Abstract

I reexamine the notion of public health after reviewing critiques of the prevalent individualistic conception of health. I argue that public health should mean not only the health of the public but also health in the public and by the public, and I expound on the social contingency of health and highlight the importance of the interpersonal dimensions of health conditions and health promotion efforts. Promoting public health requires activating health-enhancing communicative behaviors (such as interpersonal advocacy and mutual responsibility taking) in addition to individual behavioral change. To facilitate such communicative behaviors, it is imperative to first construct a new discursive environment in which to think and talk about health in a language of interdependence and collective efforts.

What is this mysterious “public health?” Can the “public” even have a “health?” Surely “health” applies to individuals; aren’t matters of individual “private” not “public?” The term seems almost an oxymoron.

– Christopher Hamlin1

Public health is a vision in practice. It inspires interdisciplinary scholarly endeavors and mobilizes broad-scoped institutional efforts. Yet it is also a notion largely taken for granted, wanting further explication. Hamlin’s question compels us to pause and ponder, What is public health? How can health be public?

Indeed, in our everyday understanding, health is an individual matter belonging to one’s private sphere. Whether in the sense of being free from disease or possessing some culturally defined desirable attribute such as white teeth or tanned skin, health designates an individual’s state of being. Health, in a descriptive sense, is an asset physically embodied in each individual self. Yet health is also a condition in flux. A healthful status could stay unchanged or be bettered; it could wane, be regained, or be permanently lost. Health, as an absent presence,2 is a rather precarious status quo disposed to imbalance. Analyzing health is to define the perpetrating conditions, attribute responsibility, and identify corresponding solutions. Different value-based and epistemological perspective takings underlie such analyses,3 resulting in different health promotion approaches. From such analytical lenses, the individual-based construal of health is rethought: Are health problems individual in nature? Is public health an oxymoron?

Starting with such reflections, I accentuate the social contingency of health, calling for attention to both the social conditions of and social solutions for health problems. On the basis of a critique of the prevalent individualistic conception of health, I first put forth a multilevel conceptual framework for analyzing health conditions. Through a review of relevant findings from the social network analysis literature, I then specifically focus on the power of interpersonal influence on health outcomes and argue for the importance of evoking communicative behaviors to build public health as a collective enterprise. To create a social environment that fosters such awareness of shared responsibilities, one core strategy is to reframe health issues by establishing a language of interdependence and collective efforts. By rethinking public health as the health of the public, in the public, and by the public, I hope to shed new light on health promotion efforts. In addition to promoting individual behavioral changes (e.g., “You should not binge drink”) that have traditionally been the focus of health communication campaigns, health-enhancing communicative behaviors should also be an important goal. Health promotion will benefit from increased efforts targeted at interpersonal advocacy (e.g., “Tell your friends not to binge drink”) and mutual responsibility taking (e.g., “Make sure your friends do not drive when they are drunk”).

HEALTH AS A MERE MATTER OF LIFESTYLE AND PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY

Personal responsibility, which is to say responsibility and enlightened behavior by each and every individual, truly is the key to good health… . We have become … increasingly appreciative of the extent to which our physical and emotional well being is dependent upon measures that only we, ourselves, can affect.4

The personal responsibility rhetoric of health has been dominant in the thinking and practice of public health. It resonates well with a repertoire of notions that our culture takes pride in—self-sufficiency, self-governance, free choice, individual independence, and the like. Undeniably, a direct link exists between overeating and obesity and smoking and lung cancer, for example, which puts individual actions and their health outcomes in one equation. In everyday thinking, health has by and large been interpreted as individual lifestyle, and personal responsibility has become the most popular, sanctionable prescription.

To a large extent, this individualistic conception is a product of sociocultural constructions over the past 3 to 4 decades. In their essay, Howell and Ingham5 eloquently discussed how individual lifestyle became the dominant language and ideology as a result of the changing political culture and growing market forces. Illness, health care, and unemployment in this era have all been “redefined as private issues of character—as a failure in individuals who refused to fight the good fight.”6 Media advertising, popular texts, and academic health discourse are all part of the successful discursive construction of individuals as “solely responsible for acquiring skills needed for personal well-being,”7 a belief that has become so pervasive and ingrained that it largely falls outside our reflective radar.

The problem with such individual-oriented constructions of health is that they fail to recognize the influence of social structures and surroundings on individuals’ health. There are upstream causes of health problems, including sociocultural, political, and environmental influences on individual health. Health can be an issue of political ideologies,8 socioeconomic stratification,9 social justice,10 and so forth. Societal conditions beyond individuals’ control can affect their health; hence, one’s risk of being put at risk is determined by a host of social factors.11 For example, one’s exposure to risk depends greatly on work conditions. An apparent lifestyle issue such as obesity is in fact indigenous to an environment saturated with fat-laden foods and limited access to physical outlets.12 The United States’ toxic food environment, Brownell claimed, is a significant cause of the rising obesity epidemic because individual susceptibility, “no matter how strong, will rarely create obesity in the absence of a bad environment.”13 Studies have also demonstrated that structural determinants such as socioeconomic status and neighborhood environment features, including residential environments of poor physical quality and less access to private transportation, are associated with people’s self-rated health conditions.14 In a more general and powerful depiction, Douglas and Wildavsky15 noted, “Some classes of people face greater risks than others … ; they would not accept them if they were rich or beautiful or nobly born.”

More specifically, the individualistic conception of health has been challenged on the grounds of epistemology, ethics, and praxis. Epistemologically, such an individualistic focus exclusively amplifies the role of human agency, without recognizing or acknowledging that human agency is often constrained by external social forces16 or that the very belief in personal agency and self-efficacy is shaped—debilitated or empowered—by the social and cultural fabrics in which individuals are placed. On the ethical front, the personal responsibility rhetoric, by suggesting an isolated causal connection between individual behaviors and health outcomes, fosters unfair perceptions of individual culpability17 and leads to victim blaming18 or victim stigmatizing.19 In practice, imputing health problems to individuals has negative implications for social movements vital to societal improvement.20 On one hand, it facilitates the marketing forces against healthy choices by deploying the logic of individual choice and freedom. For example, the sense of individual culpability cultivated by the current health discourse helps tobacco companies continue to expand their business while claiming no responsibility for their consumers.21 On the other hand, the individual responsibility rhetoric demobilizes public advocacy efforts because society is not seen as being at fault.22

From the individualistic viewpoint of health, public health simply means the health of the public, an aggregate-level, summative representation of individual health. Public health could be achieved, accordingly, when the malaise of individual conditions—ignorance, apathy, irresponsibility, lack of efficacy, and so forth—is removed. As the various streams of critical reflections reviewed earlier have contested, health should not be perceived as a mere matter of individual lifestyle and personal responsibility. Health, though individually possessed, is socially contingent. The social contingency of health requires that one understand health-related behaviors as being embedded in social contexts and devise changes on the basis of that understanding. Such a conception underscores the social conditions of and the social solutions for health problems. Public health, therefore, does not merely mean the health of the public but also health in the public and by the public. The public in public health, referring to more than just an aggregate of individuals, should also be understood as a substantive construct connoting (1) the sociotropic environment in which we exist, hence the mutual dependency of individuals on each other for health well-being (health in the public), and (2) the dynamic potentials of communicative acts by members of the public as the collective basis of sustainable health (health by the public).

HEALTH IN THE PUBLIC AND THE EXPLICATION OF THE HEALTH RISK SITUATION

There is great satisfaction in having some sense of control over one’s life. Our point is not to critique this but to locate such practices and their effects, despite their relative autonomy, into broader regimes of truth.23

Critiquing the individualistic conception of health is not to deny the importance of individual responsibility taking in health prevention. Rather, the point is to recognize the relative autonomy of individuals in health-risk situations and relocate individual health in broader regimes of factors so as to guide health promotion efforts with a more comprehensive, holistic picture.24

Health and Risk

The breadth of the concept of health seems to defy a definition. Attempts at it usually lead to something that is either too broad to delimit or too vague to denote. In her seminal work, Herzlich25 offered a fruitful set of conceptual representations of health: health in a vacuum, reserve of health, and equilibrium. “Health in a vacuum” defines health as a state of being free from illness. As such, health is a neutral condition that tends to be recognized when under the attack of illness. “Reserve of health” represents health as the capital asset or as potential capacity to resist illness. It is a quantified conception of health, because such capacity varies across individuals and may “increase or dissipate in the course of time.”26 “Equilibrium,” denoting health as subjectively experienced, more generally indexes one’s psychological well-being and felt control over life with sufficient social and physical resources.

Although equilibrium is regarded as “the superior form of health”27 and espoused as a more comprehensive definition of health,28 the second notion, reserve of health, is more pertinent to health promotion research. It describes, first of all, an objective conception of health, calibrated as the distance away from (potential) diseases. The primary intervention efforts in public health focus on improving individuals’ physical well-being through effective means of disease prevention and detection. Second, this conception captures the variable nature of health. Health is not a static state of being but a reserve that needs to be built up or else it could be used up. Health promotion, broadly defined as “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health,”29 ultimately aims at preserving and increasing individuals’ reserve, though often through different approaches.

The process of protecting the reserve of health from breaches and attenuation is one of minimizing health risks. Risk has taken a central place in contemporary health discourse. “Health promotion,” in essence, “operates within a discourse of risk.”30 Defining a risk has both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The quantitative dimension involves identifying statistical patterns of the distribution of some adverse effects within certain populations, such as the rate of accidents among drunk drivers or the likelihood of lung cancer among smokers. The qualitative aspect involves an array of questions, such as What is the potential loss? Loss to whom and caused by what? Answers to these questions are often offered from multiple vantage points. The plurality of answers reflects the complexity of risk as “a phenomenon of multiple contingency.”31

A Health Risk Situation

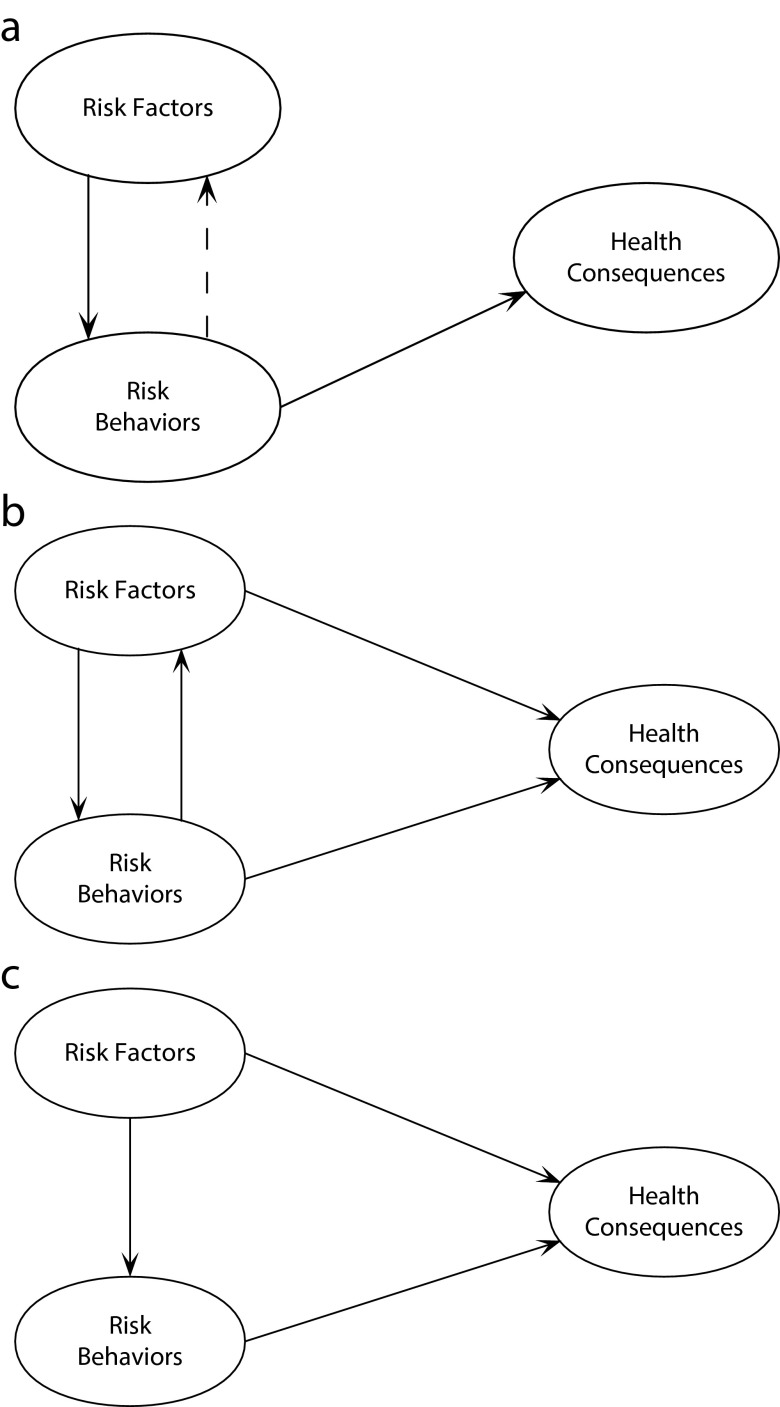

To provide a conceptual framework of the multiple contingency of health and risk, a health risk situation is constructed as an abstraction from possible problematic health situations (Figure 1). The goal is to offer a more holistic view of what makes individual actors prone to health hazards. Following Schulenberg et al.,32 I conceptually distinguish between 2 analytically separable parts of health-damaging causes. Health risk behaviors refer to individuals’ actions (e.g., binge drinking) or nonactions (e.g., not using a condom during sex) that have deleterious consequences for health.33 These are the proximal causes of health hazards. Health risk factors encompass conditions that incline individuals toward certain risk behaviors and predispose them to health consequences. As Figure 1 depicts, health risk factors can have direct bearing on one’s health consequences (e.g., air pollution and asthma) or on one’s risk behaviors (e.g., peer pressure and binge drinking). Distinguishing health risk behaviors and health risk factors at different levels contests the epistemic view of individuals as completely autonomous beings with full control over their behaviors. Individual behaviors are instead conceptualized as an endogenous factor within the broader social milieu.

FIGURE 1—

Conceptualizing health risk situation risk factors at the (a) individual level, (b) meso level, and (c) macro level.

Note. The dotted line refers to the potential feedback loop whereas the solid lines refer to the major force(s) of influence implied in each model.

In this framework, health risk factors are mapped onto multiple levels of analysis, including individual-level (or intrapersonal) factors such as knowledge, motivation, and efficacy beliefs; meso-level (or interpersonal) influences such as social norms and social networks; and macro-level forces such as working conditions, community resources, and public policies. A health risk situation for a given health phenomenon could be analyzed in terms of factors at all 3 levels (macro, meso, and individual). For example, causes of eating disorders can consist of individuals’ lack of awareness of the severe consequences (individual level), peer expectations and encouragement (meso level), and a media environment saturated with images exalting a thin ideal (macro level).

Individual-level factors.

The traditional health promotion approach gazes exclusively at individual-level risk factors and has been the implicit premise of most empirical studies that investigate designs and effects of health campaign messages. In a critical review, Dutta-Bergman34 pointed out that the guiding theoretical models used in health communication campaigns, including the health belief model,35 theory of reasoned action,36 and extended parallel process model,37 all highlight the primacy of individual determinants of risk behavior. Individual actors’ cognitive systems are regarded as the only genesis of their risk behaviors. The enactment of such behaviors may, in turn, function to reinforce the risk-prone cognitions, thereby forming a loop within the individual actor’s own cognitive–behavioral system38 (Figure 1a). The intervention efforts, accordingly, focus on changing individuals’ personal behaviors through alterations in their cognitive space. Health communication campaigns usually take on an educational module whereby health information blended with persuasive techniques is packaged and transferred to individuals.

Macro-level factors.

As discussed earlier, macro-level risk factors affect individuals’ health behaviors and conditions. They can include various constituents of the social infrastructure, such as socioeconomic status, community structures, institutional rules, public policies, and so forth. Such societal causes of health problems have been the focus of reflection and discussion among critical scholars of public health. They are structurally induced forces, externally imposed onto individuals (Figure 1c). Tracing health problems upstream to the macro-level causes, public health scholars and activists can focus on how to fix structural problems and supply or replenish resources needed by individuals. For example, the media advocacy approach seeks to advance public policy initiatives through strategic engagement of the media,39 and community-based intervention trials aim at mobilizing local organizations, improving community structure, or both.40

Meso-level factors.

Meso-level risk factors refer to the risk-predisposing influences that emanate from the very interconnectivity of individuals’ social existence and the interactions among these individuals. Broadly characterized, they encompass the “non-material aspects of the environment”—in particular, individuals’ everyday living along interpersonal dimensions.41 On one hand, humans’ coexistence in the same ecosystem means they pose health threats to one another, especially in cases of communicable diseases. The global scares of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003 or the H1N1 flu in 2010 were intensified by people’s awareness of their increased interconnectedness. On the other hand, social networks contribute to shaping and regulating individuals’ health-related behaviors with their reflexive attendance to various implicit rules and norms. For example, binge-drinking behaviors, a collegiate rite of passage, are partly a product of the sociocultural habitat indigenous to the college environment.42 The sizable literature on social norm has shown that perceived (and often misperceived) peer norms and peer pressure contribute significantly to risky behaviors.43

The sociotropic environment has a symbiotic relationship with the individuals who live under its influence while reconstituting it with their actions. As Lindheim and Syme pointed out,

The environment is a result of constant interaction between natural and man-made spatial forms, social processes, and relationships between individual and groups… . People are an essential part of the environment.44

Figure 1b shows this mutually constituting relationship. The sociotropic environment is made up of the ensemble of individuals’ activities, and yet it has global properties and influencing mechanisms that are not reducible to its constituting elements and thus is an independent source of influence at a higher level.45 As such, it is, and needs to be tackled as, an analytical target in its own right. To reshape the sociocultural environment regarding a health topic or health community requires, in addition to personal responsibility taking, communicative behaviors aimed at changing social norms and community culture. Such communicative behaviors may include information sharing, interpersonal health advocacy, mutual responsibility taking, and community participation. Through such behaviors, positive health beliefs and values get articulated more effectively and emphatically, and more health-enhancing elements can be built into the social environment.

The constructed health risk situation discussed in this section shows that individuals’ risk behaviors and health conditions are induced by risk factors at multiple levels. Epistemologically, individual behavior is conceptualized as an endogenous variable, a proximal but not the only cause of health consequences. Interventions at all 3 levels are needed in concerted efforts to solve the problem, and the differential weight of each level in constituting a specific phenomenon can be better pinpointed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of practical efforts. Communicative behaviors that aim at mutual information sharing and care taking, in addition to personal responsibility taking, should also be a focus of health promotion efforts. Public health also means health by the public.

HEALTH BY THE PUBLIC IS CONNECTED AND COMMUNICATED

A person’s risk of illness depends not merely on his own behavior and actions but on the behavior and actions of others, some of whom may be quite distant in the network.

People are more influenced by the people to whom they are directly tied than by imaginary connections to celebrities.46

Connected

The social network in which we reside is an intricate, powerful web of influences and risks. We are interconnected and thus interdependent. Whether we are aware of it or not, our health is constantly dependent on the goodwill of others around us. Consequences from other people’s behaviors ripple through this network as people find themselves involuntary victims of, for example, secondhand smoking or drunk driving.

In the same way in which diseases travel through the network, so too do health-related behaviors. Norms and behavioral imitation are 2 mechanisms enabling and facilitating the spread of health-related behaviors.47 The health communication literature has an abundance of evidence showing the effects of peer pressure or perceived peer norms in smoking initiation, excessive drinking, and distorted body image and consequent disordered eating behaviors. Social network research has shown that connection with others contributes to initiation and reinforcement of at-risk behaviors. A study by Christakis and Fowler48 demonstrated patterns of behavioral contagion in the spread of obesity in a network of 12 067 people over a period of 32 years. Having an obese friend increases an individual’s risk of obesity by 57%; having an obese sibling increases one’s chance of becoming obese by 40%; and having an obese spouse increases one’s risk of obesity by 37%.49

Yet, in the same way as such health-threatening behaviors exert their power of contagion and influence, health-enhancing behaviors can as well. These interpersonal dynamics can also be turned into a positive force. In another thorough analysis of network data, Christakis and Fowler50 demonstrated the rippling fashion in which smoking cessation occurred during a 32-year period. They observed that people quit smoking in groups, with remaining smokers marginalized and pushed to the peripherals of the larger social network. The likelihood of smoking cessation increases by 43% when a friend stops smoking, by 34% when a coworker in a small-sized company quits smoking, and by 67% when one’s spouse stops smoking. Another study showed that friends’ decisions to get a flu shot influence individuals. Specifically, when an additional 10% of friends receive a flu shot, an individual’s likelihood of getting a flu shot increases by 8.3%.51

Communicated

These findings point out the importance of interpersonal networks in promoting public health. With deliberate efforts by friends, family members, neighbors, coworkers, and other types of social relations to consciously spread health information and advocate healthy practices, it is possible to imagine that a cascade of health-enhancing behaviors can be induced through the network influence. Such communicative behaviors include information relay, interpersonal advocacy, and other participatory health-related behaviors for the purpose of fostering a more health-conducive environment.

Health promotion scholars and practitioners should make it a strategic focus to evoke such communicative awareness and behaviors among individuals, especially given that health promotional efforts have disproportionately focused on individuals’ personal health behaviors as the goal of change. Instead, communicative behaviors should be treated as an outcome variable in health communication research and intervention program designs. In other words, how to design messages that can activate positive interpersonal advocacy and communicative acts to promote health among individuals should be made an important empirical inquiry. Our messages to nonbinge drinkers in college, for example, should not only advocate personal restraint behaviors but also encourage them to spread information and speak to their drinking peers about the consequences of binge drinking. Vocalizing such values, beliefs, and attitudes can not only function as an additional information channel but also help shape positive perceptions about health values and social norms and, in the long run, build up a healthy community.

Such communicative behaviors can also facilitate desired structural changes at the macro level. The public opinion climate in which proposed health-enhancing policy changes are advocated, are evaluated, and get accepted, for example, consists of communication processes in which individuals develop and strengthen the awareness of health not as personal or private but as socially contingent. Moreover, advocating such communicative behaviors also reflects the normative value placed on civic engagement for improving public life. In the new public health discourse, community participation has been highlighted as among individuals’ civic duties, and taking responsibility for others is one of the defining elements of a healthy citizen.52 Cultivating communicative behaviors is among the first steps toward creating such healthy citizens.

This is, of course, easier said than done. The prevalent cultural belief that health is something personal and private is deeply ingrained. To effectively induce positive interpersonal communication about health, a more supportive discursive environment should first be developed and fortified. Health communication scholars and practitioners need to think about how to reframe health advocacy messages so as to reshape the public’s thinking about health as a collective enterprise and motivate them to participate more in promoting public health.

REFRAMING HEALTH FOR THE PUBLIC

Although this disconnect between public health theory and practice has several sources, … a significant cause is the fact that a language to properly express the unique public health approach has not been adequately developed.53

Wallack and Lawrence54 argued that the primary vocabulary for the public to think and talk about health is still one of individualism, which is deeply ingrained as “the first language of American culture.” The dominance of this language and its underlying value orientation makes it difficult for the public health approach to resonate with the public. Public health as a collective enterprise cannot fully advance its agenda without first creating in the public’s mind a repertoire of ideas and terms regarding connectedness and collective efforts.

Building such a repertoire is a process of (re)constructing the discursive environment in the domain of health in public life. When Wallack and Lawrence55 advocated developing the United States’ “second language”—a language of “interdependence and community” and “egalitarian and humanitarian values”—to effectively talk about public health and shape public health policies, what they envisaged was a discursive environment with a system of symbolic elements that articulated the values and ideas endemic to public health logic. Such discursive representations were to be constructed and communicated to the public, who would then internalize them as the lens through which to perceive health problems and the principles to guide their actions.

Broadly speaking, this is a social construction process in which public health researchers foster a discursive environment that in turn shapes the thoughts and actions of the individuals therein. Framing is core to this process. Although framing as a research field has been characterized as a fractured paradigm,56 all studies try to capture, from various perspectives, how social actors understand and structure (inwardly or outwardly) a certain social reality through an interpretive scheme.57 Framing, broadly construed, depicts how various social actors in specific sociocognitive contexts participate in constructing social realities. For example, framing research has examined how members of the public as social actors organize various aspects of their own life world (such as forming political attitudes and value judgments58) with the aid of interpretive frameworks embedded in media messages. Studies have also shown how members of the public actively and strategically engage themselves in public affairs by using symbolic resources to understand public issues,59 coordinate collective actions,60 and participate in public deliberation.61 Framing, therefore, offers a rather broad and integrative perspective on how public life is constructed, in and through a sociocognitive process in which cognition, discourse, and practice play out in a dynamic way.

In this social construction process, the role of public health scholars is no longer just that of health educators relaying relevant health information but also of social constructionists advancing frames of thinking to guide the public in terms of how to think about a health problem. Thus far, most theoretical references to and usage of framing in the health communication literature fall into Kahneman and Tversky’s62 tradition, following the gain-versus-loss framing effect on the adoption of prevention and detection behaviors.63 The goal of such framing is to increase the persuasive effectiveness of a specific health advocacy message. To establish a second language of health as Wallack and Lawrence advocated, however, requires that public health scholars approach framing as a social (re)construction process, one that restructures individuals’ thinking about health—from an individualistic conception about health to that of social contingency, interdependency, communal endeavor, and collective efforts.

In imparting a conception of health as interdependent, public health scholars are “frame entrepreneurs”64 engaged in the production of meaning in the interest of promoting their collective agenda. One way to fulfill this role is to create and keep pushing conversations with media professionals and the public about societal influences on health. Several content analysis studies have found, for example, that the dominant frame in media coverage on obesity is still one of individual responsibility, whether it is in TV, newspapers, or YouTube.65 The encouraging news, though, is that there has been a growing trend of references to societal causes in media coverage,66 partly as a result of scholarly work by public health experts.67 Another way is to intentionally use societal frames in health campaign messages. A societal frame of a health issue should discuss the social dimensions of health conditions and emphasize collective responsibilities as solutions. Because this is yet not a common message strategy, some exploratory efforts are needed to create such messages and test their effects. Empirical studies on health communication and persuasion, for example, could explore the effectiveness of a societal frame of health issues in comparison with the typical individual frame. Message strategies that aim to induce more communicative awareness regarding health and encourage individuals to undertake concerted efforts to improve public health, if pretested as effective, should be adopted and deployed more in health communication campaigns.

CONCLUSIONS

The popular, individualistic conception of health problematizes health conditions as residing in individuals’ private realm. From an individualistic viewpoint, public health is simply equated to health of the public in the aggregated sense. On the basis of extant critiques of this individualistic conception, I accentuated that health is socially contingent and health promotion is a collective enterprise.

The conceptual construction of a health risk situation is an attempt to systematically map out the factors at different levels that predispose an individual’s at-risk behaviors. A caveat is that these different levels are not mutually exclusive. Emphasizing this point cautions against the danger of a public health rhetoric that, in effect, turns value-based talk against meaningful practice. The tendency is, in thinking and talking in the public health discourse, to pit individuals against society in assigning responsibility. Some critiques of the individualistic conception of health sound like a broad-brushed dismissal of individual-level health intervention. For example, remarks such as the following are not uncommon:

Any approach to health promotion that concentrates on telling people not to smoke rather than placing constraints on the tobacco industry must be serving the interests of capital rather than authentically pursuing good health.68

Although correctly targeting the tobacco industry for its share of blame, such critiques are not entirely defendable. Telling people not to smoke does not contradict placing constraints on the tobacco industry, both of which are important and authentic approaches to pursue for good health. Kunitz69 labeled those who espouse individual responsibility versus societal responsibility as, respectively, voluntarists and determinists. Both parties see only part of the spectrum of health problems. The role of public health researcher should be primarily that of a problem solver who seeks to tackle all sources of the problems. Voluntarists see the societal aspects as out of the range of the health promotion task, whereas determinists free themselves from the duty of changing individuals. Problem solvers, by contrast, should diagnose problems and treat all sources of the problem as part of the solution.

Inducing communicative health-related behaviors is an important path for public health scholars to consider. Increasing positive interpersonal communication about the importance of healthy practices and preventive behaviors should be a goal of health communication campaigns. So far, few campaigns have taken this approach. An exception is the “friends don’t let friends drive drunk” campaign, the central message of which that individuals should encourage friends not to drive drunk and intervene when necessary so as to prevent possible accidents. The campaign has been a success: research has found that 62% of the audience exposed to the campaign ads have stopped others from driving drunk. In addition, given the prevalence of social media as a communication tool, especially among younger populations, health communication campaigns should also capitalize on its capacity for health information sharing within and across networks of individuals. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has offered social media tools for the campaign on obesity, aiming to amplify conversations on this issue through the platform of social media.70

While calling for more health communication campaigns with such interpersonal-oriented goals and strategies, we also recognize the difficulties in practice. Individualism has been one of the habits of the heart deeply ingrained in the American way of life,71 and health is often regarded as a private and taboo topic in social interactions. Wallack and Lawrence72 have lamented the difficulty in articulating the value of communal efforts and mutual responsibility taking to the public, especially with regard to health issues. It will take a long time to establish a second language for public health, one that values interconnection in a society and collective efforts and supersedes the first language of individualism. I propose that health communication scholars use framing as a strategy to reshape public understanding of health and be creative in inventing and examining new frames in communicating about health.

Undertaking such a task is challenging, but not mission impossible. Building an active interpersonal environment with collective value in health and mutual responsibility taking could facilitate potential infrastructure changes. As people become aware of the mutual contingency of health conditions, for example, they may demand and support policy changes to protect their health environment. Enforcement of a beneficial health policy would lead to positive changes in social norms, which would in turn help lift barriers in interpersonal communication about health topics (e.g., suggesting that a friend quit smoking would seem less offensive in a city that has regulations against smoking in public areas). In this sense, fostering a positive social–interpersonal environment should have long-term, cyclical benefits over time. Furthermore, the dialogic process, consisting of interpersonal conversations about information sharing and value articulation, is in itself a framing process in which meaning is constructed in conversational dynamics.73

Another note to add here regards the value of social network analysis to health communication literature. Research by network analysts such as Christakis and Fowler has shown that interpersonal networks can be both a curse and a blessing to public health. Recognizing the double-edged sword of the social network points to the importance of optimizing interpersonal influences to curtail communicable diseases and at-risk behaviors on the one hand and increase positive, health-enhancing behaviors on the other. Tactically, social network analysts recommend understanding the structural properties of a network and identifying the centrally located hub to best allocate resources. Health communication scholars and practitioners may make use of such knowledge and strategically select where to disseminate persuasive messages so as to achieve the best reach and influence.

In closing, let us return to the opening question posed by Hamlin.74 The term public health is not an oxymoron. As a vision or a mission, public health refers to the collective pursuit of a shared human good.75 Analytically, public health can be viewed as a reframing of health problems. Public health means not only the health of the public but also health in the public and by the public. Health problems are socially rooted, and solutions addressing these roots should be social solutions. To effectively promote public health, a discursive environment needs to be built by framing where health can be thought of and talked about in terms of communal consequences and responsibilities. Intervention strategies aimed at encouraging interpersonal advocacies and communicative behaviors need to be designed.

Acknowledgments

I thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and guidance.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed for this article because it did not involve human particpants.

Endnotes

- 1. Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick: Britain, 1800-1854 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 1.

- 2. Drew Leder, The Absent Body (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990)

- 3. Joel Best, Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems (New York, NY: Aldine De Gruyter, 1995)

- 4. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1991), http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED332957 (accessed December 7, 2007)

- 5. Jeremy Howell and Alan Ingham, “From Social Problem to Personal Issue: The Language of Lifestyle,” Cultural Studies 15, no. 2 (2001): 326–351.

- 6. Ibid, 330.

- 7. Ibid, 335.

- 8. Sylvia Noble Tesh, Hidden Arguments: Political Ideology and Disease Prevention Policy (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988)

- 9. Richard G. Wilkinson, Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality (London, UK: Routledge, 1997)

- 10. Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick.

- 11. Bruce G. Link and Jo Phelan, “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35, extra issue (1995): 80. [PubMed]

- 12. J. O. Hill, “Environmental Contributions to the Obesity Epidemic,” Science 280, no. 5368 (1998): 1371–1374. ; Regina G. Lawrence, “Framing Obesity: The Evolution of News Discourse on a Public Health Issue,” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 9, no. 3(2004): 56–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Kelly D. Brownell, “Then Environment and Obesity,” eds. Christopher G. Fairburn and Kelly D. Brownell, Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Comprehensive Handbook, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2002), 433–438.

- 14. M Malmström, J Sundquist, and S E Johansson, “Neighborhood Environment and Self-Reported Health Status: A Multilevel Analysis,” American Journal of Public Health 89, no. 8 (1999): 1181–1186; Steven Cummins et al., “Neighbourhood Environment and Its Association with Self Rated Health: Evidence from Scotland and England,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59, no. 3(2005): 207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky, Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1983), 16.

- 16. Nurit Guttman and Charles T. Salmon, “Guilt, Fear, Stigma and Knowledge Gaps: Ethical Issues in Public Health Communication Interventions,” Bioethics 18, no. 6 (2004): 531–552. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. Nurit Guttman and William Harris Ressl, “On Being Responsible: Ethical Issues in Appeals to Personal Responsibility in Health Campaigns,” Journal of Health Communication 6, no. 2, (2001): 117–136. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Robert Crawford, “You Are Dangerous to Your Health: The Ideology and Politics of Victim Blaming,” International Journal of Health Services 7, no. 4 (1977): 663–680. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Caroline C. Wang, “Portraying Stigmatized Conditions: Disabling Images in Public Health,” Journal of Health Communication 3, no. 2 (1998): 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Deborah Lupton, “Toward the Development of Critical Health Communication Praxis,” Health Communication 6, no. 1 (1994): 55–67.

- 21. Lawrence Wallack, “Media Advocacy: A Strategy for Empowering People and Communities,” Journal of Public Health Policy 15, no. 4 (1994): 420. [PubMed]

- 22. Charles T. Salmon, Information Campaigns: Balancing Social Values and Social Change (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1989)

- 23. Howell and Ingham, “From Social Problem to Personal Issue,” 344.

- 24. Ibid.

- 25. Claudine Herzlich, Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Analysis (London, UK: Academic Press, 1973)

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. Andrew C. Harper, The Health of Populations: An Introduction (New York, NY: Springer, 1986)

- 29. World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en (accessed October 2, 2013)

- 30. Julie Green, “Accidents and the Risk Society,” ed. Robin Bunton et al., The Sociology of Health Promotion: Critical Analyses of Consumption, Lifestyle and Risk (London, UK: Routledge, 1995), 117.

- 31. Niklas Luhmann, Risk: A Sociological Theory (New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 1993), 16.

- 32. John Schulenberg, Jennifer Maggs, and Klaus Hurrelmann, “Negotiating Developmental Transitions During Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Health Risks and Opportunities,” ed. John Schulenberg et al., Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 1–22.

- 33. Ruth Beyth-Marom and Baruch Fischhoff, “Adolescents’ Decisions About Risks: A Cognitive Perspective,” ed. John Schulenberg et al., Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 110–138.

- 34. Mohan J. Dutta-Bergman, “Theory and Practice in Health Communication Campaigns: A Critical Interrogation,” Health Communication 18, no. 2 (2005): 103–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35. Nancy K. Janz and Marshall H. Becker, “The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later,” Health Education Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1984): 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36. Icek Ajzen and Martin Fishbein, Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980)

- 37. Kim Witte, “Putting the Fear Back into Fear Appeals: The Extended Parallel Process Model,” Communication Monographs 59, no. 4 (1992): 329–349.

- 38. Dolores Albarracín and Robert S. Wyer, “The Cognitive Impact of Past Behavior: Influences on Beliefs, Attitudes, and Future Behavioral Decisions.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79, no. 1 (2000): 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39. Wallack, “Media Advocacy: A Strategy for Empowering People and Communities,” 420. [PubMed]

- 40. Jonathan Lomas, “Social Capital and Health: Implications for Public Health and Epidemiology,” Social Science & Medicine 47, no. 9 (1998): 1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41. Alan Petersen and Deborah Lupton, The New Public Health: Health and Self in the Age of Risk (London, UK: Sage, 2000), 89.

- 42. Peggy Glider “Challenging the Collegiate Rite of Passage: A Campus-Wide Social Marketing Media Campaign to Reduce Binge Drinking,” Journal of Drug Education 31, no. 2 (2001): 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43. H. Wesley Perkins, “Social Norms and the Prevention of Alcohol Misuse in Collegiate Contexts,” Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, suppl. no. 14 (2002): 164; Kim L. Johnston and Katherine M. White, “Binge-Drinking: A Test of the Role of Group Norms in the Theory of Planned Behaviour,” Psychology & Health 18, no. 1 (2003): 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. Roslyn Lindheim and S. Leonard Syme, “Environments, People, and Health,” Annual Review of Public Health 4 (1983): 335–359. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45. Zhongdang Pan and Jack M. McLeod, “Multilevel Analysis in Mass Communication Research,” Communication Research 18, no. 2 (1991): 140–173.

- 46. Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler, Connected: the Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives: How Your Friends’ Friends’ Friends Affect Everything You Feel, Think, and Do (New York, NY: Back Bay Books, 2011)

- 47. Ibid.

- 48. Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler, “The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network Over 32 Years,” New England Journal of Medicine 357, no. 4 (2007): 370–379. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49. Ibid.

- 50. Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler, “The Collective Dynamics of Smoking in a Large Social Network,” New England Journal of Medicine 358, no. 1 (2008): 2249–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Neel Rao, Markus Mobius, and Tanya Ronsenblat, “Social Networks and Vaccination Decisions” (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Working Paper No. 07-12, November 6, 2007), http://ssrn.com/abstract=1073143 (accessed October 7, 2009)

- 52. Petersen and Lupton, The New Public Health: Health and Self in the Age of Risk.

- 53. Lawrence Wallack and Regina Lawrence, “Talking About Public Health: Developing America’s ‘Second Language’,” American Journal of Public Health 95, no. 4 (2005): 567–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54. Ibid.

- 55. Ibid.

- 56. Robert M. Entman, “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm,” Journal of Communication 43, no. 4 (1993): 51–58.

- 57. Zhongdang Pan and Gerald Kosicki, “Framing Analysis: An Approach to News Discourse,” Political Communication 10, no. 1 (1993): 55–75.

- 58. Shanto Iyengar, Is Anyone Responsible?How Television Frames Political Issues (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991)

- 59. William A. Gamson, Talking Politics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992)

- 60. David A. Snow and Robert D. Benford, “Master Frames and Cycles of Protest,” ed. Aldon D. Morris and Carol McClurg Mueller, Frontiers in Social Movement Theory (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 133–155.

- 61. Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” Econometrica 47, no. 2 (1979): 263.

- 63. Alexander J. Rothman and Peter Salovey, “Shaping Perceptions to Motivate Healthy Behavior: The Role of Message Framing.,” Psychological Bulletin 121, no. 1 (1997): 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64. David A. Snow and Robert D. Benford, “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization,” ed. Bert Klandermans et al., From Structure to Action: Comparing Social Movement Research Across Cultures (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1988)

- 65. Katherine W. Hawkins and Darren L. Linvill, “Public Health Framing of News Regarding Childhood Obesity in the United States,” Health Communication 25, no. 8 (2010): 709–717; Jina H. Yoo and Junghyun Kim, “Obesity in the New Media: A Content Analysis of Obesity Videos on YouTube,” Health Communication 27, no. 1 (2012): 86–97; Sei-Hill Kim and L. Anne Willis, “Talking About Obesity: News Framing of Who Is Responsible for Causing and Fixing the Problem,” Journal of Health Communication 12, no. 4 (2007): 359–376.

- 66.Kim and Willis, “Talking About Obesity.”

- 67.Lawrence, “Framing Obesity.”

- 68. Sarah Nettleton and Robin Bunton, “Sociological Critiques of Health Promotion,” ed. Robin Bunton et al., The Sociology of Health Promotion: Critical Analyses of Consumption, Lifestyle, and Risk (London, UK: Routledge, 1995), 44.

- 69. Stephen J. Kunitz, The Health of Populations: General Theories and Particular Realities (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007)

- 70. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Obesity and Overweight for Professionals: Resources: Multimedia - DNPAO – CDC,” http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/resources/multimedia.html (accessed August 17, 2013)

- 71. Robert N. Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007)

- 72.Wallack and Lawrence, “Talking About Public Health.”

- 73. Marc Steinberg, “Tilting the Frame: Considerations on Collective Action Framing from a Discursive Turn,” Theory and Society 27, no. 6 (1998): 845–872.

- 74. Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75. Scott C. Ratzan, “Health Literacy: Communication for the Public Good,” Health Promotion International 16, no. 2 (2001): 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed]