Abstract

Metabolism of the hepatotoxicant furan leads to protein adduct formation in the target organ. The initial bioactivation step involves cytochrome P450-catalyzed oxidation of furan, generating cis-2-butene-1,4-dial (BDA). BDA reacts with lysine to form pyrrolin-2-one adducts. Metabolic studies indicate that BDA also reacts with glutathione (GSH) to generate 2-(S-glutathionyl)butanedial (GSH-BDA), which then reacts with lysine to form GSH-BDA-lysine cross-links. To explore the relative reactivity of these two reactive intermediates, cytochrome c was reacted with BDA in the presence and absence of GSH. As judged by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, BDA reacts extensively with cytochrome c to form adducts that add 66 Da to the protein, consistent with the formation of pyrrolinone adducts. Addition of GSH to the reaction mixture reduced the overall extent of adduct formation. The mass of the adducted protein was shifted by 355 Da as expected for GSH-BDA-protein cross-link formation. LC-MS/MS analysis of the tryptic digests of the alkylated protein indicated that the majority of adducts occurred on lysine residues, with BDA reacting less selectively than GSH-BDA. Both types of adducts may contribute to the toxic effects of furan.

Keywords: furan; cytochrome c; cross-linking; α,β-unsaturated dialdehyde; mass spectrometry; GSH; reactive metabolites

INTRODUCTION

Furan is a liver toxicant and carcinogen in rats and mice.1 The mechanism of carcinogenesis is currently unknown, however widespread cell death followed by compensatory cellular proliferation has been implicated as a possibility.2 This could either be through selection of pre-cancerous cells or through mutational events secondary to cell toxicity.2 Protein adduct formation is likely an important step in furan toxicity. Approximately 13% of a dose of radiolabeled furan (8 mg/kg) was covalently bound to rat liver proteins 24 h after treatment.3 Furan is converted to a protein-binding reactive intermediate as a result of cytochrome P450 catalyzed oxidation.3,4 In vitro, the reactive metabolite can be trapped with either semicarbazide or glutathione (GSH) and has been identified as cis-2-butene-1,4-dial (BDA).4–6 Chemical model studies indicate that BDA reacts with lysine residues to form pyrrolin-2-one adducts.7 In addition, it is able to link N-acetylcysteine or GSH to lysine through pyrrole ring formation.7,8 Studies in rat hepatocytes demonstrated that BDA cross-links GSH to a variety of amines, including proteins, in a metabolism-dependent process.8,9 Analysis of furan urinary metabolites indicates that similar chemistry is occurring in vivo; both lysine pyrrolin-2-one and cysteine-BDA-lysine pyrrole cross-links are precursors to the observed metabolites in urine of furan-treated rats.8,10,11

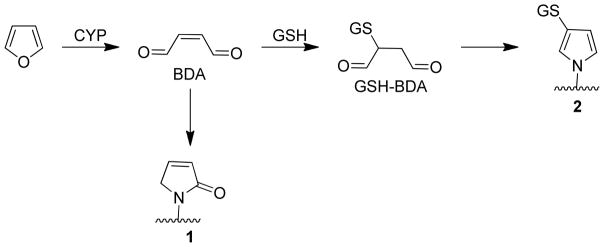

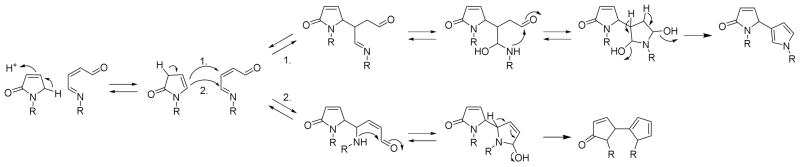

Based on these studies, two protein reactive metabolites are likely generated during furan metabolism, BDA and 2-(S-glutathionyl)butanedial (GSH-BDA, Scheme 1). BDA can react directly with proteins to form pyrrolin-2-one lysine adducts (1). Alternatively, the reaction of BDA with GSH generates GSH-BDA, which is expected to react with protein lysine residues to form GSH-BDA-protein cross-links (2). To explore the relative protein reactivity of these two intermediates, cytochrome c was reacted with BDA in the presence and absence of GSH. This protein lacks free sulfhydryl residues so it is particularly useful model for the investigation of protein adduct formation at nonthiol nucleophilic sites.12,13 The extent of alkylation was determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectral analysis and the location of the modifications was determined by LC-MS/MS analysis of tryptic digests.

Scheme 1.

Proposed pathways of protein adduct formation as a result of furan metabolism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Caution

BDA is toxic and mutagenic in cell systems. It should be handled with proper safety equipment and precautions.

Chemicals

Aqueous solutions of BDA were prepared from 2,5-diacetoxy-2,5-dihydrofuran as previously described.14,15 Optima® grade acetonitrile was purchased from Fisher Chemical (Fair Lawn, NJ). Sequencing grade modified trypsin was obtained from Promega (Fitchburg, WI). ZipTips were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). All other reagents were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Protein Modification Reactions

The reaction conditions were similar to those reported by Zhu et al for the reaction of 4-oxo-2-nonenal (ONE) with proteins in the presence and absence of GSH.16 A two h reaction time was chosen since the reaction of BDA with model protein nucleophiles was complete within this time frame.6,7,9 Horse heart cytochrome c (250 μM) was reacted with BDA (0, 50, 100, or 500 μM) in the presence or absence of 1 mM GSH in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, at 37 °C for 2 h (total volume: 0.25 mL). The reactions were started by the addition of BDA to the mixture. The reaction mixtures were frozen at −20° C until tryptic digestion or MALDI-TOF-MS analysis.

MALDI-TOF-MS analysis

The reaction mixtures (13 μL) were acidified with 0.7 μL of 10% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). A C4 ZipTip was washed with 50% (v/v) aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA and then equilibrated with 0.1% (v/v) TFA solution. The acidified sample (10 μL) was extracted with the prepared ZipTip and washed with 0.1% (v/v) TFA. Finally, the sample was eluted with 75% (v/v) aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA (1.2 μL). The protein sample was mixed on the stainless steel target with an equal volume of a saturated aqueous solution of sinapic acid containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA. MALDI-TOF mass spectra were acquired with a Bruker BiFlex III MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) equipped with a pulsed nitrogen laser (2 ns pulse at 337 nm). This instrument is located in the Center for Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics in the College of Biological Sciences, University of Minnesota. All spectra were collected in the positive ion mode. Spectra were acquired in either linear or reflectron modes. All data were processed with XMass (Bruker Daltonics).

Tryptic Digestion

Modified cytochrome c (77.5 μg) was diluted 1:4 in nanopure water and acetonitrile was added to a final concentration of 10% (v/v) acetonitrile (100 μL). The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.5–9.0 by adding 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 1 mM CaCl2. The lyophilized trypsin was solubilized in 50 mM acetic acid and added to the protein solution to a final concentration of ~1:60 protease:protein (w/w). After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the samples were cooled to room temperature and the pH was adjusted to 3 with glacial acetic acid (1–5 μL). The digested samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis by LC-ESI+-MS/MS.

LC-ESI+-MS/MS

Reverse-phase LC was performed with an Eksigent nanoLC-Ultra 2D LC system (Dublin, CA) equipped with a 10-cm fused silica emitter (75 Mm inner diameter from New Objective, Woburn, MA) in-house packed with reverse-phase Zorbax SB C18 5 Mm resin (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The column was eluted at a constant flow rate of 300 nL/min with the following gradient: 25 min linear gradient from 95% A, 5% B to 80% A, 20% B; 25 min linear gradient to 10% A, 90 % B, 10 min hold at 10% A, 90% B; 5 min linear gradient to 95% A, 5% B, then a 15 min hold at 95% A, 5% B. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water (v/v) and solvent B was acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. ESI+-MS/MS was performed with a Thermo Scientific LTQ-Orbitrap Velos instrument (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) in positive ion mode. This instrument is located in the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota. General mass spectrometric conditions were: electrospray voltage, 1.6 kV; capillary temperature, 275 °C; no sheath or auxiliary gas flow. Protein digests (1 μL) pre-acidified with glacial acetic acid were injected onto the column. MS data were acquired with the Orbitrap analyzer at a resolving power of 60,000 at 400 m/z and the MS2 analysis was performed with ion trap detection. Nine scan events were used as follows: (Event 1) m/z 300–2000 full scan MS and (Events 2–9) data-dependent scan MS/MS on the eight most intense ions from event 1. An isolation window of 2.5 m/z, ion selection threshold of 500 counts, activation q = 0.25, and activation time of 30 ms were applied for MS2 acquisitions. The spectra were recorded using dynamic exclusion of previously analyzed ions for 0.5 min with two repeats and a repeat duration of 0.5 min. Ions with unassigned charge states or charge states of <2 were excluded. The MS/MS normalized collision energy was set to 35%. The lock mass was enabled for accurate mass measurements with polydimethylcyclosiloxane (m/z 445.120024) ions used for internal calibration.

Data Analysis

Tryptic digestion MS data was analyzed using Proteome Discoverer 1.3 and Xcalibur 2.1 (Thermo Scientific). Peak lists and predicted CID fragmentation were generated using Proteome Discoverer, while peak areas and observed fragmentation were examined using the Qual Browser module of Xcalibur. Precursor ions were required to have a mass tolerance of 5 ppm, while fragment ions were required to have a mass tolerance of 0.8 Da. Dynamic modifications were initially searched on lysine residues using Proteome Discoverer; subsequent investigations explored modification of other amino acid residues. The monoisotopic modification masses were: 48.000, 66.011, 84.021, or 355.084 (Scheme 2). The peptide window for the peak list was set for 300–6000 Da (singly-charged equivalent). The search database consisted of the most recent sequence for horse heart cytochrome c (Equus caballus, NCBI accession: 1FI7_A, version GI: 159162308). Xcorr scores and mass deviations were used as significance cut-offs. All peptides assigned a “high” confidence indicator by Proteome Discoverer were investigated further. Once a peptide was identified, its existence in the samples was confirmed by examination of the accurate mass (5 ppm) extracted ion chromatogram from the full scan data using Qual Browser. Inclusion in Tables 1 and 2 required that the peptide was detectable in all experimental replicates but not in the controls. In addition, the collision induced mass spectrum was required to be consistent with the predicted fragmentation of the modified peptide. All spectra obtained for the modified peptides are displayed in the Supporting Information.

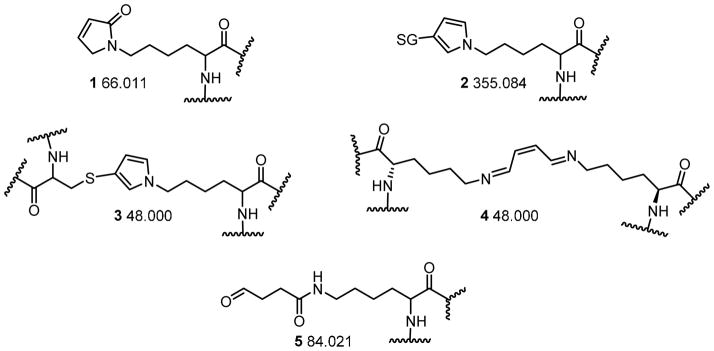

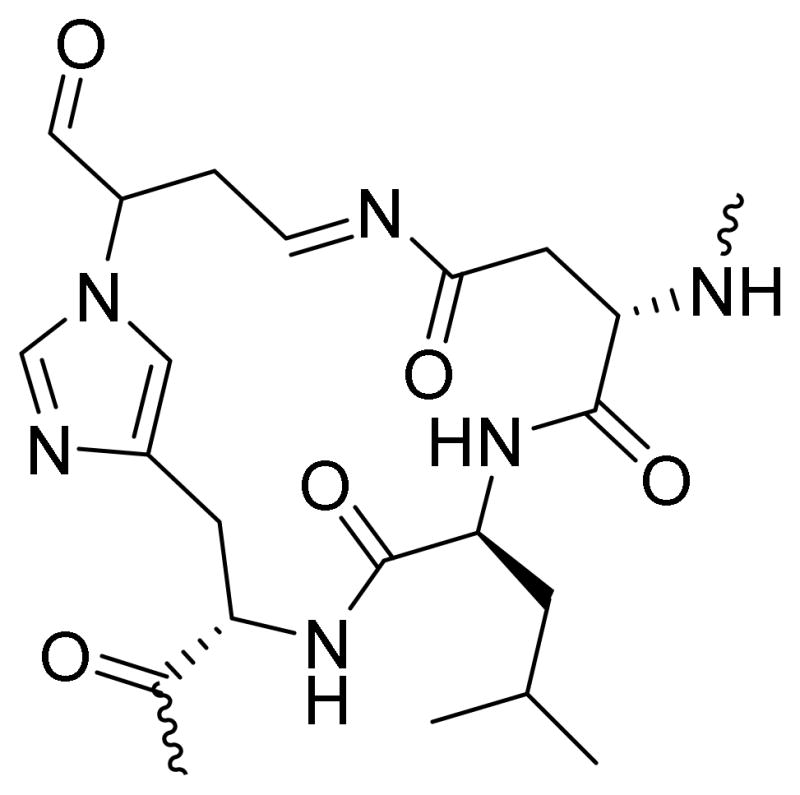

Scheme 2.

Proposed structures of protein modifications and the monoisotopic mass shift corresponding to each.

Table 1.

Cytochrome c peptides modified with BDA.

| Peptide Sequence1 | Position | Residue | Modification | Theoretical Mass | Avg. Observed Mass | μM BDA | 50 | 100 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM GSH | - | - | - | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | ||||||

| Modified peptide detected | ||||||||||||

| GkkIFVQK | 6–13 | K7 & K8 | +66 x 2 | 1079.625 | 1079.624 | X | X | X | X | |||

| kIFVQK | 8–13 | K8 | +66 | 828.498 | 828.498 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| HkTGPNLHGLFGR | 26–38 | K27 | +66 | 1499.787 | 1499.786 | X | X | X | X | |||

| TGPNLhGLFGR | 28–38 | H33 | +66 | 1234.633 | 1234.632 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| kTGQAPGFTYTDANK2 | 39–53 | K39 | +66 | 1664.792 | 1664.792 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| kTGQAPGFTYTDANkNK | 39–55 | K39 & K53 | +66 x 2 | 1972.940 | 1972.941 | X | ||||||

| TGqAPGFTYTDANK | 40–53 | Q42 | +66 | 1536.697 | 1536.696 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TGQAPGFTYTDANkNK | 40–55 | K53 | +66 | 1778.834 | 1778.835 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TGQAPGFTYTDANkNK | 40–55 | K53 | +84 | 1796.845 | 1796.844 | X | X | X | X | |||

| NkGITWK | 54–60 | K55 | +66 | 912.494 | 912.493 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| GITWkEETLMEYLENPK | 56–72 | K60 | +66 | 2147.037 | 2147.038 | X | ||||||

| EETLMEYLENPkK | 61–73 | K72 | +66 | 1689.804 | 1689.805 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| kYIPGTK | 73–79 | K73 | +66 | 872.488 | 872.488 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MIFAGIkK3 | 80–87 | K86 | +66 | 973.554 | 973.553 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MIFAGIkkK | 80–88 | K86 & K87 | +66 x 2 | 1167.660 | 1167.659 | X | X | |||||

| MIFAGIkkK | 80–88 | K86 & K87 | +66,+484 | 1149.649 | 1149.649 | X | X | X | ||||

| kTEREDLIAYLK | 88–99 | K88 | +66 | 1544.832 | 1544.832 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TEREDLIALkK | 89–100 | K99 | +66 | 1544.832 | 1544.833 | X | X | X | ||||

| EDLIAYLkK | 92–100 | K99 | +66 | 1158.640 | 1158.641 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

Lower case letter indicates site of adduction; mass spectra of each peptide is displayed in the Supporting Information.

Detected small amount of +84 at Lys39 in this peptide

Some samples had MIFAGIk

Proposed cross-link where two BDA-derived adducts have condensed.

Table 2.

Cytochrome c peptides modified with GSH-BDA

| Peptide Sequence1 | Position | Residue | Theoretical Mass | Avg. Observed Mass | μM BDA: | 50 | 100 | 500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM GSH: | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | |||||

| Modified peptide detected | ||||||||

| kIFVQK | 8–13 | K8 | 1117.571 | 1117.572 | X | X | X | |

| HkTGPNLHGLFGR | 26–38 | K27 | 1788.860 | 1788.861 | X | X | X | |

| kTGQAPGFTYTDANK | 39–53 | K39 | 1953.865 | 1953.865 | X | X | X | |

| TGQAPGFTYTDANkNK1 | 40–55 | K53 or K55 | 2067.908 | 2067.907 | X | X | X | |

| NkGITWK | 54–60 | K55 | 1201.568 | 1201.567 | X | X | X | |

| EETLMEYLENPkK | 61–73 | K72 | 1978.877 | 1978.880 | X | |||

| kYIPGTK | 73–79 | K73 | 1161.561 | 1161.562 | X | X | X | |

| YIPGTkMIFAGIK | 74–86 | K79 | 1793.897 | 1793.898 | X | X | X | |

| MIFAGIkK | 80–87 | K86 | 1262.627 | 1262.6278 | X | X | X | |

| kTEREDLIAYLK | 88–99 | K88 | 1833.905 | 1833.9068 | X | X | X | |

Lower case letter indicates site of adduction; mass spectra of each peptide is displayed in the Supporting Information.

Cannot distinguish between adduction at K53 and K55.

RESULTS

Overview

To determine the extent of cytochrome c modification by BDA or GSH-BDA, the protein was incubated with 0–500 MM BDA in the presence or absence of 1 mM GSH. Two different, complementary techniques were used to detect protein modification in these reactions. MALDI-TOF was employed to measure overall extent of modification, establishing the number of modifications per protein along with the mass of each modification. The locations of the modifications were determined through high resolution LC-MS/MS analysis of tryptic digests.

Five different protein adduct structures were proposed for BDA-derived adducts (Scheme 2). The pyrrolin-2-one adduct, 1, was expected to be the major BDA-derived lysine adduct based on model studies with Nα-acetyl lysine.7 This adduct would add 66.011 Da to the mass of the protein or a peptide. When GSH was included in the reaction, the GSH-BDA-lysine cross-link 2 was expected to be the major product;8 this modification would raise the protein/peptide mass by 355.084 Da. Several other possible adducts were also considered. The cysteine-BDA-lysine pyrrole cross-link 3 would add 48.000 Da to the protein’s mass. However, this adduct was unlikely since the only two cysteine residues in cytochrome c are associated with the heme group. Lysine-BDA-lysine cross-links would also increase the protein’s mass by 48 Da with the expected structure a double-Schiff base cross-link (4, Scheme 2) since lysinyl amines preferentially react via 1,2-addition with the aldehydic carbon.7 Finally, since other alkenediones react with lysine residues to form 4-ketoamide adducts,17 we considered the possible formation of a similar BDA derived product, 4-ketoamide adduct 5 (Scheme 2). This adduct would increase the protein or peptide’s mass by 84.021 Da.

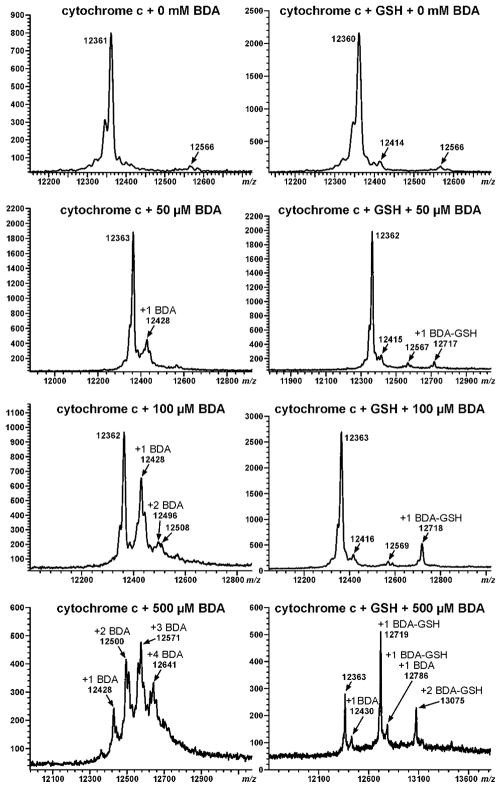

MALDI-TOF analysis

MALDI-TOF analysis of the reaction mixtures indicated that reaction of cytochrome c with BDA increased the protein’s mass by 66 Da (Figure 1); this increase is consistent with the formation of pyrrolinone adducts 1 (Scheme 2). In addition, there were small peaks on either side of the 12,428 Da signal (cytochrome c plus 66 Da), indicating that other modifications were formed in lower amounts. These signals are consistent with the addition of 48 or 84 Da to the protein. The number of modifications per protein increased with higher BDA concentration. When BDA was in excess, there is no appreciable amount of unreacted protein detected in the reaction mixture with as many as four modifications per protein clearly seen.

Figure 1.

MALDI-TOF analysis of 0.25 mM cytochrome c following reaction with 0–0.5 mM BDA in the presence or absence of 1 mM GSH.

Addition of GSH to the reaction mixtures reduced the overall extent of adduct formation (Figure 1). The inclusion of GSH also altered the mass of the alkylated protein; it increased by 355 Da. This mass shift is consistent with the formation of GSH-BDA-lysine pyrrole cross-links (adduct 2, Scheme 2). The presence of GSH reduced but did not eliminate the formation of BDA-derived adducts since both GSH-BDA- and BDA-adducted proteins were observed at the highest concentration of BDA. The levels of GSH-BDA-modified protein were much greater than those of the BDA-modified protein in the GSH-containing reaction mixtures, suggesting that the reaction of BDA with GSH to form GSH-BDA was more rapid than the direct alkylation of protein nucleophiles by BDA.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Tryptic Digests

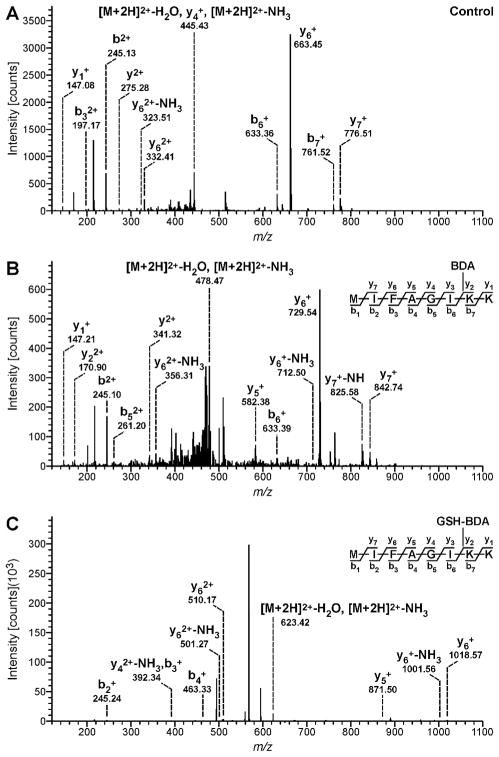

Adduct location was determined by analyzing tryptic digests of the reaction mixtures by LC-MS/MS on a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer. Proteome Discoverer software was employed to identify the alkylated peptides. Lists of the BDA- and GSH-BDA-modified peptides are displayed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Representative collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra obtained for a peptide modified with either BDA or GSH-BDA are shown in Figure 2. The CID spectra for all the identified peptides are presented in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Example MS/MS spectra generated by Proteome Discoverer for the MIFAGIKK peptide from 0.25 mM cytochrome c reated with 0.1 mM BDA in the presence or absence of 1 mM GSH. A: Peptide from control reaction; B: Peptide from the reaction with cytochrome c and BDA; C: Peptide from reaction with cytochrome c, BDA and GSH.

When cytochrome c was reacted with BDA alone, the most common peptide modification resulted from the addition of 66 Da to lysine residues (Table 1). This mass shift and amino acid modification is consistent with the formation of BDA-derived pyrrolinone adduct 1. This BDA-derived modification of Lys7, Lys8, Lys27, Lys39, Lys53, Lys55, Lys72, Lys73, Lys86, Lys88 or Lys 99 was detected at all BDA concentrations (Table 1). Lys87 was alkylated at 100 and 500 μM BDA but this adduct was only observed in peptides that also contained a BDA-derived modification on Lys86. Alkylation of Lys60 by BDA was detected only at the highest BDA concentration.

Several peptides with two +66 Da BDA-lysine modifications were also observed. In addition to the peptide containing adducts on Lys86-Lys87 (MIFAGIkkK), double pyrrolinone adducts were observed on Lys7-Lys8 (GkkIFVQK), and Lys39-Lys53 (kTGQAPGFTYTDANkNK). The double +66 modifications of Lys7 and Lys8 were observed at all concentrations whereas the double +66 modifications of Lys39 and Lys53 and Lys86-Lys87 were only detected at 500 μM BDA. Another double adduct on peptide MIFAGIKKK was observed at 100 and 500 μM BDA; the mass of this peptide was increased by 114 Da with the addition of 66 Da and 48 Da associated with Lys86 and Lys87, respectively. One possible explanation for these observations is that there is a pyrrolinone adduct on Lys 86 and Lys 87 is involved with a double Schiff base cross-link with Lys88 (adduct 4). However, the CID spectrum of this modified peptide (Supporting Information, p. S19) did not exhibit b7+ and y2+ ions expected for this proposed double adduct. The addition of 114 Da to the mass of the b8 and y3 ions of this peptide indicates that these modifications may be linked to each other. Therefore, we hypothesize that this modified peptide resulted from the condensation of two adjacent BDA adducts as proposed in Scheme 3. Additional studies will be required for further structural characterization of this minor adduct.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanisms of condensation of two adjacent BDA-lysine adducts where R represents two adjacent lysine residues.

A search for +66 Da modifications at all nucleophilic amino acids indicated that BDA also reacted with His33 and Gln42 to form +66 adducts (Table 1). These modified peptides were observed at all BDA concentrations. The adduct to glutamine is likely a pyrrolinone adduct to the amide nitrogen since this amide nitrogen has shown weak reactivity to aldehydes in previous studies.8 The structure of the His33 adduct likely results from initial 1,4-addition of the imidazole nitrogen of histidine to BDA as observed with other α,β-unsaturated aldehydes.18–20 Since this reaction would increase the mass of the peptide by 84 Da and an increase in 66 Da was observed, it is likely that the initial adduct underwent further reaction with another amino acid residue in this peptide. An examination of the modified peptide, TGPNLHGLFGR, indicated that there was an asparagine residue at position 31 that could react with a histidine adduct at position 33. Condensation with the asparagine’s amide nitrogen with the histidine adduct’s free aldehyde group would yield a modified protein shifted by 66 Da (Scheme 4). Consistent with the proposed structure, this adduct was unstable to fragmentation; while the b6-b10 ions were all increased in mass by 66 Da, the y7-y9 ions were lacking this modification (Supporting Information, p. S6). The loss of 66 Da was not observed in any of the spectra of peptides where the BDA modification was on a lysine residue. An enamine histidine adduct has been proposed as the reaction product of trans,trans-2,4-decadienal (DDE) with this histidine residue.21 This adduct results from initial 1,2-addition to the aldehyde followed by rearrangement to the enamine. This type of modification is not possible with BDA.

Scheme 4.

Proposed structure of the histidine-asparagine cross-link.

Only one peptide, TGQAPGFTYTDANKNK, had significant amounts of +84 Da modification (Table 1); this adduct was located on Lys53, indicating that ketamide adducts (5) are possible but not very abundant. A similar modification was observed at Lys39 but the levels of this adducted peptide were very low and not present in all replicates (data not shown).

The inclusion of GSH in the reaction mixture affected the types of BDA-derived adducts formed as well as their location. Peptides containing Lys8, Lys27, Lys39, Lys55, Lys73, Lys79, Lys86, or Lys88 increased by +355 Da at all BDA concentrations; a peptide containing Lys72 was similarly modified at the highest BDA concentration (Table 2). The CID spectra indicated that the location of these adducts was on the identified lysine residue. These data support the formation of GSH-BDA-lysine cross-links at these sites. We could not distinguish between adduction at Lys53 or Lys55 for peptide TGQAPGFTYTDANKNK since the fragment ions for that portion of the peptide were difficult to detect.

The presence of GSH reduced but did not eliminate the formation of BDA-derived peptides. Peptides containing +66 adducts at His33, Lys39, Gln42, Lys53, Lys55, Lys72, Lys73, Lys86, Lys88 and Lys99 were detected at all three BDA concentrations. Peptides containing the +66 adduct at Lys8 were detected in the reaction mixtures containing 100 or 500 μM BDA and 1 mM GSH. The +84 modification of Lys53 was only detected at the highest BDA concentration with GSH whereas it had been observed at all BDA concentrations in the absence of GSH. Similarly, there was a marked reduction in the detection of doubly modified +66 peptides upon inclusion of GSH. Under these reaction conditions, they were detected only in the reactions performed with 500 μM BDA.

DISCUSSION

The MALDI-TOF results show that BDA is very reactive with protein nucleophiles (Figure 1). The inclusion of GSH in the reaction mixtures affected protein alkylation in several ways. First, it reduced the overall extent of protein alkylation by BDA, decreasing the direct modification of cytochrome c by BDA. This reduction in protein adducts indicates that GSH effectively competed with cytochrome c for reaction with BDA. Second, reaction of GSH with BDA generated a reactive intermediate, GSH-BDA, which was also capable of alkylating protein nucleophiles. The reduced protein alkylation by GSH-BDA relative to BDA (Figure 1) suggests that GSH-BDA may be less reactive than BDA. However, fewer GSH-BDA-derived protein adducts were formed in part because the glutamyl α-amino group of the same or different GSH molecule will compete with protein nucleophiles for reaction with GSH-BDA to form either intra- or intermolecular GSH-BDA-GSH cross-links.6,7 Protein modification by GSH-BDA still occurred because the ε-amino group of lysine is more nucleophilic than the glutamyl α-amino group of GSH. 8,9

LC-MS/MS analysis of the tryptic digests of the alkylated proteins indicated that both BDA and GSH-BDA primarily targeted protein lysine residues; BDA reacted with lysine to form predominantly adduct 1 and GSH-BDA alkylated lysine residues via a Paal-Knorr condensation to form adducts with structure 2. BDA also modified histidine and glutamine residues. Both BDA- and GSH-BDA-derived protein adducts are formed as a result of initial 1,2-addition of lysine to the carbonyl carbon of the intermediates’ aldehyde moiety. This is similar to what has been reported for other compounds containing an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), ONE, DDE and 9,12-dioxo-10(E)-dodecenoic acid (DODE).13,16,22–24 These compounds reacted more selectively with cytochrome c than BDA or GSH-BDA, forming stable adducts at fewer sites. This selectivity is likely a result of the reversibility of the initial 1,2-addition product formed.24 Consistent with this proposal, many more modified lysine residues were observed when HNE adducts were stabilized by reaction with sodium borohydride.13

The stable adducts formed from DODE and ONE resulted from rearrangement of the initially formed Schiff base to the more stable ketoamide adducts.16,23 This rearrangement is a minor event for BDA as evidenced by the detection of a +84 adduct on Lys53 and, possibly Lys39 of cytochrome c (Table 1). It is not clear why the ketoamide adducts only occurred at these positions. It is likely that the local protein structure allows for the rearrangement of the Schiff base to a ketoamide adduct at this site. Model studies with Nα-acetyl lysine indicate that the formation of the pyrrolinone adduct is preferred.7

The formation of irreversible GSH-protein adducts is not unique to BDA. ONE is capable of cross-linking GSH to proteins in vitro.16 In contrast to our observations with BDA where GSH reduced BDA-derived protein adducts, GSH enhanced protein alkylation of model proteins by ONE, where the dominant protein adducts were GSH-ONE-protein cross-links. This increase in protein alkylation in the presence of GSH was explained by the difference in reactivity of ONE and GSH-ONE. Irreversible modification of lysine residues by ONE is slow whereas the resultant GSH-ONE reaction product, a substituted 4-ketoaldehyde, reacts rapidly with lysine groups to form irreversible cross-links.16 In contrast to the slow formation of stable ONE-derived ketoamide adducts,17 the irreversible formation of BDA-lysine pyrrolinone adducts is relatively fast,7 resulting in more extensive protein alkylation in the absence of GSH.

GSH-BDA reacted with cytochrome c with more selectivity than BDA as evidenced by the observation that BDA alkylated more amino acid residues than GSH-BDA (Tables 1 and 2). There was significant overlap is the lysine residues modified by these two reactive intermediates; they both reacted with Lys8, Lys27, Lys39, Lys 53, Lys55, Lys 72, Lys 73, Lys86 and Lys 88. BDA also alkylated Lys7, Lys60, Lys87 and Lys99 as well as His33 and Gln42. GSH-BDA but not BDA adducts were detected on Lys79. HNE, DDE, DODE and ONE reacted with many of the same lysine residues in cytochrome c.13,21–23 Hot spots of alkylation by all these α, β-unsaturated aldehydes include Lys5-Lys8, Lys86-Lys88 and Lys99. Interestingly, the adduct distribution of BDA is very similar to that reported for the distribution of unstable adducts of HNE, including adducts at His33.13,22 DDE also reacted with this histidine residue.21 The steric and electronic effects of the substituents on the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety will exert control over the compound’s reactivity with specific lysine residues. Site selectivity will also be determined by the residue’s susceptibility to modification. Nucleophilicity varies between lysines in a protein and is influenced by the local microenvironment created by protein tertiary structure.25

Further studies are required to determine the role these protein modifications play in the overall toxic effects of furan. Proteomic studies with [14C]furan indicates that the reactive metabolite(s) of furan targets lysine rich proteins.26 Our studies demonstrate that these adducts could be either BDA-lysine or GSH-BDA-lysine adducts. Immunoblot analysis of liver proteins with anti-GSH antibodies provides evidence for the formation of GSH-BDA-protein cross-links in furan exposed liver.8 Degradation products of these two lysine adducts are detected in the urine of furan-treated rats, indicating that both types of adducts are formed in vivo.8,10,11 The balance of these two adducts will depend on the GSH concentration in the cell.

In summary, we have demonstrated that both BDA and GSH-BDA alkylate protein lysine residues, with BDA being the more reactive of the two compounds. Since the two products are very different in chemical structure, it is likely that they impact protein structure and function in diverse ways. Future studies will explore how these two pathways contribute to the overall toxicity and carcinogenicity of furan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

This research was funded by ES-10577 from the National Institutes of Health. M.P. was funded by a fellowship from the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Minnesota. The Analytical Biochemical Shared Resource at the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota is funded by National Cancer Institute Center Grant CA-77598. Funds for the purchase of the LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer were provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-RR-024618. The MALDI-TOF instrument is located in the Center for Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics in the College of Biological Science at the University of Minnesota. This work was carried out in part using hardware and software provided by the University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute.

We thank Thomas Krick for his assistance with the Bruker BioFlex III mass spectrometer. We thank Jingjing Shen for her assistance with cytochrome c reaction and tryptic digestion.

Abbreviations

- BDA

cis-2-butene-1,4-dial

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- DDE

trans,trans-2,4-decadienal

- DODE

9,12-dioxo-10(E)-dodecenoic acid

- GSH

glutathione

- GSH-BDA

2-(S-glutathionyl)butanedial

- HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- LC-ESI+-MS/MS

high performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization (positive mode) tandem mass spectrometry

- MALDI-TOF-MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- ONE

4-oxo-2-nonenal

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

Supporting Information includes CID spectra for the peptides reported in Tables 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.National Toxicology Program. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of furan in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice vol. NTP Technical Report No. 402. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; Research Triangle Park, NC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson DM, Goldsworthy TL, Popp JA, Butterworth BE. Evaluation of genotoxicity, pathological lesions, and cell proliferation in livers of rats and mice treated with furan. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1992;19:209–222. doi: 10.1002/em.2850190305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burka LT, Washburn KD, Irwin RD. Disposition of [14C]furan in the male F344 rat. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1991;34:245–257. doi: 10.1080/15287399109531564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar D, Burka LT. Studies on the interaction of furan with hepatic cytochrome P-450. J Biochem Toxicol. 1993;8:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jbt.2570080103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LJ, Hecht SS, Peterson LA. Identification of cis-2-butene-1,4- dial as a microsomal metabolite of furan. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:903–906. doi: 10.1021/tx00049a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson LA, Cummings ME, Vu CC, Matter BA. Glutathione trapping to measure microsomal oxidation of furan to cis-2-butene-1,4-dial. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1453–1458. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.004432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen LJ, Hecht SS, Peterson LA. Characterization of amino acid and glutathione adducts of cis-2-butene-1,4-dial, a reactive metabolite of furan. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:866–874. doi: 10.1021/tx9700174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu D, Sullivan MM, Phillips MB, Peterson LA. Degraded protein adducts of cis-2-butene-1,4-dial are urinary and hepatocyte metabolites of furan. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:997–1007. doi: 10.1021/tx800377v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson LA, Phillips MB, Lu D, Sullivan MM. Polyamines are traps for reactive intermediates in furan metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1924–1936. doi: 10.1021/tx200273z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellert M, Wagner S, Lutz U, Lutz WK. Biomarkers of furan exposure by metabolic profiling of rat urine with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and principal component analysis. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:761–768. doi: 10.1021/tx7004212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu D, Peterson LA. Identification of furan metabolites derived from cysteine-cis-2-butene-1,4-dial-lysine cross-links. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:142–151. doi: 10.1021/tx9003215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Person MD, Mason DE, Liebler DC, Monks TJ, Lau SS. Alkylation of cytochrome c by (glutathion-S-yl)-1,4-benzoquinone and iodoacetamide demonstrates compound-dependent site specificity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:41–50. doi: 10.1021/tx049873n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang X, Sayre LM, Tochtrop GP. A mass spectrometric analysis of 4- hydroxy-2-(E)-nonenal modification of cytochrome c. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46:290–297. doi: 10.1002/jms.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrns MC, Vu CC, Peterson LA. The formation of substituted 1,N6-etheno-2'-deoxyadenosine and 1,N2-etheno-2'-deoxyguanosine adducts by cis-2-butene-1,4-dial, a reactive metabolite of furan. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1607–1613. doi: 10.1021/tx049866z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson LA, Naruko KC, Predecki D. A reactive metabolite of furan, cis-2-butene-1,4-dial, is mutagenic in the Ames assay. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:531–534. doi: 10.1021/tx000065f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X, Gallogly MM, Mieyal JJ, Anderson VE, Sayre LM. Covalent cross-linking of glutathione and carnosine to proteins by 4-oxo-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1050–1059. doi: 10.1021/tx9000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Sayre LM. Long-lived 4-oxo-2-enal-derived apparent lysine michael adducts are actually the isomeric 4-ketoamides. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:165–170. doi: 10.1021/tx600295j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin D, Lee HG, Liu Q, Perry G, Smith MA, Sayre LM. 4-Oxo-2- nonenal is both more neurotoxic and more protein reactive than 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1219–1231. doi: 10.1021/tx050080q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurgens G, Lang J, Esterbauer H. Modification of human low-density lipoprotein by the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;875:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigolo CA, Di Mascio P, Medeiros MH. Covalent modification of cytochrome c exposed to trans,trans-2,4-decadienal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1099–1110. doi: 10.1021/tx700111v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isom AL, Barnes S, Wilson L, Kirk M, Coward L, Darley-Usmar V. Modification of cytochrome c by 4-hydroxy- 2-nonenal: evidence for histidine, lysine, and arginine-aldehyde adducts. J Amer Soc Mass Spec. 2004;15:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams MV, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Covalent adducts arising from the decomposition products of lipid hydroperoxides in the presence of cytochrome c. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:767–775. doi: 10.1021/tx600289r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, Tang X, Zhang J, Tochtrop GP, Anderson VE, Sayre LM. Mass spectrometric evidence for the existence of distinct modifications of different proteins by 2(E),4(E)-decadienal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:467–473. doi: 10.1021/tx900379a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu KY. Acid dissociation constant and apparent nucleophilicity of lysine-501 of the alpha-polypeptide of sodium and potassium ion activated adenosinetriphosphatase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6894–6899. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moro S, Chipman JK, Antczak P, Turan N, Dekant W, Falciani F, Mally A. Identification and pathway mapping of furan target proteins reveal mitochondrial energy production and redox regulation as critical targets of furan toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126:336–352. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.