Abstract

Propolis is a natural product widely used for humans. Due to its complex composition, a number of applications (antimicrobial, antiinflammatory, anesthetic, cytostatic and antioxidant) have been attributed to this substance. Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a eukaryotic model we investigated the mechanisms underlying the antioxidant effect of propolis from Guarapari against oxidative stress. Submitting a wild type (BY4741) and antioxidant deficient strains (ctt1Δ, sod1Δ, gsh1Δ, gtt1Δ and gtt2Δ) either to 15 mM menadione or to 2 mM hydrogen peroxide during 60 min, we observed that all strains, except the mutant sod1Δ, acquired tolerance when previously treated with 25 μg/mL of alcoholic propolis extract. Such a treatment reduced the levels of ROS generation and of lipid peroxidation, after oxidative stress. The increase in Cu/Zn-Sod activity by propolis suggests that the protection might be acting synergistically with Cu/Zn-Sod.

Keywords: propolis, antioxidant, oxidative stress, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Introduction

Aerobic organisms have to deal with the toxic effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These reactive species can be formed during stress conditions such as heat shock, dehydration, toxic chemicals, UV and ionizing radiation (Lushchak, 2011). Furthermore, aerobic life style is a potential source of ROS since oxygen can be partially reduced during respiration (Lushchak, 2011; Morano et al., 2011). Indeed, when the generation of ROS overwhelms the cellular antioxidant components a drastic oxidative stress is generated. Oxidative stress promotes several damages to cell structures such as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. Hence, modifications in such molecules have been strongly related to a number of diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and also to the process of aging (Hwang and Kim, 2007; Valko et al., 2007; Liedhegner et al., 2012).

Cellular defense mechanisms against ROS-induced oxidative stress involve enzymatic and/or non-enzymatic factors. Enzymatic defense encompasses enzymes such as superoxide dismutases, glutathione transferases, catalase and others involved in removal, repair or detoxification of damaged intracellular components (Scandalios, 2005). On the other hand, non-enzymatic antioxidants such as ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), α-tocopherol (Vitamin E), glutathione (GSH), carotenoids, flavonoids are mainly related to the process of ROS elimination and detoxification of pernicious components damaged by ROS (Scandalios, 2005; Valko et al., 2006).

In the last years, an increasing interest in producing or discovering new antioxidant molecules from “functional foods” is emerging. This term is used for foods that can provide not only basic nutritional or energetic requirements, but also additional components with physiological benefits, such as antioxidants which are involved in protection against ROS (Viuda-Martos et al., 2008). Aiming at reducing diseases and also the process of aging, food industries are developing antioxidant substances and/or enriched foods with antioxidants. In this field, compounds originated in the beehive, as honey, propolis and royal jelly have gained prominence (Gómez-Caravaca et al., 2006; Bouayed and Bohn, 2010; Sforcina and Bankovab, 2011).

Propolis is a natural and non-toxic resin produced by honey bees (Apis mellifera). It is extensively used in folk medicine presenting several biological applications such as immunomodulatory, antitumor, antiinflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antiparasite activities (Dobrowolski et al., 1991; Marcucci et al., 2001; Gómez-Caravaca et al., 2006; Souza et al., 2007; Bouayed and Bohn, 2010; Sforcina and Bankovab, 2011). Currently, this product has also been used by food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (Viuda-Martos et al., 2008). The complexity of its chemical composition is mainly due to the site where it is produced by bees. In fact, natural factors such as type of vegetation, zone of temperature and seasonality determine its composition (Gómez-Caravaca et al., 2006; Viuda-Martos et al., 2008; Sforcina and Bankovab, 2011). Although it is possible to find differences in propolis composition, most of the samples share common characteristics in their overall chemistry (Marcucci et al., 2001; Gómez-Caravaca et al., 2006; Sforcina and Bankovab, 2011). Propolis chemistry describes the existence of at least 300 different compounds; it contains 50% resin which is composed mainly by polyphenols (flavonoids, phenolic acids and their esters); 30% wax, 10% essential oils, 5% pollen and 5% other organic compounds (Marcucci et al., 2001). Due to its composition, propolis could act as a promissory antioxidant substance reacting and scavenging ROS, however, the exact protective mechanism displayed by propolis is unknown.

In order to establish new insights regarding the antioxidant properties of propolis, we investigated the protective role of propolis during exposure of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to oxidative stress generated by H2O2 and menadione. Due to biochemical and molecular similarities with human cells, the yeast S. cerevisiae has been shown to be a powerful eukaryotic model for understanding the cellular response against stress damages (Mager and Winderickx, 2005; Khurana and Lindquist, 2010). In this work, we also report the first evidence for propolis activation of the antioxidant enzyme Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase.

Material and Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Culture media components were purchased from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Preparation of propolis extract

Crude propolis from Guarapari was a kind gift by Prof. Monica Freimman de Souza Ramos (Faculty of Pharmacy, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Guarapari is located in the coastal zone of the Brazilian state of Espirito Santo, with a tropical Aw climate possessing reminiscences of the original Atlantic forest. Propolis extract was prepared by static maceration of 6.0 g of the grounded crude propolis with 30 mL of absolute ethanol for one week at 28 °C. After filtration to remove the insoluble residues, the extract was kept in a freezer until use as described by Souza et al., 2007 (Souza et al., 2007).

Yeast strains and growth conditions

Wild type strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 (MATa his3 leu2 met15 ura3) and its isogenic mutants ctt1, sod1, gsh1, gtt1 and gtt2 harboring, respectively, the genes CTT1, SOD1, GSH1, GTT1 and GTT2 interrupted by the gene KanMX4 (Euroscarf, Frankfurt, Germany) were used in this work. Stocks of yeast strains were maintained on solid 2% YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% peptone, and 2% agar). In the case of mutant strains the medium also contained 0.02% of geneticine. For all experiments, cells were grown in liquid 2% YPD medium using an orbital shaker at 28 °C and 160 rpm with the ratio of flask volume/medium of 5/1.

Oxidative stress conditions

Cells (50 mg) at the first exponential phase growing on 2% YPD were directly stressed (15 mM menadione or 2 mM H2O2 during 1 h at 28 °C/160 rpm), or previously treated with propolis (25 μg/mL) during 1 h at 28 °C/160 rpm (Castro, et al., 2007; Fernandes et al., 2007; Dani et al., 2008). Immediately after adaptive treatment, cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 rpm/ 5 min/4 °C), washed with distilled water to remove the excess of propolis in the medium and then resuspended in the original growth medium to oxidative stress.

Tolerance determination

Cell viability was analyzed by plating cells (400 μg), after appropriate dilution (1000 x), in triplicate on solidified 2% YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% peptone, and 2% agar) (Castro, et al., 2007; Dani et al., 2008). The plates were incubated at 28 °C/72 h and then colonies counted. Survival, expressed as percentage, was determined before and after oxidative stress condition, using cells treated or not with propolis (25 μg/mL).

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was assayed in cells exposed directly or propolis pre-treated to oxidative stress. Cells (50 mg) cooled on ice were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 rpm/ 5 min/ 4 °C), washed twice with distilled water and resuspended with 0.5 mL of 10% trichloracetic acid (TCA) in a test tube containing 1.5 g of glass beads. Cells were disrupted by 6 cycles of 20 s agitation on a vortex mixer followed by 20 s on ice. The extracts were used to detect malondialdehyde (MDA), a final product of lipid oxidation, according to Steels et al. (1994) (Steels et al., 1994).

Detection of superoxide dismutase activity

Total protein extract was prepared from exponential cells (50 mg) treated or not with 25 μg/mL propolis according to Mannarino et al. (2011) (Mannarino et al., 2011). Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Stickland (1951) (Stickland, 1951). Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase activity was analyzed loading 30 μg of proteins in native 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was carried out using a Mini-Protean from Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad laboratories Inc, USA) at 25 °C, 100 mV during 2 h. After electrophoresis, the gel was immersed in a solution containing 2.5 mM nitrobluetetrazolium (NBT) and 86 μM riboflavin. The reaction (10 min.) of visible light with riboflavin was sufficient to generate superoxide radicals reducing totally NBT. The activity of Cu/Zn-Sod is responsible to inhibit NBT reduction. Image analysis was performed after capture using UVP BioImaging Systems. The increase of Cu/Zn-Sod activity was determined, as percentage (%), by the ratio of total bands area of propolis (25 μg/mL 1 h) treated and non treated cells.

Determination of intracellular oxidation

The levels of intracellular oxidation were measured using the oxidant sensitive probe, 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. Fluorescence was measured using a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter at an excitation wavelength of 504 nm and an emission wavelength of 524 nm. As a control, fluorescence was recorded over 1 h at 40 °C without any cells and with cells previously killed (data not shown). A fresh 5 mM stock solution of probe dissolved in ethanol was added to the cell culture (to a final concentration of 10μM) and incubated at 28 °C to allow uptake of the probe. After 15 min, half of the culture was directly exposed to menadione (15 mM) while the other part was treated with propolis (25 μg/mL 1 h) and, thereafter, stressed with menadione. Cell extracts were prepared as previously described by Pereira et al. (2001) (Pereira et al., 2001). The results were expressed as a ratio between fluorescence of H2DCF in stressed and non-stressed cells during oxidative stress.

Data analysis

The results represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Statistical differences were tested using t-Test. The latter denotes homogeneity between experimental groups at p < 0.05. Different letters mean statistically different results. For lipid peroxidation assay we compared the homogeneity between stressed and non stressed cells of each strain at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Propolis protects S. cerevisiae cells against superoxide stress

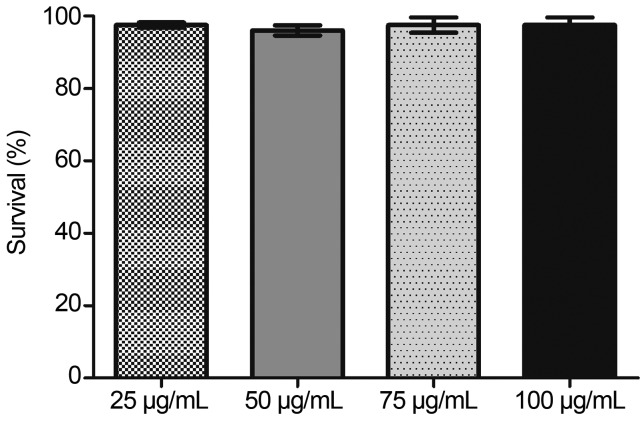

Propolis is recognized as an important pharmacologic substance. Among propolis properties, its antimicrobial action is the most studied and important (Boukraâ and Sulaiman, 2009; Sforcina and Bankovab, 2011). Firstly, we investigated if propolis treatment would kill S. cerevisiae cells. Thus, we directly exposed the wild type cells to propolis. Tolerance against propolis was measured after 1 h exposition. According to our results, treatment with propolis in the range of 25–100 μg/mL was not toxic for the wild type strain BY4741. Cells continued to reach 100% tolerance (Figure 1). Since cells were not affected by low doses of propolis we decided to study its protective role against oxidative stress. The antioxidant property of propolis was analyzed exposing S. cerevisiae cells, treated or not with propolis (25 μg/mL), to menadione (20 mM) or H2O2 (2 mM). Although menadione and H2O2 share similarities concerning genetic reprogramming, their mechanism of action and the stress factors involved in primary defense against these agents are quite distinct (Fernandes et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Survival of S. cerevisiae cells exposed to increasing propolis concentrations. Exponential cells of the wild type BY4741 were directly exposed to propolis. After 1 h, cells were plated in triplicate on solidified 2% YPD medium. The plates were incubated at 28 °C/72 h and then colonies counted. The results expressing percentage of survival in relation to non-stressed cells were obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

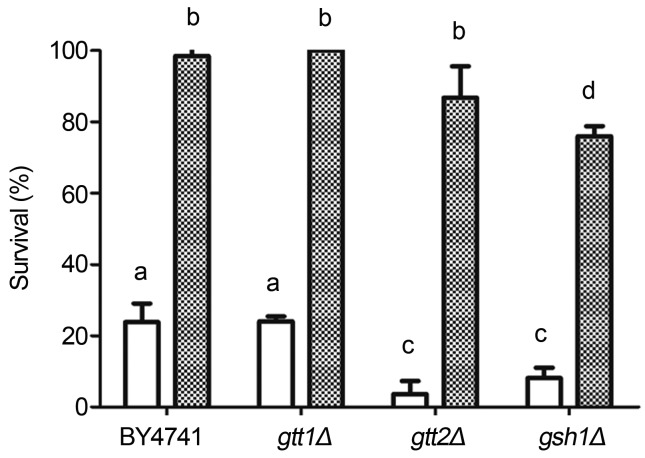

Menadione is a naphtoquinone used as an oxidative stress generator displaying strong ability to produce O2•− once inside the cells (Mauzeroll and Bard, 2004). In addition, as a mechanism of menadione elimination, a complex with glutathione (GSH) can also be formed through Gtt2 activity (Mauzeroll and Bard, 2004; Castro et al., 2007). Here, as we can see in Figure 2, cells deficient in the glutathione transferase Gtt1 (gtt1Δ) showed the same tolerance profile presented by the wild type. On the other hand, the Gtt2 deficient strain (gtt2Δ) was drastically affected by menadione stress. In spite of being hypersensitive to a direct exposure to menadione stress, this strain acquired tolerance after propolis treatment. In this scenario we are led to suggest that propolis administration is sufficient to overcome Gtt2 deficiency (Figure 2). GSH, γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine, is the main and multifunctional antioxidant encountered in all living cells (Hayes et al., 2005; Forman et al., 2009; Pallardó et al., 2009). In order to test whether the antioxidant potential of propolis could replace GSH, we decided to use a mutant of S. cerevisiae deficient in GSH synthesis (gsh1Δ). This strain presents a disruption in GSH1, which encodes the enzyme gamma glutamyl-cysteine synthetase involved in the first step of GSH synthesis. Despite the fact that cells were very sensitive to menadione stress, propolis treatment strongly increased survival of the gsh1 mutant (Figure 2). However, protection exhibited by 25 μg/mL propolis was not sufficient for cells to reach 100% survival (Figure 2). Indeed, full protection against menadione in strain gsh1Δ, was achieved after 50 μg/mL propolis treatment (data not shown). These results demonstrate that besides being very important for cellular protection against menadione stress, the deficiency in GSH is bypassed by propolis treatment, presumably due to components with antioxidant properties in the propolis extract.

Figure 2.

Effect of propolis treatment on cellular survival against menadione. Wild type (BY4741) and mutants strains gtt1Δ, gtt2Δ and gsh1Δ, harvested in mid exponential phase, were stressed with 15 mM menadione/1 h. Cells were directly stressed (white bars) or previously treated with 25 μg/mL propolis during 1 h before being exposed to menadione stress (hatched bars). The results expressing percentage of survival in relation to non-stressed cells were obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Different letters mean statistically different results.

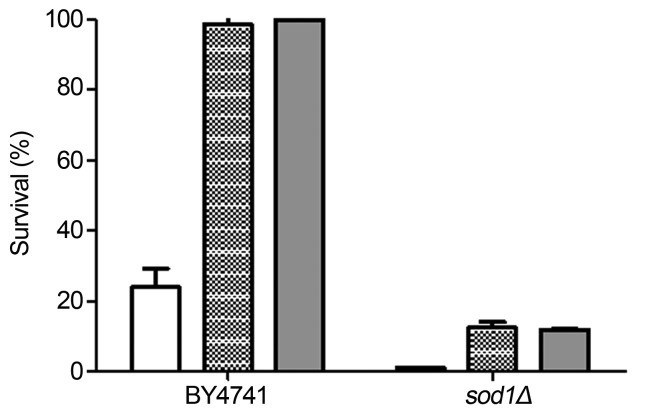

Superoxide dismutases (Sods) are very important metallo-enzymes involved in cellular protection against superoxide (O2•−) toxicity. Among Sods, Cu/Zn-Sod is designed as the first line of defense against O2•− toxicity and it is found in many of eukaryotic organelles (Bonatto, 2007; Abreu and Cabelli, 2010). Regarding to Mn-Sod function, located in mitochondria, it appears to be restricted to protect cells against O2•− radicals produced as by-products of respiration and/or other processes inside of mitochondria (Fridovich, 1995). Furthermore as already described yeast strains are highly damaged when SOD1 mutations are present (Wallace et al., 2005). Thus, in this work using a mutant strain of S. cerevisiae defective in Cu/Zn-Sod (sod1Δ) biosynthesis, we investigated whether propolis would still be able to protect sod1Δ cells after menadione stress. Menadione is a redox cycling agent reacting with cytoplasmic components generating O2•− radicals. Therefore the Cu/Zn-Sod must be essential in yeast response against this stress. As expected, the sod1Δ mutant strain was hypersensitive after menadione stress (Figure 3). Propolis treatment conferred small protection to the sod1Δ mutant, not sufficient to recover the hypersensitive phenotype of cells (Figure 3). Different from the data obtained with the gsh1Δ mutant, the increase of propolis concentration (50 μg/mL) did not improve sod1Δ tolerance (Figure 3). Taken together, our results with sod1Δ, suggest that propolis might be acting in synergy with Cu/Zn-Sod or, perhaps, activating this enzyme.

Figure 3.

Dependence of Cu/Zn-Sod for full protection after propolis treatment. Wild type and mutant strains, harvested in mid exponential phase, were stressed with 15 mM menadione/60 min. Cells were directly stressed (white bars) or previously treated with 25 μg/mL (hatched bars) or 50 μg/mL (gray bars) propolis during 1 h before being exposed to menadione. The results expressing percentage of survival in relation to non-stressed cells were obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Different letters mean statistically different results.

To test our hypothesis, the activity of Cu/Zn-Sod was assessed, as well as, whether propolis had the potential to activate the metal catalyzed reaction of Cu/Zn-Sod. After propolis treatment, a 63% (± 4.2) increase in Cu/Zn-Sod activity was observed in the wild type strain. That non-lethal menadione stress induces Cu/Zn-Sod activity has been previously described (Mannarino et al., 2011). We used the well defined menadione treatment (0.5 mM/60 min) as a reference for the increase in Cu/Zn-Sod activity. The activation of Cu/Zn-Sod, promoted by propolis, was higher than menadione, 63% (± 4.2) vs 50% (± 6.4). We can, therefore, conclude that sod1Δ did not acquire tolerance, as observed by the other strains, due to the impossibility of increasing Cu/Zn-Sod activity, which in fact is absent in the sod1Δ mutant. Contrasting with current results, Kanbur et al. (2008) (Kanbur et al., 2008) obtained in studies of the effect of propolis in drug protection, we did not detect any statistical differences in activity of the antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase when propolis was added to experimental groups. Here, we show the first evidence that propolis triggered the activation of Cu/Zn-Sod, one of the best characterized and most important antioxidant enzymes.

Biomarkers of oxidative stress are extremely useful in evaluating cytotoxicity. Among them, intracellular oxidation is one of the best characterized and explored biomarkers used to detect oxidative stress (Bartosz, 2006). In this work, using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) we determined the levels of intracellular oxidation during menadione stress. H2DCF-DA is a fluorogenic probe that can permeate the cell membrane by passive diffusion and is deacetylated by cytossolic esterases. H2DCF is more polar than the parent compound thus being trapped within the cell. Once inside the cell, it becomes susceptible to the attack by ROS, yielding a high fluorescent product (Bartosz, 2006). Recently, propolis from the Slovenian region was described as being able to reduce the levels of intracellular oxidation in cells (wild type) of S. cerevisiae (Tanja et al., 2011). The levels of intracellular oxidation were measured only in cells at stationary growth phase without any oxidative treatment. Curiously, although propolis did not increase cell viability, the authors stated that propolis also influences cell energy metabolism and protein patterns. In our approach, we decided to measure the levels of intracellular oxidation in S. cerevisiae cells exposed to lethal oxidative stress conditions. Direct exposure to menadione produced an increase of H2DCF fluorescence in the wild type strain and also in the sod1 mutant strains (Table 1). However, after propolis treatment, a reduction of H2DCF oxidation was observed in both strains, indicating a potent antioxidant property of propolis (Table 1). Unexpectedly, although it is easy to correlate the levels of intracellular oxidation with tolerance in the wild type, the reduction in intracellular oxidation in mutant sod1Δ, by the propolis treatment was not accompanied by acquisition of tolerance. This result confirms our hypothesis that propolis protected yeast cells by reducing the levels of ROS. However the activation of Cu/Zn-Sod was crucial for cellular adaptation and response to stress condition. Thus, propolis action might be related to components in propolis, which are able to activate the antioxidant enzyme Cu/Zn-Sod and also, presumably, by scavenging ROS during stress.

Table 1.

Effect of propolis treatment in reducing the levels of intracellular oxidation (ROS production) after menadione stress.

| Relative fluorescence | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Strains | Not treated | Treated |

| Wild type | 1.3a ± 0.1 | 0.8b ± 0.1 |

| sod1Δ | 2.2c ± 0.3 | 1.0b ± 0.2 |

The Wild type and sod1Δ strains were directly stressed with menadione (15 mM) or previously propolis treated (25 μg/mL) during 60 min before being stressed with menadione. The results expressing relative fluorescence were obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Different letters mean statistically different results.

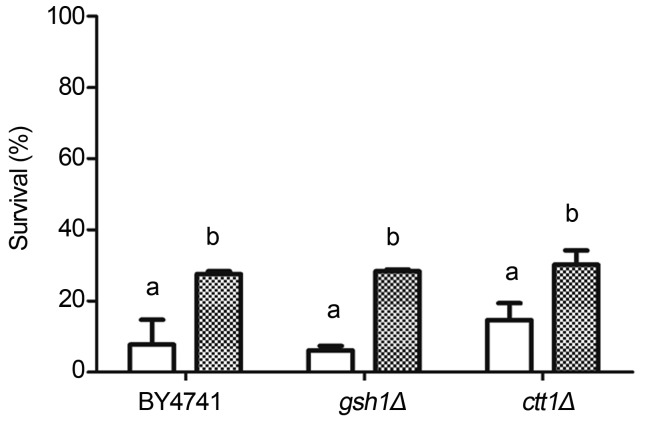

Cytotoxicity of H2O2 is also alleviated by propolis treatment

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is the most abundant reactive oxygen species in vivo, being continuously produced as a by-product of aerobic metabolism (Kakinuma et al., 1979). Changes in gene expression by H2O2 and O2•− involve similar targets, however, we have previously described that the cellular response to both conditions is quite distinct (Fernandes et al., 2007). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the response to H2O2 seems to be mainly related to the levels of GSH and to the activity of catalase (Ctt1) (Forman et al., 2009). In order to investigate the potential of propolis in protecting yeast cells against H2O2 stress we decided to perform experiments using the wild type strain and mutant strains harboring deficiency in either GSH or Ctt1 synthesis. According to Figure 4, cells were drastically affected by direct exposure to H2O2. However, after propolis treatment, survival increased almost 3 times. No significant differences were observed between strains, suggesting that propolis compensates deficiencies in both GSH and Ctt1.

Figure 4.

Effect of propolis treatment on cellular survival after exposure to H2O2. Wild type and mutants strains were harvested in the mid exponential phase and stressed with 2 mM H2O2 / 1 h. Cells were directly stressed (white bars) or previously treated with propolis (25 μg/mL) during 60 min before being exposed to H2O2 stress (hatched bars). The results expressing percentage of survival in relation to non-stressed cells were obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Different letters mean statistically different results.

Oxidative stress generated by H2O2 frequently induces oxidative damages in biomolecules such as lipid, proteins and DNA (Benaroudj et al., 2001; Hwang and Kim, 2007; Nery et al., 2008). However, a reduction in lipid and protein oxidation is observed in cells pre-adapted and subsequently exposed to H2O2 (Benaroudj et al., 2001; Fernandes et al., 2007; Nery et al., 2008; Dani et al., 2008). Here, lipid peroxidation was assessed by TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances) using exponential cells exposed or not to H2O2. Propolis treated cells exposed to H2O2 were also examined. As expected, exposure of cells to H2O2 increased dramatically the levels of lipid peroxidation (Table 2). In fact, high levels of lipid peroxidation are frequently associated with impairment of growth and survival of yeast cells treated with H2O2 (Benaroudj et al., 2001; Fernandes et al., 2007; Nery et al., 2008; Dani et al., 2008). Propolis treatment reduced lipid oxidation in all S. cerevisiae strains (Table 2). Despite reducing lipid peroxidation, propolis did not restore basal lipid peroxidation levels, suggesting that H2O2 was still exerting its toxic effect on cells (Table 2). This result is in accordance with the observed tolerance of cells which was not fully restored in cells treated with propolis. Protection of carps (Cyprinus carpio) from oxidative damages generated by chromium (VI) by propolis has been recently shown (Yonar et al., 2011). After 28 days of simultaneous administration of propolis and chromium, the levels of lipid peroxidation were decreased together with the increase in activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. Unfortunately, the author did not determine which isoform was involved in that activity.

Table 2.

Determination of lipid peroxidation in S. cerevisiae cells after H2O2 stress.

| H2 O2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Strains | Non stressed | Stressed | Propolis treated |

| Wild type | 59.6a ± 1.6 | 140.0b ± 6.0 | 111.7c ± 1.8 |

| gsh1Δ | 62.3a ± 3.2 | 183.4d ± 4.3 | 161.4e ± 2.7 |

| ctt1Δ | 46.7a ± 2.1 | 120.5c ± 6.5 | 92.2f ± 7.1 |

Lipid peroxidation was analyzed in exponential cells of the wild type and mutant strains after 2 mM H2O2. Non stressed, stressed (2 mM H2O2) and propolis treated cells were lysed by TCA 10% and extracts used to determine malondialdehyde (pmoles of MDA/mg of cell dry weight) levels. Lipid peroxidation data was obtained from the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Different letters mean statistically different results.

The Brazilian propolis used in this study is especially rich in phenolic acids contrasting with those originating from European and other temperate regions (Bankova et al., 1995; 2002). It was characterized the presence of caffeic acid, drupanin, p-coumaric acid, 3,4-dimethoxy-cinnamic acid, quercetin, pinobanksin 5-methyl ether, apigenin, kaempferol, pinobanksin, cinnamylideneacetic acid, chrysin, pinocembrin, galangin, pinobanksin 3-acetate, phenethyl caffeate, cinnamyl caffeate, tectochrysin, artepillin C (Marcucci et al., 2001, Souza et al., 2007). Recently, propolis and its components, caffeic and cinamic acid derivatives were shown to prevent oxidative damages in cell membranes and DNA (Benkovic et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2009). Artepillin C (3,5-diprenyl-4-hydroxycinamic acid), another phenolic substance found in large concentration in Brazilian propolis inhibited lipid peroxidation in different cell models (Shimizu et al., 2004). Souza et al. (2007), described that Brazilian propolis from Guarapari is largely composed by phenolic acids such as caffeic acid, drupanin (3-prenyl-4-hydroxycinamic acid), artepillin C and cinamic acid which might be acting as an antioxidant protecting yeast cells against H2O2 stress.

Conclusions

Based on these results we may conclude that propolis from Guarapari (Brazil) is a promissing antioxidant product due to three main reasons: (i) it contributes to protect membrane lipids from H2O2 stress; (ii) in response to an O2•− stress mediated by menadione, propolis acts maintaining the redox status by scavenging ROS and (iii) it activates Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase, one of the most important antioxidant enzymes.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from FAPERJ, CAPES and CNPq.

References

- Abreu IA, Cabelli DE. Superoxide dismutases - A review of the metal-associated mechanistic variations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankova V, Christov R, Kujumgiev A, Marcucci MC, Popov S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Brazilian propolis. Z Naturforsch C. 1995;50:167–172. doi: 10.1515/znc-1995-3-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankova V, Popova M, Bogdanov S, Sabatini AG. Chemical composition of European propolis: expected and unexpected results. Z Naturforsch C. 2002;57:530–533. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-5-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosz G. Use of spectroscopic probes for detection of reactive oxygen species. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368:53–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benaroudj N, Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Trehalose accumulation during cellular stress protects cells and cellular proteins from damage by oxygen radicals. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24261–24267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkovic V, Kopjar N, Horvat Knezevic A, Dikic D, Basic I, Ramic S, Viculin T, Knezevic F, Orolic N. Evaluation of radioprotective effects of propolis and quercetin on human white blood cells in vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1778. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonatto D. A systems biology analysis of protein-protein interactions between yeast superoxide dismutases and DNA repair pathways. Free Radical Biol Med. 2007;43:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouayed J, Bohn T. Exogenous antioxidants - Double-edged swords in cellular redox state: Health beneficial effects at physiologic doses vs. deleterious effects at high doses. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. 2010;1:228–237. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.4.12858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukraâ L, Sulaiman SA. Rediscovering the antibiotics of the hive. Recent Pat Anti-Infect Drug Discovery. 2009;4:206–213. doi: 10.2174/157489109789318505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FAV, Herdeiro RS, Panek AD, Eleutherio ECA, Pereira MD. Menadione stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains deficient in the glutathione transferases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani C, Bonatto D, Salvador M, Pereira MD, Henriques JAP, Eleutherio ECA. Antioxidant protection of resve-ratrol and catechin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:4268–4272. doi: 10.1021/jf800752s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski JW, Vohora SB, Sharma K, Shah SA, Naqvi SA, Dandiya PC. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiamoebic, antiinflammatory and antipyretic studies on propolis bee products. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes PN, Mannarino SC, Silva CG, Pereira MD, Panek AD, Eleutherio ECA. Oxidative stress response in eukaryotes: effect of glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase on adaptation to peroxide and menadione stresses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Rep. 2007;12:236–244. doi: 10.1179/135100007X200344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Caravaca AM, Gómez-Romero M, Arráez-Román D, Se-gura-Carretero A, Fernández-Gutiérrez A. Advances in the analysis of phenolic compounds in products derived from bees. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1220–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Flanangan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang ES, Kim GH. Biomarkers for oxidative stress status of DNA, lipids, and proteins in vitro and in vivo cancer research. Toxicol. 2007;229:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma K, Yamaguchi T, Kaneda M, Shimada K, Tomita Y, Chance B. A determination of H2O2 release by the treatment of human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes with myristate. J Biochem. 1979;86:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbur M, Atalay O, Ica A, Eraslan G, Cam Y. The curative and antioxidative efficiency of doramectin and dora-mectin+vitamin AD3E treatment on Psoroptes cuniculi infestation in rabbits. Res Vet Sci. 2008;85:291–293. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana V, Lindquist S. Modelling neurodegeneration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: why cook with baker’s yeast? Nat. Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:436–449. doi: 10.1038/nrn2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedhegner EAS, Gao XH, Mieyal JJ. Mechanisms of altered redox regulation in neurodegenerative diseases - Focus on S-glutathionylation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:543–66. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak VI. Adaptive response to oxidative stress: Bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. Comp Biochem Physiol C Comp Pharmacol. 2011;153:175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager WH, Winderickx J. Yeast as a model for medical and medicinal research. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarino SC, Vilela LF, Brasil AA, Aranha JN, Moradas-Ferreira P, Pereira MD, Costa V, Eleutherio ECA. Requirement of glutathione for Sod1 activation during lifespan extension. Yeast. 2011;28:19–25. doi: 10.1002/yea.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci MC, Ferreres F, García-Viguera C, Bankova VS, De Castro SL, Dantas AP, Valente PH, Paulino N. Phenolic compounds from Brazilian propolis with pharmacological activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;74:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauzeroll J, Bard AJ. Scanning electrochemical microscopy of menadione-glutathione conjugate export from yeast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7862–7867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402556101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morano KA, Grant CM, Moye-Rowley WS. The response to heat shock and oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2011 doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128033. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=10.1534%2Fgenetics.111.128033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nery DCM, Silva CG, Mariani D, Fernandes PN, Pereira MD, Panek AD, Eleutherio ECA. The role of trehalose and its transporter in protection against reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:1408–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallardó FV, Markovic J, García JL, Viña J. Role of nuclear glutathione as a key regulator of cell proliferation. Mol Asp Med. 2009;30:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MD, Eleutherio EC, Panek AD. Acquisition of tolerance against oxidative damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Microbiol. 2001;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad NR, Jeyanthimala K, Ramachandran S. Caffeic acid modulates ultraviolet radiation-B induced oxidative damage in human blood lymphocytes. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2009;95:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandalios JG. Oxidative stress: molecular perception and transduction of signals triggering antioxidant gene defenses. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38:995–1014. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforcina JM, Bankovab V. Propolis: Is there a potential for the development of new drugs? J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Ashida H, Matsuura Y, Kanazawaa K. Antioxidative bioavailability of artepillin C in Brazilian propolis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;424:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza RM, Souza MC, Patituci ML, Silva JFM. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities and characterization of bioactive components of two Brazilian propolis samples using a pKa-guided fractionation. Z Naturforsch C. 2007;62:801–807. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-11-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steels EL, Learmonth RP, Watson K. Stress tolerance and membrane lipid unsaturation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown aerobically or anaerobically. Microbiol. 1994;140:569–576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickland LH. The determination of small quantities of bacteria by means of the biuret reaction. J Gen Microbiol. 1951;5:698–703. doi: 10.1099/00221287-5-4-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanja C, Polak T, Gasperlin L, Raspor P, Jamnik P. Antioxidative Activity of Propolis Extract in Yeast Cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:11449–11455. doi: 10.1021/jf2022258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncola J, Cronin MTD, Mazura M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem & Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncola J, Izakovic M, Mazura M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;160:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos M, Ruiz-Navajas Y, Fernández-López J, Pérez-Álvarez JA. Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J Food Sci. 2008;73:117–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MA, Bailey S, Fukuto JM, Valentine JS, Gralla EB. Induction of phenotypes resembling CuZn-supero-xide dismutase deletion in wild-type yeast cells: an in vivo assay for the role of superoxide in the toxicity of redox-cycling compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1279–1286. doi: 10.1021/tx050050n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonar ME, Yonar SM, Çoban MZ, Eroglu MC. Antioxidant Effect of Propolis Against Exposure to Chromium in Cyprinus carpio. Environ Toxicol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/tox.20782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]