Abstract

Objectives

To examine prevalence of tobacco use and coexistence of cardiometabolic risk factors according to smoking status in youth with diabetes mellitus.

Study design

Youth aged 10 to 22 years who participated in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study (n = 3466) were surveyed about their tobacco use and examined for cardiometabolic risk factors: waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, physical activity, and lipid profile.

Results

The prevalence of tobacco use in youth aged 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and ≥20 years with type 1 diabetes mellitus was 2.7%, 17.1%, and 34.0%, respectively, and the prevalence in youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus was 5.5%, 16.4%, and 40.3%,respectively. Smoking was more likely in youth with annual family incomes <$50 000, regardless of diabetes mellitus type. Cigarette smoking was associated with higher odds of high triglyceride levels and physical inactivity in youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Less than 50% of youth aged 10 to 14 years (52.2% of participants) reported having ever been counseled by their healthcare provider to not smoke or to stop smoking.

Conclusions

Tobacco use is prevalent in youth with diabetes mellitus. Aggressive tobacco prevention and cessation programs should be a high priority to prevent or delay the development of cardiovascular disease.

The adverse health effects of tobacco use are well documented. Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and is a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.1 The risk of the development of cardiovascular disease is greatly increased in adults with diabetes mellitus compared with adults without diabetes mellitus, and smoking may increase that risk.2–4 Several studies have documented that smoking increases the risk of premature mortality and microvascular and macrovascular complications in adults with diabetes mellitus.2,5–7

Data from the national Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) show that the prevalence of smoking in young adults with diabetes mellitus is similar to the prevalence in the general population.8 Recent reports suggest that the prevalence of tobacco use remains stable at levels higher than the national Healthy People 2010 goals and may be increasing in teenagers and young adults.9–11 Tobacco use is particularly risky for youth with chronic conditions because their health is already compromised. Additionally, the younger people begin to smoke, the more likely they are to smoke as adults. Approximately 90% of adult smokers report having started smoking before 18 years of age.12 Because of the already increased risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with diabetes mellitus, the American Diabetes Association emphasizes the importance of smoking cessation in people with diabetes mellitus.13

Few studies have examined the prevalence of tobacco use or the cardiometabolic risk factors associated with smoking in youth with diabetes mellitus, information that is critical for targeting prevention efforts. The objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of tobacco use and to examine the co-existence of cardiometabolic risk factors according to cigarette smoking status in youth with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) is a multi-center study that began conducting population-based ascertainment of all existing (prevalent) cases of non-gestational clinically diagnosed diabetes mellitus in youth <20 years of age in calendar year 2001 and all newly diagnosed (incident) cases during subsequent years.14 In brief, youth with clinically diagnosed diabetes mellitus were identified: (1) in geographically defined populations in Ohio, Colorado, Washington, and South Carolina; (2) in managed healthcare plan enrollees in Hawaii (Hawaii Medical Service Association, Med-Quest, and Kaiser Permanente) and southern California (Kaiser Permanente); and (3) in Indian Health Service beneficiaries in 4 American Indian populations. A diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was validated when any of these criteria were met: (1) medical record review indicated a healthcare provider diagnosis of diabetes mellitus; (2) the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was directly verified by a healthcare provider; (3) the healthcare provider referred a youth with diabetes mellitus to the study; or (4) the case was included in a clinical database that had a requirement for verification of diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by a healthcare provider. Participants’ type of diabetes mellitus was based on clinical diagnosis made by their healthcare provider. Local institutional review boards with jurisdiction over local study populations approved the study.

Following Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant procedures, youth with diabetes mellitus or their parent/guardian were asked to complete an initial survey that collected information on race/ethnicity and diabetes-related factors. Race and ethnicity were collected with 2000 US Census questions. Youth who replied to the survey and whose diabetes mellitus was not caused by other conditions were invited to an in-person study visit. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the study visit from participants aged ≥18 years and from the parent/guardian of participants aged ≤17 years according to the guidelines established by the local institutional review board. All study personnel were trained in study procedures before initiation of data collection and were re-certified annually. All surveys were available in English and Spanish.

During the study visit, research staff conducted physical examinations that included height, weight, waist circumference, and measurement of blood pressure. Body weight and height were measured in light indoor clothing without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 centimeter with the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) protocol.15 Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured and recorded twice and averaged. Three blood pressure measurements were obtained after the participant had been seated quietly for 5 minutes. Blood pressure was measured with a standard mercury sphygmomanometer with 1 of 5 cuff sizes chosen on the basis of the circumference of the participant’s arm. The average of the 3 blood pressure measurements was used in analyses.

Overnight fasting blood samples were drawn from metabolically stable participants for measurement of hemoglobin A1c, glucose, and lipid levels. Blood specimens were processed locally and shipped to a central laboratory (Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories, Seattle, Washington). Specific laboratory methods have been de-scribed.14 In brief, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels were analyzed enzymatically with commercially available reagents. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels were calculated with the Friede-wald equation for participants who had triglyceride levels <400 mg/dL and by Lipid Research Clinics Beta Quantification for participants with triglyceride levels ≥400 mg/dL.16,17 Glycemic control was categorized with age-specific A1c levels on the basis of American Diabetes Association guidelines as good (<8.5%, <8.0%, <7.5%, <7.0% for ages <6, 6–12, 13–18, and ≥ 19 years, respectively), intermediate (8.5%–9.5%, 8.0%–9.5%, 7.5%–9.5%, 7.0%–9.5% for <6, 6– 12, 13–18, and ≥ 19 years, respectively), and poor (>9.5% for all age groups).18

Survey information including demographic characteristics, medical history, medications, healthcare use, perceptions of care, and family history was collected at the study visit. Family history of diabetes mellitus was defined as having a biological sibling, parent, or grandparent with diabetes mellitus. Information about physical activity, smoking, tobacco use, and other health behaviors was also collected. Participant interviews and questionnaires were completed in a confidential manner. Responses were not shared with the participant’s parent or guardian.

Smoking, tobacco use, and physical activity questions were derived from the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey.19 Information on smoking and tobacco use focused on recent tobacco use and smoking and tobacco use history. Current tobacco use was defined as use of any cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, little cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. Current cigarette smoking was defined as having smoked cigarettes on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. Similar definitions were used for current smokeless tobacco (chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip) and cigar use. Individuals who had tried smoking or smoked regularly (at least one cigarette every day for 30 days) but were not current smokers were considered past smokers. Youth who had never smoked a whole cigarette were considered non-smokers. Participants were also asked whether their healthcare provider or another healthcare provider asked whether they smoked or used tobacco. Additionally, they were asked whether their doctor or nurse had ever counseled them to not smoke or to stop smoking. Participants were also asked the average number of days in a typical week that they participated in physical activity for at least 20 minutes that made them sweat or breathe hard and were then categorized as physically inactive (0–2 days/week) or physically active (3–7 days/week).

Cardiometabolic risk factors were defined as abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥90th percentile for age and sex),20 elevated blood pressure (systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥95th percentile for age, height, and sex),21 physical inactivity (physically active 0–2 days per week), high triglyceride level (≥110 mg/dL), high LDL cholesterol level (≥100 mg/dL), and low HDL cholesterol level (≤40 mg/dL).22

Statistical Analysis

Of the 3505 participants aged ≥10 years who completed a study visit and whose diabetes mellitus was prevalent in 2001 or incident in 2002 to 2005, 35 were excluded for having a diabetes mellitus type other than type 1 or type 2, and an additional 4 participants were excluded for missing information on having ever tried smoking, leaving 3466 youth with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus for the assessment of prevalence of tobacco use and healthcare provider counseling on tobacco use. For the cardiometabolic risk factor analyses, an additional 457 participants were excluded sequentially because of missing responses to the physical activity questions (n = 4) or missing laboratory tests (n = 282) or anthropometric (n = 171) measures.Therefore, 3009 youth with type1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus were included in the analyses examining the association between smoking and cardiometabolic risk factors.

Characteristics of the study population were compared across smoking status categories, stratified by diabetes type. Analysis of variance was used to assess differences in continuous variables, and χ2 analyses were used for categorical variables. For the analysis of variance tests, distributions of the residuals were checked for normality assumptions; log transformed values were used in the testing procedure for diabetes duration, waist circumference, and triglycerides. Prevalence of smoking and tobacco use was calculated and stratified according to diabetes type and demographic characteristics (sex, age, race/ethnicity). Multiple logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs for the associations between cigarette smoking and cardiometabolic risk factors. Initial models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and glycemic control. Subsequent models included BMI z-score. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Of the 3466 youth with type 1 (n = 2887) or type 2 (n = 579) diabetes mellitus who completed the SEARCH in-person visit and had complete smoking and tobacco use information, 22.0% with type 1 diabetes mellitus reported having ever tried smoking cigarettes (even one or two puffs in their lifetime) and 35.9% with type 2 diabetes mellitus reported having ever tried smoking. Approximately 10% of youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 15.7% with type 2 diabetes mellitus reported current use of some form of tobacco product (Table I). The prevalence of current cigarette and cigar smoking was higher in youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus (13.1% for cigarettes and 6.2% for cigars) than youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus (8.1% for cigarettes and 2.9% for cigars), and smokeless tobacco use was similar. In youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, cigarette use was more common than cigar smoking or using smokeless tobacco, and use of any tobacco product increased with increasing age. American Indian youth had the highest prevalence of tobacco use, and Asian/Pacific Islander youth had the lowest. Tobacco use was more prevalent in youth with family annual incomes <$50 000.

Table I.

Characteristics and prevalence of current tobacco use, including cigarettes, cigars, or smokeless tobacco, in youth who ever tried smoking by diabetes mellitus type

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Any tobacco product |

Cigarettes | Cigars | Smokeless tobacco |

Total | Any tobacco product |

Cigarettes | Cigars | Smokeless tobacco |

|

| n (%)* | n (%)† | n (%)‡ | n (%)§ | n (%)¶ | n (%)* | n (%)† | n (%)‡ | n (%)§ | n (%)¶ | |

| Total | 2887 (100.0) | 286 (9.9) | 233 (8.1) | 84 (2.9) | 41 (1.4) | 579 (100.0) | 89 (15.7) | 74 (13.1) | 34 (6.2) | 10 (1.8) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 1451 (50.3) | 160 (11.0) | 120 (8.3) | 60 (4.1) | 32 (2.2) | 214 (37.0) | 38 (18.3) | 30 (14.4) | 17 (8.3) | 5 (2.4) |

| Female | 1436 (49.7) | 126 (8.8) | 113 (7.9) | 24 (1.7) | 9 (0.6) | 365 (63.0) | 51 (14.3) | 44 (12.3) | 17 (5.0) | 5 (1.5) |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 10–14 | 1628 (56.4) | 39 (2.4) | 21 (1.3) | 17 (1.0) | 12 (0.7) | 184 (31.8) | 10 (5.5) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) |

| 15–19 | 1055 (36.5) | 182 (17.3) | 157 (14.9) | 50 (4.7) | 23 (2.2) | 326 (56.3) | 52 (16.4) | 41 (12.9) | 22 (7.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| ≥20 | 204 (7.1) | 65 (31.9) | 55 (27.0) | 17 (8.3) | 6 (2.9) | 69 (11.9) | 27 (40.3) | 25 (37.3) | 10 (14.9) | 3 (4.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2144 (74.3) | 232 (10.8) | 189 (8.8) | 62 (2.9) | 40 (1.9) | 104 (18.0) | 21 (20.2) | 20 (19.2) | 5 (4.8) | 4 (3.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 214 (7.4) | 15 (7.0) | 11 (5.1) | 8 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 182 (31.4) | 24 (13.2) | 18 (9.9) | 11 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic | 353 (12.2) | 28 (7.9) | 24 (6.8) | 11 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 120 (20.7) | 13 (10.8) | 11 (9.2) | 8 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 54 (1.9) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (7.9) | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| American Indian | 21 (0.7) | 4 (19.1) | 4 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 111 (19.2) | 26 (26.5) | 20 (20.4) | 9 (11.4) | 6 (7.5) |

| Other | 101 (3.5) | 5 (5.0) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.8) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Household income | ||||||||||

| <$25k | 349 (12.2) | 37 (10.6) | 32 (9.2) | 10 (2.9) | 2 (0.6) | 208 (38.0) | 38 (18.3) | 32 (15.4) | 9 (4.3) | 4 (1.9) |

| $25–49k | 579 (20.2) | 72 (12.4) | 57 (9.9) | 24 (4.2) | 12 (2.1) | 133 (24.3) | 20 (15.0) | 17 (12.8) | 13 (9.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| $50–75k | 592 (20.6) | 42 (7.1) | 36 (6.1) | 10 (1.7) | 8 (1.4) | 57 (10.4) | 12 (21.1) | 11 (19.3) | 5 (8.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| ≥$75k | 1109 (38.6) | 81 (7.3) | 58 (5.2) | 27 (2.4) | 16 (1.4) | 52 (9.5) | 4 (7.7) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.8) | 1 (1.9) |

| Don’t know/refused | 242 (8.4) | 53 (21.9) | 49 (20.4) | 13 (5.4) | 3 (1.2) | 97 (17.7) | 14 (14.4) | 13 (13.4) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (2.1) |

Column percentage.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus n = 2887; type 2 diabetes mellitus n = 566.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus n = 2883; type 2 diabetes mellitus n = 566.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus n = 2886; type 2 diabetes mellitus n = 547.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus n = 2886; type 2 diabetes mellitus n = 548.

The prevalence of reporting having ever been asked by their healthcare provider whether they smoked or used tobacco products increased with age in youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus, from 30.4% in 10- to 14-year-old participants to 68.3% in 15- to 19-year-old participants and 84.7% in youth ≥20 years of age (P < .0001; data not shown). Only 47.2%, 51.8%, and 57.4% of youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus aged 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and ≥20 years, re-spectively, reported having ever been counseled by their healthcare provider to not smoke or to stop smoking (P for trend = .005). Similarly for type 2 diabetes mellitus, 40.7%, 67.3%, and 79.7% of youth aged 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and ≥20 years, respectively, reported having ever been asked by their healthcare provider whether they smoked or used tobacco products (P for trend < .0001). However, in youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus, there were no differences in the age groups for reporting having ever been counseled by their healthcare provider to not smoke or to stop smoking (47.2%, 52.3%, and 47.8% in ages 10–14 years, 15–19 years, and ≥20 years, respectively; P = .51).

In youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus, current smokers were older, had a longer duration of diabetes, were more likely to be physically inactive and have poor glycemic control, and had lower household incomes than non-smokers (Table II). Mean waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, LDL cholesterol level, triglyceride level, and A1c level were higher and mean HDL cholesterol level was lower in current smokers than non-smokers. In youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus, current smokers were older, had a longer duration of diabetes, and were more likely have poor glycemic control than non-smokers. Mean waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, triglyceride level, and A1c level were higher and mean HDL cholesterol level was lower in current smokers than non-smokers with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Table II.

Characteristics of youth with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus by cigarette smoking status

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

Type 2 diabetes mell itus |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking status |

Cigarette smoking status |

|||||||||

| Characteristic | Total (n = 2536) |

Non- smoker (n = 2124) |

Past smoker (n = 209) |

Current smoker (n = 203) |

P value* |

Total (n = 473) |

Non- smoker (n = 348) |

Past smoker (n = 59) |

Current smoker (n = 66) |

P value* |

| Age, years | 14.8 (3.1) | 14.2 (2.8) | 17.7 (2.7) | 18.3 (2.2) | <.0001 | 16.3 (3.1) | 15.6 (2.6) | 17.9 (2.4) | 18.6 (2.5) | <.0001 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 9.8 (4.0) | 9.7 (3.9) | 10.7 (4.4) | 10.6 (4.3) | <.0001 | 13.9 (4.0) | 13.4 (2.4) | 15.0 (2.1) | 15.3 (2.1) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes duration, months† | 54.4 (50.9) | 48.8 (47.0) | 79.5 (59.4) | 87.0 (60.3) | <.0001 | 25.0 (48.8) | 22.0 (20.9) | 31.6 (24.2) | 35.0 (23.9) | <.0001 |

| Male, % | 50.2 | 50.5 | 47.4 | 50.7 | .6856 | 37.6 | 35.6 | 47.5 | 39.4 | .2115 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | .2035 | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 76.1 | 75.6 | 75.6 | 81.3 | 20.7 | 19.3 | 23.7 | 25.8 | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.0 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 33.4 | 36.2 | 25.4 | 25.8 | ||

| Hispanic | 11.2 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 9.9 | 21.1 | 23.6 | 15.3 | 13.6 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 1.7 | 3.0 | ||

| American Indian | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 14.8 | 9.8 | 28.8 | 28.8 | ||

| Other | 3.3 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 3.0 | ||

| Household income, % | <.0001 | .4999 | ||||||||

| <$25k | 12.1 | 11.5 | 16.8 | 13.9 | 39.7 | 37.9 | 44.1 | 45.5 | ||

| $25–49k | 20.1 | 19.8 | 16.8 | 26.2 | 24.6 | 24.9 | 22.0 | 25.8 | ||

| $50–75k | 21.2 | 22.2 | 16.4 | 15.8 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 13.6 | ||

| ≥$75k | 38.9 | 40.4 | 37.0 | 25.3 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 1.5 | ||

| Don’t know/refused | 7.7 | 6.1 | 13.0 | 18.8 | 15.9 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 13.6 | ||

| Waist circumference, cm† | 79.3 (12.1) | 78.1 (11.9) | 84.1 (10.8) | 86.4 (11.0) | <.0001 | 109.5 (18.0) | 107.9 (19.3) | 109.8 (17.3) | 117.6 (37.2) | .0198 |

| BMI z score | 0.62 (0.89) | 0.62 (0.89) | 0.61 (0.88) | 0.64 (0.92) | .9310 | 1.98 (1.01) | 2.02 (0.72) | 1.77 (1.15) | 1.94 (0.73) | .0855 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 106.4 (11.0) | 105.6 (10.9) | 109.8 (10.6) | 110.7 (10.9) | <.0001 | 117.1 (11.9) | 116.4 (12.9) | 117.2 (11.3) | 120.8 (11.8) | .0349 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 67.6 (9.7) | 66.9 (9.6) | 71.2 (9.7) | 71.1 (9.8) | <.0001 | 72.8 (10.1) | 72.2 (10.8) | 74.2 (10.2) | 74.8 (10.2) | .1126 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 53.5 (12.6) | 53.8 (12.5) | 53.0 (13.7) | 51.2 (12.8) | .0209 | 42.1 (13.0) | 42.6 (10.7) | 40.2 (10.6) | 40.9 (11.1) | .1847 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 98.6 (27.8) | 97.2 (26.9) | 107.1 (31.0) | 105.0 (31.8) | <.0001 | 106.0 (28.8) | 104.5 (31.6) | 107.6 (33.6) | 112.3 (37.2) | .1964 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL† | 88.4 (107.8) | 83.0 (106.0) | 104.8 (85.0) | 127.2 (135.4) | <.0001 | 184.7 (150.8) | 169.1 (268.3) | 229.6 (277.2) | 226.9 (291.1) | .0044 |

| Physical activity, % | .0025 | .0824 | ||||||||

| <3 days/week | 39.8 | 38.3 | 46.4 | 48.3 | 49.5 | 47.1 | 49.2 | 62.1 | ||

| ≥3 days/week | 60.2 | 61.7 | 53.6 | 51.7 | 50.5 | 52.9 | 50.8 | 37.9 | ||

| A1c | 8.32 (1.74) | 8.19 (1.63) | 8.89 (2.07) | 9.16 (2.08) | <.0001 | 7.98 (2.54) | 7.77 (2.37) | 8.23 (2.89) | 8.85 (2.89) | .0049 |

| Glycemic control, %‡ | <.0001 | .0481 | ||||||||

| Good | 36.6 | 40.3 | 19.7 | 14.8 | 53.8 | 57.6 | 47.5 | 39.4 | ||

| Intermediate | 43.5 | 42.4 | 48.6 | 49.8 | 20.3 | 19.3 | 23.7 | 22.7 | ||

| Poor | 20.0 | 17.3 | 31.7 | 35.5 | 25.9 | 23.1 | 28.8 | 37.9 | ||

| Family Hx of diabetes, %§ | 59.7 | 59.7 | 59.3 | 60.6 | 0.9614 | 88.2 | 88.0 | 89.8 | 87.7 | .9147 |

Data are means (SD) or percentage.

BP, blood pressure; Hx, history.

P value for categorical variables with χ2 test for the association between variable levels and smoking status and for continuous variables with analysis of variance.

P values are based on log-transformed values.

Glycemic control is defined according to age-specific A1c levels based on American Diabetes Association guidelines (good = <8.5%, <8.0%, <7.5%, <7.0% for ages <6 years, 6–12 years, 13–18 years, and ≥19 years, respectively; intermediate = 8.5%–9.5%, 8.0%–9.5%, 7.5%–9.5%, 7.0%–9.5% for <6 years, 6–12 years, 13–18 years, and ≥19 years, respectively; poor = >9.5% for all age groups).

Family history includes parents, grandparents, and biological siblings.

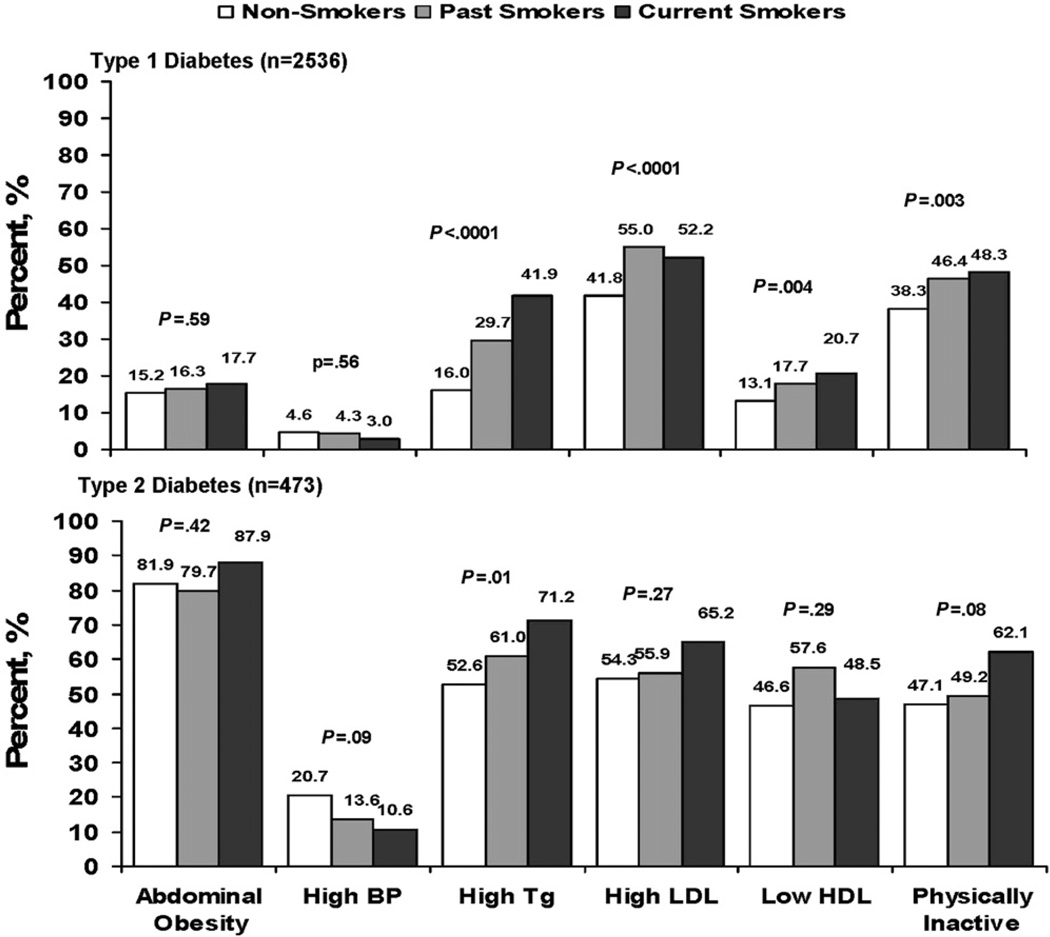

Past and current smokers with type 1 diabetes mellitus had a higher prevalence of high triglyceride level, high LDL cholesterol level, low HDL cholesterol level, and physical inactivity than non-smokers. Abdominal obesity and high blood pressure were similar among non-smokers, past smokers, and current smokers (Figure 1). Similar associations were found among past smokers and current smokers with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but because of the small number of cigarette smokers in this group and the overall small sample size, results did not reach statistical significance, with the exception of high triglyceride level.

Figure 1.

Presence of the individual cardiometabolic risk factors by cigarette smoking status in youth with diabetes mellitus (P value from χ2 test for the association between cardiometabolic risk factor and smoking status).

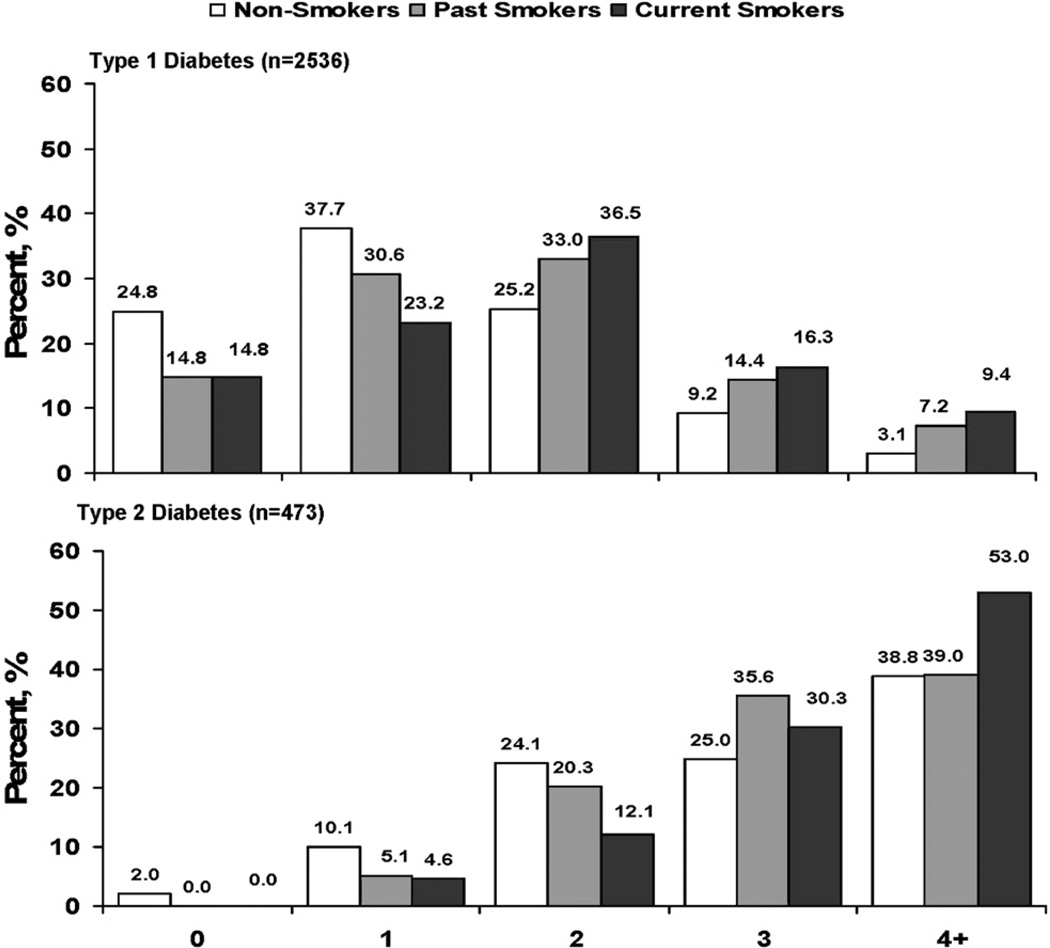

Past and current smokers had a less favorable cardiometabolic risk profile than non-smokers. In youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus, 24.8% of non-smokers, 14.8% of past smokers, and 14.8% of current smokers had no risk factors, and 3.1%, 7.2%, and 9.4%, respectively, had ≥4 risk factors (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com). In youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus, only 2.0% of non-smokers and no past and current smokers had no risk factors, and 38.3% of non-smokers, 39.0% of past smokers, and 53.0% of current smokers had ≥4 risk factors.

Figure 2.

Distribution of additional cardiometabolic risk factors by cigarette smoking status in youth with diabetes mellitus. Risk factors include abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure, low HDL-cholesterol level, high triglyceride level, high LDL-cholesterol level, and physically inactivity.

After adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and glycemic control, youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus who were current smokers had higher odds of high triglyceride level and physical inactivity compared with non-smokers (Table III). Past smokers had a 44% higher odds of high LDL cholesterol level compared with non-smokers. Results were similar after additional adjustment for BMI-z score. Odds ratio estimates for cardiometabolic risk factors in participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus were in the same direction as in youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus, with the exception of low HDL cholesterol level.

Table III.

Odds ratios (95% CI) of cardiometabolic risk factors according to smoking status among youth with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus n = 2536 |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus n = 473 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | Past smoker* (n = 209) Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

Current smoker* (n = 203) Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

Past smoker* (n = 59) Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

Current smoker* (n = 66) Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

| Abdominal obesity | 1.12 (0.73–1.72) | 1.35 (0.88–2.07) | 1.10 (0.51–2.37) | 1.94 (0.81–4.67) |

| High blood pressure | 0.77 (0.35–1.69) | 0.58 (0.24–1.44) | 0.70 (0.30–1.64) | 0.56 (0.23–1.37) |

| High triglycerides | 1.14 (0.80–1.64) | 1.88 (1.33–2.67)‡ | 1.03 (0.54–1.97) | 1.35 (0.69–2.65) |

| High LDL cholesterol | 1.44 (1.05–1.98)§ | 1.16 (0.84–1.62) | 1.08 (0.58–2.01) | 1.46 (0.78–2.74) |

| Low HDL cholesterol | 1.09 (0.72–1.64) | 1.26 (0.84–1.90) | 1.40 (0.76–2.60) | 0.97 (0.53–1.80) |

| Physically inactive | 1.27 (0.93–1.73) | 1.41 (1.02–1.94)§ | 1.10 (0.60–2.01) | 1.68 (0.91–3.10) |

Reference is non-smokers (n = 2124 for type 1 diabetes mellitus; n = 348 for type 2 diabetes mellitus).

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and A1c.

P value <.001.

P value <.05.

Discussion

The results from this study, conducted in a large, racially and ethnically diverse cohort of youth with diabetes mellitus, demonstrate that a substantial proportion of youth with diabetes are current users of tobacco products, adding to their already elevated risk for cardiovascular disease associated with having diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, the proportions of youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus reporting having ever been asked by their healthcare provider whether they smoked or used tobacco products and having ever been counseled to not smoke or to stop smoking were low. This study also found that youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus who were current smokers were more likely to have high triglyceride levels and to be physically inactive. Similar associations were found in youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus, although the results were not statistically significant because of the smaller sample size overall for youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Estimates from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that 25.7% of high school youth in 2007 reported current tobacco use (cigarette smoking, smokeless tobacco, or cigar use); 20% were current cigarette smokers (had smoked on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey), 7.9% were current users of smokeless tobacco, and 13.6% were current users of cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars.23 In 2006, the National Youth Tobacco Survey found that 9.5% of middle school students reported current use of tobacco products; 6.3% were current cigarette smokers, 4.0% were current cigar users, 2.6% were current users of smokeless tobacco, and 2.2%, 1.7%, and 1.4% were current users of pipes, bidis, and clove cigarettes, respectively.11 Our estimates of smoking behaviors in youth with diabetes mellitus collected from 2002 to 2005 are lower than these national estimates, but are similar to national data from NHANES (1999–2004), which show that 13% of youth aged 12 to 17 years in the United States were current cigarette smokers.24

Few studies have examined the association between cigarette smoking and cardiometabolic risk factors in youth with diabetes mellitus. In a small study of 165 youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus, smokers had higher total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, A1c, fructosamine, apolipoprotein B, and serum P-selectin levels than non-smokers.25 In a study of 27 561 patients aged 15 to 20 years with type 1 diabetes mellitus from 247 medical centers in Austria and Germany, Hofer et al found that self-reported cigarette smoking, defined as smoking one or more cigarettes per day, was common (21.6% of male and 13.7% of female participants) and that patients who were smokers had a worse cardiovascular risk profile than non-smokers.26 Smokers had higher A1c, triglyceride, and total cholesterol levels and diastolic blood pressure and lower systolic blood pressure and levels of HDL cholesterol compared with non-smokers.26 This suggests that youth who smoke may also take poorer care of their health.

These analyses have some limitations. First, this investigation used a cross-sectional design, and thus the temporal relationship between tobacco use and cardiometabolic risk factors cannot be established. Second, the study used self-reported health behaviors including physical activity and tobacco use, and participants may have over- or under-reported their physical activity or under-reported or denied their smoking behavior. Self-reported tobacco use has been validated in some studies,27 but in other studies smokers have been shown to deny their smoking.28 Additionally, any potential misclassification of smoking status is likely non-differential and would have only underestimated the true associations between cigarette smoking and cardiometabolic risk factors. Both physical activity and tobacco use questions were derived from validated questionnaires, which show good test-retest reliability.29 Third, we did not collect information on the quantity of cigarettes smoked. Therefore, we are unable to assess any dose-response relationship. Fourth, this study relied on youth self-report of tobacco use screening and counseling by their healthcare provider. We cannot determine the extent to which youth failed to remember screening and counseling. Finally, youth who were older, had type 2 diabetes mellitus, and were African-American were less likely to participate in the study visit.30 However, the SEARCH study provides information on a large, diverse contemporary sample of youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus that includes measures of key cardiometabolic risk factors and information on behaviors including smoking and physical activity.

Although smoking cessation has been shown to be an efficacious and cost-effective intervention, this study and others have shown that the proportion of patients asked about use of tobacco products and offered cessation advice by their healthcare providers is low.2,31,32 In this study, only 30.4% of youth aged 10 to 14 years with type 1 diabetes mellitus (representing 56.4% of the study participants with type 1 diabetes mellitus) reported having ever been asked whether they smoked or used tobacco products and only 47.2% reported having ever been counseled about smoking. In youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus aged 10 to 14 years (representing 31.8% of the study participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus), only 40.7% reported having ever been asked whether they smoked or used tobacco products and only 47.2% reported having ever been counseled about smoking. Although the proportion of participants reporting being asked about their use of tobacco products increased with increasing age, earlier research has also shown that the younger people begin to smoke the more likely they are to smoke as adults, indicating that counseling must begin at an early age.12 Data from the National Health Interview Surveys found that physician counseling to quit smoking increased from 35.1% in 1974 to 58.4% in 1990 in individuals with diabetes mellitus; however, >40% of individuals with diabetes mellitus who smoke did not receive any advice.32 Alfano et al found that 43.4% of adolescents reported being asked about use of cigarettes, 42.1% reported receiving counseling, and 28.8% reported both in their sample of 5016 adolescents (ages 16–19 years).31 Smoking cessation should be an important component of clinical diabetes care. Further efforts that focus on clinical interventions that facilitate the identification and counseling of adolescents and young adults with diabetes mellitus who use tobacco products are warranted.

In conclusion, this study supports evidence that the prevalence of several cardiometabolic risk factors is higher in current smokers than non-smokers. Additionally, this study demonstrates that the prevalence of tobacco use in youth with diabetes mellitus varies by tobacco product, sex, race/ethnicity, and age. Smoking is an avoidable risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease. Because of the high prevalence of tobacco use, the impact of smoking on cardiometabolic risk factors and the already increased risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with diabetes mellitus, youth with diabetes, regardless of type, should be targeted for aggressive smoking prevention and cessation programs.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- BMI

Body mass index

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- SEARCH

SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth;

Footnotes

Funding support and conflict of interest information is available at www.jpeds.com (Appendix).

Preliminary results of this study were presented at the 68th Annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Jun 6-10, 2008, San Francisco, CA.

The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study is indebted to the many youth and their families and their healthcare providers whose participation made this study possible.

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362:847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1887–1898. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Diabetes Care. 1979;2:120–126. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moy CS, LaPorte RE, Dorman JS, Songer TJ, Orchard TJ, Kuller LH, et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus mortality. The risk of cigarette smoking. Circulation. 1990;82:37–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muhlhauser I, Bender R, Bott U, Jorgens V, Grusser M, Wagener W, et al. Cigarette smoking and progression of retinopathy and nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 1996;13:536–543. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199606)13:6<536::AID-DIA110>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suarez L, Barrett-Connor E. Interaction between cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus in the prediction of death attributed to cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:670–675. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Gregg EW. Trends in cigarette smoking among US adults with diabetes: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Prev Med. 2004;39:1238–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S. Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group. Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet. 2006;367:749–753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cigarette use among high school students—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:686–688. 1991–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Jul 9, 2009];National Youth Tobacco Survey and Key Prevalence Indicators. 2006 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/pdfs/indicators.pdf.

- 12.Tyc VL, Throckmorton-Belzer L. Smoking rates and the state of smoking interventions for children and adolescents with chronic illness. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e471–e487. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL. American Diabetes Association. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl. 1):S74–S75. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth: a multicenter study of the prevalence, incidence and classification of diabetes mellitus in youth. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III 1988-94) reference manuals and reports (CD ROM) Bethesda, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hainline A, Jr, Miller DT, Mather A. The Coronary Drug Project. Role and methods of the central laboratory. Control Clin Trials. 1983;4:377–387. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(83)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes (position statement) Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl. 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Grunbaum JA, Whalen L, Eaton D, et al. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez JR, Redden DT, Pietrobelli A, Allison DB. Waist circumference percentiles in nationally representative samples of African-American, European-American, and Mexican-American children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2004;145:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl. 4th Report):555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811–822. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fryar C, Merino M, Hirsch R, Porter K. Smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use reported by adolescents aged 12–17 years: United States, 1999–2004. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. Report no.15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwab KO, Doerfer J, Hallermann K, Krebs A, Schorb E, Krebs K, et al. Marked smoking-associated increase of cardiovascular risk in childhood type 1 diabetes. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20:285–292. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofer SE, Rosenbauer J, Grulich-Henn J, Naeke A, Frohlich-Reiterer E, Holl RW. Smoking and metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2009;154:20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ismail AA, Gill GV, Lawton K, Houghton GM, MacFarlane IA. Comparison of questionnaire, breath carbon monoxide and urine cotinine in assessing the smoking habits of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2000;17:119–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holl RW, Grabert M, Heinze E, Debatin KM. Objective assessment of smoking habits by urinary cotinine measurement in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Reliability of reported cigarette consumption and relationship to urinary albumin excretion. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:787–791. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liese AD, Liu L, Davis C, Standiford D, Waitzfelder B, Dabelea D, et al. Participation in pediatric epidemiologic research: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfano CM, Zbikowski SM, Robinson LA, Klesges RC, Scarinci IC. Adolescent reports of physician counseling for smoking. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E47. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malarcher AM, Ford ES, Nelson DE, Chrismon JH, Mowery P, Merritt RK, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking and physicians’ advice to quit smoking among people with diabetes in the US. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:694–697. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.