Abstract

The engineered antibody approach to Huntington's disease (HD) therapeutics is based on the premise that significantly lowering the levels of the primary misfolded mutant protein will reduce abnormal protein interactions and direct toxic effects of the misfolded huntingtin (HTT). This will in turn reduce the pathologic stress on cells, and normalize intrinsic proteostasis. Intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) are single-chain (scFv) and single-domain (dAb; nanobody) variable fragments that can retain the affinity and specificity of full-length antibodies, but can be selected and engineered as genes. Functionally, they represent a protein-based approach to the problem of aberrant mutant protein folding, post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and aggregation. Several intrabodies that bind on either side of the expanded polyglutamine tract of mutant HTT have been reported to improve the mutant phenotype in cell and organotypic cultures, fruit flies, and mice. Further refinements to the difficult challenges of intraneuronal delivery, cytoplasmic folding, and long-term efficacy are in progress. This review covers published studies and emerging approaches on the choice of targets, selection and engineering methods, gene and protein delivery options, and testing of candidates in cell and animal models. The resultant antibody fragments can be used as direct therapeutics and as target validation/drug discovery tools for HD, while the technology is also applicable to a wide range of neurodegenerative and other diseases that are triggered by toxic proteins.

Keywords: Polyglutamine, intrabody, Huntington’s disease, single-chain Fv, nanobody

1. Introduction to intrabodies

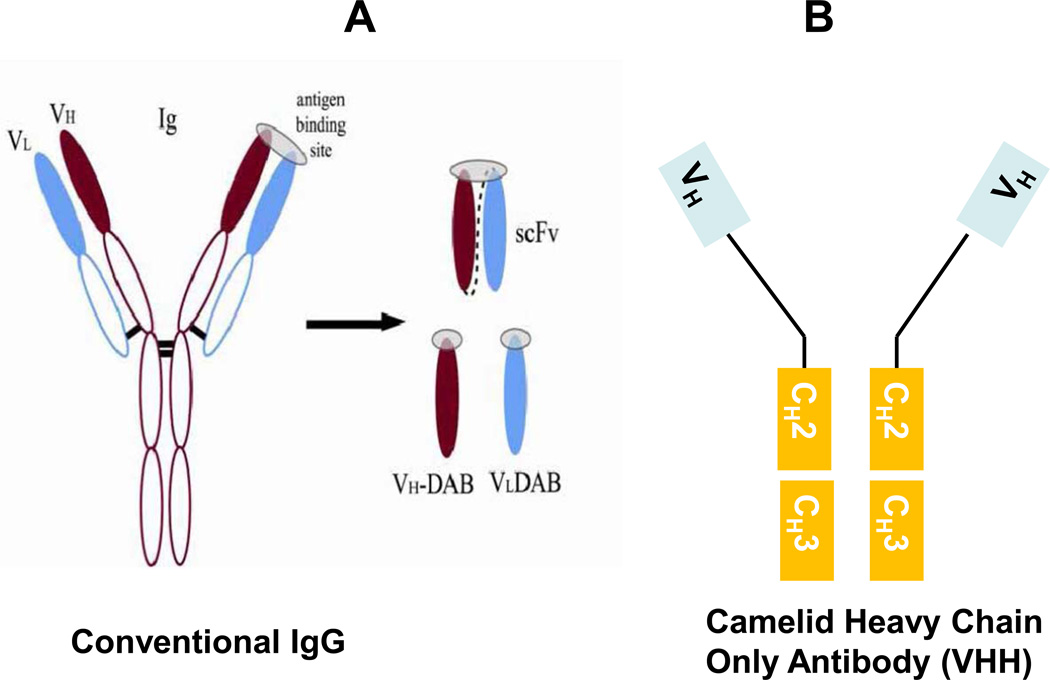

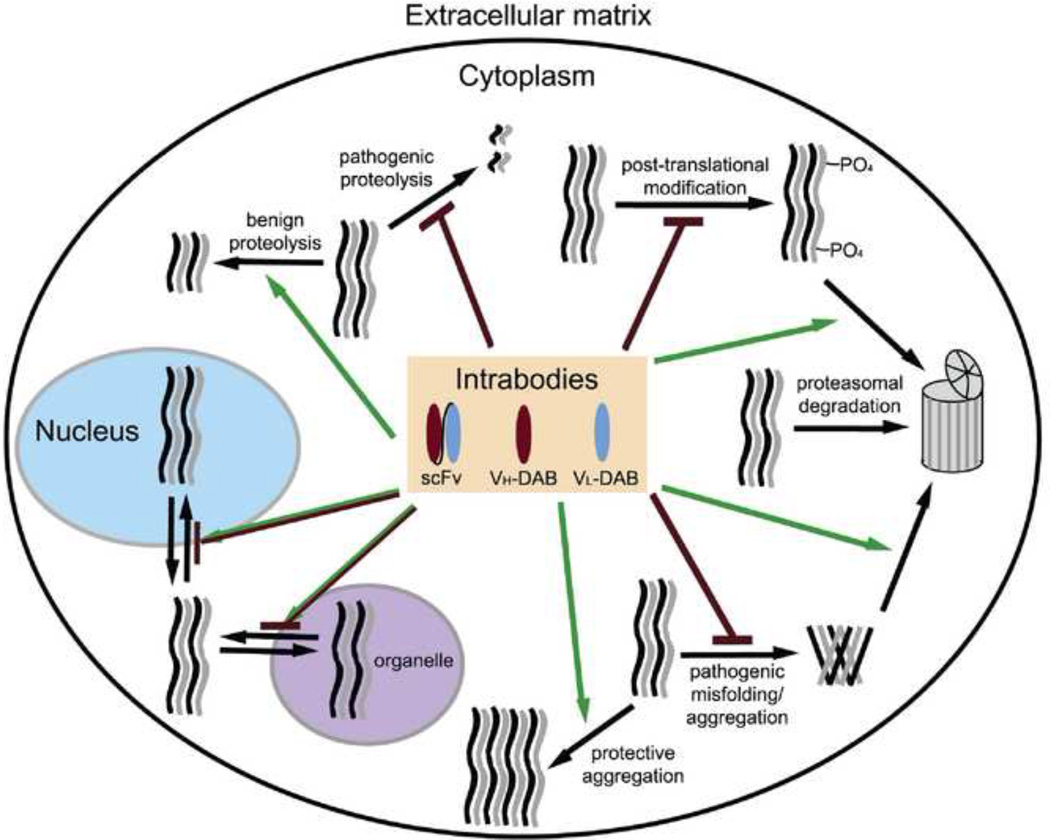

Intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) provide a protein-based approach to neutralizing the pathogenic characteristics of toxic misfolding proteins. Intrabodies are small, recombinant antibody fragments that target antigens intracellularly via the Fv variable regions that are responsible for antibody specificity. Fig. 1 diagrams the immunoglobulin protein and the binding regions that are used in intrabodies. These constructs exploit many of the advantages of conventional antibodies, including their high specificity and affinity for target epitopes. However, they are much smaller than full-length antibodies, they lack the potentially inflammatory Fc region, and they can be manipulated and delivered as genes or as proteins. This makes them powerful tools with which to target a wide range of pathways affected by pathogenic intracellular proteins (Fig. 2). Intrabodies were first reported in 1988 (Carlson, 1988). They have been studied extensively as potential therapeutics for infectious diseases (Aires da Silva et al., 2004; Doorbar and Griffin, 2007; Marasco et al., 1998; Mukhtar et al., 2009); and cancer (Groot et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2008; Tanaka et al., 2007). Our work and that of others have recently exploited the specificity and affinity characteristics of intrabodies to combat neurodegenerative diseases that share the cellular and molecular features of protein misfolding and aggregation (Cardinale and Biocca, 2008; Lynch et al., 2008; Messer et al., 2009; Messer and McLear, 2006; Miller et al., 2003; Zhou and Przedborski, 2008). In this article, we will discuss and update how intrabodies can provide novel therapeutics and target validations for neurodegeneration, with a focus on Huntington’s disease (HD) and related polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases.

Figure 1.

Diagram of antibody fragments.

a. Classic immunoglobulin and variable fragments; b. Camelid heavy-chain only antibody, and variable fragments.

Figure 2.

Potential sites of intrabody function. Green arrows represent increases in a process or function, while red ending in a line denotes inhibition. Note that alterations of subcellular localization can lead to either result. Some processes may be interdependent; e.g., blocking a post-translational modification could alter aggregation.

To create single-chain Fv (scFv; sometimes also abbreviated as sFv) intrabodies, the genes encoding the variable heavy (VH) and light chain (VL) binding domains of an antibody are cloned using reverse transcription. Antigen binding sites were initially thought to reside in the pocket between the VH and VL chains; however, examples of antigen binding that is exclusively on one or the other chain also seem common, with the second chain serving to stabilize the folding of the binding entity. A VH and a VL can then be joined with DNA encoding flexible linkers, generally (Gly4Ser) 3 or 5. Single-domain antibodies, also referred to as domain antibodies (dAbs), can consist of either VH or VL alone (Fig. 1a.).

One mechanism to generate an intrabody of known specificity starts with cDNA from a monoclonal antibody hybridoma cell line (Orlandi et al., 1989). This approach may have advantages for target validation where the epitope is known, but is less desirable when developing a human therapeutic, since the origin is mouse. Alternatively, cDNA from populations of human cells (e.g., naïve spleen, peripheral blood lymphocytes) can be utilized, generating phage or yeast surface-display libraries (Hockly et al., 2003; Holt et al., 2003; Jana et al., 2005; Paz et al., 2005). Libraries can then be biopanned in vitro, using a peptide to a known or suspected critical domain of a target protein, as illustrated for anti-N-terminal HTT (Colby et al., 2004b; Lecerf et al., 2001). For small proteins with variable conformations, monomers can also be used in the selections, as with alpha-synulcein (Emadi et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2004).

It is important to recognize that antibody fragments can bind to either a linear or a conformational epitope within the target sequence. The use of solid or solution-phase selections, along with specific conditions, can affect the outcome. It is also possible to biopan using a solid surface such as mica, with resolution of structures by atomic force microscopy built into the protocol (Shlyakhtenko et al., 2007). Not all in vitro selection conditions faithfully mimic intracellular conditions, and there may be specific differences among cell types. However, initial screening generally reveals valuable lead candidate intrabodies for therapeutic or mechanistic studies that can be further characterized in situ (Kvam et al., 2010). Another method that is designed to directly select for intrabodies that recognize intracellular conformers of target proteins in context is intracellular antibody capture, which uses an in situ two-hybrid screen to select for antigen-scFv interactions within the cytoplasm of yeast or within mammalian cells (Auf der Maur et al., 2001; Feldhaus et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2011; Visintin et al., 1999).

Affinity is a critical characteristic of intrabodies. Starting with a library that has been made from an individual with previous exposure to the antigen, or an animal that has been specifically immunized, offers the opportunity to take advantage of the natural maturation process to create high affinity. Using antibody engineering, affinity can also be “matured” in vitro via random or site-directed mutagenesis followed by iterative rounds of selection. Affinities with picomolar and even femtomolar binding have been selected (Boder and Wittrup, 2000; Colby et al., 2004a). However, there may be applications for which lower affinities are preferable, such as those designed to deliver target proteins for degradation, where recycling of the intrabody is advantageous; or intrabodies that are designed to interrogate specific intracellular conformations, where the protein might function differently with and without its bound antibody. In theory, it is also possible to engineer an intrabody with a high specific binding on-rate, and rapid (rather than slower) dissociation kinetics.

Single-domain antibodies (VH or VL) may have advantages since they are smaller and less bulky than scFvs. Specifically, camelid nanobodies are small heavy-chain-only antibody fragments (VHH) from alpacas, llamas and camels (Muyldermans et al., 2009) (Fig 1b). They are extremely stable, can fold correctly under a wide range of conditions, and are being tested as gene and protein therapeutics (Harmsen and De Haard, 2007; Roovers et al., 2007). A phage display synthetic library derived from such fragments yielded a VHH specific to Aβ fibrils (Habicht et al., 2007). Recently, a llama-derived VHH against misfolded mutant PABPN1, a protein implicated in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, was reported to suppress muscle degeneration in Drosophila (Chartier et al., 2009). Single-domain human VHs have been shown to offer protection in some cellular toxicity models (Shuntao et al., 2006); however, due to the presence of exposed hydrophobic patches (evolved to be shielded by the VL segment) on the surface, they usually are insoluble intracellularly. The process of camelization attempts to solve these insolubility problems through a replacement of such hydrophobic residues with hydrophilic counterparts from the corresponding Camelidae sequences (Davies and Riechmann, 1994). Such a replacement does have a positive effect on solubility, although affinity and immunogenicity issues must then be addressed.

2. Huntington’s and related polyglutamine diseases

2.1 Genetics and symptoms

Ten separate neurodegenerative disorders that are thought to be caused by abnormal mutant proteins with expanded CAG repeats, leading to abnormally long series of polyglutamines (polyQ) (La Spada and Taylor, 2010). The most common of these diseases is Huntington’s disease, an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder characterized by severe motor and variable psychiatric dysfunctions. The gene Huntingtin, HTT, was identified in 1993, using a Venezuelan population with an extremely high incidence (1993). The length of the polyQ expansion is roughly inversely correlated with age of onset, with 35–39 repeats showing late onset or incomplete penetrance, while > 40 CAG repeats contributed to a fully penetrant phenotype, with onset in early middle age. A mean of 60 CAG repeats has been observed in juvenile-onset patients, although the range can be quite large (Wexler et al., 2004).

2.2 Huntingtin and other expanded polyglutamine proteins

Mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT) with elongated polyQ undergoes abnormal folding, proteolytic cleavage to N-terminal fragments, and aggregation, with eventual appearance of neuronal and neuropil inclusion bodies (Crook and Housman, 2011; DiFiglia et al., 1997; Young, 2003). The gene is expressed ubiquitously, but non-dividing cells appear less able to clear the abnormal protein. Aggregates of mHTT are found throughout the brain, but are particularly concentrated in the striatum and cortex, regions that incur significant cell dysfunction and loss (Gutekunst et al., 1999). The medium spiny GABAergic neurons that compose approximately 80% of the caudate nucleus show particular vulnerability (Vonsattel et al., 1985). This causes disruption of the basal ganglia, loss of voluntary motor control and hyperkinesia, characteristic of the disease due to direct communication with the thalamus, cortex, and substantia nigra (Cepeda et al., 2007; Sieradzan and Mann, 2001). Aggregate formation and neuronal dysfunction in other regions may underlie the psychiatric symptoms of the disease. Although the role of mHTT aggregates in the pathogenic process remains a focus of much debate, attempts to reduce buildup of mHTT have yielded favorable outcomes on a number of measures (Dai et al., 2009; DiFiglia et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Lebron et al., 2005).

The endogenous function of wild type HTT remains elusive, although a number of systems have been implicated in the disease including axonal transport, transcriptional regulation, endocytosis, nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling, vesicular transport, and anti-apoptotic function (Caviston and Holzbaur, 2009; Imarisio et al., 2008; Zuccato et al., 2010). The wild type huntingtin protein appears to be predominantly full-length and cytosolic, with some evidence for a small fraction of nuclear HTT. Mutant N-terminal fragments often accumulate in the nucleus, where they may be responsible for transcriptional deregulation. Intrabody correction of the aggregation phenotype in discrete brain regions of HD animal models may help to inform our knowledge of the disease pathogenesis, in addition to allowing critical analyses of how extensively regional cellular correction of misfolding protein is clinically required. Details of the individual mouse models that have been used in intrabody correction studies are intercalated below in section 6.2.1. A review of the general aspects of the use of mouse models of HD, and their correlation with human disease is provided by Crook and Housman (Crook and Housman, 2011).

Similar results showing nuclear inclusions, transcriptional dysregulation, and interference with basic cellular processes have been seen in other polyQ repeat disorders such as spinobulbar muscular atrophy, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, and spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 17 (Becher and Ross, 1998; Holmberg et al., 1998; Paulson et al., 1997; Skinner et al., 1997). In most cases, the downstream pathogenic processes diverge, based on the protein itself and cell type in which the misfolding protein is accumulating. However, it would appear that any or all of these expanded polyQ proteins would be candidates for judiciously chosen intrabody therapies.

2.3 Rationale for a protein-based approach to reducing toxic protein levels

It is clear that an approach that reduces the level of toxic mutant protein has considerable appeal. There are currently two intervention points for such reductions – RNA interference, which will prevent protein from being translated, and protein/antibody or peptide-based reagents that will bind to the protein and counteract its toxicity via enhanced turnover and/or blocking of pathogenic function. Both face formidable issues of effective long-lasting delivery as genes or as direct gene products.

Recent advances, current status, and challenges of RNA approaches are comprehensively reviewed in papers by (Boudreau et al., 2011; Sah and Aronin, 2011). There are ongoing concerns about lack of specificity for the mutant allele, although there may be nucleotide differences that can be exploited in some kindreds. RNA interference is also subject to off-target toxic effects. However, studies have advanced to non-human primates for some anti-HTT RNA-targeting reagents, and clinical trials are in planning stages.

Intrabodies, in contrast, offer a protein-based approach to modulating the effects of the mutant protein. Given that they share specificity with antibodies, intrabodies are less likely to show off-target effects other than those that are generic to misfolded protein species (see section 3.1). Intrabodies also offer the potential to target post-translationally modified and conformationally distinct forms of the proteins. Although the most effective anti-HTT epitopes to date appear in both wild type and mutant forms of the protein, our data clearly show that the scFv-C4 intrabody preferentially affects exon 1 fragments, rather than the >3000AA full-length HTT (Miller et al., 2005). This may be due to either kinetics, epitope availability in vivo, or both. Given the absence of any reported physiological roles for the wild type HTT N-terminal fragments, any wild type fragments are likely to be transient degradation intermediates.

Thus, it appears that antibody engineering offers a range of protein-based options for designing intrabody therapeutics for HD and related diseases. Since both RNA and protein approaches may be delivered via gene therapy vectors, it may also be possible to combine both into one vector, if that would allow lower doses of each to avoid unwanted side effects.

Multiplexed therapies may also include small molecules, some of which are also directed to clearance of the toxic protein, although this modality is well-suited for reducing downstream effects (Varma et al., 2011). Small molecules have the advantage that many cross the blood brain barrier, and therefore can afford wide systemic distribution. Given that the HTT gene is expressed ubiquitously, adjunct systemic therapy may become important if gene therapy can correct individual brain regions, since the mode of action of small molecules is against broader cellular processes, specificity is much more difficult to achieve. However, it should be possible to optimize therapies, using lower doses of such chemical drugs in combination with biologic therapies.

3. Anti-HTT intrabodies have been used for proof of principle and target validation studies

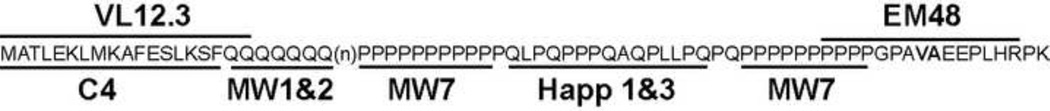

Huntingtin is a 348 kDa protein that is essential during embryonic development (Duyao et al., 1995). Full length HTT protein is subject to proteolytic processing by a number of proteases that produce a series of N-terminal cleavage products that have been shown to be toxic in various cellular and animal models of HD. Although HTT is a predominantly cytosolic protein, N-terminal fragments of mHTT have been reported to accumulate and to form inclusions in the cytosol and nucleus (Becher et al., 1998; DiFiglia et al., 1997; Sapp et al., 1997). Based on the fact that expression of only HTT exon 1 with an expanded polyQ stretch (mHTT exon 1) is sufficient to cause HD-like pathology in several models of HD, a variety of recombinant antibodies against the translation product of HTT exon 1 (Fig. 2) have been derived from phage or yeast surface-display libraries, as well as from hybridoma cell lines. Historically, intrabodies have been directed toward 3 separate regions of HTT exon 1: The N-17 AA, which form a highly conserved amphipathic alpha helix; the polyQ tract, which is the site of HD mutation; and the proline rich region that is C-terminal to the polyQ. The initial target of intrabody- based therapies was the expanded polyQ tract. However, both the Messer and Patterson labs found that intrabodies that recognize the misfolded expanded polyQ were shown to increase toxicity presumably by stabilizing a toxic conformation (Khoshnan et al., 2002; Lecerf et al., 2001). We and others therefore targeted the adjacent regions of the protein, which have the potential to provide an altered context to reduce misfolding, and/or to minimize abnormal protein interactions by the misfolded species. Subsequently, it was also discovered that these regions are subject to critical post-translational modifications which can affect disease. This enhances our understanding of how these intrabodies function for future engineering, while serving as target validation for specific sequences.

3.1 Intrabodies that target amino acids 1–17 (AA 1–17) of HTT

The N-terminal 17AAs of HTT play an important role in HTT function and HD pathology (Atwal et al., 2007; Cornett et al., 2005; Omi et al., 2008; Rockabrand et al., 2007). This 17 amino acid domain has been show to be involved with mitochondrial association, and co-localization with the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum (Rockabrand et al., 2007). The N-17AA along with expanded polyQ enhances aggregation, while deletion of the N17 AA results in nuclear localization and enhanced toxicity (Rockabrand et al., 2007). The first 18AA of HTT form an amphipathic alpha helix, which is involved with the subcellular localization of HTT (Atwal et al., 2007). Substitution of a Proline, a helix breaking AA, for Methionine at AA #8 disrupts HTT aggregation, but greatly enhances mHTT induced toxicity (Atwal et al., 2007). The N 17AA of HTT is also the site of several post-translational modifications such as acetylation (Aiken et al., 2009), SUMOylation (Steffan et al., 2004), ubiquitylation, and phosphorylation (Aiken et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2009). Serines 13 and 16 of mHTT exon 1 can be phosphorylation targets. Phosphomimetic substitution of serines 13 and 16 to Asparitc acid in full length mHTT BAC transgenic mice prevented behavioral deficits, mHTT aggregation, and neurodegeneration (Gu et al., 2009). Threonine 3 of mHTT exon 1 has also been show to be phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo, and is believed to be protective (Aiken et al., 2009). Interestingly, phosphorylation of Threonine 3 appears to be retarded in HD-susceptible cell lines such as ST14A compared to HeLa cells which are not as sensitive to mHTT exon 1-induced toxicity.

The first intrabody that successfully counteracted in situ length-dependent mHTT exon 1 aggregation and toxicity was scFv-C4 (Kvam et al., 2009; Lecerf et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2005; Murphy and Messer, 2004). This intrabody was derived from a naïve human spleen scFv phage-display library by panning with a peptide of the N-terminal amino acid residues 1–17 of HTT. Remarkably, scFv-C4 displays excellent intracellular folding properties (Kvam et al., 2010). Critically, scFv-C4 preferentially binds to soluble mHTT N-terminal fragments, and has only a weak affinity to endogenous full length HTT, which is possibly due to epitope inaccessibility to full-length wild type HTT (Miller et al., 2005). Because long-term reduction of full-length wild type HTT can exacerbate neurological degeneration, it is preferable that intrabody and RNAi based therapies preferentially target mHTT and N-terminal fragments (Auerbach et al., 2001). scFv-C4 appears to neutralize the toxic effects of mHTT exon 1 by stabilizing N-terminal mHTT exon 1 fragments in a non-toxic conformation.

scFv-C4 has been tested in vivo in both Drosophila and mouse models of HD, as described more completely below in section 6. In summary, the flies were fully protected into young adulthood, with complete correction of eclosion, reduction of aggregates, and a 30% increase in lifespan. The intrabody effects became less robust as the flies aged. A similar effect was found with AAV gene therapy delivery to the striatum of the HDR6/1 mouse model. Cellular protection of striatal neurons was dramatic with young adult injection for several weeks; however, the aggregates eventually increased with time. Additional antibody engineering, better delivery methods, and combinatorial approaches can be used to increase efficacy.

Colby et al. used a more engineering-based approach to the anti-HD intrabody problem. The intrabody that would eventually become known as VL12.3 underwent two series of engineering. Initially a variable light chain only single-domain intrabody (VL) was derived from a non-functional scFv by performing affinity maturation and binding site analysis on the yeast cell surface (Colby et al., 2004b). This VL intrabody, selected against HTT AAs 1–20, was a mild inhibitor of HTT aggregation (Colby et al., 2004b). To enhance biological functionality in the cytoplasm, the VL intrabody was then engineered to fold in the reducing environment of the cell via a series of substitutions of cysteine for hydrophobic residues, followed by additional affinity improvement (Colby et al., 2004a). VL12.3 binds within the N-terminal amino acid residues 1–20 of HTT and it reduces mHTT exon 1-induced aggregation and toxicity in vitro (Colby et al., 2004a), while not altering the turnover of mHTT exon 1 (Southwell et al., 2008). When co-expressed with mHTT exon 1 in a lentiviral model of HD, VL12.3 improved behavior and neuropathology (Southwell et al., 2009). However, VL12.3 appears to block cytoplasmic retention of HTT (Southwell et al., 2008), resulting in higher levels of antigen-antibody complex in the nucleus, which may increase toxicity in vivo in HDR6/2 mouse model (Southwell et al., 2009). Because VL12.3 causes nuclear retention of mHTT, it may need to be delivered prior to the onset of aggregation of mHTT exon 1 fragments to have a therapeutic effect. It is therefore extremely interesting that scFv-C4, which was selected against 1–17, appears to bind to the far N-terminus, AAs 2–12 (Thumfort and Ingram, pers. Comm.). This would block Threonine 3 and possibly serine 13 phosphorylation. VL12.3, on the other hand, was selected against a peptide that included AAs1–20. The epitope has been identified as including AAs 5–18 (Schiefner et al.). This binding therefore is likely to block the phosphorylation at serine 13 and serine 16, which fits well with in situ and in vivo observations that the VL12.3-HTT exon 1 complex is preferentially found in the nuclear compartment. It also suggests that there may be additional effects on the mHTT exon 1 if the modifications are blocked, which is the equivalent of phospho-ablation. SUMO effects on the N-17 AA region may likewise be blocked by VL12.3 binding.

3.2 Intrabodies and peptide-binding proteins that target polyQ

In 2001, the Patterson lab developed eight anti-HTT monoclonal antibodies for use as diagnostic tools to study HD. Based on epitope mapping, MW1–6 specifically binds to the polyQ domain of HTT exon 1, with MW1–5 showing a preference for expanded polyQ, and does not detectibly bind other poly-Q containing proteins (Ko et al., 2001). These monoclonal antibodies express differential staining patterns for mHTT based on subcellular location (Ko et al., 2001). In an effort to produce a protein to prevent the abnormal misfolding of mHTT, the antigen binding domains of MW1–8 monoclonal antibodies were PCR amplified and cloned into a phage display vector. The phage were isolated from immunoblots that contained a mHTT exon 1 glutathione S-transferase (GST)-protein with 67 polyQ repeats (Khoshnan et al., 2002). Interestingly, scFv- MW1 and scFv-MW2 intrabodies accelerated cell death and aggregation in HEK293 cells cotransfected with mHTTex1–103Q-eGFP plasmid (Khoshnan et al., 2002). The epitope specificity of these scFv’s is based on MW1 and MW2 mAbs, which have been shown to bind peptides containing greater than six glutamines. MW1 and MW2 mAbs exhibit a preference for mHTT with an expanded polyQ tract over wild type HTT (Ko et al., 2001). Crystal structure analysis of scFv-MW1 bound to polyQ suggests that scFv-MW1 binds to an extend coil-like structure of expanded polyQ that is in accordance with the linear lattice model, where expanded polyQ increases the number of binding sites within the polyQ tract (Li et al., 2007). scFv-MW1 binds to diffuse expanded polyQ with a higher affinity than to shorter polyQ tracts found in wild type HTT or other polyQ containing proteins with unexpanded polyQ repeats (Li et al., 2007). The mode of action for scFv-MW1 and scFv-MW2 is currently unknown; however, it is likely that they are stabilizing mHTT in a toxic conformation, similar to the pan-specific anti-fibrillar scFv-6E reported in Kvam et al (Kvam et al., 2009). This fibrillar conformation is characteristic of expanded, but not normal, polyQ.

Based on the premise that peptide-binding proteins, similar to conventional antibodies, can recognize specific protein conformations, Nagai et al. screened an eleven-amino acid combinatorial phage display peptide library to identify peptides that that preferentially bind pathologic-length polyglutamine domains (Nagai et al., 2000). Six polyglutamine binding peptides (QBP1–6) were identified that shared a tryptophan-rich motif; with QBP1 having the greatest differential binding affinity to pathologic length polyQ compared with normal length polyQ (Nagai et al., 2000). QBP1 has been shown to inhibit thioredoxin-polyglutamine (Thio-Q62) protein aggregation in vitro, polyglutamine-yellow fluorescent protein (polyQ-YFP)- dependent aggregation in situ, and cell death in COS-7 cells (Nagai et al., 2000). Similar to many anti-HTT intrabodies, QBP1 does not have the ability to breakdown a preformed aggregate, although it can inhibit further aggregation (Ren et al., 2001). QBP1 interacts with polyQ expanded proteins at the level of the monomer, presumably by preventing the formation of the β-sheet conformation (Nagai et al., 2007). Importantly, the inhibitory effects of QBP1 appear to be stronger for shorter polyQ repeats (Q45-YFP > Q57-YFP > Q81-YFP). A tandem repeat of QBP1 has been shown to increase the median lifespan of a transgenic fly model that showed weak expression of Machado–Joseph Disease (MJDtr-Q78W) in the CNS from 5.5-days to 52-days (Nagai et al., 2003). In a similar study, oral administration of Antennapedia protein transduction domain, which enables the fusion protein to cross the cell membrane, fused to QBP1 (Antp-QBP1) reduced neurodegeneration in MJDtr-Q78W Drosophila fly model (Popiel et al., 2007). At 15 days, the median lifespan was improved from 5% to 50% in the Antp-QBP1 treated flies (Popiel et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the efficacy of QBP1 has not been examined in HD fly models, and cannot be compared to the anti-HD scFv C4 intrabody. Delivery of Antp-QBP1 through intraperitoneal and intracerebroventricular injection was unable to efficiently cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) in HD R6/2 mice (Popiel et al., 2009). Bauer et al. showed that recombinant adeno-associated virus (Serotype 2) intra-striatal delivery of QBP1 reduced aggregation of mHTT by 26%, and improved rotarod performance by 14% in R6/2 mice (Bauer et al., 2010). The future identification of chemical analogues of QBP1 that can pass through the BBB represents a potential therapeutic molecule for the many polyQ diseases. Further investigation is needed to understand why QB1 and scFv-MW1, scFv-MW2, and scFv-6E have differential effects on polyQ associated toxicity.

3.3 Intrabodies that target HTT exon 1 regions C-terminal to the polyQ

Immediately C-terminal to the polyQ domain of the HTT exon 1 gene product is a proline-rich region, which has been shown to be an important determinant of mHTT fragment aggregation. The proline-rich region consists of a polyproline (polyP) stretch that is immediately followed by a unique proline-rich domain, another polyP stretch, and an additional 13 amino acids. Deletion of the proline-rich domain was shown to accelerate aggregation of mHTT fragments (Qin et al., 2004; Rockabrand et al., 2007). The Patterson lab has developed a series of intrabodies against the proline-rich region of HTT. The first generation of anti-HTT proline-rich region intrabodies, was derived from the monoclonal antibody MW7, which binds to the two polyP stretches of HTT exon 1 gene product (Ko et al., 2001). scFv-MW7 has been shown to reduce mHTT-induced aggregation and enhance survival in an HEK293 culture model of HD (Khoshnan et al., 2002). Because MW7 has the potential to bind other proteins containing a polyP stretch, a second set of anti-proline-rich domain intrabodies (Happ 1 and Happ 3) was selected from a non-immune human recombinant scFv phage library (Southwell et al., 2008). In contrast to scFv-MW7, the Happ intrabodies bound via a single light-chain domain. They prevent mHTT induced aggregation and toxicity at a 2:1 ratio of intrabody to HDex1–103Q versus a 4:1 ratio for scFv-MW7 (Southwell et al., 2008). Happ1, Happ3, and scFv-MW7 intrabodies accelerated the turnover of mHTT in HEK293 cellular model of HD (Southwell et al., 2008). It appears that the mechanism of Happ1- induced turnover of mHTT is due to enhanced calpain cleavage of the first 15aa of mHTT followed by lysosomal degradation (Southwell et al., 2011). Intrastriatal AAV delivery of Happ1 was found to be beneficial in a variety of in vivo assays in diverse mouse models, further described in section 6.2.3 (Southwell et al., 2009; Southwell and Patterson, 2011).

mEM48 is a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes human mutant HTT in the C-terminus of HTT exon 1. Therefore, this antibody is valuable for immunocytochemical studies of aggregation in HD mouse models as mouse vs. human mHTT can be distinguished (Wang et al., 2008). When expressed as an intrabody, scFv- EM48 suppresses the cytoplasmic, but not nuclear, toxicity of mHTT in HEK293 cells. It also reduces mHTT distribution in neuronal processes and ameliorates neurological behavior in HD mice. In vitro studies suggest that one of the protective mechanisms of this intrabody is increased ubiquitination and degradation of cytoplasmic mutant HTT (Wang et al., 2008).

3.4 Conformation-specific intrabodies

Intrabodies that bind to specific conformers of misfolded proteins are a potential source of disease-specific therapeutics, as well as in situ probes of cellular presence and localization of distinct misfolded species. Relevant to polyQ, one set of conformation-specific scFvs has been generated by combining phage library display techniques with atomic force microscopy to select antibodies that recognize structurally distinct oligomeric and fibrillar misfolded protein intermediates in vitro (Barkhordarian et al., 2006). Using this method, scFvs against oligomeric and fibrillar forms of α-synuclein, which are associated with Lewy body formation and neurotoxicity in PD, have been isolated (Barkhordarian et al., 2006; Emadi et al., 2007). We have been able to use one of these intrabodies as a tool to probe the role of fibrillar aggregates in polyQ pathogenesis (Kvam et al., 2009). The anti-fibrillar scFv-6E cross-reacts with HTT and Ataxin3 as an intrabody. This cross-reactivity was not surprising, since conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies against β-amyloid cross-react with oligomeric and fibrillar species of non-homologous neurotoxic proteins like α-synuclein, prion peptide, and polyQ (Kayed et al., 2003; O'Nuallain and Wetzel, 2002). When expressed in the cytoplasm of striatal cells, the scFv-6E fibril-specific intrabody co-localizes with intracellular aggregates of misfolded HTT exon 1 and ataxin-3, significantly increasing the aggregation of both. Using this intrabody as a tool for modulating the kinetics of amyloid fibril formation, we show that this increase in aggregate formation of HTT exon 1 is not cytoprotective in striatal cells, but it increases oxidative stress and cell death. Instead, cellular protection is achieved by suppressing aggregation using the monomer-binding intrabody scFv-C4. Similar effects on cytotoxicity are observed following conformational targeting of wild type vs mutant human ataxin-3, which aggregates through both expanded polyQ and non-polyQ domains (Kvam et al., 2009). These studies clearly show that some forms of polyQ fibrillar aggregation are pathogenic, and they may provide an explanation for previous studies that showed that scFvs selected directly against expanded polyQ domains were also toxic as intrabodies. Unfortunately, the anti-oligomeric scFvs isolated to date have been too unstable intracellularly to test in a similar manner. Hopefully, some combination of engineering to increase intracellular folding and a new set of VHH camelid constructs will yield tools to follow the formation and processing of oligomeric species in situ.

Summary statement

The intrabody data to date suggest that intrabodies targeting protein domains adjacent to the polyQ may in fact be altering the context for the misfolding via blocking of post-translational modifications. These findings also suggest that the sites of post-translational modification outside exon 1 of HTT, and in other mutant polyQ proteins, would make excellent intrabody targets.

4. Selection and engineering methods

4.1 Improving intracellular protein folding

Protein folding is a critical issue for scFvs and dAbs that are to be expressed and retained within cells as intrabodies. Many scFvs are intrinsically unstable when expressed within the complex reducing environment of the cytoplasm, largely due to the redox inhibition of disulfide bond formation. This affects the initial solubility, stability, and whether the binding site is correctly folded for maximum affinity and specificity. Camelid VHH intrabodies have a higher probability of correct intracellular folding, although they do contain cysteines that can form disulfide bonds (Colby et al., 2004b; Saerens et al., 2005). The method that is designed to directly select for stable intrabodies in a high-throughput manner is intracellular antibody capture, which uses an in situ two-hybrid screen to select for antigen-scFv interactions within the cytoplasm of yeast (Auf der Maur et al., 2001; Colby et al., 2004c; Feldhaus et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2011; Visintin et al., 1999). Alternatively, the antigen-binding complimentary determining regions of an unstable scFv can theoretically be “loop- grafted” into several well-characterized intrabody consensus scaffolds that are reported to exhibit improved intracellular folding and stability (Ewert et al., 2004). This method still has multiple uncertainties, since the complimentary determining region also contribute to the intracellular folding. Unstable intrabodies have also been engineered for improved folding using amino acid replacement of cysteine residues in order to generate electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions that compensate for a loss of disulfide bonds (Colby et al., 2004a). The described method required significant affinity maturation via random mutagenesis once the non-cysteine-containing framework was optimized. In work submitted for publication by Dr. A. Skerra and colleagues, the crystal structure of this stable VL bound to HTT exon 1 AAs1–18 was solved. The binding site includes most of the AA5–18 region, which appears to be binding on the VL hydrophobic face that would normally bind to the VH. The discovery of this mode of binding may have more general applications to engineering designed anti-HTT intrabodies.

When considering a series of candidate intrabodies, there are some calculations that can be used as rough predictors of the most likely soluble proteins. We have observed that the well-documented net negative charge for soluble intracellular proteins is an important determinant of intrabody solubility, and that total hydrophilicity (GRAVY) is a secondary correlate of aggregation propensity for weakly acidic intrabodies (Kvam et al., 2010). However, even within these frameworks, our ability to predict solubility is limited. Of the choices above, the optimal appears to be selection of VHH camelid nanobodies from an immune library (alpaca or llama), at least with our current knowledge of intracellular folding. Recently, the Tessier lab reported that three charged mutations within CDR1 and one charged mutation adjacent to CDR1 improved the solubility of an aggregation-prone construct (Perchiacca et al., 2011). As the ligand for this VH is unknown, additional studies will be required to establish the effects of this novel class of substitutions on binding specificity and affinity. It is also the case that intracellular folding and the aggregation measured in these assays do not always overlap, but the approach is worth considering.

4.2 Enhancing efficacy with bifunctional intrabodies

Intrabodies represent a versatile and powerful option for modulation and neutralization of intracellular gene products. Not only have intrabodies been found to bind to antigens with high specificity and affinity, but engineered intrabodies have been shown to successfully retarget antigens to various cellular compartments, which can further enhance their efficacy (Lobato and Rabbitts, 2003; Perez-Martinez et al., 2010; Persic et al., 1997; Steinberger et al., 2000). Specifically, bifunctional-intrabodies have been designed to clear potentially toxic molecules by selectively targeting proteins for degradation (Melchionna and Cattaneo, 2007; Sibler et al., 2005). Clearance of misfolded proteins generally occurs through two major pathways: the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagic lysosomal (Li et al., 2010b; Li and Li, 2011). Therefore, bifunctional-intrabodies, synthetic peptide-binding proteins and activation of chaperone proteins have been used to selectively degrade intracellular proteins through proteasomal (Zhou et al., 2000) and autophagic/lysosomal pathways (Bauer et al., 2010).

4.2.1-- PEST targeted degradation of proteins through the proteasome

The UPS is believed to play an important role in the degradation of soluble mHTT (Li et al., 2010a; Li and Li, 2011). Since N-terminal mHTT fragments have been shown to accumulate and form inclusions in the nucleus of cell, strategies to selectively enhance the clearance of mHTT through the UPS could take advantage of the fact that proteosomes are localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm, while autophagy is limited to the cytoplasm. Proteins containing a PEST motif, an enriched region of amino acids Proline (P), Glutamic Acid (E), Serine (S), and Threonine (T), typically have a short half life, and are degraded by the proteasome. Mouse Ornithine Decarboxylase, a cytosolic enzyme that is involved in the biosynthesis of polyamines, contains a PEST motif and is rapidly degraded in mammalian cells (Ghoda et al., 1989). The half lives of green fluorescent protein (Li et al., 1998) and luciferase (Leclerc et al., 2000) were significantly reduced upon fusion of the Mouse Ornithine Decarboxylase PEST motif (amino-acids 422–461) to the C-termini. Sibler et al. transferred the Mouse Ornithine Decarboxylase PEST motif to the anti-β-gal scFv-13R4 intrabody, which rendered the intrabody unstable. However, the proteasome was unable to degrade the large intrabody-antigen complex (Sibler et al., 2005). Although β-gal has been commonly used as a target for proof of principle, researchers have only observed modest degradation of the protein; therefore β-gal may not be an optimal protein to test in this experiment due to its large size. Recently, we fused Mouse Ornithine Decarboxylase PEST motif to anti-HTT scFv-C4 and observed significant turnover of antigen, while not changing solubility of the intrabody. It is important to note that scFv-C4 maintains mHTT in a monomeric soluble conformation, which allows the PEST motif to target mHTT exon 1 for proteasomal degradation. Aggregated N-terminal HTT fragments have been reported to be resistant to degradation by the UPS (Verhoef et al., 2002). As expected, subsequent fusion of the PEST motif to a second intrabody, scFv-6E, which binds only to fibrillar HTT exon 1, failed to enhance degradation of mHTT exon 1. Therefore, careful consideration of the antigen conformation is important when utilizing intrabody-PEST mediated degradation.

Surprisingly, our data suggest that scFv-C4-PEST and scFv-6E-PEST intrabodies, in the absence of antigen, do not undergo appreciable turnover. This is in contrast to the anti-β-gal scFv-13R4-PEST intrabody, which is readily degraded. scFv-C4 , scFv-6E, and scFv-13R4 belong to different framework families; in addition, the framework for scFv-13R4 contains several random point mutations that deviate significantly from consensus antibody framework sequences to enhance solubility (Martineau et al., 1998). The possibility exists that the mutated framework sequences of scFv-13R4 may account for the apparent destabilization of scFv-13R4-PEST. With regards to the ability of the different intrabody-PEST fusion constructs to target proteins to the proteasome, properties of the intrabody also must be taken into consideration. It is clear from our work that there may be many classes of intrabodies that are not completely destabilized by the addition of a PEST motif, and testing of these constitutively active intrabody-PEST fusion constructs is quite straightforward in tissue culture. This will allow future empirical determination of the most effective fusion constructs for the selective proteolytic degradation of intracellular proteins.

4.2.2-- Selective activation of chaperone mediated autophagy

An alternative strategy for reducing the levels of mHTT has involved the induction of autophagic/lysosomal pathway of intracellular protein degradation (Ravikumar et al., 2002; Rose et al., 2010; Sarkar and Rubinsztein, 2008). The most common types of autophagy are macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), which are classified based on the mechanism that mediates the delivery of cytosolic cargo to lysosomes for degradation (Bejarano and Cuervo, 2010; Mizushima et al., 2008). The global induction of autophagy is limited to macroautophagy and microautophagy pathways and is complicated by potential off-target side effects. Bauer et al, fused heat shock cognate protein 70 (HSC70) binding motifs (KFERQ and VKKDQ), which target ligands to the lysosome for degradation by chaperone-mediated autophagy, to QBP1 (QBP1-HSC70BM) (Bauer et al., 2010). In contrast to QBP1, when QBP-HSC70BM was transduced into HDR6/2 mice there was ~80% reduction of aggregation, a 29% increase in lifespan, a 25% increase in body weight, and a 50% increase in rotarod performance (Bauer et al., 2010). Selective activation of CMA has a specific advantage over the global induction of autophagy in that it can potentially limit unwanted off-target side effects. Fusion of HSC70BM to intrabodies may have distinct advantages over fusion to polyQ binding peptides. For example, the very high specificity of intrabodies should minimize off-target effects due to the presence of polyQ tracts in other mammalian proteins. Intrabodies derived from human scFv libraries are also less likely to provoke an immune response in clinical applications compared with novel peptides. As proof in principle, we have fused the HSC70BM to scFv-C4, and see a 30% reduction of soluble HTT, which is similar to results of QBP1-HSC70BM (Bauer et al., 2010).

5. Gene and protein delivery options

5.1 Delivery via gene therapy

A significant advantage of engineered recombinant antibody fragments is that they can be delivered as genes. There are currently a large number of gene therapy trials for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, delivering a range of growth factors, other trophins, and enzymes, along with a smaller set of gene replacement studies (Lentz et al., 2011). These have provided a wealth of human and animal studies on viral vector safety, spread, and susceptibility to pre-existing and induced immune reactions. For a very recent review covering the range of vectors, advantages and disadvantages, and disease approaches; see Bowers et al, 2011 (Bowers et al., 2011). At this time, AAV appears to be the safest and least immunogenic for current human CNS clinical trials. It is capable of transducing non-dividing cells, transgene synthesis appears to persist for months to years, and it there are several capsid variants that can be used to potentially modulate the specific cells transduced and retrograde transport. (Most maintain the internal AAV2 structure, and are therefore designated AAV2/n, where n=capsid.)

Three groups have recently published studies using AAV to deliver intrabodies via intracranial brain injections. The two HD groups, Messer and Patterson, using AAV2/1, have shown successful transduction of striatum with direct injections, as described in detail below in section 6.2. Sudol et al (Sudol et al., 2009) used AAV2/2 to deliver genes encoding intrabodies targeting amyloid beta early in the course of an Alzheimer’s disease model. This strategy was more successful in ameliorating the mutant mouse phenotype when the intrabody was fused to an ER retention signal, underlining the power of adding additional cellular targeting signals to intrabodies.

Effective intrabody gene delivery to human brains will need to include high numbers of transduced cells, broad spread, and would ideally allow systemic administration. The use of optimal promoters and self-complementing AAV vectors offers promise in this direction (Allay et al., 2011). One drawback to the self-complementing vectors is that the size of the insert is halved to approximately 2300nt (McCarty et al., 2001). Fortunately, the size of the intrabodies is small enough (250AAs for scFvs and 120–140 for dAbs) that the coding regions can be readily accommodated within these AAV vectors, even with complex promoters, and bispecific or bifunctional constructs. Newer capsid constructs, particularly AAV9, have been reported to spread more efficiently, and in some cases expression is seen in brain neurons and glia with systemic delivery (Cearley et al., 2008; Foust et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2011; Klein et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008).

5.2 Protein delivery

Delivery of therapeutic intrabodies as purified proteins would be most advantageous if pulsed treatments are sufficient to clean out the accumulating protein from affected cells, effectively resetting the clock. When exogenously delivered, even relatively long-lived proteins that have to act in the cytoplasm will eventually break down. This will restrict fully continuous treatment by proteins or peptides to mechanisms that are successful when administered at intervals, or to those where there can be implants of pumps or secretory cell lines. The additional challenge for neuronal polyQ diseases is that the targets are within neurons and within the brain. This therefore requires a mechanism to transit the blood brain barrier, a mechanism to spread to multiple affected brain regions, and a mechanism to translocate into cytoplasm of neurons (and possibly other cells) in an active form. In theory, engineered antibodies have the advantage that they can be synthesized to be bifunctional or bispecific. In particular, antibodies to cell surface receptors or channels can effect internalization under limited conditions, and can be used to carry cargo proteins (including other antibodies) or other molecules with them. In one example, Zhan et al have shown that a scFv derived from a mouse anti-DNA autoantibody, monoclonal antibody 3E10, can ferry HSP70 into neuronal nuclei via the equilibrative nucleoside transporter. This construct can be administered systemically (rat tail vein) in a stroke model, where the BBB is relatively permeable (Zhan et al., 2010). Critical points about this study are that the non-ischemic control brains did not accumulate the Fv-HSP70 protein, and that the neuronal nuclei from the ischemic brains were strongly immunopositive. Whether the BBB in HD and similar diseases is leaky is still a matter of debate. However, it is reasonable to assume that early treatments would be faced with an intact BBB, suggesting that this complex would best be administered intracranially. Most of the anti-DNA autoantibodies that have been identified have a strong tendency to accumulate in the nucleus, which is not desirable for an anti-HD intrabody, since the antigen (mHTT) would then be preferentially nucleus during any brief periods when it is dissociated from the antibody. However, if the construct also includes a functional domain to induce turnover in proteasomes, the nuclear proteasomes may be sufficient to clear the complex prior to dissociation and release of mutant antigen protein in an undesirable cellular compartment.

Transferrin receptor is also found on neurons, may be increased in HD, and can be a target for BBB permeability. A recent pair of papers described an approach using a chimeric antibody where one chain was engineered to bind to the Transferrin receptor with modest affinity, allowing it to saturate the BBB membrane, and then be delivered into the brain parenchema (Atwal et al.; Yu et al.). When combined with a second chain that inhibited Beta secretase, systemic delivery in a mouse could reduce Beta secretase activity in the brain. This general approach is promising, although difficulties with genetic specificity of the anti-transferrin receptor antibodies (among species and possibly in different human genetic backgrounds) may require pharmacogenomic optimization of such therapies. It is also not clear that the levels of delivered antibody will be high enough to be therapeutically efficacious. Chimeric antibodies may themselves stimulate immune responses, particularly in patients that are already challenged with an enhanced inflammatory response. However, with increasing knowledge of the systemic effects of the polyQ diseases, the transport processes in normal and mutant BBB and brain cells, and the structures that are optimal for intracellular activity, such deliveries may become possible.

6. Testing of candidates in animal models

6.1 Drosophila melanogaster

6.1.1-- Techniques for neurodegeneration studies

The Drosophila melanogaster has been used for over a hundred years to study and elucidate genetics. The fruit fly has been pivotal in identifying gene mutations, chromosomal mapping (Sturtevant, 1913), studying development (Lee and Luo, 2001; Lewis, 1978; Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980) and elucidating plasticity of the neuromuscular junction (Seabrooke and Stewart, 2011; Weyhersmuller et al., 2011; Wilhelm et al., 2010). Recently, the fruit fly has been utilized as a model organism to study human disease, and bridge work from cell culture to organismal models. Flies have a short, predictable life cycle including an embryonic stage, three larval stages, and a pupal stage, followed by eclosion into adulthood with a lifespan of approximately 60 days at 25° Celsius. The rate of development and lifespan can be slowed by simply changing the temperature, making fly husbandry convenient. A methodology that is commonly exploited in fly crosses is the UAS-GAL4 system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993; Duffy, 2002), which has been valuable for HD studies. Genes of interest can be cloned downstream of an upstream activating sequence (UAS) and will be transcribed in specific tissues under the direction of promoters fused to the transcriptional activator GAL4 protein. GAL4 is a yeast protein consisting of an activator and DNA binding domain and is not normally found in other organisms, but has been utilized to study gene expression in organisms such as the fruit fly. Collaborators have made a large variety of GAL4 flies that can drive expression of UAS and their gene of interest in specific tissue. This breeding scheme is especially valuable for modeling diseases that affect neurons, since the system offers a choice to express only in the neuronal cells of the eye, or pan-neuronally. Setting up crosses for each generation also alleviates potential problems that can arise from genetic instability and background variations that are seen in mouse models. Mutant genes such as HTT, under transcriptional control of UAS, can be carried without being expressed until GAL4 is present, thus evading breeding problems that can result from sick flies. Traditionally, transgenes were introduced into the fly embryo using P-elements, a transposable element in fruit flies. Although, a powerful vehicle for DNA integration in the fly, P-elements are inserted into the genome randomly. Recently, fly transgenic engineering has been optimized so that transgenes can be incorporated into targeted landing sites on any of the four fly chromosomes, allowing researchers to introduce disease genes into non-essential regions of the genome and circumvent chromosomal positioning effects that can influence severity of expression (Bateman et al., 2006; Bischof et al., 2007; Venken et al., 2006).

Drosophila has a number of benefits as a model organism for studying neurodegenerative diseases. The model offers a rapid secondary screening mechanism for efficacy of therapeutics that appear promising in cell culture. Global neurodegeneration can be easily assayed, while genetics and potential drug regimens can be manipulated and tested inexpensively. Importantly, for drug studies, the flies have a blood brain barrier. A glial sheath forms septate junctions and insulates the nerve cord against the potassium-rich hemolymph (Daneman and Barres, 2005). This is particularly important when choosing drugs that target CNS disorders. Also, high throughput genetic screens can be performed to identify enhancers and suppressors that are can modify a disease phenotype. However, careful consideration must be given to the approaches that are applied to the fly when transitioning to mammalian models. Their immune response and metabolism are notably distinct. Although overall neuronal susceptibility can be assessed in the fly, the specific areas of the brain that are most vulnerable in HD cannot be studied, as the fly brain lacks overall complexity compared to the mammalian brain. However, even though the mode of delivery of gene therapy vectors must be evaluated in higher organisms such as mice and primates, the flies have offered important data for HD intrabody studies, and models of other polyQ diseases are also available.

6.1.2-- HD Fly

To date, several models of polyglutamine repeat disorders have been studied in Drosophila (Hirth, 2010). The first HD fly engineered to express HTT throughout the CNS carries a UAS fused to a polyglutamine-containing domain of the human HTT exon 1 gene. The nonpathogenic, control flies have 20 repeats of CAG/ polyQ (UAS-HTT-exon1-Q20), while the mutant flies carry 93 polyglutatmine repeats (UAS-HTT-exon-1-Q93) (Steffan, 2001). Since the UAS-GAL4 system is used to express HTT, the transgenic flies can be maintained as homozygous stocks. Using the pan-neuronal elav-GAL4 driver, the HD transgenes are expressed in all neurons from fly embryogenesis onward. In the pathologic HD fly, eclosion rates were reduced by ~70%; externally normal adults can be observed trapped in their pupal case (McLear et al., 2008; Wolfgang et al., 2005). Eclosion hormone is released from the brain at a precise time and circulates into the periphery to act on various systems to elicit this complex behavior (Horodyski et al., 1993). Reduced eclosion rates represent incomplete penetrance of the pathology, which can be corrected by maintaining the flies at a lower temperature. The variation in temperature responses may be an effect of the GAL4 driver. Overall, disrupted eclosion may be a cell-autonomous affect of HTT in neurons or muscle cells. Alternatively, it could be due to a cell non-autonomous effect that may influence hormone levels in cells that are required for escape from the pupal case. It would be interesting to explore these possibilities. In addition to reduced eclosion rates, adult lifespan was shortened to ~6 days, and neurodeneration was observed by progressive loss of the photoreceptor cells of the eye in the HD fly (Steffan et al., 2001). Photoreceptor neurodegeneration has been demonstrated as an easily quantifiable marker for widespread neuronal loss in the brain in this HD model (Agrawal et al., 2005). HTT aggregates were observed in the optic lobe neurons of newly eclosed flies (Wolfgang et al., 2005). These assays, therefore, allow researchers to examine representative, key features of human HD pathology including, early death, HTT aggregation and neurodegeneration. Importantly, the HD flies and quantitative assays provide researchers a model in which to investigate potential therapeutics.

6.1.3-- Intrabody allows partial correction of the HD fly phenotype

This HD fly model is ideal for the initial in vivo studies of therapeutic effects of intrabodies. ScFv-C4 gene was injected into the fly embryo to be expressed under the UAS-GAL4 system. Co-expression was achieved by crossing the elav-GAL4 fly to the transgenic fly harboring both the UAS-ScFv-C4 and UAS-HTT exon 1 in the CNS using the UAS-GAL4 system. C4 increased eclosion rates from 23% up to 100%, significantly extended adult life span, and slowed both neurodegeneration and aggregation (Wolfgang et al., 2005). However, rescue of HD pathology was incomplete even with increased expression of ScFv-C4 intrabody, as flies died prematurely, and adult aggregation and neurodegeneration were not halted. We next tested the VL12.3 intrabody, which looked promising in cell culture. However, eclosion rates of HD flies expressing VL12.3 were only improved to 73% compared to nearly 100% in the HD, ScFv-C4 flies and adult survival was not significantly improved. Furthermore, attempts to increase expression of VL12.3 in the presence of HTT exon 1 proved to be toxic.

6.1.4-- Intrabody combinational approaches tested using HD flies

The UPS has been targeted to clear HTT intracellularly. Thus, enhancement of intrabody protection has been explored in combinational approaches via genetically changing the levels of Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), a chaperone protein that is upregulated to aid in refolding proteins and shuttling proteins to the proteasome. Importantly, HSP70 was previously found to accumulate with HTT aggregates (Agashe and Hartl, 2000). Flies were generated that expressed elevated or reduced levels of HSP70 alone and in combination with ScFv-C4 (McLear et al., 2008). Overall, increased HSP70 levels improved survival more than intrabody alone while reducing HSP70 levels was detrimental. Concomitant expression of HSP70 and ScFv-C4 showed a modest, yet significant, additive effect in increasing survival of adult HD flies. However, intrabody alone remained more effective at slowing neurodegeneration and aggregate formation. Interestingly, HSP70 alone had no effect on HTT aggregation (McLear et al., 2008). The absence of a robust additive effect of HSP70 with intrabody suggests that HSP70 and intrabody most likely work on separate pathways; however, combinational approaches that improve lifespan and neutralize HTT protein remain attractive strategies.

A ScFv-C4-HSP70 fusion intrabody was also constructed and tested in flies. Several transgenic lines expressed the fusion intrabody using the UAS-GAL4 system. However, when the fusion intrabody transgenic line was crossed to the HD pathogenic flies, soluble protein was not observed by immunoblotting. Furthermore, HD flies expressing the fusion intrabody showed a decreased lifespan compared to HD flies alone. This fusion intrabody was therefore not further pursued as a therapeutic approach in flies. However, it is interesting to note that intrabody stability and/or solubility may have been compromised leading to a more severe phenotype.

In the same HD Drosophila model, cystamine, a competitive inhibitor of transglutaminase reduced neurodegeneration (Agrawal et al., 2005). Cystamine is proposed to interfere with glutamine crosslinking and reduce HTT aggregation (Dedeoglu et al., 2002; Kahlem et al., 1996). In a combinational approach, HD flies expressing intrabody were treated with cystamine either throughout their lifespan (raised as larvae) or as adults only. When fed to adults, 100 □M cystamine (a medium dose), in combination with intrabody treatment, rescued photoreceptors by 66% compared to the HD flies. This was more protective than either treatment alone, but did not improve lifespan. In contrast, presymptomatic treatment of the flies in combination with intrabody improved lifespan compared to either alone. However, we could not measure an increase in neuronal survival (Bortvedt et al., 2010). Huntingtin aggregation was not measured in theses assays; therefore a correlation cannot be made regarding neurodegeneration vs. lifespan with aggregation.

6.2 Intrabody correction of HD mouse model phenotypes

6.2.1—HD mouse models

As an autosomal dominant disease with ubiquitous gene expression in humans, but generally with onset in adults, or at least after the age of 2, HD has forced mouse model developers to make choices to recapitulate different aspects of disease in the relatively short-lived mouse. The first set of mouse models, still in very active use, used an HTT exon 1 fragment from an HD juvenile patient, with approximately one KB of the native promoter region, to create several lines of R6 transgenic mice (Mangiarini et al., 1996). Most show neuropathology within weeks of birth, which may be due to the fact that the HTT protein has already undergone proteolysis to a toxic N-terminal fragment. These mouse lines had random insertions, and variable CAG repeat numbers, since the insert was an unstable pure CAG repeat. HDR6/2 mice, with 165Q, show motor abnormalities by 6 weeks, very early accumulation of Neuronal nuclear inclusions in the striatum and other brain regions, and death by 12–16 weeks. This early aggregate formation, and aggressive disease timecourse, makes prevention of the process challenging. The HDR6/1, Q120, mice have a later age of onset for both histopathological and neurological symptoms, and may be more amenable to intrabody intervention, while maintaining the advantage of the physiological promoter. There is also a transgenic N-terminal HD fragment model, N171-82Q, which is driven by a prion promoter (Schilling et al., 1999), that shows a robust phenotype, with supraphysiological transgene expression, and significant aggregation that starts late enough to be corrected with adult treatment. To more fully recapitulate the natural disease, full-length models have also been developed. Those that are based on the human gene use yeast or bacterial artificial chromosomes; YAC128 and BAC97 are the most useful to date (Gray et al., 2008; Slow et al., 2003). Appearance of inclusions tends to be most reliable after about one year, although other aspects of the phenotype appear earlier. A full summary of these and other models is in Crook and Housman (Crook and Housman, 2011).

6.2.2-- scFv-C4

This scFv intrabody targeted to HTT AA1–17, when delivered neurosurgically, is sufficient to achieve cellular correction of the aggregation phenotype,when the current best vector and striatal delivery is used in the B6-HDR6/1 fragment mouse model. To assess long-term efficacy and safety issues in vivo of scFv-C4, we used adenoassociated viral vectors (AAV2/1) to deliver scFv-C4 intrabody genes into the striatum of inbred B6.HDR6/1 mice. Intrastriatal injection of scFv-C4 resulted in a significant reduction in the size and number of HTT aggregates at various stages of the disease (Snyder-Keller et al., 2010). This protective effect diminishes with age beyond 6 months, although it does not disappear entirely (Snyder-Keller et al., 2010). Confocal imaging with an anti-HA antibody, used to identify the presence of intrabody, confirmed that most transduced cells lack HTT aggregates; however, transduction rates were insufficient to provide behavioral correction. Newer delivery vectors, more stable and bifunctional fusion constructs, and combinatorial therapies are being used to follow up on these promising data.

6.2.3-- V L-Happ1

Southwell et al tested the therapeutic efficacy of Happ1 using an acute unilateral lentiviral model; and R6/2, N171-82Q, YAC128, and BACHD transgenic HD mouse lines, with intrastriatal AAV delivery of intrabody genes (Southwell et al., 2009). In all five mouse models, intrastriatal AAV delivery of Happ1 corrected different aspects of the disease phenotype in a variety of motor and cognitive assays, as well as neuropathology (Southwell et al., 2009; Southwell and Patterson, 2011). The N171-82Q model also showed increased body weight and a 30% increased lifespan. Correction is still incomplete, but the direction is promising.

6.2.4-- scFv-EM48

mEM48 is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes an epitope in the C-terminus of HTT exon 1. Wang et al, converted this monoclonal antibody into an scFv, and subsequently delivered it via adenoviral delivery into the striatum of transgenic N171-82Q HD. scFv-EM48, which only recognizes human mHTT, reduced neuropil aggregate formation, and could alleviate motor deficits of N171-82Q mice across an 8- week duration of experiments (Wang et al., 2008). Longer testing periods, and delivery to other cell types, should be very interesting.

7. Future Directions

In this section, we will briefly consider the steps that still need to be accomplished in order to use intrabodies clinically, as well as broader immunotherapeutic approaches.

7.1 Clinical use and safety

Several aspects of safety considerations for the use of intrabodies have been discussed above. These antibody fragment constructs do not contain the Fc region, which is known to activate microglia, enhancing an inflammatory response that has been associated with neurodegenerative disease progression (Lunnon et al., 2011). Other considerations include off-target effects, which are unlikely from these antibody-based reagents; and total depletion of the wild type form of the misfolding protein, which is also unlikely based on data suggesting selective targeting of fragment (at least for scFv-C4). If the intrabodies require significant chaperone and (re)folding resources from the transduced cells, this is clearly suboptimal under disease stress conditions; further engineering of the intrabodies should be able to reduce this requirement. Toxic side-effects of the delivery methods are a separate category of concern that must be dealt with for a wide range of neurodegenerative disease gene therapies.

Both scFvs and dAb nanobodies are already in human clinical trials for cancer and infectious diseases, although none of these are currently specifically delivered intracellularly, and most are thought to be working as extracellular entities (Aires da Silva et al., 2004; Doorbar and Griffin, 2007; Groot et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2008; Marasco et al., 1998; Mukhtar et al., 2009; Tanaka et al, 2007). The scFvs can be selected from human display libraries, and therefore should not elicit an immune reaction, even with eventual systemic administration. Immunogenicity of the camelid VHH nanobodies also should not be a major problem, since camelid heavy-chain protein scaffolding sequences do not differ substantially from those in humans, and minor changes can further ―humanize‖ these proteins. A recent list of VHH human clinical applications includes three Phase 2 (one completed and successful), and four Phase 1 trials. (http://www.ablynx.com/en/research-development/pipeline/) Of particular interest is a novel anti-CXCR4, ALX-0651, which is a biparatopic Nanobody, targeting two different epitopes on the same protein. A similar approach to HTT would allow us to pair an anti-N-term AA1–17 with an anti-polyPro, although we might choose to keep them unlinked if preliminary testing reveals that a linked construct pulls monomers together. There are several combinatorial approaches that also hold promise, although these may present even more stringent regulatory hurdles than the use of single reagents.

7.2 Combinatorial therapies

Even with intrabodies that have been selected against specific protein targets, and delivered as genes or proteins, the single targets will correct only part of the pathogenic picture. The treatment of chronic diseases always involves multiple therapeutic approaches used in combination. Knowledge of the mechanism of action of the intrabody-based therapeutics should enable us to design effective combinatorial regimens that complement the intrabody correction. Small molecules are especially appealing in this regard, since they can show widespread distribution, both within and outside the CNS. Drosophila HD intrabody models seem particularly well-suited for preliminary screening of complementary drugs. The example of cystamine is discussed above (Bortvedt et al., 2010).

Based on a protective response in HD fly models (McLear et al, unpublished), we also tested nicotinamide in HD transgenic mice. Nicotinamide improves motor deficits and upregulates PGC-1alpha and BDNF gene expression in R6/1 mice, apparently via a pathway that may be well downstream of the intrabody (Hathorn et al., 2011). The doses used were not toxic, although they did not appear to confer long-term neuroprotection. However, this direction in combinatorial anti-HD therapy could allow brain regions and peripheral tissues that are not strongly affected by mHTT to survive stress for a significant length of time, while the intrabody acts directly to protect neurons in the most affected brain regions.

An approach that may be more related to the primary corrective mechanism of the engineered antibodies, but that can potentially offer more widespread peripheral, if lower-level, protection is active vaccination with either N-terminal HTT peptides, or mutant HTT fragments. The background work is the most clinically advanced in AD, which has seen both active and passive (monoclonal antibody infusion) therapies in clinical trials involving thousands of patients worldwide. Two comprehensive recent 2010 reviews (Solomon and Frenkel; Wisniewski and Sigurdsson, 2010) cover this field. There have also been setbacks, specifically when the immune response appeared to engender a deleterious inflammatory reaction in the brain. However, newer formulations have succeeded in reducing the plaque burden in the modest number of patients who have come to autopsy. The other diseases of accumulating, misfolding proteins have been studies mainly with mouse models. The most relevant for HD (also AD-related, reviewed in above) is the immunization with phosphorylated Tau. In these studies, antibodies from a systemic immunization have migrated to the brain, and can be found intracellularly in affected neurons, with clearance of tangles, and behavioral improvements. In Miller et al, 2003 (Miller et al., 2003), we were able to show that a manual intradermal plasmid immunization with mutant HTT exon1 was able to rescue pancreatic beta cells, and counteract the glucose intolerance phenotype in R6/2 mice. Responses to concurrent peptide immunizations were significantly less protective. We chose to test plasmid immunization, in order to mimic the immune response to a viral infection. This would both increase the probability of targeting of an intracellular antigen, and allow presentation of a physiologically-misfolded peptide to the immune system. Although we were unable to measure an improved neurological phenotype with the limited number of animals and assays available at that time, the study offers a strong rationale for a more comprensive test of a plasmid immunization approach. Again, combining this modest level of protection outside the brain with direct intracranial intrabody treatments may be very beneficial.

7.3 Concluding remarks

In the 13 years since we initially started adapting antibody engineering technology to neurodegenerative diseases, there have been a large number of significant advances in our understanding of the target proteins, as well in both basic concepts and ―tricks of the trade‖ for antibody engineering. Gene delivery has also made progress, although it could still be considered the weak link in the chain leading to the application of intrabodies to human neurological therapeutics. As the number of human gene therapy trials in this area increases, new delivery options should be emerging. Protein delivery would appear to be further in the future for intracranial and intracellular targets, although cellular factories that release bispecific penetrating antibodies following ex vivo transduction and brain implantation have appeal. Combining further engineering of the antibody constructs with stronger delivery methods should allow intrabodies to become a viable arm of multiplexed therapies for the increasingly wide range of neurodegenerative and other diseases that are recognized as being triggered by toxic proteins

Figure 3.

The binding domains for the published anti-HTT intrabodies.

Highlights.

Intracellular antibody fragments (intrabodies) can be selected against toxic proteins

Intrabodies offer a targeted proteomic approach to polyglutamine toxicity

Phenotypic correction has been shown in Huntington’s cell and animal models

Antibody engineering allows bifunctionality, and enhanced stability and efficacy

HD intrabody studies validate this technology for other neurodegenerative diseases

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Messer lab for helpful discussions of the manuscript, especially Shubhada Joshi for modifications of Fig. 1. Work in the Messer lab was supported in part by grants from NIH/NINDS NS053912 and NS061257, and NSF REU #DBI1062963, .High Q Foundation, Hereditary Disease Foundation / Cure HD Initiative, and Huntington’s Disease Society of America.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- dAbs

Domain antibodies

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- HSC70

heat shock cognate protein 70

- HSP70

heat shock protein 70

- HTT

huntingtin protein

- mHTT

mutant huntingtin protein

- PEST

Proline (P), Glutamic Acid (E), Serine (S), and Threonine (T)

- PolyP

polyproline

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- QBP

polyglutamine binding peptides

- scFv

single-chain Fv

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

- VH

variable heavy; single-domain

- VL

variable light chain; single domain

- VHH

small heavy-chain-only Camelidae antibody fragments

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agashe VR, Hartl FU. Roles of molecular chaperones in cytoplasmic protein folding. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:15–25. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N, Pallos J, Slepko N, Apostol BL, Bodai L, Chang LW, Chiang AS, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. Identification of combinatorial drug regimens for treatment of Huntington's disease using Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3777–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500055102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken CT, Steffan JS, Guerrero CM, Khashwji H, Lukacsovich T, Simmons D, Purcell JM, Menhaji K, Zhu YZ, Green K, Laferla F, Huang L, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. Phosphorylation of threonine 3: implications for Huntingtin aggregation and neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29427–29436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aires da Silva F, Santa-Marta M, Freitas-Vieira A, Mascarenhas P, Barahona I, Moniz-Pereira J, Gabuzda D, Goncalves J. Camelized rabbit-derived VH single-domain intrabodies against Vif strongly neutralize HIV-1 infectivity. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allay JA, Sleep S, Long S, Tillman DM, Clark R, Carney G, Fagone P, McIntosh JH, Nienhuis AW, Davidoff AM, Nathwani AC, Gray JT. Good manufacturing practice production of self-complementary serotype 8 adeno-associated viral vector for a hemophilia B clinical trial. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:595–604. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]