Abstract

Background/Objectives

Appropriate management of older adults includes assessment of cognition and understanding its relationship to function. The aim of this analysis was to examine the association between function measured by activities of daily living, both basic (BADL) and instrumental (IADL), and cognition assessed by MMSE scores among older African American and non-Hispanic White community-dwelling men and women.

Design

Cross-sectional study assessing associations between self-reported BADL and IADL difficulty and MMSE scores for race/sex specific groups.

Setting

Homes of community-dwelling older adults.

Participants

A random sample of 974 African American and non-Hispanic White Medicare beneficiaries age 65 years and older living in west-central Alabama, participating in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Study of Aging, but excluding those with reported diagnoses of dementia or with missing data.

Measurements

Function, based on self-reported difficulty in performing Basic and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (BADL and IADL); Cognition, using the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE); Multivariable, linear regression models were used to test the association of function and cognition by race and sex-specific groups after adjusting for covariates.

Results

MMSE scores were modestly correlated with BADL and IADL in all four race/sex-specific group with Pearson r values ranging from −0.189 for non-Hispanic white women and −0.429 for African American men. Correlations of MMSE with BADL or IADL difficulty in any of the race/sex-specific groups were no longer significant after controlling for socio-demographic factors and comorbidities.

Conclusion

MMSE was not significantly associated with functional difficulty among older African American and non-Hispanic white men and women in the Deep South after adjusting for socio-demographic factors and comorbidities, suggesting a mediating role in the relationship between cognition and function.

Keywords: function; basic and instrumental activities of daily living; cognitive screening; MMSE; race, ethnicity, sex, and gender differences

INTRODUCTION

Health care providers must assess cognition in older patients to provide realistic treatment recommendations and preventive care. Difficulties in cognition impact a patient’s ability to consent and adhere to prescribed therapies, to benefit from recommended referrals and services, to function independently and to enjoy life. Cognitive difficulty without frank dementia currently impacts an estimated 5.4 Million individuals aged 71 years or older in the US (1).

By 2050, non-European racial/ethnic minorities are estimated to represent nearly half of the US population, and about one-third of all persons living with cognitive difficulty, including dementia (2). Widely used cognitive assessment tools may not appropriately take into account educational and cultural characteristics of such a diverse population. Cognitive assessments using standard tests have biases based on education and other factors (3). Many physicians use these cognitive assessments to make important decisions about a person’s ability to carry out day to day functions including the ability to live alone safely, even though these assessments were not developed for these purposes. Evaluation of conventionally-used cognitive screening tools in minority populations is critical to understanding their value to care providers. We therefore studied racial/ethnic differences, similarities and associations between day to day function and performance on a widely used cognitive assessment test among 974 community-dwelling older African-American and non-Hispanic White subjects living in Birmingham, Alabama and the surrounding five central counties.

Cognitive and Function Measures Assessed

The Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is widely used to assess cognition in older adults (4). It provides brief assessment of several cognitive domains: orientation, attention, concentration, memory, visuo-constructional abilities, and language. The MMSE is also the measure by which decline in cognitive test performance is commonly measured (5-7). The MMSE cognitive assessment tool is still widely used by primary care physicians for cognitive assessment and screening (8).

Clinically, day to day function is most often described by the performance of Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL). BADL are required to live independently and include dressing, bathing, transferring from bed to chair, eating, toileting, walking, and getting outside. BADL difficulty causes an increased risk of future dependence carrying out these activities, higher admission rates to skilled-nursing facilities, and increased mortality (9).

Little is known regarding the association of BADL or IADL difficulty with MMSE scores in general. Race/sex-specific similarities or differences in such associations are not well characterized. The Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) found that MMSE scores did not correlate independently with self-reported Basic and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, but the WHAS focused on the most disabled women living in the community and did not include men (10). For this analysis, we hypothesized that MMSE scores would be associated with BADL and IADL performance in a broader population representative of the full continuum of function and cognition observed among older African American and non-Hispanic White community-dwelling women and men.

METHODS

Participants in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Study of Aging, a prospective, observational cohort study of community-dwelling older adults, provided data for this study. The UAB Study of Aging is a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries 65 and older living in five central Alabama counties recruited (November 1999- February 2001) from a list of Medicare beneficiaries provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), stratified by county, race, and sex. Specific rural counties were selected for their proximity to UAB and their proportions of African American and non-Hispanic White residents. Rural, African American, and male older adults were oversampled to achieve a balanced sample (50% African American, 50% male, and 51% rural). Inclusion criteria included the ability to use the telephone, set an appointment for an in-home visit with research staff, and answer initial interview questions by themselves. Study methods have been described in detail elsewhere (11-13). The protocol was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment. For this study, we limited analyses to participants with complete data for MMSE, BADLs and IADLs, and other covariates described below. Twenty-six participants with a physician diagnosis of dementia were excluded from the analyses.

Sociodemographic Assessment

Sociodemographic data included sex, participant-identified ethnicity, age, education, rural/urban dwelling based on the county of residence, marital status, number of persons residing with the participant, and income. Age was categorized as follows: 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years and older. Level of education was ascertained by determining the highest grade completed and categorizing as up to 8th grade, 9th thru 11th, completed 12th grade, and more than 12th grade. Total combined family income before taxes was reported in the following nine categories: less than $5,000; $5,000-$7,999; $8,000-$11,999; $12,000-15,999; $16,000-$19,999; $20,000-29,999; $30,000-$39,000; $40,000-$49,000; and greater than $50,000. The following question also was asked about participants’ perceived income: “All things considered, would you say your income is 1) not enough to make ends meet, 2) gives you just enough to get by on, 3) keeps you comfortable, but permits no luxuries, or 4) allows you to do more or less what you want.” For persons who did not report income (165 subjects), responses on perceived income were used to impute income categories based on the correspondence of income categories and perceived income among persons with answers to both questions. Persons were coded as low income if their income was under $8000 annually.

Function

Function was assessed (during the single in-home visit) based on the degree of self-reported difficulty in performing BADLs and IADLs (14). Basic activities assessed included dressing, bathing, transferring from bed to chair, eating, toileting, walking, and getting outside. Instrumental activities included using the telephone, managing money, preparing meals, doing light housework, shopping, and doing heavy housework. For each activity, participants were asked if they had any difficulty doing the task. If they indicated any difficulty, they were asked if this was some difficulty, a lot of difficulty or if they were unable to perform the task. A score of “0” was assigned if no difficulty was reported; a score of “1” was assigned if some difficulty was reported; “2” if a lot of difficulty was reported; and “3” if the participant reported being unable to perform the activity. The difficulty scores were summed for the individual tasks to develop BADL and IADL composite function scores. Thus, function scores for BADL ranged from 0-21 and scores for IADL ranged from 0-18, with higher scores representing worse function.

Cognition

Cognition was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). The MMSE includes items related to orientation, registration and recall, attention, and visuospatial construction; scores range from 0-30, with higher scores representing better cognition. We used the MMSE that included spelling the word “W-O-R-L-D” backwards, rather than serial sevens. We analyzed MMSE score distribution in the sample using MMSE as a continuous variable. Additionally, we conducted subgroup category analyses to compare within MMSE score category groups. This analysis was patterned after Leveille et al. (10), comparing African American women and Non-Hispanic White women participants based on sub groupings of MMSE scores. We did not adjust scores for education or African American race/ethnicity. We found that the Cronbach’s α for the MMSE was similar across all race/sex groups and by education level in this sample (α approximately = 0.6).

Health Measures

Specific diseases hypothesized to potentially impact cognition were included as a total count to describe comorbidity in our regression model along with sociodemographic variables (Table 1), patterned after Leveille et al.’s study investigating association of MMSE score and Activities of Daily Living in the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS). Medical diagnoses were considered verified if the patient was taking a medication for the condition, if a physician questionnaire was returned indicating that the participant had the condition, or if the condition was listed on a hospital discharge summary three years prior to enrollment in the study. Verified diagnoses of hypertension, arthritis and/or gout, prior transient ischemic attack (TIA)/stroke, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), diabetes, and cancer were considered as was Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), defined by having verified angina or heart attack or a self-report of bypass surgery, PTCA, or Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty. Hip fractures were self-reported. In addition, self-rated health was assessed by response to the question, “In general, how would you describe your health.” Responses ranged from excellent (coded as 1), very good, good, fair, to poor (coded as 5).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Medical Conditions of African American and non-Hispanic White Participants.

| Characteristics | AA Men n=243 n (%) |

AA Women n= 238 n (%) |

W Men n= 247 n (%) |

W Women n= 246 n (%) |

Total Sample n= 974 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | |||||

| 65-74 | 124 (51.0) | 113 (47.5) | 138 (55.9) | 131 (53.3) | 506 (52.0) |

| 75-84 | 91 (37.5) | 90 (37.8) | 87 (35.2) | 91 (36.9) | 359 (36.8) |

| 85+ | 28 (11.5) | 35 (14.7) | 22 (8.9) | 24 (9.8) | 109 (11.2) |

| Education ** | |||||

| Grades 0-8 | 124 (51.0) | 109 (45.8) | 37 (15.0) | 26 (10.6) | 296 (30.4) |

| Grades 9-11 | 51 (21.0) | 48 (20.2) | 36 (14.6) | 48 (19.5) | 183 (18.8) |

| High School | 30 (12.3) | 54 (22.7) | 77 (31.2) | 70 (28.5) | 231 (23.7) |

| > 12th Grade | 38 (15.6) | 27 (11.3) | 97 (39.3) | 102 (41.5) | 264 (27.1) |

| Income> $8,000 yr** a | 182 (24.4) | 117 (15.7) | 236 (31.6) | 211 (28.3) | 746 (76.6) |

| Income ≤ $8,000 yr ** | 61 (25.1) | 120 (50.6) | 11 (4.5) | 35 (14.2) | 227 (23.3) |

| Currently Married ** | 144 (59.3) | 48 (20.2) | 197 (79.8) | 113 (45.9) | 502 (51.5) |

| Household Size ** | |||||

| 1 person | 71 (29.2) | 90 (37.8) | 40 (16.2) | 108 (43.9) | 309 (31.7) |

| 2 persons | 106 (43.6) | 96 (40.3) | 183 (74.1) | 119 (48.4) | 504 (51.7) |

| 3 or more | 66 (27.2) | 52 (21.8) | 24 (9.7) | 19 (7.7) | 161 (16.5) |

| Mean MMSE Score (SD) | 22.7 (±5.4) | 23.4 (±5.2) | 26.6 (±3.5) | 27.7 (±2.6) | 25.1 (±4.8) |

| MMSE Score ** | |||||

| < 18 | 40 (16.5) | 32 (13.4) | 8 (2.0) | - - | 80 (8.2) |

| 18-20 | 33 (13.6) | 25 (10.5) | 8 (3.2) | 8 (3.3) | 74 (7.6) |

| 21-23 | 44 (18.1) | 44 (18.5) | 25 (10.1) | 11 (4.5) | 124 (12.7) |

| 24-26 | 58 (23.9) | 55 (23.1) | 44 (17.8) | 33 (13.4) | 190 (19.5) |

| 27-28 | 37 (15.2) | 56 (23.5) | 72 (29.1) | 77 (31.3) | 242 (24.8) |

| 29-30 | 31 (12.8) | 26 (10.9) | 90 (36.4) | 117 (47.6) | 264 (27.1) |

| Medical Conditions | |||||

| Hypertension ** | 178 (73.3) | 204 (85.7) | 145 (58.7) | 161 (65.4) | 688 (70.6) |

| TIA/Stroke | 33 (13.6) | 23 (9.7) | 31 (12.6) | 18 (7.3) | 105 (10.8) |

| COPD ** | 40 (16.5) | 13 (5.5) | 49 (19.8) | 30 (12.2) | 132 (13.6) |

| Diabetes* | 63 (25.9) | 80 (33.6) | 58 (23.5) | 44 (17.9) | 245 (25.2) |

| CAD ** | 44 (18.1) | 33 (13.9) | 87 (35.2) | 30 (12.2) | 194 (19.9) |

| Arthritis/Gout * | 108 (44.4) | 131 (55.0) | 98 (39.7) | 132 (53.7) | 469 (48.2) |

| Hip Fracture | 5 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.0) | 7 (2.8) | 19 (2.0) |

| Number of Comorbidities | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.2) |

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Fair or Poor Self-Rated | 123 (50.6) | 123 (51.7) | 96 (38.9) | 83 (33.7) | 425 (43.6) |

| Health ** |

P<.01

P<.001

data for variable missing for one participant

AA=African American, W=non-Hispanic White, MMSE=Mini-Mental State Exam, TIA=Transient Ischemic Attack, COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, CAD= Coronary Artery Disease

SPSS, version 16.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for descriptive analyses, bivariate comparisons, and multivariate linear regressions. Age adjusted values for BADLs, IADLs, and MMSE were calculated using the R statistical program.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Sociodemographic characteristics, MMSE scores, and medical conditions for the total sample are shown in Table 1. The mean (±SD) age of the 974 participants was 75.2 (±6.7). Compared to non-Hispanic White participants, African American participants were older [mean (±SD) age for Women, 76.2 (±7.4) and for Men, 75.2 (±6.6)]; were more likely to report 12 or fewer years of formal education, had lower income, were less likely to be married, lived in larger households (with three or more persons) and were more likely to rate their health as fair or poor. Overall, 28.5% of the total sample had MMSE scores < 24. Mean (SD) MMSE scores differed by race and sex. African American participants had MMSE scores distributed throughout all range categories whereas few non-Hispanic White participants scored in the lowest categories.

With regard to medical conditions, African American women had the highest prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and the lowest prevalence of COPD; African American men and non-Hispanic White men had the highest prevalence of stroke and COPD and non-Hispanic White men were more likely to have CAD. Women had the highest prevalence of arthritis/gout and non-Hispanic White women had the highest prevalence of hip fracture. There were significant differences between the race/sex groups with respect to education, household income, marital status, size of household, hypertension, COPD, diabetes, CAD, arthritis/gout, and self-rated health.

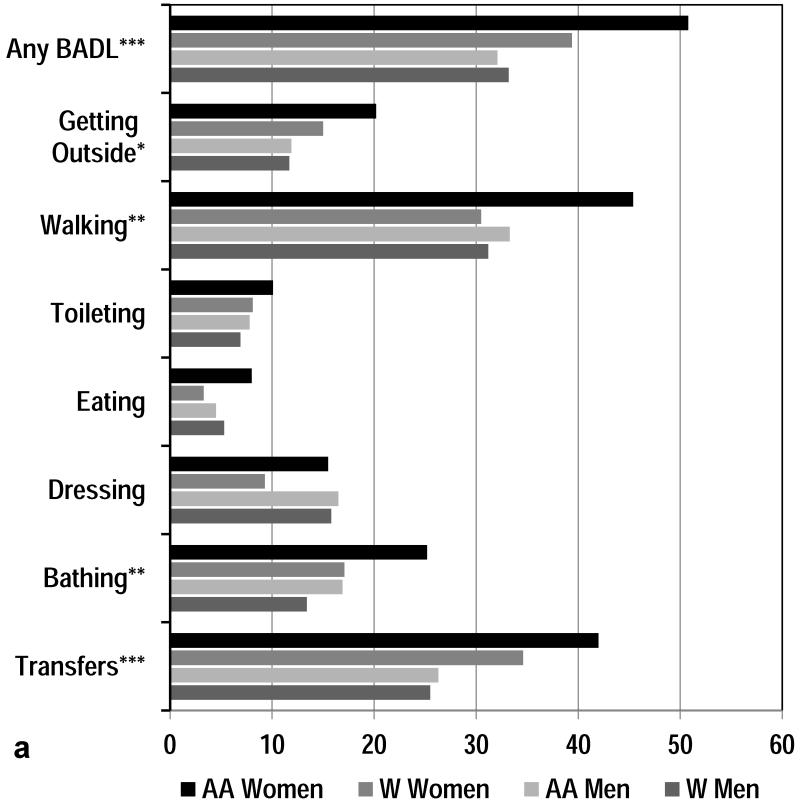

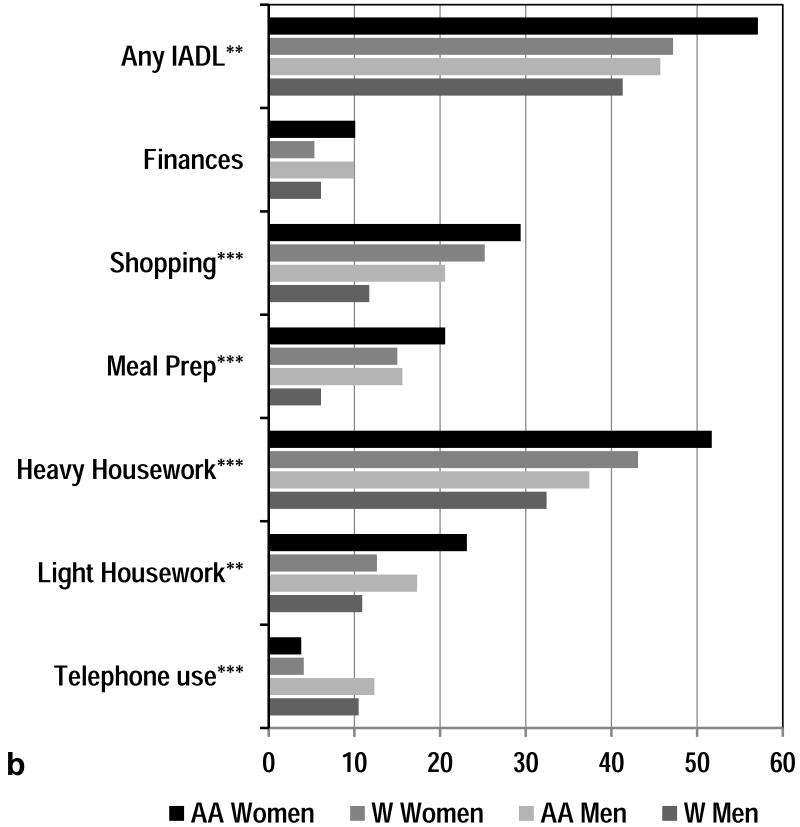

Prevalence of Functional Difficulty by Race and Sex

Overall, African American women reported greater difficulty with all BADLs and IADLs with the exception of dressing and using the telephone (Figure 1). Difficulty with mobility-related BADLs (walking and transfers) were more often reported by African American women as was heavy housework, the most physical of the IADL tasks. In comparison to men, non-Hispanic White women also reported significantly increased difficulty with transfers, revealing a sex disparity in this mobility-related daily activity. African American men and non-Hispanic White men demonstrated an equivalent prevalence of difficulty for all BADL tasks. However for all IADLs African American men reported greater difficulty compared to non-Hispanic White men.

Figure 1. Percentage by Race and Gender of Self-Reported BADL and IADL Difficulty.

*P<0.1, **P<.01, ***P<.001

BADL= Basic Activities of Daily Living

IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

AA= African American, W= non-Hispanic White

MMSE Scores and Functional Difficulty

African American women reported more functional difficulty than the other race/sex groups for both BADLs and IADLs (Table 2). To determine if older age explained observed variations in functional difficulty by race/sex groups, age adjusted BADL and IADL means were calculated. African American men reported more IADL difficulty than did non-Hispanic White men. In this sample, both unadjusted and age adjusted analyses indicated that women had higher mean MMSE scores compared to men (among same race category), and non-Hispanic White participants had higher mean MMSE scores compared to African American participants.

Table 2. Mean BADL Difficulty, IADL Difficulty, and MMSE Scores by Race and Sex.

| Race/Sex Groups | BADL * Mean (SD) Score | IADL ** Mean (SD) Score | MMSE Mean (SD) Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American Women | 2.1 (± 2.9) | 2.7 (± 3.8) | 23.4 (± 5.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White Women | 1.4 (± 2.5) | 1.9 (± 2.7) | 27.7 (± 2.6) |

| African American Men | 1.6 (± 3.2) | 2.3 (± 3.9) | 22.7 (± 5.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White Men | 1.4 (± 2.7) | 1.4 (± 2.6) | 26.6 (± 3.5) |

BADL (Basic Activities of Daily Living) Scores range from 0-21 where higher scores mean more difficulty

IADL (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) Scores range from 0-18

For the total sample, the Pearson coefficients for BADL and IADL difficulty with MMSE scores were −.269 (P<.001) and −.336 (P<.001), respectively. The negative correlations indicate that lower MMSE scores were associated with greater BADL and IADL difficulty for the total sample. We found significant inverse correlations for MMSE with BADL and IADL difficulty in all four race/sex groups. For BADL and IADL, respectively, the Pearson coefficients were −.194 (P<.01) and −.282 (P<.001) for African American women, −.189 (P<.01) and −.221 (P<.001) for non-Hispanic White women, −.380 (P<.001) and −.429 (P<.001) for African American men, and −.245(P<.001) and −.265(P<.001) for non-Hispanic White men. These correlations were greater among men than women.

The independent associations between MMSE scores and BADL and IADL difficulty are shown in Table 3. The unadjusted regression model showed that correlations of MMSE score and BADL or IADL difficulty had only trends toward significance. The multivariable, adjusted model indicates that the correlations for MMSE score and BADL or IADL difficulty were no longer significant in the total group after adjusting for demographic variables and number of comorbidities. The race/sex subgroup analysis suggested this was true for all race/sex groups.

Table 3. Unadjusted and Multi-Variable Adjusted Model Coefficients for MMSE with BADL Difficulty and IADL Difficulty in African American and non-Hispanic White Men & Women.

| Unadjusted Analyses | Adjusted Analyses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Unstandardized | Standardized | P Value | Unstandardized | Standardized | P Value | R2 |

| BADL | Beta | Beta | Beta | Beta | |||

| Total Groupa | .064 | .093 | <.001 | .021 | .037 | .219 | .09 |

| AA Womenb | .085 | .114 | <.001 | .045 | .055 | .373 | .08 |

| WhiteWomenb | .054 | .088 | <.001 | .028 | .052 | .371 | .20 |

| AA Menb | .064 | .090 | <.001 | .034 | .057 | .353 | .10 |

| White Menb | .054 | .083 | <.001 | −.022 | −.039 | .520 | .06 |

| IADL | |||||||

| Total Groupa | .079 | .098 | <.001 | .024 | .035 | .227 | .12 |

| AA Womenb | .107 | .112 | <.001 | .044 | −.056 | .342 | .16 |

| WhiteWomenb | .073 | .102 | <.001 | .052 | .089 | .122 | .19 |

| AA Menb | .087 | .099 | <.001 | −.001 | −.001 | .980 | .12 |

| White Menb | .053 | .086 | <.001 | −.005 | −.008 | .890 | .05 |

Coefficients adjusted for age, race, sex, education, income, marital status, number in household, and comorbidity count.

Coefficients adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, number in household, and comorbidity count.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides better understanding of the relationships between cognition assessed using the MMSE and day-to-day function among community-dwelling older adults in specific race/sex groups. Although MMSE scores were modestly correlated with both BADL and IADL in all race/sex groups, after multivariable adjustments for sociodemographic factors and health status, these associations were no longer significant in any group.

Our findings mirror those in the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) (10) as well as the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), but expand their relevance to both African American and non-Hispanic white men. In the WHIMS, only grip strength, but not gait speed or chair stands, was significantly correlated with Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) scores after full regression analysis (15). Together, these findings suggest that observed relationships between cognitive and functional status are largely mediated by sociodemographic factors and health status among older adults.

The MMSE has been criticized for its utility in diverse populations due to potential cultural and educational biases, brevity, lack of standardization in administration and scoring, challenges related to inter-rater reliability, and variance in the standard error of measurement (16). Many of the older participants in this study had historical barriers and financial pressures limiting both the quality and quantity of their education, potentially contributing to lower MMSE scores (3). In our analyses the MMSE scores varied by education as expected, but we found no significant difference in the reliability of the MMSE assessed by the Cronbach’s alpha for different racial/ethnic and education groups.

Our analyses revealed significant disparities in the prevalence of BADL and IADL difficulty, particularly comparing African American women with the other race/sex groups. These functional disparities were not explained by differences in MMSE scores among women, again consistent with previous reports (10). Measurement of other cognitive domains such as executive function (which is not fully assessed by the MMSE) may be more relevant to day-to-day function in our sample and warrants further study.

There are limitations to our study. Our cross sectional analysis used only a cognitive screening assessment and did not measure all domains of cognition. We cannot make inferences regarding etiology or rate of progression of cognitive decline. We did not include observable function measures and so self-reported functional difficulties may either overestimate or underestimate the true difficulty with day-to-day activities. Self-reports of IADL and BADL difficulty may be influenced by unquantified psychological, cultural, and cognitive factors. Additionally, this study was limited to older adults living in the Deep South, perhaps raising questions about generalizability of our findings. However, studying a diverse, community-based sample representative of the full continuum of cognition and function increases the relevance of our findings to many older adults.

Previous findings support that executive functioning predicts both self-reported as well as observed functional task performance (17). The findings in this analysis indicate that future research on cognition and function should perhaps focus on more practical day-to-day observed physical performance measures or ‘tasks’ or more complex functional tasks. Future research that includes functional assessments validated by surrogates may be helpful. Clinicians should avoid using MMSE as a surrogate measure for function in all race/sex groups and use appropriate, and ideally, observable measures to accurately assess those older adults with undiagnosed functional difficulty.

In conclusion, among community-dwelling older adults, cognition as measured by the MMSE was not independently correlated with self-reported day-to-day function in either African American or non-Hispanic White women and men. Associations between cognition and function were explained by sociodemographic and health variables. This study also highlighted that women reported more difficulty with mobility-related daily function than men, and African American women in particular reported more BADL and/or IADL difficulty than any other race/sex group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The corresponding author affirms that all persons listed as authors contributed significantly to the production of this manuscript. All contributors are legitimate authors.

Funding Sources

SLG was supported by Funding Support from a Diversity Supplement from the National Institute on Aging Grant # 3P30AG031054-06S1. PS was supported in part by Award Numbers R01 AG16062 and P30AG031054 from the National Institutes of Health. REK was supported in part by Award Number R01 AG16062 from the National Institutes of Health. RPS received institutional support provided by NIH/NCRR/RCMI Grant G12-RR03034 and U54 NS060659. HSS received support from Deep South Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (RCMAR) and Atlanta Regional Geriatric Educational Center (ARGEC)/COALESCE-(Collaboration Allows for Enhanced Senior Care) UB4HP19215. RMA was supported by Award Numbers R01 AG16062, P30AG031054, and 5UL1 RR025777 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

SLG | PS | REK | DM | RPS | HSS | RMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes /No | Yes /No | Yes /No | Yes /No | Yes /No | Yes /No | Yes /No | |

| Employment or Affiliation |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Grants/Funds | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Honoraria | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Speaker Forum | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Consultant | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Stocks | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Royalties | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Expert Testimony | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Board Member | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Patents | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Personal Relationship | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Author Contributions

Stephanie L. Garrett (SLG) - Concept, design, data interpretation, drafting, revision and final approval of manuscript

Patricia Sawyer (PS) - Design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting, revision and final approval of manuscript

Richard E. Kennedy (REK) - Data analysis, revision and final approval of manuscript

Dawn McGuire (DM) - Data interpretation, drafting, revision and final approval of manuscript

Roger P. Simon (RPS) - Data interpretation, revision and final approval of manuscript

Harry S. Strothers (HSS) - Data interpretation, revision and final approval of manuscript

Richard M. Allman (RMA) - Concept, design, data interpretation, drafting, revision and final approval of manuscript

Sponsor’s Role

All sponsors have funded the underlying research scope of all respective authors where related aims are applicable to this study. However, no specific sponsor was explicitly involved in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and/or preparation of this particular manuscript.

Contributor Information

Stephanie L Garrett, Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, 720 Westview Drive, S.W., Atlanta, GA 30310-1495.

Patricia Sawyer, Assistant Director, Comprehensive Center for Healthy Aging, Director, Gerontology Education Program, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294.

Richard E. Kennedy, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care CH-19, Room 201, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294.

Dawn McGuire, Neuroscience Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310-1495.

Roger P. Simon, Director, Translational Programs in Stroke, Professor, Medicine (Neurology) and Neurobiology, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310-1495.

Harry S. Strothers, III, Professor and Chair, Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, 1513 E. Cleveland Ave., Bldg. 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344.

Richard M. Allman, Parrish Endowed Professor of Medicine and Director, Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Comprehensive Center for Healthy Aging, Deep South Resource Center for Minority Aging Research, Co-Director, Southeast Center of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), 1720 2nd Avenue South, CH-19, Room 201, Birmingham, AL 35294-2041.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment without Dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle R, Lee B. Research Priorities in the Evolving Demographic Landscape of Alzheimer Disease and Associated Dementias. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(2):S64–S76. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00006. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowe M, Clay OJ, Martin RC, et al. Indicators of Childhood Quality of Education in Relation to Cognitive Function in Older Adulthood. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(2):198–204. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein J, Luppa M, Maier W, et al. (AgeCoDe Study Group) Assessing cognitive changes in the elderly: reliable change indices for the Mini-Mental State Examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2012;126(3):208–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephan BC, Matthews FE, Ma B, et al. Alzheimer and vascular neuropathological changes associated with different cognitive states in a non-demented sample. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(2):309–18. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AJ, Malladi S. Screening and Case Finding Tools for the Detection of Dementia. Part I: Evidence-Based Meta-Analysis of Multidomain Tests. Am J Geratr Psychiatry. 2010;18(9):759–782. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdecb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguli M, Rodriguez E, Mulsant B, et al. Detection and Management of Cognitive Impairment in Primary Care: The Steel Valley Seniors Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1668–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Robison JT, Tinetti ME. Difficulty and Dependence: Two Components of the Disability Continuum among Community-Living Older Persons. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:96–101. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leveille SG, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Black/White Differences in the Relationship Between MMSE Scores and Disability: The Women’s Health and Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B(3):P201–208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.3.p201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allman RM, Sawyer P, Roseman JM. The UAB Study of Aging: background and insights into life-space mobility among older Americans in rural and urban settings. Aging Health. 2006;2(3):417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allman RM, Sawyer Baker P, Maisiak RM, et al. Racial similarities and differences in predictors of mobility change over eighteen months. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1118–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. Assessing mobility in older adults: The UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10):1008–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkinson HH, Rapp SR, Williamson JD, et al. The Relationship Between Cognitive Function and Physical Performance in Older Women: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65A(3):300–306. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. Oxford Press; NY: 2006. 3rd Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grigsby J, Kaye K, Shetterly SM, et al. Executive cognitive abilities and functional status among community-dwelling older persons in the San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(5):590–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]