and comparative analysis of drought-associated microRNAs in two cowpea genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B., Qin Y., Duan H., Yin W., Xia X. Genome-wide characterization of new and drought stress responsive microRNAs in Populus euphratica. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:3765–3779. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding Y., Chen Z., Zhu C. Microarray-based analysis of cadmium-responsive microRNAs in rice (Oryza sativa) J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:3563–3573. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L., Wang T., Zhao M., Tian Q., Zhang W.H. Identification of aluminum-responsive microRNAs in Medicago truncatula by genome-wide high-throughput sequencing. Planta. 2012;235:375–386. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H.H., Tian X., Li Y.J., Wu C.A., Zheng C.C. Microarray-based analysis of stress-regulated microRNAs in Arabidopsis Thaliana. RNA. 2008;14:836–843. doi: 10.1261/rna.895308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding D., Zhang L., Wang H., Liu Z., Zhang Z., Zheng Y. Differential expression of miRNAs in response to salt stress in maize roots. Ann. Bot. 2009;103:29–38. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covarrubias A.A., Reyes J.L. Post-transcriptional gene regulation of salinity and drought responses by plant microRNAs. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collonnier C., Fock I., Kashyap V., Rotino G.L., Daunay M.C., Lian Y., Mariska I.K., Rajam M.V., Servaes A., Ducreux G., et al. Applications of biotechnology in eggplant. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. 2001;65:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doganlar S., Frary A., Daunay M.C., Lester R.N., Tanksley S.D. A comparative genetic linkage map of eggplant (Solanum melongena) and its implications for genome evolution in the solanaceae. Genetics. 2002;161:1697–1711. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.4.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller L.A., Solow T.H., Taylor N., Skwarecki B., Buels R., Binns J., Lin C., Wright M.H., Ahrens R., Wang Y., et al. The SOL Genomics Network: A comparative resource for solanaceae biology and beyond. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1310–1317. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniell H., Lee S.B., Grevich J., Saski C., Quesada-Vargas T., Guda C., Tomkins J., Jansen R.K. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Solanum bulbocastanum, Solanum lycopersicum and comparative analyses with other Solanaceae genomes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;112:1503–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu F., Eannetta N.T., Xu Y., Durrett R., Mazourek M., Jahn M.M., Tanksley S.D. A COSII genetic map of the pepper genome provides a detailed picture of synteny with tomato and new insights into recent chromosome evolution in the genus Capsicum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;118:1279–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0980-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu F., Eannetta N.T., Xu Y., Tanksley S.D. A detailed synteny map of the eggplant genome based on conserved ortholog set II (COSII) markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;118:927–935. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0950-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopalan R., Vaucheret H., Trejo J., Bartel D.P. A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3407–3425. doi: 10.1101/gad.1476406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fahlgren N., Howell M.D., Kasschau K.D., Chapman E.J., Sullivan C.M., Cumbie J.S., Givan S.A., Law T.F., Grant S.R., Dangl J.L., et al. High-throughput sequencing of Arabidopsis microRNAs: Evidence for frequent birth and death of MIRNA genes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szittya G., Moxon S., Santos D.M., Jing R., Fevereiro M.P., Moulton V., Dalmay T. High-throughput sequencing of Medicago truncatula short RNAs identifies eight new miRNA families. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:593. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morin R.D., Aksay G., Dolgosheina E., Ebhardt H.A., Magrini V., Mardis E.R., Sahinalp S.C., Unrau P.J. Comparative analysis of the small RNA transcriptomes of Pinus contorta and Oryza sativa. Genome Res. 2008;18:571–584. doi: 10.1101/gr.6897308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chi X., Yang Q., Chen X., Wang J., Pan L., Chen M., Yang Z., He Y., Liang X., Yu S. Identification and characterization of microRNAs from peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martínez G., Forment J., Llave C., Pallás V., Gómez G. High-throughput sequencing, characterization and detection of new and conserved cucumber miRNAs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo H., Kan Y., Liu W. Differential expression of miRNAs in response to topping in flue-cured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) roots. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song C., Wang C., Zhang C., Korir N.K., Yu H., Ma Z., Fang J. Deep sequencing discovery of novel and conserved microRNAs in trifoliate orange (Citrus trifoliata) BMC Genomics. 2010;11:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sunkar R., Zhu J.K. Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2001–2019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai X., Davis E.J., Ballif J., Liang M., Bushman E., Haroldsen V., Torabinejad J., Wu Y. Mutant identification and characterization of the laccase gene family in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:2563–2569. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y., Yan J., Kim I., Liu C., Huo K., Rao H. Rad4 regulates protein turnover at a postubiquitylation step. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:177–185. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pauluzzi G., Divol F., Puig J., Guiderdoni E., Dievart A., Périn C. Surfing along the root ground tissue gene network. Dev. Biol. 2012;365:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung M.Y., Vrebalov J., Alba R., Lee J., McQuinn R., Chung J.D., Klein P., Giovannoni J. A tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) APETALA2/ERF gene, SlAP2a, is a negative regulator of fruit ripening. Plant J. 2010;64:936–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koyama T., Furutani M., Tasaka M., Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:473–484. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Audic S., Claverie J.M. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai X., Zhao P.X. psRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W155–W159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.