Abstract

The fundamentally social nature of humans is revealed in their exquisitely high sensitivity to potentially negative evaluations held by others. At present, however, little is known about neurocortical correlates of the response to such social-evaluative threat. Here, we addressed this issue by showing that mere exposure to an image of a watching face is sufficient to automatically evoke a social-evaluative threat for those who are relatively high in interdependent self-construal. Both European American and Asian participants performed a flanker task while primed with a face (vs control) image. The relative increase of the error-related negativity (ERN) in the face (vs control) priming condition became more pronounced as a function of interdependent (vs independent) self-construal. Relative to European Americans, Asians were more interdependent and, as predicted, they showed a reliably stronger ERN in the face (vs control) priming condition. Our findings suggest that the ERN can serve as a robust empirical marker of self-threat that is closely modulated by socio-cultural variables.

Keywords: social-evaluative threat, culture, error-related negativity

INTRODUCTION

Both evolutionary and cultural considerations suggest that humans are highly attuned to their own conspecifics (Tomasello, 1999). This sensitivity is revealed in the fact that awareness of someone watching the self—or the awareness of social eyes—plays an important role in the regulation of one’s own behaviors (Kitayama et al., 2004; Na and Kitayama, 2011). For example, when exposed to a watching face, individuals become more prosocial (Haley and Fessler, 2005; Rigdon et al., 2009). Because self-regulation in social settings is often facilitated by knowing how others might evaluate the self, it stands to reason that at least for some people, mere exposure to social eyes might be sufficient to automatically evoke a concern about potentially negative social evaluations held by others (Leary, 1983; Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004). Such a concern (herein called social-evaluative threat) may increase vigilance for one’s errors on a task at hand. In the current work, we explored this hypothesis by using an electrophysiological signal of error monitoring called error-related negativity (ERN).

There is a general consensus in the literature that social belongingness is a fundamental human motive (Bowlby, 1988; Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Because positive social evaluations imply social acceptance, it should not come as any surprise that these evaluations are integral to psychological well-being (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Murray et al., 2003). Conversely, when one is socially rejected or negatively evaluated and, thus, one’s positive social image is threatened, a variety of adverse psychological and physiological reactions can follow. For example, a social-evaluative threat can lead to both a decrease in social self-esteem (Gruenewald et al., 2004) and an increase in physiological stress responses such as cortisol secretion (Dickerson et al., 2008) and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Kemeny and Gruenewald, 2000). It would seem reasonable, then, that people are sometimes highly vigilant of social-evaluative threats that might present themselves. Among many social cues, an image of a watching face may signal a potential threat of this kind, insofar as there is a good chance that the watching person observes and evaluates the self (Kitayama et al., 2004; Haley and Fessler, 2005; Rigdon et al., 2009).

Of course, this is not to say that all individuals are equally sensitive to social-evaluative threats posed by a watching face. Previous work suggests that some individuals may be more likely to draw on social evaluations such as ‘honor’ and ‘face’ in defining the self and maintaining positive self-identities. The degree to which one’s self and self-identity is defined relationally, in terms of its belongingness in a meaningful social relationship, is captured by interdependent self-construal (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). People who are high in interdependent self-construal are likely to rely heavily on social evaluations in developing and maintaining their positive self-identities. Conversely, people with independent self-construals are likely to define the self in terms of their own appraisals of the self rather than relying on evaluations held by others. Thus, it may be anticipated that those with interdependent (vs independent) self-construal will be more sensitive to social-evaluative threats (Kim and Markman, 2006). One important corollary of this analysis is that Asians may be more likely than European Americans to be sensitive to social-evaluative threats because the former tend to be more interdependent (and less independent) than the latter (Singelis, 1994; Oyserman et al., 2002).

The degree to which a social-evaluative threat is automatically evoked may be captured by a neurophysiological response called error-related negativity (ERN). The ERN refers to a sharp negative voltage deflection that occurs in response to error commission in choice response tasks (Falkenstein et al., 1991; Gehring et al., 1993). The ERN is assumed to index an early, automatic detection of unfavorable outcomes (Botvinick et al., 2004), which does not necessarily rely on conscious reflection (Amodio et al., 2004). Although the ERN is typically conceptualized as a marker of cognitive processing of error/conflict detection (Botvinick et al., 2001; Yeung et al., 2004), recent findings suggest that it can also reflect affective reactions such as a response to threat (Hajcak, 2012; Weinberg et al., 2012). For example, the magnitude of the ERN is positively correlated with a defensive startling response after errors, a common reaction to threatening stimuli (Hajcak and Foti, 2008). Moreover, both negative affectivity and behavioral inhibition system (BIS), which are implicated in the sensitivity to threat (Carver and White, 1994; Gray, 1994), are positively correlated with the ERN (Dikman and Allen, 2000; Luu et al., 2000; Boksem et al., 2006). As may be expected, when the source of negative arousal is misattributed to a benign external factor, the ERN is reduced (Inzlicht and Al-Khindi, 2012). Similarly, priming of religious belief systems is likely to reduce perceived threat and, as may be expected, it reduces the ERN amplitude (Inzlicht and Tullett, 2010).

In the present work, we used an image of a watching face as a social cue signaling a potential threat to the self. We presented this image as a priming stimulus on some trials of a flanker task while monitoring participants’ brain responses using electroencephalogram (EEG). If face priming were sufficient to automatically evoke a social-evaluative threat, thereby increasing vigilance for errors, especially for interdependent people, this should improve performance in the flanker task while increasing the ERN amplitude at the same time. We thus made the following three predictions.

Performance of the flanker task should be better in the face priming condition than in the control priming condition, but this improvement of task performance in the face (vs control) priming condition should be more pronounced for those higher in interdependent self-construal.

The ERN should be larger in magnitude in the face priming condition than in the control priming condition, but this increase of the ERN in the face (vs control) priming condition should be more pronounced for those higher in interdependent self-construal.

Asians would be more interdependent than European Americans. It would therefore follow that both the improvement of task performance and the increase of the ERN amplitude in the face (vs control) priming condition should be more pronounced for Asians than for European Americans.

METHOD

Participants

Thirty-seven undergraduates at the University of Michigan (18 males, Mage = 20.81, s.d.age = 2.39) participated in the study in exchange for $30. Nineteen were European Americans (10 males, Mage = 20.16, s.d.age = 1.68) and the remaining 18 were East Asians (8 males, Mage = 21.53, s.d.age = 2.87). All Asian participants were born in China, Korea or Japan spending no more than 9 years in USA. All participants were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Our preliminary analysis showed no gender effects; gender was therefore dropped in the following analysis.

Procedure

Upon arrival, participants were told that the study would test brain responses during a cognitive task. Following attachment of EEG electrodes, participants were given an arrowhead version of the Eriksen flanker task (Eriksen and Eriksen, 1974) in a dark, sound attenuated room. Participants were seated ∼60 cm from a 15 inch CRT color monitor.

The flanker task consisted of 30 blocks of 48 trials. Each trial involved the presentation of a priming stimulus, followed by target arrows. The 48 trials within each block varied in prime type [face, scrambled face or house, (3)] and arrowhead type [<<<<<, >>>>>, <<><< or >><>>, (4)], with four trials in each of the 12 (= 3 × 4) combinations. The order of the 48 trials was randomized within each block for each participant.

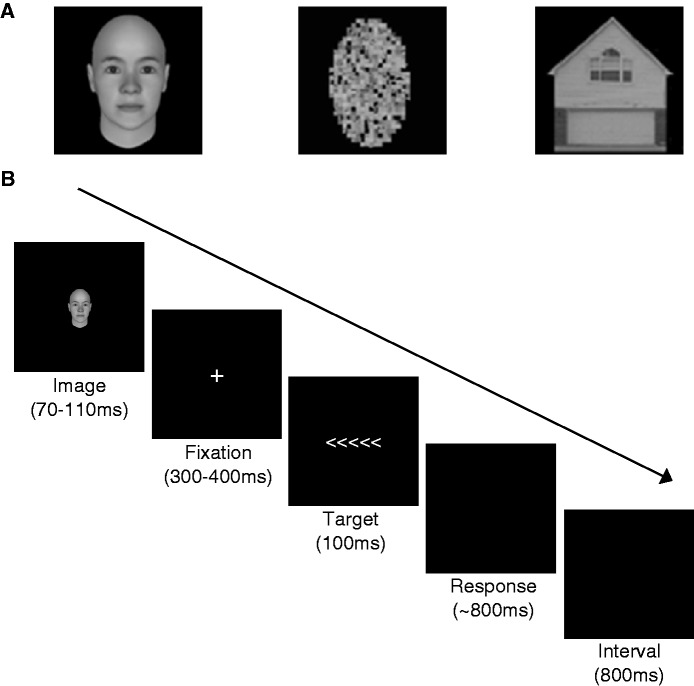

On each trial, participants were first presented with a priming stimulus (see Figure 1A for sample images) for an average of 90 ms (jittered between 70 and 110 ms). Each priming stimulus was presented at the center of the screen with a visual angle of 2.2 × 2.2°. The priming stimulus was followed by a fixation cross, which stayed on the screen for an average of 350 ms (jittered between 300 and 400 ms). The fixation cross was immediately followed by one of the four arrowhead sequences. Each arrowhead sequence occupied 0.4° of visual angle vertically and 2.2° horizontally. It was presented centrally for 100 ms in white on black background. Participants were instructed to press one of two designated keys with the left or right index finger in accordance with the direction of the center arrowhead. They were given a maximum of 800 ms to respond. Eight-hundred milliseconds after the response, the next trial started (see Figure 1B for trial structure). At the end of each block, a feedback screen was displayed. When the accuracy in a given block became higher (lower) than 90%, participants were encouraged to respond faster (more accurately) in the next block.

Fig. 1.

(A) Sample face, scrambled face and house image. (B) Schematic diagram illustrating sample stimuli.

Face images were created by FaceGen Modeller 3.3 (Singular Inversions Inc.). To eliminate any effects of in- vs out-group status of the priming faces, we created race-neutral morphed faces that included 50% Caucasian and 50% Asian faces. We scrambled the morphed face images to create scrambled face images. House images were adopted from Polk et al. (2007). The two control conditions (i.e. scrambled face and house) did not differ significantly in all analyses below, so they were subsequently combined.

Physiological recording and processing

The EEG was recorded with 64 electrodes placed according to the extended International 10/20-System in a nylon cap, and referenced to the left mastoid. The electro-oculogram (EOG) was recorded from additional channels at the outer canthi of both eyes and above and below the left eye. EEG and EOG signals were amplified with a band-pass of DC to 100 Hz by the BioSemi ActiveTwo system, and sampled with 512 Hz. All data were re-referenced to the averaged left and right mastoid, and re-sampled at 256 Hz. Response-locked ERP was obtained by extracting an epoch beginning 500 ms before the response and ending 1000 ms after the response. The data were baseline corrected by using 150–50 ms pre-response voltage. Trials with EEG recordings exceeding 500 μV were eliminated,1 and the EEG was corrected for ocular artifacts (Gratton et al., 1983). A low-pass filter with a half-amplitude cutoff at 30 Hz was applied. The EEG recordings for correct and incorrect responses were averaged separately. The ERN was quantified as the mean amplitude between 50 ms before and 50 ms after the incorrect response at the frontocentral midline electrode (FCz).

Post-experimental questionnaire

Next, participants filled out a 20-item self-construal scale that was composed of selected items from the scales by Singelis (1994) and Takata (1999) (Appendix 1). Participants were asked to rate how much they agree or disagree with each statement on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale yields separate scores for independent self-construal (αs = 0.60 and 0.68 for Asians and European Americans, respectively) and interdependent self-construal (αs = 0.79 and 0.57). We also assessed personality variables that are linked to the ERN. In particular, we assessed neuroticism by asking participants to rate their agreement for each of the 48 items (e.g. I often feel inferior to others, I often do things on impulse) on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO PI-R), Costa and McCrae, 1992; αs = 0.95 and 0.94]. Participants also completed the self-consciousness scale (Fenigstein et al., 1975), which was composed of three subscales: private self-consciousness (e.g. I’m always trying to figure myself out; αs = 0.78 and 0.80), public self-consciousness (e.g. I usually worry about making a good impression; αs = 0.63 and 0.79) and social anxiety (e.g. I feel anxious when I speak in front of a group; αs = 0.76 and 0.82). Participants indicated the extent to which each statement was characteristic of them on a 5-point scale (1 = extremely uncharacteristic, 5 = extremely characteristic). Means and standard deviations of the questionnaire measures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of the individual difference measures

| Post-experimental questionnaire measures | European Americans |

East Asians |

Cross-cultural comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | s.d. | M | s.d. | t-test | ||

| Independent self-construal | 4.06 | 0.40 | 3.21 | 0.45 | 5.98*** | |

| Interdependent self-construal | 3.32 | 0.41 | 3.80 | 0.42 | −3.45** | |

| Neuroticism | 122.05 | 26.23 | 140.53 | 25.48 | −2.14* | |

| Private self-consciousness | 3.58 | 0.62 | 3.41 | 0.50 | 0.88 | |

| Public self-consciousness | 3.61 | 0.66 | 3.64 | 0.48 | −0.15 | |

| Social anxiety | 2.68 | 0.80 | 3.44 | 0.64 | −3.11** | |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

RESULTS

Behavioral data

The post-experimental questionnaire showed that European Americans were more independent than Asians [4.06 vs 3.21, F(1,34) = 35.74, P < 0.001,  = 0.51] and Asians were more interdependent than European Americans [3.80 vs 3.32, F(1,34) = 11.92, P < 0.005,

= 0.51] and Asians were more interdependent than European Americans [3.80 vs 3.32, F(1,34) = 11.92, P < 0.005,  = 0.26]. Consistent with prior work (McCrae et al., 1998), Asians were significantly higher in neuroticism than European Americans [140.53 vs 122.05, F(1,34) = 4.57, P < 0.05,

= 0.26]. Consistent with prior work (McCrae et al., 1998), Asians were significantly higher in neuroticism than European Americans [140.53 vs 122.05, F(1,34) = 4.57, P < 0.05,  = 0.12]. The cultural groups did not differ in private self-consciousness (European Americans: 3.58 vs Asians: 3.41) and public self-consciousness [European Americans: 3.61 vs Asians: 3.64, Fs < 1, n.s.]. However, Asians were high in social anxiety than European Americans [3.44 vs 2.68, F(1,34) = 4.57, P < 0.05,

= 0.12]. The cultural groups did not differ in private self-consciousness (European Americans: 3.58 vs Asians: 3.41) and public self-consciousness [European Americans: 3.61 vs Asians: 3.64, Fs < 1, n.s.]. However, Asians were high in social anxiety than European Americans [3.44 vs 2.68, F(1,34) = 4.57, P < 0.05,  = 0.12].

= 0.12].

We also found that face priming had no effect on either accuracy (88.93 and 88.62 in the face priming and the control priming conditions, respectively) or response time on error trials [273.40 and 270.93 ms, respectively, Fs < 1, n.s.], although, on correct trials, response time was shorter in the face priming condition than in the control priming condition [350.97 vs 352.82 ms, F(1,36) = 11.87, P < 0.01,  = 0.25].

= 0.25].

Our analysis implies that face priming would pose a social-evaluative threat to those with interdependent self-construal. When threatened this way, people would become more vigilant to their errors and try to avoid them. To test this analysis, we captured the degree to which face priming improved task performance by subtracting the accuracy in the face priming condition from the accuracy in the control priming condition to yield a measure of the face priming effect. Positive values indicate an improved performance in the face (vs control) priming condition. Next, as in prior work in this area (Kitayama et al., 2009; Na and Kitayama, 2011), we subtracted the independence score from the interdependence score to yield a single index of interdependence (vs independence), because the two subscales were negatively correlated (r = −0.59, P < 0.001). Positive values indicate greater interdependence (vs independence). This procedure was considered necessary to address potential acquiescence bias that can result from the fact that the self-construal scale has no reverse-coded items. One Asian participant was excluded from this analysis because she did not complete the booklet that contained the self-construal scale.

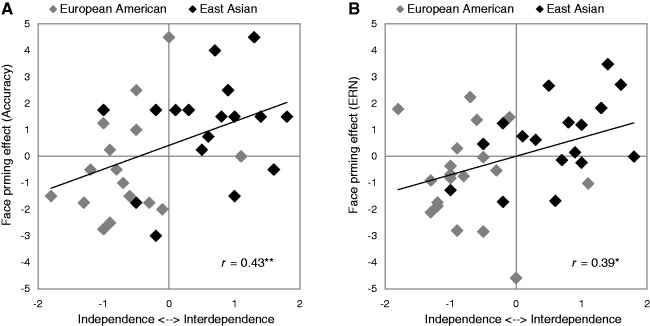

As predicted, the face priming effect on accuracy was significantly correlated with interdependent self-construal (r = 0.43, P < 0.01). As shown in Figure 2A, as a function of interdependent self-construal, performance tended to improve in the face (vs control) priming condition. This is in line with the hypothesis that interdependent individuals are threatened by social eyes and, as a consequence, they become more vigilant for their own errors in the task and tried to avoid them. The correlation between the face priming effect on accuracy and interdependent self-construal remained significant when trait social anxiety, private and public self-consciousness and neuroticism were controlled (r = 0.38, P < 0.05) (see Table 2 for zero-order correlations between the face priming effect and the personality measures).

Fig. 2.

The scatterplots with interdependent (vs independent) self-construal on the x-axis and the face priming effect (A: accuracy, B: ERN) on the y-axis. The x-axis shows the difference score between interdependent self-construal and independent self-construal (i.e. interdependent self-construal—independent self-construal). Interdependent (vs independent) self-construal was positively correlated with both face priming effects (accuracy: r = 0.43, P < 0.01; ERN: r = 0.39, P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations between the face priming effects, self-construal and personality measures

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Face priming effect on accuracy | −0.03 | −0.35* | 0.43*** | 0.43*** | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.35* | |

| 2. | Face priming effect on the ERN | −0.36* | 0.33* | 0.39* | 0.13 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.15 | ||

| 3. | Independent self-construal | −0.59*** | −0.92*** | −0.47*** | 0.20 | −0.01 | −0.55*** | |||

| 4. | Interdependent self-construal | 0.86**** | 0.61*** | 0.21 | 0.47*** | 0.57*** | ||||

| 5. | Interdependence vs independence | 0.59*** | −0.02 | 0.24 | 0.63*** | |||||

| 6. | Neuroticism | 0.37* | 0.45*** | 0.56*** | ||||||

| 7. | Private self-consciousness | 0.75*** | 0.07 | |||||||

| 8. | Public self-consciousness | 0.18 | ||||||||

| 9. | Social anxiety |

Note. Interdependence vs independence indicates the difference score subtracting independent self-construal from interdependent self-construal. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

As shown in Figure 2A, the relationship between interdependent self-construal and the face priming effect on accuracy was similar within each cultural group (rs = 0.25 and 0.29 for Asians and European Americans, respectively), although it was no longer significant when analyzed separately within each culture, most likely due to reduced sample size. As predicted by the fact that Asians were significantly more interdependent (vs independent) than European Americans [0.59 vs − 0.74, F(1,34) = 32.68, P < 0.001,  = 0.49], the face priming effect was significantly greater for Asians than for European Americans [1.01 vs −0.36, F(1,35) = 4.91, P < 0.05,

= 0.49], the face priming effect was significantly greater for Asians than for European Americans [1.01 vs −0.36, F(1,35) = 4.91, P < 0.05,  = 0.12]. Indeed, the face priming effect was significantly positive, indicating that the incidental exposure to a face (vs control) stimulus improved task performance for Asians [F(1,17) = 5.21, P < 0.05,

= 0.12]. Indeed, the face priming effect was significantly positive, indicating that the incidental exposure to a face (vs control) stimulus improved task performance for Asians [F(1,17) = 5.21, P < 0.05,  = 0.23]. This effect was absent for European Americans [F(1,18) < 1, n.s.].2

= 0.23]. This effect was absent for European Americans [F(1,18) < 1, n.s.].2

There was no comparable effect in response time; the face priming effect on response time was neither correlated with interdependent self-construal nor predicted by cultural backgrounds of the participants.

ERN

When people are threatened during the flanker task and thus become vigilant of their own errors, they may be expected to show an increased neural response to those errors. We thus calculated the degree to which face priming increased the magnitude of the ERN by subtracting the face priming condition ERN from the control priming condition ERN. Positive values indicate larger ERNs in the face (vs control) priming condition. As Figure 2B illustrates, the face priming effect on the ERN was significantly predicted by interdependent self-construal (r = 0.39, P < 0.05). As interdependent self-construal increased, the ERN in the face (vs control) priming condition also increased. This provides support for the hypothesis that interdependent people are threatened by social eyes, which in turn increases neural reactions to errors they make. The correlation between the face priming effect on the ERN and interdependent self-construal remained significant when trait social anxiety, private and public self-consciousness and neuroticism were controlled (r = 0.40, P < 0.05).

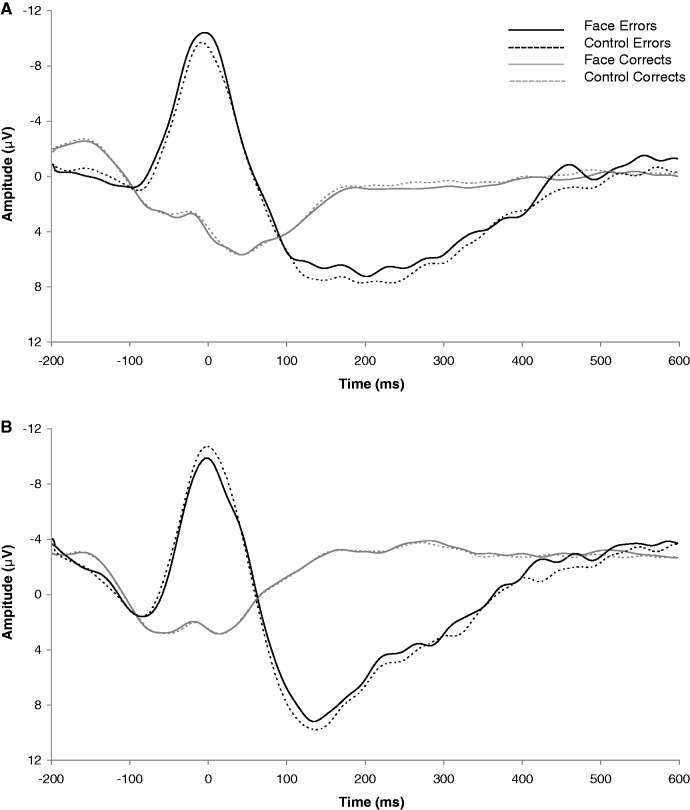

As shown in Figure 2B, however, when the relationship between interdependent self-construal and the face priming effect on the ERN was analyzed separately within each cultural group, it was marginally significant for Asians (r = 0.47, P < 0.06), but not for European Americans (r = −0.13, n.s.). It is not clear why the correlation was negligible for the European American group. One possible reason is that the range of interdependence was relatively narrow for European Americans, which might have made it more difficult to detect the relationship with the face priming effect on the ERN. Nevertheless, in support of the proposition that the face priming effect on the ERN increases as a function of interdependent self-construal, this effect was significantly larger for Asians than for European Americans [0.70 vs −0.73, F(1,35) = 7.36, P = 0.01,  = 0.17]. Indeed, the face priming effect was significantly larger than zero for Asians [F(1,17) = 4.20, P = 0.05,

= 0.17]. Indeed, the face priming effect was significantly larger than zero for Asians [F(1,17) = 4.20, P = 0.05,  = 0.20]. Curiously, this effect was reversed, albeit marginally, for European Americans [F(1,18) = 3.36, P = 0.08,

= 0.20]. Curiously, this effect was reversed, albeit marginally, for European Americans [F(1,18) = 3.36, P = 0.08,  = 0.16]. Pertinent waveforms are displayed in Figure 3. As can be seen, the ERN magnitude was larger in the face priming condition than in the control priming condition for Asians. However, the pattern was reversed for European Americans. They showed greater ERN amplitudes in the control priming condition than in the face priming condition. Although this reversal was only marginally significant (see above), it became significant once we controlled for the condition difference in accuracy in the analysis of the ERN [F(1,17) = 6.45, P < 0.05,

= 0.16]. Pertinent waveforms are displayed in Figure 3. As can be seen, the ERN magnitude was larger in the face priming condition than in the control priming condition for Asians. However, the pattern was reversed for European Americans. They showed greater ERN amplitudes in the control priming condition than in the face priming condition. Although this reversal was only marginally significant (see above), it became significant once we controlled for the condition difference in accuracy in the analysis of the ERN [F(1,17) = 6.45, P < 0.05,  = 0.28]. We will return to this curious reversal effect in Discussion section.

= 0.28]. We will return to this curious reversal effect in Discussion section.

Fig. 3.

Error-related negativity (ERN) and correct-response negativity (CRN) waveforms at FCz for East Asians (A) and European Americans (B).

As noted above, interdependent self-construal was significantly higher for Asians than for European Americans (0.59 vs −0.74). Moreover, for Asians we found that self-construal was correlated, albeit marginally, with the face priming effect on the ERN. We thus estimated what face priming effect Asians might show if their interdependence score were equal to the average score for the current sample of European Americans (= −0.74). This estimate of face priming effect for Asians (= −1.04) was virtually identical to the mean face priming effect for European Americans (=−0.73, F < 1).3 This pattern is consistent with the supposition that Asians showed the face priming effect that was opposite of the effect shown by European Americans because they were predominantly more interdependent (vs independent).

Given our assumption that both improved performance and increased ERN represent a response to face priming, it might seem sensible to anticipate that the two effects should be tightly correlated. Surprisingly, however, the correlation between the two face priming effects turned out to be virtually zero (r = −0.03, n.s.).

DISCUSSION

Face, social-evaluative threat and the self

Face is a prominently social cue, which can signal that the self is being observed by others. Social observation like this implies social evaluation, which in turn can evoke a social-evaluative threat to the self, especially for those who are interdependently oriented. Our work is the first in the literature to test this analysis with both a behavioral measure (task performance) and a neurocortical response (ERN). Both of them are thought to capture an enhanced vigilance for one’s errors on a task at hand. To the extent that mere exposure to a watching face is sufficient to evoke a social-evaluative threat to the self, task performance should improve and, simultaneously, the ERN should be amplified. We showed, as predicted, that these effects do occur, but importantly they do so only to those who define themselves in interdependent terms.

More specifically, we first assessed the degree to which performance in the flanker task improved in the face priming (relative to the control priming) condition. As expected, the face priming effect on accuracy was significantly correlated with interdependent (vs independent) self-construal. This correlation remained unchanged when pertinent personality variables such as neuroticism, private and public self-consciousness and social anxiety were controlled. Second, as also predicted by the hypothesis that Asians are more interdependent than European Americans, we observed that the face priming effect on accuracy was significantly positive for Asians, indicating their improved task performance in the face (vs control) priming condition. This effect, however, completely vanished for European Americans. Third, when a comparable analysis was carried out on the ERN, the face priming effect was significantly correlated with interdependent (vs independent) self-construal. This correlation remained statistically significant when the relevant personality variables were controlled. Fourth, as also predicted, the face priming effect was significantly positive for Asians, meaning that face priming increased Asians’ ERN magnitude, relative to control primes. Curiously, this face priming effect on the ERN was reversed for European Americans with the ERN weaker in the face (vs control) priming condition.

Task performance and error monitoring: distinct coping strategies?

It is noteworthy that the face priming effect was observed, not only in the behavioral task performance, but also in the error-related brain activity. The ERN is a neural signal that is known to occur automatically even outside of one’s awareness (Amodio et al., 2004) with close connections to subcortical reward processing systems (Holroyd and Coles, 2002; Münte et al., 2008). The current finding that such a rapid brain processing was modulated by cultural backgrounds of the participants as a function of interdependent (vs independent) self-construal may indicate the existence of neural mechanisms that are recruited automatically whenever the social self is threatened. Furthermore, it demonstrates that social environments play a critical role in regulating not only high-level psychological processes such as behavioral tendencies but also low-level neural activities such as error processing.

Given this line of analysis, however, it would seem puzzling that we observed that the two measures of social-evaluative threats (task performance and the ERN) did not correlate with one another. We speculate that this finding might indicate an important individual difference in strategies used to deal with social-evaluative threats. When confronted with such a threat, people might vary in both the extent to which they would work harder on a task at hand (as revealed in improved task performance) and the extent to which they would monitor their errors more closely (as revealed in enhanced ERN amplitude). The near-zero correlation we observed between the face priming effect in task performance and the comparable effect in ERN might imply that the propensities to use one or the other strategy to deal with the threat are nearly independent of one another. In this interpretation, the performance measure and the ERN measure might be conceptualized as indices of active and defensive coping styles, respectively (Roth and Cohen, 1986; Aldwin, 1999). Future work should follow up this possibility. For example, this analysis would receive support if it could be shown that the active coping is related to social adjustment while the defensive coping is not.

Face priming effect among European Americans

While our data are generally consistent with the theoretical analysis presented earlier, it raises some new questions. One such important question concerns the European American responses to face priming. Remember we anticipated that the face priming effect would be weaker for European Americans because they are relatively less interdependent. The result from the performance measure was consistent with this prediction. However, unexpectedly, the face priming effect was significantly reversed for the ERN measure; European Americans showed even greater ERN amplitudes in the control priming condition than in the face priming condition.

Two observations suggest that this reversal must be interpreted with caution. First, no comparable effect was evident in the analysis of the performance measure and second, the observed reversal of the face priming effect on the ERN became statistically significant only when the condition difference in accuracy was statistically controlled. Nevertheless, this effect could indicate that for those with independent selves, social eyes might automatically initiate motivation to counter any evaluation apprehension, supposedly because such apprehension could expose the vulnerability of the self to social evaluations, thus compromising the sense of the self as independent and autonomous. Such defensive mechanisms, if operative, might diminish any vigilance to one’s errors on the task at hand. This might explain why an exposure to such eyes reduced the ERN amplitude for European Americans. This issue must be further examined in future work.

The issue surrounding the European American response to watching faces is further complicated by a recent finding by Hajcak et al. (2005). These researchers examined effects of social observation on the ERN magnitude. Specifically, in their study, the experimenter stood right next to the participants who performed a flanker task. Furthermore, the participants had been explicitly informed that the experimenter would be evaluating their performance. Thus, evaluation apprehension was explicitly induced. Under this condition, the participants showed a reliably increased ERN relative to a control condition where they performed the task in a private setting. Because the participants who were tested are likely to be predominantly European Americans, we may suggest that even independent selves feel threatened, thereby producing large error signals, when evaluation apprehension is explicitly activated by a social observer.

Thus, what distinguishes interdependent selves from independent selves may lie in the fact that interdependent selves are more sensitive to subtle social cues implying a social-evaluative threat, such that they automatically experience evaluation apprehension when they are merely ‘seen’ by others. Consistent with this analysis, Ishii et al.’s (2010) report, also with an ERP as their dependent variable that interdependent people become especially sensitive to emotional vocal tones (which often convey interpersonal attitudes; Zuckerman et al., 1982; Ambady et al., 1996), when exposed to schematic faces that would appear to be watching them.

Self-threat and the ERN

In the current work, we reasoned that for those with interdependent selves, social eyes are self-threatening because they evoke social-evaluative concerns. Because of the threat, people increase vigilance to their own errors in a task at hand. According to this analysis, the ERN is a proxy for perceived self-threat. This of course is not to say that cognitive functions of conflict monitoring and error detection, which are often ascribed to the ERN (Botvinick et al.., 2001; Yeung et al., 2004) are unimportant. To the contrary, affective and motivational processes are likely to intensify such cognitive functions that do exist (Hajcak, 2012; Inzlicht and Al-Khindi, 2012; Kitayama and Park, 2012; see Weinberg et al., 2012 for a review). Future work should more closely examine interactions between the cognitive and the affective or motivational functions of the ERN to achieve a better understanding of mechanisms underlying error processing.

Although the current work focused exclusively on a social-evaluative threat experienced by interdependent selves, we do not wish to imply that independent selves are immune from any self-threat. To the contrary, previous work strongly suggests that independent selves tend to experience a strong threat to the self when positive qualities of one’s internal features such as abilities and personality traits are questioned (Miller and Ross, 1975; Campbell and Sedikides, 1999). Independent selves may well show an increased ERN under such conditions. Another type of threatening situation happens when individuals anticipate to be negatively evaluated by other people because of their membership in a stigmatized group. This state of stereotype threat (Steele et al., 2002) may also produce an increased ERN. Future work addressing these possibilities might demonstrate that the magnitude of the ERN can be taken as a proxy of threat-in-general to the self.

CONCLUSION

Our findings can be located squarely at the intersection of social and cognitive neuroscience and cultural psychology. They therefore contribute to the emerging interdisciplinary field of cultural neuroscience (Han and Northoff, 2008; Kitayama and Park, 2010; Kitayama and Uskul, 2011; Chiao, 2011). Using various ERP components, including P300 (Lewis et al., 2008) and N400 (Goto et al., 2010; Ishii et al., 2010), researchers have observed sizable cultural differences in brain responses. So far, however, much of this evidence is confined to contextual processing, with Asians shown to be more holistic in attention, as compared to European Americans. The present work provides novel evidence that the ERN can be used as a neural correlate of a social-evaluative threat. Moreover, our evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that interdependent people are quite sensitive to such threat when seen by others. Last, but not least, along with other related studies with face stimuli (Grasso et al., 2009; Sui et al., 2009), the current work indicates that automatic evaluations of a watching face are already inseparably intertwined with a network of neural processing that is attuned to culturally unique contingencies of social life (Kitayama and Park, 2010; Kitayama and Uskul, 2011).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation grant (BCS 0717982) and a National Institute of Aging grant (RO1 AG029509-01).

We thank Yukiko Uchida for her contribution in developing a version of the self-construal scale we used in the current work.

APPENDIX 1

Table A1.

Twenty-item self-construal scale

| Independence | |

|---|---|

| 1. | I always try to have my own opinions. (T) |

| 2. | I am comfortable with being singled out for praise or rewards. (S) |

| 3. | The best decisions for me are the ones I made by myself. (T) |

| 4. | In general I make my own decisions. (T) |

| 5. | I act the same way no matter who I am with. (S) |

| 6. | I am not concerned if my ideas or behavior are different from those of other people. (T) |

| 7. | I always express my opinions clearly. (T) |

| 8. | Being able to take care of myself is a primary concern for me. (S) |

| 9. | I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects. (S) |

| 10. | I do my own thing, regardless of what others think. (S) |

| Interdependence | |

| 11. | I am concerned about what people think of me. (T) |

| 12. | In my own personal relationships I am concerned about the other person’s status compared to me and the nature of our relationship. (T) |

| 13. | I think it is important to keep good relations among one’s acquaintances. (T) |

| 14. | I avoid having conflicts with members of my group. (T) |

| 15. | When my opinion is in conflict with that of another person’s, I often accept the other opinion. (T) |

| 16. | I respect people who are modest about themselves. (S) |

| 17. | I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of the group I am in. (S) |

| 18. | I often have the feeling that my relationships with others are more important than my own accomplishment. (S) |

| 19. | I feel my fate is intertwined with the fate of those around me. (S) |

| 20. | Depending on the situation and the people that are present, I will sometimes change my attitude and behavior. (T) |

The self-construal scale was composed of selected items from the Singelis self-construal scale (Singelis, 1994) and the Takata’s scale (Takata, 1999). The scale has 10 items measuring independence (five from the Singelis scale and five from the Takata’s scale) and 10 items measuring interdependence (four from the Singelis scale and six from the Takata’s scale). In the current work, we hypothesized that individuals with interdependent (vs independent) self-construal would be more sensitive to social-evaluative threats. While the Singelis scale is commonly used in the literature, it does not cover the content domain of evaluation apprehension. The Takata scale, developed and relatively more commonly used in Japan, does so. Therefore, we supplemented the Singelis scale with selected items from the Takata’s scale to develop an expanded version of the self-construal scale and used it in the current work. The Takata scale (available in Japanese) was translated into English by a Japanese–English bilingual. Back-translation was used to ensure semantic equivalence.

Footnotes

1The rejection rate was very low in all conditions (mean rejection rate = 6.38%, median rejection rate = 4.06%), and did not differ across two cultural groups in the two experimental conditions, F’s < 1. The number of error trials included in the analysis of the ERN was also no different across two cultural groups (Asians: M = 79.42, s.e.m = 6.08; European Americans: M = 73.15, s.e.m. = 5.92), F(1,35) < 1. This also did not significantly interact with prime type, F < 1.

2The pattern here, showing a cultural influence on interdependence, which in turn leads to the face priming effect on accuracy, implies a mediation of the cultural difference on the face priming effect by interdependence. This interpretation of the data, however, should be espoused with caution because the implied mediation fell short of the conventional level of statistical significance; the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval does include zero (−0.028, 0.001).

3It may be hypothesized that culture influences interdependence, which in turn enhances the face priming effect on the ERN. This implied mediation, however, was not significant [95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (−0.655, 1.812)], because the correlation between interdependence and the face priming effect on the ERN was negligible among European Americans.

REFERENCES

- Aldwin CM. Stress, Coping, and Development: An Integrative Approach. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ambady N, Koo J, Lee F, Rosenthal R. More than words: linguistic and nonlinguistic politeness in two cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:996–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, Harmon-Jones E, Devine PG, Curtin JJ, Hartley SL, Covert AE. Neural signals for the detection of unintentional race bias. Psychological Science. 2004;15:88–93. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boksem MA, Tops M, Wester AE, Meijman TF, Lorist MM. Error-related ERP components and individual differences in punishment and reward sensitivity. Brain Reseach. 2006;1101:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review. 2001;108(3):624–52. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Cohen JD, Carter CS. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WK, Sedikides C. Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: a meta-analytic integration. Review of General Psychology. 1999;3:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY. Cultural neuroscience: visualizing culture-gene influences on brain function. In: Decety J, Cacioppo J, editors. Handbook of Social Neuroscience. UK: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 742–61. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of lab research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:355–91. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Mycek PJ, Zaldivar F. Negative social evaluation, but not mere social presence, elicits cortisol responses to a laboratory stressor task. Health Psychology. 2008;27:116–21. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikman ZV, Allen JJ. Error monitoring during reward and avoidance learning in high- and low-socialized individuals. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:43–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception and Psychophysics. 1974;16:143–9. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein M, Hohnsbein J, Hoormann J, Blanke L. Effects of crossmodal divided attention on late ERP components. II. Error processing in choice reaction tasks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1991;78:447–55. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(91)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:522–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MGH, Meyer DE, Donchin E. A neural system for error detection and compensation. Psychological Science. 1993;4:385–90. [Google Scholar]

- Goto SG, Ando Y, Huang C, Yee A, Lewis RS. Cultural differences in the visual processing of meaning: detecting incongruities between background and foreground objects using the N400. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5(2–3):242–53. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso DJ, Moser JS, Dozier M, Simons R. ERP correlates of attention allocation in mothers processing faces of their children. Biological Psychology. 2009;81:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MGH, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55:468–84. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Personality dimensions and emotion systems. In: Ekman P, Davidson RJ, editors. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Acute threat to the social self: shame, social self-esteem, and cortisol activity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:915–24. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000143639.61693.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G. What we’ve learned from mistakes: insights from error-related brain activity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21(2):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Foti D. Errors are aversive: defensive motivation and the error-related negativity. Psychological Science. 2008;19:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Yeung N, Simons RF. On the ERN and the significance of errors. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:151–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley KJ, Fessler DMT. Nobody’s watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evoluation and Human Behavior. 2005;26:245–56. [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Northoff G. Culture-sensitive neural substrates of human cognition: a transcultural neuroimaging approach. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2008;9:646–54. doi: 10.1038/nrn2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd CB, Coles MGH. The neural basis of human error processing: reinforcement learning, dopamine, and the error-related negativity. Psychological Review. 2002;109(4):679–709. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Al-Khindi T. ERN and the placebo: a misattribution approach to studying the arousal properties of the error-related negativity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012;141:799–807. doi: 10.1037/a0027586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Tullett AM. Reflecting on God: religious primes can reduce neurophysiological response to errors. Psychological Science. 2010;21:1184–90. doi: 10.1177/0956797610375451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Kobayashi Y, Kitayama S. Interdependence modulates the brain response to word-voice incongruity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5(2–3):307–17. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny ME, Gruenewald TL. Affect, cognition, the immune system and health. In: Mayer EA, Saper CB, editors. The Biological Basis for Mind Body Interactions. Vol. 122. New York: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Markman AB. Differences in fear of isolation as an explanation of cultural differences: evidence from memory and reasoning. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:350–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park J. Cultural neuroscience of the self: understanding the social grounding of the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5(2–3):111–29. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park J. Error Related Brain Activity Reveals Self-Centric Motivation: Culture Matters. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park H, Sevincer AT, Karasawa M, Uskul AK. A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:236–55. doi: 10.1037/a0015999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Snibbe AC, Markus HR, Suzuki T. Is there any “free” choice? Self and dissonance in two cultures. Psychological Science. 2004;15(8):527–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Uskul AK. Culture, mind, and the brain: current evidence and future. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:419–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1983;9:371–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RS, Goto SG, Kong LL. Culture and context: East Asian American and European American differences in P3 event-related potentials and self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(5):623–34. doi: 10.1177/0146167207313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu P, Collins P, Tucker DM. Mood, personality, and self-monitoring: negative affect and emotionality in relation to frontal lobe mechanisms of error monitoring. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2000;129:43–60. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.129.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–53. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Yik MSM, Trapnell PD, Bond MH, Paulhus DL. Interpreting personality profiles across cultures: bilingual, acculturation, and peer rating studies of Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1041–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Ross M. Self-serving biases in attribution of causality: fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:213–25. [Google Scholar]

- Münte TF, Heldmann M, Hinrichs H, et al. Necleus accumbens is involved in human action monitoring: evidence from invasive electrophysiological recordings. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2008;1:1–6. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.011.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Griffin DW, Rose P, Bellavia GM. Calibrating the sociometer: the relational contingencies of self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:63–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na J, Kitayama S. Trait-based person perception is culture-specific: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychological Science. 2011;22(8):1025–32. doi: 10.1177/0956797611414727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk TA, Park J, Smith MR, Park DC. Nature versus nurture in ventral visual cortex: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of twins. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(51):13921–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4001-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon ML, Ishii K, Watabe M, Kitayama S. Minimal social cues in the dictator game. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2009;30:358–67. [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Cohen LJ. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist. 1986;41:813–9. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;20:580–91. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer S, Aronson J. Contending with group image: the psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 37. New York: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sui J, Liu CH, Han S. Cultural difference in neural mechanisms of self-recognition. Social Neuroscience. 2009;4(5):402–11. doi: 10.1080/17470910802674825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata T. Nihon bunka niokeru sogodokuritsusei-sogokyochosei no hattatsu katei: hikaku bunkateki, odan shiryo niyoru jisshoteki kento [Development process of independent and interdependent self-construal in Japanese culture: cross-cultural and cross-sectional analyses] Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;47:480–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Riesel A, Hajcak G. Integrating multiple perspectives on error-related brain activity: the ERN as a neurobehavioral trait. Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36:84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung N, Botvinick M, Cohen JD. The neural basis of error-detection: conflict monitoring and the error-related negativity. Psychological Review. 2004;111:931–59. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Amidon MD, Bishop SE, Pmerantz SD. Face and tone of voice in the communication of deception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;32:347–57. [Google Scholar]