Abstract

Scaffolding proteins such as SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 (“AKAP12”) are thought to control oncogenic signaling pathways by regulating key mediators in a spatiotemporal manner. The downregulation of AKAP12 in many human cancers, often associated with promoter hypermethylation, or the loss of its locus at 6q24-25.2, correlates with progression to malignancy and metastasis. The forced re-expression of AKAP12 in cancer cell lines suppresses in vitro parameters of oncogenic growth, invasiveness and cell motility through its ability to scaffold protein kinase C (PKC), F-actin, cyclins, Src and phosphoinositides, and possibly through additional scaffolding domains for PKA, calmodulin, β1,4-galactosyltransferase-polypeptide-1, β2-adrenergic receptors and cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4D. Moreover, AKAP12 re-expression in tumor models results in metastasis suppression through the inhibition of Src-regulated, VEGF-mediated neovascularization at distal sites. The current review will describe the emerging understanding of how AKAP12 regulates cellular senescence and oncogenic progression at the level of tumor cells and tumor-associated microenvironment via its multiple scaffolding functions.

Keywords: SSeCKS/AKAP12, metastasis, neovascularization, microenvironment, Src, PKC, PKA, cyclin

SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 (“AKAP12”) was identified in the mid-90s by four labs independently screening for novel autoantigens in myasthenia gravis, antagonists of Src-induced oncogenic transformation, phosphatidylserine-dependent binding partners of protein kinase C (PKC), and binding partners of PKA [1]. Besides its activity as a tumor- and metastasis-suppressor, which is the focus of this review, there is clear evidence that AKAP12 also facilitates resensitization of β2-adrenergic receptors, regulates neuronal cell injury, helps establish the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers, and contributes to long-term memory- all of which are reviewed elsewhere [2, 3, 4].

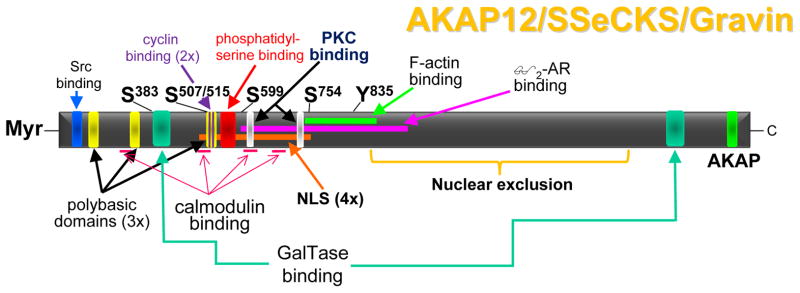

AKAP12 was originally identified as a minor autoantigen, Gravin [5], correlating with poor prognosis in myasthenia gravis [6], and then shown to be orthologous to a rodent protein, SSeCKS (pronounced essex), a major PKC substrate and binding protein whose expression is downregulated in Src- and Ras-transformed cells [7, 8]. These orthologues were subsequently named AKAP250, and now AKAP12 (for A kinase anchoring protein 12), based on their ability to bind RII isoforms of PKA [9]. A current view is that AKAP12 functions as a scaffolding protein, which controls mitogenic signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling by binding key signaling mediators such as PKC, PKA, calmodulin, F-actin, cyclins, Src and phospholipids in a spatiotemporal manner [1] (Fig. 1). AKAP12 also fulfills other typical scaffolding functions required to coordinate signal transduction pathways [10, 11]. For example, AKAP12 crosslinks several cellular compartments, namely, the actin cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane, thereby facilitating signal transfer from the cell surface to cytoplasmic and even perinuclear complexes. This is mediated by an F-actin-binding domain [12], and by N-terminal myristylation [7] and phospholipid binding domains [13]. AKAP12 translocates to new cellular compartments after mitogenic stimulation (from the plasma membrane to the perinucleus [7]), thereby affecting signaling by transporting bound proteins to sites of action or inaction. AKAP12 multimerizes as a homomultimer or as a heteromultimer with other scaffolding proteins such as AKAP5, a function thought to amplify scaffolding activity at specific cellular sites [14, 15]. Finally, AKAP12 exhibits differential scaffolding activity during cell cycle progression, tracking with changes in its own phosphorylation level. Specifically, mitogen-induced serine phosphorylation of AKAP12 in or near scaffolding sites for PKC or cyclins correlates with decreased binding activity, resulting in increased PKC kinase activity and PKC-induced cytoskeletal remodeling, and in increased nuclear translocation of cyclin D [16, 12, 17]. The FAK-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of AKAP12 induced by EGF antagonizes its binding to F-actin, correlating with cytoskeletal remodeling and increased cell motility [12].

Figure 1. AKAP12 scaffolding domains.

Binding domains on AKAP12 are shown for Src, cyclins (2 sites), calmodulin (4 sites), GalTase (2 sites), phosphatidylserine, PKC (2 sites), F-actin, β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR), and RII-PKA (AKAP). Additionally, AKAP12 encodes three polybasic domains that facilitate binding to phosphoinositols, four SV40-type nuclear localization signals (NLS), and a domain that facilitates nuclear exclusion. Four major PKC phosphorylation sites as well as one major tyrosine phosphorylation site are shown. The αAKAP12 isoform is post-translationally myristoylated (Myr) at its N-terminus.

All vertebrate species analyzed including fish (Danio, Tetraodon and Fugu) have AKAP12 orthologs sharing >40% homology at the protein level, however invertebrates (e.g., insects, fungi, or worms) lack credible orthologs. Vertebrates encode a single AKAP12 protein family, and although mice deficient in AKAP12 develop normally [18], albeit with minor defects reflecting pre-cancerous conditions (see below), there is new evidence that AKAP12 deficiency in Danio results in defects to vascular integrity [19].

Multiple lines of evidence bolster the concept that AKAP12 functions as a suppressor of oncogenesis. In brief, these include i) mapping of human AKAP12 to 6q24-25.2, a deletion hotspot in advanced prostate, breast, and ovarian cancer [20], ii) downregulation of AKAP12 by specific oncogenes, in cancer cell lines and human cancer tissues compared to normal controls, iii) upregulation of AKAP12 by treatments such as retinoids that cause cancer cell growth arrest or differentiation, iv) suppression of oncogenic growth in vitro and in vivo, especially metastasis formation, following the forced re-expression of AKAP12, v) induction of a tumor- or metastasis-prone condition in mice lacking AKAP12.

AKAP12 downregulation by oncogenes and in cancer

An early suspicion of potential cancer suppressive activity for AKAP12 was based on its downregulation in fibroblasts and epithelial cells transformed with specific, but not all oncogenes [1], strongly suggesting that AKAP12 antagonizes specific oncogenic pathways. For example, AKAP12 is downregulated by oncogenic Src, Ras, Myc, Jun, Fos, Wnt1 and Dnmt1, but not by Raf, Mos or Neu. AKAP12 levels also track with transformation status, i.e.- they are restored in non-oncogenic revertants and then decrease in retransformants exhibiting anchorage-independent growth [21]. Recent data indicate that Akap12-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF) are prone to oncogenic transformation (anchorage-independent growth) after expression of only a single oncogene [22], strengthening the notion that loss of the AKAP12 tumor suppressor function serves as one of the two required genetic events to drive oncogenic progression [23].

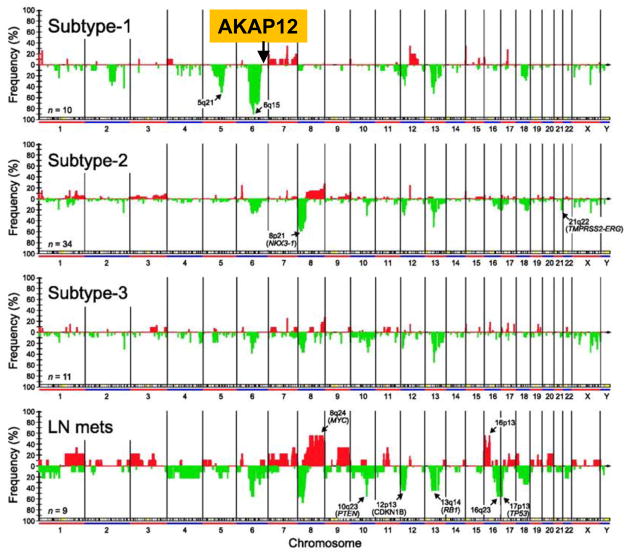

Scores of differential gene expression and copy number variation (CNV) studies demonstrate AKAP12 downregulation in many cancer types in human tumors and cancer cell lines (reviewed in [1]). Importantly, there is a building literature identifying decreased AKAP12 transcript or gene copy levels in metastases compared to matched primary-site colon, prostate, breast or endocrine cancers, or as a predictive marker for bladder and pancreatic cancer metastasis (reviewed in [1]). For example, loss of AKAP12 staining correlates strongly with Gleason sum >6 ([24], Ray M, Zheng S, Nochajski P, Davis W, Mohler JL, Marshall J, Gelman IH. Loss of SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 expression in prostate cancer tissues correlates with disease progression, submitted for publication). However, 40% of more aggressive AKAP12-deficient lesions (Gleason sum 7 to 10) [24] also exhibited gene deletion, as determined by laser capture microdissection followed by PCR analysis using AKAP12 and GAPDH control primers (I.H. Gelman, unpublished data). The correlation of AKAP12 gene loss to prostate cancer metastasis was demonstrated by Lapointe et al. [25], who showed that whereas three CNV subtypes of primary prostate cancers show deletions in the 6q13-22 region, lymph node metastases exhibit an additional deletion of the AKAP12 locus at 6q24-25.2 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Deletion of AKAP12 chromosomal locus associated with lymph node metastasis in prostate cancer.

CNV analysis of primary prostate cancers vs. lymph node metastases (“LN mets”) by Lapointe et al. [25] identifies deletions in the 6q13-22 region in 30–90% of cases, depending on CNV subtype. In contrast, roughly 30% of LN mets exhibit deletions of the AKAP12 locus at 6q24-25.2 [24] (Reprinted by permission from the American Association for Cancer Research).

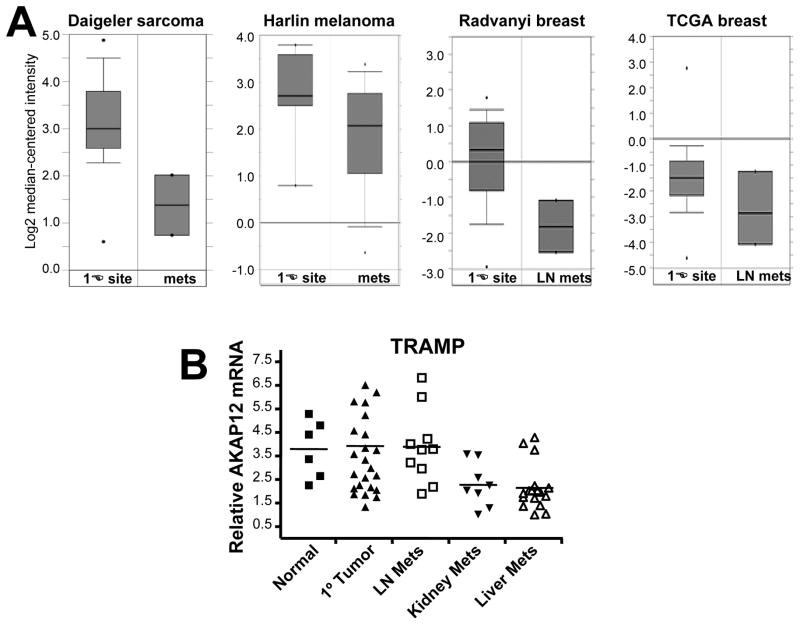

Validated losses of AKAP12 expression (>5-fold over normal tissue controls) have been reported in human and rat prostate cancer cell lines, pulmonary adenocarcinomas, leiomymoma, chronic and acute myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, gastric cancer, non-small cell lung carcinoma, osteosarcomas, melanomas, retinoblastomas, colon and pancreatic cancer, fibrosarcomas, and squamous cell lung carcinoma (reviewed in [1]). Additional microarray and in silico analyses deposited in Entrez GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), Oncomine (www.oncomine.org), the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project SAGE site (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/SAGE), or The Cancer Genome Atlas site (http://cancergenome.nih.gov) identify AKAP12 downregulation (3- to 10-fold) in breast, prostate, lung, liver, thyroid and ovarian cancers and in gliomas (reviewed in [1]). Importantly, though, AKAP12 loss correlates with increased metastatic potential of human sarcoma, melanoma, endocrine, bladder and breast cancers [1](Fig. 3) and of spontaneous liver and kidney metastases compared to either normal prostates or primary-site prostate cancers in the “TRansgenic Adenocarcinoma Mouse Prostate” model, TRAMP (Fig. 3B) (Shannon, Kinney, Barbara Foster, Irwin Gelman and Adam Karpf, unpublished data).

Figure 3. Transcriptional downregulation of AKAP12 in metastases of human and mouse cancers.

(A) Oncomine studies showing AKAP12 downregulation in metastases of sarcoma, melanoma and breast cancer compared to primary-site tumors [80, 81, 82](cancergenome.nih.gov). (B) AKAP12 downregulation as determined by qRT-PCR in liver and kidney metastases from the TRAMP autochthonous model of prostate cancer.

Recent studies have elucidated several mechanisms by which AKAP12 is transcriptional regulated. In rodents and humans, AKAP12 transcription is driven by three independent promoters, α, β and γ, the latter expressed only in the testes [26]. The α and β promoters, which are equally active in most cells and which are co-downregulated in cancer cells [20], splice to a common long exon, resulting in α- and β-AKAP12 proteins that only differ in their N-terminal 7%. The Src-induced downregulation of both α and β AKAP12 promoters involves cis-acting sequences proximal to the transcription start site that bind USF1, Sp1, Sp3, HDAC1 [27], plus a form of TFII-I that converts to a transcriptional repressor once tyrosine phosphorylated by activated Src [28]. Once downregulated, the AKAP12 promoter undergoes hypermethylation at promoter CpG islands in many cancer types such as colon, gastric, prostate, lung, pancreatic and skin [29–37], although a recent case of AKAP12 silencing in multiple myeloma by changes in histone acetylation has been reported [38].

Given that AKAP12 downregulation might, in itself, represent only a bystander effect, it is important to note that AKAP12 loss is associated with increased cancer susceptibility. For example, AKAP12 silencing via promoter hypermethylation [39, 40] has been shown to function as a neoplastic biomarker in the progression of Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma [41]. AKAP12 loss correlates with increased cancer incidence in breast cancer [42, 43], hepatocellular carcinoma [44] and chronic myeloid leukemia [45], and increased lung metastasis in cases of pancreatic cancer [37].

Upregulation of AKAP12 by antagonists of oncogenic transformation

Additional evidence that strengthens a role for AKAP12 as an oncogenic suppressor stems from its induction by genes or treatments that antagonize oncogenic transformation. In this regard, AKAP12 expression is upregulated in cancer cells by the re-expression of the p53 [46] or p21 [47] tumor suppressors, or by antagonizing STAT3β-dependent oncogenic signaling [48]. Similarly, AKAP12 is upregulated during growth arrest induced by differentiating agents such as retinoids [49, 50] or vitamin D3 [51, 52], or following Smad-4–dependent, TGF-β–induced cell cycle arrest [53], but not by generic growth arrest induced by serum removal [54]. Multiple studies identify AKAP12 as androgen-inducible in primary human prostate epithelial cells or in androgen-dependent cancer lines such as LNCaP [55–57], in contrast to androgen-independent LNCaP lines, which exhibit AKAP12 downregulation [58].

Tumor- and metastasis suppression by AKAP12

An important method in the validation of an oncogenic suppressor is to show that its re-expression decreases specific parameters of primary- and/or metastatic oncogenic growth in vitro and in vivo, and in the case of AKAP12, it can have tumor or metastasis suppressing activity depending on the assay used. For example, AKAP12 re-expression significantly decreased v-Src-, Jun- or Ras-induced in vitro oncogenic growth parameters such as anchorage- and growth factor–independence, focus formation, Matrigel invasiveness, and invadosome formation, concomitant with the induction of cell flattening and the reestablishment of normalized cytoskeletal architecture including F-actin stress fibers flanked with focal adhesion plaques [21, 24, 29, 59–62]. The ability of AKAP12 to inhibit oncogenic motility in vitro, such as invasiveness and chemotaxis, correlates in part with the suppression of MMP-2/9 expression and secretion [60, 63, 62]. This involves disengaging Src from activating downstream RhoGTPase-family- and PKC-Raf/MEK/ERK-mediated pathways controlling MMP expression, cytoskeletal remodeling and invadosome formation. Interestingly, AKAP12 re-expression does not inhibit Src kinase activity in cells, in as much as Src autophosphorylation, total phosphotyrosine substrate levels, and the Src-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of specific downstream signaling or invasion mediators such as Shc or Tks5, respectively, is unaffected by AKAP12 re-expression [60, 63, 21]. In contrast, the loss of invadosome structures and Matrigel invasiveness correlates with an AKAP12-mediated suppression of RhoA and Cdc42 activation levels [60] and serum-induced PKC activation levels [63]. The continued activity of Src and the continued ability for serum-enhanced Src phosphorylation of Shc after AKAP12 re-expression [63] suggests that AKAP12 physically disengages active Src from downstream oncogenic signaling rather than inhibiting its intrinsic kinase activity.

Although it remains unclear how AKAP12 controls Rho GTPase family activity, control of PKC is likely facilitated by a direct scaffolding activity by AKAP12, such that saturated binding inhibits PKC kinase activity [9, 16]. This correlates with increased PKC isozyme activity in AKAP12-null MEF [16]. Interestingly, AKAP12-null MEF fail to exhibit phorbol ester-induced cell shape change, i.e.- actin cytoskeletal remodeling, and the ability of re-expressed AKAP12 to rescue this requires two separate, yet homologous PKC-binding sites in AKAP12 with the motif, EGI/VT/SxWxSFKK/RM/LVTPK/RKK/RxK/RxxxExxxEE/D [16]. This strongly suggests that AKAP12 physically transduces signals to downstream PKC substrates that control the actin cytoskeleton. Consistent with this notion, the ability of AKAP12 to suppress cancer cell invasiveness, chemotaxis and cell survival requires its PKC binding domains [63].

A mechanism by which AKAP12 might disengage active Src from downstream oncogenic signaling is based on the identification of a Src scaffolding domain in AKAP12, homologous to the Src-binding domain in caveolin1, which seems to facilitate increased cell adhesion by AKAP12 by inducing Src translocation from FAK-enriched focal adhesion complexes to lipid rafts. The notion that AKAP12 facilitates Src association with caveolae structures is based on the increased level of AKAP12-induced Y14 phosphorylation of Caveolin-1 (Su et al., manuscript under review), a known Src substrate site [64].

In addition to the correlation between AKAP12 loss and metastasis (above), AKAP12 fulfills the functional definition of an in vivo metastasis suppressor [65]: its re-expression does not significantly affect primary tumor growth yet it suppresses metastasis formation. As will be described below, there is mounting evidence that mice lacking AKAP12 are also metastasis-prone. We initially demonstrated metastasis-suppressing activity in rat MAT-LyLu (MLL) prostate cancer cells: the tetracycline-regulated AKAP12 re-expression had a marginal effect on the growth of primary-site tumors, yet there was a severe reduction in the spontaneous formation of macroscopic pulmonary metastases [24, 66]. AKAP12 neither altered generic cell motility (e.g.- in monolayer wound healing assays) nor the rates at which cells colonized distal sites. Rather the micrometastases produced by the AKAP12-re-expressor MLL cells were avascular and reminiscent of experimental pulmonary micrometastases of Lewis lung carcinoma cells growing in Src-null hosts [67], a defect attributed to a failure to transduce VEGF-mediated recruitment of endothelial cells to the metastasis neovasculature [68, 69]. AKAP12 suppresses VEGF expression in MLL and many other cell types [66, 70–74], and indeed, the finding that the forced re-expression of VEGF in MLL/AKAP12-expressing cells rescues macrometastasis formation strongly argues that AKAP12 suppresses a late stage of metastasis, namely VEGF-induced neovascularization at distal sites. A recent study by Liu et al. [75] confirms the ability of AKAP12 to suppress the in vivo metastatic potential of colon cancer cells.

Loss of AKAP12 leads to a tumor- or metastasis-prone condition

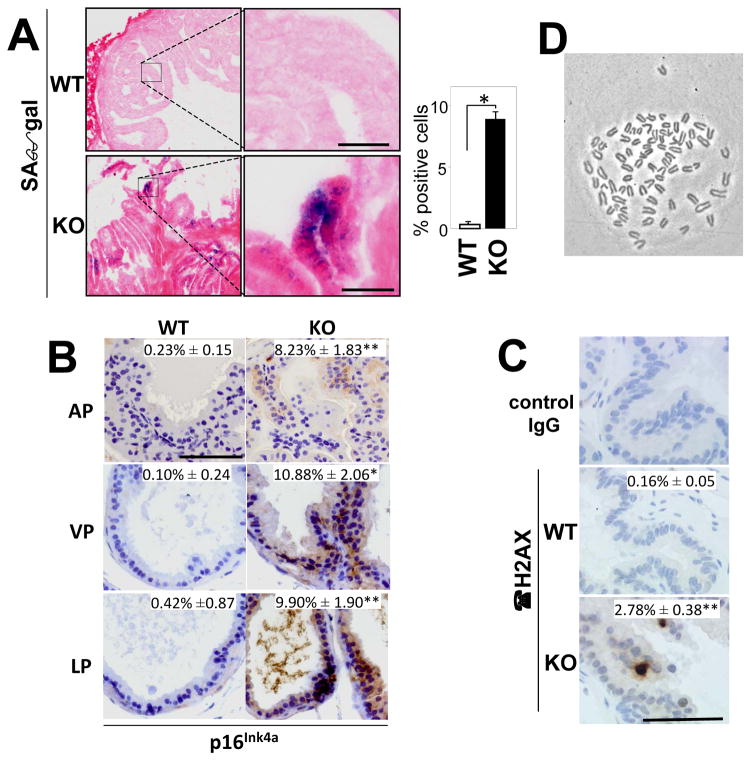

Although AKAP12-null mice have normal longevity, they display hyperplasia in several tissues normally enriched for AKAP12 expression, including the prostate, lung and skin [18, 76]. Moreover, the increase AKAP12-null prostatic cellularity results from higher apoptosis levels and even higher proliferation levels- characteristics of increased senescence, a process thought to represent a protective response to the loss of a oncogenic suppressor function [77]. Indeed, AKAP12-null prostates and MEF display increased markers of senescence, such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase, p16Ink4a and γ-H2AX (Fig. 4A–C), that correlate with increased polyploidy (Fig. 4D) and binucleation [22]. This senescence is Rb-dependent, resulting from hyperactive PKCα and γ due to the loss of AKAP12 scaffolding activity. Importantly, AKAP12 deficiency renders these MEF prone to oncogenic transformation by only one oncogene, such as Src or Ras, in contrast to WT-MEF, which require at least two oncogenes [22]. The notion that AKAP12 deficiency increases oncogenic susceptibility in vivo is borne out by two recent studies. In the first, Akakura et al. [76] demonstrate increased carcinogen-induced papilloma formation and conversion to squamous cell carcinoma in AKAP12-null mice, and although the frequency was low, several treated AKAP12-null mice developed spontaneous spindle cell carcinoma metastases. Interestingly, the increased carcinogenesis in the absence of AKAP12 correlates with induced levels of FAK, a known mediator of skin cancer progression [78]. In the second, AKAP12-null mice exhibited severely increased numbers of spontaneous peritoneal metastases compared to WT mice following the orthotopic injection of syngeneic B16F10 melanoma cells [79]. Importantly, AKAP12 deficiency had no effect on primary tumor growth. This indicates that AKAP12 can control metastatic progression through both tumor- and microenvironment-specific mechanisms.

Figure 4. Increased markers of senescence in AKAP12-null prostates and MEF.

The hyperplastic prostates in Akap12−/− (KO) vs. WT mice display increased staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (“SAβgal”) (Panel A)(inset: percent of SAβgal-positive cells), p16Ink4a (Panel B)(insets: percent of p16-positive cells; AP, anterior prostate; VP, ventral prostate; LP, lateral prostate), and γH2AX (Panel C) as described in Akakura et al. [22]. Karyotype analysis of AKAP12-null MEF shows near tetraploid chromosome numbers (78 in this cell, Panel D).

Future directions

Experiments are underway to more directly address the metastasis suppressor role of AKAP12, especially to characterize how this role is manifested at the molecular mechanism. These include crossing the Akap12−/− background into mice with a prostate-specific deletion of Rb (Pb-Cre;Rbfl/fl). The Akap12−/−;Pb-Cre;Rbfl/fl mice exhibit significantly increased frequencies of lymph node metastases that display transitional basal-luminal phenotypes (Poster 56, AACR Advances in Cancer Research Meeting, Orlando, FL, Feb. 6–9, 2012). Additionally, we are determining the role of AKAP12 expressed by microenvironmental cells, such as fibroblasts and CD11b myeloid cells, in controlling metastatic potential to the peritoneum using the B16F10 melanoma model (above). It is still unclear why AKAP12 might manifest more suppressive roles in metastasis rather than in cancer initiation or maintenance, although this may translate to AKAP12’s ability to attenuate Src-directed metastasis-specific pathways as described above. Nonetheless, it will be important to characterize treatments such as retinoids or inhibitors of histone deacetylation or DNA methylation as means to suppress metastatic progression via the re-expression of AKAP12.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by funding from the NIH (CA94108), DOD (PC074228, PC061246, BC086529) and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation.

Reference List

- 1.Gelman IH. Emerging Roles for SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 in the Control of Cell Proliferation, Cancer Malignancy, and Barriergenesis. Genes & Cancer. 2010;1(11):1147–1156. doi: 10.1177/1947601910392984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malbon CC. A-kinase anchoring proteins: trafficking in G-protein-coupled receptors and the proteins that regulate receptor biology. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery and Development. 2007;10(5):573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HS, Han J, Bai HJ, Kim KW. Brain angiogenesis in developmental and pathological processes: regulation, molecular and cellular communication at the neurovascular interface. FEBS Journal. 2009;276(17):4622–4635. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zan L, Wu H, Jiang J, Zhao S, Song Y, Teng G, Li H, et al. Temporal profile of Src, SSeCKS, and angiogenic factors after focal cerebral ischemia: correlations with angiogenesis and cerebral edema. Neurochemistry International. 2011;58(8):872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon T, Grove B, Loftus JC, O’Toole T, McMillan R, Lindstrom J, Ginsberg MH. Molecular cloning and prelimnary characteriztion of a novel cytoplasmic antigen recognized by myasthenia gravis sera. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;90:992–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI115976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki H, Kunimatsu M, Funii Y, Yamakawa Y, Fukai I, Kiriyama M, Nonaka M, et al. Autoantibody to gravin is expressed more strongly in younger and nonthymomatous patients with myasthenia gravis. Surgery Today. 2001;31(11):1036–1037. doi: 10.1007/s005950170020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin X, Tombler E, Nelson PJ, Ross M, Gelman IH. A novel src- and ras-suppressed protein kinase C substrate associated with cytoskeletal architecture. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(45):28430–28438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapline C, Mousseau B, Ramsay K, Duddy S, Li Y, Kiley SC, Jaken S. Identification of a major protein kinase C-binding protein and substrate in rat embryo fibroblasts - Decreased expression in transformed cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:6417–6422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauert J, Klauck T, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. Gravin, an autoantigen recognized by serum from myasthenia gravis patients, is a kinase scaffolding protein. Current Biology. 1997;7:52–62. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burack WR, Shaw AS. Signal transduction: hanging on a scaffold. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2000;12(2):211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson G. Signal transduction - Scaffolding proteins - More than meets the eye. Science. 2002;295(5558):1249–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1069828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia W, Gelman IH. Mitogen- and FAK-regulated tyrosine phosphorylation of the SSeCKS scaffolding protein modulates its actin-binding properties. Experimental Cell Research. 2002;277(2):139–151. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan X, Walkiewicz M, Carlson J, Leiphon L, Grove B. Gravin dynamics regulates the subcellular distribution of PKA. Experimental Cell Research. 2009;315(7):1247–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Wang HY, Malbon CC. AKAP5 and AKAP12 form homo-oligomers. Journal of Molecular Signaling. 2011;6(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao S, Wang HY, Malbon CC. AKAP12 and AKAP5 form higher-order hetero-oligomers. Journal of Molecular Signaling. 2011;6(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo LW, Gao L, Rothschild J, Su B, Gelman IH. Control of Protein Kinase C Activity, Phorbol Ester-induced Cytoskeletal Remodeling, and Cell Survival Signals by the Scaffolding Protein SSeCKS/GRAVIN/AKAP12. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(44):38356–38366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin X, Nelson P, Gelman IH. Regulation of G–>S Progression by the SSeCKS Tumor Suppressor: Control of Cyclin D Expression and Cellular Compartmentalization. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(19):7259–7272. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7259-7272.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akakura S, Huang C, Nelson PJ, Foster B, Gelman IH. Loss of the SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 gene results in prostatic hyperplasia. Cancer Research. 2008;68(13):5096–5103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon HB, Choi YK, Lim JJ, Kwon SH, Her S, Kim HJ, Lim KJ, et al. AKAP12 regulates vascular integrity in zebrafish. Experimental Molecular Medicine. 2011;44(3):225–235. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.3.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelman IH. The role of the SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 scaffolding proteins in the spaciotemporal control of signaling pathways in oncogenesis and development. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2002;7:d1782–1797. doi: 10.2741/A879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin X, Gelman IH. Re-expression of the major protein kinase C substrate, SSeCKS, suppresses v-src-induced morphological transformation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 1997;57:2304–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akakura S, Nochajski P, Gao L, Sotomayor P, Matsui S, Gelman IH. Rb-dependent cellular senescence, multinucleation and susceptibility to oncogenic transformation through PKC scaffolding by SSeCKS/AKAP12. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(23):4656–4665. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.23.13974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg RA. The molecular basis of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1995;758:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb24838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia W, Unger P, Miller L, Nelson J, Gelman IH. The Src-suppressed C kinase substrate, SSeCKS, is a potential metastasis inhibitor in prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 2001;61(14):5644–5651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapointe J, Li C, Giacomini CP, Salari K, Huang S, Wang P, Ferrari M, et al. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 2007;67(18):8504–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streb JW, Kitchen CM, Gelman IH, Miano JM. Multiple promoters direct expression of three AKAP12 isoforms with distinct subcellular and tissue distribution profiles. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(53):56014–56023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bu Y, Gelman IH. v-Src-mediated Down-regulation of SSeCKS Metastasis Suppressor Gene Promoter by the Recruitment of HDAC1 into a USF1-Sp1-Sp3 Complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(37):26725–26739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bu Y, Gao L, Gelman IH. Role for transcription factor TFII-I in the suppression Of SSeCKS/Gravin/Akap12 transcription by Src. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;128(8):1836–1842. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi MC, Jong HS, Kim TY, Song SH, Lee DS, Lee JW, Kim TY, et al. AKAP12/Gravin is inactivated by epigenetic mechanism in human gastric carcinoma and shows growth suppressor activity. Oncogene. 2004;23(42):7095–7103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jo U, Whang YM, Kim HK, Kim YH. AKAP12alpha is associated with promoter methylation in lung cancer. Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;38(3):144–151. doi: 10.4143/crt.2006.38.3.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessema M, Willink R, Do K, Yu YY, Yu W, Machida EO, Brock M, et al. Promoter methylation of genes in and around the candidate lung cancer susceptibility locus 6q23–25. Cancer Research. 2008;68(6):1707–1714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonazzi VF, Irwin D, Hayward NK. Identification of candidate tumor suppressor genes inactivated by promoter methylation in melanoma. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2009;48(1):10–21. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori Y, Cai K, Cheng Y, Wang S, Paun B, Hamilton JP, Jin Z, et al. A genome-wide search identifies epigenetic silencing of somatostatin, tachykinin-1, and 5 other genes in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):797–808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, Guan M, Su B, Ye C, Li J, Zhang X, Liu C, et al. Quantitative assessment of AKAP12 promoter methylation in colorectal cancer using methylation-sensitive high resolution melting: Correlation with dukes’ stage. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2010;9(11):862–871. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.11.11633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu W, Gong J, Hu J, Hu T, Sun Y, Du J, Sun C, et al. Quantitative Assessment of AKAP12 Promoter Methylation in Human Prostate Cancer Using Methylation-sensitive High-resolution Melting: Correlation With Gleason Score. Urology. 2011;77(4):1006, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu W, Zhang J, Yang H, Shao Y, Yu B. Examination of AKAP12 promoter methylation in skin cancer using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting analysis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2010;36(4):381–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mardin W, Petrov K, Enns A, Senninger N, Haier J, Mees S. SERPINB5 and AKAP12 -- Expression and promoter methylation of metastasis suppressor genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):549. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heller G, Schmidt WM, Ziegler B, Holzer S, Mullauer L, Bilban M, Zielinski CC, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional response to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and trichostatin a in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Research. 2008;68(1):44–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Qin R, Ma Y, Wu H, Peters H, Tyska M, Shaheen NJ, et al. Differential gene expression in normal esophagus and Barrett’s esophagus. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;44(9):897–911. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin Z, Cheng Y, Gu W, Zheng Y, Sato F, Mori Y, Olaru AV, et al. A multicenter, double-blinded validation study of methylation biomarkers for progression prediction in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Research. 2009;69(10):4112–4115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin Z, Hamilton JP, Yang J, Mori Y, Olaru A, Sato F, Ito T, et al. Hypermethylation of the AKAP12 promoter is a biomarker of Barrett’s associated esophageal neoplastic progression. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(1):111–117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai Q, Wen W, Qu S, Li G, Egan KM, Chen K, Deming SL, et al. Replication and Functional Genomic Analyses of the Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 6q25.1 Generalize Its Importance in Women of Chinese, Japanese, and European Ancestry. Cancer Research. 2011;71(4):1344–1355. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He ML, Chen Y, Chen Q, He Y, Zhao J, Wang J, Yang H, et al. Multiple gene dysfunctions lead to high cancer-susceptibility: evidences from a whole-exome sequencing study. American Journal of Cancer Research. 2011;1(4):562–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashi M, Nomoto S, Kanda M, Okamura Y, Nishikawa Y, Yamada S, Fujii T, et al. Identification of the a kinase anchor protein 12 (AKAP12) gene as a candidate tumor suppressor of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012;105(4):381–386. doi: 10.1002/jso.22135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Lee ST, Won HH, Kim S, Kim MJ, Kim HJ, Kim SH, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with susceptibility to chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(25):6906–6911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daoud SS, Munson PJ, Reinhold W, Young L, Prabhu VV, Yu Q, LaRose J, et al. Impact of p53 knockout and topotecan treatment on gene expression profiles in human colon carcinoma cells: a pharmacogenomic study. Cancer Research. 2003;63(11):2782–2793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Ma L, Enkemann SA, Pledger WJ. Role of Gadd45alpha in the density-dependent G1 arrest induced by p27(Kip1) Oncogene. 2003;22(27):4166–4174. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoo JY, Huso DL, Nathans D, Desiderio S. Specific ablation of Stat3beta distorts the pattern of Stat3-responsive gene expression and impairs recovery from endotoxic shock. Cell. 2002;108(3):331–344. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Maltby KM, Miano JM. A novel retinoid-response gene set in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Communications. 2001;281(2):475–482. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Streb JW, Long X, Lee TH, Sun Q, Kitchen CM, Georger MA, Slivano OJ, et al. Retinoid-induced expression and activity of an immediate early tumor suppressor gene in vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmer HG, Sanchez-Carbayo M, Ordonez-Moran P, Larriba MJ, Cordon-Cardo C, Munoz A. Genetic signatures of differentiation induced by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2003;63(22):7799–7806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kovalenko PL, Zhang Z, Cui M, Clinton SK, Fleet JC. 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D-mediated orchestration of anticancer, transcript-level effects in the immortalized, non-transformed prostate epithelial cell line, RWPE1. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ali NA, McKay MJ, Molloy MP. Proteomics of Smad4 regulated transforming growth factor-beta signalling in colon cancer cells. Molecular BioSystems. 2010;6(11):2332–2338. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00016g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nelson P, Gelman IH. Cell-cycle regulated expression and serine phosphorylation of the myristylated protein kinase C substrate, SSeCKS: correlation with cell confluency, G0 phase and serum response. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1997;175:233–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1006836003758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson PS, Clegg N, Arnold H, Ferguson C, Bonham M, White J, Hood L, et al. The program of androgen-responsive genes in neoplastic prostate epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U S A. 2002;99(18):11890–11895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182376299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao C, Wang Y, Yue HH, Zhang YT, Shi CH, Liu F, Bao TY, et al. Biphasic effect of androgens on prostate cancer cells and its correlation with androgen receptor coactivator dopa decarboxylase. Jorunal of Andrology. 2007;28(6):804–812. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.002154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nickols NG, Dervan PB. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, U S A. 2007;104(25):10418–10423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh AP, Bafna S, Chaudhary K, Venkatraman G, Smith L, Eudy JD, Johansson SL, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling reveals transcriptomic variation and perturbed gene networks in androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Letters. 2008;259(1):28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen SB, Waha A, Gelman IH, Vogt PK. Expression of a down-regulated target, SSeCKS, reverses v-Jun-induced transformation of 10T1/2 murine fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2001;20(2):141–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gelman IH, Gao L. The SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 Metastasis Suppressor Inhibits Podosome Formation Via RhoA- and Cdc42-Dependent Pathways. Molecular Cancer Research. 2006;4(3):151–158. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson PJ, Moissoglu K, Vargas JJ, Klotman PE, Gelman IH. Involvement of the protein kinase C substrate, SSeCKS, in the actin-based stellate morphology of mesangial cells. Journal of Cell Science. 1999;112(3):361–370. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee SW, Jung KH, Jeong CH, Seo JH, Yoon DK, Suh JK, Kim KW, et al. Inhibition of endothelial cell migration through the downregulation of MMP-9 by A-kinase anchoring protein 12. Molecular Medicine Report. 2011;4(1):145–149. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2010.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su B, Bu Y, Engelberg D, Gelman IH. SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 inhibits cancer cell invasiveness and chemotaxis by suppressing a PKC-RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(7):4578–4586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.073494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee H, Volonte D, Galbiati F, Iyengar P, Lublin DM, Bregman DB, Wilson MT, et al. Constitutive and growth factor-regulated phosphorylation of caveolin-1 occurs at the same site (Tyr-14) in vivo: identification of a c-Src/Cav-1/Grb7 signaling cassette. Molecular Endocrinology. 2000;14(11):1750–1775. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.11.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rinker-Schaeffer CW, O’Keefe JP, Welch DR, Theodorescu D. Metastasis suppressor proteins: discovery, molecular mechanisms, and clinical application. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(13):3882–3889. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su B, Zheng Q, Vaughan MM, Bu Y, Gelman IH. SSeCKS metastasis-suppressing activity in MatLyLu prostate cancer cells correlates with VEGF inhibition. Cancer Research. 2006;66(11):5599–5607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eliceiri BP, Paul R, Schwartzberg PL, Hood JD, Leng J, Cheresh DA. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(6):915–924. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eliceiri BP, Puente XS, Hood JD, Stupack DG, Schlaepfer DD, Huang XZZ, Sheppard D, et al. Src-mediated coupling of focal adhesion kinase to integrin alpha v beta 5 in vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157(1):149–159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weis S, Cui J, Barnes L, Cheresh D. Endothelial barrier disruption by VEGF-mediated Src activity potentiates tumor cell extravasation and metastasis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;167(2):223–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee SW, Kim WJ, Choi YK, Song HS, Son MJ, Gelman IH, Kim YJ, et al. SSeCKS regulates angiogenesis and tight junction formation in blood-brain barrier. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(7):900–906. doi: 10.1038/nm889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adluri RS, Thirunavukkarasu M, Zhan L, Akita Y, Samuel SM, Otani H, Ho YS, et al. Thioredoxin 1 Enhances Neovascularization and Reduces Ventricular Remodeling During Chronic Myocardial Infarction: A Study Using Thioredoxin 1 Transgenic Mice. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;50(1):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi YK, Kim JH, Kim WJ, Lee HY, Park JA, Lee SW, Yoon DK, et al. AKAP12 regulates human blood-retinal barrier formation by downregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(16):4472–4481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5368-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi YK, Kim KW. AKAP12 in astrocytes induces barrier functions in human endothelial cells through protein kinase Czeta. FEBS Journal. 2008;275(9):2338–2353. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steagall RJ, Hua F, Thirunazukarasu M, Zhan L, Li C, Maulik N, Han Z. HspA12B Promotes Angiogenesis through Suppressing AKAP12 and Up-Regulating VEGF Pathway. Angiogenesis. 2010;118:S449. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu W, Guan M, Hu T, Gu X, Lu Y. Re-expression of AKAP12 inhibits progression and metastasis potential of colorectal carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e24015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akakura S, Bouchard R, Bshara W, Morrison C, Gelman IH. Carcinogen-induced squamous papillomas and oncogenic progression in the absence of the SSeCKS/AKAP12 metastasis suppressor correlates with FAK upregulation. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;129(8):2025–2031. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohtani N, Mann DJ, Hara E. Cellular senescence: its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Science. 2009;100(5):792–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLean GW, Brown K, Arbuckle MI, Wyke AW, Pikkarainen T, Ruoslahti E, Frame MC. Decreased focal adhesion kinase suppresses papilloma formation during experimental mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 2001;61(23):8385–8389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Akakura S, Su B, Nochajski P, Foster B, Huang C, Nelson PJ, Gelman IH. SSeCKS/Gravin/AKAP12 suppresses metastasis through tumor- and microenvironment-specific pathways. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2009;26(7):864, A49. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daigeler A, Klein-Hitpass L, Chromik MA, Muller O, Hauser J, Homann HH, Steinau HU, et al. Heterogeneous in vitro effects of doxorubicin on gene expression in primary human liposarcoma cultures. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:313. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, McKee M, et al. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. Cancer Research. 2009;69(7):3077–3085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Radvanyi L, Singh-Sandhu D, Gallichan S, Lovitt C, Pedyczak A, Mallo G, Gish K, et al. The gene associated with trichorhinophalangeal syndrome in humans is overexpressed in breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, U S A. 2005;102(31):11005–11010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500904102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]