Abstract

The secretory protein Slit2 and its receptors Robo1 and Robo4 are considered to regulate mobility and permeability of endothelial cells and other cell types. However, the roles of Slit2 and its two receptors in endothelial inflammatory responses remain to be clarified. Here we show that, in primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), Slit2 represses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced secretion of certain inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1 upregulation and monocyte adhesion. Slit2 anti-inflammatory effect is mediated by its dominant endothelial specific receptor Robo4. However the minor receptor Robo1 has pro-inflammatory properties, and is downregulated by Slit2 via targeting of miR-218. Elucidation of molecular mechanism reveals that Slit2 represses inflammatory responses by inhibiting the Pyk2-NF-kB pathway downstream of LPS-TLR4. Further studies reveal that LPS enhances endothelial inflammation by downregulating the anti-inflammatory Slit2 and Robo4 in HUVECs in vitro as well as in arterial endothelial cells and liver in vivo during endotoxemia. These results suggest that Slit2-Robo4 signaling is important in regulating LPS-induced endothelial inflammation, and LPS, in turn, enhances inflammation by interfering with the expression of the anti-inflammatory Slit2-Robo4 during disease state. This implies that Slit2-Robo4 is a key regulator of endothelial inflammation and its dysregulation during endotoxemia is a novel mechanism for LPS-induced vascular pathogenesis.

Introduction

Endothelial inflammation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of sepsis shock induced organ injury and atherosclerosis (1, 2). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria is one of the main inflammatory pathogen in sepsis shock and atherogenesis (3–5). LPS induces inflammation by directly activating the vascular endothelium and monocyte/macrophages system and eliciting a series of specific cell responses, including an increase of cell adhesion molecule and pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression in the endothelial cells (6). This leads to hyperpermeability of endothelium and recruitment of leukocytes (especially monocyte/macrophage) to enhance inflammation (3). Both the enhanced vascular permeability and the increased monocyte adhesion on endothelial cells are thought to play important roles in pathogenesis of sepsis shock and atherosclerosis (3).

Slit and Robo are evolutionarily conserved proteins, which are widely expressed in different tissues (7–9). The secretory protein Slit has 3 isoforms, Slit1-3, and it has 4 different membrane receptors, named Robo1-4 (7, 8, 10). Robo1-3 are expressed in a broad tissue spectrum, but Robo4 is specifically expressed in endothelial cells (11–14). Slit2 is present in blood and is also expressed in endothelial cells (13, 15, 16). Slit2-induced signaling has different roles in different cell types, such as regulating axon guidance in neuronal cells, regulating chemotaxis and HIV infection in leukocytes, regulating metastasis and proliferation in carcinoma cells and regulating angiogenesis in endothelial cells (11, 13, 17–22). In endothelial cells, Slit2 functions by binding to its receptor Robo1 and Robo4 (11, 12, 23), subsequently inducing a series of intracellular signaling events (13, 24). Slit2 was shown to regulate angiogenesis (11, 23, 25) and protect endothelial integrity during sepsis and when exposed to HIV (13, 24). However, not much is known about the role of Slit2 in regulating endothelial inflammatory responses other than increase of permeability.

With its critical regulating functions, Slit2 signaling is often dysregulated or deficient in pathological status. Slit2 and Robo1 are commonly silenced by DNA methylation in several human cancers (17, 26–28), and the expression of Slit2 can also be regulated by cytokines (13) (29). However, there is no report showing the regulation of Slit-Robo expression during inflammation. Thus it is important to understand the role of LPS in regulating Slit and Robo expression and disease progression with in vitro and in vivo models.

MicroRNAs are short non-coding RNAs that regulate the translation and/or degradation of target messenger RNAs (30). They have been shown to regulate the pathogenesis of numerous diseases (31, 32). miR-218 is a microRNA that is broadly expressed in different tissues, including endothelial cells (15, 33, 34). One of the precursors of miR-218, mir-218-1, is encoded in the intron of Slit2 genes, and it is expressed along with Slit2 protein (15, 33). One of the main targets of miR-218 is Robo1, and miR-218 represses Robo1 expression by inhibiting its translation (15, 33, 34). So it is possible that miR-218 also plays a role in regulating Slit2 signaling during endothelial inflammation.

In the present study, we characterized the role of Slit2 signaling in regulating LPS-induced endothelial inflammatory responses. Based on in vitro and in vivo studies, we have also proposed a novel pathogenic model of endotoxemia involving LPS-induced endothelial inflammation and liver injury through modulating Slit2 signaling.

Methods

Reagents and cells

LPS from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, 600000 EU/mg and less than 0.80% protein contamination as shown by the manufacturer’s certificate of analysis), was dissolved in PBS. N-terminal human Slit2 (Slit2-N) protein and Oct1 antibody were obtained from AbCam (Cambridge, MA). ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Slit2, Robo1 and Robo4 polyclonal antibodies were obtained from AbCam. p-Pyk2 (Y402) and Pyk2 antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). TLR4 antibody (neutralizing) was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Pyk2 inhibitor Tyrphostin A9 was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), and PF431396 was obtained from Pfizer (New York, NY). HUVECs, obtained from ScienCell Research Labortories (Carlsbad, CA), were cultured in complete ECM medium (ScienCell). Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs, adult dermis) (Clonetics, San Diego, CA) were maintained in EGM-2MV growth medium containing growth factors, antimicrobials, cytokines and 5% FBS. HUVECs and HMVECs were grown to confluency in tissue culture plates before treatment with LPS and/or Slit2-N. THP-1 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent program), a human monocytic cell line, was grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Invitrogen) and P/S antibiotics. Human multiple tissue cDNA panel was obtained from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain View, CA).

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) and purified with RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Total RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was then performed on Eppendorf Mastercycler realplex using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies). Data analysis was performed using standard “delta delta Ct method”.

Cytokine secretion quantification assay

Cumulative cytokine secretion in the supernatant of HUVEC culture under different treatments was detected with Human Cytokine Array Kit, Panel A, from R&D Systems according to the manufacturer’s manual. Confluent HUVECs were pre-treated with Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) or PBS as control for 30–60 min. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or PBS as negative control for 12 h before the supernatant of each group was collected. Assays were performed in duplicates, and quantified by densitometry with ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western Blotting (WB)

WB was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, proteins in cell lysates were separated by electrophoresis using NuPAGE SDS PAGE Gel (Life Technologies). Proteins transferred onto Nitrocellulose membrane were then blotted by specific primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein expression was detected by Thermo ECL reagents using X-ray films.

Cell adhesion assay

THP-1 cell adhesion on HUVECs assay was modified from the method reported previously (35). Briefly, HUVECs were grown to confluency in 96-well plates. HUVECs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6h with or without Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) pre-treatment before washing with warm complete RPMI. THP-1 cells were washed and stained with 1μmol/L CFSE (Life Technologies) in PBS for 5 min. 106 THP-1 cells (5×106 cells/mL) were added onto treated HUVECs for 60 min. Cells were then washed with warm medium and fluorescence intensity was detected using Synergy 2 Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

siRNA knock down

siRNA-mediated knockdown of Robo1 and Robo4 was performed using Robo1- and Robo4-specific ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). Briefly, confluent HUVECs were transfected with 200 pmol siRNA per well in 6-well plates using TransPass HUVEC Transfection Reagent (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Non-targeting small RNA was used as control.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and surface proteins were detected with specific primary antibodies coupled with Alexa Fluor 488/568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies). Data were acquired using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using CellQuest 5.0.

NF-kB activity assay and MCP-1 ELISA assay

HUVECs, with or without Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) pre-treatment, were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 4h before harvest. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extractions of cells were then prepared using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Scientific) per the product manual. Activated NF-kB levels of both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were measured using TransAM NF-kB p65 Transcription Factor ELISA Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) per the product manual. MCP-1 concentration in the HMVEC culture supernatants was detected using MCP-1 ELISA kit (Invitrogen) per the product manual.

in vivo endotoxemia study

Male C57BL/6 mice at 12-week age were randomly separated into 2 groups, 5 per group. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2.5 mg/kg LPS (E. coli O111:B4 from Sigma-Aldrich, 1 mg/mL in PBS) or equal amount of PBS (saline) as control. 24 hours after injection, mice were euthanized with CO2. Immediately, aorta and main arteries connecting to the heart were isolated, liver removed. Aortic endothelial cells were isolated by the method adapted from Chen et al (36). Blood was emptied from arteries, and lumen washed with PBS. Then about 50 μL of 37°C enzyme solution (0.25% trypsin and 225 U/mL collagenase type II in RPMI with 25 mmol/L HEPES) was injected into the lumen of arteries with one end tied. After digestion for 1 minute, enzyme solution was collected. This was repeated 5 times and endothelial cells were isolated by centrifuge. The purity of isolated endothelial cells was detected by flow cytometry with murine CD31 antibody (Santa Cruz). To detect specific gene expression, liver tissue and aortic endothelial cells were homogenized and RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR analysis as stated above. All mice were kept in the animal facility of Ohio State University in compliance with the guidelines and protocols approved by the IACUC.

Immunohistochemistry staining (IHC)

IHC was performed as previously described (37). Briefly, samples from mouse livers were dissected, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for sections. Standard IHC techniques were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Vector Laboratories) using antibodies against CD31 (Santa Cruz 1:100) and Robo4 (Abcam, 1:200). Vectastain Elite ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories), coupled with avidin DH:biotinylated horseradish peroxidase H complex with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Polysciences) and Mayer’s hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific), were used for detection of the bound antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Reported data for cell line studies are the means ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate or triplicate. The animal study was done with N=5 mice per group. The statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t test. Linear regression analysis was used to determine dependence/correlation between Slit2 and Robo1 expression levels.

Results

Slit2 inhibits LPS-induced cytokine expression

Studies have shown that Slit2 can be cleaved into a 120–140 kDa N-terminal and a C-terminal fragment, and the biological effects of Slit2 are mediated by the N-terminal fragment which interacts with its receptor Robo (7, 22, 24). Here, we used N-terminal Slit2 (Slit2-N) to elaborate its effect.

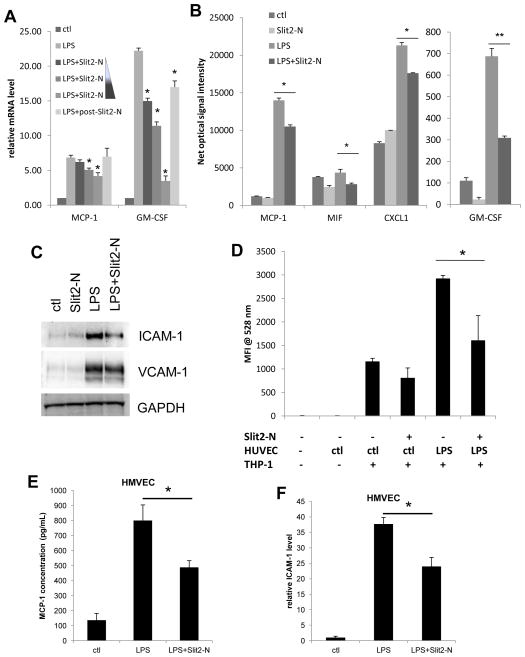

In the pathogenesis of sepsis shock induced organ injury and atherosclerosis, LPS stimulated endothelial cells can initiate and enhance topical and systematic inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which increase permeability of endothelium and recruit and activate leukocytes to clear the infection. To examine the role of Slit2 in regulating LPS-induced endothelial inflammation, we first analyzed its role in pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression. Slit2-N pre-treatment significantly inhibited LPS stimulated Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1 (MCP-1, CCL2) and Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) expression at the mRNA level by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) in HUVECs in a dose dependent manner (Figure 1A). In accordance with the mRNA level, Slit2-N pre-treatment also significantly inhibited cumulative MCP-1 and GM-CSF secretion at protein level after 12 h stimulation with LPS. Besides, LPS-induced secretion of CXCL1 (GROα) and Macrophage migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) were also significantly inhibited by Slit2-N treatment (Figure 1B). Moreover, Slit2-N also inhibited LPS-induced MCP-1 secretion in HMVECs (Figure 1E). However, Slit2-N did not significantly affect the LPS-induced secretion of other common inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-1β (data not shown). Meanwhile, Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) treatment 30min after LPS stimulation showed much less effect on cytokine expression (Figure 1A), which suggests that Slit2 may regulate the LPS-induced cellular signaling. These data indicate that Slit2 can repress LPS-induced endothelial inflammatory response by inhibiting secretion of certain cytokines/chemokines. These affected cytokines/chemokines are well known for their functions in inducing endothelial tight junction disruption, leukocyte recruitment and activation.

Figure 1. Slit2-N inhibited the LPS-induced cytokine and cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1 expression in HUVECs as well as monocyte adhesion on HUVECs.

HUVECs were treated with 100ng/mL LPS for 2 h (A) or 12 h (B) with or without treatment of Slit2-N. (A) Cells were stimulated by LPS with pre-treatment of a gradient of 3 nmol/L, 30 nmol/L and 60 nmol/L Slit2-N or post-treatment with 30 nmol/L Slit2-N (post-Slit2-N). Total RNA was isolated and qRT-PCR was performed to detect mRNA expression level of MCP-1 and GM-CSF. Values are normalized to control group, and are not comparable between cytokines. (B) Cell culture supernatants were collected after Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) plus LPS treatment. Cytokines secreted in the supernatants were detected with R&D cytokine array kit. Values are net optical signaling intensity. (C) HUVECs were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 12 h with or without pre-treatment of Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). Cells were lysed and WB was performed using ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and GAPDH antibodies. (D) HUVECs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6 h with or without Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). CFSE labeled THP-1 monocytic cells were added onto treated HUVEC. And after washing, attached THP-1 cells were quantified by mean fluorescence intensity at 528nm. (E) HMVECs were stimulated with 100ng/mL LPS in the presence or absence of 30 nmol/L Slit2-N for 12 h. Supernatant MCP-1 secretion was analyzed by ELISA. (F) ICAM-1 expression was detected by qRT-PCR in HMVECs with LPS stimulation in the presence or absence of Slit2-N. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01)

Slit2 inhibits LPS-induced cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1 expression and monocyte adhesion on endothelial cells

During LPS-induced endothelial inflammation, endothelial cells upregulate the expression of cell adhesion molecules including ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 to increase leukocyte (including monocytes) attachment. Recruited monocytes are critical in atherogenesis and enhancement of inflammation. We observed that Slit2-N treatment potently inhibited LPS-induced ICAM-1 protein expression without significantly affecting VCAM-1 (Figure 1C). Moreover, Slit2-N also inhibited ICAM-1 upregulation by LPS in HMVECs (Figure 1F). To check whether this inhibition of ICAM-1 expression influences monocyte adhesion on endothelial cells, we performed cell adhesion assay with monocytic cell line THP-1 and HUVECs. LPS treatment enhanced THP-1 adhesion on HUVEC, and Slit2-N treatment to HUVECs significantly decreased THP-1 adhesion upon stimulation of LPS (Figure 1D). These results suggest that Slit2 can decrease LPS-induced monocyte adhesion on endothelial cells by inhibiting ICAM-1 expression.

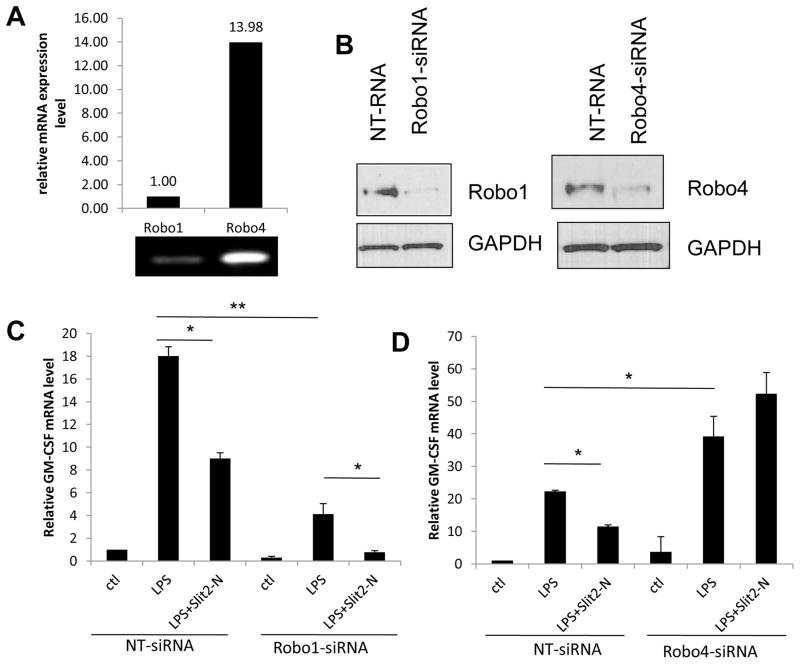

Anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2 is mediated through Robo4 rather than Robo1

Slit2 is a secreted signaling molecule which functions by binding to its receptor Robo and subsequently inducing a series of intracellular signaling events. Given that Slit2 inhibits LPS-induced cytokine/chemokine expression, we wanted to verify whether the effect of Slit2 was mediated through Slit2-Robo interaction. Moreover, among the two endothelial Slit2 receptors, Robo4 is much more abundantly expressed in endothelial cells than Robo1 (Figure 2A). Thus we set out to identify which Robo receptor is responsible for the effect of Slit2 on LPS-induced inflammation in endothelial cells. GM-CSF mRNA expression was used as the indicator of endothelial inflammation, which was inhibited by Slit2 (Figure 1A, B). Robo1 was knocked down in HUVECs using Robo1-siRNA (Figure 2B), and GM-CSF expression was measured by qRT-PCR at the mRNA level after 2 hours of LPS stimulation. Slit2 inhibited LPS-induced GM-CSF expression in non-targeting siRNA transfected cells as well as Robo1-siRNA group (Figure 2C), which shows that the anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2 is not dependent on Robo1 receptor. In contrast, Slit2 enhanced LPS-induced GM-CSF expression when Robo4 was knocked down in HUVECs (Figure 2B, D), which showed that the anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2 was mediated through Robo4 receptor. Whereas Robo1 could be pro-inflammatory, considering LPS-induced GM-CSF is less after Robo1 knock down and it is more after Robo4 knock down. These results suggested that Slit2 mediates its anti-inflammatory effects in endothelial cells through Robo4 rather than Robo1. Since Robo4 is dominantly expressed (Figure 2A), the overall effect of Slit2 treatment is anti-inflammatory in endothelial cells.

Figure 2. The anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2 was dependent on Robo4 rather than Robo1.

(A) Robo1 and Robo4 relative mRNA expression level in resting HUVECs were quantified by qRT-PCR, and PCR product was shown on Agarose Gel. (B) 48 h after transfection with Robo1-or Robo4-siRNA, HUVECs were lysed and WB was used to detect the protein levels of Robo1 and Robo4. GAPDH was used as loading control. (C and D) 48 h after Robo1 and Robo4 knocking down respectively, GM-CSF mRNA expression in HUVECs was analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 h after LPS (100 ng/mL) treatment with or without Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). Non-targeting siRNA was used as control for Robo1- or Robo4-siRNA. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01)

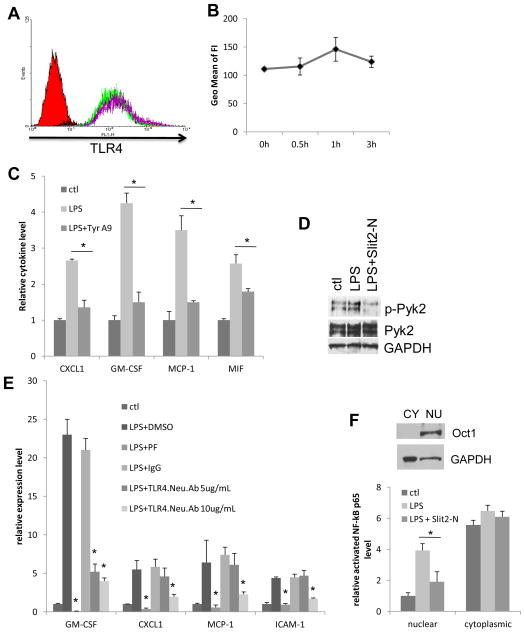

Slit2 represses LPS-induced endothelial inflammation by inhibiting the Pyk2 - NF-kB pathway

Next, we analyzed the molecular mechanism by which Slit2 inhibits LPS-induced endothelial inflammation. We observed that Slit2 did not change the surface level of TLR4 on HUVECs (Figure 3A, B). This indicates that Slit2 affects LPS-triggered intracellular signaling. It has been reported that upon binding to TLR4, LPS activates Pyk2 through phosphorylation, which then activates NF-kB and initiates NF-kB translocation into the nucleus to start the transcription of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. It has been reported that Pyk2 is important for LPS-induced chemokine IL-8 and MCP-1 expression in endothelial cells (38, 39). Here, by inhibiting Pyk2 activation using a Pyk2 inhibitor Tyrphostin A9 (39), we also showed that Pyk2 is important for LPS-induced MCP-1, CXCL1, MIF and GM-CSF expression, which were repressed by Slit2 (Figure 3C). Then we confirmed that Slit2-N treatment significantly inhibited LPS-induced phosphorylation of Pyk2 (Figure 3D). In addition, high concentration TLR4 neutralizing antibody and a potent and highly specific Pyk2 inhibitor PF431396 prevented LPS-induced cytokine expression at the transcriptional level (Figure 3E). This confirmed that LPS-induced cytokine gene transcription is mediated by TLR4-Pyk2 signaling. Next, downstream of Pyk2, we analyzed the NF-kB activation and its nuclear translocation in the presence and absence of Slit2 in HUVECs using ELISA-based NF-kB activity assay. We extracted the cytoplasmic and nuclear portions of HUVEC cell lysates, and the purity was indicated by the levels of nuclear protein Oct1 and GAPDH (mainly present in the cytoplasm) (Figure 3F). Slit2-N treatment decreased the LPS-induced activation and nuclear translocation of NF-kB (Figure 3F). This indicates that Slit2 treatment inhibited LPS-induced Pyk2 activation and further decreased the downstream activation and nuclear translocation of NF-kB in HUVECs.

Figure 3. Slit2 inhibits LPS-induced Pyk2 activation and NF-kB activation and translocation.

(A) Surface levels of TLR4 on HUVECs with Slit2-N (30 nmol/L) for different time (0, 0.5, 1 and 3 h) were analyzed by flow cytometry. IgG isotype control is shown as a solid peak in the histogram, TLR4 levels at different time points as open peaks of colored lines. (B) Flow cytometry data is quantified by mean fluorescence intensity and summarized in 3B. Changes are not statistically significant. (C) HUVECs were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 12 h with or without pre-treatment of Pyk2 inhibitor Tyrphostin A9 (Tyr A9, 10 μmol/L). Cell culture supernatants were collected after treatment. Cytokines secreted in the supernatants were detected with R&D cytokine array kit. Values are relative net optical signal intensity and are not comparable between cytokines. (D) HUVECs were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 2 h with or without pre-treatment of Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). Phosphorylated Pyk2 was detected by WB using p-Pyk2 (Y402) and Pyk2 antibodies. GAPDH was used as loading control. (E) HUVECs were pre-treated with Pyk2 inhibitor PF431396 (PF, 10 μmol/L), the indicated concentration of TLR4 neutralizing antibody (TLR4.Neu.Ab) or their controls for 1h and then stimulated with LPS for 2 h. Protein expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (F) Representative cytoplasmic (CY) and nuclear (NU) portions of HUVEC cell lysates were probed for nuclear marker Oct1 (exclusively in nuclear portion) and cytoplasmic marker GAPDH (mostly in cytoplasmic portion). HUVECs were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 4 h with or without pre-treatment of Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). Cells were then lysed, nuclear and cytoplasmic portions were separated. Active NF-kB was detected by an ELISA-based assay. (*p<0.05)

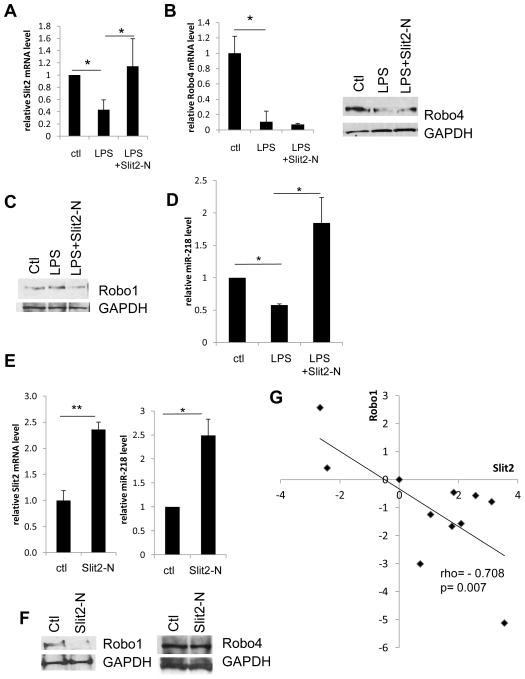

LPS enhances endothelial inflammation by downregulating Slit2 and Robo4

We have shown above that in endothelial cells, Slit2 and Robo4 are anti-inflammatory. Thus we asked the question whether LPS has any effect on the expression of Slit2 and Robo4, and whether this effect may contribute to endothelial inflammation. By qRT-PCR and Western Blotting (WB) analysis, we observed that LPS stimulation significantly downregulated Slit2 and Robo4 in HUVECs, without significantly changing Robo1 level (Figure 4A-C). This showed that LPS may enhance endothelial inflammation by downregulating anti-inflammatory molecules Slit2 and Robo4.

Figure 4. The modulation of Slit2, Robo1 and Robo4 expression and the role of miR-218.

(A, B) HUVECs were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 2 h with or without pre-treatment of Slit2-N (30 nmol/L). qRT-PCR was used to detect mRNA expression of Slit2 and Robo4. In accordance with mRNA level, protein levels of Robo4 in treated HUVECs for 12 h were shown as WB. (C) Protein levels of Robo1 in the above treated HUVECs or Robo1 of HUVECs treated only with Slit2-N for 12 h were shown by WB. (D) miR-218 level was detected by miR-218-specific qRT-PCR primers in HUVECs treated with LPS in the presence or absence of Slit2-N (30 nmol/L), and that of HUVECs treated with Slit2-N or PBS as control for 2 h. (E) Slit2-N treatment per se induced Slit2 and miR-218 upregulation as shown by qRT-PCR. (F) Slit2-N treatment per se reduced Robo1 expression, without affecting Robo4. (G) Slit2 and Robo1 expression levels in 10 different human tissues were detected using qRT-PCR with human multiple tissue cDNA panel (ovary, prostate, kidney, colon, heart, small intestine, liver, pancreas, lung and skeletal muscle). Values were normalized to human normal tissue control. Each dot stands for one human tissue with Slit2 and Robo1 expression levels on two axes. Correlation coefficient rho and p values are labeled in the plot. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01)

Slit2 downregulates Robo1 protein level through upregulation of miR-218

Slit2-N treatment not only inhibited LPS-induced inflammation, but also upregulated Slit2 and downreguated Robo1 expression (Figure 4A, C). It has been reported that primary microRNA, mir-218-1, located in the intron of Slit2 gene, and mature miR-218 is expressed along with Slit2 as they share the same transcript. Thus we hypothesized that downregulation of Robo1 could be mediated through miR-218, which targets 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of Robo1 and inhibits its protein translation. We observed that cellular miR-218 level consistently change with Slit2 mRNA level in similar fashion (Figure 4A, D). In addition, Slit2-N treatment per se significantly increased both Slit2 and miR-218 level, the latter of which knocked down Robo1, leaving Robo4 unchanged (Figure 4E, F). This indicates that there is a positive feedback regulation of Slit2 expression, and Slit2 treatment can regulate Robo1 receptor expression via intronic miR-218. Similar to our findings in Figure 4, this repressing effect of Slit2 towards Robo1 expression appears to be universal in different human tissues. By analyzing the Slit2 and Robo1 expression levels in a human tissue panel, we observed a strong negative correlation between Slit2 and Robo1 (Figure 4G). This negative correlation could be at least partially mediated by miR-218.

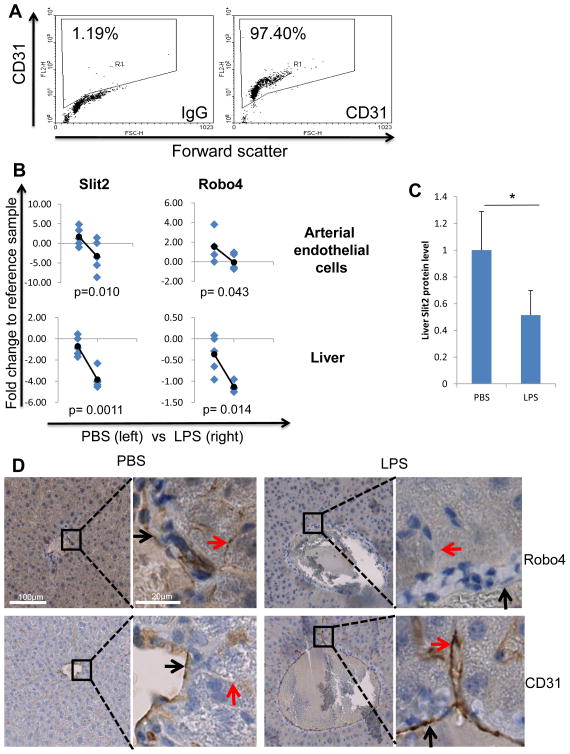

LPS downregulates Slit2 and Robo4 expression in arterial endothelial cells and in liver during endotoxemia in vivo

With the observation that LPS-regulated Slit2 and Robo4 expression in HUVECs in vitro, we wanted to verify whether LPS also regulates their expression during endotoxemia (sepsis) in vivo using a mouse model. During endotoxemia/sepsis shock, multiple organ injury (including liver) is one of the main life threatening events caused by endothelial inflammation. Additionally, inflammation of arterial endothelial cells caused by LPS is important for atherosclerosis development. Thus we planned to analyze the expression changes in mouse arterial endothelial cells and whole liver. Male C57BL/6 mice at 12-week age were intraperitoneally injected with 2.5 mg/kg LPS or saline. 24 hours after injection, mice were sacrificed and the liver and the aorta removed. We separated aortic endothelial cells from the aorta by enzyme digestion, and 96% of the cells were CD31-positive detected by flow cytometry (Figure 5A). In mouse aortic endothelial cells, LPS significantly downregulated Slit2 and Robo4. Similarly, LPS significantly downregulated the expression of Slit2 and Robo4 in mouse liver (Figure 5B). Since Robo4 is specifically expressed in endothelial cells, its expression in whole liver mainly represent the Robo4 level of liver endothelial cells; while Slit2 expression in the liver represents its overall level in the tissue environment. Both of these observations were in agreement with the changes in HUVECs in vitro. Additionally, we analyzed two other microarray data in the NCBI GEO DATASET Database. They showed similar changes of Slit2 and Robo4 expression upon LPS or pro-inflammatory cytokine stimulation (40) (Table 1). We also observed dramatic downregulation of Slit2 in mouse liver with non-LPS-induced inflammation, including vascular injury and blood leakage (data not shown). Furthermore, we analyzed the Slit2 protein expression by WB and endothelial Robo4 protein level by IHC with mouse liver tissue from LPS or saline group. Liver lysates from mice injected with LPS have less Slit2 expression compared to that of the saline group (Figure 5C). Moreover, after LPS injection, liver main blood vessel endothelial cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells showed significantly less Robo4 expression compared to that of the saline group (Figure 5D). LPS-stimulated upregulation of endothelial cell marker CD31 in mouse liver endothelial cells during endotoxemia is shown as a positive control (Figure 5D). These data showed that LPS downregulated anti-inflammatory Slit2-Robo4 in vivo, which may be responsible for enhancing endothelial inflammation and liver injury.

Figure 5. Slit2, Robo1 and Robo4 in arterial endothelial cells and liver are regulated by LPS during endotoxemia in vivo.

(A) Endothelial cells were isolated from mouse arteries by enzyme digestion. Cells were then stained for CD31 or IgG control and the purity of endothelial cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentage of CD31 positive cells (region R1) was labeled. Left: IgG isotype control antibody. Right: murine CD31 antibody. (B) C57BL/6 mice were i.p. injected with LPS or saline. 24 h later, mice were sacrificed and aortic endothelial cells and liver isolated. qRT-PCR was performed to detect murine Slit2 and Robo4 expression after RNA extraction. Diamond dots representing saline group mice are on the left mark and LPS on the right of each plot. Round-ended lines indicate the change of averages between groups. p values are labeled at the bottom of plots. (C) Liver lysates of mice injected with PBS or LPS were used to detect Slit2 secretion by WB. Quantification of Slit2 secretion from 5 mice of each group is summarized here. (D) Liver samples of LPS and PBS injected mice were fixed and embedded in paraffin. IHC was performed to stain Robo4 and CD31 on overlaying sections. Main blood vessel endothelial cells are indicated by black arrows, and sinusoidal endothelial cells by red arrows. CD31 is used as the endothelial marker. (*p<0.05)

Table 1.

LPS and pro-inflammatory cytokines regulate Slit2 and Robo4 expression

| Reference | Sample | Treatment | Slit2 | Robo1 | Robo4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| t | p | t | p | t | p | |||

| GSE23070 | HUVEC | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8 | −3.02 | 1.24E-02 | 0.36 | 7.65E-01 | −4.68 | 2.59E-04 |

| GSE9667 | Murine heart | i.p. LPS | −2.38 | 1.72E-02 | 0.33 | 7.40E-01 | −2.50 | 1.26E-02 |

Based on NCBI GEO DATASET, GSE23070 studied the treatment of HUVEC by a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8), and GSE9567 studied the effect of LPS i.p. injection on murine heart. Similar to our findings, microarray data from both of these studies indicate that LPS or pro-inflammatory cytokines can regulate Slit2-Robo1/4 signaling. t and p: t value and p value from t test between control and treatment groups. Positive t value indicates increased expression with treatment, negative indicates decreased expression.

Discussion

LPS-induced endothelial inflammation is a critical pathological event in numerous diseases, especially acute endotoxemia/sepsis. We discovered that the secretory protein Slit2 can repress LPS-induced endothelial inflammatory responses, including secretion of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, upregulation of cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1 and monocyte adhesion. The two endothelial receptors Robo1 and Robo4 were shown to play differential roles in endothelial cells, and Slit2-Robo4 interaction is responsible for the anti-inflammatory effects. Slit2 can downregulate the minor receptor Robo1 via miR-218. In addition, LPS was shown to downregulate Slit2-Robo4 to enhance endothelial inflammation in vitro and in vivo.

In the present study, we have shown, for the first time that Slit2 represses certain LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression in HUVECs, including MCP-1, MIF, CXCL1 and GM-CSF. This is in agreement with a study of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) induced multibacterial sepsis (including Gram-negative) in a mouse model, which showed that there is a trend of decease in inflammatory cytokine levels in the serum after Slit2 administration, though not significant (24). The lack of significant differences could be due to mixed and complicated cytokine/chemokine sources in vivo and large detection errors, given that differentiated leukocytes do not express Robo4. In addition, it has been reported that Slit2 can protect LPS and HIV-1 gp120 induced endothelial hyperpermeability by preventing the tight junction disruption (13, 24). Though unlikely, there could be a possibility that Slit2 might also inhibit the increase of accessible membrane TLR4 to LPS during LPS-induced endothelial tight junction breakdown, and this could in part contribute to the anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2. Our work suggests that the protection of endothelial integrity by Slit2 might at least in part be mediated through its repression of inflammatory cytokine induced indirect tight junction disruption. Along with these pro-inflammatory cytokines, some LPS-induced anti-inflammatory cytokines (including sICAM-1 and IL-1Ra) were also repressed by Slit2 (data not shown). However, these anti-inflammatory cytokines are a part of self-protective responses of endothelial cells, and their expression levels are relatively low.

LPS-induced expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs was also inhibited by Slit2. And consequently, LPS-induced THP-1 monocytic cell adhesion was also reduced by Slit2. This function of Slit2 in regulating inflammation has not been reported before. However, similarly, we and other groups have shown that Slit2 can inhibit T cells and platelets adhesion onto endothelial cells or extra cellular matrix proteins by acting on T cells and platelets (16, 35).

In the present study, we have shown that dominant endothelial receptor Robo4 is responsible for the anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2, which supports the findings of another study showing that Slit2-Robo4 can reduce inflammation-induced organ damage and death by protecting endothelial integrity during sepsis. In addition, our data indicate that Robo1 could be pro-inflammatory in endothelial cells. This is a new discovery illustrating the differential roles of Robo1 and Robo4 receptors in endothelial inflammation. However, there are several studies which indicate that Robo1 and Robo4 may have opposite functions in regulating angiogenesis and endothelial cell migration (13, 20, 23–25, 41). Furthermore, in agreement with other studies, we showed that Robo4 is 14 times more abundantly expressed than Robo1, which renders Robo4 the dominant anti-inflammatory endothelial receptor for Slit2.

The proline-rich kinase 2, Pyk2, also known as RAFTK, is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase related to focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and Pyk2 – NF-kB pathway has been shown to be important for LPS-triggered MCP-1 and IL-8 expression in endothelial cells (38, 39). We also showed that Pyk2 is important for LPS-induced expression of MIF, CXCL1 and GM-CSF. Given the importance of Pyk2-NF-kB in LPS-induced cytokine/chemokine expression, our molecular signaling study revealed that Slit2 represses LPS-induced endothelial inflammation through inhibiting LPS-triggered Pyk2 activation as well as NF-kB activation and nuclear translocation. Upstream of Pyk2, the LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine expression was also majorly blocked by the higher concentration of TLR4 neutralizing antibody, though they did not decrease to the control baseline level. This could either be due to incomplete blocking of TLR4 by antibody or due to the effect of trace amount of contaminations (including TLR2 ligand) in the LPS product. miR-218 has been shown to inhibit Robo1 expression in endothelial and other cells (15, 42). Here we showed that Slit2 treatment has a positive feedback to Slit2 and miR-218 expression, and the increased miR-218 in turn inhibits Robo1 protein translation.

Our in vitro and in vivo data indicate, for the first time, that LPS stimulation or endotoxemia can downregulate Slit2 and Robo4 in endothelial cells and in liver. Thus, we hypothesize that LPS enhances endothelial and organ inflammation by impairing the anti-inflammatory Slit2-Robo4 signaling. In addition to liver, we also observed similar effects in mouse heart (data not shown). Multiple organ injuries (including liver and heart) due to endothelial inflammation are one of the main life threatening events during sepsis. LPS-induced arterial endothelial cell inflammation is also important for atherogenesis. Therefore, our findings may provide a novel mechanistic explanation of the pathogenesis of sepsis and atherosclerosis. Besides, other studies also suggest that Slit2 expression can be modulated by PDGF and HIV gp120 (13, 29). Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, our analysis of the microarray data (40) revealed that i.p. injection of LPS-induced significant downregulated Slit2 and Robo4 in the whole heart of mice, and that pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8) treatment induced significant downregulation of Slit2 and Robo4 in HUVEC. Taken together, our studies imply that Slit2 is an important inflammation regulator and may be widely regulated by inflammatory stimuli and cytokines.

In conclusion, our study has shown that Slit2-Robo4 represses LPS-induced endothelial inflammation. LPS and endotoxemia may enhance inflammation by downregulating Slit2 and Robo4 in endothelial cells. The anti-inflammatory effect of Slit2 is mediated through inhibition of cytokine/chemokine expression and monocyte adhesion. Furthermore, we have shown that Slit2-Robo4 suppresses LPS-induced signaling by inhibiting the activation of Pyk2 - NF-kB pathway. These suggest that Slit2-Robo4 signaling plays an important role in modulating endothelial inflammation and endotoxemia-induced organ injury. Therefore, Slit2 appears to be a promising candidate for developing novel therapies against sepsis-induced organ injury and atherosclerosis. In addition, serum Slit2 level could also be used as an indicator of vascular wall inflammation status.

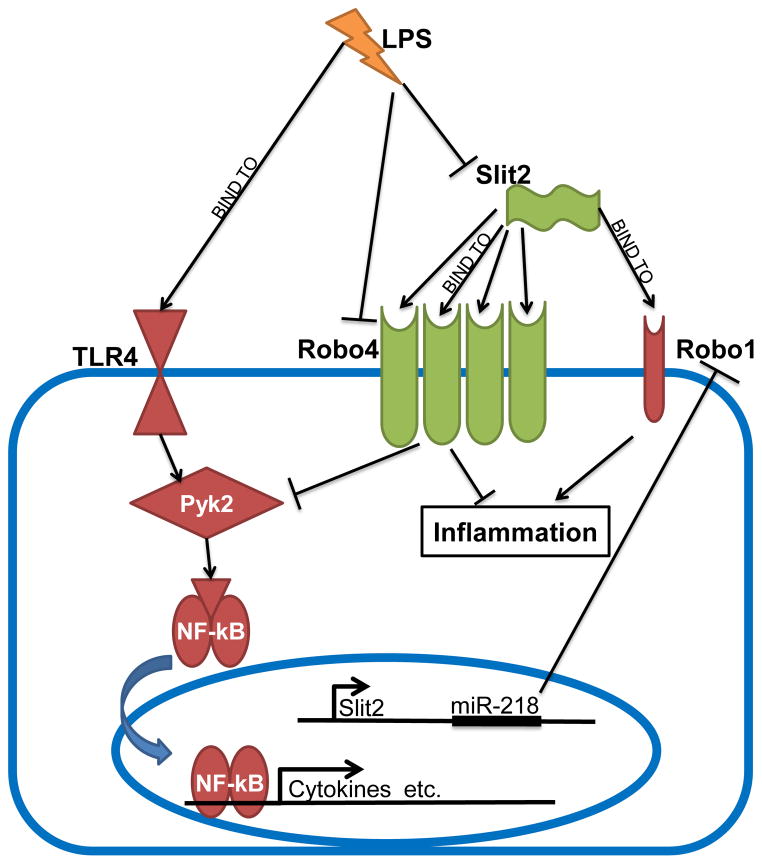

Figure 6. Proposed mechanism of Slit2 regulating LPS-induced endothelial inflammation and dysregulation of Slit2-Robo pathway by LPS.

Pro-inflammatory TLR4-Pyk2-NF-kB and Slit2-Robo1 pathways are labeled as red shapes, anti-inflammatory Slit2-Robo4 as green. Robo4 is dominantly expressed in endothelial cells, compared to Robo1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent program for providing the THP-1 cell line, thank Dr. James Waldman, Dr. Li Wu and Dr. Sujit Basu for valuable opinions and discussions about the research, thank Catherine Powell for help in animal study and thank Cory Gregory for experimental assistance.

This research is supported in part by NIH Grants R01 CA109527, R01 CA153490 and R21 AI091420 to R.K.G. and Pelotonia Graduate Fellowship to H.Z.

Abbreviations

- Slit2-N

N-terminal Slit2

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions

H.Z. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A.R.A. performed experiments, analyzed data. R.K.G. conceived the study, designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. Novel strategies for the treatment of sepsis. Nat Med. 2003;9:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nm0503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander C, Rietschel ET. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides and innate immunity. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:167–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hack CE, Zeerleder S. The endothelium in sepsis: source of and a target for inflammation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S21–27. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierhaus A, Chen J, Liliensiek B, Nawroth PP. LPS and cytokine-activated endothelium. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2000;26:571–587. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chedotal A. Slits and their receptors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;621:65–80. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandis AZ, Ganju RK. Slit: a roadblock for chemotaxis. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.91.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen Ba-Charvet KT, Brose K, Ma L, Wang KH, Marillat V, Sotelo C, Tessier-Lavigne M, Chedotal A. Diversity and specificity of actions of Slit2 proteolytic fragments in axon guidance. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4281–4289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04281.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg JM, Thompson FY, Brooks SK, Shannon JM, Akeson AL. Slit and robo expression in the developing mouse lung. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:350–360. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CA, London NR, Chen H, Park KW, Sauvaget D, Stockton RA, Wythe JD, Suh W, Larrieu-Lahargue F, Mukouyama YS, Lindblom P, Seth P, Frias A, Nishiya N, Ginsberg MH, Gerhardt H, Zhang K, Li DY. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nat Med. 2008;14:448–453. doi: 10.1038/nm1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheldon H, Andre M, Legg JA, Heal P, Herbert JM, Sainson R, Sharma AS, Kitajewski JK, Heath VL, Bicknell R. Active involvement of Robo1 and Robo4 in filopodia formation and endothelial cell motility mediated via WASP and other actin nucleation-promoting factors. FASEB J. 2009;23:513–522. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-098269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Yu J, Kuzontkoski PM, Zhu W, Li DY, Groopman JE. Slit2/Robo4 signaling modulates HIV-1 gp120-induced lymphatic hyperpermeability. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002461. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niclou SP, Jia L, Raper JA. Slit2 is a repellent for retinal ganglion cell axons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4962–4974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04962.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fish JE, Wythe JD, Xiao T, Bruneau BG, Stainier DY, Srivastava D, Woo S. A Slit/miR-218/Robo regulatory loop is required during heart tube formation in zebrafish. Development. 2011;138:1409–1419. doi: 10.1242/dev.060046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel S, Huang YW, Reheman A, Pluthero FG, Chaturvedi S, Mukovozov IM, Tole S, Liu GY, Li L, Durocher Y, Ni H, Kahr WH, Robinson LA. The cell motility modulator Slit2 is a potent inhibitor of platelet function. Circulation. 126:1385–1395. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dallol A, Da Silva NF, Viacava P, Minna JD, Bieche I, Maher ER, Latif F. SLIT2, a human homologue of the Drosophila Slit2 gene, has tumor suppressor activity and is frequently inactivated in lung and breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5874–5880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan H, Zu G, Xie Y, Tang H, Johnson M, Xu X, Kevil C, Xiong WC, Elmets C, Rao Y, Wu JY, Xu H. Neuronal repellent Slit2 inhibits dendritic cell migration and the development of immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;171:6519–6526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu D, Hou J, Hu X, Wang X, Xiao Y, Mou Y, De Leon H. Neuronal chemorepellent Slit2 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration by suppressing small GTPase Rac1 activation. Circ Res. 2006;98:480–489. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205764.85931.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones CA, Nishiya N, London NR, Zhu W, Sorensen LK, Chan AC, Lim CJ, Chen H, Zhang Q, Schultz PG, Hayallah AM, Thomas KR, Famulok M, Zhang K, Ginsberg MH, Li DY. Slit2-Robo4 signalling promotes vascular stability by blocking Arf6 activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1325–1331. doi: 10.1038/ncb1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye BQ, Geng ZH, Ma L, Geng JG. Slit2 regulates attractive eosinophil and repulsive neutrophil chemotaxis through differential srGAP1 expression during lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:6294–6305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand AR, Zhao H, Nagaraja T, Robinson LA, Ganju RK. N-terminal Slit2 inhibits HIV-1 replication by regulating the actin cytoskeleton. Retrovirology. 2013;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LJ, Zhao Y, Han B, Ma YG, Zhang J, Yang DM, Mao JW, Tang FT, Li WD, Yang Y, Wang R, Geng JG. Targeting Slit-Roundabout signaling inhibits tumor angiogenesis in chemical-induced squamous cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.London NR, Zhu W, Bozza FA, Smith MC, Greif DM, Sorensen LK, Chen L, Kaminoh Y, Chan AC, Passi SF, Day CW, Barnard DL, Zimmerman GA, Krasnow MA, Li DY. Targeting Robo4-dependent Slit signaling to survive the cytokine storm in sepsis and influenza. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:23ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, Geng JG. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by Slit-Robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking Robo activity. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narayan G, Goparaju C, Arias-Pulido H, Kaufmann AM, Schneider A, Durst M, Mansukhani M, Pothuri B, Murty VV. Promoter hypermethylation-mediated inactivation of multiple Slit-Robo pathway genes in cervical cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong R, Yu J, Pu H, Zhang Z, Xu X. Frequent SLIT2 promoter methylation in the serum of patients with ovarian cancer. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:681–686. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dallol A, Forgacs E, Martinez A, Sekido Y, Walker R, Kishida T, Rabbitts P, Maher ER, Minna JD, Latif F. Tumour specific promoter region methylation of the human homologue of the Drosophila Roundabout gene DUTT1 (ROBO1) in human cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:3020–3028. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ning Y, Sun Q, Dong Y, Xu W, Zhang W, Huang H, Li Q. Slit2-N inhibits PDGF-induced migration in rat airway smooth muscle cells: WASP and Arp2/3 involved. Toxicology. 2011;283:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Costinean S, Croce CM. MicroRNAs, the immune system and rheumatic disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:534–541. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alajez NM, Lenarduzzi M, Ito E, Hui AB, Shi W, Bruce J, Yue S, Huang SH, Xu W, Waldron J, O’Sullivan B, Liu FF. MiR-218 suppresses nasopharyngeal cancer progression through downregulation of survivin and the SLIT2-ROBO1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2381–2391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Small EM, Sutherland LB, Rajagopalan KN, Wang S, Olson EN. MicroRNA-218 regulates vascular patterning by modulation of Slit-Robo signaling. Circ Res. 2010;107:1336–1344. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prasad A, Qamri Z, Wu J, Ganju RK. Slit-2/Robo-1 modulates the CXCL12/CXCR4-induced chemotaxis of T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:465–476. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1106678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, Sega M, Agarwal A. “Lumen digestion” technique for isolation of aortic endothelial cells from heme oxygenase-1 knockout mice. Biotechniques. 2004;37:84–86. 88–89. doi: 10.2144/04371ST05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nasser MW, Qamri Z, Deol YS, Ravi J, Powell CA, Trikha P, Schwendener RA, Bai XF, Shilo K, Zou X, Leone G, Wolf R, Yuspa SH, Ganju RK. S100A7 enhances mammary tumorigenesis through upregulation of inflammatory pathways. Cancer Res. 72:604–615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anand AR, Bradley R, Ganju RK. LPS-induced MCP-1 expression in human microvascular endothelial cells is mediated by the tyrosine kinase, Pyk2 via the p38 MAPK/NF-kappaB-dependent pathway. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anand AR, Cucchiarini M, Terwilliger EF, Ganju RK. The tyrosine kinase Pyk2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-8 expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5636–5644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo SW, Zheng Y, Lu Y, Liu X, Geng JG. Slit2 Overexpression Results in Increased Microvessel Density and Lesion Size in Mice With Induced Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1933719112452940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tie J, Pan Y, Zhao L, Wu K, Liu J, Sun S, Guo X, Wang B, Gang Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Qiao T, Zhao Q, Nie Y, Fan D. MiR-218 inhibits invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by targeting the Robo1 receptor. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]