Abstract

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (1909–1914) fielded a philanthropic public health project that had three goals: to estimate hookworm prevalence in the American South, provide treatment, and eradicate the disease. Activities covered 11 Southern states, and Rockefeller teams found that about 40% of the population surveyed was infected. However, the commission met strong resistance and lacked the time and resources to achieve universal county coverage and meet project goals. We explore how these constraints triggered project changes that systematically reshaped project operations and the characteristics of the counties surveyed and treated. We show that county selectivity reduced the project’s initial potential to affect hookworm prevalence estimates, treatment, and eradication in the American South.

FOLLOWING HIS SEARCH FOR evidence of hookworm disease in the American South, US Public Health zoologist Charles Stiles reported that hookworm, or uncinariasis, was

one of the most important … diseases of the South, especially on farms and plantations in sandy districts … and even some of the proverbial laziness of the poorer classes of the white population are … manifestations of uncinariasis.1

Stiles presented his findings on the hookworm Necator americanus at a 1902 Sanitary Conference meeting in Washington. His report attracted national attention in the New York Sun with the headline, “Germ of Laziness Found.”2

Internationally, medical recognition of hookworm disease had progressed rapidly after Italian physician Angelo Dubini reported 20 cases of intestinal worm species Ancyclostoma duodenale in 100 human autopsies in 1843.3 By the mid-1870s, European physicians had linked the parasitic worms to human symptoms of severe anemia, pallor, and weakness. In 1878, Italian physicians developed a test to identify worm ova in the feces of living patients.4 On the basis of this test, A. duodenale was linked to epidemic, fatal anemia among workmen building the Swiss St. Gotthard Tunnel in 1880 and to nonfatal, endemic anemia suffered by miners and brick makers across Europe.5 Hookworm disease was listed in European medical books by the 1880s; Stiles was introduced to it as a graduate student in Germany at this time.6 German public health authorities, already aware of hookworm disease in German workmen at the time of the New York Sun headline, had an effective control program under way by 1903.7

Although hookworm disease would not be formally recognized in US medical practices for nearly a decade after the Sun article, medical reports of probable cases sporadically appeared, including cases in St. Louis, Missouri (1893); Buffalo, New York (1897); Texas (1890s); and New Orleans, Louisiana (1899).8 Numerous US studies of associated symptoms such as severe anemia or pica (dirt- or clay-eating) were published as early as 1804.9 But clinical detection and public health intervention did not systematically begin in the United States until late 1909, when John D. Rockefeller provided $1 million of seed funding to establish the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (hereafter RSC) and hired Stiles and project administrators.10 The RSC announced three goals: to survey and map the hookworm prevalence in the South, to treat the infections found, and to eradicate the disease. RSC activities from 1909 to 1914 covered 11 Southern states; RSC hookworm infection findings indicate that about 40% of the Southern population was infected.11

Three waves of studies over the last century detail the larger role of the Rockefeller Foundation (founded in 1913) in medical history, US and international health and medical education, and economic history.12 The most recent wave examines various Rockefeller Foundation projects as national case studies, finding that Rockefeller policies and activities were contingent on national context. We follow this model to examine the RSC hookworm project in the US South. Because the RSC project could not—and did not—achieve universal coverage of the South, we examine the project’s implementation and empirically explore whether selective county participation occurred.

RURAL SOUTHERN ECONOMY AND HEALTH

The South at the turn of the 20th century had a changing regional economy and high regional rates of mortality and morbidity from smallpox, tuberculosis, malaria, and other diseases.13 Agricultural restructuring after the Civil War shifted farming from plantation to sharecropping, with tenant and landed farmers increasingly producing cotton as a single cash crop.14 Primitive living standards increased Black and White farm families’ vulnerability to disease. The risk of exposure to hookworm infection was great as well; John A. Ferrell noted that in the Southern rural sections,

open privies and, far too often, no privies at all, are used, [so that] millions upon millions of [hookworm] eggs are scattered over the earth, and develop into minute, infecting worms ready to attack.15

The climate favored wide regional geographic distribution of hookworm as the land, marked by warmth, moisture, and aerated sandy or loamy soils, allowed hookworm larvae to burrow for protection from the sun, perhaps for years. Hookworm also was endemic in the mining towns of North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia, where the parasite found protection in mines from extremes of temperature and dryness.16

Human transmission occurred as newly hatched hookworm larvae from eggs in contaminated soils entered hosts via direct, physical contact through a foot or hand. After penetrating the skin, they traveled to the heart and lungs and then to the small intestine, where they attached to capillaries to feed, remaining from 2 to 13 years.17 Females released thousands of eggs per day (9000–25 000) into the intestine, which, after expulsion from the human body into inadequately designed privies or moist dirt, hatched in the soil and waited to enter human hosts, thus completing the cycle.

Recent studies have found that individual risk of hookworm infection and disease (i.e., infection that progresses to symptoms) reflects exposure to larvae-contaminated soil on farms, in mines, and other sites favorable to worm and host vulnerability.18 But exposure to contaminated soil—or “soil pollution,” as termed by Stiles and RSC members—is mediated by not wearing shoes, poverty, and poor household and public sanitary conditions, especially the lack of plumbing or hygienic privies. Even prior to the RSC project, a study of four Southern states found that only about one third of farmhouses had access to a privy.19 Later, RSC sanitary surveys of all participating states found that the vast majority of rural schools and churches lacked a privy. In North Carolina, which became a progressive, bellwether state in public health,20 only 6 of 238 White schools and none of 20 Black schools had sanitary privies near the project’s start.21

SOUTHERN TOWNS, EARLY INDUSTRIAL GROWTH, AND HEALTH

Around 1880, the growing difficulty of maintaining living standards by farming drove social demographic change in the South. A mass rural exodus in the late 19th century fueled rapid town and urban population growth; Blacks entered Southern cities, although many would leave the South altogether after the end of World War I. Rural Whites, however, often moved to Southern towns and villages to fill a growing number of textile mill, saw mill, and other jobs generally closed to Black labor.22 Because the owners of most of the mills and mines provided housing along with jobs, families crowded into the small houses provided.23

It is unclear whether early Southern industrial development, given its containment in crowded, unsanitary textile and mining towns, benefited public health. Northern urban areas at the turn of the 20th century suffered relatively high levels of morbidity24; diseases were widespread in Southern towns as well.25 With regard to hookworm, rural residents, who generally had high infection rates, carried parasites to mill towns, mining towns, and other unexposed populations (e.g., military bases) in the process of migration or relocation. Stiles’s 1912 report on “cotton mill anemia” in five Southern states noted that one out of seven or eight mill workers harbored hookworm.26 Mills and mines suffered high labor turnover; in a sample of 91 mills, the report estimated that 75 of every 100 workers were replaced in a given year, generally by White tenant farmers arriving with families. Of every 100 replacement workers hired, about one fourth carried hookworm to the mills. Some labor turnover reflected “summer farming” or seasonal migration between mills and farms; turnover also reflected workers’ propensity to leave one mill for the next.

In addition, mill town soil pollution was widespread: in 68 sampled mill villages, only about 9% of dwellings had sewer connections while another 21% had privy styles that afforded minimal protections from soil contaminants.27 Thus, about 70% of Southern mill village inhabitants were without basic sanitary facilities, and hookworm may have been nearly as prevalent in textile towns as in rural areas or at-risk mines. Stiles, however, publicly maintained that hookworm prevalence was lower in mill towns than on farms and that early-20th-century mill town environments were better, not worse, for public health.28 Stiles’s claim may have been true—or he may have elected to assuage mill owners to gain their cooperation with RSC objectives and activities.29

Prior to the RSC campaign and perhaps as a harbinger of difficulties ahead, Stiles met resistance when introducing hookworm infection as a possible public health problem. An occasional parasitology lecturer at Johns Hopkins Medical School in the 1890s, he was unable to convince William Osler that Southern physicians were missing or misdiagnosing hookworm symptoms in what would be estimated to be about 40% of the Southern population. Osler downplayed the condition’s potential prevalence, noting in his 1890s medical textbook that “no recent observations have been made in this country.”30 A public health manuscript was returned to Stiles in 1903 with advice to delete a section on privies before publication because it was “exceedingly undignified, in fact disgusting, and had no place in a scientific article on public health.”31

This difficulty continued. The RSC annually assessed whether Southern newspaper reporting was favorable toward the project and related activities; the assessments determined that the Southern press was lukewarm to hostile until well into 1911.32 Medical practitioners, in community after community, ignored suggestions to test patients and screen local residents for hookworm.33 Indeed, pockets of resistance remained well after the RSC project ended. In military medical practice, Charles A. Kofoid, a major in the US Sanitary Corps, claimed that among “medical men from all parts of the country, especially the South” there was “apathy … and non-concern of the greater rank and file of the medical profession to [hookworm] disease and its consequences.”34

INITIAL PROJECT PLANNING

The RSC’s novel public health initiative generated considerable headwinds requiring (re)alignment and engagement with different parties and participants: medical practitioners, political and business leaders, the press, state and local public health personnel, and the lay public. RSC and state administrators encountered uneven local public and medical cooperation at best and often active resistance to public health activities.35 Some Southerners resented the Northern roots of the project, and others objected to discussions about privies. But in general, the RSC’s biggest problem was its inability to convince a skeptical public about hookworm and its supposed prevalence. Facilitating hookworm’s camouflage in living cases was its hidden natural life cycle, unfolding in the soil or deep in the human gut. Moreover, wide-ranging and ambiguous manifestations of hookworm disease, including weakness, gastric distress, dizziness, headache, coughing, and breathing problems, could be symptomatic of other prevalent diseases such as malaria, poor nutrition, pellagra, or tuberculosis.

A basic problem had to be resolved before headway could be made: how might hookworm infection be defined or understood as a condition of poor health? Many in the South, including physicians, did not view hookworm’s symptoms as “sickness” or open privies as “risks.” They were accustomed to the symptoms in the people around them and to the sanitary facilities commonly in use. By contrast, Stiles and RSC agents viewed hookworm infection through the lens of the new germ theory.36 In their view, hookworm was a disease agent spread by soil pollution, with most of the Southern population either “sick” or “at risk.” They focused on unsanitary practices precisely because they were commonplace. Changed understandings, on all sides, needed to occur.

Nine states participated in the project in 1910: Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. Florida initiated its own state hookworm program prior to 1910 and, although RSC officials visited the state, it did not participate. Kentucky was the 10th state to join, in 1911, and Texas was added in 1912. The commission understood that they, as an outside agency, could not accomplish screening, treatment, and eradication alone. The first Annual Report notes “if the infection is to be stamped out, the States in which it exists must assume the responsibility.”37

The RSC set up a vertically organized program using a germ-theory-oriented approach to combat the disease38: it targeted the single agent hookworm for treatment and, to address prevention, surveyed the presence and quality of local sanitary facilities. As Wickliffe Rose, the first RSC secretary, noted, “Hookworm disease is preeminently a soil pollution disease … communicated from one person to another only through polluted soil.”39 Viewing states as units of organization, the RSC underwrote varying but considerable shares of the cost of hiring persons to state public health positions who were dedicated to the RSC project.40 It placed agents, or coordinated with existing state officials, to channel resources and hookworm-specific activities across agencies within each respective state. The commission noted that

each state has its own system of public health, its own system of organized medicine … and a host of minor agencies which can be used to advantage.41

States were to appropriate and expend their own funds for screening and prevention as well.

The state-administered programs initially guided local (county) site selection procedures: RSC state operatives, traveling from county to county and town to town, targeted rural and coastal temperate areas with sandy soils. Relying on visual inspection of local residents and anecdotal reports from sympathetic physicians and teachers, they estimated the prevalence of hookworm disease and whether local infection was “heavy” or “light.” Field operatives looked for basic visible symptoms of hookworm disease, including pallor, jaundice, pica, diarrhea, short height, low weight, and listlessness. Left untreated over time or if hosts were susceptible, hookworm disease produced severe stunting, emaciation, impaired mental development, and other characteristics that operatives identified in the heavily infected localities: waxy pale skin, flat affect with fixed facial expressions, protruding bellies, sunken chests, and wing-like shoulder blades.42 Thus, in the early years of the RSC project, a locality was targeted—or not—for further screening or intervention on this visual basis alone.

Yet RSC screeners also found individuals who looked and felt healthy but harbored or carried the worm; this is because a substantial number of worms could sometimes be well tolerated in otherwise healthy individuals without clinical manifestation.43 Although not understood at the time, the frequency distribution of hookworm in host populations is marked by overdispersion: most worm burden is harbored in a relatively small number of cases with high-intensity infections.44 For these reasons, early attempts at detection were not accurate or uniform. Physicians and the general public remained skeptical. Physicians balked at screening patients; the RSC estimated that only about 16% of practicing physicians in the nine participating Southern states in 1910 treated patients for hookworm.45 Also, many individuals infected with the worm refused treatment; the RSC found 42 946 positive cases in 1910, but only 14 400 were actually treated by being sent home with a dose of thymol for self- administration.46

SHIFTS IN LOCAL PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

The RSC’s initial adoption of a visual method to estimate local hookworm prevalence was not systematic or effective; the method missed cases, so the campaign soon shifted strategy. State and RSC administrators decided in February 1911 to field local prevalence surveys, sampling at least 200 rural children, often in schools, between the ages of 6 and 18 years taken at random (i.e., not based on a child’s appearance or symptoms).47 Diagnosis of hookworm was based on microscopic examinations of stool, not visual inspections.

There was no mention in 1911 or in subsequent Annual Reports about whether, or how, the selection of counties to be examined for hookworm might proceed; however, because of another project change, this may not have been a central issue in 1911. In a “surprising development,” RSC administrators found that the public was receptive to screening—and even treatment—when offered through the mechanism of public dispensaries.48 Supervised by state directors over an intensive six- to eight-week period, these locally organized dispensaries, which were one-stop shops, provided screening, the provision of medication, and, above all, public education about hookworm. For example, for a dispensary organized in Alamance County, North Carolina, in 1913,

the leading roads of the county were posted with large placards and small handbills giving … the dispensary points. More than a thousand circular-letters were mailed to leading citizens … public lectures were given at the different cotton mills and a public health demonstration was given at the Masonic picnic at Piedmont Park.49

Once at the dispensary, the public looked at hookworms in pictures and especially through microscopes, as “proof” of the worms and disease. Consequently, public views about the risk of infection changed; they more readily accepted testing and thymol treatment, and many returned to dispensaries for retesting after treatment to be sure that their worms—or those of their children—were gone.

The dispensary form caught on and quickly spread, with the motivation and means to set them up often coming from nearby county dispensary leaders, with state and RSC encouragement and support.50 And so, a highly visible, community-based public health demonstration model, not the medical practice model that encouraged local physicians to provide diagnosis and treatment, elicited community participation motivating behavioral change. With this “surprising development,” the RSC recognized it needed to do more than just coordinate with state departments of health; it also needed to cultivate “in each county a capable county superintendent of health devoting his whole time to public-health work.”51 This required not only states but counties to at least partially fund—above and beyond RSC and state-level funding—local public health activities and staff. Local action also required the commitment and mobilization of citizens: school board members, employers, and local elites such as women’s club members. However, the RSC still sought to maintain a vertically structured state program, primarily focused on one disease, while broadening the local bases of participation.

COUNTY SELECTIVITY

Given limited funding dollars, RSC and state officials initially concentrated visual screening efforts for heavy or light infection prevalence in counties where conditions posed the greatest potential exposure to infection, while also collecting data on privies for future prevention of soil pollution. The RSC had screened for hookworm on the basis of “theoretical conditions in respect to soil, races of inhabitants, and density of population.”52 Through extensive research by Stiles and others, it was well-known then, as now, that high-risk localities have warm climates, sandy soil, and abundant rain, but also—because soil pollution with hookworm involved deposits of human wastes—rural underdevelopment with regard to privies and plumbing.53 The evidence on race differences in hookworm was ambiguous in 1909, but RSC and military reports over the next decade reported—and contemporary estimates of RSC data find—that US Blacks had lower prevalence rates and intensity of hookworm disease, based on egg and worm counts, than Whites.54 Also, as noted by Stiles, infection

is more common in the country districts than in the cities. … On the farms and in the very small towns people are not so careful to prevent soil pollution, so that ground-itch is more common.55

Accordingly, the RSC should have sampled children in rural counties with lower population densities, where sandy soils and warm and wet climates perpetuated the hookworm life cycle.

But with the success of dispensaries and a growing RSC preference for—and reliance on—local activities and funding, the commission channeled its own resources and sampling efforts toward counties sympathetic to the public health project. One report noted that, with regard to the RSC hookworm prevalence and sanitation surveys, “those communities are preferred which have a well-marked progressive community spirit, centering, perhaps, in the schools in the district.”56 Table 1 presents details of county dollars expended on program activities, by state, at the end of the dispensary program’s first full year, 1912. Significantly more dollars were expended by counties in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Georgia and, commensurate with higher local expenditures, more dispensaries were set up in these counties. RSC state funding levels were associated (not perfectly) with the states’ county-level expenditures. Local effort was not simply a function of the early timing of a state’s entry into the RSC activities but reflected early local investments, in key states, in public health.57 Georgia had the highest and Virginia the lowest hookworm rates.

TABLE 1—

County Hookworm-Related Expenditures and Rockefeller Sanitary Commission County Surveys in 1912, by State

| Program Expenditures,a $ |

||||||

| By County | By RSC | County Rank in Expenditures | Infection Surveys,b No. of Counties | Entry Order Into Program | Hookworm Rates, %c | |

| North Carolina | 8 355 | 19 153 | 1 | 33 | 2 | 42.8 |

| Mississippi | 3 875 | 19 611 | 2 | 26 | 7 | 39.9 |

| Georgia | 2 618 | 15 726 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 65.7 |

| Kentucky | 1 700 | 14 823 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 27.2 |

| Alabama | 1 475 | 12 136 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 48.9 |

| Louisiana | 1 463 | 14 260 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 27.0 |

| Texas | 1 060 | 4 118 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 29.1 |

| Tennessee | 772 | 16 514 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 30.4 |

| South Carolina | 600 | 14 087 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 53.4 |

| Virginia | 500 | 13 637 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 22.6 |

| Arkansas | 64 | 13 243 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 24.8 |

Source. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Third Annual Report 1912, Table 10, p. 27.

Source. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Third Annual Report 1912, Table 1, p. 21.

Rates are calculated for the entire set of counties (1911–1914).

The RSC may have supported enthusiastic counties because of their potential to generate—from below—public pressure for treatment. Such pressure also might motivate county officials to improve sanitation and advance the RSC’s primary goal, to eradicate infection by eliminating soil pollution.58 Stiles recalled that at medical meetings,

One favorite expression was to the effect that the eradication of hookworm disease should be based upon “20 per cent. thymol and epsom salts [treatment] combined with 80 per cent. sanitation [prevention].”59

The commission also may have favored the enlistment of sympathetic counties because of an additional concern in light of a goal of eradication: economic efficiency.60 The commission understood the economic importance of cultivating local monetary support:

[A]ppropriation of county funds by the county commissioners carries with it a moral weight which no appropriation of money from the outside could have.”61

If such program effects occurred, the odds of a county’s inclusion in the RSC sample would be higher in progressive counties with higher rates of school attendance and in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Georgia—states with counties that had been early to adopt expenditures and activities for the local RSC programs.

Commission members, from the start, cultivated the goodwill and support of Southern elites to promote project goals.62 Consistent with a vertical public health project design, the RSC did not disturb established state or local social, economic, or political arrangements and avoided a broad, horizontal sweep to fix widespread health problems of the region. Rather, they attempted a top-down reach into the South to fix a particular health problem—hookworm.63 For example, textile mills posed numerous serious public health risks: lung disease, hearing loss, and other infectious diseases. Yet Stiles refused to publicly blame mill work or mill owners for the general poor health of workers. He instead attempted to marshal owners’ support by providing information about monetary losses in mill productivity due to hookworm.64 His recommendation that mill clean up be limited to privies, and then only on a voluntary basis, angered social workers, child labor activists, and progressives of the time.65

Mill towns were undergoing economic development and urbanization, and the RSC needed counties with such resources for project support; few other Southern counties could afford this.66 However, greater RSC participation by industrial or rapidly developing counties presented a public health contradiction, in that hookworm was a rural disease and most prevalent in areas lacking development. (This does not preclude its high prevalence in mines or mills because of their special environments.) It also represented a programmatic health contradiction, for if eradication or even control was a goal, the RSC could not ignore subpopulations that were less accessible or less motivated to visit dispensaries; all needed to be reached.67 But it may have been the case that populated or industrializing counties actually were less likely to be in the RSC sample, declining to participate because of concerns about development; they risked being labeled as places with hookworm problems. An Alabama state operative noted,

[S]everal times … letters from “abroad” [asked] if it would be advisable to come to certain places in Alabama to live and make certain investments, where hookworm disease prevailed.68

To determine why RSC counties were included in the hookworm survey, we statistically examined, in a two-stage procedure, county selectivity in participation and hookworm infection rates. We expected to find that counties in the RSC sample had a greater environmental risk of hookworm, as measured by climate, elevation, and soil type. A more critical issue was whether county participation strongly reflected local recruitment effects, as measured by early program adoption, progressivism in school attendance, and economic development (number of textile mills). We expected county hookworm prevalence rates in sampled counties to be higher where environmental risks, soil pollution as measured by a sanitation index, and unimproved land supported the life cycle of the worm. We also expected higher rates in counties with smaller populations, lower population densities, and less economic growth (number of textile mills). A final critical issue was whether hookworm prevalence rates reflected project effects, measured as the year of RSC sampling. We adjusted, in both equations, for the percentage of the county population that was Black.

DATA AND VARIABLES

We obtained county-level expenditures, by state, on hookworm-related activities, county-level hookworm prevalence rates, and sanitary indexes from the RSC’s Annual Reports (1910–1912, 1914–1915). The hookworm rates, compiled by the RSC, were based on the microscopic examination of ova in the stool samples of randomly selected rural children aged 6 to 18 years (tested regardless of physical appearance) in nearly 600 counties from 1911 to 1914. The variable “sanitary index” was based on RSC surveys determining the level of county sanitation by tabulating types of latrines in more than 600 counties. At least 100 rural homes were examined in a county; counties were then ranked on a scale from 0 (worst level) to 100 (best level).69 Our total sample includes 984 counties.70

We obtained county-level data from the 1910 and 1920 US Census.71 For counties formed after 1910, county data from 1920 fill in missing values of variables. We obtained the number of county textile mills from a historical directory of textile mills that lists mills by town or city.72 We determined which counties the mill towns were located in via US Census tables. We obtained soil data from the US Department of Agriculture.73 The variable “particle size” is the average soil separates (i.e., different ranges of the diameters of particles) for a county; it is a measure of the size of the particles making up the top surface of the soil in a county. We calculated it as the weighted average of the soil separates for the top surface of the soil in all map units (soil survey areas containing the same soil type) located within a given county, where the weight is the percentage of the county’s total acreage in each map unit. The source of the variable “elevation” is also the US Department of Agriculture soil survey. Elevation is the vertical distance (in meters) from mean sea level to a point on the earth’s surface in a given county.

We gathered climate data from annual state climatology reports for the years 1906 through 1914.74 We constructed county-level average climate indicators by using the arithmetic means of all local weather stations located within a county, with the climate variables calculated from the year the initial county hookworm survey was performed. The variable “precipitation” is the average, in inches, of the annual total precipitation in a county in the five years prior to the county’s hookworm survey year. The variable “temperature” is the average, in degrees Fahrenheit, of the annual mean temperatures in a county in the five years prior to a county’s hookworm survey year. For counties without a hookworm survey, we used the average hookworm survey year (1913) as the base year. The variable “year of RSC infection survey” (ranging from 1911–1914) is the year a participating county was sampled.

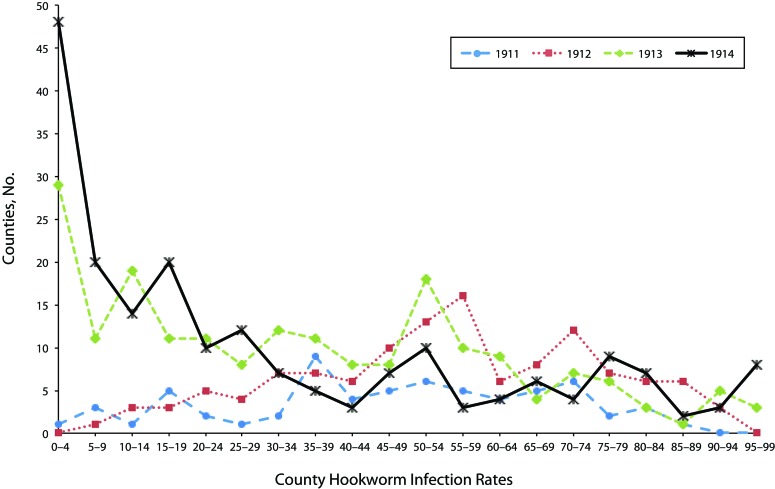

Figure 1 shows the distribution of hookworm infection prevalence rates in sampled counties (horizontal axis) by the number of counties (vertical axis) with given rates by year. By 1913, with the dispensaries in full force, county sampling distributions shifted to those with relatively lower prevalence rates; nearly 50% of counties the RSC sampled in 1914 had rates of hookworm infection of 20% or less.

FIGURE 1—

Distribution of county hookworm infection rates by year sampled.

Except for mills and year of survey, we used multiple imputation on the database for missing observations; reported variables and their descriptive statistics are the averages from 20 different imputed data sets with randomly imputed values for missing data and the observed values in the climate, soil, and RSC hookworm and sanitary index. We generated the imputed data with the MI procedure in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Infection rates in Tables 1 and 2 are based on the full data set with observed and imputed data.

TABLE 2—

Descriptive Statistics of Southern Counties Sampled for Hookworm by the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission (RSC), 1911–1914

| Dependent Variable | Mean or Proportion (SD) |

| County in RSC sample, % | 59.40 |

| County hookworm infection rate, % | 38.40 (25.72) |

| Proportion of RSC-participating counties, by state | |

| Alabama | 0.06 |

| Arkansas | 0.08 |

| Georgia | 0.12 |

| Kentucky | 0.04 |

| Louisiana | 0.09 |

| Mississippi | 0.13 |

| North Carolina | 0.17 |

| South Carolina | 0.05 |

| Tennessee | 0.10 |

| Texas | 0.05 |

| Virginia | 0.10 |

| Total | 1.0 |

| County-level environmental characteristics | |

| Frost-free d/y | 219.73 (36.46) |

| Particle size, cm | 0.15 (0.06) |

| Temperature, °F (5-y average of annual means) | 61.78 (4.12) |

| Precipitation, in (5-y average of annual totals) | 47.93 (7.56) |

| Elevation, meters | 163.73 (153.82) |

| County-level population characteristics | |

| Proportion Black | 0.33 (0.24) |

| Population/mile2 | 51.11 (74.29) |

| Population | 22 616.24 (21 625.40) |

| County-level program effects | |

| Proportion of children attending school | 0.57 (0.08) |

| Counties in early-adopting states | 34.2 |

| No. of mills | 1.07 (3.24) |

| Year of RSC infection survey | 1912.90 (0.99) |

| County-level soil pollution risk | |

| Sanitary index | 7.01 (5.73) |

| Improved acreage | 112 104.22 (67 782.26) |

Note. Total may not total 1.0 because of rounding.

STATISTICAL RESULTS

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2. The RSC sampled children in 59.4 % of Southern counties in the 11 participating states. More than one in three children had hookworm infection as indicated by laboratory tests of stool samples; the mean county prevalence rate was about 38%. County sanitation was poor to nonexistent; a home with no privy received a score of zero and a home with a water closet connected to a sewer received a score of 100. The mean county sanitary index of 7.01 suggests that at least half of homes surveyed by the RSC had no privy at all, and most of the rest had facilities unconnected to sewers.

Table 3 presents a two-stage selection model; stage 1 results were obtained by logistic regression, to predict a Southern county’s odds of inclusion in the infection survey sample. The second stage in Table 3 reports the results of an ordinary least squares regression of infection rates on the variables from sampled counties.

TABLE 3—

Two-Stage Selection Model of Rockefeller Sanitary Commission’s Sampled Counties and Reported Hookworm Rates in the Counties Sampled, 1911–1914

| Stage 1: Odds That County Is in RSC Sample,OR (95% CI) | Stage 2: Hookworm Infection Rate,b (SE) | |

| State (Ref: Virginia) | ||

| Alabama | … | 1.47 (4.97) |

| Arkansas | … | 2.28 (4.73) |

| Georgia | … | 18.07*** (5.04) |

| Kentucky | … | 29.44*** (5.13) |

| Louisiana | … | 13.70* (6.01) |

| Mississippi | … | 11.88 (6.53) |

| North Carolina | … | 5.98 (4.56) |

| South Carolina | … | 3.31 (5.08) |

| Tennessee | … | 26.08* (3.98) |

| Texas | … | 4.90 (6.23) |

| Environmental characteristics | ||

| Frost-free, d | 1.004 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.16** (0.05) |

| Particle size | 0.04* (0.003, 0.70) | 310.94*** (21.94) |

| Temperature | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | 0.58* (0.30) |

| Precipitation | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.06) | −0.04 (0.15) |

| Elevation | … | −0.002 (0.007) |

| Population characteristics | ||

| Proportion Black | 2.70* (1.20, 6.07) | −11.30* (4.42) |

| Log population density | 6.65* (1.19, 37.1) | −10.20** (3.59) |

| Log population density squared | 0.64*** (0.51, 0.82) | … |

| Log population | 2.37*** (1.72, 3.25) | 7.30* (3.01) |

| Program effects | ||

| Log school attendance | 7.36** (2.25, 24.1) | … |

| County in early adopter state | 2.41*** (1.62, 3.58) | … |

| No. of mills (1913) | 1.12** (1.03, 1.21) | −0.98*** (0.25) |

| Year of RSC infection survey | … | −5.46*** (0.76) |

| Soil pollution risk | ||

| Sanitary index | … | −0.64*** (0.16) |

| Log improved acreage | … | −8.01*** (1.50) |

| Intercept | … | 88.87** (28.63) |

| Hazard | … | 8.47 (11.70) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; RSC = Rockefeller Sanitary Commission. For stage 1, n = 984; c2 = 200.22; df = 11. For stage 2, n = 584; adjusted R2 = 0.63.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Stage 1 in Table 3 shows that a county’s probability of being in the RSC sample only partly reflected environmental factors maintaining the life cycle of the worm; counties with greater precipitation were more likely to be sampled than others, but counties with greater particle size (or sandier soils) were less likely. Counties with a greater proportion of Black residents had higher likelihoods of being sampled.

Findings also hint at an RSC tradeoff of different kinds of project goals or efficiencies. A nonlinear population density pattern of inclusion (inverted U) indicates that counties least likely to be sampled—hence less involved in the public health project—were those with the least and most dense populations. Residents in the former were presumably at greater risk of hookworm exposure and also needed diagnosis, treatment, and long-term intervention. Counties with larger populations and somewhat greater population densities, which were more likely to be sampled, may have had lower risk but might have been better able to contribute resources to the public health effort and boost the official numbers screened in dispensary activities. The boosting of numbers turned out to be important to the RSC; dispensary tallies were highlighted in the published Annual Reports. In other program effects, higher school attendance rates and county location in early program adopter states increased the odds of a county being present in the RSC sample. Finally, counties undergoing economic growth, as indicated by mills, were more likely to be in the RSC sample.

Stage 2 in Table 3 models hookworm infection rates in sampled counties. Environmental conditions, such as frost-free days, soil type (particle size), and mean temperature are significantly associated with increased hookworm prevalence rates. Sanitation level, a causal factor for hookworm in the eyes of RSC germ theorists, and related land improvement, were inversely associated with rates, as also expected. Counties with a higher proportion of Black residents had significantly lower hookworm rates, accounting for their greater county likelihood of selection (stage 1).

Sampled counties with more textile mills had significantly lower infection rates. It may be, as Stiles suggested, that Southern economic development marginally improved public health—at least with regard to hookworm prevalence—but, perhaps in a “healthy migrant effect,” the sickest rural residents did not move to mills or urbanizing areas. Greater county population was associated with higher infection rates, whereas population density was associated with lower ones. A polynomial term, for density squared, was not significant and not included in this model. After adjustment for timing of entry into the project, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Tennessee had significantly higher rates than Virginia, which had the lowest rates.

Local program effects were significant. Counties sampled in the later years of the project, after the dispensary model had taken hold, had significantly lower rates. It is unlikely that lower rates reflected public health activities elsewhere in the South or county efforts prior to or during the RSC sampling process; lowering rates took considerable time and, above all, treatment and improved sanitation. It is more likely that, because of the economic and population-based selection factors noted earlier in this section, the characteristics of the sampled counties changed over time. Counties sampled later in the project had, on average, lower infection rates; this suggests that actual Southern hookworm rates may have been higher than heretofore estimated with RSC data.

CONCLUSIONS

The nature of the Southern cotton economy both reflected and produced regional differences in economic development and disease structure and, more generally, a distinctive South. In this context, the RSC, a Northern philanthropy, focused on one condition, hookworm infection, with goals of mapping regional prevalence, treatment, and eradication. To this end, trained parasitologist Stiles and RSC administrators coordinated with Southern state boards of health for state agents to make local assessments of need and to provide screening and treatment and improvements in sanitation.75 But the public, members of the press, and even Southern medical practitioners rejected RSC insinuations that they and community neighbors were likely to be infected by worms and needed testing, treatment, and privies. Changing tactics, the RSC adopted public dispensaries to attract, educate, and organize local publics and, to some degree, shift local as well as state resources toward fulfilling RSC project goals. The commission learned that counties could be better units than states for administrating public health.

But strategic change had consequences. We find that the likelihood of a Southern county’s inclusion in the RSC infection survey and participation in the program not only reflected local environmental disease risk but population social characteristics and project implementation effects. RSC-sampled counties had considerably greater population densities, higher school attendance rates, and more textile mills than nonsampled counties. Yet these types of counties had, on average, lower infection rates. In other words, rural, less-developed counties with greater hookworm prevalence and treatment needs saw significantly less RSC involvement. In addition, counties with a higher proportion of Black residents were more likely to be sampled even though hookworm prevalence and disease severity was lower in the Black than in the White population. This pattern likely represented White concern about Black disease transmission among the Southern elites drawn to local programs; few of the dollars directed to these counties were channeled to Black residents to improve their health.76

It is important that greater RSC sampling selectivity over time represents a substantive process. Dispensaries generated local enthusiasm and resources that furthered program reach although other at-risk counties were not able or inclined to participate. As the project increasingly engaged urbanizing, progressive counties and shifted program goals toward public demonstrations in dispensaries, many at-risk counties were systematically lost to screening. Treatment and the goal of eradication or complete elimination of the disease could not be advanced. Even a lesser public health goal of disease control could not be advanced, for it required public health support of low-resource, rural counties.

Stiles, who trained in Europe, and Rose, who visited Puerto Rico, were well aware of hookworm eradication in European mines and of significant hookworm control in Puerto Rico.77 Their writings suggested that control and even the difficult goal of eradication were possible. But although the RSC initially proposed eradication, it limited the funds to be expended and the time for work to be done. In the end, whatever the intent, resistance to project continuation soon emerged from the RSC leadership itself. Even as the project was rolled out in early 1910, Rose and others were collecting data on hookworm on site elsewhere in the world. From the very first Annual Report, the commission mapped international hookworm prevalence, calculating economic productivity losses, country by country, caused by the disease. From 1913 onward, the Rockefeller Foundation shifted hookworm eradication efforts to a new International Health Board (IHB) that worked globally, although it still included the US South after the RSC ended in 1914. Recognizing that dispensaries had not led to prevention, the IHB soon promoted county-level intensive screening with sanitation reform. A follow-up IHB hookworm resurvey on a small subsample of previously screened Southern counties in the early1920s found steep declines in infection rates compared with rates in the years 1909 to 1914. On the basis of these findings, the IHB claimed in 1927 that the worm had indeed been eradicated in the region. This was not quite true; occasional public health studies detailing hookworm in the South continued at least until the 1970s.78 By 1914, however, the RSC project had turned an important corner: it extended the reach of public health even though it soon departed from the South. It would take a bit longer for Southern public health efforts to take root.

Acknowledgments

R. A. McGuire received support for part of the research contained in this article from the National Science Foundation (grants 0003342 and 0721000), Ohio Board of Regents (Individual Research Challenge Match, 1999–2001 and 2007–2009 Biennia), and The University of Akron (Faculty Research Grant, 2004).

This article was presented at the 108th annual meeting of the American Sociological Association; August 10–13; New York, NY.

Gregory J. Madonia and Robert A. McGuire created the disease, climate, soil, and demographic database used in this article. We thank the Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, NY, for permission to access its holdings and use its materials. We also thank Jessica Collins Andrew Dahlem, Nicholas Fritsch, Lisa Mishne, and Rui Pan for their assistance with data collection.

Note. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, Ohio Board of Regents, or The University of Akron.

Endnotes

- 1. John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 35.

- 2. Charles W. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric, of the Hookworm (Uncinariasis) Campaign in Our Southern United States,” Journal of Parasitology 25 (1939): 283–308.

- 3. Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Ralph W. Nauss, “Hookworm in California Gold Mines,” paper presented at the American Public Health Association, San Francisco, CA, 1920.

- 6. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 7. C. F. A. Bruyning, “Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Helminths in Human Populations,” in Chemotherapy of Gastrointestinal Helminths, ed. H. VandenBossche, D. Thienpont, and G. Janssens (Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1985), 7–66; Nauss, “Hookworm in California Gold Mines.”.

- 8. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 9. Alan Marcus, “The South’s Native Foreigners: Hookworm as a Factor in Southern Distinctiveness,” in Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, ed. Todd L. Savitt and James Harvey Young (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1991), 79–99; Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 10. Ettling, Germ of Laziness; Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 11. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease, Fifth Annual Report, for the Year 1914 (Washington, DC: Offices of the Commission, 1915), 12–13, http://archive.org/details/cu31924005710839 (accessed August 1, 2011)

- 12. Nancy Stepan, “The National and the International in Public Health: Carlos Chagas and the Rockefeller Foundation in Brazil, 1917–1930s,” Hispanic American Historical Review 91 (2011): 469–502.

- 13. Edward H. Beardsley, A History of Neglect (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1990); James Breeden, “Disease as a Factor in Southern Distinctiveness,” in Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, ed. Todd L. Savitt and James Harvey Young (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1991), 1–28.

- 14. Gilbert C. Fite, Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture 1865–1980 (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1984); Gavin Wright, Old South New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1986)

- 15. John A. Ferrell, Hookworm Disease (Raleigh, NC: Edwards and Broughton Printing Company, 1913), 3.

- 16. Joseph H. White, Underground Latrines for Mines, Technical Paper 132 (Washington, DC: Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1916)

- 17. Celia V. Holland and Malcolm W. Kennedy, The Geohelminths: Ascaris, Trichuris and Hookworm (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002)

- 18. Holland and Kennedy, Geohelminths; M. L. H. Mabaso, C. C. Appleton, J. C. Hughes, and E. Gouws, “Hookworm (Necator Americanus) Transmission in Inland Areas of Sandy Soils in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa,” Tropical Medicine & International Health 9 (2004): 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Charles W. Stiles, “The Surface Privy as a Factor in Soil Pollution, With Resulting Hookworm Disease and Typhoid Fever,” Public Health Reports 24 (1909): 1445–1447.

- 20. Beardsley, A History of Neglect.

- 21. “Putting a Stop to Soil Pollution: Results of Sanitary Survey,” Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease Records, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 34, Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, NY, undated. To research this article, one of the authors, R.A. McGuire, visited the Rockefeller Archive Center (hereafter RAC) to examine materials contained in the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease Archives (hereafter RSC) and the Rockefeller Foundation Archives (hereafter RFA), both of which are housed within the RAC. The primary records examined in the Sanitary Commission Archives were the commission’s five Annual Reports (1910–1912, 1914-1915) and all materials contained in Series I and II of the records. The primary records examined in the Foundation Archives were those related to hookworm in Record Group 5, the International Health Board, but Record Groups 1, 3, and 6 were also examined for materials related to hookworm in the American South.

- 22. Beardsley, A History of Neglect; Allen Tullos, Habits of Industry: White Culture and the Transformation of the Carolina Piedmont (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1989)

- 23. Tullos, Habits of Industry.

- 24. Cheryl Elman and George C. Myers, “Geographic Morbidity Differentials in the Late Nineteenth Century United States,” Demography 36 (1999): 429–443. [PubMed]

- 25. Beardsley, A History of Neglect.

- 26. Charles W. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease Among Cotton-Mill Operatives,” Report on Condition of Women and Child Wage-Earners in the United States, Volume XVII (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912)

- 27. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease Among Cotton-Mill Operatives.”.

- 28. Beardsley, A History of Neglect; Stiles, “Hookworm Disease Among Cotton-Mill Operatives.”.

- 29. Beardsley, A History of Neglect.

- 30. Marcus, “The South’s Native Foreigners,” 82; Ettling, Germ of Laziness; Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 31. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric,” 297.

- 32. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease, Second Annual Report (Washington, DC: Offices of the Commission, 1911), http://archive.org/details/cu31924005710755 (accessed August 1, 2011)

- 33. Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 34. Charles A. Kofoid to Dr Meyer, January 6, 1919, RFA, International Health Board (hereafter IHB), Record Group 5, Series 2, Sub-Series 200, Box 3, Folder 18, RAC.

- 35. Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 36. Stephen J. Kunitz, “Explanations and Ideologies of Mortality Patterns,” Population and Development Review 13 (1987): 379–408.

- 37. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease, First Annual Report; Organization, Activities, and Results up to December 31, 1910 (Washington, DC: Offices of the Commission, 1910), 4, http://archive.org/details/cu31924005710755 (accessed August 1, 2011)

- 38. Kunitz, “Explanations and Ideologies,” 396.

- 39. Wickliffe Rose, “A Sanitary Survey,” American Journal of Public Health 3 (1913): 655–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, First Annual Report; Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 41. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, First Annual Report, 3.

- 42. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease Among Cotton-Mill Operatives.”.

- 43. Bruyning, “Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Helminths in Human Populations.”.

- 44. Holland and Kennedy, Geohelminths.

- 45. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, First Annual Report, 25.

- 46. Ibid, 26.

- 47. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Second Annual Report, 9.

- 48. Ibid, 18; Warwick Anderson, “Going Through the Motions: American Public Health and Colonial Mimicry,” American Literary History 14 (2002): 686–719. Anderson reports that Wickliffe Rose visited Dr Bailey Ashford’s hookworm treatment project in Puerto Rico in 1910. Using “dispensary fairs” and medical methods, Ashford had screened and treated nearly a quarter million people by the time of Rose’s visit in 1910. Rose, influenced by Ashford’s methods, likely took the dispensary idea back to the United States (Anderson, p. 701). Also see John A. Ferrell, “Hookworm Disease, Its Ravages Prevention and Cure,” Journal of the American Medical Association 25(1914): 1937–1944; Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric.”.

- 49. Benjamin E. Washburn, The Hookworm Campaign in Alamance County, North Carolina, State Board of Health Edition (Raleigh, NC: E. M. Uzzell and Company, 1914), 16.

- 50. Washburn, Hookworm Campaign in Alamance County.

- 51. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Second Annual Report, 26.

- 52. Charles W. Stiles, “Special Report on a Preliminary Survey of Texas,” RFA, IHB, Record Group 5 Series 2, Sub-Series 249, Box 19, Folder 109, Page 1, RAC, undated.

- 53. Charles W. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease in Its Relation to the Negro,” Public Health Reports 24 (1909): 1083–1089; Ferrell, Hookworm Disease; Mabaso et al., “Hookworm (Necator Americanus) Transmission in Inland Areas.”.

- 54. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease in Its Relation”; Philip R. P. Coelho and Robert A. McGuire, “African and European Bound Labor in the British New World: The Biological Consequences of Economic Choices,” Journal of Economic History 57 (1997): 83–115; Philip R. P. Coelho and Robert A. McGuire, “Racial Differences in Disease Susceptibilities: Intestinal Worm Infections in the Early Twentieth-Century American South,” Social History of Medicine 19(2006): 461–482; Robert A. McGuire and Philip R. P. Coelho, Parasites, Pathogens, and Progress: Diseases and Economic Development (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011)

- 55. Charles W. Stiles, Soil Pollution as a Cause of Ground-Itch, Hookworm Disease (Ground-Itch Anemia) and Dirt Eating (Washington, DC: Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, 1910), 11.

- 56. “Report on Work for the Relief and Control of Uncinariasis in Southern United States,” RFA, IHB, Record Group 5, Series 2, Sub-Series 200, Box 1, Folder 2a, RAC, 1915.

- 57. Beardsley, A History of Neglect; Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 58. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, First Annual Report; Wickliffe Rose, “A Sanitary Survey.”.

- 59. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric,” 297.

- 60. Kunitz, “Explanations and Ideologies.”.

- 61. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Second Annual Report, 19.

- 62. Beardsley, A History of Neglect; Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 63. Kunitz, “Explanations and Ideologies.”.

- 64. Stiles, “Hookworm Disease Among Cotton-Mill Operatives.”.

- 65. Beardsley, A History of Neglect.

- 66. Ettling, Germ of Laziness.

- 67. Kunitz, “Explanations and Ideologies,” 395.

- 68. William Dinsmore to Wickliffe Rose, January 5, 1912, RSC, Series 2, Box 4, Folder 79, RAC.

- 69. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Second Annual Report, 24–25.

- 70. All counties in 10 of the 11 Southern states in the RSC project, and only the eastern counties in Texas.

- 71. Michael R. Haines and Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data: The United States, 1790–2002 [computer file] (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, distributor)

- 72. Official American Textile Directory 1912–1913 (Boston, MA: Lord & Nagle Company, 1913)

- 73. US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, “Soil Survey Spatial and Tabular Data (SSURGO 2.2),” http://datagateway.nrcs.usda.gov (accessed August 8, 2013)

- 74. US Department of Agriculture, “Climatological Service of the Weather Bureau, Annual Summary,” 1906–1914 (citation changed to US Department of Agriculture, Weather Bureau, “Climatological Data, Annual Summary” or “Climatological Data” in 1913 or 1914 depending on the state), http://www7.ncdc.noaa.gov/IPS/cd/cd.html (accessed August 8, 2013)

- 75. Wickliffe Rose, State Systems of Public Health in Twelve Southern States (Washington, DC: Judd and Detweiler Inc., 1911)

- 76. Beardsley, A History of Neglect.

- 77. Anderson, “Going Through the Motions,” 701; Ferrell, “Hookworm Disease, Its Ravages Prevention and Cure.”.

- 78. Alvin E. Keller, W. S. Leathers, and Paul M. Densen, “The Results of Recent Studies of Hookworm in Eight Southern States,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine 20 (1940): 493–509; Larry K. Martin, “Hookworm in Georgia: Survey of Intestinal Helminth Infections and Anemia in Rural School Children,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 21(1972): 919–929. [PubMed]