Abstract

Mitophagy, the autophagic degradation of mitochondria, is an important housekeeping function in eukaryotic cells and defects in mitophagy correlate with ageing phenomena and with several neurodegenerative disorders. A central mechanistic question regarding mitophagy is whether mitochondria are consumed en masse, or whether an active process segregates defective molecules from functional ones within the mitochondrial network, thus allowing a more efficient culling mechanism. Here, we combine a proteomic study with a molecular genetic and cell biology approach to determine whether such a segregation process occurs in yeast mitochondria. We find that different mitochondrial matrix proteins undergo mitophagic degradation at distinctly different rates, supporting the active segregation hypothesis. These differential degradation rates depend on mitochondrial dynamics, suggesting a mechanism coupling weak physical segregation with mitochondrial dynamics to achieve a distillation-like effect. In agreement, the rates of mitophagic degradation strongly correlate with the degree of physical segregation of specific matrix proteins.

Introduction

The autophagic clearance of defective or superfluous mitochondria, or mitophagy, is an important housekeeping function in eukaryotic cells1. In mammals, defects in mitophagy are associated with pathologies such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and type II diabetes. In yeast, a number of protocols have been developed under which mitophagy can be assayed. Mitophagy has been observed upon transfer of lactate-grown (respiring) cells in nitrogen replete medium to a nitrogen starvation medium containing glucose as carbon source (which shuts down respiration in S. cerevisiae)2 and upon administration of rapamycin to respiring cells3. Mitochondrial lesions have also been reported to induce mitophagy in yeast4,5.

We developed a distinct assay, stationary phase mitophagy, in which yeast cells undergo massive mitophagy in the absence of external intervention6. Stationary phase mitophagy shows distinct hallmarks of being a genuine quality control event and is distinct from starvation responses7. Using this protocol, Kanki et al and Okamoto et al carried out screens, which identified factors involved in mitophagy. Notably, these studies identified Atg32, an integral protein of the outer mitochondrial membrane that interacts with the autophagic machinery and is essential for mitophagy under all conditions8-10.

Mitochondria are widely acknowledged to be highly dynamic structures which constantly undergo fission and fusion, effectively forming a continuous, dynamic network that is constantly changing shape and distribution. Factors required for mitochondrial fusion as well as for mitochondrial fission have been identified in yeast, and corresponding orthologs occur in animal cells11,12. In cultured mammalian cells 85% of mitochondrial fission events result in the formation of one depolarized daughter mitochondrion and one hyperpolarized daughter mitochondrion13. The depolarized daughter is then given a “grace period” to regain membrane potential. Mitochondria that fail to recover do not re-fuse and are autophagocytosed 13. Pink1, a protein kinase that contains a mitochondrial targeting sequence, and Parkin, a ring-in between ring-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, are frequently mutated in familial Parkinson's disease14,15. Pink1 is constitutively imported into active mitochondria and degraded in the inter-membrane space, in a process that depends on the PARL protease16. Upon loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, Pink1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane17 and recruits parkin to the mitochondrial membrane17, leading to the ubiquitination of select substrates, including mitofusins18,19. These results independently suggested a role of mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of mitophagy in mammalian cells, and this was further corroborated by other groups20. In yeast, however, there have been conflicting reports on the role of mitochondrial dynamics in mitophagy9,3.

Proteomic analyses have been used to elucidate protein dynamics during general autophagic responses21. We were interested in applying this approach to stationary phase mitophagy, with the aim of testing specific hypotheses regarding the possible role of mitochondrial dynamics in mediating intra-mitochondrial segregation mechanisms. We indeed find that different mitochondrial matrix proteins have different proclivities to undergo mitophagic degradation, implying some sort of segregation mechanism. Strikingly, these different rates clearly correlate with a physical segregation of the same proteins within the matrix, a segregation which varies with individual protein species and is at least partly dependent on mitochondrial dynamics.

Results

Mitochondrial dynamics affect the kinetics of mitophagy

The role of mitochondrial dynamics in yeast mitophagy has been controversial3,22. Dnm1 is a dynamin-like protein required for mitochondrial fission23,24. Kanki et al9 reported loss of mitophagic activity in dnm1Δ mutants while Mendl et al3 claimed that mitochondrial fission is dispensable for mitophagy. However those studies used different stimuli to induce mitophagy: Kanki et al used a nitrogen starvation protocol coupled with a carbon source switch while Mendl et al induced mitophagy with rapamycin, a TOR inhibitor that has far-ranging metabolic effects.

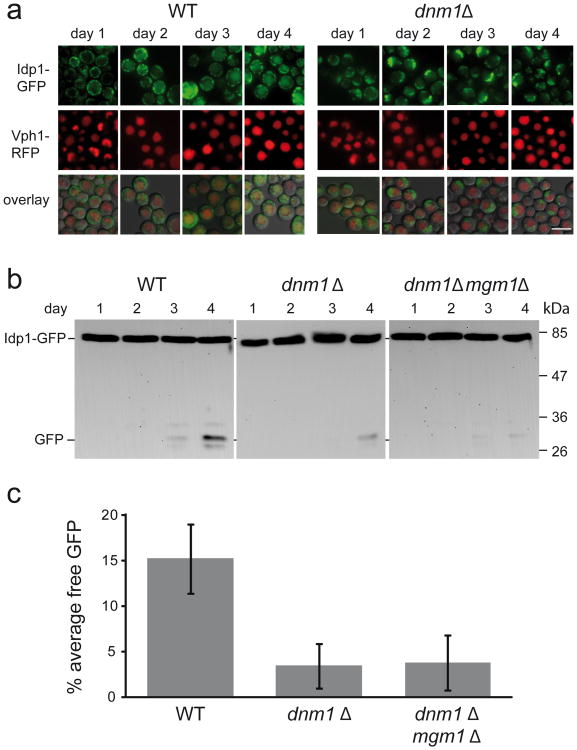

We determined the effect of DNM1 deletion on stationary phase mitophagy, using ectopically-expressed Idp1-GFP as a reporter7. Using fluorescence microscopy, we observe a clear defect in the vacuolar accumulation of GFP fluorescence in dnm1Δ cells (Figure 1a). To quantify this effect, western blotting with anti-GFP antibody coupled with densitometry was used to compare the levels of mitophagy in the two genotypes25, as judged by the percentage of signal converted into free GFP on day 4 of the experiment. As shown in Figure 1b and 1c, dnm1Δ cells show distinctly slower mitophagy kinetics relative to wild-type, with no mitophagy observed at day 3 of the incubation, and the percent of the signal which was converted into free GFP at the 4 day time point was approximately 5-fold lower in the dnm1Δ mutant relative to wild-type (Figure 1c; p<0.005, ANOVA). This result is consistent with the data of Kanki et al.9. A similar effect was observed in fis1Δ cells (Supplementary Figure S1), supporting the idea that mitochondrial dynamics is required for efficient mitophagy.

Figure 1. The kinetics of stationary phase mitophagy are determined by mitochondrial dynamics, not size.

a. Wild-type and dnm1Δ cells expressing Vph1-RFP and Idp1-GFP were grown in minimal SD medium and transferred to lactate medium at an initial density of OD600 0.08. The cells were then sampled daily and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (100x objective) during stationary phase mitophagy in lactate medium. Scale bar= 5μm. b. Wild-type, dnm1Δ and dnm1Δ mgm1Δ mutants were grown in SL medium as described in Materials and Methods, and samples (10 OD600 units) were taken at each time point. Protein extracts were prepared and equal protein amounts (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody. c. Quantification of the percent free GFP at the day 4 time point in each of the three strains analyzed in b, using 4 independent experiments for each strain. Error bars indicate standard deviation. ANOVA, p<0.001; N=4.

The observation of a significantly slower mitophagy in dnm1Δ mutants defective in mitochondrial fission may indicate that the autophagic machinery is unable to process large mitochondrial compartments26, or that mitochondrial dynamics functions to segregate defective components. To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested a dnm1Δ mgm1Δ double mutant. Mgm1 is a dynamin homolog that is required for mitochondrial fusion, and the double mutants have normal mitochondrial morphology, but lack mitochondrial dynamics27-29. If mitochondrial size was determining the kinetics of mitophagy, then the double mutants would be expected to display increased mitophagy relative to dnm1Δ cells. Conversely, if mitochondrial dynamics is responsible then we expect the double mutants to display kinetics similar to the dnm1Δ single mutant, or even a reduced rate of mitophagy. The result, as shown in Figures 1b and 1c, is consistent with mitochondrial dynamics, not mitochondrial size, as the main determinant of the rate of mitophagy under our working conditions.

Proteomic analyses of protein dynamics during mitophagy

We were interested in determining whether a global analysis of protein dynamics during stationary phase mitophagy could identify candidate mitochondrial proteins which showed divergent rates of mitophagy, and in testing the relationship of this discrimination to mitochondrial dynamics. To obtain a global view of stationary phase mitophagy, we adapted the SILAC protocol to yeast cells undergoing stationary phase mitophagy (see Methods and Figure 2a), comparing wild-type cells with three mutants, which are defective in different aspects of mitophagy: pep4Δ, atg32Δ, and aup1Δ (Figure 2b). Pep4 is a vacuolar protease that is required for activation of zymogens in the vacuolar lumen30. Atg32 is an integral protein of the mitochondrial outer-membrane which is essential for mitophagy but not for other aspects of cell function, including other types of autophagy10,31. Aup1 is a mitochondrial PP2C-type protein phosphatase that is conserved between yeast and mammalian cells, and was implicated in specific aspects of stationary phase mitophagy6,32. We performed minimally two biological replicates for all experiments, and the respective quantitative proteomics data correlated well, with an overall Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.71 (Figure 2c, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). We were able to obtain good quantitative coverage with 1551 proteins quantified in all time-points in at least one yeast strain and 785 proteins with a full time-course profile across all yeast strains (Figure 2d, Supplementary Table S1). From Figure 2e it is apparent that the individual time-points for each strain cluster closely together, indicating that the response of the proteome is robust across the time-course for the majority of proteins. In contrast, the data from the different mutants diverge in the three dimensions of the PCA, illustrating that the mutations have distinct effects on the yeast proteome. Another observation is that atg32Δ is in close proximity to wild-type, whereas pep4Δ and particularly aup1Δ are more distant from the wild-type. This is consistent with the nature of the atg32Δ mutation, which only affects the process of mitophagic engulfment, whereas Pep4 and Aup1 have functions not restricted to mitophagy.

Figure 2. Characterization of stationary phase mitophagy in wild-type and knock-out strains by quantitative proteomics.

a. Global protein abundance dynamics was analyzed in four different of S. cerevisiae strains (WT, pep4Δ, atg32Δ, and aup1Δ) using SILAC. Global protein levels were analyzed over five day incubations in lactate-based minimal medium. b. To quantify changes in protein dynamics, each of the strains was labeled in lactate-based minimal media containing either normal lysine (Lys0), lysine-D4 (Lys4) or lysine-13C6-15N2 (Lys8). Samples (10 OD600 units) were taken at day 1 (Lys0), day 2 (Lys4), day 3 (Lys8), day 4 (Lys4) and day 5 (Lys8; see Methods). The mixed lysates were then separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE and the proteins were digested with LysC. The resulting peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS and the raw data was processed by MaxQuant. We performed two biological replicates of the complete time-course experiments for each mutant, and three replicates for the wild-type, and observed good reproducibility for all the individual experiments (Supplementary Figure S2). c. Density plot of the reproducibility of biological replicates. d. Venn diagram of the number of proteins identified from the different yeast strains. e. Principal component analysis of the Log2 transformed abundance changes of proteins identified in all strains and all time points.

Spatial and temporal analysis of protein level dynamics

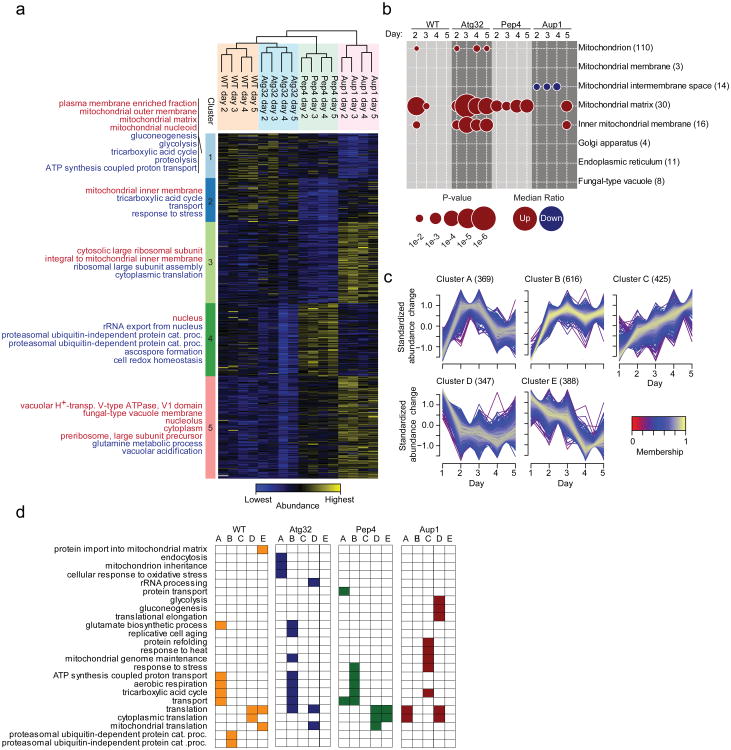

To summarize the regulation of the proteome in the four yeast strains we subjected the pooled results to hierarchical clustering and grouped proteins with similar dynamics by k-means clustering (Figure 3a & Supplementary Figure S3). Hierarchical clustering confirms that the atg32Δ strain is most similar to wild-type followed by pep4Δ, while aup1Δ shows the highest divergence relative to wild-type. The k-means clustering allowed partitioning of the proteins into five groups, each with characteristic dynamics. We tested for enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms in each of these clusters, compared to the proteins in the remaining four clusters. Distinct functional groups of proteins are enriched in each cluster (Figure 3a; for graphic depiction of the clusters see Supplementary Figure S3). Deletion of PEP4 and AUP1 causes an accumulation of a large group of proteins that are found in clusters 3, 4 and 5. The function of the proteins in these clusters includes mitochondrial processes but also additional cellular processes taking place in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. In clusters 1 and 2, which contain proteins with the lowest abundance in the aup1Δ or the pep4Δ strains, we found a clear enrichment of mitochondrial proteins and processes related to mitochondrial sub-compartments. To further explore the regulation of different mitochondrial sub-compartments we tested for significant differences in the average ratio of proteins associated with specific mitochondrial sub-compartments compared with the remaining proteins (Figure 3b). We found a significant accumulation of mitochondrial matrix proteins on day 2 in the wild type strain, and interestingly, this accumulation was dramatically expanded in the atg32Δ mutant. Prolonged accumulation of mitochondrial matrix proteins was also observed in the pep4Δ strain. In contrast, we observed a significant depletion of mitochondrial inter-membrane space proteins in the aup1Δ strain and no accumulation of matrix proteins on day 2. For comparison, we applied this type of analysis to proteins of the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and the vacuole, but found no significant effect. Thus, it seems that the observed accumulation or depletion of proteins in the mitochondrial sub-compartments is specific, and is not a cell-wide phenomenon.

Figure 3. Temporal dynamics of the yeast proteome during stationary phase mitophagy.

a. Ratios from proteins with quantifications from all samples were log2 transformed and z-score normalized. Columns containing data from the different samples were clustered hierarchically and rows that contained protein entries were clustered by k-means. The proteins in each k-means cluster were tested for enrichment of GO CC (indicated in red) and GO BP (indicated in blue) terms. b. Proteins associated with different cellular compartments were sequentially extracted and the average of their ratios were compared with averages of remaining proteins. c. The temporal dynamics of the protein ratios in each mutant was clustered by Fuzzy c-means. d. GO BP enrichment analysis of proteins in the different clusters compared to the remaining proteins.

To obtain a more detailed view, we clustered all time-course profiles independently (Figure 3c) and obtained clusters corresponding to distinct temporal dynamics. We again applied GO term enrichment analysis to assess if particular biological processes were associated with the dynamics summarized in the clusters (Figure 3d). We identified 24 GO terms that were significantly enriched. Although some were exclusive to a specific mutant, such as the up-regulation of gluconeogenesis-related proteins in the aup1Δ strain, enrichment of GO terms for mitochondrial processes in clusters that were distinct from the WT profile were found in all three mutants. What particularly attracted our attention was that key mitochondrial processes such as TCA cycle were enriched in different clusters (cluster B/C) in the mutants compared with the wild-type (cluster A). Proteins in all three clusters rapidly accumulate, but proteins in cluster A return to a level closer to the starting point on day 4, whereas proteins in clusters B/C remain at elevated levels or increase further, possibly reflecting defective mitophagy in the mutant strains.

Selective mitophagic degradation and mitochondrial dynamics

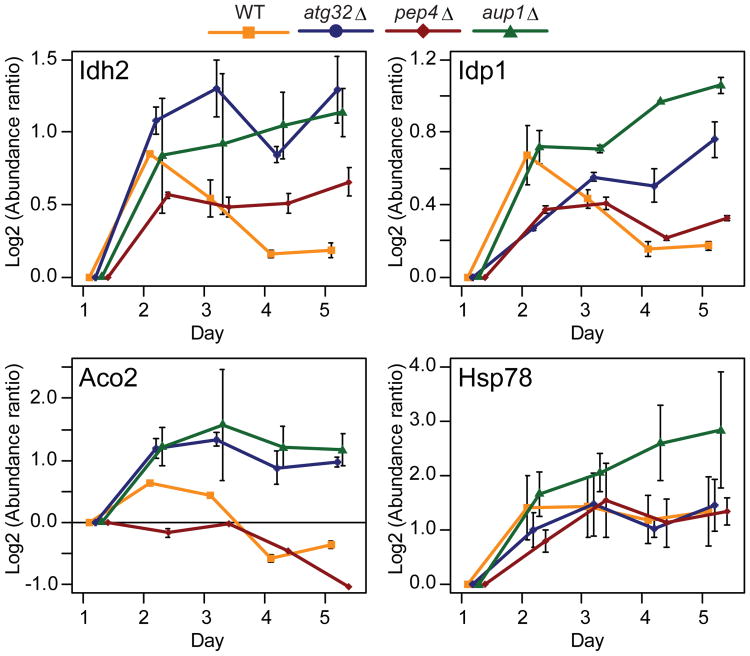

Proteomic analysis allowed us to identify proteins whose steady-state levels and dynamics were different between WT cells and the three mutant backgrounds. However, we cannot conclude from the SILAC data alone that these are all due to differential rates of mitophagic degradation. We chose several candidate mitochondrial matrix proteins whose levels showed extreme behavior under these conditions, for further study. Pet9, Idh2, Idp1 and Aco2 show a decrease in abundance (when analyzed in the wild-type background) that is not observed, or is weaker, in atg32Δ, aup1Δ, and/or pep4Δ mutants. It was convenient that this group included Idp1, which we previously used the C-terminally tagged version of this protein as a mitophagy marker in a plasmid-based ectopic expression system (Figure 17). In contrast, the levels of Hsp78 increase in all of the genetic backgrounds tested (Figure 4). We tagged the reading frames of these proteins with a C-terminal GFP module using the chromosomal cassette integration method33, utilizing transcription from the endogenous promoter to drive gene expression. We found Pet9-GFP to be non-functional, precluding it from further analysis. We scored the appearance of free GFP in the vacuolar lumen following a 7-day incubation protocol in lactate-based medium, as previously reported7, by western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies (Figure 5), as well as by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 6). The release of free GFP in the vacuolar lumen is an established assay for mitophagy, and is due to selective degradation of the endogenous mitochondrial protein moiety of the chimera in the vacuole34. Deletion of autophagy genes, such as ATG1 and ATG32, abolished the appearance of free vacuolar GFP in immunoblots and by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5c and Supplementary Figure S4), confirming the robustness of the assay across multiple protein chimeras, and the dependence of our readout on mitophagy. As shown in Figure 5a, Aco2, Idp1, and Hsp78 all showed clear signs of mitophagy, as judged by the release of free GFP. However Aco2-GFP and Idp1-GFP -expressing cells reproducibly showed significantly higher levels of accumulated free GFP, relative to Hsp78-GFP after 7 d in respiratory medium (60% vs 20%). Idh2 on the other hand, showed extremely low levels of free GFP during these incubations (<5%), suggesting that this protein is being excluded from undergoing mitophagy. While immunoblotting showed that the steady-state levels of Idh2 decreased with time, as predicted from the SILAC data, this decrease must occur by a non-autophagic process. One possible explanation for these data is that mitochondrial matrix proteins are segregated in a way that leads to differential rates of degradation through mitophagy. The fact that lack of release of free GFP (Figure 5b) is concomitant with a lack of appearance of vacuolar GFP (Figure 6) also rules out the possibility that the differences in the release of free GFP are due to differential susceptibility to cleavage or indirect effects on vacuole function, since in those cases we would observe vacuolar GFP even if free GFP is not observed by western blotting.

Figure 4. Temporal dynamics of selected proteins.

A comparison of the SILAC-derived abundance as a function of time, for several proteins which either show differential behavior between WT and the mutants (Idh2, Idp1, Aco2) and proteins which behave similarly between all the genetic backgrounds tested (Hsp78). Shown are mean protein ratios (two replicates for mutants, three replicates for WT), error bars indicating peptide-based relative standard deviations.

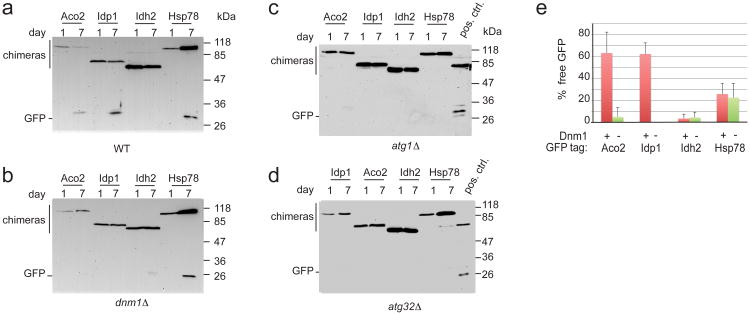

Figure 5. Selective mitophagy of matrix proteins depends on mitochondrial dynamics.

Wild type (a), dnm1Δ (b) and atg1Δ cells (c) and atg32Δ cells (d) expressing chromosomally-tagged GFP chimeras of Aco2, Idh2, Idp1 and Hsp78 were incubated in SL medium for 7 days and 10 OD600 units were sampled at day 1 and day 7, and processed for immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies as described in the Methods section. Positive control used in panels c and d was from dnm1Δ cells expressing Idp1-GFP from a plasmid at 4 days incubatin (Figure 1b, lane 4). Release of free GFP in wild-type cells is reproducibly variable between these reporters, and varies between 0 (Idh2) and 60% (Aco2). e. Densitometric quantification of the release of free GFP (as % of total signal) in 4 independent experiments, comparing the results between wild-type and dnm1Δ cells. Bars denote standard deviation (n=4).

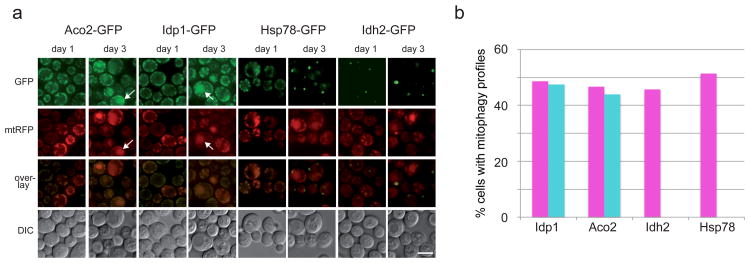

Figure 6. Intra-mitochondrial segregation and differential mitophagic targeting.

a. Cells expressing chromosomally-tagged GFP chimeras of Aco2, Idh2, Idp1 and Hsp78 as wells as a plasmid-borne (pDJB12), mitochondrially targeted RFP (mtRFP) were incubated in SL-leucine medium for 3 days and imaged daily. Aco2 and Idp1 show clear mitophagic targeting (white arrows point at specific examples) by day 3, while Idh2 and Hsp78 show weak or no mitophagy. In addition, Idh2 and Hsp78 show different degrees of segregation relative to the mtRFP marker, while Idp1-GFP and Aco2-GFP show a near-complete co-localization with mtRFP. Scale bar, 5μm. b. Quantification of the frequency of mitophagy from (a); the percentage of cells showing mitophagic profiles in the red (magenta bars; plasmid-borne mtRFP) or green (turquoise bars; integrated C-terminal GFP chimerae) was calculated for each GFP chimera. Idp-GFP, red N=76, green N=82; Aco2-GFP, red N=79, green N=82; Idh2-GFP, red N=72, green N=72; Hsp78-GFP, red N=70, green N=70.

If mitochondrial dynamics plays a role in determining the differential rates of mitophagy observed for these proteins, then the dnm1Δ mutation should produce differential effects on the GFP-tagged chimeras. As shown in Figures 5b and 5e, this is indeed the case: The percentage of free GFP produced is down to 0-5% for both Aco2 and Idp1 when assayed in the dnm1Δ background, while it is essentially unchanged for Hsp78 (20%) and Idh2 (5%). Thus, we may conclude that mitochondrial dynamics is required for the kinetic distinction between Hsp78 and Idh2 on the one hand, and Aco2 and Idp1 on the other hand. It should also be noticed that the panels 5a and 5d broadly confirm the predictions of the respective proteomic analyses of WT and atg32Δ cells (Figure 4); for example the levels of full-length Aco2-GFP clearly go down in WT but not in the mutant, while Hsp78 is clearly induced in all backgrounds.

Physical segregation of mitochondrial matrix proteins

If Hsp78 and Idh2 are kinetically distinct from Idp1 and Aco2, then, assuming our hypothesis is correct, one expects this to be reflected in some form of physical segregation. Indeed, when following the fluorescence pattern of Hsp78-GFP, Idh2-GFP, Idp1-GFP, and Aco2-GFP in cells co-expressing a generic mtRFP from an extrachromosomal plasmid, we observe patterns that are consistent with this prediction (Figure 6). Over a 3 day incubation on synthetic lactate medium, the cytoplasmic signal of both Idp1 and Aco2, which undergo efficient mitophagy, fully co-localizes with the mtRFP dots, indicating that they are present in an equivalent representation throughout the mitochondrial network. In addition, one observes at day 3 in these same cells, the appearance of vacuolar accumulation of both RFP and GFP as predicted from the immunoblotting data. However, Idh2-GFP, which shows little or no mitophagic degradation, is distinctly restricted to one or two very brightly -stained foci per cell. While these foci co-fluoresce in red, indicating that they are part of the mitochondrial network, Idh2-GFP is clearly not evenly distributed in the network. An intriguing pattern is observed for Hsp78-GFP expressing cells. On day 1 these cells show a uniform mitochondrial distribution that is similar to that observed for Idp1 and Aco2, with very good co-localization of the GFP and RFP signals. Gradually, however, the Hsp78-GFP signal concentrates in one or two discrete foci, which although not as powerfully bright as those observed for Idh2-GFP, represent the bulk of the cellular Hsp78 content. Again, while these foci co-fluoresce with mtRFP, the bulk of the mtRFP-positive dots do not show any significant green fluorescence by the third day of the experiment, indicating a time-dependent segregation of Hsp78 within the mitochondria, which coincides with the onset of stationary phase mitophagy. A quantification of the signal overlaps of Figure 6a is given in Supplementary Table S1. These results correlate with the release of free GFP in the sense that Idh2-GFP exhibits the most extreme behavior both with regard to stability and with regard to physical segregation, while HSP78-GFP is intermediate in both cases. Idp1-GFP and Aco2-GFP, which appear to be uniformly distributed in mitochondria, are also the most susceptible to mitophagic degradation. Interestingly, we find that the Hsp78-GFP puncta, as well as the Idh2-GFP puncta, show partial co-localization with the ERMES35,36 marker Mdm34 (Supplementary Figure S5).

Mitochondrial dynamics affects matrix protein segregation

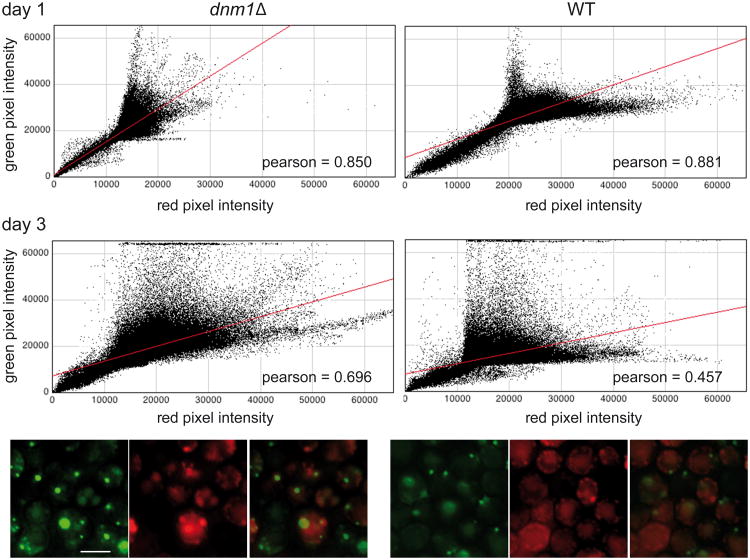

If mitochondrial dynamics plays a role in the time-dependent segregation of Hsp78-GFP, then dnm1Δ cells should show reduced segregation, as measured by the degree of co-localization of mtRFP and Hsp-78. While deletion of DNM1 does not abolish the formation of intensely fluorescent Hsp78-GFP puncta, it does quantitatively reduce the recruitment of Hsp78-GFP molecules from the general matrix milieu to these puncta, as shown by channel correlation graphs (Figure 7). In these experiments we can see that the relative co-localization of mtRFP and Hsp78-GFP is reduced between day 1 (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.881) and day 3 (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.457). This is due to the accumulation, on day 3, of high-intensity GFP channel pixels that do not accumulate RFP fluorescence to the same extent. In contrast, dnm1Δ cells show a much milder change, from a correlation coefficient of 0.85 to 0.696. While high intensity GFP channel pixels do accumulate in the mutant on day 3, many of them are also correlated with increased red channel fluorescence, in contrast with the situation observed in wild-type cells where the high intensity regions in the green channel rarely coincide with high intensity red regions. This result confirms that loss of mitochondrial fission impacts the segregation of Hsp78-GFP from the general matrix milieu.

Figure 7. Decreased segregation of Hsp78-GFP in dnm1Δ cells.

Wild-type and dnm1Δ cells expressing integrated Hsp78-GFP and plasmid-borne mtRFP were grown on lactate medium for 3 d. Cells were imaged daily and the images were analyzed using ImageJ as described in “Methods”. Graphs illustrate the distribution of pixels associated with specific values of RFP and GFP channel intensities, respectively. Diagonal concentrations of dots indicate spatial correlation between the signals. The colored photographic panels at the bottom illustrate the increased intensity correlation of the two channels at the 3 day time point in the dnm1Δ mutant, relative to the wild-type cells. Scale bar, 5μm.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we have identified a role for mitochondrial dynamics, as opposed to mitochondrial size, in regulating the rate of mitophagy. By comparing the dynamics of mitochondrial protein levels during stationary phase mitophagy, we found that the abundance of mitochondrial matrix proteins shows differential time-dependent behavior during stationary phase mitophagy, and that a subset of these proteins further shows differential dynamics in WT cells relative to mutants defective for different aspects of mitophagy. In the case of the proteins that were more closely analyzed in this study, these differential dynamics also appear to reflect differential rates of mitophagy in wild-type cells (figure Figure 5). Thus, mitochondrial matrix proteins undergo mitophagy with differential kinetics. This result strongly supports the notion of active segregation within the matrix. How would we envisage this? One hypothesis is that mitochondrial fission and fusion are loosely coupled with a weak segregation mechanism and that upon many rounds of fission and fusion, defective components will be ‘distilled’ from the network and earmarked for degradation32. In agreement, we find that the kinetic distinction between slowly-degraded mitochondrial matrix proteins such as Idh2 and Hsp78 on the one hand, and the rapidly degraded Idp1 and Aco2 on the other hand, is clearly a function of mitochondrial dynamics (Figure 5). When using an ectopically-expressed reporter, we find that loss of mitochondrial dynamics leads to a significantly slower onset of mitophagy (Figure 1). This reduction can be uncoupled from general effects on mitochondrial morphology, since a double dnm1Δ mgm1Δ mutant does not show any signs of rescue for this phenotype (Figure 1c), even though it suppresses the mitochondrial morphology phenotype of the dnm1Δ mutation27,28.

The segregation of Hsp78-GFP and Idh2-GFP into distinct puncta seems to partly overlap with the distribution of Mdm34, a component of the ER-mitochondrial tethering complex (ERMES35,36; Supplementary Figure S5). As the ER-mitochondria junctions have been suggested to play a role in mitochondrial fission37,38, our results may also hint at a role of these junctions in the segregation of matrix proteins.

Intra-mitochondrial segregation of matrix proteins has been observed before, for example with specific mutant alleles of Ilv5, a protein required both in branched amino acid synthesis as well as in mitochondrial genome maintenance39. Interestingly, under some conditions the same mutant protein underwent specific, Pim1-dependent degradation that was in turn affected by Hsp78 function39. Hsp78 (and perhaps Idh2) segregation may also indicate localization of select proteins to sites of Pim1-dependent proteolysis. This would explain the mitophagy-independent reduction that we observe in Idh2 levels, if segregation is related to Pim1-dependent degradation of Idh2. In addition, oxidized yeast aconitase segregates away from non-oxidized aconitase during mitosis, with the oxidized molecules preferentially being sequestered in the mother cell and away from the budding daughter cell40.

One important corollary of the present study is that the outcome of any mitophagy experiment strongly depends on the nature of the reporter(s) that are chosen to represent mitophagic degradation. Even more surprising however is the fact that for a given individual protein, an endogenously expressed reporter can behave somewhat differently from ectopically overexpressed molecule. Note that the effect of the dnm1Δ mutation on the endogenous Idp1-GFP appears to be absolute, in the sense that no free GFP is observed even after 7 days of incubation (Figure 5). In contrast, an ectopic, overexpressed copy of Idp1 is slowly transported to the vacuole even in dnm1Δ cells (Figure 1) and free GFP is observed after 4 days. This apparent discrepancy may actually hint at an underlying segregation mechanism: If functioning mitochondrial matrix proteins are tightly ensconced in a gel-like matrix of interacting proteins, and if we assume that malfunctioning proteins are not associated with this matrix, then this distinction may provide a mechanism for a fission-coupled segregation effect. Likewise, over-expressing a protein beyond the stoichiometric balance dictated by the matrix, as we have done with Idp1-GFP in Figure 1, would also lead to increased accumulation of ‘unattached’ protein that would be more susceptible to mitophagic degradation- even in the absence of a fully functional segregation mechanism.

While this manuscript was under revision, Mao et al41 published that Dnm1 directly interacts with Atg11, a component of the autophagic machinery, and that this interaction is important for efficient starvation-induced mitophagy. While this result clearly supports a direct role for Dnm1 in regulating mitophagy, further work is required to understand how this interaction may be linked to the segregation and differential degradation of matrix components during stationary phase mitophagy.

In mammalian cells, mitochondrially-derived, lysosome-bound vesicles were shown to contain differential representation of mitochondrial proteins derived from different sub-compartments42,43, as well as differential representation of inner membrane ETC components. While our results also indicate a form of segregation, they are also distinct in that we find evidence for segregation of matrix proteins amongst themselves, during mitophagy as a mechanism for selectivity. In addition, we find clear evidence for an autophagic mechanism of transport of these components to the vacuole, while the mechanism identified by the Soubannier et al studies is clearly independent of autophagy as well as of the mammalian Dnm1 orthologue, Drp143,44. The recent study by Vincow et al45 (a comparison of that study with our results is available in Supplementary Figure S6), also found variations in the degree to which different mitochondrial proteins accumulate in response to a block of mitophagy. Although that study did not demonstrate differential mitophagy of those proteins, it stands to reason that selectivity is a conserved feature of mitophagy across the eukaryotes. In support of this, a recent proteomic study of protein turnover in mouse mitochondria46 found that the half -life of mitochondrial proteins varied from hours to months. Since, in the absence of segregation, the rate of mitophagy would predict a uniform turnover in the range of hours and days13, one is tempted to invoke segregation and selective mitophagy in this case as well. While it remains to be seen whether mitochondrial dynamics orchestrate a similar segregation during mammalian mitophagy, the conservation of the fission-fusion machinery, coupled with the data of Twig et al13. strongly suggest that these phenomena are conserved.

Methods

Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Hylabs (Rehovot, Israel) and the relevant sequences appear in Supplementary Table S2.

Plasmids

Plasmids pHAB10247 and pDJB117 were previously described. Plasmid pHAB129 was generated by cloning a PacI-AscI fragment from pHAB102 into PacI-AscI digested pFA6a-kanMX633. To generate plasmid pDJ12, the mRFP1 open reading frame48 was amplified with oligonuceotides F1 and R1, containing flanking BglII and XhoI restriction site extensions, respectively. PYX142 49 was digested with with BglII and XhoI to discard the GFP reading frame, and the gapped plasmid was ligated into the BglII-XhoI digested mRFP insert to yield pDJ12.

Yeast strains

Deletion mutants and epitope tagged strains were constructed by the cassette integration method 33, using plasmids pHAB102, pHAB152 6 or pFA6a-KanMX6 33 as template, unless otherwise specified. Strain HAY77 (MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-Δ 200 trp1-Δ 901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ 9) 50 was used as the wild-type standard in these studies. All knockout strains were verified by PCR. To generate strain HAY881 (dnm1Δ), oligonuceotides F2 and R2 (see Supplementary Table S2) were used to amplify the S. pombe HIS5 gene and generate a knockout cassette. The PCR product was transformed into HAY77 to generate strain HAY881. To generate strain HAY706, the Vph1 ORF was C-terminally tagged with mRFP 48. Oligonucleotides F3 and R3 were used to amplify the mRFP ORF joined to the S. pombe HIS5 gene, generating a C-terminal tagging cassette. The amplification product was used to transform strain HAY77.

To generate strain HAY1197, strain HAY706 was transformed with a KO cassette targeting dnm1, which was amplified from plasmid pHAB152 (encoding G418 resistance) using the oligonuceotides F4 and R4. Strains HAY395 (atg1Δ)47 and HAY809 (aup1Δ)7 were previously described. Strain HAY1097 (atg32Δ) was generated from HAY77 by transforming a KO cassette encoding the S.p. HIS5 gene into the ATG32 locus. The cassette was produced by PCR, using plasmid pHAB102 as template and the oligonucleotides F5 and R5 as primers. Strain HAY1156 (dnm1Δ mgm1Δ) was generated from strain HAY881 by transforming with an MGM1 KO cassette encoding the S.p. HIS5 gene and containing flanking sequences from the MGM1 open reading frame. The cassette was produced by PCR, using plasmid pHAB129 (encoding G418 resistance) as template and the oligonucleotides F6 and R6 as primers. Strains HAY1161, HAY1164, HAY1165, HAY1167, were generated by transforming strain HAY77 with PCR cassettes amplified from pHAB152. The oligonucleotides used were as follows: For HAY1161, F7 and R7; for HAY1164, F8 and R8; for HAY1165, F9 and R9; for HAY1167, F10 and R10. Strains HAY1245 (HSP78-GFP::G418 MDM34-RFP::HIS5) and HAY1246 were generated from strains HAY1161 and HAY1167, respectively, by transforming with a PCR product amplified from plasmid pHAB147 using the oligonuceotides F11 and R11.

Growth conditions

Yeast were grown in synthetic dextrose medium (SD; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, auxotrophic requirements and vitamins as required) or in synthetic lactate medium (SL; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% lactate pH 6, 0.1% glucose, auxotrophic requirements and vitamins as required). All culture growth and manipulations were at 26°C unless indicated otherwise.

Chemicals and antisera

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Rehovot, Israel) unless otherwise stated. Custom oligonucleotides were from Hy-Labs (Rehovot, Israel) or IDT (Bet Shemesh, Israel). Anti-GFP antiserum was from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX). HRP -conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA). Lysine-D4 and lysine-13C6 15N2 were purchased from Silantes GmbH (Munich, Germany).

Preparation of whole cell extracts for western blot analysis

Cells (10 OD600 units) were treated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Sigma T0699) at a final concentration of 10% and washed three times with acetone. The dry cell pellet was then resuspended in 100 μl cracking buffer (50 mM tris pH 6.8, 3.6 M urea, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) and vortexed in a Disruptor Genie (Scientific Instruments, Bohemia, NY) at maximum speed with an equal volume of acid-washed glass beads (425-600 μm diameter), for 30 min. Unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation at 13,000x g for 5 minutes and Protein was quantified using the BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford Ill). An equal volume of 2X SDS loading buffer (100 mM tris pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 500 mM β-mercaptoethanol was added to the supernatant. The samples (20 μg protein per lane) were incubated at 70°C for 5 min prior to loading on gels. ImageJ software was used for band quantification.

Fluorescence microscopy

Typically, culture samples were placed on standard microscope slides (3 μl) and viewed using a Nikon E600 upright fluorescent microscope equipped with a 100x Plan Fluor objective, using a FITC fluorescent filter (for viewing GFP fluorescence) or a Cy3 filter (for viewing FM4-64). To achieve statistically significant numbers of cells per viewing field in some pictures, high cell densities were achieved by sedimenting 1 ml cells for 30 s at 500x g and resuspending the pellet in 20 μl of medium. Pictures were taken with a Photometric Coolsnap CCD camera. For quantitative analysis of co-localization we used ImageJ software with the Just Another Co-localization Plugin (JACP) 51 plugin. Representative fields, each encompassing >200 cells, were analyzed in terms of channel intensity correlation by plotting cytofluorograms and calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient and Mander's coefficients. For quantitative estimates of mitophagic trafficking, mitophagy was scored as the appearance of mitochondrial fluorescent proteins in the vacuolar lumen (defined as green fluorescence overlapping the vacuole).

SILAC labeling

Yeast cultures were grown to saturation in SD medium, washed in sterile DDW, and resuspended in SL lacking lysine at a density of 0.08 OD600. The cell suspension was divided into three equal parts. These were each supplemented with differentially isotopically substituted lysine as follows: regular lysine, lysine +4 dalton (lysine-D4) and lysine +8 dalton (lysine-13C6 15N2) to a final concentration of 30 mg/l (approximately 200 μM). Samples (10 OD600 units) were withdrawn daily, TCA was added to 10% (final concentration), washed 3 times with cold acetone, and air dried. The samples from days 1,2,3 were combined in equal amounts prior to protein extraction, as were the samples from days 1, 4, 5. Finally, the samples were air-dried.

Mass spectrometry and data processing

SILAC labeled samples were dissolved in 80 μl cracking buffer with acid wash glass beads. After 30 sec sonification 20 μl SDS loading buffer were added and the pH was adjusted with 1 M NaOH. Samples were reduced (1 mM DTT) and alkylated (5.5 mM iodoacetamide). Protein mixtures were separated by SDS-PAGE using 4-12% Bis-Tris mini gradient gels (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). The gel lanes were cut into 10 equal slices, proteins therein in-gel digested with LysC (Wako), and the resulting peptide mixtures were desalted on STAGE tipps. Desalted samples were fractionated by nanoscale-HPLC on an Agilent 1200 connected online to a LTQ-Orbitrap XL (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were separated over a linear gradient from 10-30% ACN in 0.5% acetic acid with a flow rate of 250 nl/min. All full-scan acquisition was done in the FT-MS part of the mass spectrometer in the range from m/z 350-2,000 with an automatic gain control target value of 106 and at resolution 60,000 at m/z 400. MS acquisition was done in data-dependent mode to sequentially perform MS/MS on the five most intense ions in the full scan in the LTQ using the following parameters. AGC target value: 5,000. Ion selection thresholds: 1,000 counts and a maximum fill time of 100 ms. Wide-band activation was enabled with an activation q = 0.25 applied for 30 ms at a normalized collision energy of 35%. Singly charged and ions with unassigned charge state were excluded from MS/MS. Dynamic exclusion was applied to reject ions from repeated MS/MS selection for 45 s.

All recorded LC-MS/MS raw files were processed together in MaxQuant 52 with default parameters. For databases searching parameters were mass accuracy thresholds of 0.5 (MS/MS) and 6 ppm (precursor), maximum two missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation (C) as fixed modification and deamidation (NQ), oxidation (M), and protein N-terminal acetylation as variable modifications. Enzyme specificity was LysC. MaxQuant was used to filter the identifications for a FDR below 1% for peptides, sites and proteins using forward-decoy searching. Match between runs were enabled with a retention time window of 2 min.

From complete proteomics experiments 240 samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. We identified 2603 protein groups, corresponding to approximately half of all predicted yeast ORFs, with the proteins being identified on average by 9 peptides covering 28% of the protein sequence.

Clustering and Gene Ontology enrichments analysis

To compare the response to the induction across the four strains the protein quantitation ratios from each protein from the 16 samples were Log2 transformed and standardized (z-scored) and the proteins were partitioned into five clusters by k-means clustering. For enrichment analysis Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process and Cellular Compartment terms were retrieved from the UniProt database using GProX 53 and Fisher's exact test followed by Benjamini and Hochberg p-value adjustment were used to extract terms enriched in each cluster when tested against the remaining five clusters. A p-value after adjustment below 0.05 and at least 5 occurrences in the cluster were required to assign a GO term enriched in a cluster. To address the temporal dynamics of the induction the ratios for the individual time-points were clustered together for all strains using the fuzzy c-means algorithm using in GProX 53 with default parameters. Subsequently, for the response in each strain the GO term enrichment analysis were performed as described above with same parameters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Orian Shirihai, Leslie Kane, Ian Holt and J.-C. Martinou for stimulating and fruitful discussions, members of the Youle lab for support and encouragement, and Dikla Journo-Eckstien for technical assistance. We also thank J.-C. Martinou and Zvulun Elazar for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was funded by Israel Science Foundation grants 1016/07 and 422/12 to H.A., by the intramural program of NINDS, and by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments through Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS), School of Life Sciences – LifeNet (JD) and the Center for Biological Signaling Studies (BIOSS, JD), by grants DE 1757/2-1 from the German Research Foundation, DFG, and through GerontoSys II – NephAge (031 5896 A) from the German Ministry for Education and Research, BMBF (JD), and by a grant from the Danish Natural Sciences Research Council (KTGR).

Footnotes

Author contributions: HA initiated the project, planned experiments, carried out experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. MZ carried out protein extract processing and MS analyses. KTR performed statistical analyses of MS data and generated figures. RJY helped plan experiments. JD planned experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

The authors state that they have no competing financial interests

Accession codes: MS raw data files and respective information can be downloaded from the Peptide Atlas Data Repository (http://www.peptideatlas.org/PASS/PASS00341) using the password FV8467pe 54

References

- 1.Lemasters JJ. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2005;8:3–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissova I, Deffieu M, Manon S, Camougrand N. Uth1p is involved in the autophagic degradation of mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39068–39074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendl N, et al. Mitophagy in yeast is independent of mitochondrial fission and requires the stress response gene WHI2. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1339–1350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priault M, et al. Impairing the bioenergetic status and the biogenesis of mitochondria triggers mitophagy in yeast. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1613–1621. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowikovsky K, Reipert S, Devenish RJ, Schweyen RJ. Mdm38 protein depletion causes loss of mitochondrial K+/H+ exchange activity, osmotic swelling and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1647–1656. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tal R, Winter G, Ecker N, Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H. Aup1p, a yeast mitochondrial protein phosphatase homolog, is required for efficient stationary phase mitophagy and cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5617–5624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Journo D, Mor A, Abeliovich H. Aup1-mediated regulation of Rtg3 during mitophagy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35885–35895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanki T, Klionsky DJ. Atg32 is a tag for mitochondria degradation in yeast. Autophagy. 2009;5:1201–1202. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanki T, et al. A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4730–4738. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev Cell. 2009;17:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:265–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meeusen SL, Nunnari J. How mitochondria fuse. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Twig G, et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valente EM, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304:1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin SM, et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:933–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narendra DP, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarou M, et al. PINK1 drives Parkin self-association and HECT-like E3 activity upstream of mitochondrial binding. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:163–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka A, et al. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1367–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank M, et al. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:2297–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dengjel J, Kristensen AR, Andersen JS. Ordered bulk degradation via autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:1057–1059. doi: 10.4161/auto.6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanki T, Wang K, Klionsky DJ. A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in mitophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6 doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.10901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bleazard W, et al. The dynamin-related GTPase Dnm1 regulates mitochondrial fission in yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:298–304. doi: 10.1038/13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otsuga D, et al. The dynamin-related GTPase, Dnm1p, controls mitochondrial morphology in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:333–349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomes LC, Di Benedetto G, Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:589–598. doi: 10.1038/ncb2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sesaki H, Southard SM, Yaffe MP, Jensen RE. Mgm1p, a dynamin-related GTPase, is essential for fusion of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2342–2356. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong ED, et al. The dynamin-related GTPase, Mgm1p, is an intermembrane space protein required for maintenance of fusion competent mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:341–352. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong ED, et al. The intramitochondrial dynamin-related GTPase, Mgm1p, is a component of a protein complex that mediates mitochondrial fusion. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:303–311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeshige K, Baba M, Tsuboi S, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Autophagy in yeast demonstrated with proteinase-deficient mutants and conditions for its induction. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:301–311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanki T, Wang K, Cao Y, Baba M, Klionsky DJ. Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev Cell. 2009;17:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abeliovich H. Stationary-phase mitophagy in respiring Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2003–2011. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornmann B, et al. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science. 2009;325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornmann B, Walter P. ERMES-mediated ER-mitochondria contacts: molecular hubs for the regulation of mitochondrial biology. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1389–1393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murley A, et al. ER-associated mitochondrial division links the distribution of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in yeast. Elife. 2013;2:e00422. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman JR, et al. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bateman JM, Iacovino M, Perlman PS, Butow RA. Mitochondrial DNA instability mutants of the bifunctional protein Ilv5p have altered organization in mitochondria and are targeted for degradation by Hsp78 and the Pim1p protease. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47946–47953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klinger H, et al. Quantitation of (a)symmetric inheritance of functional and of oxidatively damaged mitochondrial aconitase in the cell division of old yeast mother cells. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mao K, Wang K, Liu X, Klionsky DJ. The scaffold protein atg11 recruits fission machinery to drive selective mitochondria degradation by autophagy. Dev Cell. 2013;26:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuspiel M, et al. Cargo-selected transport from the mitochondria to peroxisomes is mediated by vesicular carriers. Curr Biol. 2008;18:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soubannier V, et al. A vesicular transport pathway shuttles cargo from mitochondria to lysosomes. Curr Biol. 2012;22:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soubannier V, Rippstein P, Kaufman BA, Shoubridge EA, McBride HM. Reconstitution of mitochondria derived vesicle formation demonstrates selective enrichment of oxidized cargo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincow ES, et al. The PINK1-Parkin pathway promotes both mitophagy and selective respiratory chain turnover in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6400–6405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221132110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim TY, et al. Metabolic labeling reveals proteome dynamics of mouse mitochondria. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:1586–1594. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.021162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abeliovich H, Zhang C, Dunn WAJ, Shokat KM, Klionsky DJ. Chemical genetic analysis of Apg1 reveals a non-kinase role in the induction of autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:477–490. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell RE, et al. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westermann B, Neupert W. Mitochondria-targeted green fluorescent proteins: convenient tools for the study of organelle biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2000;16:1421–1427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200011)16:15<1421::AID-YEA624>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abeliovich H, Darsow T, Emr SD. Cytoplasm to vacuole trafficking of aminopeptidase I requires a t-SNARE-Sec1p complex composed of Tlg2p and Vps45p. EMBO J. 1999;18:6005–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolte S, Cordelieres FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rigbolt KT, Vanselow JT, Blagoev B. GProX, a user-friendly platform for bioinformatics analysis and visualization of quantitative proteomics data. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:O110.007450. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O110.007450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desiere F, et al. The PeptideAtlas project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D655–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.