Abstract

Tuberculosis is considered to be one of the world’s deadliest disease with 2 million deaths each year. The need for new antitubercular drugs is further exacerbated by the emergence of drug-resistance strains. Despite multiple recent efforts, the majority of the hits discovered by traditional target-based screening showed low efficiency in vivo. Therefore, there is heightened demand for whole-cell based approaches directly using host-pathogen systems. The phenotypic host-pathogen assay described here is based on the monitoring of GFP-expressing Mycobacterium marinum during infection of the amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii. The assay showed straight-forward medium-throughput scalability, robustness and ease of manipulation, demonstrating its qualities as an efficient compound screening system. Validation with a series of known antitubercular compounds highlighted the advantages of the assay in comparison to previously published macrophage-Mycobacterium tuberculosis-based screening systems. Combination with secondary growth assays based on either GFP-expressing D. discoideum or M. marinum allowed us to further fine-tune compound characterization by distinguishing and quantifying growth inhibition, cytotoxic properties and antibiotic activities of the compounds. The simple and relatively low cost system described here is most suitable to detect anti-infective compounds, whether they present antibiotic activities or not, in which case they might exert anti-virulence or host defense boosting activities, both of which are largely overlooked by classical screening approaches.

Introduction

Tuberculosis, a Serious Health Threat

The negative impact that tuberculosis (TB) has on human health is hard to overestimate. Over one third of the world population is infected by bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. Each year two million TB-related deaths are registered with 8 million newly infected people [1]. Despite the efforts of modern therapeutics, in nine of ten cases, Mtb manages to persist throughout the lifetime causing the risk of reinfection and reescalation of the disease [2].

The hallmark of TB is the formation of granuloma, well-organized multicellular structures primarily composed of mature macrophages and T-lymphocytes. Macrophages often develop into multinucleated giant cells and epitheloid cells. Granulomas also contain dendritic cells, neutrophils, NK-cells, fibroblasts and B-lymphocytes and are surrounded by a fibrous cuff. In addition, epithelial cells surrounding granulomas are proposed to participate in its formation. It is generally assumed that the granuloma is a host-defensive structure that sequesters and eradicates pathogenic bacteria. Although there is evidence of healed and often sterile granuloma among certain TB patients, recent findings indicated that Mtb employs a distinct mechanism of proliferation via granulomas [22]. Mtb mostly replicates in alveolar macrophages but can also be found in dendritic cells, adipocytes and type II alveolar pneumocytes [3]–[6].

Pathogenic mycobacteria, such as Mtb and other mycobacteria of the tuberculosis complex, but also Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium avium are able to manipulate a variety of processes including membrane trafficking [3], [7], autophagy [8], [9], signaling [10] and apoptosis [11], [12]. These manipulations of its host allow the bacteria to hijack the phagosome and prevent major steps of its maturation by performing rapid exclusion of the vacuolar H-ATPases [13], inhibiting the action of signalling lipids [14], [15] and proteins [16], [17] involved in phagosome maturation.

In order to find a way to counteract TB infection, considerable research efforts focus on a mechanistic study of mycobacterial virulence factors. One of them is encoded by the RD1 locus, which was first discovered by investigating the genome deletions in the attenuated Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine strain. Studies performed also with M. marinum found it to be the main virulence determinant [18], [19]. The locus encodes a type 7 secretion system, called ESX-1 system [18]. It was shown that RD1 mutants are less effective in arresting phagosome maturation and are attenuated in infection dissemination [18], [20]–[23].

TB Treatment, Search for New Drugs

The standard treatment for tuberculosis uses a combination of antitubercular compounds for six months or longer. The necessity of extensive treatment was elaborated after a long period of trial and error. It is now clear that noncompliance with the treatment, short-term and relaxed therapy regimens result in the emergence of drug resistant strains. The situation has escalated even further due to emergence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains and, finally, extensively drug resistant (XDR) strains, and more recently some totally drug resistant strains have been described [24]. As a consequence, the WHO reviewed the strategy to fight TB infections, leading to the establishment of “directly observed treatment short course” (DOTS) (WHO report 2011).

The newest drug for TB treatment is 30 years old, and the previously very effective streptomycin lost its efficiency against M. tuberculosis and is no longer used for therapy. Therefore, the need for new drugs has become obvious. Several reasons underlie the lack of new drugs, such as the difficulty to identify compounds that penetrate mycobacteria, because of the low permeability of the mycolate-rich cell wall or because of the low metabolic and growth rates reflected by their 24–36 hours doubling time. In addition, conventional screening approaches usually favour the search for bactericidal compounds while at the same time neglecting host-pathogen interactions.

Despite the challenges mentioned above, several drug candidates are currently under development and have a good chance to enter the market. Promising approaches for drug development include targeting synthesis of lipids as nutrients [25], [26] and synthesis of mycolic acids as major components of the cell wall [27]. In the last decade, researchers have identified compounds that kill dormant bacteria by intracellular NO release, such as the bicyclic nitroimidazoles, PA-824 [28], and OPC-67683, as well as compounds that affect ATP-synthesis such as TMC207 [29] and nitrofuranylamide compounds with so far unknown mode of action [30]. Some screens revealed prodrugs that are activated by the metabolism of the host cell, such as nitroimidazopyran [31]. Potentially interesting compounds also include heterocyclic aldehydes [32], oxazole- and oxazoline-containing compounds that target iron uptake [33], and rhodanine derivatives that target the dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase [34].

Whole-cell Based Screening, a Promising Alternative to Target-based Approaches

Standard target-based approaches identified compounds that showed very high attrition rates and low numbers of validated hits against the intact live bacterium and in infection systems [35], [36]. Meanwhile, a broad spectrum of new tools has become available [37]. A new trend has emerged: phenotypic screens in a whole-cell infection system [38], [39]. Whole-cell screens are a promising method to provide lead-structures and identify new targets. Unlike target-based approaches they fulfill in vivo criteria such as membrane permeability and a higher activity against mycobacteria than host cells. However, whole-cell based assays typically do not easily reveal the mechanism of action. Additional mechanistic studies and rounds of structure-activity relationship investigations are required.

Establishing alternative methods to target-based screening may improve the chances to discover new sets of drugs that could be competitive with current drugs, shorten the duration of treatment, avoid significant drug-drug interactions, and successfully deal with MDR and XDR Mtb strains. The ability of whole-cell screens to detect host response in situ makes it possible to reveal not only antibiotic activities, but also anti-infective drugs. Such compounds target infection-specific biological processes, and therefore, significantly reduce the risk of acquiring resistance. A proof of feasibility for the identification of such active compounds was established in a few recent studies (reviewed in [40]). For M. tuberculosis, the list contains inhibitors of iron metabolism [41] and compounds targeting resistance to oxidative stress [34]. Moreover, whole cell-based approaches allow detection of compounds that increase the activity of natural, host-specific innate immune defense mechanisms. This opens the possibility of discovering compounds capable of helping the host cell deal with a broad range of pathogens. For example, the cellular pool of kinases and phosphatases was shown to be the targets of defense-boosting compounds [39], [42]–[44].

Mycobacterium marinum as a Pathogen Model for Drug Screening Purposes

As mentioned above, despite the fact that many screens resulted in the discovery of promising antimycobacterial compounds, overall screening for anti-Mtb drugs remains ineffective [29], [30], raising the demand for new strategies, including the use of new and more cost-efficient host-pathogen models.

M. marinum, the closest relative of Mtb in the tuberculosis complex, is an attractive alternative model. M. marinum is a fish and frog pathogen which establishes an infection similar to human tuberculosis [34]. Bacterial growth temperature is optimal at 30°C, rendering it less dangerous for humans, as it is only capable to establish superficial skin lesions [45]. Moreover its doubling time of eight hours is much shorter than that of Mtb and M. bovis BCG, which in turn improves the speed of detection of antimycobacterial effects. For M. marinum the mechanisms of phagosome maturation arrest, as well as the activity of many virulence genes are very similar to M. tuberculosis [20], [46]. M. marinum readily escapes its vacuole [47], but the efficiency and relevance of this process for Mtb is still debated [48]. The high degree of functional conservation in virulence genes supports the theory that ancient mycobacterial precursors developed the mechanisms of pathogenesis against phagocytic protozoa and that mycobacteria are now using them to hijack animal immune phagocytes [49]. Indeed it has been shown that free-living amoebae can be an environmental reservoir for pathogenic bacteria such as M. avium, M. marinum and even Mtb [50].

For M. marinum, well-developed genetic and cellular biology tools are available. These features render M. marinum extremely useful for the investigation of the mode of action of antitubercular compounds and for the validation with the M. tuberculosis model [51].

Amoebae Host Systems for Drug Screening

Among whole-cell based assays the usage of unicellular hosts is advantageous because of the ease of cultivation and manipulation important in high-throughput screening. Although protozoa do not engage in complex multicellular interactions, the high degree of conservation of innate immune defense mechanisms renders them attractive alternative systems for experimental infection studies. Within the host one can target multiple pathways involved at different stages of the infection, including endosomal trafficking during phagocytosis of the bacteria, the autophagy pathway in the form of xenophagy, ion-pumps recruitment involved in bacteria degradation during phagosome maturation, kinases and phosphatases signaling that affect the course of infection (reviewed in [49], [52], [53]).

Since the primary target of Mtb is macrophages, amoebae that are also professional phagocytes, are a rational choice to study host-pathogen interactions. Amoebae offer a well-balanced compromise between the natural complexity of the system on one side and ease of manipulation and cultivation on the other. Amoebae and macrophages possess a high degree of functional conservation in defense mechanisms against infection [54]. Many species of amoebae serve as a natural reservoir and a training field for pathogens.

Acanthamoeba are a particularly promising genus of amoebae for screening purposes. Its environmental niches include soil, air and fresh water. Unlike Dictyostelium discoideum, a soil-inhabiting social amoeba that is another popular protozoan model, Acanthamoeba does not undergo a multicellular developmental phase, which probably renders them less sensitive to the stress factors inevitable in screening processes. Acanthamoeba is considered to be a natural carrier for many mycobacteria species [55], for example it was shown that 25 mycobacteria species, including non-tuberculous mycobacteria, can infect both trophozoites and cysts of Acanthamoeba polyphaga [56]–[58]. Moreover, intracellular M. avium within Acanthamoeba castellanii showed increased resistance to bactericidal compounds such as rifabutin, compared to growth within macrophages [56], [59]. The ability to protect from antitubercular drugs may serve as an additional in vivo filter to subtract false-positive hits of drug screening. On the other hand, the D. discoideum model system has its own unique advantages, particularly a complete set of genetic tools that are extremely useful for the determination of mechanisms of action. Together with a fully sequenced and annotated haploid genome, D. discoideum is amenable to forward and reverse genetics. Its simplicity of cultivation makes it easily biochemically tractable. D. discoideum also allows excellent real-time live imaging. Taken together, both amoeba genera are useful models, each having its advantages depending on the purpose of the experiments.

In the present study we have established the A. castellanii – M. marinum host-pathogen system as a robust compound screening and validation system. Together with secondary assays using D. discoideum and M. marinum, it shows excellent promise to identify novel antitubercular hits.

Results

A Fluorescence- and Cell-based Assay to Measure Intracellular Mycobacterial Growth in A. castellanii

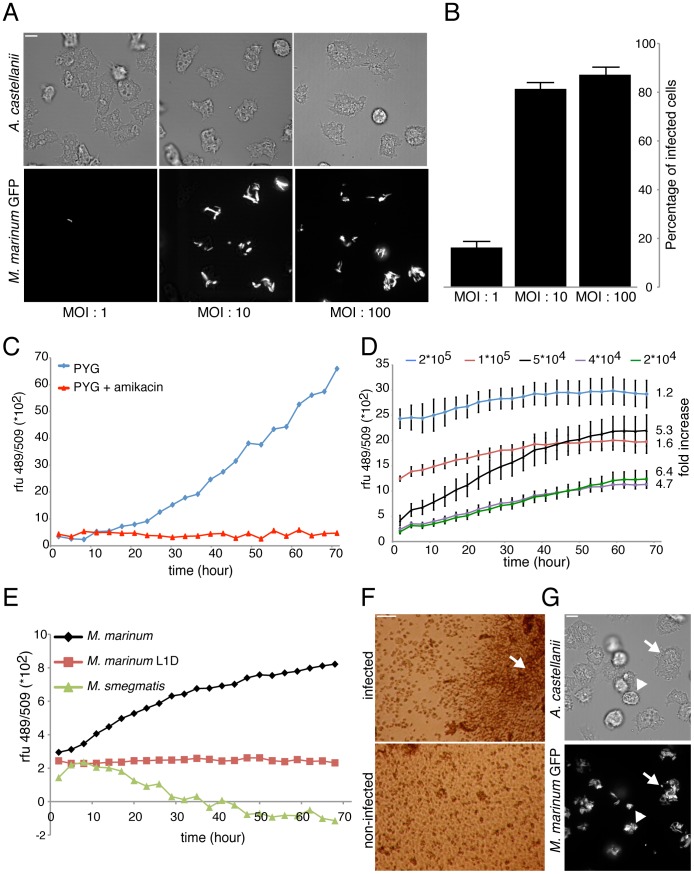

In this study, we present a fast and easy approach to identify compounds with anti-infective properties in a cellular host context. M. marinum is able to replicate efficiently in the free-living fresh water amoeba A. castellanii [60]. We therefore used A. castellanii to monitor intracellular growth of M. marinum using a fluorescence-based assay. A. castellanii was chosen instead of our D. discoideum model due to its ‘macrophage-like’ size that allows a higher level of bacteria uptake, easily detectable with our fluorescence plate reader. The protocol established uses an optimized multiplicity of infection (MOI) and is based on synchronous and homogeneous bacterial phagocytosis. Spinoculation of mycobacteria on top of a cell monolayer close to confluency maximizes host-bacteria contact and subsequent uptake and thus guarantees high reproducibility of the infection course. The percentage of infected cells at time zero and the average number of bacteria per cell is a function of the MOI (Figure 1A). Using an MOI of 10∶1 ensures that a majority of cells (≈ 80%) are infected (Figure 1B) with approximately 1 to 5 bacteria per cell, and thus, this condition became our infection standard. Then, excess extracellular bacteria were carefully removed by washing with PYG medium, prior to testing compounds of interest on infected cells. [61]–[63]Finally, infected cells were resuspended in PYG medium containing amikacin to prevent extracellular growth of bacteria [64]. Using 10 µM amikacin prevented bacteria proliferation in PYG medium for at least three days (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Mycobacteria infection of A. castellanii.

A. Confocal (top) and brightfield (bottom) pictures of A. castellanii infected with GFP-expressing M. marinum at different MOI. Scale bar, 10 µm. B. Corresponding percentage of infected cells under the three MOI conditions, error bars represent the standard deviation from technical replicates (three microscopy fields and at least forty counted cells) of one representative experiment. C. Growth kinetics of M. marinum msp12::GFP in PYG medium supplemented with 10 µM amikacin, representative experiment from a series with similar outcome. D. Growth kinetics of GFP-expressing M. marinum within A. castellanii plated at different densities, measured by total fluorescence intensity. The standard deviation derives from the technical mean of eight microwells. The values on the right represent the fold fluorescence increase between 2 and 68 hours post infection. E. Representative experiment of growth kinetics of GFP-expressing M. smegmatis, M. marinum WT and L1D mutant strains within A. castellanii, measured by fluorescence intensity. F. Brightfield microscopy of the cells at the bottom of a microwell. Infected cells at 3 DPI under control conditions and non-infected cells. Scale bar is 100 µm. G. Phase contrast (top) and confocal (bottom) pictures of A. castellanii infected cells with GFP-expressing M. marinum at three days post-infection. Infected giants cells (arrow), and some dead cells (arrowhead) are observed. Scale bar, 10 µm.

In order to adapt the monitoring of infection to a larger scale, a fluorescence plate reader assay was optimized for the 96-well plate format. Use of mycobacteria strains expressing fluorescent reporters has recently been validated for the quantitative measurement of bacterial mass, as an alternative to c.f.u. counting, both for microscopy on live and fixed cells and organisms, as well as higher throughput methods such as microwell-plate readers [61]–[63]. The fluorescent M. marinum msp12::GFP strain [65] gave us the most robust readout to quantitate the increase in bacterial numbers, but other fluorescent and bioluminescent reporters can also be used [66]. As shown in figure 1D, the plating density of initially infected cells (obtained with an MOI 10∶1) was a parameter that greatly impacted intracellular bacterial growth. As indicated at the right of the graph, the fluorescence fold increase at 3 days post infection (DPI) was low at high cell density (1.2 and 1.6 for 2*105 and 1*105 cells/well, respectively) and bacterial growth kinetics reached a plateau after 30–40 hours post infection (HPI). In contrast, lower densities that allowed host cells to grow for at least two days before reaching confluency, resulted in a higher bacterial expansion (4–6 fold increase with 2 to 5*104 cells/well). Therefore, we decided to plate between 1 and 5*104 infected cells in each well of the 96-well plate.

We validated our assay by monitoring A. castellanii infection with the non-pathogenic mycobacterium, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and an avirulent mutant, M. marinum-L1D [65]. As presented in figure 1E, the total fluorescence of GFP-M. smegmatis decreased over time, indicating that the bacteria are killed and digested by the amoebae. In addition, similarly to its fate in zebrafish and macrophages, the M. marinum-L1D mutant was not able to replicate in A. castellanii. Similar results have been reported using the D. discoideum host [47]. However, M. marinum-L1D’s fluorescence remained stable, indicating that A. castellanii appears unable to fully digest this strongly attenuated M. marinum strain.

Under our conditions, A. castellanii infection with M. marinum appeared to severely decrease the growth and/or survival of the amoebae. Inspection of the wells by phase contrast microscopy showed that infected A. castellanii cells did not reach maximal confluency at 3 DPI, concomitantly with a notable accumulation of extracellular bacteria at the well centre (Figure 1F, arrow). Further inspections showed that heavily infected and dead amoebae, as well as abnormal giant cells are often observed during the late phase of infection (Figure 1G, arrowhead and arrow, respectively). Lethality induced by M. marinum infection has been reported in many animal systems such as the Drosophila larvae [67], leopard frog [68], and in macrophages [69]. Amoeba lysis has also been mentioned as a result of infection with other intracellular pathogens, such as Legionella pneumophila [70].

Drug Validation

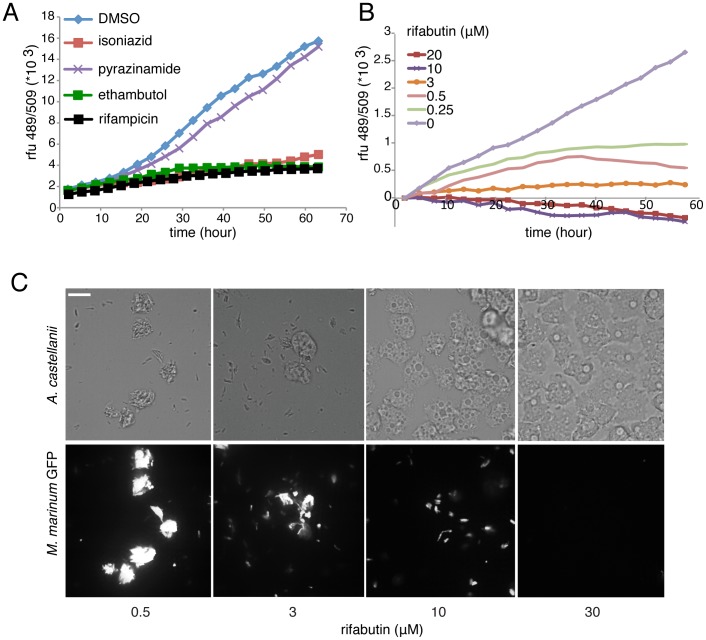

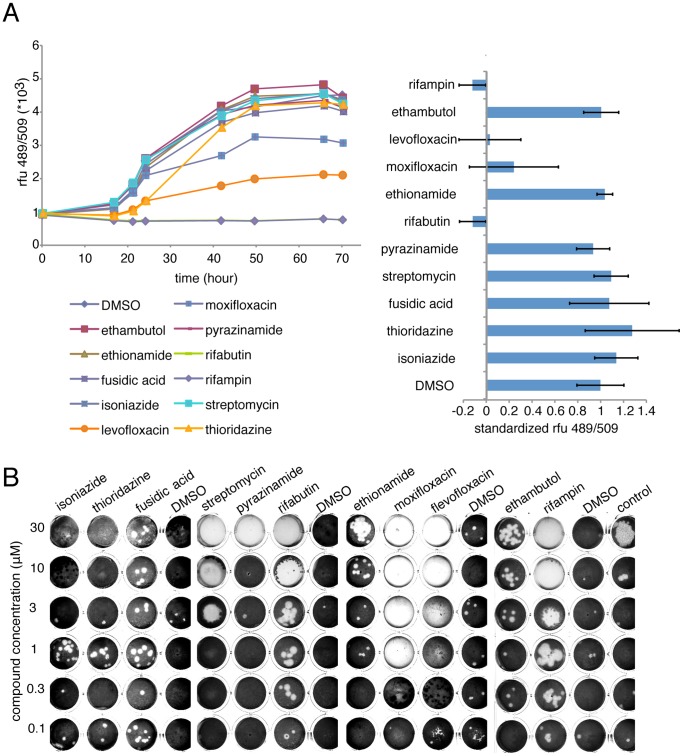

As a close cousin of M. tuberculosis, M. marinum is sensitive to most standard antibiotics used to treat tuberculosis, and also used to validate various screenings protocols [62], [71]. In our host-pathogen infection model, most first line anti-tubercular drugs are efficient. Isoniazid (INH), ethionamide and ethambutol were active at 30 µM and efficiently blocked intracellular mycobacterial growth, only pyrazinamide was not active (Figure 2A). A rifamycin family derivate, rifabutin, was the most potent antibiotic in our infection assay with an MIC around 0.25 µM (Figure 2B). We also confirmed that rifabutin curing of an M. marinum infection occurred in a dose-dependent manner, and was consistent with confocal microscopy observations of infected cells (Figure 2B and C). At three days post infection, the intracellular bacteria load drastically diminished in presence of rifabutin, as reported by the total fluorescence intensity of bacteria inside infected cells (Figure 1). It is notable that rifabutin action on infection also restored host cell growth in a dose-dependent manner, as judged by the host cell density in Figure 2C. Finally, we assayed a panel of known specific anti-tubercular compounds and broad-spectrum antiobics to treat another intracellular pathogen infection, L. pneumophila, in the A. castellanii host (Figure 3A). Despite the common ability of these pathogens to avoid phago-lysosomal fusion, the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) differs from the M. marinum phagosome-derived compartment, and therefore, as expected, most of the anti-tubercular antibiotics have no effect on L. pneumophila replication. Only drugs such as floxacins [72] and rifampin [73], already reported to be active against L. pneumophila, cure A.castellanii infected cells.

Figure 2. Effect of antibiotics on intracellular growth of M. marinum during an infection.

A. Intracellular growth kinetic of GFP-expressing M. marinum measured by fluorescence intensity in the presence of 30 µM of first-line antibiotics. B. Intracellular growth kinetics of GFP-expressing M. marinum measured by fluorescence intensity, in the presence of different concentrations of rifabutin. A and B are representative experiments from a series with similar outcome. C. Effect of rifabutin on M. marinum growth during an infection. Brightfield (top) and spinning disc confocal (bottom) imaging of A. castellanii infected with GFP-expressing M. marinum in the presence of the indicated concentrations of rifabutin, 72 hours post infection.

Figure 3. Effect of antibiotics on intracellular growth of L. pneumophila during an infection and in a ‘phagocytic plaque assay’.

A. Left, representative experiment from a series with similar outcome of intracellular growth kinetic of GFP-expressing L. pneumophila measured by fluorescence intensity in the presence of 30 µM of antibiotics. Right, normalized intracellular bacterial growth (DMSO = 1) in A. castellanii, error bars represent the standard deviation from biological triplicates. B. Ability of D. discoideum DH1 strain (1000 cells/well) to grow on a bacterial lawn composed of M. marinum and Klebsiella pneumoniae (2::1 ration) after seven days and in presence of antibiotic compounds.

Because amoebae naturally graze on most innoccuous bacteria but fail to grow on pathogenic bacteria [74], this discriminating ability can be used in an alternative screening assay to test compounds’ ability to restore amoeba growth on a mixture of pathogenic mycobacteria with non-pathogenic Klebsiella pneumoniae [75]. As shown in figure 3B, even though this assay is conceptually different from the GFP-based detection assay, it also detects specific anti-mycobacterial antibiotics. However, broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as streptomycin or high concentrations of an anti-tubercular such as isoniazid, eradicate all bacteria and therefore, do not allow D. discoideum to generate phagocytic plaques.

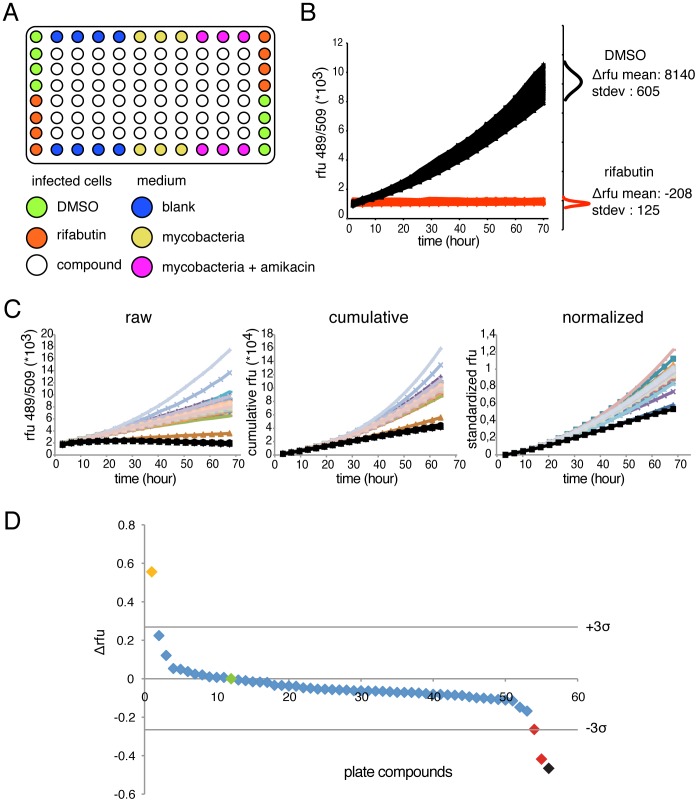

Assay Suitability for Drug Screening and Data Analysis

Next, we sought to adapt the GFP-based intracellular growth assay for medium-throughput analysis using 96-well plates. Border wells are dedicated to controls needed to test bacteria fitness and amikacin efficiency (Figure 4A). As rifabutin efficiently cures the infection, we decided to include it in the experimental plate design as positive control. Wells containing DMSO (at 1‰, as compound carrier) and rifabutin (10 µM) are used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Therefore, 64 compounds can be tested per 96-well plate. We next measured the quality of our screening protocol to detect potential hits by calculating a Z factor that is a usual parameter to assess screen robustness [76]. From a single standard infection, cells were dispensed in 96-wells, half containing DMSO and half containing 10 µM rifabutin, as shown in figure 4B. The assay sensitivity is high as both controls are clearly separated and, as attested by the standard deviation of the mean, variability between identical wells is low. In both cases, the end-point fluorescence values at 3 days post infection (DPI) were normally distributed. Overall assay robustness is attested by a Z factor score of 0.74 that is excellent for an ‘in vivo’ biological assay, and allows to initiate compounds screening with reasonable confidence.

Figure 4. Screening protocol for anti-tubercular compounds.

A. Scheme of the plate design in 96-well format for compounds screening. B. Left, representative experiment of intracellular growth kinetic of GFP-expressing M. marinum measured by fluorescence intensity obtained from one control 96-well plates in presence of DMSO (N = 48) or 10 µM of rifabutin (N = 48). The small graphs on the right represent the normal distribution of the fluorescence difference between 2 and 72 hours of infection for DMSO and rifabutin. Consequently, the Z factor of this experiment was 0.74. C. For the statistical analysis, the data are treated in three steps. First, from the raw data, the value at 68 hours is subtracted from all others and a cumulative fluorescence curve is drawn. Then, the curves are normalized to the DMSO standard control. Graphs are representative of one experimental screening plate. D. Differential fluorescence values obtained from one experimental plate with diverse compounds are plotted. Horizontal bars represent 3-fold standard deviation from the DMSO mean. The green dot corresponds to the normalized DMSO controls; the orange dot to a putative pro-infectious compound; the black dot to the average of the rifabutin controls; the two red dots to two putative anti-infective compounds. The graph is representative of one experimental screening plate.

To allow direct comparison from several plates and multiple infection rounds, raw fluorescence kinetic data (figure 4C, left curve) were transformed. First, to integrate the entire history of the growth kinetics, cumulative curves were built rather than simply using the endpoint measurements were built, and the first point was standardized to 0 by subtracting the value at time zero from each data point (Figure 4C, middle) were transformed as follows. Second, the last value point was standardized to 1 for the mean value of the DMSO controls (Figure 4C, right). Next, normalized cumulative values were ranked relative to the increase or decrease of bacterial growth compared to the DMSO. Representative results from a single experimental plate are presented in figure 4D. The plot represents the difference between the DMSO mean value and each compound of interest. The significance of a compound’s effect was first statistically assessed by its difference from the DMSO control, a difference of more than two or three standard deviations of the DMSO mean being considered significant. Moreover, the strength of inhibition or promotion of bacterial growth was measured by its relative normalized score compared to 1 (DMSO).

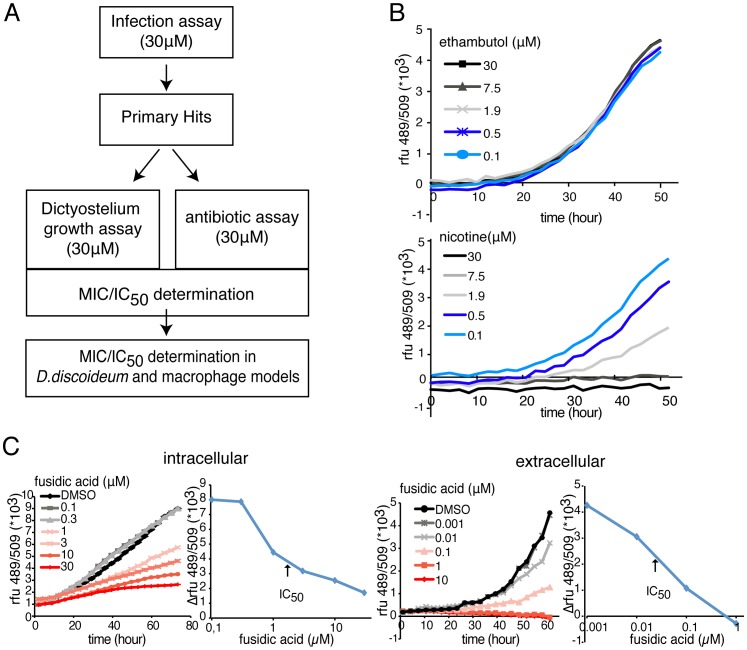

Workflow and Secondary Assays

In order to successfully conduct a screen to identify potential compounds of interest in a complex biological assay, secondary assays are often established and implemented prior to further structure activity relationship studies. In our specific assay setting, two further and major pieces of information can be easily extracted: compound toxicity to the host alone, and antibiotic effect on the bacterium in vitro. A basic representation of the screen workflow is presented in figure 5A. The effect of the hit compounds on the host growth and health was tested in the plate reader format with a D. discoideum strain expressing a fluorescent reporter, GFP-ABD [77]. For example, we monitored the growth kinetic of this strain in the presence of a classical anti-tubercular antibiotic, ethambutol, and a toxic compound, nicotin (Figure 5B). Ethambutol produced no detectable effect on D. discoideum growth, as also observed with most classical antibiotics tested so far, whereas nicotin affects cell growth in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Secondary assays for identifying compounds properties.

A. Basic scheme of screen workflow including the growth inhibition/cytotoxicity assay and the antibiotic assay before hit validation in other host models system. B. Growth inhibition/cytotoxicity assay. Growth kinetics of GFP-expressing D. discoideum AX2 cells measured by fluorescence intensity, in the presence of various concentrations of ethambutol (top) or nicotin (bottom). C. antibiotic assay. Left, intracellular and Right, intracellular growth kinetic of GFP-expressing M. marinum measured by fluorescence intensity in the presence of various concentrations of fusidic acid, accompanied by the corresponding graphs for IC50 determination. B and C are representative experiments from a series with similar outcome.

A similar assay was used to test the antibiotic activity of the hit compounds directly on M. marinum in its standard culture broth (7H9). For example, fusidic acid, a second line antibiotic used for tuberculosis treatment was tested at various concentrations on extracellular and intracellular M. marinum, (Figure 5C). In both cases a half inhibitory concentration (IC50) can be calculated. IC50 values obtained with a small collection of classical anti-tubercular antibiotics are presented in Table 1. Overall, the data highlight a shielding effect of the amoeba host, protecting the mycobacteria from the antibiotics, as previously demonstrated using M. avium [59]. In our assay, only rifabutin showed a better effect when tested as anti-infective in vivo rather than as antibiotic in vitro. This phenomenon is probably explained by its higher liposolubility, which likely enhanced membrane permeability and consequently increased its concentration inside the host cell [78].

Table 1. Inhibitory concentrations 50% (IC50) values for M. marinum growth in extracellular and intracellular conditions.

| antibiotic | extracellular IC50 (µM) | intracellular IC50 (µM) |

| streptomycin | 0.1–1 | 3–7 |

| fusidic acid | 0.01–0.1 | 3–5 |

| ethionamide | 0.1–1 | 3–10 |

| isoniazid | 5–10 | 20–30 |

| rifampin | 0.1–0.5 | 3–10 |

| rifabutin | 2–3 | 1–3 |

| ethambutol | 5–10 | 5–10 |

| levofloxacin | 10–30 | >30 |

| moxifloxacin | 5–10 | >30 |

| thioridazine | 1–5 | 5–10 |

| PA-824 | 3–5 | 5–10 |

As presented in Figure 5C, GFP-expressing M. marinum growth kinetics were measured in broth culture and during cellular infection in presence of antibiotics in a concentration range, and IC50 values were graphically determined from a series of experiments with similar outcome.

Discussion

In the present study, we detail a screening method to detect anti-tubercular compounds acting in the context of infected amoeba host cells. We first developed and validated suitable conditions for medium throughput screening (MTS). We used fluorescent mycobacteria to monitor intracellular growth in real time by recording fluorescence increase in a 96-well microplate reader. So far, the use of fluorescent mycobacteria is a consensus to avoid the counting of colony forming units, which is hardly compatible with MTS procedures, and allow a fast and reliable way to measure bacterial growth. However, some obvious limitations are due to this detection method. There is no direct way to known how healthy the remaining bacteria are, whose fluorescence remains stable over time. Presently, only a clear decrease in fluorescence intensity, as observed with rifabutin, reflects of a probable bactericidal effect. The long half-life of GFP and the resistance of mycobacteria to cell lysis conferred by their particularly thick cell wall partly explain this phenomenon. Moreover, with this readout, compounds that interfere with cell metabolism, expression of the reporter, or quench its fluorescence can be identified as false positives.

Additionally, introducing host cell-specific fluorescent markers allows the dissection of compound effects on various cell processes like phago-lysosomal trafficking, autophagy induction or lipid storage. Altogether, these fluorescent cell-based approaches can easily be adapted to monitor multiples parameters in a high-content microscopy approach [38]. Therefore, integration of these secondary readouts can provide preliminary knowledge about the mode of action of a compound [39].

As expected, the initial conditions of the infection largely influence the kinetics of bacterial growth. Multiple parameters (percentage of infected cells, cell density, host and bacteria physiological state) modulate the final apparent increase over almost a log range (data not shown). We clearly observe that exponentially growing host cells facilitate bacterial expansion, whereas high confluence partially suppresses it. These findings suggest that cell-to-cell transmission, as observed in D. discoideum, is also a significant parameter in A. castellanii infections [47].

Surprisingly, depending on the initial bacterial load, the mycobacteria infection leads to host cell death between two to five DPI. Significant cytotoxicity towards the host cell has not been reported during D. discoideum infection [79], but was previously noted in macrophages infected by M. tuberculosis and M. marinum at high MOI and under conditions where phagosomal rupture occurred [69], [80]. Modulation of apoptotic and necrotic cell death has been reported in macrophages infected with virulent and avirulent strains of M. tuberculosis [81]. However, in the absence of caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways in amoebae, infection by M. marinum likely leads to the necrotic and/or autophagic cell death, mechanistically perhaps similar to the pathways documented in the model amoeba D. discoideum [82].

IC50 determination of antibiotics in extracellular conditions and within the amoeba host emphasizes the shielding role of A. castellanii, as previously shown for M. avium [59]. This capacity of A. castellanii to protect against antibiotics may be due to a lower membrane permeability and/or enhanced host efflux pump mechanisms that purge intracellular drugs. This observation implies that our assay operates at high stringency to select hit compounds with low IC50. Even if direct comparison of anti-tubercular intracellular IC50 obtained in various studies is difficult, because of the differences in conditions used (MOI, time resolution), bacterial strains (M. tuberculosis, BCG, M. marinum) and host (macrophages, amoeba, zebrafish, D. melanogaster), the IC50 we calculate for our assay reveal a similar shielding effect as seen for other mycobacteria such as M. avium during infection in A. castellanii [59].

In this study, we reported successful activity of most known anti-tubercular antibiotics to eradicate or attenuate intracellular M. marinum growth, with the exception of pyrazinamide. It is known that a low acidic pH is needed to convert pyrazinamide into an active drug, pyrazinoic acid [83], and so far, no data has been published about the pH inside the mycobacteria-containing compartment in amoebae. As discussed in a study reporting about the D. melanogaster/M. marinum infection model [84], a lack of vacuole acidification could lead to a poor conversion of the pro-drug into its active form, and thus might explain the inefficiency of pyrazinamide in our system. In addition, a recent paper Ahmad et al [85] showed that the minimum inhibitory concentration of pyrazinamide against M tuberculosis and M. bovis is high. Finally, several Mycobacteria strains such as M. canettii are naturally resistant to pyrazinamide [86], as well as clinical isolates of M. kansasii and M. marinum [87]. Therefore, a higher concentration of pyrazinamide could be needed to impact on M. marinum replication in our system.

From our standard experimental data, we calculated a Z factor that lies between 0.6 and 0.8, values that are commonly accepted as highlighting the robustness of an assay [76]. Moreover, we also present here the flow of statistical data analysis that guides us to identify primary hits. Transformations of the raw kinetic data are made to take into account the global history of the growth curve and not only the difference between the values at the first and last time points. This method allows for the robust detection of both anti-infective and pro-infective molecules. Finally, our workflow comprises two secondary assays. A growth inhibition assay using fluorescent D. discoideum is used to determine an IC50 for negative effects on the host. This allows then to estimate a therapeutic window between effects on the intracellular bacteria and on its host. Yet, the data obtained for amoebae have to be validated for mammalian host cells, e.g. macrophages. The antibiotic assay performed on extracellular bacteria is used to quantitate the difference in efficacy between the effect of the compound on extracellular versus intracellular bacteria, which will permit to identify compounds with most relevant anti-infective activities, being anti-virulence or host defence-boosting mode of action.

Overall, we detailed the establishment of an MTS pipeline for an ‘in vivo’ anti-tubercular screen allowing to test in moderate turnover time, 64 molecules per 96-well plates, with excellent sensitivity and good anti-mycobacterial specificity. Finally, we speculate that the use of amoebae hosts, which are natural vectors for many bacteria and have already proven powerful in the elucidation of mechanisms underlying host-pathogen relationships [47], [79], also represent a worthy alternative model to contribute to hit and lead identification and drug development to fight tuberculosis.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria and Cell Cultures

Acanthamoeba castellanii (ATCC 30234) was grown in PYG medium at 25°C as described (Moffat and Tompkins, 1992; Segal and Shuman, 1999) using proteose peptone (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) and yeast extract (Difco). The D. discoideum strain expressing GFP-ABD [71] was grown in HL5c medium at 22°C. Mycobacteria, the M. marinum M-strain (wild-type), the L1D mutant [65] and M. smegmatis (generous gift from Gareth Griffiths) were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) supplemented with 10% OADC (Becton Dickinson), 5% glycerol and 0.2% Tween80 (Sigma Aldrich) at 32°C in shaking culture. M. marinum and the msp12::GFP plasmid were gifts from Dr. L. Ramakrishnan (Washington University, Seattle, USA). The M. marinum strain expressing GFP in a constitutive manner was obtained by transformation with msp12::GFP, and cultivated in the presence of 20 µg/ml kanamycin.

Acanthamoeba Infection Assay

A. castellanii were cultured in PYG medium in 10 cm Petri dishes at 25°C, and passaged the day prior to infection to reach 90% confluency. M. marinum were cultivated in a shaking culture at 32°C to an OD600 of 0.8–1 in 7H9 medium. Mycobacteria were centrifuged onto a monolayer of Acanthamoeba cells at an MOI of 10 to promote efficient and synchronous uptake. Centrifugation was performed at RT at 500 g for two periods of 10 min. After an additional 20–30 min incubation, extracellular bacteria were washed off with PYG and infected cells were resuspended in PYG containing 10 µM amikacin. 5×104 infected cells were transferred to each well of a 96-well plate (Cell Carrier, black, transparent bottom from Perkin-Elmer) with preplated compounds and controls. The course of infection at 25°C was monitored by measuring fluorescence in a plate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek) for 72 hours with time points taken every 3 hours. Time courses were plotted and data from all time points were used to determine the effect of compounds versus vehicle controls. To take into account possible autofluorescence of the compounds, RFU data of the first time point were subtracted from all time points. Cumulative curves were calculated. The activities of the compounds were determined by analysing maximum difference of compound cumulative curve to the 12–16 vehicle controls.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Acanthamoeba cells were infected with GFP-expressing M. marinum as described above. Infected cells were monitored in 96-well plates (Cell Carrier, black, transparent bottom from Perkin-Elmer). Recordings were performed using a Leica LF6000LX microscope (100x 1.4 NA oil immersion objective).

Phase Contrast Microscopy

Acanthamoeba cells were infected with GFP-expressing M. marinum as described above. Infected cells were monitored in 96-well plates (Cell Carrier, black, transparent bottom from Perkin-Elmer). Recordings were performed using a CKX41 inverted microscope.

Antibiotic Activity Assay

104 GFP-ABD-expressing D. discoideum cells were transferred to each well of 96-well plates allowed to attach for 20–30 min. Cell growth at 25°C was monitored by measuring the GFP fluorescence in a fluorescent plate reader (Synergy H1, company) for 72 hours with a time point taken every 3 hours.

Growth Inhibition Assay

105 GFP-expressing M. marinum were transferred to each well of 96-well plates. Bacterial growth at 25°C was monitored by measuring the GFP fluorescence in a fluorescent platereader (Synergy H1) for 72 hours with a time point taken every 3 hours.

Statistical Analysis

The Z factor was calculated using the means and standard deviations of both positive and negative controls (µp, σp and µn, σn). The following formula was applied: Z-factor = 1–3(σp+ σn)/|µp-µn|.

Intracellular Replication of L. pneumophila

A. castellanii amoebae were cultured in PYG medium and passaged the day prior to infection such that 2×104 cells were present in each well of a 96-well plate (Cell Carrier, black, transparent bottom from Perkin-Elmer). Cultures of L. pneumophila harbouring the GFP-producing plasmid pNT-28 were resuspended from plates to a starting OD600 of 0.1 in AYE medium, and grown overnight on a rotating wheel at 37°C to an OD600 of 3. Bacteria were diluted in LoFlo medium (ForMedium) such that each well contained 8×105 bacteria, an MOI of 20. Infections were synchronised by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes. Infected cultures were incubated in a 30°C incubator and the GFP fluorescence was measured by a plate spectrophotometer at appropriate intervals (Optima FluoStar, BMG Labtech) [88]. Time courses were constructed and data from the point directly after entry up to stationary phase were used to determine the effect of compounds versus vehicle control.

Dictyostelium Growth on a Bacteria Lawn

Because D. discoideum cannot grow on lawns of virulent M. marinum, a specific growth assay was developed [89]. It consists in resuspending a pellet from one volume of centrifuged mid-log phase mycobacterial cultures in an equal volume of an overnight culture of K. pneumoniae diluted 105 fold. Then, 50 µl aliquots of the bacterial suspension were plated on 2 mL plugs of solid SM+Glucose agar medium in a 24-well plate format and left to dry for 2–3 hours. Finally, 1,000 D. discoideum cells were added on top of the bacterial lawn. Plates were incubated for 5–9 days at 25°C and the formation of phagocytic plaques was monitored and quantified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ophelie Patthey for her technical help, and Dr Lalita Ramakrishnan for the msp12::GFP construct and the M. marinum M strain.

Funding Statement

The work was supported by a Sinergia grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO_report (2011) http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/en/index.html (accessed November 23, 2012).Global tuberculosis control.

- 2.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell R, Robbins N (2007) Basic pathology (8th edition): 516–522.

- 3. Armstrong JA, Hart PD (1971) Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J Exp Med 134: 713–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bermudez LE, Goodman J (1996) Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades and replicates within type II alveolar cells. Infect Immun 64: 1400–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warner DF, Mizrahi V (2007) The survival kit of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med 13: 282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tailleux L, Neyrolles O, Honore-Bouakline S, Perret E, Sanchez F, et al. (2003) Constrained intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human dendritic cells. J Immunol 170: 1939–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russell DG (2001) Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today, and here tomorrow. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, et al. (2004) Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119: 753–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar D, Nath L, Kamal MA, Varshney A, Jain A, et al. (2010) Genome-wide analysis of the host intracellular network that regulates survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 140: 731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koul A, Herget T, Klebl B, Ullrich A (2004) Interplay between mycobacteria and host signalling pathways. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keane J, Remold HG, Kornfeld H (2000) Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains evade apoptosis of infected alveolar macrophages. J Immunol 164: 2016–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Behar SM, Divangahi M, Remold HG (2010) Evasion of innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: is death an exit strategy? Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 668–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger PH, Chakraborty P, Haddix PL, Collins HL, et al. (1994) Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science 263: 678–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fratti RA, Chua J, Vergne I, Deretic V (2003) Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycosylated phosphatidylinositol causes phagosome maturation arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 5437–5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vergne I, Chua J, Lee HH, Lucas M, Belisle J, et al. (2005) Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 4033–4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neufert C, Pai RK, Noss EH, Berger M, Boom WH, et al. (2001) Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein promotes neutrophil activation. J Immunol 167: 1542–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walburger A, Koul A, Ferrari G, Nguyen L, Prescianotto-Baschong C, et al. (2004) Protein kinase G from pathogenic mycobacteria promotes survival within macrophages. Science 304: 1800–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abdallah AM, Gey van Pittius NC, Champion PA, Cox J, Luirink J, et al. (2007) Type VII secretion–mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gao LY, Guo S, McLaughlin B, Morisaki H, Engel JN, et al. (2004) A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol Microbiol 53: 1677–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cosma CL, Klein K, Kim R, Beery D, Ramakrishnan L (2006) Mycobacterium marinum Erp is a virulence determinant required for cell wall integrity and intracellular survival. Infect Immun 74: 3125–3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, et al. (2002) Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity 17: 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis JM, Ramakrishnan L (2009) The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell 136: 37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith NH, Clifton-Hadley R (2008) Bovine TB: don’t get rid of the cat because the mice have gone. Nature 456: 700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muller B, Borrell S, Rose G, Gagneux S (2013) The heterogeneous evolution of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Genet 29: 160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arora P, Goyal A, Natarajan VT, Rajakumara E, Verma P, et al. (2009) Mechanistic and functional insights into fatty acid activation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Chem Biol 5: 166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Munoz-Elias EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J, McKinney JD (2006) Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Mol Microbiol 60: 1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsumoto M, Hashizume H, Tomishige T, Kawasaki M, Tsubouchi H, et al. (2006) OPC-67683, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole derivative with promising action against tuberculosis in vitro and in mice. PLoS Med 3: e466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh R, Manjunatha U, Boshoff HI, Ha YH, Niyomrattanakit P, et al. (2008) PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release. Science 322: 1392–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haagsma AC, Abdillahi-Ibrahim R, Wagner MJ, Krab K, Vergauwen K, et al. (2009) Selectivity of TMC207 towards mycobacterial ATP synthase compared with that towards the eukaryotic homologue. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53: 1290–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hurdle JG, Lee RB, Budha NR, Carson EI, Qi J, et al. (2008) A microbiological assessment of novel nitrofuranylamides as anti-tuberculosis agents. J Antimicrob Chemother 62: 1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stover CK, Warrener P, VanDevanter DR, Sherman DR, Arain TM, et al. (2000) A small-molecule nitroimidazopyran drug candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nature 405: 962–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sonar VN, Crooks PA (2009) Synthesis and antitubercular activity of a series of hydrazone and nitrovinyl analogs derived from heterocyclic aldehydes. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 24: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams KN, Stover CK, Zhu T, Tasneen R, Tyagi S, et al. (2009) Promising antituberculosis activity of the oxazolidinone PNU-100480 relative to that of linezolid in a murine model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53: 1314–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mitchison DA (2008) A new antituberculosis drug that selectively kills nonmultiplying Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 3: 122–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown D (2007) Unfinished business: target-based drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 12: 1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL (2007) Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldman RC, Laughon BE (2009) Discovery and validation of new antitubercular compounds as potential drug leads and probes. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89: 331–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christophe T, Ewann F, Jeon HK, Cechetto J, Brodin P (2010) High-content imaging of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages: an in vitro model for tuberculosis drug discovery. Future Med Chem 2: 1283–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sundaramurthy V, Barsacchi R, Samusik N, Marsico G, Gilleron J, et al. (2013) Integration of chemical and RNAi multiparametric profiles identifies triggers of intracellular mycobacterial killing. Cell Host Microbe 13: 129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Escaich S (2010) Novel agents to inhibit microbial virulence and pathogenicity. Expert Opin Ther Pat 20: 1401–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LE (2005) Small-molecule inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Yersinia pestis. Nat Chem Biol 1: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scherr N, Muller P, Perisa D, Combaluzier B, Jeno P, et al. (2009) Survival of pathogenic mycobacteria in macrophages is mediated through autophosphorylation of protein kinase G. J Bacteriol. 191: 4546–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jayaswal S, Kamal MA, Dua R, Gupta S, Majumdar T, et al. (2010) Identification of host-dependent survival factors for intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis through an siRNA screen. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuijl C, Savage ND, Marsman M, Tuin AW, Janssen L, et al. (2007) Intracellular bacterial growth is controlled by a kinase network around PKB/AKT1. Nature 450: 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gluckman SJ (1995) Mycobacterium marinum. Clin Dermatol 13: 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cosma CL, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L (2003) The secret lives of the pathogenic mycobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 57: 641–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hagedorn M, Soldati T (2007) Flotillin and RacH modulate the intracellular immunity of Dictyostelium to Mycobacterium marinum infection. Cell Microbiol 9: 2716–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Welin A, Lerm M (2012) Inside or outside the phagosome? The controversy of the intracellular localization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 92: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soldati T, Neyrolles O (2012) Mycobacteria and the intraphagosomal environment: take it with a pinch of salt(s)! Traffic. 13: 1042–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salah IB, Ghigo E, Drancourt M (2009) Free-living amoebae, a training field for macrophage resistance of mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 15: 894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takaki K, Davis JM, Winglee K, Ramakrishnan L (2013) Evaluation of the pathogenesis and treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection in zebrafish. Nat Protoc 8: 1114–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cosson P, Soldati T (2008) Eat, kill or die: when amoeba meets bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 11: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hilbi H, Weber SS, Ragaz C, Nyfeler Y, Urwyler S (2007) Environmental predators as models for bacterial pathogenesis. Environ Microbiol 9: 563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Steinert M, Heuner K (2005) Dictyostelium as host model for pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 7: 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Greub G, Raoult D (2004) Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev 17: 413–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adekambi T, Ben Salah S, Khlif M, Raoult D, Drancourt M (2006) Survival of environmental mycobacteria in Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 5974–5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ben Salah I, Drancourt M (2010) Surviving within the amoebal exocyst: the Mycobacterium avium complex paradigm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58. Steinert M, Birkness K, White E, Fields B, Quinn F (1998) Mycobacterium avium bacilli grow saprozoically in coculture with Acanthamoeba polyphaga and survive within cyst walls. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 2256–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Miltner EC, Bermudez LE (2000) Mycobacterium avium grown in Acanthamoeba castellanii is protected from the effects of antimicrobials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44: 1990–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kennedy GM, Morisaki JH, Champion PA (2012) Conserved mechanisms of Mycobacterium marinum pathogenesis within the environmental amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 2049–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ollinger J, Bailey MA, Moraski GC, Casey A, Florio S, et al. (2013) A dual read-out assay to evaluate the potency of compounds active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8: e60531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Takaki K, Cosma CL, Troll MA, Ramakrishnan L (2012) An in vivo platform for rapid high-throughput antitubercular drug discovery. Cell Rep 2: 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zelmer A, Carroll P, Andreu N, Hagens K, Mahlo J, et al. (2012) A new in vivo model to test anti-tuberculosis drugs using fluorescence imaging. J Antimicrob Chemother 67: 1948–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. El-Etr SH, Subbian S, Cirillo SL, Cirillo JD (2004) Identification of two Mycobacterium marinum loci that affect interactions with macrophages. Infect Immun 72: 6902–6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ramakrishnan L, Federspiel NA, Falkow S (2000) Granuloma-specific expression of Mycobacterium virulence proteins from the glycine-rich PE-PGRS family. Science 288: 1436–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Arafah S, Kicka S, Trofimov V, Hagedorn M, Andreu N, et al. (2013) Setting up and monitoring an infection of Dictyostelium discoideum with mycobacteria. Methods Mol Biol 983: 403–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dionne MS, Ghori N, Schneider DS (2003) Drosophila melanogaster is a genetically tractable model host for Mycobacterium marinum. Infect Immun 71: 3540–3550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ramakrishnan L, Valdivia RH, McKerrow JH, Falkow S (1997) Mycobacterium marinum causes both long-term subclinical infection and acute disease in the leopard frog (Rana pipiens). Infect Immun 65: 767–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Simeone R, Bobard A, Lippmann J, Bitter W, Majlessi L, et al. (2012) Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hilbi H, Hoffmann C, Harrison CF (2011) Legionella spp. outdoors: colonization, communication and persistence. Environ Microbiol Rep 3: 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carvalho R, de Sonneville J, Stockhammer OW, Savage ND, Veneman WJ, et al. (2011) A high-throughput screen for tuberculosis progression. PLoS One 6: e16779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Baltch AL, Bopp LH, Smith RP, Michelsen PB, Ritz WJ (2005) Antibacterial activities of gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin and erythromycin against intracellular Legionella pneumophila and Legionella micdadei in human monocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother 56: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Varner TR, Bookstaver PB, Rudisill CN, Albrecht H (2011) Role of rifampin-based combination therapy for severe community-acquired Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. Ann Pharmacother 45: 967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lelong E, Marchetti A, Simon M, Burns JL, van Delden C, et al. (2011) Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in infected patients revealed in a Dictyostelium discoideum host model. Clin Microbiol Infect 17: 1415–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Froquet R, Lelong E, Marchetti A, Cosson P (2009) Dictyostelium discoideum: a model host to measure bacterial virulence. Nat Protoc 4: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR (1999) A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen 4: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pang KM, Lee E, Knecht DA (1998) Use of a fusion protein between GFP and an actin-binding domain to visualize transient filamentous-actin structures. Curr Biol 8: 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Blaschke TF, Skinner MH (1996) The clinical pharmacokinetics of rifabutin. Clin Infect Dis 22 Suppl 1S15–21 discussion S21–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hagedorn M, Rohde KH, Russell DG, Soldati T (2009) Infection by tubercular mycobacteria is spread by nonlytic ejection from their amoeba hosts. Science 323: 1729–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lee J, Remold HG, Ieong MH, Kornfeld H (2006) Macrophage apoptosis in response to high intracellular burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by a novel caspase-independent pathway. J Immunol 176: 4267–4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Butler RE, Brodin P, Jang J, Jang MS, Robertson BD, et al. (2012) The balance of apoptotic and necrotic cell death in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected macrophages is not dependent on bacterial virulence. PLoS One 7: e47573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Golstein P, Aubry L, Levraud JP (2003) Cell-death alternative model organisms: why and which? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang Y, Wade MM, Scorpio A, Zhang H, Sun Z (2003) Mode of action of pyrazinamide: disruption of Mycobacterium tuberculosis membrane transport and energetics by pyrazinoic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother 52: 790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Oh CT, Moon C, Choi TH, Kim BS, Jang J (2013) Mycobacterium marinum infection in Drosophila melanogaster for antimycobacterial activity assessment. J Antimicrob Chemother 68: 601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ahmad Z, Tyagi S, Minkowsk A, Almeida D, Nuermberger EL, et al. (2012) Activity of 5-chloro-pyrazinamide in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis. Indian J Med Res 136: 808–814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Feuerriegel S, Koser CU, Richter E, Niemann S (2013) Mycobacterium canettii is intrinsically resistant to both pyrazinamide and pyrazinoic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother 68: 1439–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, et al. (2007) An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 367–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kessler A, Schell U, Sahr T, Tiaden A, Harrison C, et al. (2013) The Legionella pneumophila orphan sensor kinase LqsT regulates competence and pathogen-host interactions as a component of the LAI-1 circuit. Environ Microbiol 15: 646–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Alibaud L, Rombouts Y, Trivelli X, Burguiere A, Cirillo SL, et al. (2011) A Mycobacterium marinum TesA mutant defective for major cell wall-associated lipids is highly attenuated in Dictyostelium discoideum and zebrafish embryos. Mol Microbiol 80: 919–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]