Abstract

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) is elevated during several neurologic conditions that involve cerebral edema formation, including severe preeclampsia and eclampsia; however, our understanding of its effect on the cerebral vasculature is limited. We hypothesized that oxLDL induced blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption and changes in cerebrovascular reactivity occurs through NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide. We also investigated the effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced changes in the cerebral vasculature as this is commonly used in preventing cerebral edema formation. Posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) from female rats were perfused with 5μg/mL oxLDL in rat serum with or without 50μM apocynin or 16mM MgSO4 and BBB permeability and vascular reactivity were compared. oxLDL increased BBB permeability and decreased myogenic tone that were prevented by apocynin. oxLDL increased constriction to the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NNA that was unaffected by apocynin. oxLDL enhanced dilation to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside that was prevented by apocynin. MgSO4 prevented oxLDL-induced BBB permeability without affecting oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic tone. Thus, oxLDL appears to cause BBB disruption and vascular tone dysregulation through NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide. These results highlight oxLDL and NADPH oxidase as potentially important therapeutic targets in neurologic conditions that involve elevated oxLDL.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier permeability, oxidized LDL, magnesium sulfate, cerebral arteries, myogenic responses

Introduction

It has become recognized that oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) is one of the key factors in the pathogenesis of many cardiovascular diseases.1 Oxidative modification of physiological native LDL (nLDL) into oxLDL occurs in numerous disease states as a result of oxidative stress and the presence of reactive oxygen species.2 The formation of oxLDL initiates multiple pathways in both endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, mostly through binding to its receptor lectin-like oxLDL receptor (LOX-1).3 oxLDL binding to LOX-1 generates complex signaling cascades leading to induction of the inflammatory pathway and increased production of superoxide that can further promote vascular dysfunction.1–3 Although less understood than in peripheral or cardiovascular disease, oxLDL also appears to contribute to cerebrovascular disease and stroke. Previous studies showed a significant association between increased circulating levels of oxLDL and cerebral ischemic lesions in stroke patients that may be related to the presence of oxidative stress.4, 5 In addition, high doses of oxLDL increases BBB permeability in cultured cerebral endothelial cells6 and in isolated cerebral arteries that was prevented by LOX-1 inhibition and scavenging peroxynitrite.7 Thus, oxLDL may be an important therapeutic target for cerebrovascular disease and stroke, especially under conditions of oxidative stress and cerebral edema formation.

Oxidative and nitrosative stress are known to have detrimental effects on cerebrovascular reactivity and BBB permeability, however, the role of oxLDL in these events is largely unknown. oxLDL activates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase to produce superoxide and may have an important role in cerebrovascular dysregulation.8, 9 Superoxide and peroxynitrite are known to affect vascular tone and myogenic reactivity that are important for control of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebrovascular resistance (CVR).10–12 In addition, increased BBB permeability caused by oxLDL may also promote vasogenic edema formation and contribute to life-threatening neurologic symptoms associated with conditions such as ischemic stroke, seizure, and severe preeclampsia. In fact, our previous study showed that increased circulating levels of oxLDL in severe preeclamptic women induced BBB disruption that was prevented by scavenging peroxynitrite.13 However, the mechanism by which oxLDL causes peroxynitrite generation to induce BBB disruption is not known but may be important to understand since cerebral edema is thought to be a primary mechanism by which seizure can occur during preeclampsia.10 In addition, data concerning the effect of oxLDL on cerebrovascular reactivity and myogenic responses are limited, however, potentially important in neurologic symptoms in preeclampsia where impaired cerebral autoregulation is an important contributor to formation of cerebral edema and neurologic complications.10 In the present study, we hypothesize that oxLDL to the level of women with severe preeclampsia would decrease myogenic tone and reactivity of cerebral arteries that could contribute to vascular dysfunction and the formation of cerebral edema. We further hypothesized that NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide is involved in oxLDL-induced changes in the cerebral vasculature.

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) has been shown to be protective of the BBB and prevent cerebral edema during numerous conditions including traumatic brain injury, septic encephalopathy, hypoglycemia, and preeclampsia.14–16 In fact, MgSO4 is one of the primary treatments for prevention of vasogenic brain edema in severe preeclampsia.15, 16 However, if MgSO4 is also specifically protective of oxLDL-induced BBB permeability or vascular tone dysregulation remains unknown. Thus, our last aim was to investigate the effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced BBB permeability and cerebral vascular dysfunction.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female virgin nonpregnant Sprague Dawley rats (12–14 weeks; 250–300 grams) were used for all experiments. The animals were purchased from Charles River (Saint-Constant, QB, Canada) and housed until experimentation at the University of Vermont Animal Care Facility, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility. Animals had access to food and water ad libitum and maintained a 12-hour light/dark cycle.

Rat serum samples

Serum samples were obtained from trunk blood from female Sprague Dawley rats and collected in serum separator tubes. After a waiting period of 30 minutes, the tubes were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2500 revolutions per minute, and the serum pooled from ~10 animals and aliquoted. The pooled serum was then stored at -80 ºC until experimentation. For each experiment, one aliquot of pooled serum was used.

BBB permeability studies

To investigate the effect of oxLDL on BBB permeability and determine the mechanism by which oxLDL increases permeability, hydraulic conductivity (Lp), the critical transport parameter that relates water flux to hydrostatic pressure, was measured in isolated PCAs from female nonpregnant rats, as described previously.17 This method of measuring BBB permeability has been successfully used in several previous studies.17–19 Briefly, a third-order branch of the PCA was carefully dissected out of the brain and the proximal end mounted on a glass microcannula in an arteriograph chamber. PCAs were perfused intraluminally with 20% v/v serum from female rats with (n=8) or without (n=8) the presence of 5 μg/ml oxLDL or 5 μg/ml native LDL (nLDL; n=4) in HEPES buffer for 1 hour at 75.0 ± 0.3 mmHg and 37.0 ºC ± 0.2 ºC. The concentration of oxLDL used for these experiments was based on a previous study that determined the concentration of oxLDL in plasma of severe preeclamptic women to be approximately 5 μg/ml.13 To determine the involvement of NADPH oxidase activity in oxLDL-induced BBB permeability, a separate set of PCAs were perfused with 50 μM of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (n=8) in addition to the oxLDL-serum mixture. To determine the effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced BBB permeability, another set of PCAs was perfused with 16 mM MgSO4 in addition to the oxLDL-serum mixture. This dose of MgSO4 was chosen because it is within the therapautic range for MgSO4 for seizure profylaxis.16, 20 After the equilibration period, intravascular pressure was increased to 80.0 mmHg ± 0.1 mmHg and the drop in pressure due to transvascular filtration across the vascular wall in response to hydrostatic pressure was measured for 40 minutes. The decrease in intravascular pressure per minute (mmHg/min) was converted to volume flux across the vessel wall (3m3) using a conversion curve, as previously described.17 Lp was then determined by normalizing flux to surface area and oncotic pressure of the serum perfusate.

Reactivity studies

Another set of experiments was performed to determine the effect of oxLDL on reactivity of PCAs. A third-order branch of the PCA was carefully dissected from the brain of female rats and and the proximal end mounted on one glass cannula in an arteriograph chamber. PCAs were perfused intraluminally with 20% v/v serum from female rats with (n=8) or without (n=8) the presence of 5 μg/ml oxLDL or 5 μg/ml nLDL (n=4) in a HEPES buffer for 2 hours at 80.0 ± 0.3 mmHg and 37.0 ºC ± 0.2 ºC. The distal end of the vessel was tied off to avoid flow-mediated responses. The proximal cannula of the arteriograph was connected to a pressure transducer and servo controller that maintained intravascular pressure at a set pressure or changed manually. Lumen diameter of the PCA was measured via video microscopy during the experiment. After the equilibration period, intravascular pressure was increased in steps of 20 mmHg to 140 mmHg and lumen diameter was recorded at each pressure once stable. Pressure was then returned to 80 mmHg for the remainder of the experiment. A single concentration (0.1 mmol/L) of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA) was added to the bath and constriction in response to NOS inhibition was measured after approximately 20 minutes. In the presence of L-NNA, the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was cumulatively added to the bath (10−8 M-10−5 M) and the dilation to SNP was measured at each concentration. Finally, zero-Ca2+ HEPES was added to the bath to obtain fully relaxed diameters. Passive diameters were then recorded at pressures from 140 to 5 mmHg.

Data Calculations

Percent tone was calculated as the percent decrease in diameter from the fully relaxed diameter in zero-Ca2+ HEPES by the equation: ((Ø passive- Øactive)/ Øpassive) × 100%, where Øpassive is the diameter in zero- Ca2+ HEPES and Øactive is the diameter when the vessels had tone. Percent constriction to L-NNA was calculated with the equation: ((Øbaseline-Ødrug)/ Øbaseline) × 100% where Øbaseline is diameter before adding the L-NNA and Ødrug is diameter with presence of L-NNA. Percent sensitivity to the NO donor SNP using a concentration-response curve was calculated with the equation: ((Ødrug-Øminimum)/( Ømaximum – Øminimum)) × 100% where Ødrug is diameter at a specific concentration of SNP, Øminimum is diameter at the lowest concentration of SNP and Ømaximum is the diameter at the highest concentration of SNP. The effective concentration that produced half maximal dilation to SNP (EC50) was calculated from individual plots of each curve and averaged.

Drugs and solutions

HEPES physiological salt solution was made fresh daily and consisted of (mmol/L): 142.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.71 MgSO4, 0.50 EDTA, 2.8 CaCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 1.2 KH2PO4, and 5.0 dextrose. HEPES without Ca2+ was also made daily but Ca2+ was left out of the solution. Apocynin, L-NNA and SNP were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). The concentrated apocynin was diluted in double distilled H2O to reach the concentration of 50 μM and was stored in −20 ºC until used. L-NNA and SNP were made as stock solutions and diluted. Highly oxLDL was purchased from Kalen Biomedical (LLC, Montgomerey Village, Mn, USA; 770252-7) and stored at 4 ºC until experimentation.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post hoc Student-Newman Keuls test for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant when P< 0.05.

Results

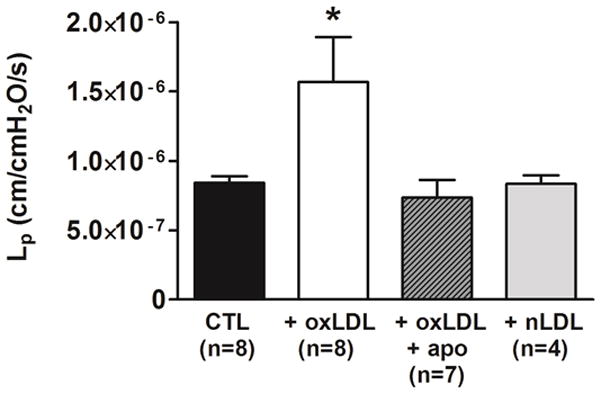

oxLDL increased BBB permeability that was prevented by apocynin

Figure 1 shows BBB permeability of PCAs in response to oxLDL. oxLDL significantly increased BBB permeability in PCAs compared to controls without oxLDL (P< 0.05). Importantly, the presence of apocynin abolished the oxLDL-induced BBB permeability (P< 0.05), suggesting that increased NADPH oxidase activity was involved in oxLDL-induced BBB disruption. To confirm that BBB permeability was increased due to the oxidative state of LDL, the effect of nLDL on BBB permeability was compared to oxLDL-induced BBB permeability. nLDL did not increase BBB permeability compared to controls, demonstrating that the increased BBB permeability was a result of the oxidative modification of LDL.

Figure 1. Effect of apocynin on oxLDL-induced BBB permeability.

Graph showing hydraulic conductivity (Lp) as a measure of BBB permeability in response to perfusion of 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to rat serum containing 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) and with 50 μM apocynin (oxLDL+apo). oxLDL significantly increased BBB permeability in PCAs from female rats compared to controls. The addition of apocynin significantly abolished the oxLDL-induced BBB permeability. Native LDL (nLDL) did not change BBB permeability compared to controls. (* P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

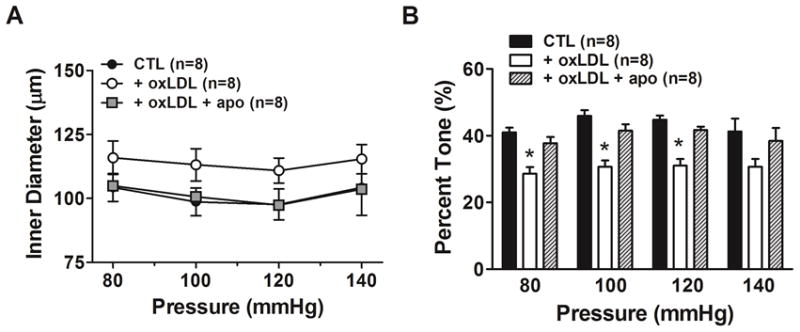

oxLDL decreased myogenic tone of PCAs that was prevented by apocynin

Figure 2A shows active diameter changes in response to increased intravascular pressure. All groups had modest constriction in response to increased pressure, demonstrating myogenic reactivity was present in all vessels. PCAs perfused with oxLDL had larger diameters at all pressures measured, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.17). However, Figure 2B shows that oxLDL significantly decreased myogenic tone compared to the control group (P< 0.05), suggesting that the larger diameters were due to diminished basal tone. Importantly, apocynin prevented the oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone in PCAs (P < 0.05). Also for these experiments, measurements were repeated with the presence of nLDL instead of oxLDL. nLDL did not cause any changes in myogenic responses or myogenic tone compared to the control group without oxLDL (data not shown), suggesting that the effects were due to the oxidative state of LDL.

Figure 2. Effect of apocynin on oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic reactivity and tone of posterior cerebral arteries.

Graphs showing (A) active lumen diameter and (B) percent myogenic tone in response to increased intravascular pressure in posterior cerebral arteries from female rats that were perfused with 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to serum containing 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) or with 50 μM apocynin (oxLDL + apo) . oxLDL caused larger lumen diameters compared to CTL at all pressures that was prevented by apocynin. oxLDL significantly decreased percent myogenic tone of PCA compared to CTL without oxLDL. The effect of oxLDL on basal tone was prevented by apocynin. (* P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

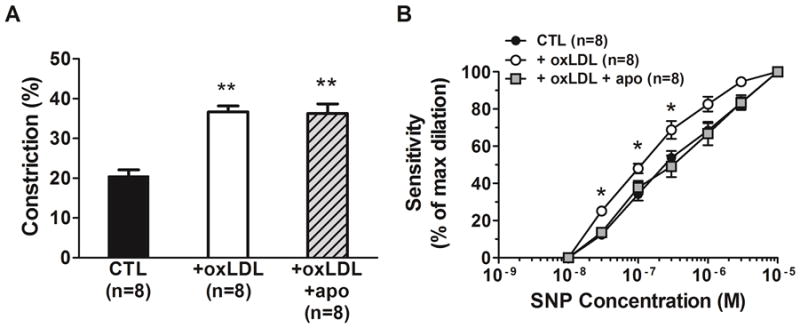

oxLDL increased contriction to NOS inhibition and enhanced NO-mediated vasodilation

To determine the effect of oxLDL on basal endothelium-derived NO, a single high concentration of L-NNA was added to PCA from all 3 groups and changes in diameter measured (Figure 3A). All vessels constricted in response to L-NNA, suggesting basal NO was present and inhibited tone. The presence of oxLDL caused a significant increase in constriction to L-NNA compared to the controls (P< 0.01). However, there was no effect of apocynin on the increased constriction to NOS inhibition induced by oxLDL. Figure 3B shows the effect of circulating oxLDL on dilation to SNP in PCA. oxLDL caused PCAs to have increased sensitivity to SNP compared to the control group that was abolished by the presence of apocynin ( P< 0.05). The EC50 values for SNP were 1.9 ± 0.2 ×10−7 M in the oxLDL group compared to 5.0 ± 0.7 ×10−7 M in the control group and 4.0 ± 0.6 ×10−7 M in the apocynin group (P< 0.05).

Figure 3. Effect of apocynin on oxLDL-induced changes in constriction to NOS inhibition and dilation to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in posterior cerebral arteries.

Graphs showing (A) constriction to NOS inhibition with L-NNA and (B) sensitivity to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in posterior cerebral arteries from female rats that were perfused with 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to rat serum plus 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) and with 50 μM apocynin (oxLDL+apo). Perfusion of oxLDL caused a significant increase in constriction to L-NNA in PCA compared to CTL. Apocynin did not affect the oxLDL-induced increase in contriction to L-NNA. oxLDL significantly increased sensitivity to SNP in PCA that was abolished by apocynin. (** P< 0.01 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA;* P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

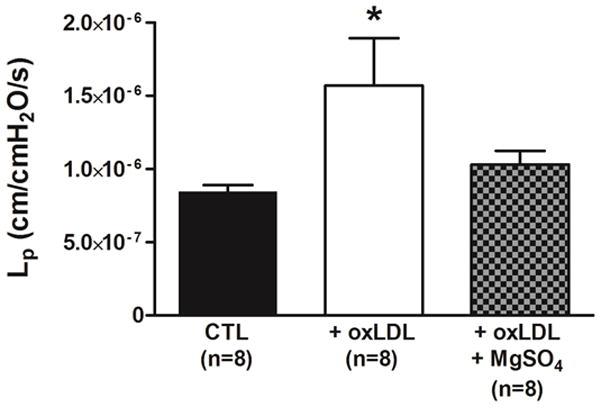

MgSO4 prevented oxLDL-induced BBB permeability

Figure 4 shows the effect of MgSO4 on BBB permeability induced by oxLDL. MgSO4 prevented the oxLDL-induced BBB permeability (P< 0.05) that was similar to controls, suggesting a direct protective effect on oxLDL-induced BBB permeability.

Figure 4. Effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced BBB permeability.

Graph showing hydraulic conductivity (Lp) as a measure of BBB permeability in response to perfusion of 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to serum plus 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) and with 16 mM MgSO4 (oxLDL+ MgSO4). oxLDL caused an increase in BBB permeability that was prevented by MgSO4. (*P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

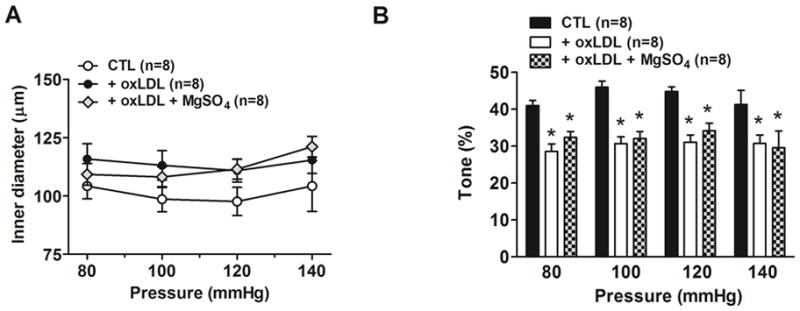

MgSO4 did not affect oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone

The effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic reactivity and tone are shown in Figures 5A and 5B. MgSO4 did not affect the active myogenic response in the PCAs or prevented the oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone, suggesting the protective effect of MgSO4 was selective for BBB permeability.

Figure 5. Effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic tone of posterior cerebral arteries.

Graphs showing (A) active myogenic responses and (B) myogenic tone in posterior cerebral arteries in response to increased intravascular pressure after perfusion with 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to serum plus 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) and with 16 mM MgSO4 (oxLDL+MgSO4). There was no difference in lumen diameters between groups. In addition, MgSO4 did not prevent the decrease in myogenic tone induced by oxLDL. (* P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

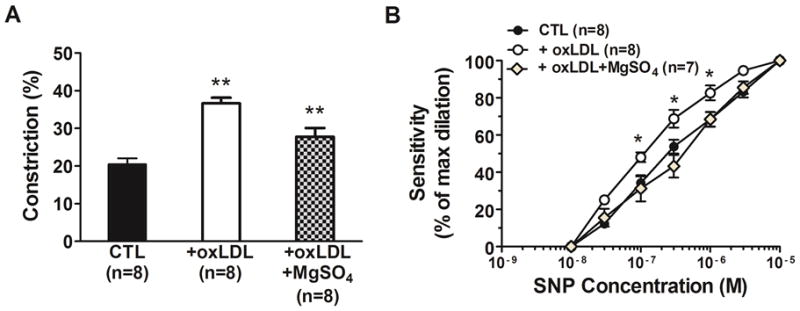

MgSO4 decreased oxLDL-induced dilation to SNP without affecting oxLDL-induced constriction to NOS inhibition

Figure 6A and 6B show the constriction to NOS inhibition and dilation to the NO-donor SNP of PCAs due to oxLDL with or without the presence of MgSO4. MgSO4 treatment did not significantly affect the constriction to L-NNA, however, it did prevent the oxLDL-induced enhanced dilation to SNP in PCAs (P< 0.05). The EC50 values for SNP were 4.9 ± 0.8 ×10−7 M in the MgSO4 group that was not different from the control group (5.0 ± 0.7 ×10−7 M) but significantly higher compared to the oxLDL group (1.9 ± 0.2 ×10−7 M; P< 0.05).

Figure 6. Effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced constriction to NOS inhibition and dilation to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in posterior cerebral arteries.

Graphs showing (A) constriction to NOS inhibition with L-NNA and (B) sensitivity to the NO donor SNP in posterior cerebral arterires in response to perfusion of 20% v/v rat serum alone (CTL) compared to serum plus 5 μg/ml oxLDL without (oxLDL) or with 16 mM MgSO4 (oxLDL+ MgSO4). The presence of MgSO4 did not significantly affect the oxLDL-induced increase in contriction to L-NNA. However, MgSO4 prevented the increased sensitivity to SNP in response to oxLDL. (** P< 0.01 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA; * P< 0.05 vs. all other groups by one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

oxLDL has become a known key factor in the pathogenesis of many cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. However, information regarding the effect or mechanism of oxLDL in the cerebral vasculature remain limited. In the present study, we determined the effect of oxLDL on BBB permeability and cerebral vascular function and investigated the mechanim by which it acts to increase permeability and diminsh myogenic tone. In addition, we examined the possible beneficial effects of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced changes in BBB permeability and cerebral vascular reactivity, as it has been shown to be beneficial in treating several neurologic conditions that are associated with elevated oxLDL, including severe preeclampsia.7,13 The results of the present study demonstrate that oxLDL, but not native LDL, significantly increased BBB permeability and decreased myogenic tone in PCAs that was associated with increased constriciton to NOS inhibition and dilation to SNP. Inhibition of NADPH-dervived superoxide with apocynin prevented much of the detrimental effects of oxLDL, including increased BBB permeability and sensitivity to SNP, but not constriction to NOS inhibition. Treatment with MgSO4 also protected the BBB and prevented oxLDL-induced BBB disruption as well, but without affecting the oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic tone. Taken together, these results suggest that oxLDL causes BBB disruption and cerebrovascular tone dysregulation through activation of NADPH oxidase whereas the effect of MgSO4 treatment on oxLDL-induced vascular dysfunction appears more limited to preventing BBB disruption.

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that increased levels of oxLDL significantly increased BBB permeability that was prevented by apocynin, suggesting the effect was mediated by NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide. We also show that this effect was specifically due to the oxidative modification of LDL, as nLDL did not affect BBB permeability. It is generally accepted that increased levels of superoxide rapidly bind NO to generate peroxynitrite, a toxic radical that causes endothelial dysfunction.21 Thus, we speculate that oxLDL increases superoxide production through NADPH oxidase that leads to subsequent generation of peroxynitrite, resulting in BBB disruption. Our proposed mechanism is supported by several previous reports using cell-culture models showing that increased levels of oxLDL generate superoxide production through NADPH oxidase, leading to increased production of peroxynitrite.8, 22 Importantly, because NADPH oxidase activity is greater in the cerebral vasculature compared to the systemic vasculature, 23 oxLDL-induced increased activity of NADPH oxidase may result in excessive production of superoxide in the cerebral vasculature leading to extensive damage of the BBB and vasogenic brain edema. Thus, oxLDL and NADPH oxidase may be important therapeutic targets for treatment and/or prevention of neurologic symptoms in preeclampsia and possibly other neurologic conditions where BBB disruption and edema formation is involved.

In the present study, we found that acute intraluminal exposure of oxLDL caused PCAs to have larger diameters and significantly decreased myogenic tone, an effect that could lead to diminished CVR, hyperperfusion, and BBB disruption due to high hydrostatic pressure.10 To our knowledge, this is the first report to show the detrimental effects of 5μg/ml oxLDL on PCA function. We used this concentration because this is what was measured in women with severe, early-onset preeclamspia.13 A previous study investigated the effect of 10 μg/ml oxLDL on PCAs from rabbits and found that oxLDL increased myogenic tone, which is in contrast to the results of the present study.24 However, the concentration used in the previous study was higher than in the present study. Previous reports have described differential effects of oxLDL on the systemic vasculature depending on the concentration such that oxLDL > 10μg/ml increased myogenic tone due to decreased NO production, while concentrations of oxLDL < 10μg/ml increased NO production and decreased myogenic tone.25, 26 The difference between these studies may also be due to species or gender differences as the previous study used PCAs from male rabbits.

The mechanism by which oxLDL caused decreased myogenic tone is not clear, however, it may be due to increased endothelium-dependent NO production as we also found oxLDL increased constriction to LNNA. However, the increased constriction to LNNA may be due either increased NO production by the endothelium or increased sensitivity of the smooth muscle to NO. Because we found the oxLDL also increased sensitivity to SNP, it is possible the decrease in tone is due to increased sensitivity to endothelium-derived NO and not to increased NO production. The effect of oxLDL on dilation to SNP has been examined in several studies. In the abdominal aorta, oxLDL did not affect the dilation to SNP.27 However, another study found that oxLDL decreased dilation to SNP in carotid arteries without affecting dilation to SNP in basilar arteries, suggesting oxLDL may affect smooth muscle function differently in different vascular beds.28 Importantly, all these previous studies used concentrations that were at least 10-fold higher in concentration than used in this study.

The present study also found that the presence of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin prevented the oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone, suggesting superoxide production may be involved in this response. In a previous study, we demonstrated that high cholesterol-treated rats had PCAs with decreased myogenic tone that was due to generation of peroxynitrite.7, 11 It is possible that oxLDL-induced superoxide production combines with NO to generate peroxynitrite that is the vasoactive component. This hypothesis is supported by previous reports that found that peroxynitrite is a powerful vasodilator at high concentrations and decreases myogenic tone in the cerebral vasculature.11, 29, 30 However, apocynin did not prevent the increase in constriction to LNNA, suggesting that only superoxide, and not NO, is involved in oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone. Further studies are needed to specifically address the underlying mechanism by which oxLDL decreases tone and the role of NO, superoxide and peroxynitrite.

In addition, we determined the effect of MgSO4 on oxLDL-induced BBB disruption and vascular tone dysregulation. MgSO4 is widely used and effective in the management of severe preeclampsia for prevention of neurologic complications such as seizures.31 Here, we found that MgSO4 abolished oxLDL-induced BBB permeability without affecting oxLDL-induced changes in myogenic tone. These results confirm earlier reports that MgSO4 is protective of the BBB without causing significant dilation in the cerebral vasculature. However, it is not clear from this study if MgSO4 directly antagonizes the mechanism of oxLDL that leads to BBB disruption or if MgSO4 had an overall protective effect on the BBB. It is possible that the mechanism by which MgSO4 acts is through its ability to scavenge free radicals such as superoxide and decrease lipid-peroxidation.32 Although this may explain the protective effect of MgSO4 on BBB disruption, oxLDL-induced decrease in myogenic tone was not prevented, suggesting MgSO4 may act primarily to protect the cerebral endothelium.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates for the first time that oxLDL causes increased BBB permeability and cerebral vascular tone dysregulation that was prevented by apocynin, suggesting involvement of NADPH oxidase derived superoxide in these oxLDL-induced effects. In addition, treatment with MgSO4 prevented oxLDL-induced BBB disruption without affecting cerebral myogenic tone. These results demonstrate the significance of oxLDL in the occurence of cerebral vascular dysfunction in conditions such as severe preeclampsia and may be an important marker in the pathogenesis of many neurologic conditions that involve cerebral edema formation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the NINDS grants RO1 NS045940 and the NINDS Neural Environment Cluster supplement RO1 NS045940-06S1. We also gratefully acknowledge the support of NHLBI grant PO1 HL095488 and the Totman Medical Research Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Li D, Mehta JL. Oxidized ldl, a critical factor in atherogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:353–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitra S, Goyal T, Mehta JL. Oxidized ldl, lox-1 and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011;25:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itabe H. Oxidative modification of ldl: Its pathological role in atherosclerosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;37:4–11. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uno M, Harada M, Takimoto O, Kitazato KT, Suzue A, Yoneda K, Morita N, Itabe H, Nagahiro S. Elevation of plasma oxidized ldl in acute stroke patients is associated with ischemic lesions depicted by dwi and predictive of infarct enlargement. Neurol Res. 2005;27:94–102. doi: 10.1179/016164105X18395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uno M, Kitazato KT, Nishi K, Itabe H, Nagahiro S. Raised plasma oxidised ldl in acute cerebral infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:312–316. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin YL, Chang HC, Chen TL, Chang JH, Chiu WT, Lin JW, Chen RM. Resveratrol protects against oxidized ldl-induced breakage of the blood-brain barrier by lessening disruption of tight junctions and apoptotic insults to mouse cerebrovascular endothelial cells. J nutrition. 2010;140:2187–2192. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreurs MP, Cipolla MJ. Pregnancy enhances the effects of hypercholesterolemia on posterior cerebral arteries. Reprod Sci. 2013;20:391–399. doi: 10.1177/1933719112459228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cominacini L, Rigoni A, Pasini AF, Garbin U, Davoli A, Campagnola M, Pastorino AM, Lo Cascio V, Sawamura T. The binding of oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-ldl) to ox-ldl receptor-1 reduces the intracellular concentration of nitric oxide in endothelial cells through an increased production of superoxide. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13750–13755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy Chowdhury SK, Sangle GV, Xie X, Stelmack GL, Halayko AJ, Shen GX. Effects of extensively oxidized low-density lipoprotein on mitochondrial function and reactive oxygen species in porcine aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E89–98. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00433.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cipolla MJ. Cerebrovascular function in pregnancy and eclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:14–24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maneen MJ, Cipolla MJ. Peroxynitrite diminishes myogenic tone in cerebral arteries: Role of nitrotyrosine and f-actin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1042–1050. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00800.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Silva TM, Brait VH, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, Miller AA. Nox2 oxidase activity accounts for the oxidative stress and vasomotor dysfunction in mouse cerebral arteries following ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreurs MP, Hubel CA, Bernstein IM, Jeyabalan A, Cipolla MJ. Increased oxidized low-density lipoprotein causes blood-brain barrier disruption in early-onset preeclampsia through lox-1. FASEB J. 2013;27:1254–1263. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-222216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esen F, Erdem T, Aktan D, Kalayci R, Cakar N, Kaya M, Telci L. Effects of magnesium administration on brain edema and blood-brain barrier breakdown after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003;15:119–125. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Euser AG, Bullinger L, Cipolla MJ. Magnesium sulphate treatment decreases blood-brain barrier permeability during acute hypertension in pregnant rats. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:254–261. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Magnesium sulfate for the treatment of eclampsia: A brief review. Stroke. 2009;40:1169–1175. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.527788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts TJ, Chapman AC, Cipolla MJ. Ppar-gamma agonist rosiglitazone reverses increased cerebral venous hydraulic conductivity during hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1347–1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00630.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreurs MP, Houston EM, May V, Cipolla MJ. The adaptation of the blood-brain barrier to vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor during pregnancy. FASEB J. 2012;26:355–362. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-191916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amburgey OA, Chapman AC, May V, Bernstein IM, Cipolla MJ. Plasma from preeclamptic women increases blood-brain barrier permeability: Role of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Hypertension. 2010;56:1003–1008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Resistance artery vasodilation to magnesium sulfate during pregnancy and the postpartum state. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1521–1525. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00994.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: The good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heeba G, Hassan MK, Khalifa M, Malinski T. Adverse balance of nitric oxide/peroxynitrite in the dysfunctional endothelium can be reversed by statins. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:391–398. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31811f3fd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller AA, Drummond GR, De Silva TM, Mast AE, Hickey H, Williams JP, Broughton BR, Sobey CG. Nadph oxidase activity is higher in cerebral versus systemic arteries of four animal species: Role of nox2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H220–225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00987.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie H, Bevan JA. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein enhances myogenic tone in the rabbit posterior cerebral artery through the release of endothelin-1. Stroke. 1999;30:2423–2429. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2423. discussion 2429–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DA, Cohen ML. Effects of oxidized low-density lipoprotein on vascular contraction and relaxation: Clinical and pharmacological implications in atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirata K, Miki N, Kuroda Y, Sakoda T, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M. Low concentration of oxidized low-density lipoprotein and lysophosphatidylcholine upregulate constitutive nitric oxide synthase mrna expression in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1995;76:958–962. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bocker JM, Miller FJ, Oltman CL, Chappell DA, Gutterman DD. Calcium-activated potassium channels mask vascular dysfunction associated with oxidized ldl exposure in rabbit aorta. Jpn Heart J. 2001;42:317–326. doi: 10.1536/jhj.42.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napoli C, Paterno R, Faraci FM, Taguchi H, Postiglione A, Heistad DD. Mildly oxidized low-density lipoprotein impairs responses of carotid but not basilar artery in rabbits. Stroke. 1997;28:2266–2271. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2266. discussion 2271–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maneen MJ, Hannah R, Vitullo L, DeLance N, Cipolla MJ. Peroxynitrite diminishes myogenic activity and is associated with decreased vascular smooth muscle f-actin in rat posterior cerebral arteries. Stroke. 2006;37:894–899. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204043.18592.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller AA, Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Reactive oxygen species in the cerebral circulation: Are they all bad? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1113–1120. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Chou D. Magnesium sulphate versus phenytoin for eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD000128. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000128.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ariza AC, Bobadilla N, Fernandez C, Munoz-Fuentes RM, Larrea F, Halhali A. Effects of magnesium sulfate on lipid peroxidation and blood pressure regulators in preeclampsia. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]