Abstract

Listeriosis is a disease primarily of ruminants caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Ruminants either demonstrate manifestations of the encephalitic, septicemic, or reproductive form of listeriosis. The pathological and molecular findings with encephalitic listeriosis in a 5.5-month-old, male, mixed-breed goat and a 3-year-old Texel-crossed sheep from northern Paraná, Brazil are described. Clinically, the kid demonstrated circling, lateral protrusion of the tongue, head tilt, and convulsions; the ewe presented ataxia, motor incoordination, and lateral decumbency. Brainstem dysfunctions were diagnosed clinically and listeriosis was suspected. Necropsy performed on both animals did not reveal remarkable gross lesions; significant histopathological alterations were restricted to the brainstem (medulla oblongata; rhombencephalitis) and were characterized as meningoencephalitis that consisted of extensive mononuclear perivascular cuffings, neutrophilic and macrophagic microabscesses, and neuroparenchymal necrosis. PCR assay and direct sequencing, using genomic bacterial DNA derived from the brainstem of both animals, amplified the desired 174 base pairs length amplicon of the listeriolysin O gene of L. monocytogenes. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that the strains associated with rhombencephalitis during this study clustered with known strains of L. monocytogenes lineage I from diverse geographical locations and from cattle of the state of Paraná with encephalitic listeriosis. Consequently, these strains should be classified as L. monocytogenes lineage I. These results confirm the active participation of lineage I strains of L. monocytogenes in the etiopathogenesis of the brainstem dysfunctions observed during this study, probably represent the first characterization of small ruminant listeriosis by molecular techniques in Latin America, and suggest that ruminants within the state of Paraná were infected by the strains of the same lineage of L. monocytogenes.

Keywords: brainstem dysfunctions, rhombencephalitis, neuropathology, listeriolysin gene, epidemiology, Listeria monocytogenes

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium that produces three distinct, rarely overlapping, syndromes predominantly in ruminants, and other domestic animals (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie et al., 2007; George 2009; Zachary 2012). Listeriosis also occurs in humans and is frequently associated with the ingestion of contaminated milk and/or milk-derived products (Timoney et al., 1992). In Brazil, cases of human listeriosis might be underdiagnosed, while the incidence of contaminated animal products is variable, being 0–38% for milk and 0–25% in cheese-based products (Barancelli et al., 2011); this variation reflects the type of product analysed and the geographical location of the study area.

Three recognized syndromes of listeriosis are described in domestic animals: a) septicemic disease of young animals, with involvement of the liver, spleen, and other organs; 2) reproductive disease, associated with metritis, placentitis, and abortion occurring predominantly in sheep and cattle; and c) meningoencephalitis, more frequently diagnosed in adult sheep, goats, and cattle (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007; Zachary 2012). Although this bacterium occurs worldwide, disease in domestic animals is more frequently diagnosed in temperate countries (George 2009). In Brazil, there are few descriptions of listeriosis in domestic animals, with disease occurring in cattle (Schwab et al., 2004; Galiza et al., 2010), sheep (Schwab et al., 2004; Ribeiro et al., 2006; Rissi et al., 2010), and goats (Schwab et al., 2004; Rissi et al., 2006). Data collected from diagnostic laboratories in Brazil have suggested that the occurrence of ruminant encephalitic listeriosis (REL) is significantly reduced (Sanches et al., 2000; Guedes et al., 2007; Galiza et al., 2010). In northern Brazil, incidence levels vary between species: being 0.9% (1/111) for cattle (Galiza et al., 2010), 8.2% (3/34) in goats, and 3.45% (1/29) in sheep (Guedes et al., 2007). Studies done in southern Brazil have also reported reduced incidence rates: being 3% (3/100) in goats (Rissi et al., 2006) and 0.98% (3/305) in cattle (Sanches et al., 2000). However, there is no description of small ruminant listeriosis in the state of Paraná.

The histopathological diagnosis of REL is based on the observation of microabscesses and/or extensive perivascular mononuclear cuffings associated with intralesional Gram positive bacterium particularly at the brainstem (Maxie and Youssef 2007; Zachary 2012). Confirmation of REL has been based on the combination of these characteristic histopathological findings associated with immuno-histochemistry (Wilkins et al., 2000; Schwab et al., 2004; Ribeiro et al., 2006; Rissi et al., 2006), bacterial isolation (Yousif et al., 1984; McLaughlin et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1995), serology (Börkü et al., 2006), and molecular biology (Wiedmann et al., 1997; Evans et al., 2004; Langohr et al., 2006; Bundrant et al., 2011).

Although molecular investigations have been used worldwide to characterize REL (Wiedmann et al., 1997; Evans et al., 2004; Langohr et al., 2006; Bundrant et al., 2011), reports of the utilization of this diagnostic technique to identify listeriosis in domestic animals from Brazil or South America is scarce. However, REL was successfully characterized in cattle from the state of Paraná by a combination of histopathological and molecular techniques (Headley et al., 2013), and there is one unsuccessful attempt of molecular identification in goats (Rissi et al., 2006). Molecular diagnostic strategies used to identify L. monocytogenes in domestic animals include: the PCR amplification of 174 base pairs (bp) of the listeriolysin (hly) O gene that is specie-specific (Deneer et al., 1991; Wesley et al., 2002); randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (Wesley et al., 2002); PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay (Evans et al., 2004); PCR-serotyping of the 16S rRNA gene (Langohr et al., 2006); and multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) (Bundrant et al., 2011). Additionally, strains of L. monocytogenes can be subtyped into four distinct evolutionary lineages: lineage I, II, and III (Rasmussen et al., 1995; Wiedmann et al., 1997; Roberts et al., 2006), and IV (Liu 2006; Roberts et al., 2006), based on the pathological potential to cause disease outbreaks in humans and domestic animals (Wiedmann et al., 1997; Liu 2006).

This report presents the clinicopathological and molecular findings associated with caprine and ovine encephalitic listeriosis in northern Paraná, Brazil.

Materials and Methods

Clinical history: caprine

A 5.5-month-old, male, crossbreed goat was admitted at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH), Universidade Norte de Paraná, Arapongas, Paraná, southern Brazil in early September, 2011, with a history of circling and protrusion of the tongue towards the right side of the mouth. On arrival at the VTH, the goat demonstrated head tilt, pedalling movement, convulsions in addition to the manifestations observed at the farm. A neurological diagnosis of brainstem dysfunction was established and listeriosis was suspected. The neurological manifestations became intense and progressive, the owner solicited euthanasia, and a routine necropsy was realized.

This animal originated from a herd of 200 goats, located approximately 40 km from Londrina; these animals are raised primarily for commercial meat production and milk for household usage. An on-farm investigation revealed that the goats were housed in three individual pens divided into several subunits; the floor of one pen was elevated and consisted of ripped wooden strips, while others were made up of compacted organic material. There was no reported utilization of silage at the farm prior to or at the time of this investigation. The animals received water ad libitum and were fed daily freshly cut Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum), commercially produced mineral salt and corn, and leftover stalks of sugarcane destroyed by the recent inclement weather; some standing sugarcane stalks demonstrated signs of decomposition. The owner indicated that three days previously a female goat had similar neurological manifestations and died; he further commented that a year ago another goat demonstrated muscular tremors, circling with sudden death, and that there have been episodes of late-phase abortions that coincided with severe intestinal parasitism. Blood samples were randomly collected from 16 goats, without apparent manifestation of disease, by venepuncture in EDTA tubes and stored at −20 °C.

Clinical history: ovine

A 3-year-old, female, Texel-cross sheep was taken to the VTH in mid-December 2011 due to clinical manifestations of muscular tremors, motor incoordination, ataxia, and lateral decumbency. The referring veterinarian indicated that the neurological manifestations initiated 45 days prior to arrival at the University. These manifestations were observed on arrival at the Teaching Hospital, listeriosis was suspected, and the referring veterinarian requested euthanasia due to the prolonged nature of the neurological syndrome. This sheep originated from a farm located in Arapongas, Paraná, that contained 95 ewes used for reproduction. These animals are raised semi-extensively; they are housed in pens having floors derived from compacted wood shavings, are maintained on pastures of Panicum maximum cultivar Aruana and supplemented with commercially produced mineral salt and grounded corn; water derived from an artesian well is given ad libitum. The veterinarian further indicated that there were two recent unexplained episodes of abortion within the herd and this ewe was acquired from another farm 6 months before the onset of neurological dysfunctions.

Necropsy and sample collection

Routine necropsies were performed soon after euthanasia. Tissues fragments (brain, liver, intestines, liver, lungs, and kidneys) of both animals were fixed by emersion in 10% buffered formalin solution and routinely processed for histopathological evaluation; brainstem fragments were also colored by the Gram stain. Duplicate sections of the brainstem, liver, and lungs were aseptically collected and maintained frozen until used for molecular analysis.

DNA extraction, PCR assay, and sequencing

Genomic bacterial DNA was extracted from the brainstem of the sheep and goat, and, from blood samples of asymptomatic sheep, by a combination of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and silica/guanidine isothiocyanate methods (Alfieri et al., 2006), and then maintained at −20 until usage. The PCR protocol used was based on previous studies (Wesley et al., 2002), with modifications. Briefly, the Lis1 and Lis2 primer pairs that selectively amplify 174 bp of the hly gene of L. monocytogenes were used (Deneer and Boychuk 1991; Wesley et al., 2002). Amplification was done to a final volume of 50 μL, containing 50 pmole of each primer, 200 μM of dNTP, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 10 μL 10X Buffer (Invitrogen Corp; Carlsbad, CA, USA), 6.5 mM MgCl2, 5 μL of extracted DNA, and 22.5 μL of nuclease-free water (Invitrogen Corp; Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PCR amplification cycle consisted of an initial denaturation (94 °C for 4 min), followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 1 min), primer annealing (60 °C for 1 min) and extension (72 °C for 1 min), with a final extension (72 °C for 5 min). Positive control consisted of genomic DNA obtained from an unpublished case of L. monocytogenes derived from milk samples; negative control consisted of nuclease-free water (Invitrogen Corp; Carlsbad, CA, USA).

The obtained PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and examined under UV light. The products were then purified (illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and submitted for direct sequencing with the sense and anti-sense primers. The partial sequences were initially compared by the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Phylogenetic trees and sequence alignments were then created by using MEGA 5.2.1 (Tamura et al., 2011), constructed by the neighbour-joining method, based on 1,000 bootstrapped data sets. Distances values were calculated by using the Kimura 2 parameter model.

Results

Necropsy and histopathological findings

Gross findings of the goat consisted predominantly of congested meningeal vessels, pulmonary edema, hemorrhage, and congestion with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes due to five examples of the cestode, Moniezia spp., within the small intestine; a sagittal section through the brain revealed discrete congestion of the brainstem. Significant gross lesions were not observed in other organs/systems. Remarkable gross lesions of the sheep were restricted to congestion of meningeal vessels.

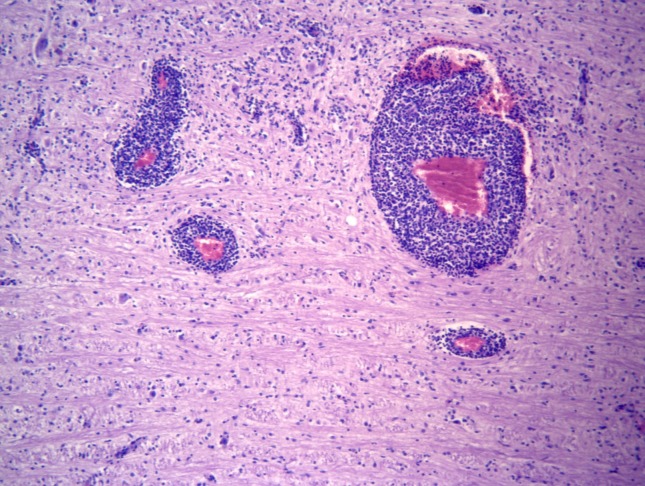

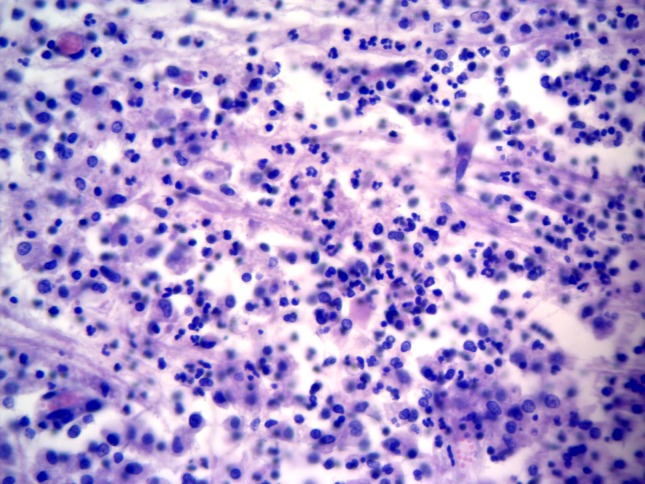

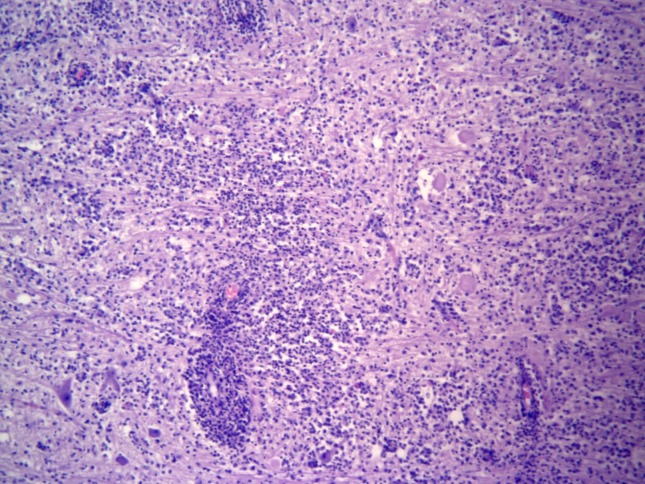

Significant histological alterations of both animals were similar in nature and restricted predominantly to the brainstem (medulla oblongata; rhombencephalitis), but there was also discrete involvement of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of the goat; all other organs/systems of both animals were not affected. Brainstem lesions revealed meningoencephalitis and microabscesses (Figure 1). Meningoencephalitis was characterized by the accumulations of lymphocytes and plasma cells at the meninges, resulting in meningitis with vasculitis and perivasculitis, and with extensive mononuclear cuffs within the neuroparenchyma. These perivascular cuffs were of different sizes and shapes, and most were formed by more than four layers of mononuclear cells, consisting primarily of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and some macrophages (Figure 2). Within these areas of mononuclear cuffings there were foci of microabscesses, formed by predominant neutrophilic accumulations admixed with few macrophages (Figure 3); alternatively, they were microabscesses that were predominantly macrophagic. In some areas, the coexistent vascular cuffings and inflammatory exudate resulted in destruction of the neuroparenchyma (Figure 4); this being more severe in the goat relative to the sheep. Large quantities of Gram-positive bacteria were observed predominantly within neurones, but also within macrophages, neutrophils, endothelial cells of several destroyed vessels, and loose within the neuroparenchyma. Bacteria were more predominant in areas of neuroparenchymal necrosis. Additionally, there was astrocytosis, vascular congestion, neuronal necrosis, and neuronophagia within the areas containing the inflammatory reaction and microabscesses. Further, manifestations of histological disease of the goat were characterized by discrete vasculitis and perivascular edema of the cerebellum and meningitis with vasculitis and foci of small perivascular cuffings (formed by less than 2 layers of inflammatory cells) of the cerebral cortex.

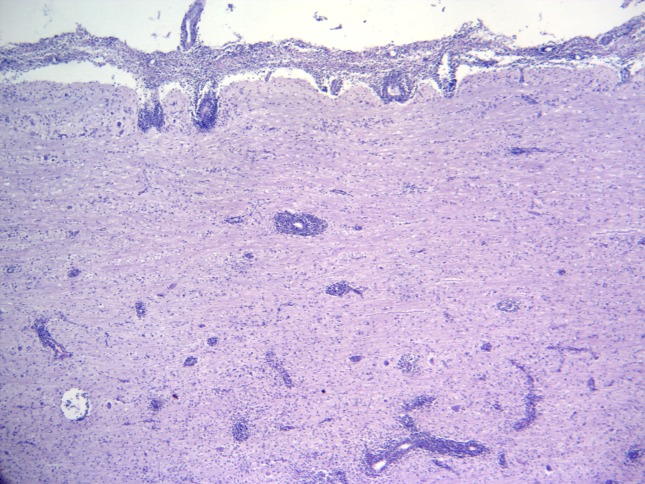

Figure 1.

Listeria monocytogenes-induced rhombencephalitis; medulla oblongata; mixed-breed goat. There is marked inflammation of the meninges and neuroparenchyma resulting in subacute meningoencephalitis (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain; 4× Obj.).

Figure 2.

Medulla oblongata; mixed-breed goat. The mononuclear perivascular cuffings are formed by more than four layers of lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory cells. (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain; 10× Obj.).

Figure 3.

Listeria rhombencephalitis; medulla oblongata; mixed-breed sheep. The microabscesses is formed by mixed inflammatory exudate (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain; 20× Obj.).

Figure 4.

Encephalitic listeriosis; medulla oblongata; mixed-breed goat. There is destruction of the neuroparenchyma due to the accumulation of microabscesses, perivascular cuffings, and the influx of inflammatory cells. (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain; 40× Obj.).

PCR assay, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis of fragments of the listeriolysin O gene

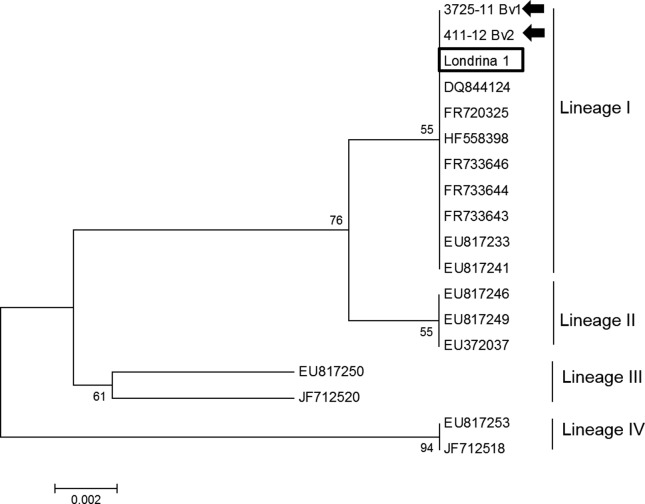

The Lis1 and Lis2 primer pairs amplified the desired product size of 174 bp that was derived from DNA extracted only from the brainstem of the both animals. The partial sequences obtained during this study have been named L. monocytogenes Londrina strain 1 and 2. Initial BLAST analysis revealed that the sequences of the Londrina strains have 100% similarity with other sequences of the hly gene deposited in GenBank. Phylogenetic analysis based on the hly gene of L. monocytogenes revealed that the strains from this study clustered with known stains of L. monocytogenes lineage I, including strains recently identified in cattle from the state of Paraná with encephalitic listeriosis (Headley et al., 2013). All blood-derived genomic DNA samples revealed negative results by PCR assay. The sequences used for phylogenetic analyses during this study are given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationship of selected strains of Listeria monocytogenes, representing the four distinct lineages, based on the listeriolysin gene. The GenBank accession numbers of the isolates used are given. The strain derived from this study is highlighted (within box); those from a recent investigation of bovine encephalitic listeriosis are shown (arrows).

Discussion

The neurological manifestations associated with the histopathological findings observed within the brainstem (medulla oblongata) of these animals are consistent with those previously described in REL (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007; Zachary 2012). Additionally, the molecular data obtained from genomic bacterial DNA extracted from the same anatomic location of both animals revealed the desired 174 bp amplicon of the hly gene of L. monocytogenes, by specie-specific primers (Deneer and Boychuk 1991; Wesley et al., 2002). Therefore, these findings confirm the active participation of L. monocytogenes in the etiopathogenesis of the brainstem lesions with the consequent neurological manifestations presented by these small ruminants and contribute to the geographical distribution of ruminant listeriosis in Brazil. As far as the authors’ are aware, this report might represent the first successful characterization of L. monocytogenes in small ruminants by the use of molecular techniques aided by histopathology in Brazil and South America, and also possibly in Latin America.

The histopathological alterations observed within the brainstem of these animals are pathognomonic for REL (Maxie and Youssef 2007). Nevertheless, a recent study has classified ruminant encephalitic listeriosis in three distinct progressive histopathological patterns based on the cellular composition of microabscesses (Oevermann et al., 2010). Accordingly, there is type 1 microabscesses (acute encephalitic listeriosis), formed predominantly by neutrophilic exudate with few macrophages; type 2 (chronic listeriosis), with the predominance of macrophages and reduced neutrophilic exudate; and type 3 microabscesses (subacute encephalitic listeriosis), formed by a combination of abscesses that are predominantly neutrophilic and macrophagic (Oevermann et al., 2010). Consequently, the histopathological lesions observed in the brainstem of both animals are consistent with subacute listerial encephalitis; this neurological pattern might represent the most frequent manifestation of REL (Oevermann et al., 2010).

Although the histopathological manifestations of listerial encephalitis is considered restricted to the brainstem (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007; Zachary 2012), characteristic lesions were observed in the cerebellum of two cases described in southern Brazil (Rissi et al., 2006). In addition, 85.91% (189/220) of ruminants with encephalitic listeriosis, from a European study, had lesions that extended from the brainstem rostrally to the upper spinal cord with cerebellar and cerebral involvement (Oevermann et al., 2010). Extra brainstem lesions were discrete within the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of the goat. Therefore, these results suggest that for an effective histopathological characterization of listeriosis in ruminants, the brainstem and other regions of the CNS should be evaluated. Nevertheless, the brainstem continues to be the most likely neuroanatomical location to observe characteristic listerial meningoencephalitis in ruminants (Maxie and Youssef 2007; Oevermann et al., 2010; Zachary 2012).

Although there are several molecular diagnostic techniques (Wesley et al., 2002; Evans et al., 2004; Langohr et al., 2006; Bundrant et al., 2011) to characterize L. monocytogenes, we opted for the amplification of the hly gene with subsequent phylogenetic analysis. This is partially because ruminant listeriosis in Brazil is not of significant economic importance to the national herd considering the reduced levels of occurrence described in cattle, sheep, and goats (Sanches et al., 2000; Guedes et al., 2007; Galiza et al., 2010), and the marked absence of silage and hay feeding of ruminants relative to temperate zones, which makes ruminants in Brazil less susceptible to infection by L. monocytogenes (Headley et al., 2013). Hence, the objective of the current study was to confirm the participation of L. monocytogenes by molecular technique, since there are no reports of small ruminant listeriosis within the state in which these animals were housed, and few descriptions of small ruminant listeriosis in Brazil (Schwab et al., 2004; Ribeiro et al., 2006; Rissi et al., 2006; Guedes et al., 2007; Rissi et al., 2010). Additionally, the hly gene is highly conserved in L. monocytogenes, the primer pairs (Lis1; Lis2) are specie-specific, and differentiates L. monocytogenes from other species of Listeria (Deneer and Boychuk 1991); this further confirms that L. monocytogenes was involved in the brainstem lesions of these animals. The PCR results obtained with the specific-primer pairs used in this study are similar to previous reports (Deneer and Boychuk 1991; Wesley et al., 2002).

The phylogenetic data obtained when these strains were aligned with those deposited in GenBank demonstrated that the strains from this study clustered with other known strains of L. monocytogenes lineage I, including those from a recent study of bovine encephalitic listeriosis from the state of Paraná (Headley et al., 2013). Consequently, the strains from this investigation should be classified as L. monocytogenes lineage I. This finding is of significant importance to understand the epidemiology of L. monocytogenes, since listeriosis in animals is more frequently associated with lineage III strains (Liu 2006). Although lineage I strains of L. monocytogenes have been associated with outbreaks in domestic animals (Rasmussen et al., 1995), as occurred in a cattle from the state of Paraná (Headley et al., 2013), these strains are more frequently isolated in food-borne epidemics of listeriosis and in sporadic cases of human and animal listeriosis (Liu 2006; Roberts et al., 2006). Consequently, the strains of L. monocytogenes identified during this study from northern Paraná and those characterized in cattle from other geographical regions of Paraná (Headley et al., 2013) represent sporadic occurrences of REL due to lineage I strains; this is primarily because lineage I strains of L. monocytogenes are considered more pathogenic for humans than domestic animals (Jeffers et al., 2001; den Bakker et al., 2008). Collectively, these findings suggest that ruminants within the state of Paraná were infected by the strains of the same lineage of L. monocytogenes.

During this study, positive molecular findings were restricted only to fragments derived from the brainstem of both animals while blood samples from sheep without manifestation of disease, did not reveal the presence of L. monocytogenes. This might suggest that these small ruminants demonstrated only the encephalitic manifestations of listeriosis, since in most cases of listeriosis in domestic animals there is no overlapping of disease syndromes (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007). The negative PCR results obtained from the asymptomatic goats might indicate that only this goat within the herd had active manifestation of disease while the other animals evaluated were not bacteriemic and/or potential carriers of this bacterium. These negative PCR results might be related to the fact that ruminants are known to maintain this bacterium without manifestation of disease (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007), hence bacteremia was absent, and if present, the pathogen would have been more easily identified by PCR assay. Although the exact nature of carrier state in ruminant listeriosis has not been completely elucidated, this manifestation of disease might be associated with the identification of L. monocytogenes from a large percentage of normal animals or due to elevated environmental contamination within a particular location (George 2009). Nevertheless, the clinical data obtained from the farmer (i.e., previous manifestations of circling disease terminating with death and episodes of late-phase abortion) and the consulting veterinarian (episodes of unexplained abortion) suggests that listeriosis might be endemic within these herds but not previously diagnosed. This sporadic occurrence of manifestations of listerial syndromes, as probably occurred within these farms, is a frequent epidemiological feature of listeriosis in ruminants (Maxie and Youssef 2007; George 2009).

The actual source of infection in these cases remains obscure; silage that is frequently associated with listerial meningoencephalitis of ruminants (Timoney et al., 1992; Maxie and Youssef 2007; George 2009) was not reportedly administered to the animals of these farms neither was silage/hay observed during an on farm-visit to the goat holding. However, the floor of the pen where the goat was maintained consisted of accumulated organic material and that of the sheep of compacted wood shavings, and must be considered as possible sources of contamination (Maxie and Youssef 2007; George 2009). Additional the feeding of sugarcane stalks in stages of decomposition to the flock of goats cannot be excluded as a possible contaminant, resulting in abrasive lesions to the oral cavity that might have served as portals of entry to the trigeminal and cranial nerves that terminate within the brainstem (Zachary 2012). Decaying vegetation has been incriminated as source of infection in cases where ruminants have not been administered silage (George 2009), due to the aerobic environment and elevated pH of decaying material which favors the proliferation of L. monocytogenes (Timoney et al., 1992; George 2009).

These cases occurred during later winter in animals that were raised in a semi-intensive settings but without contact with silage or hay; most cases of listeriosis in the Northern hemisphere have been described during late winter and early spring (Summers et al., 1995; Maxie and Youssef 2007; George 2009), in association with the administration of silage and/or hay (Summers et al., 1995). Nevertheless, the isolated ingestion of contaminated silage is not sufficient to induced listeriosis in ruminants unless there is a concomitant lesion within the oral cavity (Zachary 2012). However, cases of listeriosis in ruminants from southern Brazil have occurred during the summer and spring in field animals (Rissi et al., 2006), while outbreaks of listeriosis in sheep was predominant during the summer, with other cases occurring in other seasons (Rissi et al., 2010). These data might suggest that a definite seasonal pattern of listeriosis in ruminants is not present within the Southern hemisphere; nevertheless, more cases would have to be diagnosed to understand the seasonal effects on the occurrence of listeriosis in domestic animals raised in Brazil. Additionally, other factors that might predispose ruminants to listeriosis include alkaline soil, fibrotic pastures, abrupt managerial changes, pregnancy, and intense rain or prolonged droughts (Timoney et al., 1992; Rissi et al., 2006).

In conclusion, L. monocytogenes DNA was identified from the brainstem of a sheep and goat with manifestations of neurological disease associated with bacterial rhombencephalitis. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that the strains identified during this study clustered with other known strains of L. monocytogenes lineage I from diverse geographical locations and from cattle originated from the state of Paraná. Consequently, these findings suggest that ruminants within the state of Paraná were infected by the same lineage of L. monocytogenes.

Acknowledgments

Drs Selwyn A. Headley, Alice F. Alfieri, and Amauri A. Alfieri are recipients of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Brazil) fellowships. The authors thank Drs Rodrigo Kenji Murate and Antônio Sversuti for submitting the animals for routine necropsy.

References

- Alfieri AA, Parazzi ME, Takiuchi E, Medici KC, Alfieri AF. Frequency of group A rotavirus in diarrhoeic calves in Brazilian cattle herds, 1998–2002. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2006;38:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s11250-006-4349-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barancelli GV, Silva-Cruz JV, Porto E, Oliveira CAF. Listeria monocytogenes: occurrence in dairy products and its implications in public health. Arq Inst Biol. 2011;78:155. [Google Scholar]

- Börkü MK, KU, Gazyaúci S, Zkanlar Y, Babür C, Kiliç S. Serological detection of listeriosis at a farm. Turk J Vet Anim Sci. 2006;30:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bundrant BN, Hutchins T, den Bakker HC, Fortes E, Wiedmann M. Listeriosis outbreak in dairy cattle caused by an unusual Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strain. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:155–158. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Didelot X, Fortes ED, Nightingale KK, Wiedmann M. Lineage specific recombination rates and microevolution in Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:277. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneer HG, Boychuk I. Species-specific detection of Listeria monocytogenes by DNA amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:606–609. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.606-609.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Smith M, McDonough P, Wiedmann M. Eye infections due to Listeria monocytogenes in three cows and one horse. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004;16:464–469. doi: 10.1177/104063870401600519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiza GJN, Silva MLCR, Dantas AFM, Simões SVD, Riet-Correa F. Diseases of the nervous system of cattle in the semiarid Northeastern Brazil. Pesq Vet Bras. 2010;30:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- George LW. Listeriosis. In: Smith BP, editor. Large Animal Internal Medicine. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1045–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes KMR, Riet-Correa F, Dantas AFM, Simões SVD, Miranda Neto EG, Nobre VMT, Medeiros RMT. Diseases of the central nervous system in goats and sheep of the semiarid. Pesq Vet Bras. 2007;27:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Headley SA, Fritzen JTT, Queiroz GR, Oliveira RAM, Alfieri AF, Santis GWD, Lisbôa JAN, Alfieri AA. Molecular characterization of encephalitic bovine listeriosis from southern Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers GT, Bruce JL, McDonough PL, Scarlett J, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. Comparative genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from human and animal listeriosis cases. Microbiology. 2001;147:1095–1104. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GC, Fales WH, Maddox CW, Ramos-Vara JA. Evaluation of laboratory tests for confirming the diagnosis of encephalitic listeriosis in ruminants. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1995;7:223–228. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langohr IM, Ramos-Vara JA, Wu CC, Froderman SF. Listeric meningoencephalomyelitis in a cougar (Felis concolor): characterization by histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular methods. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:381–383. doi: 10.1354/vp.43-3-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. Identification, subtyping and virulence determination of Listeria monocytogenes, an important foodborne pathogen. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:645–659. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, editor. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of domestic animals. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007. pp. 405–408. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin BG, Greer SC, Singh S. Listerial abortion in a llama. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1993;5:105–106. doi: 10.1177/104063879300500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oevermann A, Di Palma S, Doherr MG, Abril C, Zurbriggen A, Vandevelde M. Neuropathogenesis of naturally occurring encephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in ruminants. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:378–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen OF, Skouboe P, Dons L, Rossen L, Olsen JE. Listeria monocytogenes exists in at least three evolutionary lines: evidence from flagellin, invasive associated protein and listeriolysin O genes. Microbiology. 1995;141(Pt 9):2053–2061. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro LAO, Rodrigues NC, Fallavena LCB, Oliveira SJ, Brito MA. Listeriose em rebanho de ovinos leiteiros na região serrana do Rio Grande do Sul: relato de caso. Arq Bras Med Vet Zoot. 2006;58:316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Rissi DR, Kommers GD, Marcolongo-Pereira C, Schild AL, Barros CSL. Meningoencephalitis in sheep caused by Listeria monocytogenes. Pesq Vet Bras. 2010;30:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rissi DR, Rech RR, Barros RR, Kommers GD, Langohr IM, Pierezan F, Barros CSL. Listeric meningoencephalitis in goats. Pesq Vet Bras. 2006;26:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Nightingale K, Jeffers G, Fortes E, Kongo JM, Wiedmann M. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes lineage III. Microbiology. 2006;152:685–693. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanches AWD, Langohr IM, Stigger AL, Barros CSL. Diseases of the central nervous system in cattle of southern Brazil. Pesq Vet Bras. 2000;20:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab JP, Edelweiss MIA, Graça DL. Immunohistochemical identification of Listeria monocytogenes in the brain tissue of ruminants. Rev Port Ci Vet. 2004;99:65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Summers BA, Cummings JF, de Lahunta A. Veterinary Neuropathology: Baltimore; Mosby: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timoney JF, Gillespie JH, Scott FW, Barlough JE. Hagan and Burner’s microbiology and infectious diseases of domestic animals. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wesley IV, Larson DJ, Harmon KM, Luchansky JB, Schwartz AR. A case report of sporadic ovine listerial menigoencephalitis in Iowa with an overview of livestock and human cases. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2002;14:314–321. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann M, Bruce JL, Keating C, Johnson AE, McDonough PL, Batt CA. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2707–2716. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2707-2716.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins PA, Marsh PS, Acland H, Del Piero F. Listeria monocytogenes septicemia in a Thoroughbred foal. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:173–176. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif YA, Joshi BP, Ali HA. Ovine and caprine listeric encephalitis in Iraq. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1984;16:27–28. doi: 10.1007/BF02248925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachary JF. Listeriosis. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, editors. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier/Mosby; 2012. pp. 192–195. [Google Scholar]