Abstract

Prior research indicates that infants with absent fathers are vulnerable to unfavorable fetal birth outcomes. HIV is a recognized risk factor for adverse birth outcomes. However, the influence of paternal involvement on fetal morbidity outcomes in women with HIV remains poorly understood. Using linked hospital discharge data and vital statistics records for the state of Florida (1998–2007), the authors assessed the association between paternal involvement and fetal growth outcomes (i.e., low birth weight [LBW], very low birth weight [VLBW], preterm birth [PTB], very preterm birth [VPTB], and small for gestational age [SGA]) among HIV-positive mothers (N = 4,719). Propensity score matching was used to match cases (absent fathers) to controls (fathers involved). Conditional logistic regression was employed to generate adjusted odds ratios (OR). Mothers of infants with absent fathers were more likely to be Black, younger (<35 years old), and unmarried with at least a high school education (p < .01). They were also more likely to have a history of drug (p < .01) and alcohol (p = .02) abuse. These differences disappeared after propensity score matching. Infants of HIV-positive mothers with absent paternal involvement during pregnancy had elevated risks for adverse fetal outcomes (LBW: OR = 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.05–1.60; VLBW: OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.05–2.82; PTB: OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.13–1.69; VPTB: OR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.13–2.90). Absence of fathers increases the likelihood of adverse fetal morbidity outcomes in women with HIV infection. These findings underscore the importance of paternal involvement during pregnancy, especially as an important component of programs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Introduction

While the overall HIV/AIDS epidemic in the US and Florida has experienced significant decline, the prevalence and incidence rates of HIV/AIDS among women have escalated, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities. From 1987 to 2010, the proportion of all AIDS cases among women in Florida rose from 11% to 32% (Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDS., 2010b). Minority women in Florida have significantly higher AIDS case rates compared to white women (Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDS., 2008). Among pregnant women, a recent trend analysis found that HIV/AIDS rates decreased by about 15% between 1998 and 2007 (Salihu et al., 2010). Similarly, a racial/ethnic disparity was observed, with Black and Latino mothers experiencing HIV/AIDS rates 11 times and two times higher than white mothers, respectively (Salihu, et al., 2010).

Perinatal transmission of HIV in Florida has decreased by 94% from 1993 to 2009 (Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDs., 2010a). Much of this improvement is attributed to national guidelines that were established regarding the provision of antiretroviral treatment of HIV-positive mothers (Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDs., 2010a). Additionally, in 1996, the Florida legislature mandated the offering of HIV testing to pregnant women (Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDs., 2010a; Florida Senate; Committee on Health Policy., 2007). In 2005, this law was amended to add HIV testing to routine prenatal care with an opt-out option, which allowed women to decline testing (Florida Senate; Committee on Health Policy., 2007).

Prior research has documented the association between maternal HIV status and an increased likelihood of multiple adverse birth outcomes, including low birth weight (LBW) (Bodkin, Klopper, & Langley, 2006; Ickovics et al., 2000; Lambert et al., 2000; Leroy et al., 1998), preterm birth (PTB) (Lambert, et al., 2000; Marazzi et al., 2011), small for gestational age (SGA) (Ndirangu, Newell, Bland, & Thorne, 2012) and intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) (Bodkin, et al., 2006). Studies have also investigated the role of antiretroviral therapy on fetal growth outcomes among women treated for HIV during pregnancy; however, there has been no clear consensus on their effect of fetal growth (Briand et al., 2009; Haeri et al., 2009; Hernandez et al., 2012; Rudin et al., 2011) A specific group of antiretrovirals (non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, e.g. efavirenz) are known to be potentially teratogenic (Hernandez, et al., 2012; Knapp et al., 2012).

The scientific literature is replete with studies of the impact of paternal involvement on feto-infant morbidities. Ngui and colleagues found that infants born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin with no father recorded on the birth certificate and those whose paternity was court-determined faced the highest risk of PTB and LBW across all racial/ethnic groups (Ngui, Cortright, & Blair, 2009). Similarly, researchers have previously reported an association between lack of father identification on birth certificates and heightened PTB and LBW in Florida (Alio, Kornosky, Mbah, Marty, & Salihu, 2010). Additionally, a study conducted in Georgia reported a higher risk for infant death when the father was not named on the birth certificate (Gaudino, Jenkins, & Rochat, 1999). This elevated risk persisted after adjustment for confounders generally predictive of infant mortality, including low birth weight, adequacy of prenatal care, congenital anomalies, tobacco use, maternal and age, gestational age, and pregnancy complications (Gaudino, et al., 1999).

Ickovics and colleagues found that in women with or at high risk for HIV and those who did not live with their partners were more than twice as likely to have infants with LBW (Ickovics, et al., 2000). A racial disparity was observed, with blacks having higher LBW rates compared to whites (Ickovics, et al., 2000). Despite the potential relationship between paternal involvement and maternal HIV status and their joint impact on birth outcomes, few studies have investigated the confluence of these factors. We therefore, conducted the current study to address these issues based on the following hypotheses:

HIV-positive women with absent fathers during pregnancy are at elevated risk for adverse birth outcomes.

Given the known racial disparity in both HIV prevalence and adverse birth outcomes, we further hypothesize that the relationship between absent fathers and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-positive mothers will be more pronounced among blacks.

Methods

We performed a population-based retrospective cohort analysis utilizing the Florida hospital discharge data linked to vital records for the years 1998 through 2007. The Hospital Inpatient Discharge (HID) data were obtained from the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA), while the vital records were acquired from the Florida Department of Health (FDOH). The linked dataset contains only singleton live births, as listed on both the hospital discharge data and the vital records. The linkage of the two data sources resulted in a 97.6% success rate, which has been internally validated and submitted for publication elsewhere (blinded for review). The data linkage process utilized the hospital discharge record as the master files that formed the initial template for linkage with the vital records. The procedure involved a stepwise deterministic approach that identified and linked maternal-infant dyad records in a longitudinal fashion from birth to one year post-delivery or until infant death.

In this analysis, we only included mothers who were HIV-positive, as determined by the HID data. Deliveries with no birth weight record and births at less than 20 weeks or greater than 44 weeks of gestation were excluded. Subjects with missing values in one or more of the socio-demographic variables or selected pregnancy complications were also omitted from the final analyses. After applying exclusion criteria for the study, the study population totaled 4,719. The population was divided into two groups based on paternal involvement, as indicated by the identification of a father in the vital records data. The exposed group, denoting paternal involvement, consisted of 3,167 records, while the unexposed comparison group was comprised of 1,552 records.

HID data provided diagnoses for maternal HIV status and pregnancy complications, identified using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition (ICD-9). These codes were used to identify all cases of: HIV/AIDS (ICD-9 codes: V08, 042-044, 079.53); anemia (ICD-9 codes: 280, 281, 282, 283, 284, 285, 648.2); gestational diabetes (ICD-9 codes: 648.8); diabetes mellitus (ICD-9 codes: 250, 648.0); pregnancy induced hypertension (ICD-9 codes: 642.3, 642.7, 642.9); hypertension complicating pregnancy (ICD-9 codes: 642); pre-existing hypertension (ICD-9 codes: 401, 642.0, 6421, 642.2, 642.7); preeclampsia (ICD-9 codes: 642.4, 642.5); eclampsia (ICD-9 codes: 642.6); placenta abruption (ICD-9 codes: 641.2, 762.1); placenta accreta (ICD-9 codes: 666.0, 667.0); and placenta previa (ICD-9 codes: 641.0, 641.1, 762.0). Alcohol abuse was also determined using the following ICD-9 codes: acute alcohol intoxication (303.00–03); alcohol dependence (303.90–93); nondependent alcohol abuse, such as “binge drinking” (305.00–03); alcohol-induced mental disorders (291.0–5, 9; 291.81–82, 89); and alcohol affecting the fetus or newborn via placenta or breast milk (760.71). ICD-9 codes signifying drug dependence complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium or post-delivery period (648.30–648.34) were utilized to determine drug abuse.

The vital records data provided socio-demographic information and infant characteristics (i.e., gestational age, birth weight, infant gender). Race/ethnicity was categorized into four groups: non-Hispanic black (black), non-Hispanic white (white), and Hispanic, and other. Education was classified as those with at least a high school degree (≥12 years) and those without a high school degree (<12 years); individuals with missing information regarding educational status were grouped in the latter category (<12 years). Age was dichotomized into <35 years and ≥35 years. Maternal marital status was grouped as either married or unmarried, with all persons divorced, widowed, or of unknown marital status classified as unmarried. Parity was grouped as either nulliparous or parous. Adequacy of prenatal care was assessed using the Revised-Graduated Index of prenatal care utilization (R-GINDEX), which assesses the adequacy of care on the basis of the trimester that prenatal care began, the number of visits and the gestational age of infant at birth (Alexander & Kotelchuck, 1996). In this study, inadequate prenatal care utilization refers to women who either had missing prenatal care information, had prenatal care but the level was considered sub-optimal, or mothers who had no prenatal care at all. Smoking status among mothers was determined using the variable in the vital records.

The main outcomes of interest in this study were feto-infant morbidity outcomes, including low birth weight (LBW), very low birth weight (VLBW), preterm birth (PTB), very preterm birth (VPTB), and small for gestational age (SGA). LBW was defined as infants weighing below 2500 grams at birth; VLBW infants weighed below 1500 grams at birth; PTB was defined as any birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation; VPTB were births before 32 completed weeks of gestation; and SGA was defined as infants weighing below the 10th percentile of birth weight for their gestational age using normalized growth curves (Alexander, Kogan, Martin, & Papiernik, 1998). Gestational age was primarily based on the interval between the last menstrual period and the date of delivery of the baby (95% of cases). When the menstrual estimate of gestational age was inconsistent with the birth weight (e.g., very low birth weight at term), a clinical estimate of gestational age on the vital records was used instead (Taffel, Johnson, & Heuser, 1982).

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare crude frequencies with respect to socio-demographic characteristics and pregnancy complications between the exposed and unexposed groups. Because the baseline demographics and pregnancy-related clinical conditions of women who experienced pregnancies with paternal involvement (exposed) differed from those without paternal involvement (unexposed), we used a 1:1 propensity score matching approach to adjust for these differences. The propensity score matching technique balances the observed covariates that might potentially impact the consequence of exposure by weighting subjects in either group with a single composite measure computed from all measured covariates (Austin, 2008). Socio-demographic variables and pregnancy-related clinical conditions before and after propensity score matching are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Crude frequencies of selected maternal socio-demographic characteristics among HIV-positive mothers categorized by father involvement status before and after propensity score matching (1998–2007).

| Socio-demographic Characteristics and pregnancy conditions | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Father involved n=3,146 | Father not involved n=1,531 | p-value | Father involved n=1,487 | Father not involved n=1,487 | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Advanced age (≥ 35 years old) | 13.64 | 8.88 | <0.01 | 8.47 | 8.94 | 0.65 |

|

| ||||||

| Education (≥ 12 years) | 34.62 | 47.35 | <0.01 | 46.60 | 46.54 | 0.97 |

|

| ||||||

| Smokers | 11.16 | 15.81 | <0.01 | 15.60 | 14.32 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||||

| Adequate prenatal care (yes) | 40.34 | 29.92 | <0.01 | 30.60 | 30.33 | 0.87 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 13.99 | 9.93 | <0.01 | 11.03 | 9.82 | 0.56 |

| Black | 71.17 | 81.58 | 81.24 | 81.51 | ||

| Hispanic | 12.21 | 6.73 | 5.99 | 6.93 | ||

| Other | 2.64 | 1.76 | 1.75 | 1.75 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Not married | 67.48 | 94.25 | <0.01 | 94.08 | 94.08 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Nulliparous | 19.68 | 22.01 | 0.07 | 20.85 | 21.79 | 0.82 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.25 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.40 |

|

| ||||||

| Drug abuse | 2.83 | 7.38 | <0.01 | 4.37 | 5.11 | 0.34 |

Table 2.

Crude frequencies of selected pregnancy-related complications among HIV-positive mothers categorized by father involvement status before and after propensity score matching (1998–2007).

| Socio-demographic Characteristics and pregnancy conditions | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father involved n=3,146 | Father not involved n=1,531 | p-value | Father involved n=1,487 | Father not involved n=1,487 | P-value | |

| Anemia | 13.35 | 15.81 | 0.02 | 14.19 | 15.94 | 0.18 |

| Gestational diabetes | 2.54 | 1.24 | <0.01 | 0.67 | 1.21 | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| pregnancy-induced hypertension | 2.00 | 1.44 | 0.17 | 1.08 | 1.48 | 0.33 |

| Hypertension complicating pregnancy | 10.04 | 9.21 | 0.37 | 7.94 | 8.94 | 0.32 |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 2.83 | 3.53 | 0.19 | 3.30 | 3.43 | 0.84 |

| Preeclampsia | 3.59 | 3.14 | 0.42 | 2.35 | 2.89 | 0.36 |

| Abruption | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.44 |

| Placenta previa | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.76 |

| Drug abuse | 2.83 | 7.38 | <0.01 | 4.37 | 5.11 | 0.34 |

To address bias that could result from the non-independent nature of the matched data, we used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) method to compute adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for our outcomes.(Austin, 2008) After propensity score matching, AORs were derived by loading all the variables that were considered to be potential confounders into the model (i.e., maternal age, parity, race, smoking, education, marital status, adequacy of prenatal care, anemia, gestational diabetes, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, hypertension complicating pregnancy childbirth and the puerperium, pre-existing hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, placenta accreta, previa, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse). All tests were two tailed with a type 1 error rate fixed at 5%. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, version 9.2). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of South Florida.

Results

The crude rates of maternal socio-demographic factors among HIV-positive mothers in Florida are presented in Table 1. Before propensity score matching, HIV-positive women who gave birth with an absent father were more likely to be younger, black, unmarried, to smoke cigarettes, use illicit drugs/alcohol, and to have adequate prenatal care and at least a high school education compared to those who identified a birth father. After propensity score 1matching, these demographic differences between exposed and unexposed groups were attenuated.

A comparison of selected pregnancy complications within the study population is presented in Table 2. Before propensity score matching, complications were generally similar among HIV-positive mothers, regardless of paternal involvement. Mothers with absent fathers/partners were more than 2.5 times as likely to abuse alcohol and drugs. Additionally, mothers with an absent father/partner were 20% more likely to have anemia, while those with involved fathers/partners were more than twice as likely to have gestational diabetes. Following propensity score matching, differences in pregnancy-related complications between the two groups became less evident.

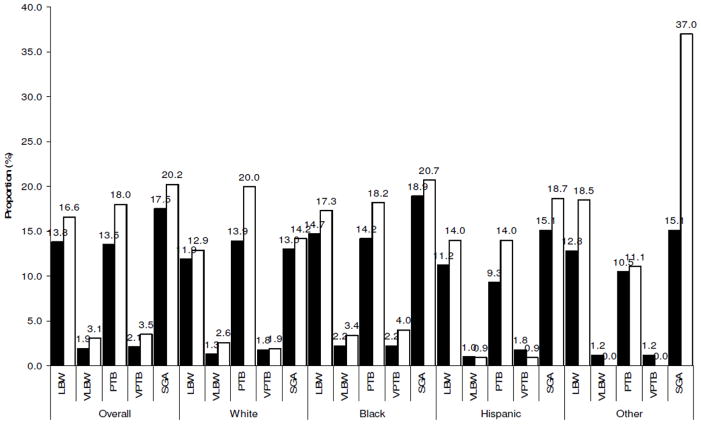

The incidence of adverse feto-infant morbidity outcomes associated with absent fathers is shown in Figure 1, while the estimated risks are presented in Table 3. Overall, HIV-positive mothers with absent fathers had higher odds of experiencing adverse birth outcomes, with higher estimates noted for the more severe outcomes. HIV-positive mothers with uninvolved fathers were 87% more likely to have a VLBW infant (AOR=1.87, 95%CI: 1.14–3.05)), 47% more likely to have a preterm birth (AOR=1.47, 95%CI: 1.20–1.80), and 80% more likely to have a very preterm delivery (AOR=1.80, 95%CI: 1.13–2.84) than their counterparts with involved fathers. There were no differences between groups in the occurrence of low birth weight and small for gestational age (SGA). The difference in risk of very low birth weight, preterm and very preterm birth between the two groups was replicated among Black women, but not among women of White or Hispanic race/ethnicity (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Incidence of feto-infant morbidity outcomes associated with absent fathers among HIV-positive pregnant women overall and categorized by race (empty bars refer to the group with absent fathers)

Table 3.

Odds ratios for the association between feto-infant morbidity outcomes and paternal non-involvement among offspring of HIV-positive mothers in Florida, after propensity score matching (1998–2007)a*

| Morbidity outcomes | Father involved n=1,487 | Father not involved n=1,487 |

|---|---|---|

| LBW (n=447) | 1.0 | 1.22 (0.99–1.49) |

| VLBW (n=71) | 1.0 | 1.87 (1.14–3.05) |

| PTB (n=451) | 1.0 | 1.47 (1.20–1.80) |

| VPTB (n=83) | 1.0 | 1.80 (1.13–2.84) |

| SGA (n=579) | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.87–1.24) |

Abbreviations: AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95% CI=95% Confidence Intervals; LBW=low birth weight; VLBW= very low birth weight; PTB= preterm birth; VPTB= very preterm birth; SGA=small for gestational age

Significant findings are in bold font.

Estimates were matched by the following maternal characteristics and pregnancy-related complications: maternal age, parity, race, smoking, education, marital status, adequacy of prenatal care, anemia, gestational diabetes, placenta accreta, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, hypertension complicating pregnancy, pre-existing hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, placenta previa, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse.

Table 4.

Odds ratio for the association between feto-infant morbidity outcomes and paternal non-involvement among offspring of HIV-positive mothers in Florida categorized by race, after propensity score matching (1998–2007)a*

| White | Black | Hispanic | Other | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Father involved n=184 | Father absent n=144 | n | Father involved n=1,119 | Father absent n=1,214 | n | Father involved n=143 | Father absent n=101 | n | Father involved n=38 | Father absent n=25 | |

| LBW | 36 | 1.0 | 1.16 (0.58–2.35) | 373 | 1.0 | 1.15 (0.92–1.44) | 24 | 1.0 | 1.47 (0.63–3.45) | 9 | 1.0 | 2.12 (0.51–8.85) |

| VLBW | 6 | 1.0 | 2.60 (0.47–14.5) | 63 | 1.0 | 1.74 (1.03–2.94) | 3 | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.06–7.87) | 1 | 1.0 | - |

| PTB | 50 | 1.0 | 1.62 (0.87–2.99) | 372 | 1.0 | 1.37 (1.09–1.72) | 19 | 1.0 | 2.62 (0.99–6.93) | 8 | 1.0 | 0.90 (0.19–4.15) |

| VPTB | 6 | 1.0 | 1.28 (0.25–6.47) | 73 | 1.0 | 1.80 (1.11–2.92) | 3 | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.06–7.87) | 1 | 1.0 | - |

| SGA | 42 | 1.0 | 1.06 (0.55–2.07) | 475 | 1.0 | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | 42 | 1.0 | 1.21 (0.62–2.34) | 14 | 1.0 | 3.71 (1.07–12.9) |

Abbreviations: AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95% CI=95% Confidence Intervals; LBW=low birth weight; VLBW= very low birth weight; PTB= preterm birth; VPTB=very preterm birth; SGA=small for gestational age

Significant findings are in bold font.

Estimates were matched by the following maternal characteristics and pregnancy-related complications: maternal age, parity, smoking, education, marital status, adequacy of prenatal care, anemia, gestational diabetes, placenta accreta, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, hypertension complicating pregnancy, pre-existing hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, placenta previa, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse

Discussion

The findings in this study suggest that a lack of paternal involvement was associated with increased risk of adverse birth outcomes in HIV-positive mothers, specifically very low birth weight, preterm delivery and very preterm delivery. Our findings are not surprising. It is widely recognized that fathers play an important role in pregnancy and childbirth, providing psychological and material support to the mother during the prenatal period and beyond. There is a consistent association between paternal involvement and positive health-seeking behaviors in pregnancy, such as accessing prenatal care in the first trimester and reduced tobacco and alcohol consumption (Martin, McNamara, Milot, Halle, & Hair, 2007; Teitler, 2001). HIV studies also document an association between paternal involvement in pregnancy and optimum outcomes related to infant feeding, clinic utilization and increased adherence to treatment services (Cames et al., 2010; Montgomery et al., 2011).

Male partner involvement is a priority area for programs for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT). Male participation in antenatal care with couple counseling and testing for HIV increases PMTCT uptake and adherence (Farquhar et al., 2004; Painter, 2001; Semrau et al., 2005), facilitates communication about HIV status between couples, strengthens adoption of safe sexual behavior (Mbonye, Hansen, Wamono, & Magnussen, 2010), and reduces HIV-1 transmission in serodiscordant relationships (Allen et al., 2003; Allen et al., 1992; Bunnell et al., 2005). Our findings provide evidence of additional advantages conferred by paternal involvement during pregnancy beyond the documented benefits on HIV transmission outcomes.

After subgroup analysis we found that lack of paternal involvement remained a significant predictor of adverse fetal growth outcomes in black mothers, but not in White and Hispanic women. We have previously shown in a non-HIV study population that the impact of paternal non-involvement on fetal morbidity is more pronounced among Black women than White or Hispanic mothers (Alio, et al., 2010). However, because the overwhelming majority of the study population in this study (81%) comprised Black women, we believe that the difference in outcomes by race/ethnicity we report here are more likely an indication of inadequate power/small sample size among Whites/Hispanics than a true disparity in outcomes by race/ethnicity. A mechanism by which paternal involvement may improve birth outcomes is via reduction of stress and provision of social support. Preterm delivery is consistently associated with maternal stress (Copper et al., 1996; Giscombe & Lobel, 2005; Hobel, Goldstein, & Barrett, 2008; Sable & Wilkinson, 2000). Stress may instigate preterm birth and associated low birth weight through activation of the neuroendocrine system, stimulation of the inflammatory response, and increased susceptibility to infection.(Wadhwa et al., 2001). In addition to its direct biological effect, stress can also encourage poor coping behaviors, such as substance abuse and poor diet (Kramer et al., 2001), which are risk factors for preterm birth and low birth weight. Paternal involvement may reduce the prevalence of these risk factors. A recent case-control study provides evidence that paternal support may moderate the effects of chronic stress on the risk of preterm delivery (Ghosh, Wilhelm, Dunkel-Schetter, Lombardi & Ritz, 2010).

Some studies have documented a positive influence on birth outcomes due to social support from peers, other community members, and intimate partners, although the results are not conclusive (Elsenbruch et al., 2007; Ghosh, Wilhelm, Dunkel-Schetter, Lombardi, & Ritz, 2010). As fathers have greater involvement with their pregnant partners, they may have more opportunities to provide social support that can ameliorate the effects of stress during pregnancy. These potentially beneficial effects of paternal involvement are particularly important for women living with HIV/AIDS, who face the physiological and psychological stressors associated with living with a chronic infectious disease.

A major strength of this study is the population-based design, which increases the generalizability of our findings. In addition, our use of appropriate analytic approaches (propensity score matching and generalized estimating equations) reduces the likelihood of bias associated with potential confounding and non-independence in our data, thereby improving the validity of our report. This study is not without limitations. An important drawback is our measurement of the construct of paternal involvement. Lack of father’s name on the birth certificate indicates absence of the father (Gaudino, et al., 1999), however, there are many gradations of the parental relationship that are not captured by the dichotomous variable of father listed on the birth certificate. These nuances of the extent to which fathers are involved are not captured in vital statistics data. In addition, socio-contextual factors that could explain the lack of documentation of the father’s name on the birth certificate, e.g., financial considerations, partner conflict, custody issues, incarcerated partner, etc., are not captured by our data. We are therefore unable to comment on how these levels of paternal involvement and underlying social correlates impact our study findings. On the other hand, associations observed would likely have been stronger had all fathers whose name was on the birth certificate been actively involved in pregnancy. The study also does not allow us to draw firm conclusions regarding causality, as the absence of father’s name on the birth certificate could merely be correlated to adverse birth outcomes, and correlation does not necessarily imply causation.

In summary, we report an association between lack of paternal involvement and the risk of very low birth weight and preterm and very preterm delivery in a large cohort of HIV-positive mothers in Florida. Our findings add to the evidence basis of the benefits associated with paternal involvement in pregnancy, and suggest a need greater focus on the role of fathers in policies and programs targeting pregnant women and women of childbearing age living with HIV/AIDS. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which paternal involvement mediates the risk factors for low birth weight and preterm delivery in HIV-positive pregnant women. An understanding of these factors will lead to the development of interventions to promote optimal fetal development among infants of HIV-positive mothers.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by a grant from the Health Resource Service Administration (HRSA), Maternal Child Health Bureau (Grant # H49MC12793). Dr. Aliyu is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD075075. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alexander GR, Kogan M, Martin J, Papiernik E. What are the fetal growth patterns of singletons, twins, and triplets in the United States? Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;41(1):114–125. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199803000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(5):408–418. discussion 419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alio AP, Kornosky JL, Mbah AK, Marty PJ, Salihu HM. The Impact of Paternal Involvement on Feto-Infant Morbidity Among Whites, Blacks and Hispanics. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;14(5):735–741. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, Zulu I, Trask S, Fideli U, Haworth A. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050867.71999.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, Hulley S. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. BMJ. 1992;304(6842):1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC. A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med. 2008;27(12):2037–2049. doi: 10.1002/sim.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin C, Klopper H, Langley G. A comparison of HIV positive and negative pregnant women at a public sector hospital in South Africa. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15(6):735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand N, Mandelbrot L, Le Chenadec J, Tubiana R, Teglas JP, Faye A, Cohort AFP. No relation between in-utero exposure to HAART and intrauterine growth retardation. AIDS. 2009;23(10):1235–1243. doi: 10.1097/Qad.0b013e32832be0df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell RE, Nassozi J, Marum E, Mubangizi J, Malamba S, Dillon B, Mermin JH. Living with discordance: knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):999–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cames C, Saher A, Ayassou KA, Cournil A, Meda N, Simondon KB. Acceptability and feasibility of infant-feeding options: experiences of HIV-infected mothers in the World Health Organization Kesho Bora mother-to-child transmission prevention (PMTCT) trial in Burkina Faso. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6(3):253–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, Dombrowski MP. The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175(5):1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Benson S, Rucke M, Rose M, Dudenhausen J, Pincus-Knackstedt MK, Arck PC. Social support during pregnancy: effects on maternal depressive symptoms, smoking and pregnancy outcome. Human Reproduction. 2007;22(3):869–877. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Kabura MN, John FN, Nduati RW, John-Stewart GC. Antenatal couple counseling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(5):1620–1626. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDS. Organizing to Survive: The HIV/AIDS Crisis Among Florida’s Women. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDS. Florida Annual Report 2009: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome/Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Health; 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health; Bureau of HIV/AIDS. HIV among Women, 2010. 2010b Retrieved August 8, 2012, from http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/aids/updates/facts/10Facts/2010_Women_Fact_sheet.pdf.

- Florida Senate; Committee on Health Policy. The Florida Senate: Interim project report 2008–134: Review of the Florida Statutes Relating to HIV Testing. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Senate; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudino JA, Jenkins B, Rochat RW. No fathers’ names: a risk factor for infant mortality in the State of Georgia, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48(2):253–265. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh JKC, Wilhelm MH, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lombardi CA, Ritz BR. Paternal support and preterm birth, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a study in Los Angeles County mothers. Archives of Womens Mental Health. 2010;13(4):327–338. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0135-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giscombe CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(5):662–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeri S, Shauer M, Dale M, Leslie J, Baker AM, Saddlemire S, Boggess K. Obstetric and newborn infant outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women who receive highly active antiretroviral therapy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;201(3) doi: 10.1016/J.Ajog.2009.06.017. Artn 315.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S, Moren C, Lopez M, Coll O, Cardellach F, Gratacos E, Garrabou G. Perinatal outcomes, mitochondrial toxicity and apoptosis in HIV-treated pregnant women and in-utero-exposed newborn. AIDS. 2012;26(4):419–428. doi: 10.1097/Qad.0b013e32834f3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES. Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;51(2):333–348. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816f2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Ethier KA, Koenig LJ, Wilson TE, Walter EB, Fernandez MI. Infant birth weight among women with or at high risk for HIV infection: The impact of clinical, behavioral, psychosocial, and demographic factors. Health Psychology. 2000;19(6):515–523. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp KM, Brogly SB, Muenz DG, Spiegel HML, Conway DH, Scott GB, Pediat PTIM. Prevalence of Congenital Anomalies in Infants With In Utero Exposure to Antiretrovirals. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2012;31(2):164–170. doi: 10.1097/Inf.0b013e318235c7aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Goulet L, Lydon J, Seguin L, McNamara H, Dassa C, Koren G. Socio-economic disparities in preterm birth: causal pathways and mechanisms. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2001;15:104–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JS, Watts DH, Mofenson L, Stiehm ER, Harris DR, Bethel J, Fowler MG. Risk factors for preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth retardation in infants born to HIV-infected pregnant women receiving zidovudine. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 185 Team. AIDS. 2000;14(10):1389–1399. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy V, Ladner J, Nyiraziraje M, De Clercq A, Bazubagira A, Van de Perre P, Grp PHS. Effect of HIV-1 infection on pregnancy outcome in women in Kigali, Rwanda, 1992–1994. AIDS. 1998;12(6):643–650. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazzi MC, Palombi L, Nielsen-Saines K, Haswell J, Zimba I, Magid NA, Liotta G. Extended antenatal use of triple antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 correlates with favorable pregnancy outcomes. AIDS. 2011;25(13):1611–1618. doi: 10.1097/Qad.0b013e3283493ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LT, McNamara MJ, Milot AS, Halle T, Hair EC. The effects of father involvement during pregnancy on receipt of prenatal care and maternal smoking. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11(6):595–602. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonye AK, Hansen KS, Wamono F, Magnussen P. Barriers to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42(2):271–283. doi: 10.1017/S002193200999040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chidanyika A, Chipato T, Jaffar S, Padian N. The importance of male partner involvement for women’s acceptability and adherence to female-initiated HIV prevention methods in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):959–969. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9806-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndirangu J, Newell ML, Bland RM, Thorne C. Maternal HIV infection associated with small-for-gestational age infants but not preterm births: evidence from rural South Africa. Human Reproduction. 2012;27(6):1846–1856. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngui E, Cortright A, Blair K. An Investigation of Paternity Status and Other Factors Associated with Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Birth Outcomes in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(4):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM. Voluntary counseling and testing for couples: a high-leverage intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(11):1397–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin C, Spaenhauer A, Keiser O, Rickenbach M, Kind C, Aebi-Popp K, Cohort SMCH. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: analysis of Swiss data. HIV Medicine. 2011;12(4):228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Wilkinson DS. Impact of perceived stress, major life events and pregnancy attitudes on low birth weight. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(6):288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salihu HM, Stanley KM, Mbah AK, August EM, Alio AP, Marty PJ. Disparities in Rates and Trends of HIV/AIDS During Pregnancy Across the Decade, 1998–2007. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(3):391–396. doi: 10.1097/Qai.0b013e3181f0cccf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semrau K, Kuhn L, Vwalika C, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, Kankasa C, Thea DM. Women in couples antenatal HIV counseling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS. 2005;19(6):603–609. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163937.07026.a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffel S, Johnson D, Heuser R. A method of imputing length of gestation on birth certificates. Vital Health Stat. 1982;2(93):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitler JO. Father involvement, child health and maternal health behavior. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4–5):403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Rauh V, Barve SS, Hogan V, Sandman CA, Glynn L. Stress, infection and preterm birth: a biobehavioural perspective. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2001;15:17–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]