Abstract

For decades, public health advocates have confronted industry over dietary policy, their debates focusing on how to address evidentiary uncertainty. In 1977, enough consensus existed among epidemiologists that the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Need used the diet–heart association to perform an extraordinary act: advocate dietary goals for a healthier diet. During its hearings, the meat industry tested that consensus. In one year, the committee produced two editions of its Dietary Goals for the United States, the second containing a conciliatory statement about coronary heart disease and meat consumption. Critics have characterized the revision as a surrender to special interests. But the senators faced issues for which they were professionally unprepared: conflicts within science over the interpretation of data and notions of proof. Ultimately, it was lack of scientific consensus on these factors, not simply political acquiescence, that allowed special interests to secure changes in the guidelines.

FOR MORE THAN THREE decades, advocates of public health have confronted representatives of the food industry over questions of dietary or nutrition policy. Controversies over the validity of the science buttressing the policy and how public policy should address relative degrees of evidentiary uncertainty have informed these debates. Such debates have swirled around coronary heart disease (CHD), whose multiple risk factors are individually neither necessary nor sufficient. That is particularly true of the possible causal link of dietary fat and CHD; recognition by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute waited until 1984, despite the evidence from epidemiological cohort investigations, when it could support its position with results from a randomized controlled trial. It was the Lipid Research Clinic’s Coronary Primary Prevention Trial, a double-blind study, that finally convinced the institute that lowering serum cholesterol by using a drug (cholestyramine) significantly reduced mortality from CHD.1 Only after that trial did the Institute, following a consensus conference, adopt the link in formulating public health policy.

Ten years earlier, however, enough of a consensus existed among cardiovascular epidemiologists and nutritionists and within the American Heart Association that the important Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs (hereafter, “the committee”) used the diet–heart association to perform an extraordinary act: advocate dietary goals for the American population. This was “the first comprehensive statement by any branch of the Federal Government on risk factors [for chronic disease] in the American diet.”2 Its hearings, especially after its initial report, became an arena in which the scientific basis and political limits of that consensus were tested. The committee subsequently entered a bitter policy battle with various interests, in particular the meat industry, over its dietary recommendations. During this period, the committee produced two editions of its Dietary Goals for the United States. The first, in February 1977, encouraged people to “decrease consumption of meat,”3 whereas the revised, more conciliatory edition, published 10 months later, urged Americans to “decrease consumption of animal fat, and choose meats … which will reduce saturated fat intake.”4

Without providing a detailed account of the committee’s battles, nutritionist and activist Marion Nestle has characterized the revision as one of government surrender to special interests.5 To be sure, she is partially correct. Other histories have similarly characterized the committee’s actions, but without a close examination of the debates that occurred.6 However, a careful study of the committee’s activities is needed to reveal the complexities of this confrontation.7 Through such a narrative, we have shown that the committee, whose members included Ted Kennedy (D, MA), Hubert Humphrey (D, MN), and Robert Dole (R, KS), were faced with issues they were professionally incapable of resolving: conflicts within science over the interpretation of data, questions of scientific validity, and notions of proof. Ultimately, it was a lack of scientific consensus on all these factors, and not simply political acquiescence, that allowed special interests to gain a foothold in the debate and secure a modification of the initial guidelines on meat consumption.

FROM UNDER- TO OVERNUTRITION

The committee was created in 1968 after a CBS documentary, Hunger in America, revealed that too many Americans were suffering from undernutrition. Wrote Nestle,

The idea that people were going hungry in the land of plenty … elicited widespread demands for expansion of federal food assistance programs.2

The committee began life as a soldier in the War on Poverty. It was chaired from its inception by George McGovern (D, SD), whose interest in nutrition continued until his death in October 2012.9 By the early 1970s, the committee had orchestrated the passage of legislation that vastly expanded food stamp and school lunch programs and introduced the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

It was not entirely obvious, therefore, that the committee would make a priority of the relationship between “overnutrition” and the public health dimensions of chronic disease. In doing so, it was beginning to focus on public health in addition to public assistance. That shift occurred slowly, influenced by its outside advisors and by influential staff members. In the early 1970s, these included Nick Mottern, a journalist responsible for writing many of the committee’s reports; Alan Stone, who served as staff director; and Marshall Matz, general counsel. Matz, a young lawyer, was particularly important, as he essentially ran the business of the committee. On joining the Nutrition Committee in 1973, he became responsible “for recommending Committee policy in the areas of: food stamps, elderly feeding, diet and health, and human nutrition research” in addition to more routine activities, such as “supervising of staff, drafting legislation, initiating hearings and publications, and advising members of the Committee on legislative strategy.”10

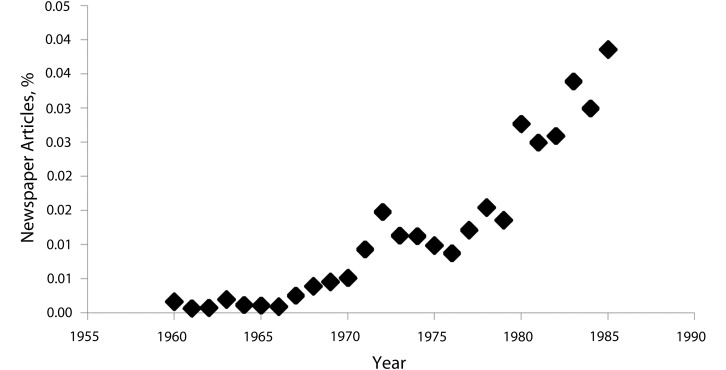

Matz, who had previously worked on a South Dakota Sioux reservation as a law fellow for the state’s legal services, had little interest in nutrition or its correlates with chronic disease before he joined the committee.11 He was influenced, however, by the committee’s outside advisors and hearings, especially its National Nutrition Policy Study Conference of 1974. In addition, both he and Alan Stone must have been aware of the growing public concern about nutrition and health reflected in the popular media. Reporters and columnists increasingly wrote about risk factors and disease prevention (Figure 1). Jeanne Voltz of the Los Angeles Times, for example, predicted in 1970, “Americans should be and will be eating more fish in the next decade [to] reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.”12 Jane Brody, a staff writer on health and science for the New York Times, was particularly concerned with the risk factors for chronic disease. In 1970 she featured the low-fat, low-cholesterol dietary recommendations of the noted CHD epidemiologist Jeremiah Stamler. Her article, she wrote, was in response to “numerous inquiries to the American Heart Association and the New York Times from persons seeking details on foods that do not clog the arteries.”13 Brody later reported on the Heart Association’s advice to Americans, contained in its 1973 cookbook, to modify their diets by reducing their consumption of fat to 35% of daily calories and by cutting cholesterol in half to no more than 300 milligrams per day.14

FIGURE 1.

Use of the Term "Risk Factor" in Major Newspapers, 1960-1985.

Note. Term appearing in full text in NY Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, LA Times, or Chicago Tribune.

For expertise, Matz and the committee turned to Jean Mayer, a Harvard professor of nutrition and an internationally recognized expert on hunger and obesity, and to his Harvard colleague, Mark Hegsted, well known for his research, including a mathematical model, the Hegsted equation, on the relationship between types of lipids consumed and their effects on cholesterol levels in the blood.15 In 1969, Mayer had chaired the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health requested by President Nixon (and supported by McGovern’s committee) to explore what policies were required to eliminate poverty-related malnutrition and to enhance nutrition-related health in the United States.16 The latter included discussion, influenced in part by population-level studies and the early heart disease clinical trials, of the possible link between the overconsumption of calories, cholesterol, and saturated fats and the rising rates of chronic disease.17

The committee also developed a supportive relationship with Dr. Robert Levy, director of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, whose research included large studies of the effect on serum cholesterol of drugs and diet.18 Before assuming the directorship, he had been the project officer heading the multicenter Coronary Primary Prevention Trial.

An important transitional event for Matz and the committee was the National Nutrition Policy Study Conference that Jean Mayer organized in 1974; this was a follow-up of his White House conference, spurred by the committee’s concern for rising food costs, meat in particular, in the United States.19 But, as in 1969, overconsumption and chronic disease was an important theme as well.

Invited to the conference were nutritionists, consumer advocates, farmers and food industry executives, physicians, and public health officials, some of whom were asked to produce task force reports. Panels of experts observed that the nation’s poor were suffering from inadequate nutrition, squeezed by price inflation that outpaced any rise in food stamp allowances.20 One report, derived from a Center for Science in the Public Interest, estimated that humans consumed up to one third of the pet food sold in urban slums and that some seniors, too, were turning to it to supplement meals. Press interest in the story was substantial, with some journalists and readers rejecting the findings.21 Participants were also concerned about a pending food crisis in poor nations, foreseeing famine in large parts of the world that might affect US security needs.22 Critics scored the meat industry for the immorality of fattening cattle with grains required by the world’s poor, as well as for its high domestic prices. Adding to the indictment against the industry was meat’s potential link to the growing national incidence of chronic disease. Among those questioning the role of beef in the American diet was Hegsted, who had concluded that cholesterol and saturated fat were implicated in the high rate of heart disease in the United States.23

Among the goals of the 1974 conference was the creation of a new federal agency that would develop a national approach to nutrition and create a food reserve to respond to famine in developing nations. Propitiously, Ted Kennedy, in his opening remarks at the conference, turned that policy on its head, drawing attention to an alternative form of malnutrition: “Although the children of West Africa melt away from starvation, Kennedy intoned,

America stands in ironic contrast as a land of overindulged and excessively fed. In many ways the well-being of the overfed is as threatened as the undernourished.24

By 1976, the relationship between nutrition and health had become a major preoccupation of the committee; they were particularly interested in “food additives and health, diet and disease, nutrition research, and the monitoring of nutritional health.”25 According to staff documents, the committee strongly believed that millions of American consumers wanted better health information and safer food.26 Traditionally, issues of food protection and information were the domain of the Food and Drug Administration. The Food and Drug Administration, which conducted scientific research on food and nutrition, took a conservative stance, barring claims on food labels that associated cholesterol with heart disease; by 1973, for the sake of patients on restricted diets, it permitted product labels listing cholesterol and fat content. However, the committee held that Americans needed more than nutrition information derived from labels, namely explicit advice on what to eat to be healthy. The committee, staff documents indicate, believed that current government policies were insufficient, and, therefore, “congressional oversight of nutrition and health” was an “urgent matter.”27

With the select committee’s focus shifting toward nutrition and disease, Matz reached out to the parent Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, which had usually been thought of as concerned more with the interests of farmers, ranchers, and agribusiness than with those of consumers. In July 1976, he sent a letter to staff director Mike McLeod, observing that despite its success in broadening public assistance to the poor and poorly nourished, the committee’s work was unfinished.28 Signaling the shift in its upcoming work, Matz argued,

It is time for our nation’s ‘nutrition program’ to broaden beyond a food distribution system. The problem of malnutrition in the United States is also a problem of overconsumption, and undereducation.29

In a statement that echoes current public health messages, he wrote,

Obesity … is the most serious malnutrition problem in the United States today, greatly increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.30

Hoping to convince the Agriculture Committee of the need to integrate food and agricultural policy, he spoke of “mounting evidence that many of our health problems are nutrition related” and that present American diets were linked to five leading killer diseases—heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, and cirrhosis of the liver.31 Within the month, the Senate Select Committee held its first hearings to find ways to reverse this course toward nutrition-related illness.

INDUSTRY ALARM

The threat of new select committee hearings following the National Nutrition Policy Conference alarmed David Stroud, president of the National Live Stock and Meat Board, a Chicago-based organization representing the interests of beef, lamb, and pork producers. Stroud, who became chief executive officer and president of the Meat Board in 1968, having spent years in staff positions there, was quicker than most to recognize that the industry had to defend itself.32 In a February 1976 confidential report, he alerted members of the potential for “serious erosion in [the] market position” of beef, noting that in the preceding years the meat industry had “been the focus of serious and sustained criticism on moral, economic and health grounds.”33 Stroud was aware of the select committee’s high standing and the fact that its reports were the most sought after among Government Printing Office publications.34

In addition to the committee, Stroud realized his industry faced a growing consensus among scientists and nutrition professionals that meat was harmful to Americans’ health. His confidential Meat Board report warned of the potential damage a continued focus on beef and nutrition could wreak and alerted members they should anticipate “some tough questions about the necessity of the meat industry at all” and “be prepared with responses based on facts to dispel misconceptions.”35 Stroud recognized that as a consensus on meat and disease gained traction among scientists, scientific evidence would have to support the industry’s response at any future congressional hearing for it to appear credible to Congress and the national press.36

INITIAL HEARINGS ON DIET RELATED TO KILLER DISEASES

The first hearings heralding the committee’s new interest, held in July 1976, fell under the title Diet Related to Killer Diseases. These sessions, eight in all extending to October 1977, provided a forum for senators to hear from leading scientists, government officials, and business representatives about the risks that US dietary consumption posed for heart disease, cancer, and other chronic diseases. In his opening statement, McGovern claimed that his goal was “simple: a healthy population” and that a prudent diet could “greatly affect the incidence with which the various killer diseases strike.”37 Foreshadowing the debates that were to come, another senior senator, Charles Percy (R, IL) noted that it was “not easy to prove the causes of disease beyond a shadow of a doubt” but that scientific experts had “found enough incriminating evidence to conclude that our super-rich, fat-loaded, additive and sugar-filled American diet” was “sending many of us to early graves.”38 His use of evidentiary language was closer to that of a lawyer than of a scientist or health policymaker.

Of those who gave testimony at the first hearings, perhaps the two most important were assistant secretary for health and former director of the National Heart and Lung Institute, Theodore Cooper, and Professor Hegsted. Cooper focused on the relationship between diet, fat, cholesterol, and heart disease. There was, he noted, a relationship

between the quantity of dietary fat and its qualitative makeup and the blood lipids … [that had been] established by research … carried out in cooperation with the National Heart and Lung Institute.39

The problem, however, was in connecting the dots. For the Institute, there was

not enough experimental evidence to establish that … the dietary fat pattern leads through elevation of B-lipoprotein [low-density lipoprotein] or cholesterol blood levels to the development of atherosclerosis.40

Like others, Cooper underscored that even if the dietary fat and cholesterol hypothesis

was completely unsubstantiated by future research, there is nothing … in the recommendations to reduce fat intake [that] would in any sense be harmful.41

Hegsted was more emphatic. Although noting that the evidence for an association between diet and most disease was “epidemiologic,” he felt that the link running from diet to serum cholesterol to atherosclerosis was obvious, noting that there was “a clear linkage between plasma serum lipids, atherosclerosis and coronary disease” and that it was “clear that diet controls cholesterol levels.”42 Hegsted believed that “the prudent diet for Americans” is one that emphasized eating

less food, … meat, … fat, particularly saturated fat … cholesterol, … [and] sugar … [and] more unsaturated fat … fruits, vegetables, and cereal products, particularly those made of whole grain cereal.43

Like Cooper, he believed that there were no known risks in following these recommendations, whereas the risks inherent in the typical American diet were high.44 Thus Hegsted was urging action on the basis not of evidence of a demonstrated direct relationship between exposure and outcome but of a combination of limited studies, prevailing scientific opinion, and risk–benefit probabilities. When controversy later arose with the meat industry after the committee published its dietary recommendations, Senator McGovern used Hegsted’s precautionary argument in defending his committee’s actions.

Half a year later, on January 14, 1977, supported by the evidence presented at its hearings, the committee released its landmark report, Dietary Goals for the United States. At a press conference on the day that the report was released, McGovern expressed a hope that the report would “perform a function similar to that of the Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking.”45 Hegsted, who also addressed the press, sought to weaken barriers to dietary change by characterizing the American current diet as one that was unplanned and illogical, “a happenstance related to our affluence, the productivity of our farmers and the activities of our food industry.”46

The goals in the report were stated very clearly. Of the six that were listed, half were of concern to the meat industry. They urged Americans to reduce their saturated fat consumption to no more than 10% of calories and daily cholesterol intake to 300 milligrams.47 The report explicitly suggested that people “decrease consumption of meat and increase consumption of poultry and fish.”48

On the heels of the release of Dietary Goals, the committee held new hearings on Killer Diseases. Among those testifying was National Heart Lung and Blood Institute director Robert Levy. The diet–lipid–heart disease hypothesis was a central focus of the hearing. Discussing the evidence, Levy observed,

With cholesterol the issue is a little more murky. We have no doubt from the vast amount of epidemiological data available that elevated [blood] cholesterol is associated with an increased risk of heart attack, especially some specific types of … cholesterol. We have no doubt that cholesterol can be lowered by diet, and/or medication in most patients. Where the doubt exists is the question of whether lowering cholesterol will result in a reduced incidence of heart attack; that is still presumptive. It is unproven [in clinical trials], but there is a tremendous amount of circumstantial evidence… . There is no doubt that cholesterol can be lowered by diet in free living populations. It can be lowered by 10 to 15 percent. The problem with all these trials is that none of them have showed a difference in heart attack or death rate in the treated group.49

Levy was consequently unwilling to issue the same recommendations on dietary cholesterol that the American Heart Association had done, apparently because he did not believe the scientific proof existed. During the questioning of both Senator McGovern and Senator Percy, Levy spoke again on the scientific evidence question:

Senator McGovern: There is no real doubt in your mind, is there, Dr. Levy, that proper diet can be a very important factor both in reducing the incidence of heart attacks in this country, and also in reducing hypertension among a great many Americans without, in many cases, any uses of drugs?

Dr. Levy: I would say that personally, as a public health professional, I agree completely with your comment. Where doubt exists, as a scientific question, is whether specific lowering of cholesterol, changing the amount of saturated fat in the diet of the average American will prevent heart attack. Personally, I feel that the answer is yes. Scientifically, we are committed, that is the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is committed, to getting that final piece of evidence, so we can go out with a massive health campaign.50

Jeremiah Stamler, one of the eminent CHD epidemiologists of his generation and perhaps the leading proponent of the diet–lipid–heart hypothesis, also testified at the hearing. Stamler presented ecological evidence from the Seven Countries Study led by epidemiologist Ancel Keys at the University of Minnesota as well as evidence from dietary modification trials performed on primates.51 Both studies suggested that a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet could reduce heart disease.

During Stamler’s testimony, Senator Percy specifically asked why he remained so convinced when there was still disagreement in the scientific community. Stamler admitted that the evidence from the epidemiological studies remained “encouraging, but not conclusive” of the diet–lipid link to heart disease52:

No full-scale unifactor diet–heart study is underway or planned—nor is it really feasible at present. Hence our preventive efforts in both the complementary medical care and public health arenas must proceed based on the vast evidence in hand from animal–experimental, clinical–pathologic and epidemiologic research over decades, and without “final” evidence from a “perfect” trial. Such a situation is common in the affairs of man in general, and in the health arena in particular… . The potential risks are essentially nil, the potential benefits vast, and that constitutes an optimal public health and medical care situation.53

A THREAT TO THE INDUSTRY

Not surprisingly, David Stroud contested the scientific basis for the recommendations of Dietary Goals, arguing that “much of the poor advice has come from zealots with a good deal to say but little to no scientific evidence supporting their positions.”54 Seeking to influence the committee’s future activities, Stroud suggested that some of the Meat Board’s staff should

meet for a thoughtful, unheralded discussion with the committee administrative staff to review points at issue and to develop a course for further studies and gathering of information.55

That meeting occurred on March 3, 1977, and Matz and Nick Mottern arrived to find Stroud unprepared and unable to discuss the science behind the report.56 Not surprisingly, the meeting was recounted in an extremely negative light by Meat Board Reports, the tabloid newsletter for the industry:

The staff people of the [Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs] told us in a four hour (friendly) session last week that they believed they had heard the best medical and health opinion on this matter… .In fact, they have not gained majority expert opinion. They have listened only to the clique of promoters holding this point of view, whose motives are questionable.57

Each side claimed to have medical consensus in its favor, and it was clear that science was going to take center stage in this debate. It did not matter to the Meat Board that Stroud had been unable to respond scientifically to the report, because McGovern had agreed by the time of the meeting for a March hearing at which scientists could present evidence that supported the meat industry’s case.58 He and Robert Dole, among other senators on the committee, were from cattle-raising states. The American National Cattlemen’s Association president, Wray Finney, hailed this as a chance for the committee to “conduct a truly unbiased examination of all the facts” so that Americans would receive “a balanced, correct view of this whole matter.”59

One week before the hearing, Stroud sent Matz a list of witnesses that included himself; Finney; Sir John McMichael, one of Britain’s premier clinical cardiology investigators and a caustic critic of epidemiology and “the American cholesterol hypothesis”60; and Rockefeller University lipid investigator E. H. “Pete” Ahrens. Ahrens, a leading clinical nutrition researcher, pioneered in the experimental use of precise liquid food formulas. Feeding small groups of individuals under controlled conditions on metabolic wards, he demonstrated that lowering saturated fatty acids reduced serum cholesterol.61 After Ahrens’s death in 2000, a peer described him as possessing “an inner sense of righteousness”62 and of never hesitating to express his mind. To such contemporary epidemiologists as Henry Blackburn, he was a source of frustration and resistance. Blackburn characterized Ahrens as “the prototypical clinical investigator, … firmly academic and resistant to making public health recommendations in the absence of experimental ‘proof,’ whether or not it was possible to obtain such proof.”63

PREPARING TO USE SCIENCE AND POLITICS

After McGovern’s agreement to hear the concerns of the meat industry, Matz began to coordinate the committee’s response. In a memo to McGovern, he argued that the meat industry was “not accurately assessing the shift in established thinking within the medical community.”64 By highlighting the dissonance between prevailing scientific opinion and the industry’s position, Matz hoped to portray the industry as being out of step with mainstream views:

They are continuing to pursue the time-honored approach of saying that the experts disagree, therefore how can anyone take a position. The truth is that the experts are not unanimous but there is more and more of a consensus. And the longer they pursue the shoot-out of the experts and avoid addressing how to deal with the economic consequences, the worse off producers … are going to be.65

Matz then argued that McGovern should make himself the broker between this new nutritional direction and the needs of livestock producers:

This brings me to the posture that I think you should take. For the industry to attack you is to go after the messenger. If they continue to make the potato too hot to handle, Ted Kennedy … or someone without a farm constituency, will take up the slack. You ARE best serving the needs of South Dakota by apprising the industry of a shift in medical thinking.66

Overall, Matz reminded McGovern that the dietary goals represented prudent recommendations that should not be compromised.67 He further noted that the report had generated a new constituency for McGovern that would be lost if he yielded to pressure.68 At the same time, Matz advised the senator to assure the meat industry that their economic interests would be protected. McGovern’s prepared statement included observations that “nowhere in the report” did “it say that diet or meat consumption causes any disease,” and that he considered beef to be “an excellent source of protein.”69

THE LIMITS OF SCIENTIFIC CONSENSUS

The new hearing in the Diet Related to Killer Diseases series was held on March 24, 1977. It was dominated by questions about conceptions of proof and whether current knowledge justified public health action in the form of dietary guidelines. An exchange that occurred between McGovern and Ahrens over the results of an international survey conducted by the Norwegian lipid scientist Kaare Norum of Oslo University is the clearest example of these debates. The questionnaire on diet and disease polled 209 experts that Jean Mayer characterized as a ‘Who’s Who’ of nutrition researchers, [including] physicians, nutritionists, epidemiologists, geneticists and others who are studying lipids and atherosclerosis.”70 As a politician, McGovern was more familiar with polls, such as the Oslo survey, than with analyzing study data. Matz had relentlessly argued that the meat industry was outside the scientific consensus, and the Oslo survey would demonstrate that. As a laboratory and clinical researcher, Ahrens was highly skeptical of biomedical research methods that differed from his own. McGovern’s questioning of Ahrens with regard to the Oslo survey brought this dynamic into play:

Senator McGovern: They then asked: “Do you think our knowledge about diet and coronary heart disease is sufficient to recommend a moderate change in diet for the population in an affluent society?” Of these 200 doctors, 91.9 percent answered “Yes,” that they thought that we now have enough evidence to recommend a moderate change in diet. They then indicated the order of priority in which those changes should be made: (1) less total calories, (2) less fat, (3) less saturated fat, and (4) less cholesterol. How do you react to almost 92 percent of the doctors who say they favored these moderate changes in diet based on the evidence we now have?

Dr. Ahrens: Senator McGovern, I recognize the disadvantage of being in the minority as I have been on this… . Yet it is an issue in which I have an enormous stake, and which I hope will someday be resolved. But I feel as a scientist that the most difficult thing in science is the getting of adequate proof… . The proof is not there yet. I think it might be profitable to look at the composition of the 209 people in [the Oslo survey]. I have done that this morning, and have selected the names of the people who have actually worked in this field themselves and therefore have the best right to an opinion. I have identified of the 209, only 47 people in this long list who have themselves experimented in the area of lipid nutrition, or fat metabolism, in man… . The persons I have not selected … have not been involved personally in fat feeding experiments, and the evaluation of those experiments, either in man or in animals.71

Thus Ahrens only considered valid the scientific opinion of bench and clinical researchers, particularly those like him who conducted highly controlled experiments; this ruled out many nutritionists—and epidemiologists in particular.

The two men also disagreed over what standards of evidence were needed to act. McGovern, as a political creature, felt compelled to act against a threat for which a growing consensus favored a particular intervention.

Senator McGovern: If you were sitting where we are, and you read that 92 percent of these doctors surveyed have changed their own dietary patterns, 92 percent of them said they are sufficiently convinced they are going to reduce the fat in their diet, don’t you think as Members of the Senate we have some obligation to make that information known to the people of this country and to recommend some changes? … It seems to me that what we are recommending here is a prudent moderate change in the diet based on an overwhelming probability. Do you agree or disagree with that?72

But Ahrens, fearful of a false positive error, needed experimental or trial proof that a certain course of action, dietary modification, would prevent atherosclerotic heart disease before a policy could be implemented. Without such proof, it was dangerous for the government to recommend dietary changes. Such approval seemed to imply that following the goals would make people healthier, a proposition that, for Ahrens, lacked scientific support. To the committee he said,

I understand perfectly the position you are in, and I sympathize with it. I think if I were in your position I would have reacted the same way. My contention is, however, that this is a matter of such enormous social, economic and medical importance, that it must be evaluated with our eyes completely open… . I submit that 160 people in this survey of Dr. Norum’s have not worked directly on the questions being debated. They have attempted to inform themselves as you have, by reading the literature. They are betting, and they are hoping. I am betting and I am hoping, too, for I have changed my diet to some degree, no question about it. I have done so in the hope that I am stepping off in the right direction. But I have no conviction nor foreknowledge that what I am doing is prolonging my life or that of my family.73

Still unsatisfied, McGovern continued to press Ahrens on how much certainty was needed to justify public health action.

Senator McGovern: Where is the greatest degree of risk? Because we are dealing with probabilities, rather than scientific fact, if you wanted to follow the prudent course, where you minimized the danger of risk, would you generally follow the recommendations for dietary goals set by our committee, or would you say to ignore them?

Dr. Ahrens: It is a matter of balancing the risks and the benefits. I truly believe the risks and the benefits are both very small. I think your report should emphasize the uncertainties that still exist and should not imply that by heeding these recommendations the public will reduce its risks of suffering the several diseases identified in this report.74

Although political pressure was already exerting its pull on the committee, Ahrens’s testimony played a significant part in legitimizing the meat industry’s efforts to change Dietary Goals. After the hearing, Bill McMillan, a lobbyist for the Cattlemen’s Association, wrote a thank you letter to McGovern stating that all the meat industry officials thought “that things went very well” and “were very satisfied with the presentation and Q&A involving the scientists and cattle producers.”75 McMillan also expressed hope that a supplemental report would be issued for Dietary Goals in light of the hearings, “so that a broadened piece of information” could be “made available to the general public.”76 Stroud, more combative, appears to have come close to demanding that either the publication of Dietary Goals be discontinued or a new edition be published in light of Ahrens’s testimony. This prompted a sharply worded response from Senator Percy, who wrote, “Positions should only change as a result of rationality and facts, not emotion or pressure.”77 However, that pressure did intensify over the coming months, resulting in both a concession from McGovern to revise Dietary Goals and subsequent confrontations among committee staff.

In a September 1977 memo, Matz wrote of the political realities resulting from the meat industry’s lobbying efforts and the need to revise the Dietary Goals, making the meat consumption recommendations, as we have noted, less stringent.78 But that second edition, appearing in December 1977, also underscored the contested nature of the scientific evidence required to produce the goals. It asserted that “science [could not] … at this time insure that an altered diet” would “provide improved protection from certain killer diseases such as heart disease.”79

In a September 23, 1977 memo to McGovern’s chief of staff, Matz highlighted the anger of the Nutrition Committee staff members over the revision of Dietary Goals. After being notified of the impending changes, Nick Mottern, who had drafted much of the initial Dietary Goals (heavily edited by Hegsted and other consulting scientists), demanded to meet with McGovern to review, one last time, the scientific arguments.80 Unsuccessful in changing McGovern’s decision, Mottern left the committee in November.

CONCLUSIONS

The need to issue a new edition of Dietary Goals underscored the degree to which the McGovern committee depended on science to formulate policy. In the end, it appeared that the committee was only responding to interest groups and political contention. But one should not ignore the questions of scientific proof that dominated the committee’s hearings on diet and heart disease. Although many in the nutrition and epidemiological communities seemed convinced of the diet–heart hypothesis, the lack of clinical trial evidence that nutritional changes would reduce CHD deaths left the National Heart and Lung Institute reluctant to officially recommend a low-fat diet as protective against heart disease. Without the imprimatur of the highest federal scientific authority on heart disease, the committee’s position was weakened. At the same time, the meat industry’s position was strengthened by the forcefully skeptical testimony of Dr. Ahrens, a disinterested and powerful scientific expert. Thereafter, the committee was left to debate probabilities and, in effect, the precautionary principle: was there sufficient scientific knowledge to develop dietary guidelines for Americans? How could the committee defend itself against scientific opposition? The consequence was a compromise. Once scientific consensus eluded the committee, it fell back on political consensus; even so, despite Marion Nestle’s criticism, it was more a limited retreat than a capitulation.

Dietary Goals was the last act of the committee, whose social activism was becoming socially atavistic. Created to serve a special purpose, a select committee expires, unless renewed by the Senate. After December 1977, not so renewed, the committee ceased to exist, its interests folded into those of the more industry-friendly Senate Agriculture and Forestry Committee, which added “Nutrition” to its title.81 McGovern headed its newly created Subcommittee on Nutrition until his defeat in 1980 at the onset of the “Reagan Revolution.”

The dietary guidelines the select committee produced, however, continued to reverberate. The publication had a significant effect on policy within the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services. In 1979, the latter produced Healthy People, The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, which made recommendations similar to the McGovern report; it suggested that Americans should reduce their serum cholesterol, associated with heart disease, by eating more fish and poultry and less red meat.82

A year later, both federal departments issued Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which Mark Hegsted, who had become administrator of the new Office of Nutrition of the Department of Agriculture, and his staff had written. In its rhetoric, it avoided the phrase “eat less,” calling instead for avoiding too much sugar, salt, fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol and favoring a varied diet, foods with adequate starch and fiber, and alcohol in moderation, if at all.83 In composing the report, which reiterated much of the Dietary Goals, Hegsted used the 1979 report of the American Society of Clinical Nutrition, which reacted to the scientific criticism of the Dietary Goals by conducting a review of the literature on diet and chronic disease and found that research supported the McGovern committee’s revised recommendations.84

But McGovern’s committee also aroused the opposition of various interests apart from the meat producers. The initial version of Dietary Goals for Americans alarmed the egg industry (which got its own committee hearing in 1977) and the American Medical Association, which rejected general guidelines in favor of physicians’ judgment tailored to the individual patient.85 Many nutritionists were both skeptical of the advice proffered by the Dietary Goals and professionally offended in that “a Senate Committee had no business getting involved in recommendations that ought to be made by the scientific community.”86 This was brought home most forcefully in 1980 when the authoritative Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council produced Toward Healthful Diets87; like Ahrens, it argued that evidence was insufficient to support a public policy that Americans decrease their dietary fat and cholesterol.88 With no cardiologists and epidemiologists as members, the board, which helped set scientifically based nutrition policy for the United States, nonetheless claimed its publication, not McGovern’s, represented scientific consensus.

The action of the Food and Nutrition Board underscores the difficult process of negotiating a consensus when so many interests are at play. Some on the board, according to its critics, were too closely associated with the diary, meat, and egg producers. As Matz stated, “the experts disagree; therefore, how can anyone take a position?” Here was a variation on the classic strategy of industry, the cigarette producers above all, to evade consensus by producing doubt and fostering controversy.89 But more to the point were the disputes within the nutrition profession and the debates that divided scientific disciplines, medical practitioners, and leading bureaucrats within the National Institutes of Health, debates over what constituted sufficient evidence, for whom, and with what subsequent actions and consequences. The epidemiologists and nutritionists who supported the diet–heart hypothesis could not successfully convince, coopt, or undermine their scientific opponents. The scientific consensus that Matz assumed was already sufficiently present, and that McGovern sought, remained elusive to experts and the committee alike.

A negotiated consensus over the diet–heart question took decades, as historians have noted.90 In 1979, the medical news section of the Journal of the American Medical Association could report, quoting a senior National Institutes of Health official, that

nutrition is the most politically charged area of science that I’ve ever seen. People go around, armed with very little evidence, wanting to sweep away dogmas and replace them with another group of myths just as bad.91

By 1990, however, a broad agreement existed among scientists, physicians, and National Institutes of Health bureaucrats, as well as consumers demanding knowledge of “safe foods,” a consensus that supported the goals and national policy that McGovern sought through the publication of the Dietary Goals for the United States. And many food producers ceased to fight the dietary guidelines, using them instead to market lines of “healthy foods.”

But the specter of “Pete” Ahrens still haunts the consensus. Is this again like a poll in which a group of nutritionists, physicians, epidemiologists, and health bureaucrats have fallen into step? How well will their position withstand the scrutiny of those with a different perspective on pathophysiology who are skeptical of the evidence underlying statements of causation? Are there alternative explanations that too are evidence based? Such controversies today swirl around salt, with some scientists and government agencies forcefully arguing that Americans should eat less salt to avoid hypertension and stroke, even as other scientists just as vociferously deny evidence for such health policies.92 Given that knowledge is always incomplete and consensus open to modification, public policymakers such as George McGovern are right to act, but in doing so they might also acknowledge the uncertainty of the scientific knowledge and the internal politics of the evidence-based, negotiated consensus they depend on.

Acknowledgments

This article was partially funded by the Professional Staff Congress, City University of New York (award 65044-0043).

The authors thank Ronald Bayer, David Johns, and Henry Blackburn for critically reading and commenting on earlier versions of the article and want to express their gratitude to the four anonymous reviewers who carefully perused the text and raised important questions. For her indispensible help in creating the graph, they also thank Dana March.

Human Participant Protection

Written permission was received from all individuals interviewed.

Endnotes

- 1. “The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial Results: I. Reduction in Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease,” JAMA 251, no. 3 (1984): 351–364; “The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial Results: II. The Relationship of Reduction in Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease to Cholesterol Lowering,” JAMA 251, no. 3 (1984): 365–374; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, “Consensus Conference: Lowering Blood Cholesterol to Prevent Heart Disease,” JAMA 253, no. 14 (1985): 2080–2090.

- 2. G. McGovern, Statement of Senator George McGovern on the Publication of Dietary Goals for the United States, Press Conference, Friday, February 14, 1977, in United States Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, Dietary Goals for the United States (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, February 1977), 1.

- 3. Ibid., 13.

- 4. US Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, Dietary Goals for the United States, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, December 1977), 4.

- 5. M. Nestle, Food Politics (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002)

- 6. K. D. Giffor. “Dietary Fats, Eating Guides, and Public Policy: History, Critique, and Recommendations,” The American Journal of Medicine 113 (2002): 89S–106S; D. Kritchevsky, “History of Recommendations to the Public About Dietary Fat,” Journal of Nutrition 128, no. 2 suppl (1998): 449S–452S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. Unlike previous accounts, we have constructed a historical narrative of the committee from 1976 to 1977 by using primary documents obtained from the George Stanley McGovern papers archival collection at Princeton University.

- 8. Nestle, Food Politics, 38.

- 9. “World Food Program Remembers George McGovern,” http://www.wfp.org/stories/wfp-remembers-george-mcgovern (accessed March 7, 2013); J. Siple, “McGovern Was Tireless Advocate for Hungry, Needy,” Minnesota Public Radio, October 22, 2012, http://minnesota.publicradio.org/display/web/2012/10/22/news/george-mcgovern-legacy(accessed March 7, 2013)

- 10. “C.V. of Marshall Matz,” George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Beef; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 11. M. Matz, personal communication, January 23, 2012.

- 12. J. Voltz, “Bigger Role Ahead for Fish on Menu,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1970: G1.

- 13. J. Brody, “Low-Cholesterol Recipes From a Meat Loaf Maven,” New York Times, December 18, 1970: 40.

- 14. J. Brody, “Heart Association Strengthens Its Advice: Cut Down on Fats,” New York Times, June 28, 1973: 54.

- 15. Giffor. “Dietary Fats, Eating Guides, and Public Policy”; M. Matz, personal communication, January 23, 2012; J. Pierce, “D. Mark Hegsted, 95, Harvard Nutritionist, Is Dead,” New York Times, July 8, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/09/health/09hegsted.html (accessed August 30, 2012)

- 16. White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health, Final Report (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1970)

- 17. Marion Nestle, Food Politics, 38–39.

- 18. M. Matz, personal communication, January 23, 2012; A. M. Gotto Jr, “In Memoriam: Robert I. Levy, 1937–2000,” Journal of Lipid Research 42, no. 5 (2001): 886–887. [PubMed]

- 19. “Senate Panel Sets Meeting on Nation’s Nutrition Policy,” New York Times (1923–current file), January 10, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times (1851–2008) with index (1851–1993): 75; J. Mayer, “Food for Thought: Another Look at Nutrition,” The Sun (1837–1985), May 12, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers The Baltimore Sun (1837–1986): T6; 27. “US Calls Talks on Meat Prices,” Chicago Tribune (1963–current file), June 17, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849–1988): B20.

- 20. W. Robbins, “US Needy Found Poorer, Hungrier Than 4 Years Ago,” New York Times (1923–current file), June 20, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times (1851–2008) with index (1851–1993): 81.

- 21. E. H. Peeples Jr, “Meanwhile, Humans Eat Pet Food,” New York Times (1923–current file), December 16, 1975; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times (1851–2009) with index (1851–1993): 39; M. Burros, “Pet Food Staple for Impoverished Americans,” The Washington Post (1974–current file). Washington, DC; December 7, 1975: 98; “Poor Eating Dog Food, pPnel Told,” Chicago Tribune (1963–current file), June 20, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Chicago Tribune (1849–1989): A11; L. Johnston, “Are Humans Eating Canned Pet Foot? The Growth of a Rumor: ‘It’s for … ‘” New York Times (1923–current file), November 26, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times (1851–2009) with index (1851–1993): 44.

- 22. W. Rice, “US Urged to Lead Food Reserve Plan,” The Washington Post (1974–current file), June 20, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post (1877–1995): A2.

- 23. “The Impact of Selected Attitudes Toward the American Livestock and Meat Industry. Some Observations of the Congressional Climate,” February 1976, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Beef; Public Policy Papers,Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 24. W. Robbins, “Nutrition Study Finds US Lacks a Goal,” New York Times (1923–current file), June 22, 1974; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times (1851–2008) with index (1851–1993): 21.

- 25. “Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs Agenda for Executive Session,” January 29, 1976, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 1002 Folder 1976; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. Letter to Mike McLeod, “Re: Making ‘Nutrition’ Part of a Food and Agriculture Policy,” July 7, 1976, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 1002 Folder C-76; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. Ibid.

- 31. Ibid.

- 32. “Past, Present and Future—National Meat Board Metamorphosis,” Meatingplace, January 1996, http://www.meatingplace.com/Print/Archives/Details/479 (accessed April 9, 2013); “Diet Policy Déjà vu,” http://beefmagazine.com/mag/beef_diet_policy (accessed April 9, 2013)

- 33. “The Impact of Selected Attitudes Toward the American Livestock and Meat Industry.”.

- 34. Ibid.

- 35. Ibid.

- 36. Ibid.

- 37. “Hearings Before the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate,” Diet Related to Killer Diseases, July 27–28, 1976” (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1976), 1.

- 38. Ibid., 2.

- 39. Ibid., 12–13.

- 40. Ibid., 13.

- 41. Ibid., 13.

- 42. Ibid., 209.

- 43. Ibid., 209.

- 44. Ibid., 209.

- 45. Dietary Goals for the United States, 1.

- 46. Ibid., 3.

- 47. Ibid., 12.

- 48. Ibid., 13.

- 49. Hearings Before the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate, Diet Related to Killer Diseases, II. Part 1. February 1–2, 1977 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1977), 12.

- 50. Ibid., 18–19.

- 51. Ibid., 261.

- 52. Ibid., 274.

- 53. Ibid., 274.

- 54. Letter to Senator Percy From David Stroud, February 4, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 55. Ibid.

- 56. “Memorandum to File Re: Meeting in Chicago,” March 4, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993, Folder Beef; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 57. Meat Board Reports, March 14, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library (parentheses and underlining in original)

- 58. W. Finney, “American National Cattlemen’s Association News Release,” February 16, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Meat; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 59. Ibid.

- 60. H. Blackburn, “Preventing Heart Attack and Stroke, a History of Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology,” Interview With A. Gerald Shaper, http://www.epi.umn.edu/cvdepi/interview.asp?id=64 (accessed March 27, 2013). Dr. Shaper was a student of John McMichael; J. F. Goodwin, “Profiles in Cardiology, Sir John McMichael, 1904–1993,” Clinical Cardiology 16 (1993): 453–455.

- 61. E. H. Ahrens, “After 40 Years of Cholesterol Watching,” Journal of Lipid Research 25, no. 13 (1984): 1442–1449. [PubMed]

- 62. J. Davignon, “Remembrance,” Cardiovascular Drug Reviews 20, no. 4 (2002): 240.

- 63. H. Blackburn, “Preventing Heart Attack and Stroke, a History of Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology,” Edward H. Ahrens, PhD, MD (1915–2000), file:///Volumes/NO%20NAME/GO%20Schtick%203.20.13/DOCS/CHD%20Edward%20Ahrens/ www.epi.umn.edu:cvdepi:bio.asp%3Fid-233.webarchive (accessed March 16, 3013)

- 64. “Memorandum to Senator McGovern Re: Reaction of Meat Industry,” February 23, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 65. Ibid.

- 66. Ibid.

- 67. “Memorandum to Senator McGovern on Television Appearance,” March 1, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Beef; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 68. Ibid.

- 69. M. Matz, “Opening Presentation A.M. America,” March 1, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Beef; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 70. J. Mayer and J. Dwyer, “Experts Polled on Diet, Heart Disease,” Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1978: K6.

- 71. Hearings Before the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate, Diet Related to Killer Diseases, III, March 24, 1977 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1977), 17.

- 72. Ibid., 18–19.

- 73. Ibid.

- 74. Ibid.

- 75. Letter from C. W. McMillan to Senator McGovern, March 29, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 76. Ibid.

- 77. Letter from Senator Percy to David Stroud, May 10, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers.

- 78. Memo from Marshall Matz to GVC [George V. Cunningham]; September 23, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 79. Dietary Goals for the United States, 2nd ed., December 1977: ix. Memo from Marshall Matz to GVC [George V. Cunningham], September 23, 1977, George S. McGovern Papers, Box 993 Folder Untitled; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 80. Ibid.

- 81. Letter from Senator Herman Talmadge, Chairman of the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry to Senator George McGovern, September 27, 1977, Box 1109 Folder Committee; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- 82. US Surgeon General, Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (Washington, DC: Department of Health Education and Welfare, 1979)

- 83. Henry Blackburn interview with Mark Hegsted, October 24, 2005; Nestle, Food Politics, 46–47.

- 84. Henry Blackburn interview with Mark Hegsted, October 24, 2005; Nestle, Food Politics, 42–43.

- 85. US Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, Dietary Goals for Americans—Supplemental Views (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1977)

- 86. Henry Blackburn interview with Mark Hegsted, October 24, 2005, http://www.foodpolitics.com/wp-content/uploads/Hegsted.pdf (accessed September 7, 2012); Nestle, Food Politics, 41.

- 87. National Research Council Food and Nutrition Board, Toward Healthful Diets (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1980)

- 88. Henry Blackburn interview with Mark Hegsted, October 24, 2005; Nestle, Food Politics, 47.

- 89. A. M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2007); D. Michaels, Doubt Is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008)

- 90. H. M. Marks, The Progress of Experiment (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997); J. A. Greene, Prescribing by the Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Disease (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 2007)

- 91. “Experts Clash on Nutrition Policy,” JAMA 242, no. 24 (1979): 2646. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92. National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010); R. Bayer, D. M. Johns, and S. Galea, “Salt and Public Health: Contested Science and the Challenge of Evidence-Based Decision Making,” Health Affairs 31, no. 12 (2012): 2738–2746; Institute of Medicine, Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013) [DOI] [PubMed]