Abstract

The purpose of this study was to document the prevalence and to analyze morphological characteristics from hydatid cysts to test their suitability for strain identification. In the present study, 4,130 animals, including 278 cattle, 298 buffaloes, 760 sheep, 2,439 goat and 355 pigs were examined for the presence of hydatid cysts on post-mortem inspection at different slaughter houses/shops in northern India. Morphological characteristics from hydatid cysts were analyzed to test their suitability for strain identification. For statistical analysis, five variables were considered: number of hooks per rostellum, blade length of large and small hooks, and total length of large and small hooks. Principal component analysis was applied for analysis of morphological parameters. Out of a total of 4,130 animals examined, 66 were positive for hydatid cysts (prevalence 1.598 %). The prevalence of hydatid cysts was highest in cattle (5.39 %) followed by buffaloes (4.36 %), pigs (3.09 %), sheep (2.23 %) and goat (.41 %). The results indicate significant prevalence of hydatidosis in all the food producing animals and further that morphological analysis can also be used as a valid criterion for differentiation of different strains of E. granulosus particularly in developing countries where molecular studies could not be performed due to lack of infrastructure or financial constraints.

Keywords: E. granulosus, Prevalence, Rostellar hook morphology, Different strains, India

Introduction

Echinococcosis is an important medical, veterinary and economic concern in India. The public health and economic significance of echinococcosis as the most important of the cestode zoonoses, have resulted, particularly in the case of E. granulosus, in the widespread global perpetuation of Echinococcus in a variety of domestic, man-made life-cycle patterns (Eckert 1998; Schantz et al. 1995). Although the disease in domestic animals is usually asymptomatic and detected only at the time of post mortem inspection at the abattoir, it causes great economic loss through condemnation of infected offal, in particular liver. Surveys of prevalence of echinococcosis in livestock are important for comparing transmission levels quantitatively within and between regions, and for determining the significance of each species of animal in the transmission dynamics.

The recognition of strain variation is a major pre-requisite for strategic control efforts aimed at limiting transmission in an endemic area. A number of intraspecific variants or strains are known to occur within the species E. granulosus (Eckert and Thompson 1995). Variation in the pathogenicity of strains/species of Echinococcus will influence the prognosis in patients with echinococcosis. Gordo and Bandera (1997) demonstrated that morphological characteristics can also be used as a valid criterion for strain identification. Despite the strong evidence to show the endemicity of these serious zoonoses, documentation and surveillance data concerning to the prevalence and risk factors associated with zoonotic parasites in India is largely lacking. There is an urgent need for more recent parasite data to be obtained. In Indian scenario, the conditions for the establishment and transmission of hydatidosis in both livestock and humans are very ideal. The purpose of this study was to document the prevalence and to analyze morphological characteristics from hydatid cysts to test their suitability for strain identification.

Materials and methods

Sampling design and collection of hydatid material

In this experiment, 4,130 animals, including 278 cattle, 298 buffaloes, 760 sheep, 2,439 goat and 355 pigs were examined for the presence of hydatid cysts on post-mortem inspection at different slaughter houses/shops in northern India. Samples for investigating hydatidosis of food animals were collected from a Municipal Corporation slaughter house Ludhiana, private (individual) butchers’ places at Ludhiana and Saharanpur, or where livestock are slaughtered and Post Mortem Halls at Ludhiana and Ladhowal. Due to ban on cow slaughter on religious beliefs and lack of organized buffalo slaughter houses, the animals dyeing of naturally/any other disease were also included in the study. The visceral organs of every animal included in the survey were examined visually, palpated and incised for the detection of hydatid cysts at post-mortem inspection. Infected organs for hydatid cyst were collected in plastic bags for further laboratory examination. The infected visceral organs were separated from the carcass to note the size and number of hydatid cysts present. Intact hydatid cysts recovered from the infected animals were placed separately in the polythene bags containing ice and were further processed. Epidemiological data related to each animal were collected. The effect of geographical area, age, breed and sex on prevalence of infection was studied.

Morphological studies

Morphological studies were carried out as per the mentioned methods (Hobbs et al. 1990). In the laboratory, the cysts were examined to differentiate the fertile (containing protoscolices) and sterile (without protoscolices) cysts under the microscope. The materials which looked like cysts but did not fit the above criteria were discarded. Hydatid fluid was aseptically collected from each hydatid cyst using sterile disposable syringes and was collected in glass collecting tubes. The fluid was further subjected to centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 min and the sediment was observed under the low power objective of a compound microscope for protoscoleces. The sediment was examined under microscope at 100 and 400 magnifications to detect the presence/absence of the protoscoleces so as to determine fertility/sterility of the cysts. Organ-wise prevalence of sterile and fertile hydatid cysts recovered from animals was recorded. The remaining cyst and fluid materials were sterilized by formalin and were discarded.

Thirty protoscoleces per sample were analysed for the total number of rostellar hooks and ten protoscoleces per sample for hook measurements. Measurements of the total length and blade length were made on four large and four small hooks per rostellum from each of the ten protoscoleces from each sample (Hobbs et al. 1990). Protoscoleces were mounted and sufficient pressure was applied to the coverslip to cause the hooks to lie flat. For statistical analysis, five variables were considered: number of hooks per rostellum (NUH), blade length of large (LHBL) and small (SHBL) hooks, and total length of large (LHTL) and small (SHTL) hooks. Principal component analysis was performed on five samples from each intermediate species (cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat and pigs). To better explain the results, data from five horse samples mentioned by Gordo and Bandera (1997) were also included in the PCA analysis. Studies on morphology and dimensions of the different protoscoleces were made using software DPZ-BSW (OLYMPUS). For confirmation of the morphological analysis, DNA sequencing was performed in both the directions for identification of different strains of E. granulosus.

Molecular confirmation

Strains of E. granulosus were confirmed by PCR followed by sequencing of nine representative samples (Singh et al. 2012) from the morphological analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 2001). Principal component analysis was applied for analysis of morphological parameters.

Results

Out of a total of 4,130 animals examined, 66 were positive for hydatid (Fig. 1) cysts (prevalence 1.598 %). The prevalence of hydatid cysts was highest in cattle (5.39 %) followed by buffaloes (4.36 %), pigs (3.09 %), sheep (2.23 %) and goat (.41 %). The majority of individual animals harboured multiple hydatid cysts within liver and lungs except few cases where single unilocular cyst was recorded in liver or lung. Irrespective of host species, liver (49.66 %) and lungs (36.179 %) were found to be most common predilection sites for the parasites followed by spleen (13.93 %), and heart in one sheep (.224 %). The average intensity of hydatid cysts per infected carcase was found to be highest in pigs (18.64), followed by cattle (7.26), buffaloes (4.69), sheep (2.88), and goat (2.1).

Fig. 1.

Hydatid cysts recovered from lung of the cow

Morphological analysis

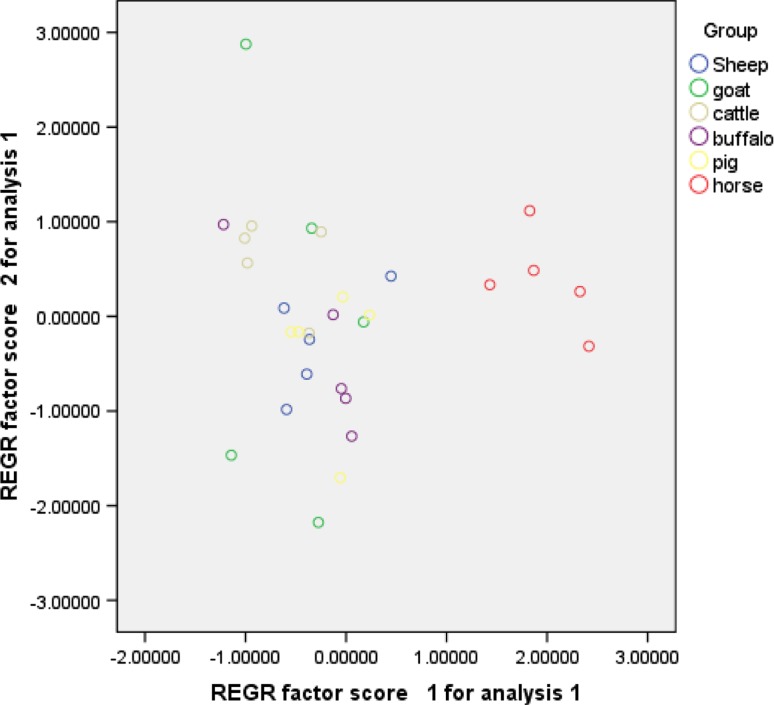

The arrangement of hooks in rostella was alternate with large and small hooks in two rows in all the samples and the shape of the hooks was smooth in their outline. The other characteristics (total number of hooks, total and blade length of large hooks, total and blade length of small hooks) are mentioned (Figs. 2, 3) in Table 1. Strong positive correlations were found between LHTL, LHBL with NUH (.247, .345) whereas very weak/no correlation was found (Table 2) between LHTL, LHBL with SHBL (.0, .009). In PCA, criteria considered for determining the number of factors to extract were the factors having Eigen value >1.0. Factor 1 and 2 represented 70 % of the variance (Table 3). If the second factor (explaining nearly 25 % of total population variance) is considered, then the first factor represented LHTL, LHBL, SHTL while the second factor represented SHBL (Table 4). When samples were plotted with both factors, two different groups were observed: the first corresponding to samples from all the intermediate species in this study (Fig. 4); a second group corresponding to horse samples taken from Gordo and Bandera (1997) belonging to horse strain of E. granulosus.

Fig. 2.

Mature invaginative protoscolex at ×40

Fig. 3.

Total, guard and blade length of large hooks at ×100

Table 1.

Rostellar hook characteristics of the protoscolices from food producing animals

| Name of the animal | Number of hooks | Arrangement of hooks | Large hooks | Small hooks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length | Blade length | Total length | Blade length | |||

| Sheep | 32–37 | Alternate small and large hooks in 2 rows | 23.2–26.3 | 11.9–13.8 | 20–24.0 | 8.0–9.6 |

| Goat | 32–36 | 23.5–26.0 | 12.0–13.2 | 20.4–22.8 | 8.0–11.5 | |

| Cattle | 32–35 | 23.8–25.0 | 12.0–13.4 | 20–22 | 8.5–9.5 | |

| Buffalo | 32–36 | 23.8–25.4 | 12.0–13.8 | 20–22.4 | 8.5–9.6 | |

| Pig | 32–36 | 24.0–26.5 | 12.5–13.5 | 20.6–22.5 | 8.5–9.6 | |

Table 2.

Correlation matrices from the five variables considered using data from 30 animal samples

| NUH | LHTL | LHBL | SHTL | SHBL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig. (1-tailed) | |||||

| NUH | .247 | .345 | .061 | .075 | |

| LHTL | .247 | .003 | .000 | .228 | |

| LHBL | .345 | .003 | .009 | .139 | |

| SHTL | .061 | .000 | .009 | .270 | |

| SHBL | .075 | .228 | .139 | .270 | |

a. Determinant = .097 indicating acceptability to proceed with the PCA as very low determinant (eg. 0.001 or so) could suggest an indication of singularity, which implies multicollinearity in the data

Table 3.

Percentage of total variance explained by five possible factors, using 30 animal samples

| Component | Initial Eigen values | Rotation sums of squared loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 2.383 | 47.654 | 47.654 | 2.235 | 44.698 | 44.698 |

| 2 | 1.137 | 22.737 | 70.391 | 1.285 | 25.693 | 70.391 |

| 3 | .830 | 16.610 | 87.000 | |||

| 4 | .575 | 11.496 | 98.497 | |||

| 5 | .075 | 1.503 | 100.000 | |||

Table 4.

Component score coefficient matrix resulting from principal component analysis, rotated (varimax), factor inter correlation −.84

| Component | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| NUH | .060 | −.628 |

| LHTL | .444 | −.102 |

| LHBL | .305 | −.006 |

| SHTL | .417 | −.022 |

| SHBL | −.084 | .648 |

Fig. 4.

Plot of 30 animal samples of E. granulosus for the two factors extracted by principal component analysis, rotated (varimax) solution

Molecular confirmation

The results of molecular analysis from these samples also indicated that these samples belonged to G3 and G1 strain of E. granulosus (Singh et al. 2012; Singh 2011). The strains G1 and G3 have been nominated as E. granulosus sensu stricto recently. In the present study, the results of statistical analysis conducted on the morphology data was similar with the results obtained from genetic analysis.

Discussion

The analysis of data generated during the present study revealed that hydatidosis is common in all the food producing animals in north India. The prevalence in cattle and buffalo was at par where as low prevalence was noticed in pigs and sheep than earlier studies in India (Pednekar et al. 2009). Irrespective of the species, the disease was found to be positively correlated with increase in age indicating that no cross immunity occurs with increase in age. In pigs, the disease was high in stray pigs than farm pigs with high relative risk indicating there easy access to dog’s faeces.

The results were in parity with many workers (Yildiz and Gurcan 2009; Williams and Sweatman 1963; Thompson et al. 1984; Kumaratilake et al. 1986) who found similar morphological values in sheep samples. Similar morphological findings were also recorded in the neighbourhood in west Punjab (Pakistan) (Hussain et al. 2005) indicating that similar G1 and G3 strains might also be prevalent in that area.

Conclusions

The results support earlier studies suggesting that hydatidosis is common in all the food producing animals in India. The results indicate that morphological analysis can be used as a valid criterion for differentiation of different strains of E. granulosus particularly in developing countries where molecular studies could not be performed due to lack of infrastructure or financial constraints.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Department of Veterinary Public Health, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary & Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, Punjab (India).

Conflict of interest

No financial or personal relationships between the authors and other people or organizations have inappropriately influenced (bias) this study.

References

- Eckert J (1998) Alveolar echinococcosis (Echinococcus multilocularis) and other forms of echinococcosis (E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus). In: Palmer SR, Soulsby EJL, Simpson DIH (eds) Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 689–716

- Eckert J, Thompson RCA (1995) Echinococcus spp.: biology and strain variation. In: Ruiz A, Schantz P, Arámbulo III P (eds) Proc. Scientific Working Group on the advances in the prevention, control and treatment of hydatidosis. 26–28 October 1994, Montevideo. Pan American Health Organization, Washington, DC, pp 29–47

- Gordo FP, Bandera CC. Differentiation of spanish strains of Echinococcus granulosus using larval rostellar hook morphometry. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(96)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RP, Lymbery AJ, Thompson RCA. Rostellar hook morphology of Echinococcus granulosus (Batsch, 1786) from natural and experimental Australian hosts and its implications for strain recognition. Parasitology. 1990;101:273–281. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000063332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A, Maqbool A, Akhtar T, Anees A. Studies on morphology of Echinococcus granulosus from different animal dog origin. Punjab Univ J Zool. 2005;20(2):151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaratilake LM, Thompson RCA, Eckert J. Echinococcus granulosus of equine origin from different countries possesses uniform morphological characteristics. Int J Parasitol. 1986;16:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(86)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pednekar PR, Gatne LM, Thompson RCA, Traub RJ. Molecular and morphological characterisation of Echinococcus from food producing animals in India. Vet Parasitol. 2009;165:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantz PM, Chai J, Craig PS, Eckert J, Jenkins DJ, Macpherson CNL, Thakur A. Epidemiology and control of hydatid disease. In: Thompson RCA, Lymbery AJ, editors. Echinococcus and hydatid disease. Wallingford: CAB International; 1995. pp. 233–331. [Google Scholar]

- Singh BB (2011) Molecular epidemiology of echinococcosis in northern India and its public health significance. Dissertation, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary & Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana

- Singh BB, Sharma JK, Ghatak S, Sharma R, Bal MS, Tuli A, Gill JPS. Molecular epidemiology of Echinococcosis from food producing animals in north India. Vet Parasitol. 2012;186(3–4):503–506. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS for Windows, Rel. 11.0.1 (2001) Chicago: SPSS Inc

- Thompson RCA, Kumaratilake LM, Eckert J. Observations on Echinococcus granulosus of cattle origin in Switzerland. Int J Parasitol. 1984;14:283–291. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(84)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, Sweatman GK. On the transmission biology and morphology of Echinococcus granulosus equines, a new subspecies of hydatid tapeworm in horses in Great Britain. Parasitology. 1963;53:391–407. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000073844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz K, Gurcan IS. The detection of Echinococcus granulosus strains using larval rostellar hook morphometry. Türkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi. 2009;33(2):199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]