Abstract

Participation of African Americans in research trials is low. Understanding the perspectives of African American patients toward participation in clinical trials is essential to understanding the disparities in participation rates compared with whites. A qualitative study was conducted to discover attitudes of the African American community regarding willingness to participate in breast cancer screening and randomized clinical trials. Six focus groups consisting of 8 to 11 African American women (N = 58), aged 30 to 65, were recruited from local churches. Focus group sessions involved a 2-hour audiotaped discussion facilitated by 2 moderators. A breast cancer randomized clinical trial involving an experimental breast cancer treatment was discussed to identify the issues related to willingness to participate in such research studies. Six themes surrounding willingness to participate in randomized clinical trials were identified: (1) Significance of the research topic to the individual and/or community; (2) level of trust in the system; (3) understanding of the elements of the trial; (4) preference for “natural treatments” or “religious intervention” over medical care; (5) cost-benefit analysis of incentives and barriers; and (6) openness to risk versus a preference for proven treatments. The majority (80%) expressed willingness or open-mindedness to the idea of participating in the hypothetical trial. Lessons learned from this study support the selection of a culturally diverse research staff and can guide the development of research protocols, recruitment efforts, and clinical procedures that are culturally sensitive and relevant.

Keywords: African American, Breast cancer, Clinical trials, Focus group study

Breast cancer mortality rates remain highest among African American women.1–4 Recent reports have shown racial and ethnic disparities in provisions of healthcare,5 including racial inequities in cancer treatment.6 It has been suggested that these disparities could be reduced significantly with high quality treatment.7,8

Clinical trials offer innovative treatment which can potentially improve clinical outcomes.9 Recent attention to reducing disparities in treatment options has resulted in efforts to increase the enrollment of racial groups in clinical trials.10,11 In support, the government requires investigators to provide evidence of ethnically diverse recruitment efforts.12,13 Given disparities in cancer mortality and the valuable data obtained from cancer treatment trials, it is imperative that African Americans have the opportunity to participate in these trials.

Recruiting women to participate in research has been challenging, regardless of race. Recent studies report a response rate in phase I trials of less than 5%,14 and only 3% participation in clinical trials among breast cancer patients.15,16 Representation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials has been low.10,15,17,18 Lack of participation by African Americans in randomized clinical trials has been attributed to discrimination and mistrust of the healthcare system.19,20 Reactions to the 1932 Tuskegee experiment, for example, continue to have a profound negative impact on recruiting African Americans for clinical trials.21–23

Some researchers have found that minority patients are willing to participate in clinical trials, yet find that these patients have barriers which hinder their access to trials,24,25 whereas other studies have suggested that minority women are unwilling to participate in research studies.26–35 Therefore, further exploration of the potential barriers to participation in clinical trials is essential to increase participation and retention rates, and ultimately, to reduce disparities in quality healthcare and treatment options provided to African American women. The present focus group study aimed to gain a better understanding of the issues surrounding African American women’s willingness, or unwillingness, to participate in randomized clinical trials.

Methods

Participants

Six focus groups were conducted with 8 to 11 African American female participants in each (N = 58 total) during the months of February, March, and April of 2003. Human Subjects approval was obtained from the University of Washington. Women were recruited from churches serving the African American community in King County, Washington. Approval from the church pastor or Health Ministry Department Head was obtained by an African American investigator active in the community. Flyers were distributed to parishioners, inviting them to contact our research office if they were interested in participating. Women were screened over the telephone, and met eligibility requirements if they were aged 30 to 65, a non–health professional, and had never been diagnosed with breast cancer. Reminder calls were made 1 to 3 days before the focus group, resulting in 100% participation. Groups were held in conveniently located local African American church facilities (n = 3) or community facilities (n = 3). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Focus Group Method and Data Collection

Focus groups allow for more extensive exploration of a research topic. Participants can collectively present different perspectives, generate ideas, and compare their ideas with those of others.36,37 Our focus group sessions followed a semistructured guide38 to allow facilitators to follow certain topics and still open new lines of inquiry when appropriate. The guide was beta-tested by a convenience sample of 2 groups of employees at the sponsoring medical center (n = 16).

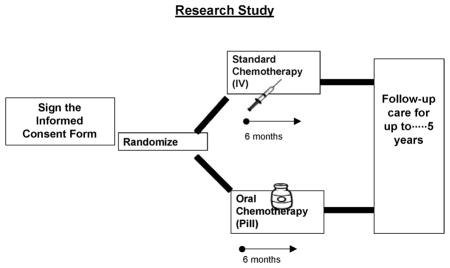

The focus group guide consisted of questions about breast cancer screening and participation in randomized clinical trials (Appendix A). The guide also included a hypothetical clinical trial to generate discussion about willingness to participate. The hypothetical trial was a simplified phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy (oral vs. parenteral) currently being conducted throughout the United States39 (Appendix B). Visual aids explained the trial (Appendix C), and a handout depicting the randomization process was distributed (Appendix D). The audiotaped groups were co-facilitated by the Focus Group Coordinator and an African American Patient Care Coordinator. Women completed a brief demographic survey and were offered a $50 payment for their participation.

Coding and Analysis

Survey responses were coded and entered into SPSS V. 11.0 for Windows for descriptive analysis. Transcribed audiotapes were analyzed using QSR NUDIST 4.0 (Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty. Ltd., Victoria, Australia), a software commonly used by qualitative researchers to document the development of codes and the formulation of theoretical ideas.38 Three investigators independently read transcripts to identify major themes and develop a coding scheme. Versions of themes were merged and refined until a consensus was reached and a template of open codes was constructed for analysis. The second co-facilitator reviewed the analytic tree for accuracy.

Results

Study Population

Fifty-eight African American women attended 6 focus groups (Table 1). All 58 women expressed that breast cancer research is a useful endeavor, should continue until a cure is found, should include participants from all ethnic backgrounds, and could serve as an opportunity to “get the word out” and educate all communities. When asked whether they would participate in the hypothetical trial, the groups were mixed with approximately 11 of 58 women disinterested, 35 women interested, and the remaining 12 women either undecided or hesitant. Participants expressed that the likelihood of their personal participation was greater than that of their community, especially compared with the “older generation.”

Table 1.

Personal and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 58)

| Characteristic | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 46 (range 30 to 65) |

| Country of birth | |

| United States | 58 (100) |

| Region of country at birth | |

| West Coast | 22 (40) |

| East Coast | 5 (9) |

| South | 14 (24) |

| Midwest/Central | 7 (12) |

| No response | 6 (10%) |

| Employment | |

| No | 25 (43) |

| Part-time | 7 (12) |

| Full-time | 24 (41) |

| No response | 2 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 29 (50) |

| Married | 18 (18) |

| Widowed | 3 (5) |

| Divorced | 8 (14) |

| No. of children | |

| None | 12 (21) |

| 1 or more (range = 1–9, mean = 2) | 44 (76) |

| No response | 2 (3) |

| Household income | |

| Less than $25,000 | 18 (31) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 23 (40) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 7 (12) |

| $75,000 or more | 5 (9) |

| No response | 5 (9) |

| Family history of breast cancer | |

| No | 24 (41) |

| No, but relatives with other cancers | 6 (10) |

| Yes | 24 (41) |

| Not sure | 3 (5) |

| No response | 1 (2) |

| Previous breast biopsy | |

| No | 49 (85) |

| Yes | 8 (14) |

| No response | 1 (2) |

| Previous breast surgery | |

| No | 50 (86) |

| Yes | 5 (9) |

| No response | 3 (5) |

| Frequency of physician visits | |

| Never/only when sick | 3 (5) |

| Every 2 years | 3 (5) |

| Annually | 37 (64) |

| More than once a year | 13 (22) |

| No response | 2 (3) |

| Frequency of mammograms | |

| Never/only when symptoms | 15 (26) |

| Every 2 years | 9 (16) |

| Annually | 27 (50) |

| More than once a year | 2 (3) |

| No response | 5 (9) |

Six major themes emerged describing participants’ willingness, or unwillingness, to participate in breast cancer research:

1. Significance of the research topic to the individual and/or community

Most participants were willing to participate in breast cancer clinical trials if the research topic was personally meaningful to them. Personal meaning was met if they were personally concerned with the topic due to a family history experience, or if they believed the topic was personally interesting to the African American community. Participants made statements such as “even money wouldn’t bring me to do something I wasn’t interested in.” Twelve individuals had participated in research studies before the focus group on diverse topics (ie, metabolic, psychiatric, and social issues), 11 because the topic personally affected their lives and provided an opportunity to obtain better treatment.

If a loved one had died of the disease after choosing to decline medical treatment, personal meaning seemed to have great significance. Participation in the focus group study gave women an opportunity to control their personal frustration over a hesitating loved one, and “right” something which had gone “wrong.”

A few women attended the focus group because they had heard or read that African American women were dying of breast cancer at a greater rate than other racial groups, and that gave breast cancer research significance for them. One of these women stated, “On the Internet I saw this article about the incidence of breast cancer in black women. That affected my attention and the kind of care we get, the kind of screening we get, and why the numbers are so high opposed to other women. That told me that I need to learn more about this.”

2. Level of trust in the system

Participants expressed an overall distrust by the African American community and a personal difficulty “trusting the system.” Terms such as “guinea pig,” “lab rat,” “the syphilis study,” “Tuskegee,” and “White America” were used several times in all 6 focus groups. Many women expressed suspicion regarding the funding source for research studies, and concern that funding would eventually end for programs which help the African American community. When asked which groups are less willing to participate in research, one woman stated, “Black women are less willing to participate in research. We’re too suspicious and one thing we don’t trust are studies. There’s trickery…Not just Tuskegee, but that was the big one that a lot of people remember.”

Many women expressed mistrust in recruitment and believed that culturally sensitive recruitment efforts could go a long way toward gaining trust among the African American community. These women were comforted by the fact that for the present study they were recruited by an African American woman, and specifically through their churches. One woman stated, “It was presented at church. It was from one of the female ministers in the church, so that gives it legitimacy to me. I didn’t think about it twice.”

3. Understanding the elements of the trial

Participants expressed a need to make an informed choice regarding participation in a research study. Questions were posed by participants in an attempt to understand the elements of a randomized trial, suggesting they needed convincing answers before making a decision (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants’ Questions About Breast Cancer Treatment Clinical Trials

| Study purpose |

| What is the study purpose? |

| Is the purpose to find a cure? |

| Expectations of study participants |

| How long is the study? |

| What would be required of me? |

| Is there a placebo group? |

| Success of the treatment thus far |

| What are the results of previous studies? |

| What are the results from this study thus far? |

| How successful is the treatment? |

| Particulars of previous or current study participants |

| What are the statistics on other patients? |

| Can I talk to previous, or current, participants? |

| What was the outcome for other participants? |

| What are the side effects for other participants? |

| How are phase I and phase II women doing? |

| Removal from trial |

| If the treatment is not working for me, can I pull off the trial? |

| At what point will I know if the treatment is working or not? |

| Safety |

| What are the side effects? |

| Can the treatment be so harsh that you die from it? |

| How long has the treatment been out? |

| Funding |

| Who is the Funding source? |

| Is there a chance that the funding could end half-way through? |

| Support from personal physician |

| Does my doctor recommend that I be involved? |

| Could my doctor interact with study researchers? |

| Will my doctor still be involved in my treatment? |

| Racial representation |

| What part of the world is the study being conducted in? |

| How many African American women are involved? |

| How many women in other racial groups are involved? |

| How many African American women have taken the treatment and survived? |

Approximately 10 minutes was spent in each focus group explaining the hypothetical clinical trial and reviewing user-friendly visual aids to describe the randomization process. Following the explanation of the trial, many women did not understand the concept of randomization, assuming that participating in the research would give them access to the treatment being tested. One woman said: “PARTICIPANT: I might go with the pill.”

For many women, a lack of choice over treatment arms resulted in a loss of interest in trial participation.

4. Preference for “natural treatments” or “religious intervention” over medical care

Women adamantly against participating in the hypothetical trial were typically in favor of “natural” treatments for breast cancer, instead of medical treatments. In one group, half of the members (n = 4) would not consider participating in a clinical trial because they would choose to “go natural.” One participant summed it up by saying, “I’ve seen too many people with cancer and what chemotherapy does. I would take alternative measures that have nothing to do with chemotherapy and radiation.”

The importance of “praying” over medical interventions was frequently mentioned for older generations of African American women. One woman stated, “Especially southern black women raised in churches…God was the healer. They didn’t go to doctors for everything, and grandma had a home remedy that could cook up really quick. And it worked, you know.”

In contrast, women willing to participate had strong beliefs that science saves lives and provides women with options. These women made comments such as “it’s nice to have treatment options,” “we cannot advance without this study,” and “doing something is better than nothing.”

5. Cost-benefit analysis of incentives and barriers

Participants had busy lives, filled with socioeconomic challenges, making any extra responsibilities and inconveniences a barrier. Participants weighed personal costs and benefits of trial participation. This cost-benefit analysis included logistic inconveniences or expenses (ie, transportation, time invested, costs of drugs and medical care, daycare issues, and the interface with work and family). One woman stated, “Time is a big one because we live in a fast-paced world, and now I’m going to get into a year-long research study. That’s just another slice of my time, my pie. I have to really evaluate that, really weigh it out.”

6. Openness to risk versus a preference for proven treatments

Participants varied in their openness to clinical trial participation. Willing women were more adventurous, accepting of risk, and willing to take “leaps of faith” for the chance of a better life or outcome. Unwilling women were more cautious and guarded, risk averse, and more invested in safe, fully informed decisions.

Willing “risk taking” women felt a strong desire to be open to helping toward the goal of science finding cures for illnesses, even if that meant taking a risk, or putting your own life on the line, for the advancement of science. Women made statements such as “life is about taking chances” and “research needs volunteers, not just animals.” One woman stated, “For us to get a cure, we would need volunteers to test it out. It might not work for us, but it might work for the next person. If they just test it on animals we would never know on humans.”

Willing women would take the risk of being randomized into a treatment group that was a standard treatment, in hopes that they would get assigned instead to the experimental treatment, which seemed more hopeful. With respect to our hypothetical clinical trial, many women wanted to participate because the oral chemotherapy seemed a more promising alternative to the parenteral regimen.

Unwilling “risk averse” women had concerns that participating in a clinical trial may be simply too risky. They had concerns about the safety of the experimental treatment, did not want to be randomized and lose their control over treatment choice, and expressed that participants were taking a risk on receiving a weaker or more toxic treatment. They were fearful of taking a medication, which was not FDA approved for the indication, or not yet proven to be safe and effective. One woman stated, “When your life is flashing in front of your face, you’re going to take whatever’s known to work.”

Discussion

Themes from our qualitative work offer insight into African American women’s perspective of cancer research. Our study confirmed barriers described in the literature regarding mistrust, socioeconomic barriers, and heavy reliance on religion and God in the African American community.19,40 Our themes illuminate some of the intricacies regarding these themes, such as women engaging in “cost-benefit analyses” to weigh barriers against benefits, and individual differences on “risk-taking.”

Three surprising findings in our research study include the following, and support our belief that many African American women are willing to participate in breast cancer clinical trials: (1) We experienced a 100% attendance rate of women who were invited to participate in our focus groups, despite the fact that they did consider the focus groups to be “research”; (2) Among participating women, 80% were willing or at least open to the idea of participating in a hypothetical randomized clinical trial involving a breast cancer treatment of oral chemotherapy; and (3) The women chose to participate in our research as they sought information about breast cancer, screening, and treatment. Our intention when designing the focus group study was not to “educate” the participants, and yet they expressed an appreciation for the “educational opportunity.”

Given our findings that the women in our study are open to the idea of participating in randomized clinical trials, some of the difficulty in recruiting these women to participate, and retaining them once they have volunteered, may involve issues of access to medical research in this community. Other researchers have alluded to the idea that “access,” not “willingness,” is where the difficulty lies in recruiting and retaining minority research participants.24,25

Our findings confirm that many African American women remain reluctant to participate in randomized clinical trials. Reasons for unwillingness previously reported as unique to vulnerable women involve issues surrounding safety and historical breaches of research ethics,22,26–28,41 lack of understanding of research,29–32 in addition to literacy and demographic obstacles.33,34,42 The legacy of Tuskegee, for example, continues to have a profound negative impact on the community, as suggested by others.23

Our findings generate several strategies for researchers attempting to recruit African American women into breast cancer clinical trials:

We attribute our success in recruitment and 100% retention of our focus group participants to recruitment by familiar and credible individuals and sponsorship of African American community churches. Strategic planning in recruitment specifically tailored to the African American community has been suggested.11,43–45 Members of the minority community who have participated in clinical trials could serve as credible sources in building trust with the community, and enhancing participation in studies.

Mistrust remains significant in the African American community, and efforts to educate the community about the ethics of modern research may improve participation in clinical trials. There may be a greater need for targeted efforts such as the recently formed Statewide Tuskegee Alliance Coalition.46 The coalition attributes its success in bridging researchers and community members to community involvement in the early phase of the project.

If “access,” not “willingness,” is a major barrier to willingness to become involved in breast cancer clinical trials, researchers and health professionals must be more aware of their own biases and prejudices. As suggested by others,5,47 prejudice can interfere with equal treatment options being offered to minorities. Investigators must reduce the logistic barriers to participation so that minority groups are truly provided access to a study.

Although the women in our study are interested in research, many are still wary of risk. Therefore, low-risk trials (such as the current hypothetical study) may be more appealing to these groups, and a continuous education process within the community, and throughout the course of a research study, is necessary. A recent study highlighted that patients with cancer are not routinely provided with results of trials in which they have participated, however, most participants surveyed do want to know the results of a treatment study,48 suggesting that notification of findings should be considered the ethical norm and could ultimately lead to greater trial participation.

Cultural sensitivity among researchers and health professionals is necessary. Some African American patients do not believe in medical care, and complex research protocols may only add to this mistrust. Investigators should acknowledge historical cases of discriminatory research protocols, explain to patients how the current study has included safeguards against such abuses, and manage any adverse events in a culturally sensitive manner.

Women desired detailed information about the research study to make an informed choice, and there was difficulty understanding the randomization process. The concepts of randomization and patient rights have been documented as difficult for patients to grasp beyond this community as well,49,50 as have communicating prognostics to breast cancer patients regardless of race.51 Additional effort may be needed to fully inform and educate patients about the elements of the clinical trial, and their rights as participants.

The personal meaning of the research study must outweigh the time, money, and logistic hassles involved in their participation. Costs, especially time, are important to patients with multiple barriers to timely healthcare; studies which can mitigate these costs are more likely to be successful at recruitment.

Our study has several limitations. As evident in a recently published study showing church attendance correlates with positive health practices in the African American community,52 our sampling method of targeting the churchgoing community may offer limited generalizability to the entire African American community, especially “non-churchgoers.” A different group of African American women might have produced the same or different themes, although thematic saturation was noted after 4 groups. Additionally, the cohesiveness of the groups of women, having “church-going” in common, may have created an atmosphere where dissenters did not feel comfortable expressing dissenting views.

Our study has implications for clinicians and researchers, reiterating the need to build trust between with the African American and medical community. Our findings show that, for selected research studies and circumstances, members of the African American community are willing, oftentimes enthusiastically, to participate in breast cancer randomized clinical trials. Additionally, members of the African American community seek education and information on health topics which impact their community. Our challenge is to create culturally sensitive approaches and provide enough information about the research study in order to create a trusting environment where potential participants feel well-informed.

Acknowledgments

Funded by a gift from the AVON Foundation.

Appendix A. Focus Group Semistructured Guide for Discussion

“Ice breaker” question

-

1)

I’d like to start off with a discussion of breast cancer screening, which includes mammograms, breast self-exams, and breast examinations by your physicians. I’d like for us to talk about our own personal experiences with breast cancer screening.

Have any of you had experiences had with breast cancer screening (such as mammograms, breast self-exams, or clinical breast exams) which you would be willing to share with the group?

Is screening useful? Why/why not?

Let’s pretend for a moment. Let’s pretend that someone came up to you and said, “I don’t think getting a mammogram is useful; most of us don’t have cancer, and if I do, I’m just going to die anyway so why bother?” How would you react to this person?

How often do you visit your doctor for breast screening?

Do you get screened as frequently as your physician recommends? Why/why not?

How challenging is it for you to visit your doctor for breast screening?

What are the issues which prevent you from visiting your doctor, or getting a mammogram for breast screening?

-

2)

Medical researchers are trying to gain a better understanding of how we can treat breast cancer once women are diagnosed with the disease. [Describe the oral vs. IV chemotherapy trial, utilizing handout and flowchart].

Let’s pretend that you or a close friend or family member had breast cancer, and your physician recommended chemotherapy to treat the cancer. Your physician also asked you to consider participating in this research study, as a way to effectively treat your cancer, and help other breast cancer patients in the future. Your physician tells you that s/he thinks both types of treatment, either by injection or by mouth are effective, and safe, but that we don’t know which is most effective, and we don’t know which gives patients a better quality of life, which is why there is this ongoing study. What would you say? Would you be willing to participate, or recommend that someone you cared about participate?

How would you feel about your decision to participate/not participate?

Would you feel that this research study is useful?

Would this study be useful for the women participating or for women in the future?

Would you feel that this research study is safe?

Let’s pretend again for a moment. You have a friend with breast cancer who was asked to participate in a study, and chose not to participate. What would you say to that person?

Has breast cancer treatment gotten better because of research studies?

Should we continue doing breast cancer research?

Has anyone in the group ever participated in a research study? OR do any of you know someone who has participated in a research study?

Would any of you be willing to share these experiences with the group?

(If no one responds, give example of lumpectomy vs. mastectomy studies which have shown treatment options to be equivalent, same survival for patients who get mastectomy, complete removal of the whole breast, compared with partial removal of the breast AND radiation treatments every day of the week for 5–6 weeks)

Are these research studies, which the group has shared, useful?

Are these research studies useful for the individuals who are participating? Why/why not?

Are these research studies useful for groups of people? Why/why not?

Are these research studies safe? Why/why not?

-

3)

If you were asked to participate in a research study trying to understand how to improve the treatment for breast cancer, would you participate? Why/why not?

Which of the following factors would you consider (focus the group with these only if we are seeing little response):

Payment

Pressure to participate/not participate

Convenience of the study

Transportation/daycare issues

Fear

Discomfort or stress

Physical examinations/removal of clothing

Are there any other reasons which would factor into your decision to participate?

-

4)

Medical researchers are required to recruit women of all ages, races, and socioeconomic groups to participate in breast cancer research.

What are your thoughts on this?

Is this a good idea, or a bad idea?

Is this necessary or unnecessary?

Are some women more or less likely to participate?

When you see a flyer asking for volunteers to participate, what do you think?

When you are told about a research study looking for volunteers, what do you think?

Is participation in this group what you imagined as research?

How do the 2 compare, visiting your doctor for health visits and participating in research? Are the barriers the same?

Appendix B. Phase III Randomized Study of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Comprising Standard Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate, and Fluorouracil (CMF) or Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide (AC) Versus Oral Capecitabine in Elderly Women With Operable Adenocarcinoma of the Breast

PATIENT ABSTRACT

Rationale

Drugs used in chemotherapy use different ways to stop tumor cells from dividing so they stop growing or die. Combining more than one drug and giving them in different ways after surgery may kill more tumor cells. It is not yet known which chemotherapy regimen is more effective in treating older women with breast cancer.

Purpose

Randomized phase III trial to compare the effectiveness of different chemotherapy regimens in treating older women who have undergone surgery for breast cancer.

Eligibility

At least 65 years old

Must have undergone surgery for breast cancer within the past 12 weeks

No previous chemotherapy for breast cancer

Treatment Intervention

Patients will be randomly assigned to one of 2 groups. Some patients in group one will receive cyclophosphamide by mouth once a day for 2 weeks. They will also receive infusions of methotrexate and fluorouracil once a week for 2 weeks. Treatment may be repeated every 4 weeks for 6 courses. Other patients in group 1 will receive infusions of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks for 4 courses. Patients in group 2 will receive capecitabine by mouth twice a day for 2 weeks. Treatment may be repeated every 3 weeks for 6 courses. Within 4 to 6 weeks after treatment, some patients in both groups may undergo radiation therapy. Some patients may receive tamoxifen by mouth or an aromatase inhibitor once a day for up to 5 years. Quality of life will be assessed periodically. All patients will be evaluated at 1 month, every 6 months for 2 years, and once a year for 15 years.

Disclaimer

This abstract is intended to give a brief overview of this clinical trial. To help determine whether the trial is appropriate for an individual, selected major eligibility criteria are listed above. To obtain more details related to trial eligibility and the treatment plan, please see the Health Professional abstract of this clinical trial. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI Cancer.gov Website.

Appendix C. Handout of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Clinical Trial

IV Chemotherapy Versus Oral Chemotherapy Treatment for Breast Cancer (Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute)

What’s the Study About?

Compare the effectiveness of standard chemotherapy (given by vein) versus oral chemotherapy toward curing breast cancer and increasing survival in women with breast cancer

Compare the quality of life in patients using the 2 different treatment regimens

Compare the toxicity of these regimens

The overall goal is to find a more convenient treatment that is less toxic

Who is Eligible?

Women

Breast cancer patients

Chemotherapy is recommended to improve chance of cure

Tumor removed (either entire or partial breast)

Otherwise healthy

What are my Benefits?

Treatment is covered

More closely followed up (blood tests, visits with healthcare team)

Extra time, answers to questions from research nurse

Treatment may be less toxic but is an active treatment

Has the advantage of being taken by mouth, not by injection

Does not cause hair loss

What are my Risks?

The less toxic treatment may not be as effective. We know that the oral treatment works very well in women with advanced breast cancer. Experts have agreed it is safe. It is likely to be as effective as standard chemotherapy.

Appendix D. Handout Describing Randomization Process

References

- 1.Simon MS, Severson RK. Racial differences in survival of female breast cancer in the Detroit metropolitan area. Cancer. 1996;77(2):308–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960115)77:2<308::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brawley OW. Some perspective on black-white cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):322–325. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brawley OW. Disaggregating the effects of race and poverty on breast cancer outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):471–473. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghafoor A, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):326–341. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smedley BD, Stith A, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Issued by the Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2106–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkins P, Cooksley CD, Cox JD. Breast cancer. Is ethnicity an independent prognostic factor for survival? Cancer. 1996;78(6):1241–1247. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6<1241::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term?) Evidence for a “trial effect”. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killien M, Bigby JA, Champion V, et al. Involving minority and under-represented women in clinical trials: the National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Women’s Health Gend-Based Med. 2000;9(10):1061–1070. doi: 10.1089/152460900445974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark N, Paskett E, Bell R, et al. Increasing participation of minorities in cancer clinical trials: summary of the “Moving Beyond the Barriers” Conference in North Carolina. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(1):31–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Conference ed. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman LS, Simon R, Foulkes MA, et al. Inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials and the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993V the perspective of NIH clinical trialists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16(5):277–285. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daugherty CK, Ratain MJ, Minami H, et al. Study of cohort-specific consent and patient control in phase I cancer trials. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(7):2305–2312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher B. On clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(11):1927–1930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.11.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson IM, Coltman CA, Brawley O, Ryan A. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Semin Urol. 1995;13(2):122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chlebowski RT, Butler J, Nelson A, Lillington L. Breast cancer chemoprevention. Tamoxifen: current issues and future perspective. Cancer. 1993;72(3 suppl):1032–1037. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3+<1032::aid-cncr2820721315>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shavers VL, Lynch C, Burmeister LF. Factors that influence African-Americans’ willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer. 2001;91(S1):233–236. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<233::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouad MN, Partridge E, Green BL, et al. Minority recruitment in clinical trials: a conference at Tuskegee, researchers and the community. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 suppl):S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gamble VN. A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(6 suppl):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: considerations for clinical investigation. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317(1):5–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaluzny A, Brawley O, Garson-Angert D, et al. Assuring access to state-of-the-art care for U.S. minority populations: the first 2 years of the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(23):1945–1950. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldige CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):830–835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denholm JT. The Declaration of Helsinki and research in vulnerable populations. Med J Aust. 2000;173(4):223–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuklenk U. Protecting the vulnerable: testing times for clinical research ethics. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):969–977. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daugherty CK, Siegler M, Ratain MJ, Zimmer G. Learning from our patients: one participant’s impact on clinical trial research and informed consent. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(11):892–897. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, Houssami N. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(15):3554–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erlen JA. Clinical research: what do patients understand? Orthop Nurs. 2000;19(2):95–99. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200019020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wager E, Tooley PJ, Emanuel MB, Wood SF. How to do it. Get patients’ consent to enter clinical trials. BMJ. 1995;311(7007):734–737. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7007.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woloshin KK, Ruffin MT, 4th, Gorenflo DW. Patients’ interpretation of qualitative probability statements. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(11):961–966. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.11.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giuliano AR, Mokuau N, Hughes C, et al. Participation of minorities in cancer research: the influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 suppl):S22–S34. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan DL. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan DL, editor. Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerbert B, Caspars N, Bronstone A, Moe J, Abercrombie P. A qualitative analysis of how physicians with expertise in domestic violence approach the identification of victims. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(8):578–584. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-8-199910190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phase III Randomized Study of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Comprising Standard Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate, and Fluorouracil (CMF) or Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide (AC) Versus Oral Capecitabine in Elderly Women With Operable Adenocarcinoma of the Breast. [Accessed February 8, 2006]; current study, available from the National Cancer Institute at: http://www.cancer.gov/search/viewclinicaltrials.aspx?cdrid=68891&version=healthprofessional&protocolsearchid=2092582.

- 40.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(4):248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(3):134–149. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(23):1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberson NL. Clinical Trial Participation. Viewpoints from racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1994;74(9 suppl):2687–2691. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2687::aid-cncr2820741817>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kagawa-Singer M. Improving the validity and generalizability of studies with underserved U.S. populations expanding the research paradigm. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 suppl):S92–S103. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fouad MN, Partridge E, Wynn T, Green BL, Kohler C, Nagy S. Statewide Tuskegee Alliance for clinical trials. A community coalition to enhance minority participation in medical research. Cancer. 2001;19(1 suppl):237–241. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<237::aid-cncr11>3.3.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haynes MA, Smedley BD, editors. The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. Health Sciences Policy Program. Washington DC: The National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Partridge AH, Burstein HJ, Gelman RS, Marcom PK, Winer EP. Do patients participating in clinical trials want to know study results? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(6):491–492. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Featherstone K, Donovan JL. Random allocation or allocation at random? Patients’ perspectives of participation in a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1177–1180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Criscione LG, Sugarman J, Sanders L, Pisetsky DS, St Clair EW. Informed consent in a clinical trial of a novel treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(3):361–367. doi: 10.1002/art.11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lobb EA, Butow PN, Kenny DT, Tattersall MH. Communicating prognosis in early breast cancer: do women understand the language used. Med J Aust. 1999;171(6):290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Felix Aaron K, Levine D, Burstin HR. African American church participation and health care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):908–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]