Abstract

This report describes two non-cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis who underwent successful balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) of gastric varices with a satisfactory response and no complications. One patient was a 35-year-old female with a history of Crohn's disease, status post-total abdominal colectomy, and portal vein and mesenteric vein thrombosis. The other patient was a 51-year-old female with necrotizing pancreatitis, portal vein thrombosis, and gastric varices. The BRTO procedure was a useful treatment for gastric varices in non-cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis in the presence of a gastrorenal shunt.

Keywords: Balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration, Portal hypertension, Hemorrhage, Embolization

INTRODUCTION

Balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) of gastric varices is a procedure used to manage cirrhotic patients with isolated gastric variceal bleeding (1, 2). Portal vein thrombosis can be a cause of isolated gastric varices in non-cirrhotic patients such as those with Crohn's disease or chronic pancreatitis. No reports are available on the BRTO procedure in patients with gastric varices and concomitant portal vein thrombosis (either with or without cirrhosis). We describe two non-cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis, complicated by gastric varices that underwent a successful BRTO procedure with satisfactory results.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

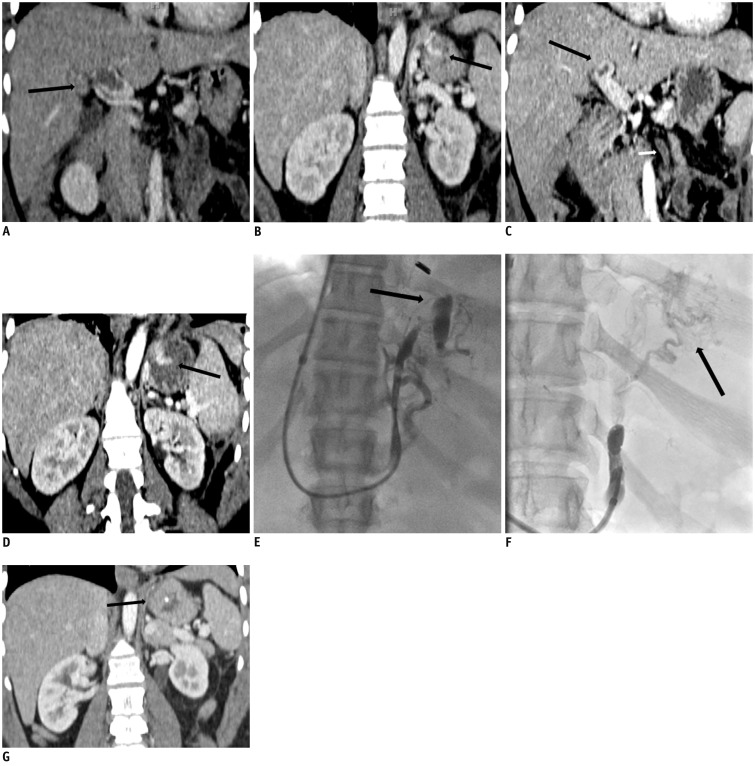

The patient was a 35-year-old woman with history of Crohn's disease and a history of portal vein thrombosis and splenic infarction 5 years ago. She underwent a total abdominal colectomy and was admitted for persistent left upper quadrant pain 10 days after surgery. An abdominal-pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan 10 days after surgery showed interval development of main portal vein thrombosis with extension into both the right and left portal veins (Fig. 1A) and small isolated varices in the gastric fundus (Fig. 1B). She was discharged with Coumadin and Lovenox after control of pain. She was readmitted 2 weeks later for increasing left upper quadrant pain. The 2 week follow-up abdominal-pelvis CT scan showed an interval decrease in the size of the portal vein thrombosis but a new inferior mesenteric vein thrombosis (Fig. 1C) and an interval increase in the size of the gastric varices (Fig. 1D). The patient did not have any symptoms of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding at admission.

Fig. 1.

35-year-old women with history of Crohn's disease, status post total abdominal colectomy, and portal vein and mesenteric vein thrombosis.

A, B. Coronal reformatted contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan 2 weeks after surgery shows large filling defect (arrow) in main portal vein with extension into both right and left portal veins and small isolated varices (arrow) in gastric fundus. C, D. Coronal reformatted contrast-enhanced CT scan at 2 week follow up shows interval decrease in size of portal vein thrombosis, new inferior mesenteric vein thrombosis (small arrow), and interval increase in size of gastric varices (arrow). E. Balloon occluded retrograde venogram shows filling of small gastric varices (arrow). Sclerosant was administered with filling of varices and occlusion balloon inflated. F. Spot image after embolization shows gastric varices with lipiodol uptake (arrow). G. Coronal reformatted contrast-enhanced CT scan 3 months after balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration procedure shows complete obliteration of gastric fundus with small residual lipiodol uptake (arrow).

Due to the portal and inferior mesenteric vein thrombosis, she was planned to continue on anticoagulation with Coumadin therapy. However, due to the presence of gastric varices, a significant risk of variceal bleeding existed with anticoagulation medication. Additionally, an interval increase in the size of the gastric varices was observed on the CT scan compared with previous scans. The primary care team wanted to treat these gastric varices with a minimally invasive procedure such as BRTO, although the size of the gastric varices was relatively small. Therefore, she was referred for the BRTO procedure for prophylactic embolization of the gastric varices considering the presence of a gastrorenal shunt. Laboratory data before the BRTO procedure was creatinine, 0.65 mg/dL; bilirubin, 0.1 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase (AST), 10 units/L; alanine transaminase (ALT), 7 units/L; albumin, 2.7 g/dL; and PT/INR, 18.5 sec/1.51.

The procedure was performed under moderate sedation with intravenous midazolam hydrochloride and fentanyl citrate. We initially accessed the right internal jugular vein and placed a 9 Fr sheath. An 8 Fr renal double curve guiding catheter (Vista Britetip IG; Cordis, Miami, FL, USA) was placed in the left renal vein. Then, a 6 Fr balloon wedge pressure catheter (Teleflex Medical, Arrow International Inc., Reading, PA, USA) was placed in the gastrorenal shunt, and balloon occluded retrograde venography was performed. A venogram showed filling of the small gastric varices (Fig. 1E). The sclerosant was administered with the occlusion balloon inflated, and the varices were filled under fluoroscopic guidance over 30 minutes. We used 4 mL of 3% sodium tetradecol sulfate as the sclerosant (Sotradecol; AngioDynamics, Queensbury, NY, USA) mixed with 2 mL lipiodol (Ethiodol; Savage Laboratories, Melville, NY, USA) and 6 mL of air. The spot image after embolization showed shrunken gastric varices with lipiodol uptake (Fig. 1F). The balloon occlusion catheter was left in place for 30 minutes. Then, no residual gastric varix was observed after some reflux of sclerosant agent into the coronary vein, and no retrograde flow into the renal vein was observed after deflating the occlusion balloon. Thus, we decided to remove the occlusion catheter and sheath.

The patient was started on anticoagulation treatment and was discharged home on Coumadin. The post-procedural course was uneventful with no evidence of upper GI bleeding. A follow-up upper endoscopy at 105 days post procedure showed complete resolution of the gastric varices. Follow up CT scans at 3 and 5 months post BRTO procedure showed complete resolution of the portal vein thrombosis and complete obliteration of the gastric varices (Fig. 1G).

Case 2

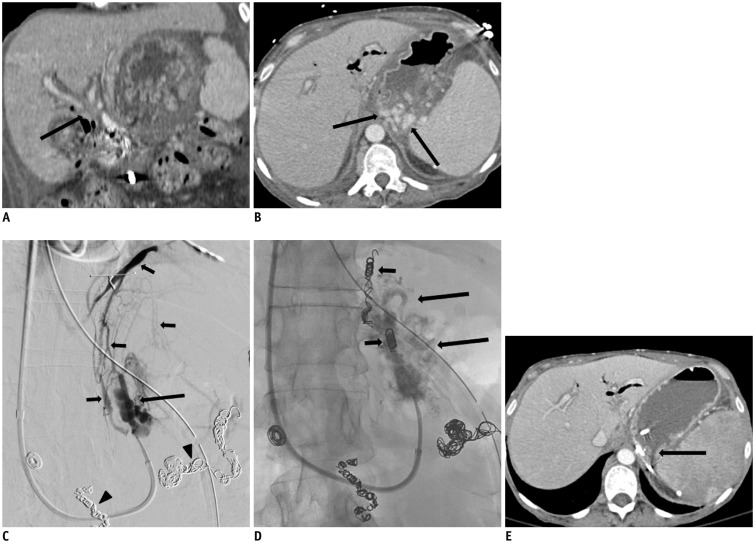

The patient was a 51-year-old woman with necrotizing pancreatitis and extensive enterocutaneous fistulas also complicated by portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation and splenic vein thrombosis (Fig. 2A). She also had multiple episodes of upper GI bleeding for which she had undergone an upper GI endoscopy and ligation of the varices. She underwent splenic artery and gastroduodenal artery embolization due to recurrence of the upper GI bleeding. She was referred for a BRTO procedure due to continual upper GI bleeding even after multiple variceal ligations, splenic and gastroduodenal artery embolization, and persistence of multiple gastric varices on both upper GI endoscopy and CT imaging (Fig. 2B). Laboratory data before the BRTO procedure was creatinine, 0.6 mg/dL; bilirubin, 4.4 mg/dL; AST, 92 units/L; ALT, 59 units/L; albumin, 2.2 g/dL; and PT/INR, 19.1 sec/1.58.

Fig. 2.

51-year-old women with necrotizing pancreatitis, portal vein thrombosis, and gastric varices.

A, B. Coronal reformatted (A) and axial (B) contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan 3 days prior to balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) procedure shows abrupt cut off of both right and left portal veins (arrow), representing portal vein thrombus, splenic vein thrombosis, and enhancing dilated veins (arrows) in region of gastric fundus representing gastric varices. C. Balloon occluded retrograde venogram shows filling of gastric varices (arrow) and multiple collateral veins including inferior phrenic vein (small arrows). Note previous coil embolized splenic and gastroduodenal arteries (arrowheads). Two collateral veins including inferior phrenic vein were embolized with multiple microcoils. Sclerosant was administered with occlusion balloon inflated and filling of varices. D. Spot image of gastric varices post embolization shows gastric varices with lipiodol uptake (arrows) and multiple coils (small arrows) at embolized inferior phrenic vein and small draining vein. E. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan 6 months after BRTO procedure shows complete obliteration of gastric fundus with small residual lipiodol uptake (arrow).

The same BRTO technique that was described for the first case was used. A balloon occluded retrograde venogram showed filling of the gastric varices and multiple collateral veins including the inferior phrenic vein (Fig. 2C). Two collateral veins including the inferior phrenic vein were catheterized with a 2.7 Fr microcatheter (Progreat; Terumo Medical, Elkton, MD, USA) and embolized with multiple 6 mm and 4 mm microcoils (Nester coil; Cook Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA). A Gelfoam slurry was used to embolize multiple small collateral veins before administering the sclerosant. The sclerosant was administered with the occlusion balloon inflated, and the varices were filled under fluoroscopic guidance over 40 minutes. Six mL of 3% sodium tetradecol sulfate was used as the sclerosant (Sotradecol; AngioDynamics) mixed with 3 mL lipiodol (Ethiodol; Savage Laboratories) and 9 mL of air. A spot image after embolization showed shrunken gastric varices with lipiodol uptake (Fig. 2D). The balloon occlusion catheter was left in place overnight through the guiding catheter. The patient was monitored in the intensive care unit to assess the therapeutic response as well as delayed complications. A complete blood count and hepatic function panel were obtained to assess the therapeutic response the following morning. The sheath and catheters were removed the following morning after checking lipiodol uptake on plain abdominal radiography.

The patient's upper GI bleeding cleared within a few days after the procedure, and she was discharged. Follow-up upper endoscopy 65 days post procedure showed normal gastric mucosa. Additionally, follow-up CT scans at 6 months post BRTO procedure showed complete obliteration of gastric varices (Fig. 2E). However due to underlying necrotizing pancreatitis with multiple enterocutaneous fistulas and abdominal wounds, she expired 8 months post procedure due to complicated sepsis.

DISCUSSION

Isolated portal vein thrombosis in the absence of underlying cirrhosis causes sinistral portal hypertension and back pressure in the left portal system (3). This pressure increase in the left portal system triggers blood drainage through two portosystemic collateral systems: the gastroesophageal and gastrophrenic venous systems. Gastroesophageal venous drainage consists of gastric varices that drain into the gastroesophageal/paraesophageal vein and ultimately into the superior vena cava (4).

Portal vein thrombosis is a rare but serious complication of Crohn's disease, mostly seen during the post-operative period following proctocolectomy (5). Our patient had a history of portal vein thrombosis and a splenic infarction 5 years ago, and this was a recurrent episode of portal vein thrombosis after a total abdominal colectomy. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in the setting of portal vein thrombosis is a very uncommon entity, and we found only one prior case report (6).

Splanchnic venous thrombosis is a relatively common finding in patients with severe pancreatitis and is seen in up to 20% of cases (7), but can cause portal hypertension in a smaller subset (9%) of them (8). However, portal vein thrombosis associated with cavernous transformation is a much less common entity and is seen in < 3% of patients (8). The presence of portal vein thrombosis and hypertension related to pancreatitis can also lead to gastric varices and bleeding (9).

Gastric varices related to portal hypertension in decompensated cirrhotic patients are traditionally treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). BRTO has been introduced as an alternate to manage gastric variceal bleeding in patients with known liver cirrhosis (1, 2). A recent study has compared the clinical outcomes of these two procedures for managing gastric varices (1). It is generally accepted that BRTO is an acceptable alternative when TIPS is contraindicated (1, 2). Patients with poor hepatic function, baseline encephalopathy, prior failed TIPS procedure, or active gastric variceal bleeding with intractable coagulopathy are situations where BRTO is the preferred procedure.

Balloon occlusion retrograde transvenous obliteration has not been described in patients with gastric varices and portal vein thrombosis. A portal vein thrombosis is not a contraindication for the TIPS procedure, and there are acceptable success rates in the literature (10). However, due to technical difficulties, portal vein thrombosis is considered a relative contraindication for creating a TIPS (11). Thus, management of gastric variceal bleeding in decompensated cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis is mostly dependent on the skill level of the operator. BRTO might be an acceptable alternative for managing gastric varices in patients with portal vein thrombosis in the presence of a gastrorenal shunt.

Intraportal thrombolysis with/without mechanical thrombectomy from TIPS could be useful treatment for symptomatic portal vein thrombosis (12-14). However, there is a risk of bleeding from the transhepatic approach and creating a TIPS in non-cirrhotic patients remains controversial. In case 1, transhepatic portal vein thrombolysis with/without mechanical thrombectomy and gastric variceal embolization could be a good alternative. However, there was a decrease in size of the portal vein thrombosis from systemic anticoagulation and there was a risk of bleeding from the transhepatic approach. Thus, we decided to perform the BRTO procedure for the gastric varices. In case 2, chronic thrombosis of main portal vein, splenic vein, and mesenteric vein with cavernous transformation was observed. Therefore, TIPS could be more difficult than the BRTO procedure.

We previously left the balloon inflated for > 4 hours or overnight according to the timing of the procedure. However, in case 1, there was no residual gastric varix 30 minutes after balloon inflation, with some reflux of sclerosant agent into the coronary vein and no retrograde flow into the renal vein after deflation of the balloon. Thus, we decided to remove the occlusion catheter and sheath.

In conclusion, portal vein thrombosis can be a cause of isolated gastric varices in non-cirrhotic patients such as those with Crohn's disease or chronic pancreatitis. If there is a gastrorenal shunt, the BRTO procedure can be a useful treatment for gastric varices in non-cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis.

Footnotes

This paper was presented as a scientific poster (p462) at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe European Congress of Radiology, Munich, Germany.

References

- 1.Saad WE, Darcy MD. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) versus Balloon-occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO) for the Management of Gastric Varices. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:339–349. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi YH, Yoon CJ, Park JH, Chung JW, Kwon JW, Choi GM. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric variceal bleeding: its feasibility compared with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Korean J Radiol. 2003;4:109–116. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2003.4.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson RJ, Taylor MA, McKie LD, Diamond T. Sinistral portal hypertension. Ulster Med J. 2006;75:175–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiyosue H, Ibukuro K, Maruno M, Tanoue S, Hongo N, Mori H. Multidetector CT anatomy of drainage routes of gastric varices: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2013;33:87–100. doi: 10.1148/rg.331125037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Oncel M, Baker ME, Church JM, Ooi BS, et al. Portal vein thrombi after restorative proctocolectomy. Surgery. 2002;132:655–661. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127689. discussion 661-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yada S, Hizawa K, Aoyagi K, Hashizume M, Matsumoto T, Koga H, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy due to chronic portal vein occlusion in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1376–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.424_e.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzelez HJ, Sahay SJ, Samadi B, Davidson BR, Rahman SH. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in severe acute pancreatitis: a 2-year, single-institution experience. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:860–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bockhorn M, Gebauer F, Bogoevski D, Molmenti E, Cataldegirmen G, Vashist YK, et al. Chronic pancreatitis complicated by cavernous transformation of the portal vein: contraindication to surgery? Surgery. 2011;149:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin YL, Yang PM, Huang GT, Lee TH, Chau SH, Tsang YM, et al. Variceal bleeding due to segmental portal hypertension caused by chronic pancreatitis. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:676–677. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han G, Qi X, He C, Yin Z, Wang J, Xia J, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis with symptomatic portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perarnau JM, Baju A, D'alteroche L, Viguier J, Ayoub J. Feasibility and long-term evolution of TIPS in cirrhotic patients with portal thrombosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1093–1098. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328338d995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilbao JI, Elorz M, Vivas I, Martínez-Cuesta A, Bastarrika G, Benito A. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the treatment of venous symptomatic chronic portal thrombosis in non-cirrhotic patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:474–480. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0241-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo J, Yan Z, Wang J, Liu Q, Qu X. Endovascular treatment for nonacute symptomatic portal venous thrombosis through intrahepatic portosystemic shunt approach. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollingshead M, Burke CT, Mauro MA, Weeks SM, Dixon RG, Jaques PF. Transcatheter thrombolytic therapy for acute mesenteric and portal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:651–661. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000156265.79960.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]