Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Diabetes is one of the major concerns in the third millennium, affecting more people every day. The prevalence of this disease in Iran is reported to be high (about 7.7%). The most important method to control this disease and prevent its complications is self-care. According to various studies, this method has not found its proper place among patients with diabetes due to several reasons. The present study was aimed at determining the relationship between social support, especially family support, and self-care behavior of diabetes patients.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a narrative review in which the relevant papers of cross-sectional, cohort, clinical trial, and systematic review designs were selected using databases and scientific search engines such as PubMed, ProQuest, SCOPUS, and Elsevier, with the keywords diabetes, social support, and self-care. Moreover, Persian papers were selected from MEDLAB and IRANMEDEX databases and through searching the websites of original research papers published in Iran. All the papers published from 1990 to 2011 were reviewed.

Results:

The results of the study indicated that the status of self-care and social support in patients with diabetes was not favorable. All the studied papers showed that there was a positive relationship between social support and self-care behavior. Also, some studies pointed to the positive effect of social support, especially family support and more specifically support from the spouse, on controlling blood sugar level and HbA1c.

Conclusion:

As social support can predict the health promoting behavior, this concept is also capable of predicting self-care behavior of patients with diabetes. Therefore, getting the family members, especially the spouse, involved in self-care behavior can be of significant importance in providing health care to patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes, self-care, social support

INTRODUCTION

Currently, diabetes is known as one of the major public health concerns in the third millennium and is the fifth main mortality cause in the world.[1] This disease kills 4 million people every year, which is 9% of the deaths all over the world.[2] In Iran, a national study which investigated the risk factors of non-contagious diseases estimated the prevalence of diabetes as 7.7% in 2008.[3]

Today, this disease is being paid more attention due to its high prevalence, imposed costs on health systems, and various negative effects on the patients.[4] Suffering from chronic complications of diabetes leads to the decrease in life expectancy and increase in death, imposes high economic burden on the person, family, and society, and affects the life quality of the person and his/her family.[5] Thus, many researchers believe that diabetes belongs to the person and his/her family[6,7] as suffering from this as a chronic disease disturbs the person's family life and future prospects,[8] threatens their personal independence, and generates a feeling of being different from others.[9]

In this regard, self-care is one of the most fundamental strategies in diabetes which can control the disease,[10] and it highly depends on the will of the person for performing self-care and having self-care behaviors.[11] This strategy includes: Following the recommended diet, doing regular physical activity, checking blood sugar, and consuming the medication regularly.[12]

Nevertheless, the results of some studies have indicated that the self-care situation of diabetic patients is not at an appropriate level and the patients have low self-care ability.[13,14] The results of the studies by Dailey showed the non-optimum self-care situation among diabetic patients.[15,16] In Iran, the research conducted by Seyedeh Roghayyeh Jafarian,[17] Elham Shakibazadeh,[18] Mohammad Ali Morowati,[19] and Parvin Baghaei[20] revealed the same situation, and the study by Alireza Shahab Jahanloo demonstrated that only 27% of diabetic patients follow the recommended dietary behaviors.[21]

Although health care providers are responsible for orienting diabetes control programs, their attempts often do not lead to desirable results. The findings have shown that in spite of making the patients aware, healthy function (self-care) does not occur, so some researchers believe that increasing patients’ knowledge of the disease is not sufficient per se for beginning and maintaining self-care behaviors and assuring the long-term control.[22,23]

Therefore, many quality studies have measured the reason for lack of implementing optimum self-care among the patients with diabetes,[24,25] and have introduced various individual, social, and environmental sources as the obstacles for the optimum self-care of diabetics. Some studies have also indicated that demographic factors like increased age decrease self-care.[26,27] Moreover, socioeconomic factors like less education,[28,29] low economic level,[28,30] and social factors like weak individual and family relationships[26] seriously impede self-management process.

As diabetes is a chronic disease which requires extensive behavioral changes and adherence to a complex diet, social support is considered as one of the influential and important factors for performing self-care and for adherence to the treatment and disease control[31] which can facilitate self-care behaviors and compatibility with the disease.[32] On the other hand, a major part of the care for this disease is done at home and inside the family.[33] Therefore, diabetes is sometimes called a family disease because its control and demands influence all family members.[34] Thus, social support, especially family support, can be a vital component in the successful control of diabetes. This paper attempted to determine the relationship and effect of social support, especially family support, on the self-care behaviors in diabetic patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

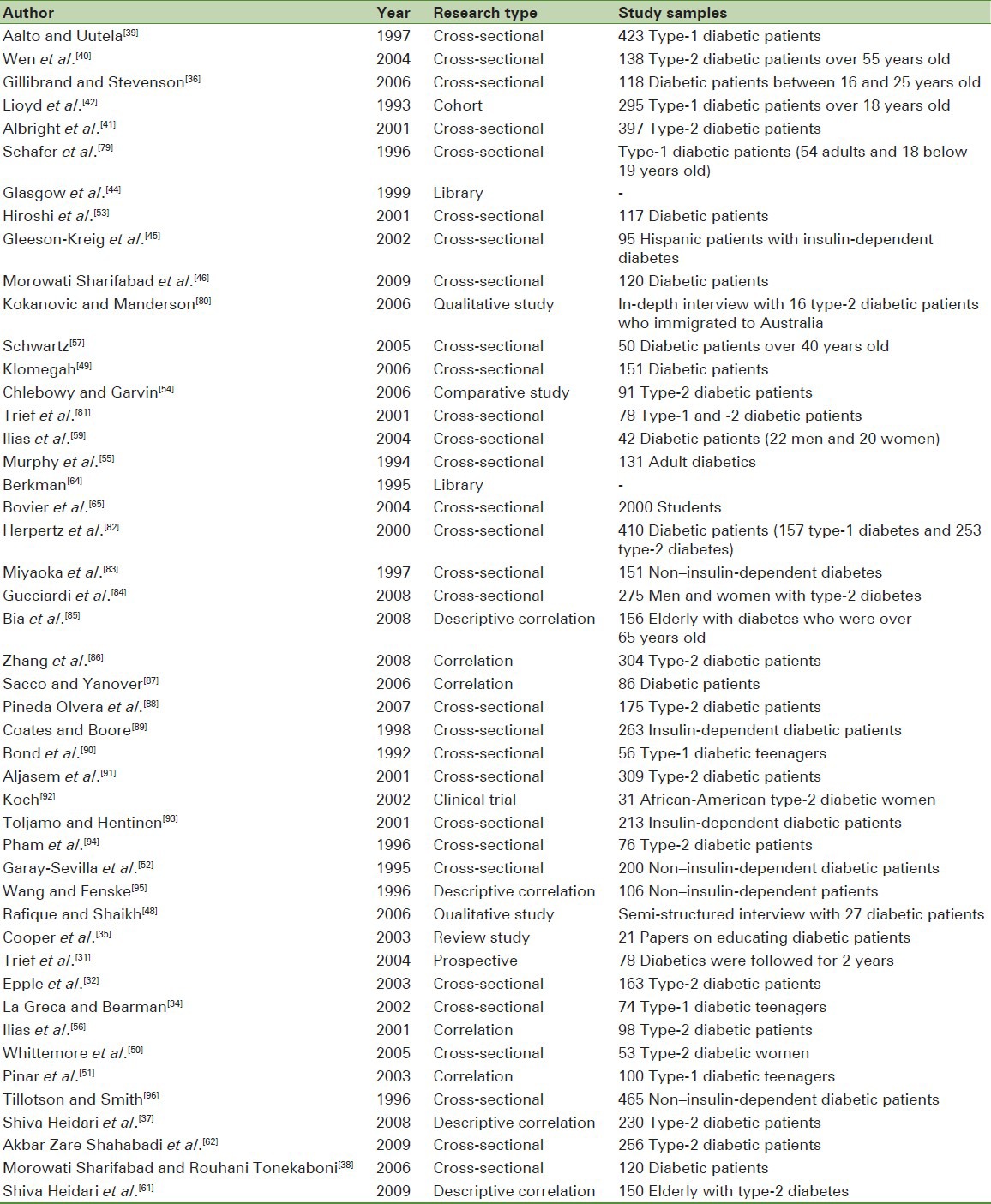

This narrative review study was conducted using scientific search engines and information databanks like PubMed, ProQuest, SCOPUS, and Elsevier, and keywords like self-care, diabetes, social support, and family support in order to select studies with cross-sectional, cohort, clinical trial, correlation, and qualitative designs. Moreover, Persian papers were selected from MEDLIB and IRANMEDEX information databanks and by searching websites of internal research journals. The time range of the reviewed articles was from 1990 until the end of 2011. Some investigated papers are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The papers investigated in this paper

RESULTS

The findings of other studies showed that the perceived social support situation is not at an optimum level among diabetic patients; the research by Cooper et al. demonstrated that diabetic patients need others’ support.[35] Gillibrand's study revealed that social support in diabetic patients is not at an optimum level.[36] The studies conducted in Iran have demonstrated that this support is not at an optimum level among diabetic patients; studies by Shiva Heidari[37] and Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad[38] can be referred to in this regard.

As far as the relationship between social support and self-care behaviors is concerned, the following results can be mentioned: In the study by Alato which used the developed health belief pattern, it was determined that adherence to the self-care diet had a relationship with social support.[39] Wen, who investigated family support, diet, and sports among elderly American Mexican men suffering from type-2 diabetes, observed that with the increase in this support, adherence to diet and sports increased.[40] Gillibrand's research[36] and Albroght's study[41] demonstrated a positive significant relationship between social support and self-care behaviors. They reported that social and family fields are strongly accompanied by self-care behaviors, especially diets.

Lioyd et al. also studied psychosocial factors related to glycemic control. In their study, as social support increased for adherence to the self-care recommendations, this kind of adherence increased too.[42] In the study by Vijan on 446 urban and rural patients, one of the obstacles reported by patients was with regard to observing dietary recommendations, which was due to lack of family and social support. In that study, those who received more support from their families easily observed and adhered to diets.[43] Furthermore, Galsgow stated that family support is the strongest determining factor for following treatment diet among type-2 diabetic patients.[44]

Other studies have demonstrated that social support from diabetic patients affects their tendency toward doing self-care activities.[45,46] Marzili's research showed that family support had high effect on following diet and sports in diabetic patients.[47] Additionally, Rafique's study in Pakistan showed that affective stress and lack of social support are among the self-care obstacles for diabetic patients.[48] A study by Klomegah indicated that if family members, friends, and others observe a healthy diet, it is easier for the patients to adhere to a healthy diet.[49] In their study on 76 type-2 diabetic patients which lasted for 2 years, Trief et al. noticed that quality of marital status (intimacy and compatibility) is a predictor of adherence to self-care dimensions (diet, sports, and doctor's advice).[31]

Whittemore reported that the most important predicting factor for the metabolic control and diet adherence among type-2 diabetic patients is support and self-confidence.[50] The study by Pinar on diabetic patients showed that factors like intimacy among family members, existence or lack of existence of conflict in the family, and current affective status of the family can affect the self-efficiency of patients and can lead to increase of self-efficiency and decrease of stress in the family.[51]

Garay-Sevilla found that adherence to diet and medication was related to the duration of illness and family and social support.[52] Moreover, Hiroshi showed that social support and its source are influential in the treatment and control of diseases.[53] Also, according to the study by Fleeson-Kreig, the more the receiving support from spouse and others, the more faithful the patient would be in terms of adherence to self-care activities.[45] In fact, the study by Chlebowy observed no significant correlation between social support and behavior.[54]

Murphy also showed that although family support leads to the improvement of self-care programs in diabetic patients, adherence to self-care programs does not automatically lead to more decrease in blood sugar.[55] Nevertheless, Ilias et al. conducted a study on 98 type-2 diabetic patients and concluded that optimal level of glycosylated hemoglobin had a relationship with the social support received from the family.[56] Moreover, Schwartz[57] and Dai[58] observed a relationship between social support and blood sugar control. The study by Ilias[59] and Glasgow[44] showed that family support decreased and controlled blood sugar.

Gholamreza Sharifirad conducted a study in Iran which demonstrated that lack of social and family support was among the obstacles for observing the diet, as mentioned by the patients.[60] Shiva Heidari studied diabetic elderly and found a significant relationship between social support and blood sugar control in that those patients who received more support from their family network could optimally control their blood sugar.[61] Moreover, the study by Akbar Zare Shahabad indicated a significant direct relationship between the level of perceived social support and the level of adherence to self-care activities.[62] Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad also demonstrated that perceived social support had a positive and significant correlation with self-care in that supporting family behaviors predicted 9.1% of self-care changes. In his study, general perceived social support explained 6.4% of changes in the self-care behaviors.[38] Another study by Shiva Heidari showed a significant inverse relationship between family support and HbA1c. In her study, family support led to the improvement in the control of blood sugar among patients and a significant relationship was found between family support and the number of family members.[61]

DISCUSSION

Social support is one of the emotion-oriented coping mechanisms with the potential power for influencing life quality.[63] Studies have shown a significant relationship between health and social support, so people who receive higher social support have better health.[64,65] Some studies have shown that social support leads to the improvement in health functions and even immunity performance.[66,67,68] Other studies on AIDS, indicators of body immunity, and on hemodialysis patients demonstrated a relationship between social support and these diseases in terms of their control and treatment.[69,70,71]

The findings of the researchers have shown that perceiving social support can prevent the emergence of non-optimum physiological complications in the person, increase the level of self-care and self-confidence, and positively affect physical, mental, and social conditions; thus, it evidently leads to the increase in the performance and improvement of life quality.[72] In general terms, it should be stated that social support has a great impact on human health.[73,74]

Diabetes disturbs daily performance and social activities of the patient, changes his/her capability for performing normal roles and responsibilities, and creates new roles for him/her. The relationship with the spouse, children, parents, sister, brother, friends, and other members of the social network is not like before. These people more or less depend on others and can support others to a lesser degree. Therefore, their personal interactions with others are limited and they may be isolated in the society. Thus, their need for social support increases. Social support affects the control of diabetes through two processes: a) direct effect of social support via behaviors related to health, such as encouraging healthy behaviors, and b) moderating effect of social support which helps in the moderation of acute and chronic nervous pressure on health and increase of compatibility with the nervous pressure of the diabetes disease.[75]

Different definitions have been presented for the term social support. Social support has been defined as the level of enjoying love, accompaniment, and attention of family members, friends, and other people.[75] In fact, social support is “the facilities provided by others for the person.” Moreover, this concept is considered as “the knowledge which leads the person toward believing that others respect him/her, are interested in him/her, and consider him/her as valuable, dignified, and a person who belongs to a social network of relations and commitment.”[76] Social support is defined as the functional content of relationships, which can be categorized in the following four groups of support behaviors:

Affective support including feeling sympathy, love, trust, and attention, which has a strong relationship with health

Financial support including service and financial assistance

Information support as recommendations, advice, and information used by the person for being faced with the problems

Evaluative support as accessing useful information for self-evaluation.

Although these four functions are different in conceptual terms, they are not independent from each other in practice.[76]

In this regard, family is the first and the most important supportive source which sacrifices itself for providing care for its members. Each family attempts to constantly support the person, even if that person is injured and cannot compensate for it. Moreover, spouses are usually the first people who assist as supportive sources in critical conditions. Strong relationships with family, sister, brother, or friends do not make up for the lack of strong relationship with spouse and cannot prevent from depression and stress in patients at the time of life problems. Other studies have introduced spouses as the most important supportive sources in crises and stressful conditions of life.[77]

The use of incorrect support behaviors (like reproaching him/her for the lack of timely implementation of treatment programs) by close people in dealing with the patients has an inverse effect on self-care program implementation. An even more interesting point is that when others use positive reinforcing behaviors (such as accompanying or encouraging) to force the patients to follow the treatment program, better results are obtained and the patient could better perform the treatment program. Nagging and reproaching about lack of performing self-care programs not only does not lead to the increase of these behaviors, but also can lead to the feeling of despair among patients; as a result, they decrease self-care program implementation. Families should consider the point that providing and eating the food that is not appropriate for the diabetic patients can in fact lead them toward avoiding their treatment diet. For instance, eating food which is not a part of the patients’ diet by family members is among the considerable points in the non-supportive family behaviors.

CONCLUSION

In the health improvement model, Pender considered family support as interpersonal effects which can predict health improvement behaviors. In studies which were done based on the health improvement model, 75% supported interpersonal effects as a predicting factor of the behavior.[78] It has been observed that both general social support and diabetes-related support are in correlation with the adherence to self-care behaviors in diabetic patients. Since close family support and relationship have a special position in Iranian culture, it seems that presenting sufficient information with regard to the disease to the people who are close to the patient and their involvement and cooperation in the treatment and control processes can facilitate the work of treatment team and help the patient in reaching the utmost life quality and health.[96]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Roglic G, Unwin N, Mathers C, Tuomilehto J, Nag S, Connolly V, et al. The burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: Realistic estimates for the year 2000. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2130–35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Foundation. The International Diabetes Federation welcomes adoption of WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. 2004. [Last accessed on 2009 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/home/indexcfm .

- 3.Esteghamati A, Gouya MM, Abbasi M, Delavari A, Alikhani S, Alaedini F, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the adult population of Iran: National Survey of Risk Factors for Non Communicable Diseases of Iran. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:96–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson JA. Critical social theory approach to nursing care of adolescents with diabetes. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1999;22:143–52. doi: 10.1080/014608699265248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Empowerment and self- management of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2004;22:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heisler M. Helping your patients with chronic disease: Effective physician approaches to support selfmanagement. Semin Med Pract. 2005;8:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: Reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telford K, Kralik D, Koch T. Acceptance and denial: Implications for people adapting to chronic illness: Literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:457–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oki S, Hoshi T. Empowerment process of Self-help Group: A Qualitative Study of Patient Group Members of Crohn and Colitis. Compr Urban Stud. 2004;83:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siguroardottir AK. Self-care in diabetes: Model of factor affecting self-care. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:301–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer J, Kozewski W, Jones G, Staneu Kogstrand K. The use of interviewing to Assess Dietetic Internship Preceptors needs and perce-ptions. J Amer Dietetic Asso-ciation. 2006;106:A58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDowell J, Courtney M, Edwards H, Shortridge- Baggett L. Validation of the Australian/English version of the Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005;11:177–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HJ, Park KY, Park HS. Self-care activity, Metabolic control, and cardiovascular risk factors in accordance with the levels of depression of clients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35:283–91. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmood K, Aamir AH. Glycemic control status in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:323–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dailey George. A timely transition to insulin: Identifying type 2 diabetes patients failing oral therapy. Formulary. 2005;40:114–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dailey George. Fine-Tuning therapy with basal insulin for optimal glicemic control diabetes: A review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:2007–14. doi: 10.1185/174234304X15183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jafarian Amiri SR, Zabihi A, Babaieasl F, Eshkevari N, Bijani A. Self care behaviors in diabetic patients referring to diabetes clinics in Babol City, Iran. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2010;12:72–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shakibazadeh E, Rashidian A, Larijani B, Shojaeezadeh D, Forouzanfar MH, Karimi Shahanjarini A. Perceived barriers and self-efficacy: Impact on self-care behaviors in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Fac Nurs Midwifery. 2010;15:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morowati Sharifabad M, Rouhani Tonekaboni N. Social support and self-care behaviors in diabetic patients referring to Yazd Diabetes Research Center. ZJRMS. 2008;9:275–84. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baghaei P, Zandi M, Vares Z, Masoudi Alavi N, Adib-Hajbaghery M. Self care situation in diabetic patients referring to Kashan Diabetes Center, in 2005. Feyz Kashan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2008;12:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahanloo AS, Ghofranipour F, Vafaei M, Kimiagar M, Heydarnia AR, Sobhani A. Health Belief Model constructs measured with HbA1c in diabetic patients with good control and poor. J Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2008;12:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susan LN. Recommendation for Healthcare system and Self-Management Education interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality from diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:10–4. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heisler Michele, Piette John D, Spencer Michael, Kieffer Edie, Vijan Sandeep. The relationship between knowledge of rec15793179ent HbA1c values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:816–22. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons D, Lillis S, Swan J, Haar J. Discordance in perceptions of barriers to diabetes care between patients and primary care and secondary care. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:490–5. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdoli S, Ashktorab T, Ahmadi F, Parvizi S. Barriers to and facilitators of empowerment in people with diabetes. IJEM. 2009;5:455–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberti H, Boudriga N, Nabli M. Factors affecting the quality of diabetes care in primary health care centres in Tunis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;68:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams AS, Mah C, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Barton MB, Ross-Degnan D. Barriers to self-monitoring of blood glucose among adults with diabetes in an HMO: A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Darbinian JA, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Self monitoring of blood glucose: Language and financial barriers in a managed care population with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:477–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman D, Smith J. Can patient self-management help explain the SES health gradient? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162086599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piette J, Heisler M, Wagner T. Problems paying outof- pocket costs among older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:384–91. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trief PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Britton KD, Weinstock RS. The relationship between marital quality and adherence to the diabetes care regiment. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:148–54. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epple C, Wright AL, Joish VN, Bauer M. The role of active family nutritional support in Navajos’ type-2 diabetes metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2829–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw BA, Gallant MP, Jacome MR, Spokane LS. Assessing sources of support for diabetes self- care in urban and rural underserved communites. J Community Health. 2006;31:393–412. doi: 10.1007/s10900-006-9018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.La Greca AM, Bearman KJ. The diabetes social support questionnaire family version: Evaluating adolescent's diabetes- specific support from family members. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:665–76. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper HC, Booth K, Gill G. Patient's perspectives on diabetes health care education. Health Educ Res Theory Pract. 2003;18:192–206. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillibrand R, Stevenson J. The extended health belief model applied to the experience of diabetes in young people. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:155–69. doi: 10.1348/135910705X39485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidari SH, NooriTajer M, Shirazi F, Sanjari M, Shoghi M, Salemi S. Relationship between family support and glycemic control in patients with type-2 diabetes. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2008;8:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morowati Sharifabad M, Rouhani Tonekaboni N. Social support and self-care behaviors in diabetic patients referring to Yazd Diabetes Research Center. Zahedan J Res Med Sci, J Zahedan Univ Med Sci. 2008;9:275–84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aalto AM, Uutela A. Glycemic control, self_care behaviors, and Psychosocial factors among insulin treated diabetics: A test of an extended health belief model. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:191. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0403_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen LK, Shepherd MD, Parchman ML. Family support, diet, and exesice among older Mexican Americans with type-2 diabetes. Diabetes Edue. 2004;30:980–93. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK, Rrnest Investigators. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type-2 diabetes: An rrnest study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lioyd CE, Wing RR, Orchard TJ, Becker DJ. Psychosocial correlates of glycemic control: Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications (EDC) Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1993;21:187–95. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(93)90068-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijan S, Stuart NS, Fitzgerald JT, Ronis DL, Hayward RA, Slater S, et al. Barriers to following dietary recommendations in type-2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:32–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Kaplan RM, Vincor F, Smith LN, Norman J. If diabetes is a health problem, why not treat it as one. A population-based approach to chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 1999;2:159–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02908297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gleeson-Kreig J, Bernal H, Wooley S. The role of social support in the self-management of diabetes mellitus among a Hispanic population. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19:215–22. doi: 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2002.19310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morowati Sharifabad MA, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad S, Baghaiani Moghadam MH, Rouhani Tonekaboni N. Relationships between locus of control and adherence to diabetes regimen in a sample of Iranians. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30:27–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.60009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marzilli G, Cossege W. The effects of social support on eating behavior in patients whit diabetes. [Last accessed on 2005 May 5]. Available from: http://www.insulin-pumpersorg/textlib/psyc353.pdf .

- 48.Rafique GH, Shaikh F. Identifying needs and barriers to diabetes education in patients with diabetes. J Pak Assoc. 2006;56:347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klomegah RY. The influence of social support on the dietary regimen of people with diabetes. Sociation Today. 2006;4:104–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whittemore R, D’Eramo Melkus G, Grey M. Metabolic control, self-management and psychosocial adjustment in women with type-2 diabetes. J Clin Nurse. 2005;14:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinar R, Arslanoglu I, Isgüven P, Cizmeci F, Gunoz H. Self-efficacy and its interrelation with family environment and metabolic control in Turkish adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2003;4:168–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garay-Sevilla ME, Nava LE, Malacara JM, Huerta R, Díaz de León J, Mena A, et al. Adherence to treatment and social support in Patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 1995;9:81–6. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(94)00021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiroshi O, Kenji K, Narutsugu E, Hiroshi Y, Haruko K. Effect of social support on treatment in diabetes. J Osaka Med Coll. 2001;60:103–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chlebowy DO, Garvin BJ. Social support, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations: Impact on self-care behaviors and glycemic control in Caucasian and African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32:777–86. doi: 10.1177/0145721706291760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy DJ, Williamson PS, Nease DE. Supportive family member of diabetic adults. Fam Prac Res J. 1994;14:323–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ilias I, Hatzimichelakis E, Souvatzoglou A, Anagnostopoulou T, Tselebis A. Perception of family support is correlated with glycemic control in Greeks with diabetes mellitus. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:929–30. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz AJ. Master of Gerontological Studies [thesis] Florida: Miami University; 2005. Perceived social support and self-management of diabetes among adults age 40 years and over. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai YT. Washington, U.S: University of Washington; 1995. The effect of family support, Expectation of Filial Piety, and Stress on Health Consequences of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ilias I, Tselebis A, Theotoka I, Hatzimichelakis E. Association of perceived family support through glycemic control in Greek patient managing diabetes with diet alone. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharifirad GH, Entezari MS, Kamran A, Azadbakhat L. Effectiveness of nutrition education to patients with type-2 diabetes: The health belief model. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2008;7:379–86. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heidari SH, NooriTajer M, Hoseini F, Inanlo M, Golgiri F, Shirazi F. Geriatric family support and diabetic type-2 glycemic control. Salmand Iran J Ageing. 2008;3:573–80. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zare Shahabadi A, Hajizade Meimandi M, Ebrahimi Sadrabadi F. Influence of social support on treatment of Type II diabetes in Yazd. J Shaheed Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2010;18:277–83. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ersoy-Kart M, Guldu O. Vulnerability to stress, perceived social support, and coping styles among chronic hemodialysis patients. Dial Transplant. 2005;34:662–71. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:245–54. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bovier PA, Chamot E, Perneger TV. Perceived stress, internal resources, and social support as determinants of mental health among young adults. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:161–70. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015288.43768.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyazaki T, Ishikawa T, Iimori H, Miki A, Wenner M, Fukunishi M, Kawamura N. Relationship between perceived social support and immune function. Stress Health. 2003;19:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 67.McNicholas SL. Social support and positive health practices. West J Nurs Res. 2002;2:772–87. doi: 10.1177/019394502237387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang HH, Wu SZ, Liu YY. Association between social support and health outcomes: A metaanalysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003;19:345–51. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70436-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Massoudi M, Farhadi A. Family social support rate of HIV positive individuals in Khorramabad. Med J Lorestan Univ Med Sci. 2006;7:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alipur A. The relationship of social support with immune parameters in healthy individuals: Assessment of the marn effect model. Iran J Psychiatry Clinl Psychol. 2006;12:134–9. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zamanzadeh V. Relationship between quality of life and social support in hemodialysis patients in Imam Khomeini and Sina Educational Hospital of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Med J Tabriz Univ Med Sci. 2007;29:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu DSF, Lee FT, Woo J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C) Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:135–43. doi: 10.1002/nur.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uchino BN, Uno D, Holt-lunstad J. Social support, physiological processes, and health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;8:141–8. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Antonucci TC, Ajrouch DJ, Janevic M. Socioeconomic status, social support, age, and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:390–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adams MH, Bowden AG, Humphrey DS, McAdams LB. Social support and health-promotion lifestyle of rural women. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2000;1:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Auslander WC. Environment influence on diabetes management: Family, health system and community context. In: Haire- Joshu D, editor. Management of diabetes mellitus. Perspective of care across the lifespan. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. pp. 513–26. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: Reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol. 1996;15:135–48. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. 4th ed. USA: Prentice Hall; 2002. Health-promotion in nursing practice; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schafer LC, McGaul KD, Glasgow RE. Supportive and non- Supportive family behavior: Relationship to adherence and metabolic control in persons with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1986;9:179–85. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kokanovic R, Manderson L. Social support and self-management of type-2 diabetes among immigrant Australian women. Chronic Illness. 2006;2:291–301. doi: 10.1177/17423953060020040901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trief PM, Himes CL, Orendorff F, Weinstock RS. The marital relationship and psychosocial adaptation and glycemic control of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1384–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herpertz R, Krämer-Paust R, Paust B, Schulze Schleppinghoff F, Best R, Bierwirth S, et al. Patient with diabetes mellitus: Psychostress & use of psychosocial support: A multi center study. Med Klim (munich) 2000;95:369–77. doi: 10.1007/s000630050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyaoka Y, Miyaoka H, Motomiya T, Kitamura SI, Asai M. Impac of sociodemographic & Diabetes-related characteristic on depressive diabetes-related characteristic on depressive state among non-Insulin dependent diabetic pateints. Psychaitry Celin. 1997;51:203–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gucciardi E, Wong SC, Demelo M, Amaral L, Stewart DE. Charactristic of men and women with diabetes. Observation during patient's initial visit to a diabetes education center. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:219–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bia YL, Chiou CP, Chang YY, Lam HC. Correlates of depression in type-2 diabetic elderly patients: A correlation study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang CX, Chen YM, Chen WQ. Association of psychosocial factors with anxiety and depressive symptoms in Chinese patients with type-2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sacco WP, Yanover T. Diabetes and depression. The role of social support and medical symptoms. J Behave Med. 2006;29:523–31. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pineda Olvera AE, Stewort SM, Galindo L, Stephan J. Diabetes, depression and metabolic control in latinas. Cultur Divers Ethinic Minor Psychol. 2007;13:225–31. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coates VE, Boore JR. The influence of psychological factors on the self-management of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:528–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bond GG, Aiken LS, Somerville SC. The health belief model and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol. 1992;11:190–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aljasem LI, Peyrot M, Wissow L, Rubin RR. The impact of barriers and self efficacy on self care behaviors in type-2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27:393–404. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koch J. The role of exercise in the African- American woman with type-2 diabetyes mellitus: Application of the health belief model. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14:126–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toljamo M, Hentinen M. Adherence to self-care and social support. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:618–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pham DT, Fortin F, Thibaudeau MF. The role of the Health Belief Model in amputees’ selfevaluation of adherence to diabetes self-care behaviors. Diabetes Educ. 1996;22:126–32. doi: 10.1177/014572179602200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang CY, Fenske MM. Self-care of adults with non- insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Influence of family and friends. Diabetes Educ. 1996;22:465–70. doi: 10.1177/014572179602200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tillotson L, Smith S. Locus of control, social support, and adherence to the diabetes regimen. Diabetes Educ. 1996;22:133–8. doi: 10.1177/014572179602200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]