Abstract

Context:

Various studies have shown that quality of life in women after menopause undergoes radical changes. Several factors such as psycho-social factors are associated with the quality of life during menopausal period.

Aims:

The present study surveyed the factors associated with quality of life of postmenopausal women in Isfahan, based on Behavioral Analysis Phase of PRECEDE model.

Settings and Design:

This cross-sectional study was conducted through stratified random sampling among 200 healthy postmenopausal women in Isfahan in 2011.

Subjects and Methods:

Data were collected by two valid and reliable questionnaires (one to assess the quality of life and the other to survey the factors associated with the Behavioral Analysis Phase of PRECEDE model). Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 18) and analytical and descriptive statistics.

Results:

Pearson correlation indicated a positive and significant correlation between the quality of life and attitude toward menopause, perceived self-efficacy, and enabling and reinforcing factors, but there was no significant relationship between the quality of life and knowledge about menopause. Also, the quality of life in postmenopausal women had significant correlation with their age, education level, marital status, and employment status.

Conclusion:

Based on the present study, attitude, perceived self-efficacy, perceived social support, and enabling factors are associated with the quality of life in postmenopausal women. So, attention to these issues is essential for better health planning of women.

Keywords: Behavioral analysis, menopause, PRECEDE model, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Today, health systems have found their most important programs on family health basis. Women have a key role in family health and are the main model of education and promotion of healthy lifestyle to the next generation. Although men and women have common health problems, women, due to their physiological conditions, are facing special issues. One of these issues is the menopausal transition period, during which estrogen reduction creates additional problems for women.[1] During this period, the body is experiencing hormonal changes, the fertility reduces, and the risk of physical and mental changes increases.[2] The average age of menopause in natural women is between 42 and 58 years, and the median is 51.4 years.[2] Yet, the average age of menopause in Iranian studies is lower and equal to 47.8 years.[1] Since life expectancy of 48.3 years in the year 1900 increased to 79.8 years in 2001, women spend over one-third of their life in postmenopausal period.[3] Regarding this issue, considering the quality of life of women in postmenopausal period will be very important for public health.[4] Quality of life is a subjective component of well-being and one of the indicators proposed for measuring health.[5] The World Health Organization (WHO) defined quality of life as “an individual's perception of his/her position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which he/she lives, and in relation to his/her goals, expectations, standards and concerns.”[6] Several studies in Iran and other countries mostly indicate a negative effect of menopause on the quality of life in women.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] Golyan Tehrani's study showed that 38.3% of postmenopausal women in Tehran suffered from severe hot flashes, 43% suffered from severe anxiety, and 40% considered themselves highly irritable. In this study, about 30% of postmenopausal women reported diminished sexual desire during menopause.[10] Blumel states that postmenopausal women are 10.6, 3.5, 5.7, and 3.2 times more likely than other women to have vasomotor, social-psychological, physical, and sexual disorders, respectively, which leads to lower quality of life of these women.[13] Since one of the goals of Health-for-All Policy for the twenty-first century is improving the quality of life, the use of a model as a framework to identify the factors that lowered the quality of life in postmenopausal women and weakened their health status, and also designing educational programs to improve the quality of life of postmenopausal women appears to be essential. Reviewing resources indicates the efficiency of PRECEDE model in the prediction of quality of life of different groups of people.[16,17,18] PRECEDE model, introduced by Green and Kreuter in 1970, considers many factors that shape health status and give clear interpretation of these factors.[19] In fact, during the fourth phase of this model (Educational and Ecological Assessment), potential factors effecting health problems are determined and classified in the three categories of Predisposing, Enabling, and Reinforcing factors.[20] Predisposing factors are those that provide fundamental motivation or reason for the behavior and are considered as individual benefits.[20] In this study, knowledge, attitude, and perceived self-efficacy were considered as predisposing factors. Enabling factors are those that enable a person's desires or wish to be realized and become final or operative, and include skills, resources, and barriers, which can enable or impede environmental and behavioral changes.[20] In this study, access to information resources, holding training classes, having appropriate diet during menopause, skill to do exercises needed for controlling complications of this period, the daily problems, and access to financial resources were considered as enabling factors. Reinforcing factors including the rewards and feedback received from others following adoption of a behavior may encourage or discourage continuation of the behavior.[20] In this study, postmenopausal women's perception of support received from relatives was considered as the reinforcing factor. Unfortunately, in Iran, women's health programs and services have been limited to specific topics such as issues of pregnancy and family planning so far, while other health needs of women, including menopausal transition period issues, have been neglected.[1] Thus, the present paper evaluated the quality of life in postmenopausal women and some of the influencing factors, hoping that it can be a guide for better planning of educational and counseling programs associated with improving the quality of life in postmenopausal women. We hypothesized that lower predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors would be associated with poorer quality of life in postmenopausal women.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present cross-sectional study was designed as a descriptive-analytic study conducted with 200 healthy postmenopausal women of Isfahan in 2011. Stratified random sampling was performed according to population size. Since according to the statistical center of Iran, about 90% of 40-65-year-old women in Isfahan are housewives and the rest are retired, in this study, 90% of sample size were selected from housewives and 10% from retired women. These people were accessed through care centers and retirement centers of the city. The included participants were women between 1 to 10 years of menopause. Meanwhile, women who had a history of hormone therapy during the past 6 months, hysterectomy, non-Iranian nationality, and severe physical and psychological disorders were excluded.

Data were collected using two questionnaires as follows. The first questionnaire was a researcher-made questionnaire based on Behavioral Analysis Phase of the PRECEDE model, developed in four sections. The first section of the questionnaire included 19 questions about personal background, age, age of menopause, educational level, occupation, etc., The second section of the questionnaire was devoted to assessing predisposing factors in the form of 18, 9, and 13 questions about knowledge, attitude, and perceived self-efficacy, respectively. Knowledge assessing questions were designed in two ways. The first three questions about knowledge of symptoms, complications, and ways to control these complications were multiple-choice questions and the rest were true/false questions. In this section, every correct answer was scored with one point and every wrong answer with zero point. Attitude assessment including nine questions was designed in the form of three-choice Likert scale (agree, neutral, disagree). Positive attitude was scored with two points and negative attitude with zero point. Perceived self-efficacy assessment including 13 questions was designed in the form of five-choice Likert scale. The highest score for perceived self-efficacy was four and the lowest score was zero. The second section of the questionnaire was devoted to assessing enabling factors that were measured in form of six yes/no questions. Each “yes” answer scored one and each “no” answer scored zero. Finally, the fourth section of the questionnaire was devoted to assessing the reinforcing factors in the form of four questions. These questions measured postmenopausal women's perceptions of support received from their relatives. These were yes/no questions. Each “yes” answer scored one and each “no” answer scored zero. It is noteworthy that the mean scores in all sections of the questionnaire were expressed as percentage. For determining the content validity of the questionnaire, the opinions of eight health education experts and three reproductive health specialists were used. To determine the reliability, a pilot study was conducted among 30 women in the target study population and the reliability of this questionnaire was approved using Cronbach's alpha test (α = 0.76).

The second questionnaire was a standard questionnaire to measure the quality of life of postmenopausal women, which was developed during another study in Isfahan, based on a standard questionnaire on the quality of life in postmenopausal women (last edition: Jacqueline 2004 from the Women's Health Society of Toronto, Canada MENQOL) and American Menopause Society Questionnaire (UQOL) [Wolf (2002)]. After determining the validity and reliability (α = 0.70), it was used in this study. This questionnaire includes 72 questions and evaluates the quality of life of postmenopausal women in five psychological, physical, social, sexual, and physical activities domains. The data were collected with the consent of postmenopausal women in a completely private environment by interview. Then, the data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 18), descriptive statistics, independent t-test, Spearman and Pearson correlation tests.

RESULTS

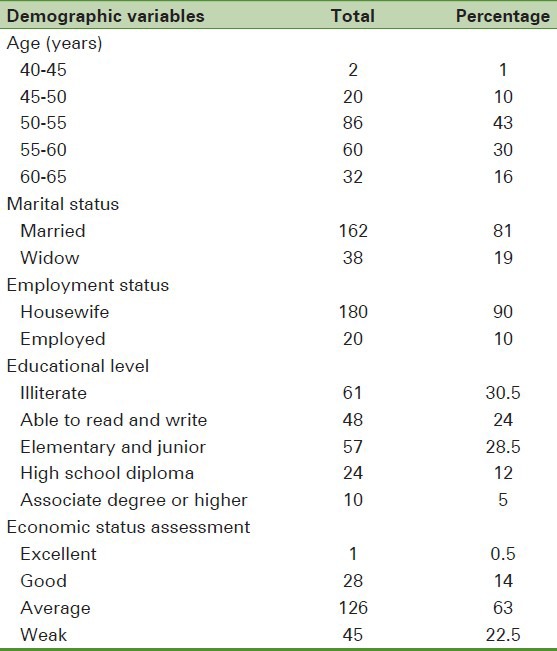

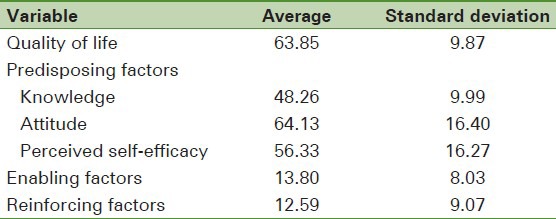

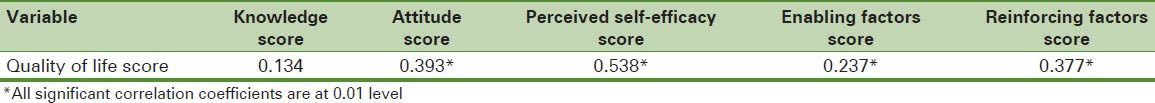

The average age of the subjects was 55.74 ± 4.77 years, and the average age of menopause was 50.20 ± 3.56 years. The majority of subjects (63%) had average socioeconomic status, and more than half of the sample (56%) had average health status. Our criterion for determining the socioeconomic status and health status of women was their subjective view. Other demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows the average and standard deviation for scores of quality of life and Behavioral Analysis Phase of the PRECEDE model (out of 100). As can be seen, the mean score for quality of life in postmenopausal women was 63.85 ± 9.87. In the factors section of Behavioral Analysis Phase of PRECEDE model, attitude toward the menopause had the highest mean score (63.13 ± 13.40) and reinforcing factors had the lowest mean score (12.59 ± 9.07). The results showed that in predisposing factors section, the quality of life in postmenopausal women had a significant statistical correlation with their attitude toward the menopause and perceived self-efficacy (P < 0.01) But no relationship was found between the quality of life in postmenopausal women and their knowledge of menopausal issues (P > 0.05). The Pearson correlation test showed a statistically significant correlation between the quality of life in postmenopausal women and enabling and reinforcing factors (P < 0.01). Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients between the score of quality of life and the score of factors in Behavioral Analysis Phase of PRECEDE model section.

Table 1.

Profile of demographic variables of the postmenopausal women studied (N=200)

Table 2.

Mean scores of quality of life and behavioral analysis phase of PRECEDE model factors

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between the scores of quality of life in postmenopausal women and behavioral analysis phase of PRECEDE model factors

Regarding the relationship between the quality of life and some demographic variables, the Pearson correlation test showed a statistical inverse correlation of the quality of life in postmenopausal women with their age (P < 0.01 and r = −0.220). Independent t-test results showed that the quality of life in postmenopausal women varied according to their marital and occupational status (P < 0.01). Finally, Spearman correlation test showed that the quality of life in postmenopausal women had significant statistical correlation with their educational level (P < 0.01 and r = 0.287).

DISCUSSION

Based on PRECEDE model, potential factors affecting health problems are classified in three categories of predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors.

In this study, predisposing factors include knowledge, attitude, and perceived self-efficacy. Results of this study showed that the quality of life in postmenopausal women is not related to their knowledge of menopausal issues, which is inconsistent with other study results.[7,21,22,23,24] In fact, the results of other studies in Iran and other countries indicate that the quality of life in postmenopausal women improves following their increased awareness. What is certain is that efforts to increase women's knowledge of self-care can help improvement of the quality of life during menopause. Hunter believes that increasing awareness of women regarding menopause issues improves their attitude toward it, their health behavior, and habits, eventually leading to improvement in the quality of life.[25] The present study observed a significant relationship between the quality of life in postmenopausal women and their attitude toward menopause. In other words, women who had a positive attitude toward menopause had better quality of life. Results of other studies in this field confirm our results. Several studies indicate that the negative attitude of women as well as the society toward menopause affects the frequency and intensity of menopausal symptoms’ experience and that women with negative attitudes experience these symptoms with more severity.[26,27,28,29,30,31,32] On the other hand, the more severe menopausal symptoms experienced, the more negative impact they have on the quality of life in postmenopausal women.[33,34,35,36] Results of these studies show that women with negative attitudes toward menopause suffered more from depression[35] and also that physical symptoms of menopause occur with greater intensity in them.[33,34] Conversely, women with positive attitudes were less depressed and reported less physical symptoms.[33,34] Investigating the relationship between the quality of life in postmenopausal women and their perceived self-efficacy, our results showed that quality of life in postmenopausal women is related to their perceived self-efficacy and improves with its increase. Our findings are consistent with the results of other studies on the effects of perceived self-efficacy on the quality of life and increasing health behaviors.[14,24,37,38,39,40,41] Gerber and Mishra believe that postmenopausal women's confidence in their ability to treat menopausal symptoms is an important factor affecting their quality of life.[14,41] Other studies have also shown that the adaptability of individuals, which is mostly related to their self-efficacy, is an important factor in better mental health and lesser depression of postmenopausal women.[39,40]

In this study, significant correlation was found between the quality of life in women and enabling factors. Our findings showed that women who had greater access to enabling factors also had a better quality of life. One of the enabling factors in this study was access to information resources and participation in educational programs on the issues of menopause. In the field of educational programs as an important enabling factor in improving the quality of life in postmenopausal women, various studies show that participation in such programs, in addition to increasing the awareness of women, improves their attitude, and they feel more confident, powerful, and valuable. Therefore, they feel menopausal symptoms with less intensity and their quality of life improves.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,42] The training classes on menopausal issues, through making a protectionist environment, increases women's sense of responsibility toward their own welfare and, in this way, affect their quality of life.[34] In this study, access to financial resources was another enabling factor, and about 40% of women reported lack of access to financial resources as a reason for not using health services. Various studies show that one of the most important factors in health care utilization by individuals is adequate income and access to financial resources.[43,44] In postmenopausal women, access to financial resources is also one of the factors affecting their quality of life.[45,46,47,48,49,50] According to some studies, women who had greater access to financial resources and a higher income than other women were suffering lesser physical and psychological-social symptoms.[45] Meanwhile, some researchers argue that satisfaction with financial situation is effective even on sexual satisfaction in postmenopausal women and improves the quality of life, especially in the sexual aspect.[41] Another enabling factor that affected the quality of life of postmenopausal women in this study was their daily problems, which had a hindering effect on women's attention to their health-related issues. More than 55% of the subjects stated that their daily problems prevented them from dealing with specific issues of postmenopausal period. Based on the results of other studies, daily problems are one of the factors that have negative effects on the mental health in postmenopausal women and reduce their quality of life.[48] These studies have shown that daily problems, more than hormonal changes, jeopardize the mental health of postmenopausal women and severely affect their quality of life.

Our results showed a significant correlation between the quality of life and reinforcing factors. In this study, reinforcing factors generally include social support perceived by women. Reviewing resources indicate that perceived social support is one of the factors influencing the quality of life in postmenopausal women.[15,49,50,51,52] In this regard, Vagnon states that lack of sufficient understanding of postmenopausal women by their relatives, in many cases, leads these women to visit the clinic.[50] In fact, understanding the menopausal symptoms and the problems in postmenopausal women and support by relatives, especially the spouses who have more interactive relationship with them, can have positive effects on mental conditions’ improvement in postmenopausal women. In this regard, some studies have shown that establishing social support networks and physical and mental health promotion programs helps to improve the quality of life in postmenopausal women greatly.[49] Also, some studies indicate that in the cultures where the status of women after menopause raises in their family and community, and social support from the family members, especially the spouse, increases, the women face less mental disorders and have a better quality of life.[15]

Our results show that some demographic factors such as age, marital status, employment status, and education levels are also the factors affecting the quality of life in postmenopausal women. In this study, younger women had a better quality of life than older women. The results of most studies in this field confirm our results.[12,13,14,53] As shown in these studies, the quality of life of women in the physical, mental, and personal life domains decreases with increase of age,[12,13,14] although in one study, older postmenopausal women reported higher quality of life and lesser psychological symptoms than younger postmenopausal women.[54] Our results indicate that married women had a better quality of life than widows. Other studies have declared marital status also as a factor affecting the quality of life in postmenopausal women. These studies showed that married women had more positive attitudes than divorced women and enjoyed a better quality of life.[36,48,53] The educational level also was a factor affecting the quality of life in postmenopausal women. Most other studies have confirmed this relationship.[11,13,15,36,45,48,53] Based on these studies, the lower the educational level of postmenopausal women, the higher the risk of mental disorders is, and as a result, their mental health decreases.[13] Meanwhile, women who have lower educational levels experienced menopausal symptoms like hot flashes more severely and with greater frequency. Also, they suffered more vaginal dryness and sexual dysfunctions.[45] Confirming these results, Dennerstein stressed that vaginal dryness and sexual dysfunction is reported less by women who have higher educational levels.[48] However, some studies did not approve the relationship between the quality of life and education.[14,10] What is certain is that women who have higher education have greater access to information resources; so, they have higher knowledge and experience fewer symptoms[35,34] and, therefore, will have better quality of life. In other words, higher education usually results in higher incomes and more opportunities in career and social life. In fact, these women had greater access to health services, had more knowledge, and benefited from more medical counseling.[8] The next factor having a significant correlation with quality of life in this study was employment status. Our results showed that retired women had a better quality of life than housewives. Most studies also confirm this issue.[11,13,45] However, in some studies, the relationship between the quality of life of postmenopausal women and their employment status was not confirmed.[10,55] It seems that having a responsibility in an organization increases the confidence in middle-aged women and helps to improve their quality of life.

This study suffers from some limitations. This study was a cross-sectional one which had rather similar and homogenous samples, and the sample size was relatively small. Additionally, we used self-reporting tools.

CONCLUSION

Based on the present study, attitude, perceived self-efficacy, perceived social support, and enabling factors are associated with quality of life in postmenopausal women. So, attention to these issues is essential to women's health planning. Indeed, due to various personal and social factors associated with the quality of life in postmenopausal women, what seems important to enhance their quality of life is an integrated view of their health problems. In fact, it is very difficult to influence the factors such as financial situation, daily problems, educational level, and other personal factors affecting the quality of life in postmenopausal women. Since most women have appropriate access to care centers, it seems that the best and most accessible ways to enhance their quality of life are attention of health service providers to the problems associated with menopause and holding training and consulting classes about menopausal problems, with a health promotion approach. In these classes, in addition to increasing women's knowledge, positive attitude toward menopause and their empowerment to attend their health issues on time should be taken into account. On the other hand, given the influential role of social support in improving the quality of life in postmenopausal women, attracting the participation of other family members, especially spouses, in their physical and mental health promotion programs and also establishing social support networks to provide appropriate emotional and instrumental support for postmenopausal women will definitely help to improve their quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Deputy of Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support for this study. They also thank all the women who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Pesteei Kh, Allame M, Amirkhany M, Motlagh ME. Tehran: Pooneh; 2008. Clinical guide and executive health program team to provide menopausal services to women 60-45 years; pp. 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, Nygaard IE. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology; pp. 1063–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Lin SQ, Wei Y, Gao HL, Wu ZL. Menopause specific quality of life satisfaction in community dwelling menopausal women in china. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23:166–72. doi: 10.1080/09513590701228034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallahzade H, Dehghani Tafti A, Dehghani Tafti M, Hoseini F, Hoseini H. Factors Affecting Quality of Life after Menopause in Women, Yazd 2008. J Shaheed Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2011:552–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcia A. Assessment of quality of life outcome. 1996:71–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL) Qual Life Res. 1993;2:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forouhari S, Rad MS, Moattari M, Mohit M, Ghaem H. The effect of education on quality of life in menopausal women referring to Shiraz Motahhari clinic in 2004. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2009;16:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abedzadeh M, Taebi MM, Saberi F, Sadat Z. Quality of life and related factors in Menopausal women in Kashan city. Iran South Med J. 2009;12:81–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shohani M, Rasouli F, Hagi amiri P, Mahmoudi M. The survey of physical and mental problems of menopause women referred to Ilam health care centers. Iran J Nurs Res. 2007;2:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golyan Tehrani Sh, Mir Mohammad Ali M, Mahmoudi M, Khaledian Z. Study of quality of life and its patterns in different stage of menopause for women in tehran. J Hayat. 2005;8:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RE, Levine KB, Kaliliani L, Lewis J, Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chedraui P, Blumel JE, Belzares E, Bencosme A, Calle A, Baron G, et al. Impaired quality of life among middle aged women: A multicenter Latin American Study. Maturitas. 2008;61:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumel JE, Castelo-Branco C, Binfa L, Gramegna G, Tacla X, Aracena B. Quality of life after the menopause: A population study. Maturitas. 2000;34:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra GD, Brown WJ, Dobson AJ. Physical and mental health: Changes during menopause transition. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:405–12. doi: 10.1023/a:1023421128141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karacam Z, Seker SE. Factors associated with menopausal symptoms and their relationship with the quality of life among Turkish women. Maturitas. 2007;58:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadrian H, Morowati Sharifabad MA, Soleimani Salehabadi H. Paradims of rheumatoid arthritis patients quality of life predictors based on path analysis of the Precede model. J Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2010;14:32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falahi A, Nadrian H, Mohammadi S, Baghiyani Moghadam B. Utilizing the PRECEDE Model to predict quality of life related factors in patients with Ulcer Peptic Disease in Sanandaj, Kurdistan, Iran. Payavard-e-Salamat, The Journal of Allied Medical Sciences School, Medical Sciences/Tehran University. 2009;3:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naderi Z, Zighaymat F, Ebadi A, Kachooee H, Mehdizadeh S. Evaluation of the application of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model on the quality of life of people living with Epilepsy Referring to Baqyatallah Hospital in Tehran. Daneshvar. Sci Res J Shahed Univ. 2009;16:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green LW, Kreuter MW. 4th ed. USA: McGraw-Hill; 2005. Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach; pp. 120–1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karimy M, Niknami SH, Amin Shokravi F, Shamsi M, Hatami A. The Relationship of Breast self-examination with Self-esteem and Perceived Benefits/Barriers of Self-efficacy in Health Volunteers of Zarandieh city. Iran J Breast Dis. 2009;2:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moridi G, Seyedalshohadaee F, Hossainabasi N. The effect of health education on knowledge and quality of life among menopause women. Iran J Nurs. 2006;18:31–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasan Pour Azghadi B, Abbasi Z. Effect of education on middle-aged women's knowledge and attitude towards menopause in Mashhad. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2006;13:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth-Laforce C, Thurston RC, Taylor MR. A pilot study of a Hatha yoga treatment for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. 2007;57:286–95. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elavsky S, Mc Auley E. Physical activity, symptoms, esteem, and life satisfaction during menopause. Maturitas. 2005;52:374–85. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter MS, Liao KL. Problem solving groups for mid-aged women in general practice: A pilot study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1995;13:147–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hess R, Olshansky E, Ness R, Bryce CL, Dillon SB, Kapoor W, et al. Pregnancy and birth history influence women's experience of menopause. Menopause. 2008;15:435–41. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181598301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng MH, Wang SJ, Wang PH, Fuh JL. Attitudes toward menopause among middle-aged women: A community survey in an island of Taiwan. Maturitas. 2005;52:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hess R, Bryce C, Hays Rl. Attitudes towards menopause: Status and race differences and the impact on symptoms. Menopause. 2006;13:986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievert LL, Espinosa-Hernandez G. Attitudes toward menopause in relation to symptom experience in Puebla, Mexico. Women Health. 2003;38:93–106. doi: 10.1300/J013v38n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilbur J, Miller A, Montgomery A. The influence of demographic characteristics, menopausal status, and symptoms on women's attitude toward menopause. Women Health. 1995;23:19–39. doi: 10.1300/J013v23n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huffman SB, Myers JE, Tingle LR, Bond LA. Menopause symptoms and attitudes of African American women: Closing the knowledge gap and expanding opportunities for counseling. J Counsel Dev. 2005;83:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shea JL. Chinese women's symptoms: Relation to menopause, age and related attitudes. Climacteric. 2006;9:30–9. doi: 10.1080/13697130500499914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowles C. Measure of attitude toward menopause using the semantic differential model. Nurs Res. 1986;35:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotem M, Kushnir T, Levine R, Ehrenfeld M. A psycho-educational program for improving women's attitudes and coping with menopause symptoms. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34:233–40. doi: 10.1177/0884217504274417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter M. Coping with menopause: Education and exercise are key interventions. Psychol Today. 2002;35:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avis NE, Assmann SF, Kravitz HM, Ganz MP, Ory M. Quality of life in diverse groups of midlife women: Assessing the influence of menopause, health status and psychosocial and demographic factors. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:933–46. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000025582.91310.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morowatisharifabad M, Nadrian H, Soleimani Salehabadi H, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Asgarshahi M. The Relationship between Predisposing Factors and Self-care Behaviors among Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Fac Nurs Midwifery. 2009;15:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAndrew LM, Napolitano MA, Albrecht A, Farrell NC, Marcus BH, Whiteley JA. When why and for whom there is a relationship between physical activity and menopause symptoms. Maturitas. 2009;64:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saklofske D, Austin E, Galloway J, Davison K. Individual difference correlates of health-related behaviours: Preliminary evidence for links between emotional intelligence and coping. Person Indiv Diff. 2007;42:491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenglass E, Fiksenbaum L, Eaton J. The relationship between coping, social support, functional disability and depression in the elderly. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2006;19:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerber JR, Johnson JV, Bunn JY, O’Brien SL. A longitudinal study of the effects of free testosterone and other psychosocial variables on sexual function during the natural traverse of menopause. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:643–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauld R, Brown RF. Stress, psychological distress, psychosocial factors, menopause symptoms and physical health in women. Maturitas. 2009;62:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Couture MC, Nguyen CT, Alvarado BE, Velasquez LD, Zunzunegui MV. Inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening among urban Mexican women. Prev Med. 2008;47:471–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang WC, Lan TH, Ho WC, Lan TY. Factors affecting the use of health examinations by the elderly in Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:S11–6. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(10)70005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brzyski RG, Medrano MA, Hyatt- Santos JM, Ross JS. Quality of life in low income menopausal women attending primary care clinics. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01852-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nosek M, Kennedy HP, Beyene Y, Taylor D, Gilliss C, Lee K. The effects of perceived stress and attitudes toward menopause and aging on symptoms of menopause. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2010;55:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gur A, Sarac AJ, Nas K, Cevic R. The relationship between educational level and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Guthrie J. The effects of the menopausal transition and biopsychosocial factors on well-being. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002;5:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s007370200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duche L, Ringa V, Melchior M, Varnoux N, Piault S, Zins M, et al. Hot flushes, common symptoms, and social relations among middle-aged no menopausal French women in the GAZEL cohort. Menopause. 2006;13:592–99. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227329.41458.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vagnon A. The experience of the menopause. Review Francais Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1999;80:191–4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Igarashi M, Saito H, Morioka Y, Oiji A, Nadaoka T, Kashiwakura M. Stress vulnerability and climacteric symptoms: Life events, coping behavior and severity of symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;49:170–8. doi: 10.1159/000010241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bresnahan MJ, Murray-Johnson L. The Healing Web. Health Care Women Int. 2002;2:398–407. doi: 10.1080/0739933029008964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Joffe H. Diagnosis and management of mood disorders during the menopausal transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ekstrom H, Hovelius B. Quality of life and hormone therapy in women before and after menopause. Scan J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:115–21. doi: 10.1080/028134300750019025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ehsanpour S, Eivazi M, Davazdah Emami Sh. Quality of life after the menopause and its relation with marital status. IJNMR. 2007;12:130–5. [Google Scholar]