Abstract

Purpose:

Mendelian phenotypes in humans vary from benign variants to lethal disorders. Embryonic lethal phenotypes that are similar to what has been known for a long time in mice have remained largely unknown because of the difficulty in arriving at a molecular diagnosis. The purpose of this study is to test whether next generation sequencing can reveal the underlying etiology of recurrent fetal loss.

Methods:

We hypothesized that exome sequencing combined with autozygome analysis can reveal the underlying mutation in a family in which recurrent fetal loss was likely to be autosomal recessive in origin.

Results:

A novel mutation in CHRNA1 was identified. This gene is known to cause multiple pterygium and fetal akinesia syndrome.

Conclusion:

This is the first report of exome sequencing to identify the cause of recurrent fetal loss and reveal the diagnosis of a lethal human phenotype. Our results should inspire a systematic examination of the extent of “unborn” Mendelian phenotypes in humans using next-generation sequencing.

Keywords: embryonic lethal, exome sequencing, hydrops fetalis, recurrent abortion

Introduction

The recent availability of next-generation sequencing has ushered in a new era of medical genetics and genomics, particularly in the area of Mendelian diseases.1 The pace at which novel disease genes are identified is unprecedented, and patients and families with these diseases are now reaping the benefits from accurate molecular diagnosis.2 The remarkable variability in phenotypic severity observed in these newly “solved” Mendelian disorders raises interesting possibilities about the degree to which the phenotypic spectrum of single-gene mutations can extend. For instance, now it is not only possible to hypothesize the existence of single-gene mutations that are lethal in utero (akin to “embryonic lethal” phenotype in mice) but also to test this hypothesis using next-generation sequencing. In other words, one can now test for the existence of Mendelian disorders that have not yet been cataloged because they are embryonic lethal. In this communication, we show for the first time the use of next-generation sequencing to identify the causative mutation in a family with recurrent fetal loss due to nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF).

Clinical Report

The consultand is a 24-year-old Saudi woman who presented at 15 weeks of gestation for prenatal counseling with her first-cousin husband. She had a history of two fetal losses due to NIHF. The couple has one healthy son, and the family history was negative for malformation syndromes or recurrent fetal loss. Available records on the two pregnancies with NIHF revealed normal karyotype on amniocytes from one and on cord blood from the other. Both pregnancies were terminated therapeutically and parents were counseled for the possibility of an undetermined autosomal recessive cause of the recurrent fetal loss. The current pregnancy developed signs of NIHF at 19 weeks of gestation, but detailed ultrasonographic examination was nonspecific otherwise. Parents were counseled on the possibility of an autosomal recessive disorder and expressed intense interest in pursuing detailed genetic investigation of their current pregnancy. After signing a written informed consent (KFSHRC RAC no. 2080006), cord blood from the fetus was drawn for karyotyping and DNA extraction. High-resolution conventional and molecular karyotype (array comparative genomic hybridization) were both normal.

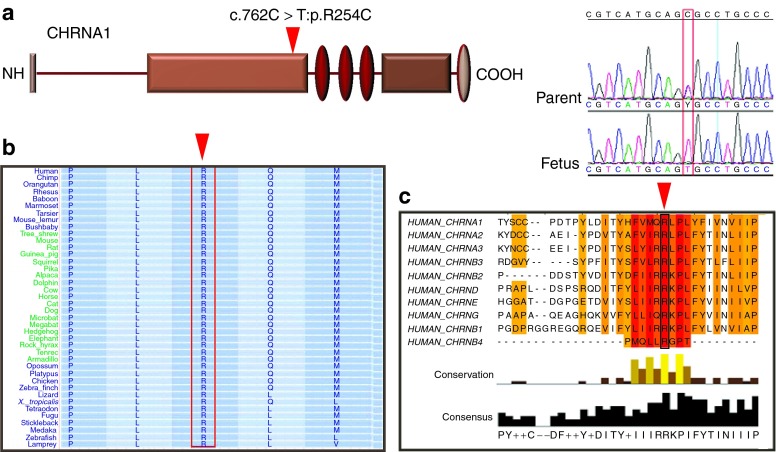

Exome Sequencing and Filtration

We hypothesized that given the consanguineous nature of the parents, the proposed causal autosomal recessive mutation would reside within the autozygome. Because we did not have access to DNA from previously affected pregnancies, we proceeded with exome sequencing of this fetus and filtered the resulting variants by the autozygome. Of 4,400 homozygous coding/splicing variants, 440 resided within the autozygome and of these only 5 were novel, i.e., absent from dbSNP and 200 in-house Saudi exomes (Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S1 online). Of these five missense variants, only two (R254C in CHRNA1 and P825S in SAP130) were absent in 250 Saudi controls by direct sequencing whereas the other three (R634G in ZAK, E25G in MOCS2, and R1168G in KIAA1462) were encountered, albeit at low frequency (Supplementary Table S1 online). The variant c.760C→T, p.R254C in CHRNA1 was particularly interesting because mutations in this gene are known to cause fetal akinesia and NIHF.3 This variant was absent in 178 Saudi controls by direct sequencing and the affected residue was not only conserved across species but was also conserved among all other acetylcholine receptors (Figure 1). In addition, the only other variant that was absent in Saudi controls (P825S in SAP130) is unlikely because mice homozygous for a transposone insertion in this gene lack any discernible phenotype (http://www.jax.org). Therefore, the missense variant in CHRNA1 is the most likely candidate mutation, although we could not confirm segregation due to lack of available tissue from previously affected fetuses.

Figure 1.

Identification of a Mendelian cause of recurrent fetal loss by exome sequencing. (a) Schematic of CHRNA1 protein with the novel mutation indicated by an inverted red triangle. Sequence chromatogram of the fetus and the carrier parent is shown to the right. (b) R254 is strongly conserved in CHRNA1 orthologs. (c) R254 is also conserved across other human CHRN proteins.

Discussion

Next-generation sequencing has quickly proven helpful in a number of clinical settings. Its first application in Mendelian disorders was quickly followed by its adoption by the oncology community, and it is likely that it will be beneficial in common diseases as well (it has already proven effective in Mendelian phenocopies of common diseases).4,5,6 Under the Mendelian category, next-generation sequencing has shown promise in identifying the cause of not only recognized syndromes but also ambiguous clinical presentations.7,8 Next-generation sequencing has been used to diagnose a fetus with hemoglobinopathy based on the knowledge of parental carrier status.9 However, to the best of our knowledge, this technology has not been used to identify the cause of an undiagnosed lethal unborn Mendelian condition. NIHF is the final common pathway of a very heterogeneous group of disorders, and it is often very difficult to discern the underlying etiology due to the nonspecificity of the presentation.10 Mendelian causes of NIHF are numerous, and the case we present shows that next-generation sequencing can be used to effectively identify the cause. We acknowledge that most cases of NIHF are not likely to be Mendelian, but we suggest that next-generation sequencing may be considered in recurrent NIHF or even in the first presentation when no specific cause can be identified. In addition, what this case suggests is that unborn lethal Mendelian conditions are for the first time amenable to genetic analysis at a high resolution. It will be extremely informative to systematically study products of conception for the possible occurrence of lethal Mendelian mutations. An attractive population would be consanguineous healthy couples with a history of recurrent abortion or fetal loss (especially when they have at least one healthy child as this can eliminate a lot of maternal causes of recurrent pregnancy loss) to increase the odds of finding such mutations. Cataloging of these mutations will provide insight into previously untapped Mendelian genes, some of which may already have equivalent embryonic lethal mouse phenotype.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family members for their enthusiastic participation and also the physicians who cared for this family. Hadia Hijazi helped with sequence analysis, and the Genotyping and Sequencing Core Facilities at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center provided technical support.

Supplementary Materials

References

- Gilissen C, Hoischen A, Brunner HG, Veltman JA. Unlocking Mendelian disease using exome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2011;12:228. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CS, Naidoo N, Pawitan Y. Revisiting Mendelian disorders through exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2011;129:351–370. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalk A, Stricker S, Becker J.et al. Acetylcholine receptor pathway mutations explain various fetal akinesia deformation sequence disorders Am J Hum Genet 200882464–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SP, Morin RD, Khattra J.et al. Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution Nature 2009461809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD.et al. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes Nature 2009461272–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mayouf SM, Sunker A, Abdwani R.et al. Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus Nat Genet 2011431186–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W.et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 200910619096–19101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthey EA, Mayer AN, Syverson GD.et al. Making a definitive diagnosis: successful clinical application of whole exome sequencing in a child with intractable inflammatory bowel disease Genet Med 201113255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YM, Chan KC, Sun H.et al. Maternal plasma DNA sequencing reveals the genome-wide genetic and mutational profile of the fetus Sci Transl Med 2010261ra91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini C, Hennekam RC, Bonioli E. A diagnostic flow chart for non-immune hydrops fetalis. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:852–853. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.