Abstract

Coenzyme Qn (ubiquinone or Qn) is a redox active lipid composed of a fully substituted benzoquinone ring and a polyisoprenoid tail of n isoprene units. Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq1-coq9 mutants have defects in Q biosynthesis, lack Q6, are respiratory defective, and sensitive to stress imposed by polyunsaturated fatty acids. The hallmark phenotype of the Q-less yeast coq mutants is that respiration in isolated mitochondria can be rescued by the addition of Q2, a soluble Q analog. Yeast coq10 mutants share each of these phenotypes, with the surprising exception that they continue to produce Q6. Structure determination of the Caulobacter crescentus Coq10 homolog (CC1736) revealed a steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer (START) domain, a hydrophobic tunnel known to bind specific lipids in other START domain family members. Here we show that purified CC1736 binds Q2, Q3, Q10, or demethoxy-Q3 in an equimolar ratio, but fails to bind 3-farnesyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, a farnesylated analog of an early Q-intermediate. Over-expression of C. crescentus CC1736 or COQ8 restores respiratory electron transport and antioxidant function of Q6 in the yeast coq10 null mutant. Studies with stable isotope ring precursors of Q reveal that early Q-biosynthetic intermediates accumulate in the coq10 mutant and de novo Q-biosynthesis is less efficient than in the wild-type yeast or rescued coq10 mutant. The results suggest that the Coq10 polypeptide:Q (protein:ligand) complex may serve essential functions in facilitating de novo Q biosynthesis and in delivering newly synthesized Q to one or more complexes of the respiratory electron transport chain.

Keywords: Ubiquinone, yeast mitochondria, lipid binding, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, respiratory electron transport, lipid autoxidation

1. Introduction

Coenzyme Q (ubiquinone or Q)6 is a small lipophilic electron carrier found primarily in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it plays a key role in respiratory electron transport [1]. Q consists of a polyisoprenoid ‘tail’ whose length is species dependent and a fully substituted redox-active benzoquinone ‘head’ [2]. The reduced or hydroquinone form, QH2, also serves as a lipid soluble chain-terminating antioxidant [3]. Yeast mutants lacking Q and QH2 are sensitive to oxidative stress induced by treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids [4]. The toxicity of polyunsaturated fatty acid autoxidation products can be abrogated by substitution of the fatty acid bis-allylic hydrogen atoms with deuterium atoms [5].

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Q6 biosynthesis occurs in the mitochondria and is dependent on eleven known proteins, Coq1p-Coq9p, Yah1p, and Arh1p [6-8]. The yeast coq1-coq9 mutants lack Q, are respiratory defective and unable to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources. YAH1 and ARH1 genes encode ferrodoxin and ferredoxin reductase, are essential for yeast viability, and play roles in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis in addition to Q biosynthesis [7, 9].

An additional protein, Coq10p, is required for Q6 activity in the electron transport chain but is not essential for Q biosynthesis [10]. S. cerevisiae coq10 null mutants contain wild-type levels of Q6 but are nonetheless respiration defective. Mitochondria isolated from coq10 mutants show greatly impaired oxidation of substrates of electron transport as measured by oxygen consumption unless supplemented with exogenous Q2 [10]. This rescue of respiratory electron transport by addition of Q2 is a hallmark phenotype of the coq mutants. Thus, while yeast coq1-coq9 mutants are “Q-less”, the coq10 mutant contains Q6 but its respiratory defects are nevertheless rescued when a soluble analog of Q (such as Q2) is added. The coq10 null mutant in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe displays similar phenotypes as it produces endogenous Q10 but fails to respire as measured by oxygen consumption [11].

How Coq10p mediates Q-dependent respiratory electron transport is still mysterious. Stoichiometric considerations suggest that Coq10p is unlikely to play a direct role in shuttling Q between the respiratory complexes, because Coq10p content is three orders of magnitude less abundant than Q6 and two orders of magnitude less abundant than other respiratory chain components, such as the bc1 complex [10]. Yeast respiratory super complexes (as assayed by high molecular mass cytochrome b) were detectable but greatly decreased in the coq10 mutant relative to that of wild-type yeast [12]. Thus, while it is possible that Coq10p transports or shuttles Q6 or Q10 to the respiratory chain complexes [11], it may also serve to escort or chaperone Q to sites within the respiratory chain complexes that are critical for the Q cycle. It seems likely that Q6 can access the P-site of the bc1 complex without Coq10p because treatment of coq10 mutant mitochondria with antimycin A induces H2O2 production [12]. While this response to antimycin suggests an active Q-cycle, the bc1 complex is not functional since electrons are not transferred to cytochrome c1. Treatment of coq10 mutant mitochondria with myxothiazol failed to induce H2O2 production, consistent with a defect in residence and/or function of Q6 at the bc1 complex [12], perhaps at the N-site.

Coq10p homologs are present in a variety of organisms, from bacteria to humans [10]. Expression of the human COQ10 homolog in coq10 null mutants of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe restored growth on non-fermentable carbon sources [10, 11]. The primary sequence of Coq10p does not share homology with any protein domains of known function and is classified as part of the aromatic-rich protein family Pfam03654 [13]. The structure of the Caulobacter crescentus Coq10p homolog CC1736 was determined by NMR [14] and revealed a structure similar to that of the steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer (START) domain, which is known to bind lipids such as cholesterol or polyketides via a hydrophobic tunnel [15, 16]. The START domain structure is classified as a helix-grip type, consisting of a seven-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet with a C-terminal α-helix [17]. Purification of S. cerevisiae Coq10p indicates that it binds endogenous Q6, but as purified from yeast the content of Q6 was substoichiometric [10]. Studies with S. pombe Coq10p indicate that this protein binds Q10 at an equimolar ratio of ligand to protein and that this binding depends on conserved hydrophobic amino acids [11], as shown via multiple sequence alignment (Fig. 1). Point mutation analyses and molecular modeling studies suggest that S. cerevisiae Coq10p likely contains a similar hydrophobic tunnel capable of binding lipid substrates [18]. One postulated function of Q binding by CC1736 and by extension Coq10p may be to chaperone Q to its proper locations in the respiratory chain complexes.

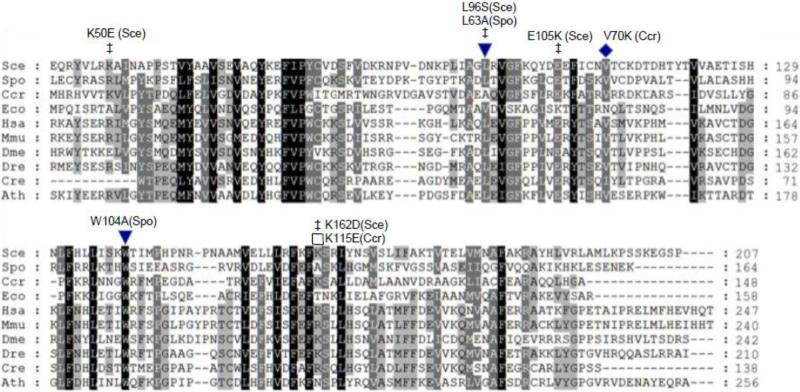

Figure 1.

Conserved amino acid residues in Coq10 polypeptide homologues. Protein sequences were aligned with BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA) and shaded as described by Genedoc with three levels of shading (http://www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc/) [54]. Residues conserved in all proteins are shaded black, in 80% dark grey, and in 60% light grey. Amino-terminal segments of eukaryotic polypeptides preceding the first methionine of the C. crescentus (Ccr) and E. coli (Eco) polypeptides are not conserved and were omitted from the alignment for clarity. Residues determined to be important for maintenance of respiration are designated with filled symbols and include C. crescentus V70K (this work), S. pombe L63A and W104A [11]. Additional mutations affecting S. cerevisiae Coq10p function are designated by ‡ and include K50E, L96S, E105K, and K162D [18]. Mutation of K115E in CC1736 (marked by an open square) did not impair rescue of the S. cerevisiae coq10 null mutant (this work). The aligned sequences include: S. cerevisiae COQ10 (NCBI GeneID: 854154), Schizosaccharomyces pombe COQ10 (942096), C. crescentus CBL5 (942096), E. coli yfjG (945614), Homo sapiens COQ10A (93058), M. musculus COQ10B (67876), Drosophila melanogaster CG9410 (35568), Danio rerio Zgc:73324 (393762), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii COQ10 (5718019), and Arabidopsis thaliana AT4G17650 (827485).

Most of the Coq proteins in S. cerevisiae including Coq10p are localized to the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane [8]. Blue native-PAGE and co-precipitation experiments demonstrate that several of the Coq proteins exist in a high molecular weight complex [8, 19-21]. Additionally, the steady-state levels of several of these Coq proteins are interdependent as levels decrease significantly in various coq null mutants [20]. In contrast, steady state levels of Coq10p are not affected by other coq gene gene deletions [20]. Coq10p has not been demonstrated to interact with the other Coq proteins by co-immunoprecipitation but it was suggested to exist in an oligomeric form via sucrose gradient sedimentation [10] and was recently shown to co-migrate via BN-PAGE with Coq2p and Coq8p [22]. Coq8p contains protein kinase motifs and is required for phosphorylation of Coq3p, Coq5p, and Coq7p [23]. Although Coq8p has not been shown to exist in a macromolecular complex with other Coq proteins, it is required for the stability of several Coq proteins [20]. Over-expression of Coq8p stabilizes the steady-state levels of several Coq proteins in various coq null mutants including the coq10 null [10, 24, 25] and increases the accumulation of later stage coenzyme Q biosynthetic intermediates [25, 26]. Over-expression of Coq2p and Coq7p in the coq10 null mutant also restores growth on non-fermentable carbon sources, however the greatest effect is observed with over-expression of Coq8p [10]. Over-expression of Coq8p leads to increased levels of endogenous Q6 [10], which is thought to overcome the defect in Coq10p and allow for functional respiration. In contrast, severe over-expression (300-fold compared to wild-type yeast) of Coq10p in S. cerevisiae impairs mitochondrial respiration as observed by decreased oxygen consumption and a decreased ability to utilize non-fermentable carbon sources [24]. It was hypothesized that the respiratory defect caused by over-expression of Coq10p in S. cerevisiae is due to sequestering of the endogenous Q6 by the excess Coq10p [24]. Over-expression of Coq8p suppresses the respiratory deficiency resulting from severe over-expression of Coq10p.

Here we show that expression of the C. crescentus CC1736 START domain polypeptide in S. cerevisiae restores growth of the coq10 null mutant on non-fermentable carbon sources and functional electron transport. The content of Q6 and Q6 biosynthetic intermediates were also examined in the coq10 null mutant as well as wild type and the coq10 null over-expressing CC1736 or Coq8p. Binding studies with Q of varying tail lengths as well as Q biosynthetic intermediates were performed with purified recombinant CC1736. The results suggest that CC1736 and Coq10p bind Q and late-stage Q-intermediates, and play conserved roles in facilitating de novo Q synthesis and respiratory electron transport.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Yeast strains and growth media

Yeast strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Media were prepared as described [27], and included: YPD (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone), YPGal (2% galactose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.20% glucose), and YPG (3% glycerol, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone). Synthetic Dextrose/Minimal medium (SDC and SD–Ura) was prepared as described [28], and consisted of all components minus uracil. Drop out dextrose medium (DOD) was prepared as described [29] except that dextrose was used in place of galactose. Plate media contained 2% bacto agar.

Table 1.

Genotype and Source of Yeast Strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | R. Rothsteina |

| W303-1B | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | R. Rothsteina |

| W303ΔCOQ10 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq10::HIS3 | [10] |

| CC303 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1coq3::LEU2 | [4] |

| W303ΔCOR1 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 cor1::HIS3 | [50] |

| NM101, coq7Δ-1 | NM101, coq7Δ-1::LEU2 | [51] |

| W303ΔABC1 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 abc1/coq8::HIS3 | [52] |

| W303ΔCOQ9 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq9::URA3 | [53] |

| CC304.1 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 atp2::LEU2 | [4] |

Dr. Rodney Rothstein, Department of Human Genetics, Columbia University

2.2 Construction of multicopy yeast expression vector with the CYC1 promoter and a mitochondrial leader sequence from COQ3

Plasmids used and generated in this study are listed in Table 2. A 0.5 kb BamH1-Kpn1 fragment containing the yeast CYC1 promoter and the amino terminal mitochondrial leader sequence (residues 1 to 35) of yeast COQ3 was isolated from pQM [30]. This fragment was inserted into the BamH1 and Kpn1 sites of the multicopy yeast/E. coli shuttle vector pRS426 [31] and named pRCM.

Table 2.

Plasmids Used

| Plasmids | Relevant genes/markers | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pRS426 | Yeast Shuttle Vector; multicopy | [31] |

| pCH1 | Yeast vector with CYC1 promoter; multicopy | [30] |

| pRCM | pCH1 with COQ3 mito leader; multicopy | This work |

| p4HN4 | pRS426 with Yeast ABC1/COQ8; multicopy | [20] |

| PG140/ST3 | Yeast COQ10; multicopy | [10] |

| pRCM-CC1736 | pRCM with C. crescentus CC1736; multicopy | This work |

| pET21d | E. coli expression vector | EMD4Biosciences |

| pET21d-CC1736 | pET21d with C. crescentus CC1736 | This work |

| pRCM-K115E | pRCM with CC1736-K115E; multicopy | This work |

| pRCM-V70K | pRCM with CC1736-V70K; multicopy | This work |

2.3 Cloning of C. crescentus CC1736 in yeast expression vectors

The source plasmid pCcR19-21.1 [32], encodes the full-length CC1736 gene from C. crescentus plus eight non-native C-terminal residues (LEHHHHHH) cloned into pET21d (Novagen derivative). A segment of DNA containing the CC1736 ORF was amplified from pCcR19-21.1 template DNA with the forward primer 5’-GGGGTACCATGTTGCACCGTCACGTCGTTAC-3’ (−3 to +20 bp of CC1736 underlined, with Kpn1 site bold) and the reverse complement primer 5’-GGGGTACCTTTGTTAGCAGCCGGATCTCAGT-3’ (+489 to +467 underlined, Kpn1 site bold). The resulting PCR product was digested with Kpn1 and cloned into the Kpn1 site of the yeast expression plasmids pRCM and pCH (similar to pRCM but without the Coq3 mitochondrial leader) [30], to generate pRCM-CC1736 and pCH-CC1736, respectively.

2.4 Site directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with a Quick-Change mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer's protocol. The plasmid pCcR19-21.1 provided the template for the PCR reactions, which utilized the following primers for V70K and K115E codon replacement: V70Ksense, 5’-AGAAGTTCGCGACCCGCAAACGTCGTGACAAAGACGC-3’ (the lysine codon is underlined); V70Kantisense, 5’-GCGTCTTTGTCACGACGTTTGCGGGTCGCGAACTTCT-3’ (the antisense lysine codon is underlined); K115Esense, 5’-CATCGAGTTTGCGTTCGAATCCGCGCTGCTAGACG-3’ (the glutamate codon is underlined); and K115Eantisense, 5’-CGTCTAGCAGCGCGGATTCGAACGCAAACTCGATG-3’ (the glutamate anticodon is underlined). The substitution mutations in the resulting clones, pET-CC1736V70K and pET-CC1736K115E were confirmed by sequence analyses performed by the UCLA DNA sequencing facility. The Kpn1 fragments from pET-CC1736V70K and pET-CC1736K115E were cloned into the Kpn1 site of pRCM to generate V70K-CC1736 or K115E-CC1736, respectively.

2.5 Complementation of the yeast coq10 null mutant by C. crescentus CC1736

Yeast transformations were performed as described [33]. The coq10 null mutant W303ΔCOQ10 was transformed with each of the following multi-copy plasmids: pRCM, (empty vector), p4HN4 (COQ8), pRCM-CC1736, pRCM-V70K, pRCM-K115E, or with the positive control plasmid, PG140/ST3 [10], containing yeast COQ10. Transformed yeast cells were selected on SD–Ura plate medium for 3 days at 30 °C. Colonies from these plates were grown in selective liquid medium to mid log phase (OD600nm = 0.2-1.0). An aliquot was diluted with sterile water to OD600nm = 0.2, and cells were serially diluted (1:5), and 2 μl of each sample were spotted onto SD or SD-Ura (fermentable) or YPG (non-fermentable) plate medium, and incubated at 30 °C.

2.6 Fatty acid sensitivity assays

A fatty acid sensitivity assay was used to assess relative sensitivities of different yeast mutants to oxidative stress [4]. Yeast strains were grown in YPD media at 30 °C and 250 rpm and harvested while in logarithmic phase (OD600nm per ml = 0.2-1.0). The cells were washed twice with sterile water and resuspended in 0.10 M phosphate buffer (0.2% dextrose, pH 6.2) to an optical density of 0.20 OD600nm per ml. Aliquots (20 ml) were placed in new sterile flasks (125 ml) and fatty acids were added to a final concentration of 200 μM (from stocks prepared in ethanol). Following incubation (30 °C and 250 rpm) aliquots were removed and viability was ascertained by plate dilution assays. Plate dilution assays were performed by spotting 2 μl of 1:5 serial dilutions (starting at 0.20 OD600nm /ml) onto YPD plate medium.

2.7 Live cell lipid peroxidation assay

The live cell lipid peroxidation assay was performed as described in [34]. Aliquots (10 ml) were removed from incubator (250 rpm at 30 °C) at the designated time and cells were washed twice with sterile water to remove excess fatty acids. Cells (2 OD600nm) were resuspended in 1 ml 0.10 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.2, 0.2% dextrose, and treated with a 5 μM final concentration of C11-BODIPY(581/591) (Molecular Probes). The C11-BODIPY was dissolved in ethanol and used as a 2 mM stock. After 30 min incubation at room temperature with shaking, cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 s, washed and resuspended in 1 ml 0.10 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.2, 0.2% dextrose. Aliquots (100 μl) were placed into a black, flat-bottomed 96-well plate in quadruplicates. Fluorescence was measured with a 485 nm excitation and a 520 nm emission filter in a Perkin Elmer, 1420 Multi label Counter Victor3, and data was obtained using the Wallac workstation. Cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy with an Olympus IX70 fluorescence microscope, a 100X oil objective, and using a 490 nm excitation with a 520 nm emission filter (FITC).

2.8 Preparation of mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The yeast strains were grown in selective media overnight and 1 ml of this culture was transferred to 600 ml YPGal + 0.2% dextrose and incubated with shaking (250 rpm, 30 °C). The cells were harvested at OD600nm between 2-3. The crude mitochondria were isolated as described [35], then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The protein concentration was measured with a BCA assay (Thermo Scientific).

2.9 Enzymatic Assays

NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity was measured as described in [36] with the following modifications. The assay was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the reduction of cytochrome c at an absorbance of 550 nm at 23 °C. The reaction cuvette contained phosphate buffer (6.2 mM K2HPO4/33.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.2), 0.9 mM KCN, 0.14 mM EDTA, 30 μM NADH, and 20.45 μM cytochrome c. Samples either contained ethanol as a vehicle control or 1 mM Q2, added in from a stock in ethanol. The rate of cytochrome c oxidation by yeast mitochondria was determined by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 550 nm at 30 °C. Crude mitochondria (20 μg) were resuspended in 100 μl 0.25 M sucrose and added to 1.5 ml cuvette containing 1 ml phosphate buffer (6.2 mM K2HPO4/33.8 mM KH2PO4, 0.244% Brij 30, pH 6.2) and 20.45 μM freshly reduced cytochrome c [36] in the presence or absence of 0.9 mM KCN. The sample mixture was inverted and the decrease in absorbance at 550 nm was recorded to determine the enzymatic activity using an extinction coefficient of 19.6 mM−1cm−1 [36].

2.10 Western blot analysis of His-tagged proteins

Proteins were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis on 15% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane and blocked with PBS (37 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 3% skimmed milk for one hour at room temperature. His6-tagged proteins were detected with chicken polyclonal antisera directed against the His tag and conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Abcam, ab3553). Prior to use antisera were diluted to 1:1500 in PBS containing 3% skimmed milk and 0.1% Tween 20. Rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against yeast Atp2 were diluted 1:10,000 in PBS containing 3% skimmed milk and 0.1% Tween 20 was used as a loading control. The secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to peroxidase (Calbiochem) was diluted 1:10,000 in the same solution as the primary antibody. Binding was visualized with the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

2.11 Analyses of Q6 and Q6-intermediates in wild-type and coq10 null mutant yeast

The content of Q6 and detection of Q6 intermediates was determined as described [29] with the following modifications. To monitor Q6 and Q6 intermediates during log phase growth, early-, mid-, and late-log phase growth was first determined from growth curves of W303-1A and W303ΔCOQ10 in DOD medium. Wild-type and coq10 null mutant strains showed similar values of OD600 during early-, mid-, and late-log phase culture. For labeling, yeast strains were grown overnight in SD-complete pre-cultures, which were used to inoculate 50 ml DOD medium to an OD600 of 0.05. For early-log phase, cells were labeled at an OD600 of 0.5 with 5 μg/ml 13C6-pABA, 5 μg/ml 13C6-4HB, or ethanol as a vehicle control for 5 h (250 rpm at 30 °C). Mid-log cells were labeled at an OD600 of 1.5 and late-log cells at an OD600 of 3.0 under the same conditions. Alternatively, Q6 and Q6 intermediates were monitored in in W303-1A and W303ΔCOQ10 yeast transformants at early-log phase. For these experiments, yeast strains were grown overnight in SD−Ura and diluted into 50 ml DOD−Ura media to an OD600 of 0.05. Once yeast cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5, cells were labeled with either 5 μg/ml 13C6-4HB or 5 μg/ml 13C6-pABA for 3 h (250 rpm at 30 °C). Q6 and Q6 intermediates were also monitored in concentrated cultures. For these experiments, yeast strains were inoculated overnight in selective media and diluted in 100 ml YPD media for a second overnight inoculation. Yeast cells (100 ODs) were harvested at log phase (2.0-4.0 OD600nm) and resuspended in 4 ml DOD media. Cells were incubated with either 40 μg/mL 13C6-pABA or 13C6-4HB for 2 h (250 rpm at 30 °C).

After labeling, cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min, washed twice with sterile water, and lipid extracts were prepared with a 2:1 petroleum ether:methanol extraction as described [29]. The organic phase was transferred to a new borosilicate tube, the extraction with petroleum ether repeated two times, and the pooled organic phase was concentrated under a stream of N2 gas. A Q6 standard curve was prepared concurrently and extracted alongside the yeast cell pellet samples. Lipids were resuspended in either 100 or 200 μl of ethanol.

HPLC-MS/MS analyses were performed as described [29] with the following modifications; 20 μl of each lipid extract were injected onto a Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) and the HPLC mobile phase consisted of Solvent A (methanol:isopropanol; 95:5, with 2.5 mM ammonium formate) and Solvent B (isopropanol, with 2.5 mM ammonium formate). Initial conditions were 100% Solvent A and linearly decreasing to 95% at 8 min with a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. In each sample the amount of analyte was corrected for recovery of the Q4 internal standard. Samples were analyzed using a 4000 QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Analyst 1.4.2 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for detection of Q6 and Q6 intermediates.

2.12 Induction and purification of C. crescentus CC1736 polypeptide

E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) pMgK was transformed with pCcR19-21.1 or pET-CC1736K115E. Transformants were recovered on LB + Amp + Kan plate media and then transferred to 5 ml of LB Broth Miller medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 60 μg/ml kanamycin and grown overnight with aeration (250 rpm at 37 °C). The cells were diluted in 2 L of the same medium and grown for 2-3 hours (250 rpm, 21 °C). Following incubation 1 mM IPTG was added to the culture and incubation proceeded for 16 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and then washed twice and resuspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8, 10 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5mM BME, 1 mM protease inhibitor) at 4 °C with stirring for 45 min. The cells were then lysed by sonication (Fisher Sonic Dismembrator, Model 300; 6 cycles, 45 s bursts, 45 s on ice) at 35% duty cycle. Unbroken cells and inclusion bodies were removed by centrifugation (12,400 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was applied to 8 ml Ni-NTA superflow resin column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at 4 °C. The column was washed with 12 column volumes of buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol), proceeded by a second wash with 5 column volumes of 50 mM imidazole in buffer A, and a third wash with 3 column volumes of 100 mM imidazole in buffer A. The His-tagged CC1736 polypeptide was eluted with 500 mM imidazole in buffer A (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The protein was concentrated to 1.5 ml with an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter device (10,000 MWCO, Millipore). The concentrated protein was then applied to a Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare), size exclusion column (75 × 1.5 cm), equilibrated in the mobile phase (20 mM MES, pH 6.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM TCEP, 0.1 mM dodecyl maltoside, 0.02% NaN3, pre-filtered through a 0.2 μm filter membrane) to separate the CC1736 polypeptide from other contaminating proteins.

2.13 In vitro Q-binding assay

Each binding assay contained 2-3 nmol purified C. crescentus CC1736 and 8-10 nmol cytochrome c polypeptide. The ligands tested included: Q2, Q10, and ergosterol (all from Sigma), Q3 (prepared as described [37]), demethoxy-Q3 (DMQ3, prepared as described [28]), and 3-farnesyl-4-hydroxybenzoate (FHB, prepared as described [38]). Each compound (concentration range from 0.005 to 0.27 mM) was mixed well with either CC1736 or cytochrome c in 20 mM MES buffer, pH 6.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM dodecyl maltoside, 1.0 mM TCEP, and 2% ethanol. Samples were incubated for 45 min at 30 °C and centrifuged (1300 × g, one min). The supernatant was applied to a protein-desalting–spin-column (PIERCE, catalog number 89862), pre-equilibrated with binding buffer to separate protein-bound-ligand from unbound ligand. Samples were subjected to centrifugation (1300 × g, one min) and the protein concentration was determined by the Lowry assay [39]. Prior to lipid extraction, 3 nmol of Q4 (for samples testing binding of Q2, Q3, DMQ3, or FHB) or 3 nmol Q9 (for samples testing binding of Q10 and ergosterol) was added as an internal standard to each sample (65 μl). Six calibration standards were prepared concurrently and contained the internal standard and experimental ligand over a range from 0.2 to 2.2 nmol to generate a calibration curve. Saturated sodium chloride (1 ml) and hexanes:2-propanol (v:v, 3:2) (2 ml) was added to each sample and vortex-mixed for 45 s at top speed. The organic phase was transferred to a new borosilicate tube and concentrated down under a stream of N2 gas. Lipids were resuspended in 90 μl of ethanol, and 70 μl of each lipid extract was manually injected into a reversed-phase HPLC system [40]. Samples were applied to a Luna Hexa-phenyl column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5μm) and separated with an isocratic mobile phase (1 ml/min; 88:24:10 MeOH/EtOH/2-propanol), followed by UV detection at the designated wavelength. Lipid ligands were detected by UV absorption: 275 nm for Q2, Q3, and Q10; 271 nm for DMQ3; 260 nm for FHB; and 272 nm for ergosterol. In each sample the amount of analyte was corrected for recovery of the Qn internal standard. The number of mol ligand bound: mol polypeptide, and dissociation constant of ligand was determined with the Km calculator from Graph Pad Prism.

3. Results

3.1 Expression of C. crescentus CC1736 START domain polypeptide restores respiration in the yeast coq10 mutant

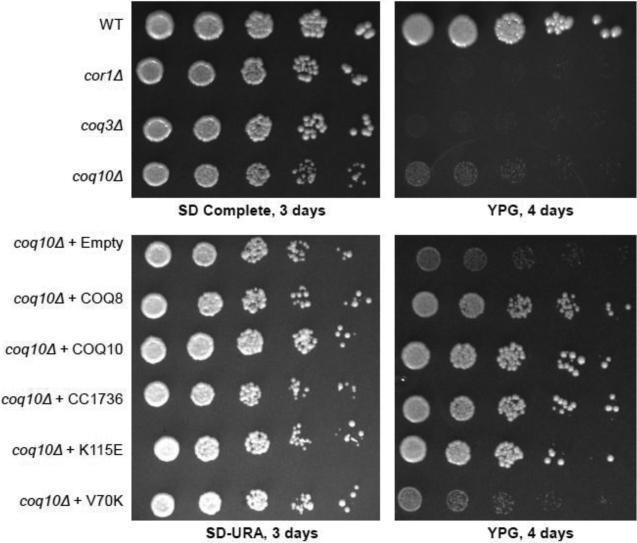

The yeast coq10 null mutant shows very slow growth on YPG medium (containing glycerol as the sole non-fermentable carbon source) (Fig. 2). This phenotype is less severe than that of other respiratory deficient mutants, such as cor1 or coq3 null yeast mutants [10]. Over-expression of the C. crescentus CC1736 START domain polypeptide (Fig. 1) harboring the 35-residue amino-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence from Coq3 [30], restores growth of the coq10 null mutant on YPG medium, comparable to that mediated by expression of yeast Coq10p or Coq8p (Fig. 2). This result identifies CC1736 polypeptide as a functional ortholog of yeast Coq10p.

Figure 2.

Complementation of a yeast coq10 null mutant by expression of C. crescentus CC1736 requires the amino acid residue V70 for respiratory function. Wild-type, respiratory deficient cor1, yeast Q-less coq3 null mutant, and the coq10 null mutant were grown in SD complete medium and harvested during mid-log phase (0.2-1.0 OD600nm). The coq10 null mutant W303ΔCOQ10 was transformed with each of the following multi-copy plasmids: Empty (pRS426), COQ8 (p4HN4), COQ10 (pG140/ST3), CC1736 (pRCM-CC1736), or with plasmids encoding CC1736 with amino acid substitutions K115E (pRCM-K115E) or V70K (pRCM-V70K). Yeast transformants were grown in selective media and harvested during mid-log phase. Cells were washed twice with sterile water and diluted to a final OD600nm of 0.2. Serial dilutions (1:5) were prepared and 2 μl of each sample was spotted onto SD-Complete or SD-Ura, and rich glycerol (YPG) plate medium and incubated at 30 °C for 3 or 4 days, as indicated.

To identify residues important for function of CC1736, two amino acid substitutions were introduced, V70K and K115E. These residues are conserved among many of the Coq10 homologues (Fig. 1) and were predicted to be important for ligand binding by the START domain of CC1736 [14]. These mutations were introduced into the pRCM-CC1736 construct as described in Section 2.4. Expression of the CC1736-V70K polypeptide failed to rescue the yeast coq10 null mutant growth on glycerol, while expression of CC1736-K115E retained ability to rescue (Fig. 2).

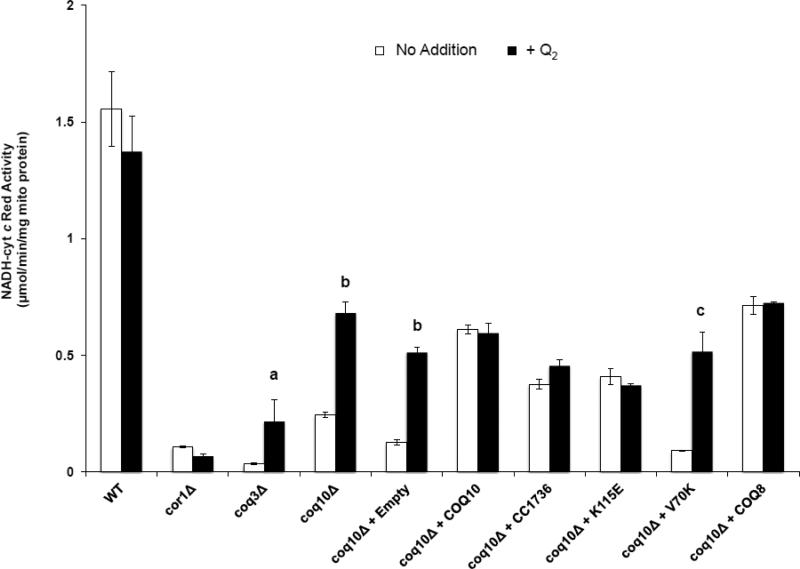

The defect in NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity in coq10 or coq3 mutant mitochondria can be partially rescued by addition of Q2 (a soluble Q analog with a tail of two isoprene units) (Fig. 3) [10]. In contrast, Q2 does not augment NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity in either wild-type yeast or the rescued coq10 strains (Fig. 3). Over-expression of Coq8p, Coq10p, or CC1736 in the coq10 null mutant provided a significant rescue of the NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity in isolated crude mitochondria (Fig. 3). Mitochondria isolated from coq10 null yeast harboring V70K, also exhibited profound defects in NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity that were rescued by Q2 (Fig. 3). Although the addition of Q2 did not restore NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity levels to that of wild type, this is likely due to the tendency of the coq10 mutant to lose mitochondrial DNA [10], and is evident from a decrease in the cytochrome c oxidase activity (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Mitochondria were isolated from wild type, respiratory deficient cor1 null mutant, Q-less coq3 null mutant, Q-replete coq10 null mutant and coq10 null mutant harboring plasmids expressing the designated proteins. NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity was determined in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of 1 μM coenzyme Q2 (performed in triplicate for each sample). NADH-cytochrome c activity of the yeast coq3 null mutant, coq10 null mutant and coq10 null mutant expressing empty vector and V70K is significantly rescued by the addition of 1 μM coenzyme Q2; a, p < 0.0175; b, p < 6.1 E−04; c, p < 3.3 E−03. Values are given as the average ± standard deviation.

Table 3.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity assay

| Cytochrome c oxidase (μmol/min/mg protein) | |

|---|---|

| W3031B | 0.652 (±0.184) |

| cor1Δ | 0.572 (±0.045) |

| coq3Δ | 0.172 (±0.019) |

| coq10Δ | 0.230 (±0.016) |

| coq10Δ + Empty | 0.288 (±0.051) |

| coq10Δ + COQ10 | 0.403 (±0.073) |

| coq10Δ + CC1736 | 0.470 (±0.066) |

| coq10Δ + K115E | 0.372 (±0.073) |

| coq10Δ + V70K | 0.184 (±0.124) |

| coq10Δ + COQ8 | 0.603 (±0.036) |

The inability of the V70K polypeptide to rescue is not due to failure of expression but may be due to the inability of being processed correctly. A western blot (Fig.S1) shows that the V70K polypeptide is not processed in the same manner as either the CC1736 wild type or K115E polypeptides. These results suggest that the V70K mutation interferes or prevents the processing of the amino terminal mitochondrial leader sequence fused to CC1736.

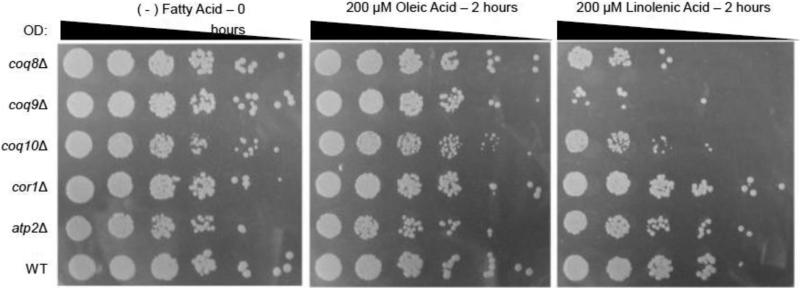

3.2 The coq10 mutant is sensitive to PUFA treatment

The yeast coq mutants are very sensitive to treatment with PUFAs, due to the lack of Q6/Q6H2 antioxidant protection [4, 41]. As shown in Fig. 4, the yeast coq8, coq9, andcoq10 mutants treated with linolenic acid (αLnn) for two hours showed higher sensitivity as compared to wild-type yeast or yeast treated with oleic acid. While the sensitivity of the coq8 and coq9 mutants to PUFA stress is predicted due to their lack of Q6, the coq10 null mutant has near normal amounts of Q6 in mitochondria [10]. The sensitivity of the coq10 null cannot be attributed to a lack of respiration per se, because the cor1 and atp2 mutants, with defects in complex III or V, respectively, remain resistant to PUFA treatment (Fig. 4). To understand the requirement of Coq10p for the antioxidant function of Q/QH2, we decided to further characterize the nature of the PUFA sensitivity of the coq10 mutant.

Figure 4.

Yeast coq8, coq9, and coq10 mutants are hypersensitive to treatment with αLnn. Yeast strains were grown in YPD media and harvested during mid-log phase (0.2-1.0 OD600nm). The cor1 and atp2 null mutants serve as respiratory deficient controls. Cells were washed twice with sterile water and resuspended in phosphate buffer to a final OD600nm of 0.2. The designated fatty acids (final concentration of 200 μM) were added to a flask containing 20 ml of yeast /phosphate buffer as described in Section 2.6. Samples were removed either before addition of fatty acids (0 hour control) or after 2 hr of incubation at 30 °C in the presence of the designated fatty acid. Serial dilutions (1:5) were prepared and 2 μl were spotted onto YPD plate medium. Images were taken after two days of growth at 30 °C.

3.3 Over-expression of Coq10p, Coq8p, or CC1736 rescues the sensitivity of the yeast coq10 null mutant to PUFA stress and suppresses accumulation of lipid peroxidation products

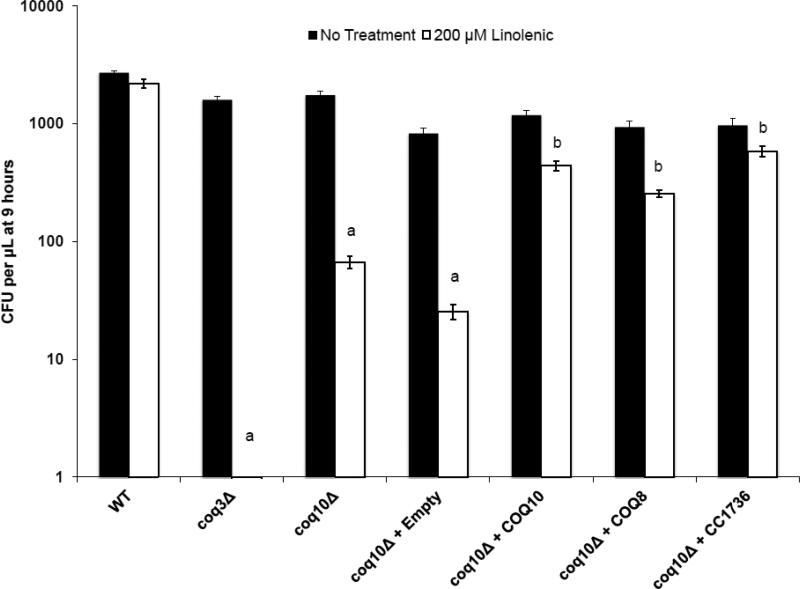

As shown in Fig. 5, αLnn stress causes a ten-fold decrease in the coq10 mutant cell viability (colony forming units or CFU) as compared to either αLnn-treated wild-type yeast or to untreated control. The CFU assay is more quantitative than the plate dilution assay, and shows that although the coq10 mutant is sensitive to PUFA treatment, it is less sensitive than the Q-less coq3 mutant. The sensitivity of the coq10 mutant to PUFA treatment is rescued by over-expression of Coq10p, Coq8p, or C. crescentus CC1736 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Yeast coq10 null mutants expressing Coq8p, Coq10p, or CC1736 are resistant to treatment with αLnn. The fatty acid sensitivity assay was performed as described in Fig. 4 except three 100 μL aliquots were removed at 9 h of either no treatment or 200 μM αLnn. Dilutions were prepared, and then spread onto SD-complete or SD−Ura plate medium. The chart shows the number of colony forming units (CFU) of untreated (black) and αLnn-treated (white) yeast cells. Yeast coq3Δ, coq10Δ, and coq10Δ null mutants harboring empty vector are profoundly sensitivity to PUFA treatment as compared to PUFA treated wild-type yeast as determined by the two-sample t test; a, p < 4.3 E−07. Yeast coq10 null mutants expressing Coq8p, Coq10p, or CC1736 are resistant to PUFA treatment as compared to coq10 null mutants expressing empty vector; b, p < 2.6 E−04.

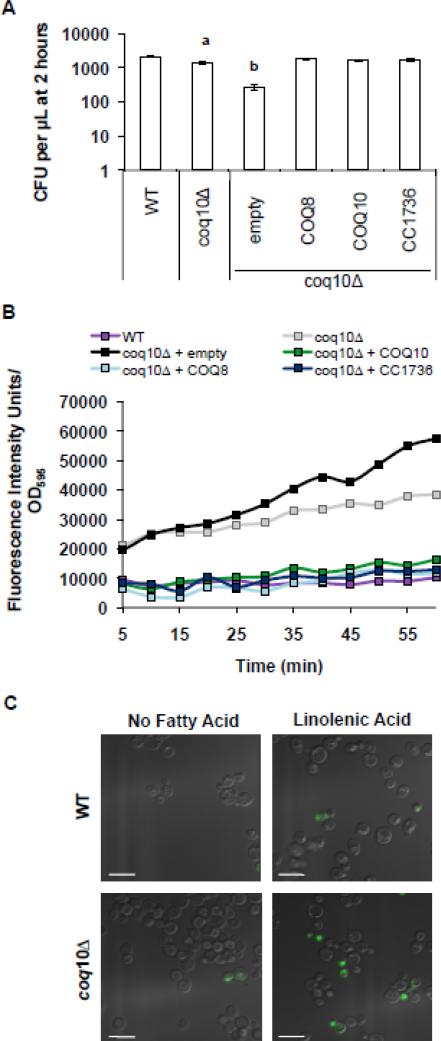

To assess the level of lipid peroxidation, yeast coq10 null mutants were treated with C11-BODIPY(581/591), a lipophilic dye that fluoresces upon oxidation by lipid peroxidation products. The oxidation of C11-BODIPY(581/591) causes a fluorescent shift from red to green and is a qualitative indicator of lipid peroxidation in living cells [42]. αLnn-treated yeast coq10 mutants showed a dramatic increase in fluorescent intensity as compared to αLnn-treated wild-type cells (Fig. 6B and C). The increased levels of lipid peroxidation in the coq10 null mutant are not due to complete loss of cell viability because after 2 hours of incubation with PUFA roughly 70% remain viable (Fig. 6A). The lipid peroxidation levels in the yeast coq10 null mutant treated with PUFA are decreased by the over-expression of Coq8p, Coq10p, or C. crescentus CC1736. These results indicate that Coq10p is required for the ability of Q to function as a lipid soluble chain-terminating antioxidant.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity of coq10 null mutant to αLnn treatment is due to increase levels of lipid peroxidation. (A) Wild-type cells were treated with αLnn for 2 hours and three 100 μl aliquots were removed and spread onto YPD plates after dilution. The chart shows the CFU per μl. (B) Following αLnn treatment, yeast cells were treated with 10 μM C11-Bodipy 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Four 100 μl aliquots were plated in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured by fluorimetry. (C) Lipid peroxidation within cells was examined as described in (B) except cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy. Green fluorescence indicates increased levels of lipid peroxidation. Scale bar = 6.6 μm.

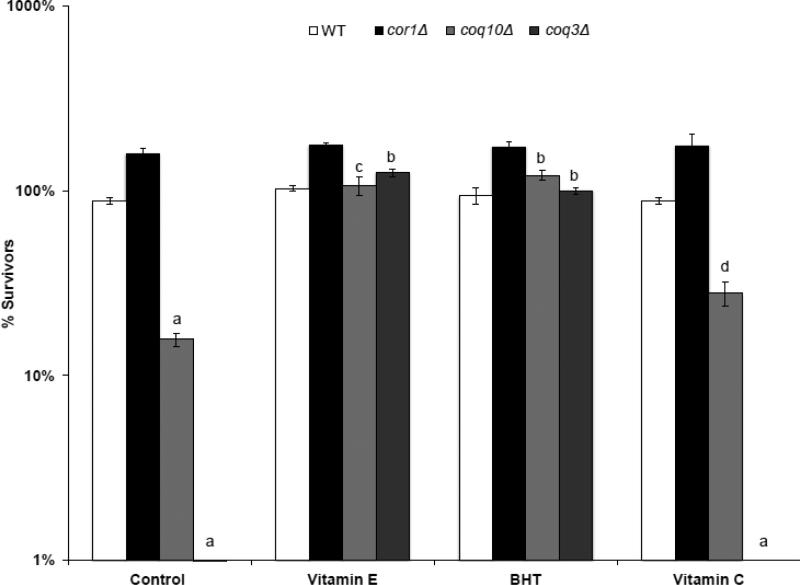

3.4 The coq10 mutant sensitivity to PUFA treatment is rescued by antioxidants

Previous studies have shown that the PUFA sensitivity of the Q-less coq mutants can be rescued by the addition of lipid soluble chain terminating antioxidants, such as vitamin E and BHT [4, 5]. The sensitivity of the yeast coq10 null mutants is also fully rescued by the addition of these lipid soluble antioxidants (Fig. 7). This rescue of PUFA sensitivity in the coq10 mutant demonstrates that the function of Q as a lipid chain-terminating antioxidant depends on the presence of the Coq10p polypeptide. Interestingly, the water-soluble antioxidant vitamin C failed to rescue the αLnn hypersensitivity of the coq3 null mutant (Fig. 7). However, vitamin C provides partial but significant rescue to coq10 null mutant αLnn sensitivity. These results suggest that vitamin C may function to regenerate the Q6H2 hydroquinone in the coq10 mutant and partially restore the ability of Q to function as an antioxidant.

Figure 7.

Treatment of yeast coq10 null mutants with BHT, vitamin E, or vitamin C rescues the αLnn toxicity. The fatty acid sensitivity assay and statistical analyses were as described for Fig. 4, except yeast were treated with designated antioxidant compounds prior to the addition of αLnn. Three 100 μL aliquots were removed at 4 h, and following dilution, spread onto YPD plates. Cell viability was assessed by colony count. Yeast strains include wild type (white), cor1 (black), coq10 (light gray), or coq3 (dark gray). In the absence of antioxidants, the number of surviving αLnn treated coq3 and coq10 null mutant cells is significantly lower as compared to wild type and cor1 null mutants (a, p < 3.1 E−05). In the presence of lipid soluble antioxidants, the number of surviving αLnn treated coq3 and coq10 null mutant cells is significantly higher as compared to no antioxidant treatment (b, p < 2 E−05, c, p < 2.2 E−04). The water-soluble antioxidant, vitamin C failed to rescue coq3 mutant cells hypersensitivity to αLnn treatment (a, p < 3.1 E−05). In contrast, vitamin C afforded partial protection of the coq10 mutant cells hypersensitivity to αLnn treatment (d, p < 8 E−03).

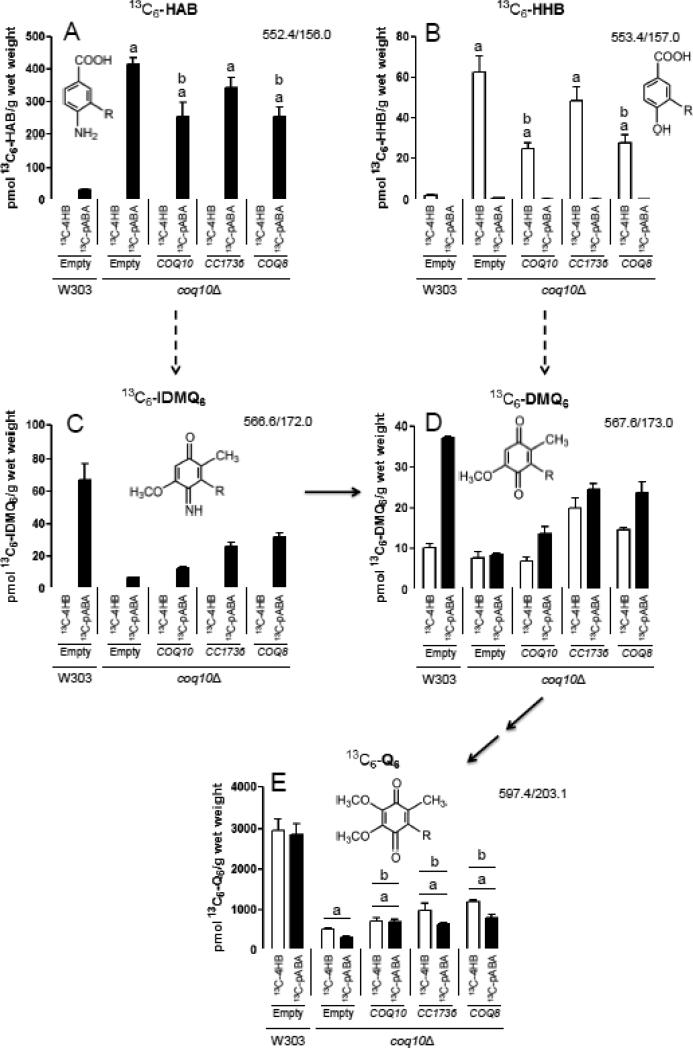

3.5 Yeast coq10 null mutants accumulate coenzyme Q intermediates and show decreased de novo synthesis of Q6

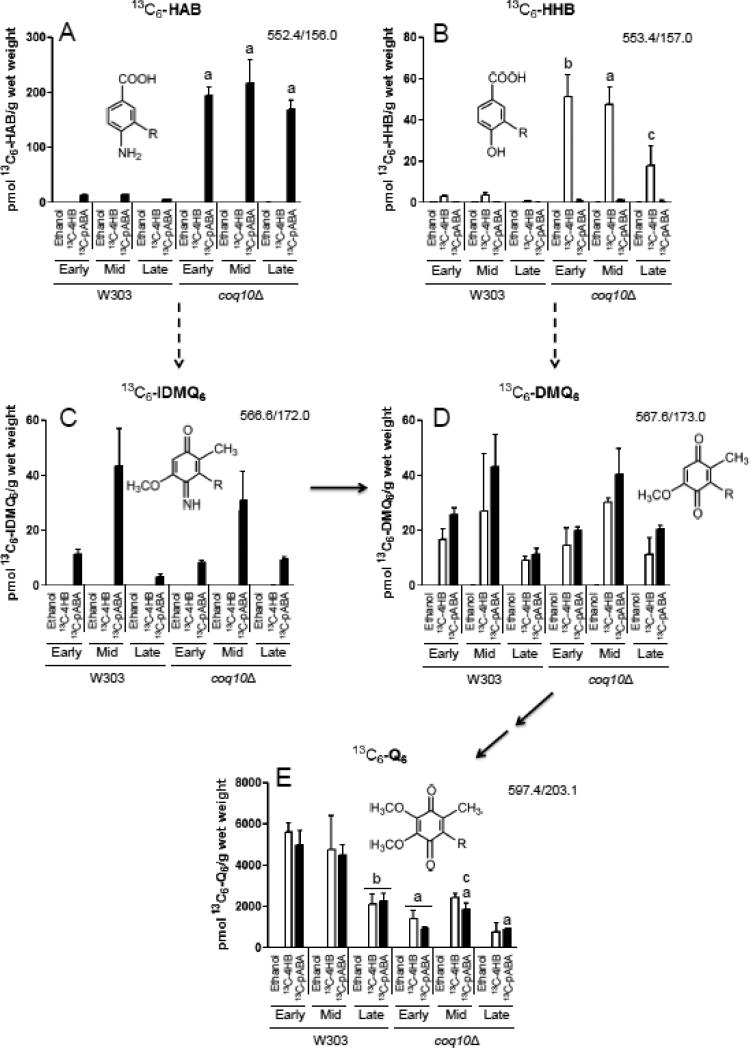

Previous studies have shown that the yeast coq10 null mutant mitochondria, when isolated from early stationary phase cultures in YPGal medium, contain near normal levels of Q6 relative to wild-type yeast [10]. To determine the efficiency of de novo Q6 biosynthesis, yeast coq10 null mutants were labeled with either 13C6-pABA or 13C6-4HB, two aromatic ring precursors of Q biosynthesis (Fig. 8). Incorporation of 13C6-ring precursors into de novo Q6 decreased as a function of growth phase in the wild type, with the greatest incorporation occurring at early-log phase and the lowest at late-log phase. In contrast de novo Q6 synthesis in the coq10 null mutant, while lower than wild type at early-log phase, did not further decrease as cells progressed to mid- or late-log phase (Fig. 8E). At early log phase, the yeast coq10 null mutant incorporates nearly 80% less of either of the aromatic ring precursors into 13C6-Q6 as compared to wild type, indicating that Q-biosynthesis in the coq10 null mutant is impaired (Fig. 8E). At late log phase, the difference between the coq10 null and wild-type cells is less dramatic, but the trend of impaired de novo Q6 biosynthesis in the coq10 null mutant is still readily apparent. Unlabeled 12C-Q6 content displayed a similar trend, decreasing in wild type as cells progressed from early- to late-log phase, while remaining relatively constant in the coq10 null mutant independent of growth phase (Fig. S2E). The addition of ring precursors boosted the total content of Q6, an effect that was more dramatic in the wild-type as compared to the coq10 mutant cells. These results indicate that the coq10 mutant has impaired Q6 biosynthesis and a lower content of Q6, and these defects are most obvious when the measurements are performed on cells during early log phase growth.

Figure 8.

Yeast coq10 null mutants have decreased de novo synthesis of 13C6-labeled Q6 compared to wild type, most notably during early-log phase growth. Wild-type and coq10 null yeast strains were cultured in SD-complete medium overnight and diluted to an OD600nm of 0.05 in DOD-complete medium. Ethanol (vehicle-control), 13C6-4HB (white bars), or 13C6-pABA (black bars) were added to yeast cultures at an OD600nm of 0.5 (early-log phase), 1.5 (late-log phase), or 3.0 (late-log phase). Prior to lipid extraction a known amount of Q4 was added as an internal standard to each sample and to the Q6 calibration standards. 13C6-labeled precursor-to-product ion transitions are as follows: (A) 13C6-HAB, 552.4/156.0; (B) 13C6-HHB, 553.4/157.0; (C) 13C6-IDMQ6, 566.6/172.0; (D) 13C6-DMQ6, 567.6/173.0; (E) 13C6-Q6, 597.4/203.1. Dashed arrows leading from HAB to IDMQ6 and from HHB to DMQ6 indicate multiple steps of Q biosynthesis (requiring Coq3, Coq4, Coq5, and Coq6). Solid arrows indicate the deimination of IDMQ6 to DMQ6 (requiring Coq9), and the final two steps converting DMQ6 to Q6 (requiring Coq7 and Coq3). Error bars depict the average ± standard deviation (n=4). (The total content of Q6 and Q6-intermediates (13C6-labeled + unlabeled), is depicted in Fig. S2). Statistical significance between pairs of samples was determined with the Student's t-test and lower-case letters above bars are indicative of statistical significance. In (A) and (B) the relative content of 13C6-labeled HAB or HHB in the coq10 null during early-, mid-, or late-log phase growth were compared to the corresponding growth phase of the wild type (a, p < 0.0001; b, p = 0.0001; c, p = 0.0112). The significance level α was adjusted to 0.0167 according to the Bonferroni correction for both (A) and (B). In (E) the content of 13C6-labeled Q6 in the coq10 null during early-, mid-, or late-log phase growth was compared to amounts present in the corresponding growth phase of the wild type (a, p ≤ 0.0004). Additionally 13C6-labeled Q6 in mid- and late-log phase was compared to early-log phase for both wild type and the coq10 null. Labeled 13C6-Q6 in wild type at late-log phase was significantly different compared to early-log phase (b, p ≤ 0.0004), and labeled Q6 in the coq10 null in mid-log phase was significantly different compared to early-log phase (c, p = 0.0008 for 13C6-pABA). For all analyses in (E) the significance level α was adjusted to 0.0033 according to the Bonferroni correction.

The low content of newly synthesized Q6 in the coq10 null mutant suggested that Q6-intermediates might accumulate in this mutant. To determine this, the lipid extracts were examined for the presence of 13C6-Q6 intermediates. The relative amounts of early (HAB and HHB), and late stage (IDMQ6 and DMQ6) intermediates are shown in Fig. 8 (panels A-D). These values are an approximation because the chemical standards required to quantify their detection by mass spectrometry are not available. However, the relative amounts can be compared. Relative to wild-type cells, the yeast coq10 null mutant accumulates high levels of early Q6-intermediates (13C6-HHB and 13C6-HAB), and both the 12C- (Fig. S2) and 13C6-compounds (Fig. 8A and B) are detected.

The respiratory deficiency and PUFA sensitivity of the coq10 null mutant is rescued by over-expression of Coq8p, CC1736, or Coq10p. To examine whether such over-expression rescues the defect in de novo Q synthesis, coq10 transformants were incubated with the 13C6-4HB and 13C6-pABA ring precursors for 3 h during early log phase growth. Over-expression of Coq8p in the coq10 null mutant increased the amount of de novo synthesized 13C6-Q6 by more than 130% as compared to the coq10 null mutant harboring empty vector (Fig. 9E and Fig. S3). Similarly, over-expression of CC1736 in the coq10 null mutant increased the content of de novo synthesized 13C6-Q6 by more than 90%. While, over-expression of Coq10p increased the content of newly synthesized 13C6-Q6 from 13C6-pABA by 110%, the stimulation of synthesis in the 13C6-4HB-labeled cells was only 39% as compared to the coq10 null. While these increases in de novo Q6 content were significant, it was surprising that none of the coq10 null transformants showed restoration of newly synthesized 13C6-Q6 to wild-type levels.

Figure 9.

De novo synthesis of 13C6-Q6 in yeast coq10 null mutants is rescued upon transformation with COQ10, CC1736 or COQ8. The designated yeast strains were cultured in SD−Ura medium overnight, and diluted to an OD600nm of 0.05 in DOD−Ura medium. 13C6-4HB (white bars) or 13C6-pABA (black bars) was added to yeast cultures at an OD600nm of 0.5, corresponding to early-log phase. Lipid extraction of samples and analysis of precursor-to-product transitions was performed as described in the Fig. 8 legend. 13C6-Q6 and 13C6-labeled Q6-intermediates are shown as in Fig. 8. The bars depict the average ± standard deviation (n=4). (The total content of Q6 and Q6-intermediates (13C6-ring-labeled + unlabeled) is depicted in Fig. S3). Statistical significance between pairs of samples was determined with the Student's t-test and lower-case letters above bars are indicative of statistical significance. In (A) and (B) the relative content of 13C6-labeled HAB or HHB in each of the coq10 null transformants was compared to wild type (a, p < 0.0001). The relative content of 13C6-labeled HAB or HHB between the coq10 null with empty vector and the other coq10 null transformants was also compared (b, p ≤ 0.0003). In (A) and (B), the significance level α was adjusted to 0.005 according to the Bonferroni correction. In (E) the content of 13C6-labeled Q6 in each of the coq10 null transformants was compared to wild type (a, p < 0.0001). The relative content of 13C6-labeled Q6 between the coq10 null transformed with empty vector and the three other coq10 null transformants was also compared (b, p ≤ 0.0024). For all analyses in (E) the significance level α was adjusted to 0.005 according to the Bonferroni correction.

Thus, we performed similar labeling analyses during late log phase (Fig. S4). During late log phase over-expression of yeast Coq10p in the coq10 null mutant nearly doubles the amount of 13C6-ring precursor incorporated into 13C6-Q6 as compared to wild-type yeast, and over-expression of Coq8p in the coq10 null mutant restores the amount of de novo synthesized 13C6-Q6 to that of wild type. It is important to note that at this stage, the wild-type cells showed a five-fold decrease in total Q6 content as compared to wild-type cells assayed during early log phase (compare Fig. S2 and S4). It is evident that Q6 content in wild-type yeast cells varies dramatically as a function of the growth phase and culture conditions. Thus, depending on the culture conditions, coq10 null mutant yeast can appear to have Q content that is not significantly different from wild-type cells (Fig. S4).

Although over-expression of Coq10p, CC1736, and Coq8p increased the amount of de novo 13C6-Q6, all coq10 null transformants continued to accumulate the early Q6-intermediates HAB and HHB (Fig. 9 and S3). This was also true for the late log phase cells (data not shown). Thus the presence of each of these multi-copy plasmids in the coq10 null mutant appears to impede the normal progression of Q biosynthetic steps, resulting in the accumulation of Q6-intermediates.

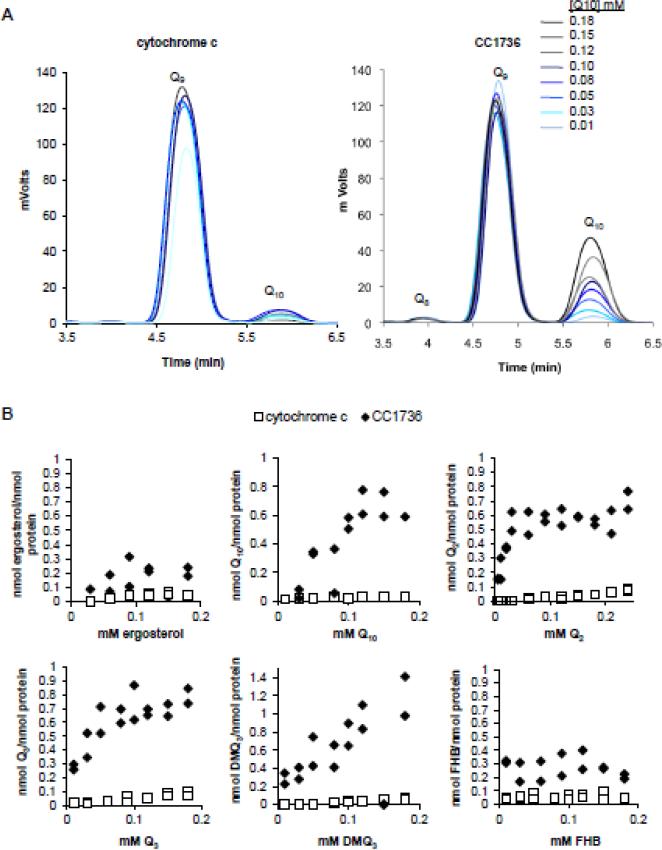

3.6 Q-binding by the purified CC1736 START domain polypeptide

Because S. cerevisiae Coq10p is prone to aggregation [10], we took advantage of the previously described purification of the C. crescentus CC1736 protein with carboxyl-terminal six-His tag (Section 2.12 and [32]). The molecular mass of the isolated CC1736 and K115E polypeptides and their tryptic peptide fragments were in agreement with the theoretical masses predicted from the respective amino acid sequences (Fig. S5). Despite many attempts, we were not able to over-express or purify the CC1736-V70K polypeptide.

We developed an in vitro binding assay (as described in Section 2.13) to determine whether purified CC1736-His8 polypeptide has Qn binding activity (Fig. 10). Because of the very low solubility of Q10, it was not possible to determine Bmax or Kd for this ligand (Table 4). However, CC1736 binding of Q3 and Q2 saturates at a molar ratio close to 1:1 (Table 4). CC1736 does not bind ergosterol (Fig. 10B), and an unrelated mitochondrial polypeptide (horse heart cytochrome c) lacks Q-binding, indicating specificity for Q in this binding assay. To examine whether CC1736 can bind intermediates of Q biosynthesis, DMQ3 and FHB were tested as ligands in the in vitro binding assay. The results indicate that CC1736 can bind DMQ3, a farnesylated analog of DMQ6, but is unable to bind to FHB, a farnesylated analog of an early intermediate of Q biosynthesis (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10.

C. crescentus CC1736 binds Q10, Q2, Q3, and DMQ3. (A) Purified CC1736 (right panel) or cytochrome c (left panel) were added to binding buffer containing Q10 at the eight concentrations designated (0.01-0.18 mM). Samples were incubated for 45 min at 30 °C and unbound ligands were separated from the protein by application to a desalting column, and lipid extracts of the eluate were subjected to reversed-phase HPLC and the ligands were detected by UV absorbtion as described in section 2.13. (B) shows the amount of each ligand recovered in association with either CC1736 (black diamonds) or cytochrome c (open squares): ergosterol, Q10, Q2, Q3, DMQ3, or FHB in ascending concentration. One representative assay is shown of at least two assays performed for each ligand. Each concentration of ligand was tested in duplicate per binding assay.

Table 4.

Determination of binding constants for CC1736

| CC1736 | Q2 | Q10 | Q3 | DMQ3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bmax | 1.11 ± 0.31 | 2.77 ± 2.90 | 1.56 ± 1.00 | 3.00 ± 0.82 |

| Kd (mM Ligand) | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.259 ± 0.356 | 0.035 ± 0.016 | 0.14 ± 0.077 |

Bmax, mol ligand bound : mol protein at saturation

Kd,, dissociation constant of ligand

Average ± standard deviation for two independent binding assays (see Fig. 10)

4. Discussion

Previous studies showed the yeast coq10 mutant to be Q6-replete, yet its respiratory defect was rescued by the addition of Q2, a soluble analog of Q6. This is a hallmark phenotype of the coq1-coq9 mutants that lack Q6 [10]. Thus, the role of Coq10p in facilitating the function of Q6 in respiratory electron transport poses an important and intriguing question. In this study we take advantage of the structurally characterized C. crescentus CC1736 START domain polypeptide [14]. We show that expression of CC1736 rescues the respiratory defects of the coq10 mutant, and hence functions as an ortholog of yeast Coq10p. Since human Coq10p also functions to restore respiration of the coq10 yeast mutant [10], Coq10p/CC1736 plays a conserved and essential role in facilitating the function of Q in respiration, from prokaryotes to eukaryotes.

C. crescentus CC1736 and the eukaryotic homologs of Coq10p belong to a family of lipid transfer proteins that contain a START domain. To date, Coq10p is the only identified START domain protein in S. cerevisiae [10, 43]. There are 15 identified members of the START domain protein family in mammals [44]. Members of the START domain superfamily function to transfer lipids between sub-cellular compartments, regulate lipid cell signaling events, and serve important roles in lipid metabolism [43]. Here we developed an in vitro binding assay and showed that CC1736 binds Q2 or Q10 in an equimolar ratio (Fig. 10). The absence of specificity for the length of the polyisoprenoid tail suggests that the binding site of CC1736 primarily recognizes the benzoquinone head group of Q. Our findings that CC1736 fails to bind either ergosterol or FHB, a farnesylated analog of an early Q-intermediate, are consistent with this idea. We also determined that CC1736 binds Q containing a farnesyl tail (Q3), and DMQ3, a farnesylated analog of demethoxy-Q, the penultimate Q-intermediate. Because CC1736 is amenable to NMR structural analyses [14], our results indicate that further study with CC1736 and Q analogs could identify the residues responsible for Q-binding.

Mutational analyses of yeast Coq10p have identified residues that are important for respiration and/or growth on non-fermentable sources [11, 18]. Here we showed that the V70K mutation in CC1736 prevented rescue of the coq10 null yeast (Fig. 2 and 3). However, the V70K mutation interfered with mitochondrial processing of the CC1736 polypeptide (Fig. S1). Therefore it is not certain whether the loss of function due to this mutation can be attributed to loss of binding or loss of correct targeting to mitochondria. Other studies testing functionality of Coq10 mutant polypeptides did not determine whether the mutant polypeptides were directed to mitochondria and correctly processed.

The yeast coq10 mutant is also rescued by over-expression of Coq8p. Over-expression of Coq8p in each of the coq null mutants (coq3-coq9) was recently shown to restore the steady-state levels of Coq4, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides [24, 25], and results in the accumulation of novel late-stage Q intermediates [25]. Conserved kinase sequence motifs present in Coq8 are essential for this stabilization [23, 25], consistent with the hypothesis that a phosphorylated, multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex is essential for Q biosynthesis [22, 23]. While these studies implicate Coq8 as a kinase responsible for mediating the phosphorylation of several of the Coq polypeptides, direct experimental evidence for Coq8 kinase activity is still lacking. The story is likely more complicated, since the phosphorylation state of two serine residues and one threonine residue identified in Coq7 appear to regulate Q biosynthesis [45]. Expression of Coq7 phosphomimetic forms decreased Q content, and while alanine substitution of these same residues increased Q content. The identity of the kinase(s) mediating such phosphorylation remains to be determined.

The multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex is likely to be important for the catalytic efficiency of Q biosynthesis, minimizing the release of Q-intermediates, including unsubstituted quinones, which are potentially reactive electrophiles, and catechols, which are prone to oxidation. In mitochondria isolated from the coq10 null mutant, steady state levels of Coq4p, Coq6p, Coq7p, and Coq9p are significantly decreased as shown by western blot analysis [20]. The imbalance of Coq proteins suggests that the Coq complex is unstable. Despite the disruption of the steady state levels of these Coq proteins, the coq10 null mutant continues to produce Q6 [10], and it was concluded that Coq10p was not essential for Q6 biosynthesis. However, previous studies did not address whether the yeast coq10 null mutants might have subtle impairments in de novo Q synthesis.

In this study we traced de novo Q6 synthesis with the 13C6-ring-labeled precursors 4HB and pABA. Our analyses show that the coq10 null mutant synthesizes Q6 less efficiently and accumulates high levels of the early Q-intermediates HHB and HAB as compared to wild-type yeast (Figs. 8-9 and S2-S3). The decreased de novo synthesis of Q6 is particularly obvious in early log phase cultures (Figs. 8 and S2). The inefficient Q biosynthesis observed in the coq10 mutant is rescued by the over-expression of Coq10p, Coq8p, and in part by C. crescentus CC1736 (Fig. 9 and S4). The decreased de novo synthesis of Q6 in the coq10 null is particularly obvious in early log phase cultures. This is primarily due to the higher content of Q6 in early log phase wild-type cells. In fact, wild-type yeast showed a profound decrease in Q6 biosynthesis and content during the progression from early- to late-log phase (Figs. 8 and S2). This decrease in Q6 content in wild-type cells accounts for an apparent near normal content of Q6 when coq10 null and wild-type cells harvested at late log (Fig. S4), or near stationary phase [10].

It seems likely that the decreased content and biosynthesis of Q6 in coq10 null cells during early log phase may account for their sensitivity to PUFA treatment (Figs. 4 - 7). PUFA sensitivity assays are routinely performed on early log-phase cultures, and over-expression of Coq10p, Coq8p, and CC1736 rescued the sensitivity of the coq10 mutant to PUFA treatment. Stress imposed by PUFA treatment is due to the presence of vulnerable bis-allylic hydrogen atoms [5, 34]. In the absence of chain-terminating antioxidants, such as QH2 or vitamin E, toxic PUFA autoxidation products accumulate and result in cell death. The sensitivity of the coq10 mutant to PUFA treatment is fully rescued by the addition of lipid soluble chain-terminating antioxidants, such as BHT or vitamin E. While addition of vitamin C fails to rescue the PUFA sensitivity of the Q-less coq mutants (such as coq3), vitamin C partially rescued the PUFA sensitivity of the coq10 mutant. These results indicate that in the absence of Coq10p, Q6 content in log phase cells may be inadequate. Hence the coq10 null cells are sensitive to PUFA stress, yet not as sensitive at the Q-less coq mutants. In the coq10 null mutant cells, vitamin C may act to restore this essential redox function of QH2.

Although over-expression of Coq8p, CC1736, or Coq10p in the coq10 null mutant results in a more efficient rate of de novo Q6 biosynthesis, high levels of the early Q6-intermediates HAB and HHB persist, suggesting that the stoichiometry of Coq8p and Coq10p is important for optimal Q6 synthesis. These results, together with our in vitro binding assays that show Q3 and DMQ3 bind to CC1736, suggest that Coq10:Q6 may stabilize the Coq polypeptide complex and/or enhance the efficiency of Q6 biosynthesis.

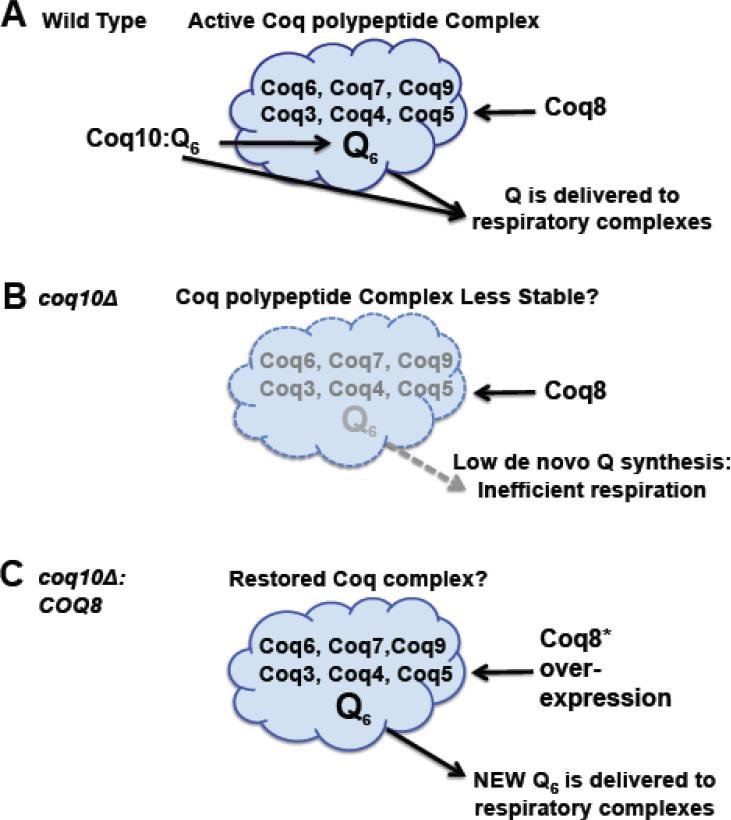

Future studies should aim to elucidate the relationship between Coq8p, Coq10p and the Coq polypeptide complex. We propose that Coq10p:Q6 may be important for the delivery of Q6 to the Coq polypeptide complex, generating de novo Q6, which is delivered to the respiratory complexes (Fig. 11A). The coq10 null mutant is known to contain lower steady state levels of the Coq4, Coq6, Coq7 and Coq9 polypeptides [20], decreased de novo Q6 biosynthesis (Figs. 8 and 9), and hence a less efficient delivery of “new Q” to the respiratory complexes (Fig. 11B). Over-expression of Coq8p restores de novo Q6 synthesis, and hence efficient delivery of Q6 to the respiratory complexes, even in the absence of Coq10p (Fig. 11C).

Figure 11.

A model for Coq10/START domain polypeptide function in de novo Q6 biosynthesis and in delivery of Q6 to respiratory chain complexes. (A) In wild-type cells, the Coq10:Q protein:ligand complex is postulated to deliver Q6 to the multisubunit Coq polypeptide complex and so enhance stability of the Coq polypeptides and de novo synthesis of Q6. Newly synthesized Q6 in the mitochondrial inner membrane is delivered to respiratory chain complexes and can function as an antioxidant. We postulate that Coq10:Q6 may also deliver Q6 to respiratory complexes. (B) The coq10 null mutant contains lower steady state levels of Coq polypeptides [20] and is shown with a less stable multisubunit Coq complex. Impaired de novo synthesis of Q6 and lack of Coq10:Q6 delivery to respiratory complexes accounts for the inefficient respiration observed in the coq10 null mutant. (C) The coq10 null mutant can be rescued by over-expression of COQ8, via its ability to restore the Coq polypeptide complex [25]. We postulate that the enhanced de novo Q6 biosynthesis formed by the Coq multisubunit complex is efficiently delivered to respiratory complexes, despite the absence of Coq10p.

The presence of Q6 or a Q6-intermediate is likely to be an essential component of the Coq polypeptide complex. Padilla et al., [26] showed that addition of Q6 to cultures of the coq7 null mutant re-establishes synthesis of DMQ6. In the absence of exogenous Q6 (or over-expression of Coq8p) the coq7 null mutant accumulates just the early intermediates HHB and HAB. We note that addition of exogenous Q6 may act directly to stabilize the Coq polypeptide multi-subunit complex [46], and via its interaction with Coq10p, may also be delivered to respiratory chain complexes. This model accounts for the observation that exogenously added Q6 failed to rescue a coq2/coq10 double mutant, but did rescue each of the single mutants, as well as the coq2/coq3 and coq2/coq4 double mutants [24].

The inefficiency in de novo Q6 biosynthesis reported here for the coq10 mutant does not result in a severe decrease in the total Q6 content. Thus, the severe respiratory defect and sensitivity to PUFA treatment manifested by the coq10 mutant remain to be explained. We propose that much of the Q6 pool in yeast may not be readily available for respiration, but may be sequestered or aggregated at some non-functional site. Addition of Q2 rescues the coq10 mutant because Q2 is a small soluble analog, less prone to aggregation/sequestration. We further propose that newly synthesized Q6 is accessible to the respiratory chain complexes, and can function as an antioxidant. A recent report indicates that the submitochondrial distribution of Q (inner versus outer membrane) impacts respiratory efficiency in mice harboring just one copy of the Coq7p ortholog Mclk1 [47]. It seems plausible that in turn, the content of Q in the inner membrane may be a direct function of Coq7p (and Coq10p:Q) in stabilizing the Coq multisubunit complex, and hence delivery of new Q to the respiratory complexes of the inner membrane. It is significant that restoration of small amounts of de novo Q synthesis affords profound rescue of Q-less yeast [23, 46] and C. elegans mutants [48, 49]. In this scenario, the provision of a small amount of newly synthesized Q may prime the assembly of Q into one or more sites of the respiratory chain complexes.

5. Conclusions

Expression of the CC1736 START domain polypeptide rescues the respiration defect and the PUFA sensitivity of the coq10 yeast mutant. In vitro binding assays show that CC1736 binds Q and the penultimate Q-biosynthetic intermediate DMQ. Although the yeast coq10 null mutant is replete in Q6, it is respiratory defective. In this study we use stable isotope ring precursors and show that de novo Q6 biosynthesis in the coq10 mutant is inefficient. Over-expression of Coq8p restores newly synthesized Q6 to wild-type levels, and rescues the respiratory deficiency and the sensitivity of the coq10 null mutant to PUFA stress. The results suggest that efficient Q de novo biosynthesis is important for the function of Q as a mobile electron carrier in the respiratory electron transport chain and as a chain-terminating antioxidant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Yeast coq10 mutants respire very poorly yet have a normal content of coenzyme Q6.

Expression of C. crescentus CC1736 START domain protein rescues the coq10 mutant.

CC1736 binds Q3 or demethoxy-Q3, but doesn't bind 3-farnesyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid.

coq-10 mutants show decreased de novo Q synthesis and accumulate Q-intermediates.

Coq10p facilitates Q biosynthesis and may deliver new Q to respiratory complexes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Grant 0919609 (to CFC) and by the National Institutes of Health (R01RR020004, now reassigned as R01GM103479, to JAL; S10RR024605 from the National Center for Research Resources for purchase of the LC-MS/MS system). We thank Alexander Tzagoloff for sending us the yeast coq10 mutant, Gaetano Montelione, Thomas Szyperski, and Greg Kornhaber for the pCcrR19-21.1 plasmid and for advice on purification of CC1736, Letian Xie and Beth Marbois for advice and help with lipid extractions and HPLC/MS-MS, Steve Karpowicz for help with sequence alignment, Bradley Kay for assistance with the fatty acid sensitivity assays, Yavus Oktay for help with oxygen consumption measurements, and Steve Clarke and members of the CF Clarke lab for advice and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: αLnn, α-linolenic acid (C18:3, n–3); BCA, bicinchoninic acid; BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; BN-PAGE, blue native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; DMQ, demethoxy-Q; DOD, drop out growth medium with dextrose; FHB, farnesyl-hydroxybenzoate; HAB, hexaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid; HHB, hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; IDMQ, 4-imino-demethoxy-Q; pABA, para–aminobenzoic acid; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; Q, coenzyme Q or ubiquinone; QH2, coenzyme QH2 or ubiquinol; START, steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer; YPD, rich growth medium with dextrose; YPG, rich growth medium with glycerol; YPGal, rich growth medium with galactose.

References

- 1.Hatefi Y. The mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:1015–1069. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crane FL. Distribution of ubiquinones. In: Morton RA, editor. Biochemistry of quinones. Academic Press; London: 1965. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Do TQ, Schultz JR, Clarke CF. Enhanced sensitivity of ubiquinone deficient mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to products of autooxidized polyunsaturated fatty acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill S, Hirano K, Shmanai VV, Marbois BN, Vidovic D, Bekish AV, Kay B, Tse V, Fine J, Clarke CF, Shchepinov MS. Isotope-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids protect yeast cells from oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzagoloff A, Dieckmann CL. PET genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1990;54:211–225. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.211-225.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierrel F, Hamelin O, Douki T, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Muhlenhoff U, Ozeir M, Lill R, Fontecave M. Involvement of mitochondrial ferredoxin and para-aminobenzoic acid in yeast coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2010;17:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran UC, Clarke CF. Endogenous synthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Mitochondrion. 2007;7S:S62–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozeir M, Muhlenhoff U, Webert H, Lill R, Fontecave M, Pierrel F. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis: Coq6 is required for the C5-hydroxylation reaction and substrate analogs rescue Coq6 deficiency. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1134–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barros MH, Johnson A, Gin P, Marbois BN, Clarke CF, Tzagoloff A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae COQ10 gene encodes a START domain protein required for function of coenzyme Q in respiration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42627–42635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui TZ, Kawamukai M. Coq10, a mitochondrial coenzyme Q binding protein, is required for proper respiration in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Febs J. 2009;276:748–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busso C, Tahara EB, Ogusucu R, Augusto O, Ferreira-Junior JR, Tzagoloff A, Kowaltowski AJ, Barros MH. Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq10 null mutants are responsive to antimycin A. Febs J. 2010;277:4530–4538. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Y, Goldsmith-Fischman S, Atreya HS, Acton T, Ma L, Xiao R, Honig B, Montelione GT, Szyperski T. NMR structure of the 18 kDa protein CC1736 from Caulobacter crescentus identifies a member of the START domain superfamily and suggests residues mediating substrate specificity. Proteins. 2005;58:747–750. doi: 10.1002/prot.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponting CP, Aravind L. START: a lipid-binding domain in StAR, HD-ZIP and signalling proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:130–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WL. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a novel mitochondrial cholesterol transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo Conte L, Ailey B, Hubbard TJ, Brenner SE, Murzin AG, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:257–259. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busso C, Bleicher L, Ferreira-Junior JR, Barros MH. Site-directed mutagenesis and structural modeling of Coq10p indicate the presence of a tunnel for coenzyme Q6 binding. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1609–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marbois B, Gin P, Faull KF, Poon WW, Lee PT, Strahan J, Shepherd JN, Clarke CF. Coq3 and Coq4 define a polypeptide complex in yeast mitochondria for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20231–20238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh EJ, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Tran UC, Saiki R, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Coq9 polypeptide is a subunit of the mitochondrial coenzyme Q biosynthetic complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;463:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Clarke CF. The yeast Coq4 polypeptide organizes a mitochondrial protein complex essential for coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauche A, Krause-Buchholz U, Rodel G. Ubiquinone biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the molecular organization of O-methylase Coq3p depends on Abc1p/Coq8p. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:1263–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie LX, Hsieh EJ, Watanabe S, Allan CM, Chen JY, Tran UC, Clarke CF. Expression of the human atypical kinase ADCK3 rescues coenzyme Q biosynthesis and phosphorylation of Coq polypeptides in yeast coq8 mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zampol MA, Busso C, Gomes F, Ferreira-Junior JR, Tzagoloff A, Barros MH. Over-expression of COQ10 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibits mitochondrial respiration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie LX, Ozeir M, Tang JY, Chen JY, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Fontecave M, Clarke CF, Pierrel F. Over-expression of the Coq8 kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq null mutants allows for accumulation of diagnostic intermediates of the Coenzyme Q6 biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padilla S, Tran UC, Jimenez-Hidalgo M, Lopez-Martin JM, Martin- Montalvo A, Clarke CF, Navas P, Santos-Ocana C. Hydroxylation of demethoxy-Q6 constitutes a control point in yeast coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:173–186. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barkovich RJ, Shtanko A, Shepherd JA, Lee PT, Myles DC, Tzagoloff A, Clarke CF. Characterization of the COQ5 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Evidence for a C-methyltransferase in ubiquinone biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9182–9188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marbois B, Xie LX, Choi S, Hirano K, Hyman K, Clarke CF. para-Aminobenzoic acid is a precursor in coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27827–27838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu AY, Poon WW, Shepherd JA, Myles DC, Clarke CF. Complementation of coq3 mutant yeast by mitochondrial targeting of the Escherichia coli UbiG polypeptide: evidence that UbiG catalyzes both O-methylation steps in ubiquinone biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9797–9806. doi: 10.1021/bi9602932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Y, Atreya HS, Xiao R, Acton TB, Shastry R, Ma L, Montelione GT, Szyperski T. Resonance assignments for the 18 kDa protein CC1736 from Caulobacter crescentus. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:549–550. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000034356.06183.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elble R. A simple and efficient procedure for transformation of yeasts. Biotechniques. 1992;13:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill S, Lamberson CR, Xu L, To R, Tsui HS, Shmanai VV, Bekish AV, Awad AM, Marbois BN, Cantor CR, Porter NA, Clarke CF, Shchepinov MS. Small amounts of isotope-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress lipid autoxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glick BS, Pon LA. Isolation of highly purified mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaire C, Dujardin G. Preparation of respiratory chain complexes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae wild-type and mutant mitochondria : activity measurement and subunit composition analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;432:65–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-028-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poon WW, Barkovich RJ, Hsu AY, Frankel A, Lee PT, Shepherd JN, Myles DC, Clarke CF. Yeast and rat Coq3 and Escherichia coli UbiG polypeptides catalyze both O-methyltransferase steps in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21665–21672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shepherd JA, Poon WW, Myles DC, Clarke CF. The biosynthesis of ubiquinone: Synthesis and enzymatic modification of biosynthetic precursors. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:2395–2398. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saiki R, Lunceford AL, Shi Y, Marbois B, King R, Pachuski J, Kawamukai M, Gasser DL, Clarke CF. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation rescues renal disease in Pdss2kd/kd mice with mutations in prenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1535–1544. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90445.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Sensitivity to treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids is a general characteristic of the ubiquinone-deficient yeast coq mutants. Molec. Aspects Med. 1997;18:s121–s127. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]