Abstract

Objectives

We examined the influence of prosocial orientations including altruism, volunteering, and informal helping on positive and negative well-being outcomes among retirement community dwelling elders.

Method

We utilize data from 2 waves, 3 years apart, of a panel study of successful aging (N = 585). Psychosocial well-being outcomes measured include life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect, and depressive symptomatology.

Results

Ordinal logistic regression results indicate that altruistic attitudes, volunteering, and informal helping behaviors make unique contributions to the maintenance of life satisfaction, positive affect and other well being outcomes considered in this research. Predictors explain variance primarily in the positive indicators of psychological well-being, but are not significantly associated with the negative outcomes. Female gender and functional limitations are also associated with diminished psychological well-being.

Discussion

Our findings underscore the value of altruistic attitudes as important additional predictors, along with prosocial behaviors in fostering life satisfaction and positive affect in old age.

Keywords: altruism, informal helping, volunteering, depression, life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect

It is well to give when asked, but it is better to give unasked, through understanding.

Khalil Gibran, 1923 (p. 20)

Introduction

As social roles are lost in late life, opportunities to engage in prosocial, contributory activities afford a promising avenue for maintaining life satisfaction and psychological well-being (Morrow-Howell, 2010). Furthermore, attitudinal expressions of compassion and good will toward others can also serve as expressions of generativity that promote meaningfulness and well-being in late life (Erikson, 1968). This research explores the impact of altruistic attitudes, informal helping, and volunteering on diverse indicators of well-being among retirement community dwelling elders. This research aims to move beyond prior emphasis on behavioral manifestations of prosocial orientations, by also paying attention to altruistic attitudes that are likely to motivate helping and volunteering. Thus, our study makes a unique contribution by presenting a multidimensional exploration of both dispositional and behavioral manifestations of altruism and also by considering alternative positive and negative well-being outcomes in a longitudinal framework. It has been argued that gerontological research must move beyond dependency, autonomy, and exchange-based models of old age and include contributory orientations to late life (Kahana, Midlarsky, & Kahana, 1987; Midlarsky & Kahana, 2007). The present study explores empirical evidence regarding such expectations.

Altruistic Attitudes

Altruistic attitudes comprise an important component of altruistic orientations, one that is not dependent on personal, material, or social resources that might decline in old age (Kahana & Kahana, 2003). Prior work utilizing cross-sectional data on older adults indicates that altruistic attitudes are prevalent among the elderly and that an association exists between altruistic attitudes and helping behaviors (Midlarsky & Kahana, 1994). However, the association between altruistic attitudes and psychological well-being outcomes has not been previously explored using longitudinal data. Altruistic attitudes refer to other-oriented concerns or compassion that is motivated by generativity (Erikson, 1968), by concern for the welfare of others (Dovidio, Piliavin, Schroder, & Penner, 2006), and by need for meaningful human connectedness even close to the end of life (Kahana et al., 2011).

Elements of altruistic orientations have been incorporated in the definition of agreeableness, one of the Big Five personality dimensions (Costa & McCrae, 1995). The potential mental health benefits of altruistic attitudes to those who hold them have been acknowledged (Midlarsky & Midlarsky, 2004; Rushton, Chrisjohn, & Fekken, 1981). Focus on other-oriented views of the self in old age is also consistent with conceptualizations of vital involvement in the world (Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1994) and gerotranscendence (Tornstam, 2007) during the final stage of life. Thus, it is important to examine the separate contributions of altruistic attitudes as well as prosocial behaviors to psychological well-being among the aged.

Volunteering

Volunteering comprises the most widely researched behavioral manifestation of prosocial orientations in late life. Older adults frequently provide services to the wider community through volunteer and charity work (Wilson, 2000). With the aging of the Baby Boom generation there will be greater numbers of older adults seeking meaningful civic engagement through volunteering (Seaman, 2012). Social, physical, psychological, and financial resources enable engagement in helping behaviors in late life (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Some elderly persons lack such resources, and this is reflected in their lower rates of volunteering (Choi, 2003). Gerontologists have recognized the salutary potential of volunteer activities for enhancing the quality of late life (Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario, & Tang, 2003). A major value of helping behaviors relates to their potential for building social capital in late life (Cornwell, 2011). The mental health benefits of engagement in formal volunteer behaviors in late life have also been extensively documented (Musick & Wilson, 2008). Longitudinal studies provide evidence that proso-cial behaviors, such as volunteering contribute to subsequent psychological well-being (Li & Ferraro, 2005; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Notably, however, recent evidence points to potential adverse effects of very high levels of volunteering in late life that places excessive demands on elders (Windsor, Anstey, & Rodgers, 2008).

Informal Helping

Provision of help by the elderly is also prevalent in the nonfamilial residential context. Elderly friends and neighbors tend to help each other in diverse ways, ranging from advice and social support to daily chores (Riche & Mackay, 2010). Voluminous research has documented the value of receiving help as a core component of social support, but there has been far less focus on benefits of providing informal help to the person who is offering help or support to others. While there has been less research focusing on the value of assisting others in informal settings, the giving of informal support has been found to be more beneficial in later life than receiving support (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003). Findings based on the national Changing Lives in Retirement study revealed that 5-year mortality was significantly reduced for married older adults who reported giving instrumental support to family, friends, or neighbors and those who provided emotional support to their spouse (Fowler & Christakis, 2008). Receiving support had no significant impact on mortality, once giving support was controlled for.

Prosocial behaviors in an informal context have been found to be both prevalent and salient among the elderly (Midlarsky & Kahana, 2007). Older persons are providers as well as recipients of financial assistance in the family context and also provide care to family members facing major illness (Fingerman, Pillemer, Silverstein, & Suitor, 2012). In difficult circumstances, when adult children are deceased, disabled, or absent from the home (e.g., in the military, in prison), older adults may become “skipped generation care-givers” to their grandchildren (Hayslip & Kaminsky, 2005; Kropf & Yoon, 2006).

Linking Altruistic Attitudes and Prosocial Behaviors to Components of Psychological Well-Being

Building on orientations of positive psychology (Seligman, 2002), in this study, we focus on the impact of altruistic attitudes and prosocial behaviors on psychological well-being outcomes (i.e., positive affect; life satisfaction) along with more traditional negative indicators (i.e., negative affect; depressive symptomatology). Psychological well-being entails experiencing high levels of pleasant or positive emotions accompanied by low levels of negative emotions (Diener & Oishi, 2005). While high-positive and low-negative affect are components of psychological well-being, these two constructs are distinct and have different external and personality correlates (Watson, 2005). Antecedents of negative affect have been more extensively studied than those of positive affect. Stressful life events and limited external and internal resources are viewed as contributing to psychological distress (Folkman, 2010). Positive affective states have been described as trait-like. Nevertheless, active and goal-directed engagement with the social and physical environment has been found to enhance positive affect (Watson, 2005). Furthermore, prior research supports expectations that altruistic attitudes and behaviors contribute to existential well-being outcomes such as valuation of life and life satisfaction (Lawton, Moss, Winter, & Hoffman, 2002).

Prosocial orientations may exert salutary effects through multiple mechanisms, ranging from enhancing a sense of “mattering” (Fazio, 2009) to promoting positive role identities (Piliavin, 2009). Generativity has been proposed as a key developmental task of aging (Antonovsky & Sagy, 1990; Erikson et al., 1994). Altruistic attitudes and helping behaviors offer important expressions of generativity. Helping behaviors may also be viewed as proactive adaptations that contribute to positive outcomes even in the face of the normative stressors associated with aging (Kahana & Kahana, 2003; Kahana, Kelley-Moore, & Kahana, 2012). Such proactive behavioral adaptations may foster self-efficacy and can complement altruistic attitudes, thereby contributing to the maintenance of psychological well-being in late life.

The present study takes a necessary next step toward examining the contributions of altruistic attitudes, volunteering, and informal helping behaviors to psychological well-being in late life. Explicit attention is needed to linking altruistic attitudes and prosocial behaviors to positive versus negative affect and to existential well-being outcomes, such as life satisfaction. We address important gaps in the literature related to longitudinal research that simultaneously considers altruistic attitudes, volunteering, and informal helping, as they contribute to a multidimensional understanding of psychological well-being in late life (George, 2010). We hypothesize that altruistic attitudes, informal helping, and volunteering at earlier time points will contribute to enhancing positive affective states and life satisfaction and will aid in diminishing negative affective states and depressive symptomatology at later points in time.

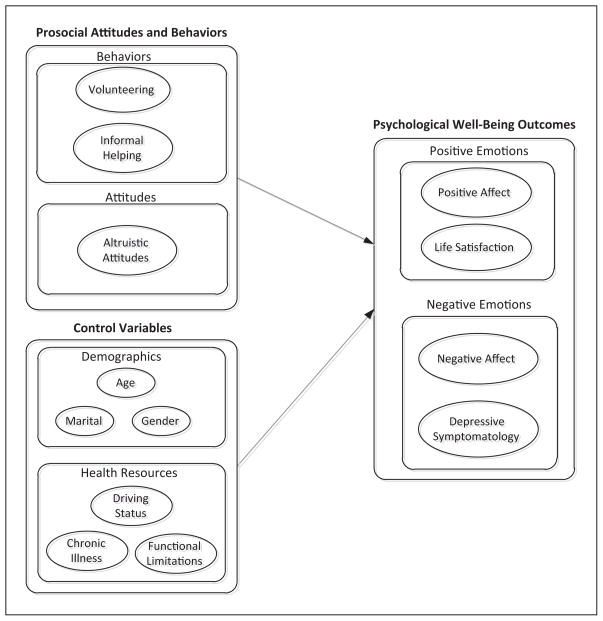

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized linkages in our study. Our model reflects expectations that prosocial orientations (reflected in altruistic attitudes, volunteering, and informal helping) will influence both positive and negative indicators of psychological well-being. The model also depicts key demographic and health-related influences on psychological well-being. Accordingly, we recognize that women are more likely to show depressive symptomatology than are their male counterparts (Blazer, 2005). Furthermore, older age has been found to be associated with diminished affect, both positive and negative (Charles, Reynolds, & Gatz, 2001).

Figure 1.

Contributory Model of Psychological Well-Being in Late Life: The Role of Volunteering, Informal Helping and Altruistic Attitudes

Married elders are more likely to demonstrate positive affect and life satisfaction than are unmarried elders (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999). In terms of health-related resources, chronic illnesses and functional limitations have been consistently associated with reduced psychological well-being (Schnittker, 2005). Driving cessation is also considered a relevant functional health-related variable that is likely to limit older adults’ ability to volunteer, and to offer informal help to others, and that may also adversely impact their affective states (Choi, Adams, & Kahana, 2012). We thus anticipate that both health-related resources and demographic characteristics will exert an influence on positive and negative affective states. Consequently, in our analyses we control for relevant demographic and health-related characteristics as we examine altruism and psychological well-being linkages. We note that the aim of this initial study is to establish linkages between altruistic attitudes, helping behaviors, and psychological well-being. We thus try to establish the linkages among the phenomena explored before understanding underlying processes (Merton, 1987).

Our study seeks a better understanding of the relationship between diverse components of altruistic attitudes, helping, and the maintenance of psychological well-being in late life. We refer to the model depicting these expectations as the contributory model of psychological well-being in late life.

Method

Sample

Data for this research are part of the long-term longitudinal study of successful aging conducted by the Elderly Care Research Center (Kahana et al., 2002, 2012, 2003; Kelley-Moore, Schumacher, Kahana, & Kahana, 2006; Zhang, Kahana, Kahana, Hu, & Pozuelo, 2009). We utilize data from two waves of panel study, 3 years apart (Waves 2 and 5). These waves were selected based on the availability of data on variables of interest, and on having a sufficient time lapse for examining the hypothesized influences, and retaining a maximum sample size for the analyses. The panel study had annual in-person follow-ups, which focused on late-life adaptation of retirement community dwelling elders (Kahana et al., 2012).

The large retirement community that is the source of our sample is situated on the West Coast of Florida. This residential setting was designed to attract active, healthy older adults and does not offer any support services (e.g., meals and housekeeping). Participants resided in condominiums, most of which were one bedroom units in three-story buildings, without elevators. Respondents generally migrated after retirement from the Midwest, and most lived dispersed from their extended families. A total of 3,905 households were randomly selected from residential listings of the retirement community. Selected households were contacted by telephone to determine if a member of the household met eligibility criteria (see Kahana et al., 2002). Eligibility criteria included (a) age 72 years or older at baseline, (b) living in Florida at least 9 months out of the year, and (c) reporting that they were “sufficiently healthy” to complete a 90-min face-to-face interview. Of the 3,905 households contacted, 48.9% (n = 1,909) did not meet eligibility criteria.

At the onset of the study, 1,000 respondents, representing 908 households completed an in-home, face-to-face interview. Interviews were conducted in respondent’s homes by trained interviewers after obtaining informed consent. The structured interview was of 60 to 90 minutes duration. The response rate for those approached and invited to participate in the Florida Retirement Study at baseline was 77.3%. Death was the primary source of attrition for this sample. Indeed, loss to follow-up for other reasons (e.g., moving with no forwarding address or loss of interest in study participation) accounted for only 7% of annual attrition. The effective N for participants who completed both Waves 2 and 5 interviews was 585. Findings indicate that respondents who died or dropped out by Wave 5 were significantly older, more functionally impaired and less likely to volunteer (p < .05) at Wave 1. No differences were found in terms of gender or marital status between the original sample and those respondents remaining in Wave 5.

Measurement

We used four psychological well-being outcomes as our dependent variables: life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect, and depressive symptomatology. Our choice of dependent variables reflects our quest for comprehensiveness and specificity. An important, person-centered definition of happiness includes cognitive evaluation of one’s life as a whole, which is termed life satisfaction (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006). Sustainable happiness models recognize that cognitive as well as behavioral goal-seeking activities (such as altruistic orientations) can contribute to psychological well-being (Sheldon & Elliott, 1999). Although life satisfaction tends to correlate positively with positive affect and negatively with negative affect, such correlations are generally not very high (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2007). Major longitudinal studies of psychological well-being in social psychology consider life course progression in life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect and identify age-related changes in these outcomes (Diener et al., 2006). These studies indicate that different well-being outcomes change in diverse ways along the life course, with changes in one domain diverging from changes in others.

All outcomes were assessed at two time points: Waves 2 and 5. It should be noted that based on the analytic requirements of our ordinal logistic regression models we converted summated scores on our outcome measures to their original scaled scores.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured by using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, & Griffin, 1985). Respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale their agreement with five statements related to life satisfaction (e.g. “In most ways my life is close to ideal”). Responses across items were summed and divided by five (to preserve the response metric of the original variables) in order to construct a score. Exploratory factor analysis yielded a strong fit on a single factor indicating a single construct at both waves (α = 0.78 at Wave 2; α = 0.80 at Wave 5).

Positive and negative affect

Positive and negative affects were measured using the PANAS scale (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The PANAS consists of 10 words that describe different emotions. Five words describe positive affect (e.g., happy, alert) and five items describe negative affect (e.g., afraid, nervous). Respondents were asked to report on a 5-point scale, the extent to which they had felt specified emotions during the past year. Two scales were created (positive and negative affects), by summing responses across items and dividing that score by 5, with a higher score for each affect scale reflecting greater affect levels.

Depressive symptomatology

Depressive symptoms were measured with the 10-item short version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). A series of questions inquires about frequency of feeling specific emotions (e.g. “had the blues”), with responses ranging from (1) rarely or never to (4) always. Items were summed and divided by 10 to create a single score ranging from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptomatology. Since only 8 of the 585 respondents in our sample endorsed “always” experiencing symptoms on all items, we recoded the scale to reflect the observed distribution of scores, limiting its range to 3 (i.e., the eight respondents reporting scores of 4 were top-coded as 3). This improved the model fit (i.e., significant reduction of log likelihood from 984.094 to 923.13).

Predictors

Our choice of independent variables was based on a desire to explore major indicators of prosocial orientations in both the behavioral and attitudinal domains. Within the field of gerontology, volunteering serves as the prototype of engagement in prosocial actions and is the most widely studied construct in its domain (Morrow-Howell, 2010). Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) argues that when prosocial behaviors are volitional, well-being outcomes of the helper are likely to be enhanced (Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). Volunteering exemplifies this genre of autonomous behavior. Inclusion of informal help provided to friends and neighbors allows for examination of less frequently studied forms of helping that may be responsive to requests for help by significant others. Finally, focus on altruistic attitudes enables us to consider the impact of value systems reflecting empathy and concern for others without behavioral expressions of such concerns (Post, 2005). We thus explore a broad spectrum of prosocial orientations characterizing older adults as they relate to psychological well-being outcomes.

Altruistic attitudes

We utilized a four-item Elderly Care Research Center (ECRC) altruism scale developed for this study to assess altruistic attitudes since no previously validated scales of altruistic attitudes for use with older adults were available. Furthermore, existing measures (e.g., Rushton et al., 1981) typically considered self-reports of engagement in helping behaviors, rather than attitudinal dimensions of the construct. At Wave 2, respondents were asked on a 5-point Likert-type scale to what extent they agreed with four statements. Items include: (1) “I come first and should not have to care so much for others;” (2) “In this day and age, it doesn’t make sense to help out someone in trouble;” (3) “I enjoy doing things for others;” and (4) “I try to help others, even if they do not help me.” Two of the four items were reverse coded so that a higher score reflects more altruistic attitudes. All items were summed and divided by 4 to create a single score ranging from (1) to (5), with higher scores indicating more altruistic attitudes.

Given the relatively small number of items measuring altruistic attitudes, this scale has acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.66). The number of items is a major determinant of Cronbach’s α estimate, because an increase in number of items can, independent of other factors, improve Cronbach’s α estimate (Cortina, 1993). Exploratory factor analyses revealed a single factor with factor loadings greater than 0.40 and that factor explained 49.8% of the total variance (Eigen value = 1.992). Validation of the ECRC altruism scale included convergent validity and discriminant validity. With respect to convergent validity, we found a significant correlation between our ECRC altruism scale and agreeableness, a personality disposition (McCrae & Costa, 1987). With respect to discriminant validity, a significant inverse correlation was found with self-reported enviousness, an aspect of personality that reflects an absence of altruistic attitudes (Greenleaf, 2009).

Frequency of volunteering

The frequency of volunteering was measured by asking respondents about the amount of time they committed to volunteering per week. Respondents were asked: “On average, how many hours per week do you volunteer?” Responses ranged from “no volunteering” to “45 hours” of volunteering per week. However, most of the responses fall in the 0 to 14 hour range comprising 97.4% of total responses. It should be noted that we did not find a curvilinear relationship between volunteering and well-being outcomes (Windsor et al., 2008).

Informal helping behavior

Informal helping was measured at baseline (Wave 2) with five items assessing how much instrumental support the respondent provided to friends and neighbors over the past year. Examples of helping behaviors include: assistance with transportation, shopping, and errands. The responses on five items were summed, divided by five (to retain the response metric), creating a composite score ranging from (1) none to (5) very much.

Control Variables

Demographic characteristics

Respondents’ gender, age, and marital status were included in the analyses as potential predictors of psychological well-being and were measured by standard interview questions. Age was measured in years and ranged from 72 to 98 years. Marital status was measured as a dichotomous variable (married versus not married). The preponderance of unmarried respondents in this sample were widowed (89.8%).

Driving status

Driving status was measured by asking respondents if they were currently driving. This was included because driving may potentially facilitate participation in volunteer activities (Warburton, Terry, Rosenman, & Shapiro, 2001).

Chronic illness

Chronic illness was measured by The Older Americans Resource Study (OARS) Illness Index (George & Fillenbaum, 1985). Responses to the OARS indicate whether respondents had specific, diagnosed illness conditions during the prior year. Examples of the 12 illnesses are arthritis, diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. The total score for each respondent was obtained by summing all reported illness conditions (possible range 0 to 12).

Functional limitations

Functional limitations were measured by the nine-item OARS activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) index (Fillenbaum, 1988). To assess IADL levels, respondents were asked three questions reflecting their difficulty with carrying out household activities (e.g., doing one’s own housework). ADL functioning was assessed through the use of six questions regarding trouble with personal tasks such as washing and bathing. A functional limitation scale was created by summing across the nine items (and then dividing by 9). This resulted in a possible range of 1 to 4, with a higher score reflecting greater functional difficulty. Given that there were only 10 respondents with a score higher than 2, we dichotomized the functional limitation scale to distinguish those with no functional limitations from those with any limitations. This also enhanced the model fit.

Analytical Plan

We employed ordinal logistic regression to examine the relationship between altruistic attitudes, prososcial behaviors and psychological well-being outcomes. Ordinal logistic regression is best suited to our data as it do not assume equivalence of intervals between any two given points on a scale. Such equivalence is necessary to meet the assumption of a multiple linear regression as the analytical framework. Given the ordinal nature of our outcome variables, ordinal logistic regression provides us with more efficient regression estimates. In addition, the use of ordinal logistic regression yields unbiased parameter estimates when an outcome variable is highly skewed (Agresti, 2002).

A hierarchical approach was taken to examine the unique contribution of each separate set of variables that were selected due to their substantive importance. In Model 1, the prosocial behaviors and altruistic attitudes were entered to examine whether these key predictors significantly influence psychological well-being outcomes. In Model 2, demographic and health resource variables were entered in the model, due to their confounding influence on the relationship between the altruistic attitudes, prosocial behaviors and psychological well-being outcomes. We also controlled for outcome variables at baseline. A hierarchical approach to statistical modeling allows us to assess whether this set of variables uniquely contributes to better model fit. For example, in case of negative affect, prosocial behaviors do not contribute to a better model fit, suggesting their irrelevance to the overall model (i.e., log likelihood increased from 1105.76 to 1108.60). We would not have observed this finding had we simultaneously included all variables in the model.

Each model was adjusted for nonrandom attrition using a hazard rate instrument based on the inverse Mills ratio. This expresses the likelihood of not remaining in the study for all four waves (Heckman, 1979). A probit equation estimates the likelihood of completing all four waves of the study. Based on that likelihood, an inverse Mills ratio is calculated for each case so that high values reflect a strong likelihood of not completing the study. This variable is entered into the model as a covariate (Beck, 1983).

The proportional odds assumption of the ordinal logistic model was tested for all four psychological well-being outcomes to examine whether the parameter estimates were the same across all response categories. Nonsignificant p values indicate that this assumption was not violated (the p value from final models for life satisfaction, negative affect, positive affect, and depressive symptoms = 0.857, 0.589, 0.257, and 0.769, respectively).

The interactive influence of altruistic attitude and prosocial behavior variables on psychological well-being was also examined. The findings of that analysis are not presented, as the inclusion of interaction terms did not increase the model fit and their influence on psychological well-being was not statistically significant.

Results

Study results are organized in two sections. First, a descriptive overview of study variables is presented, followed by a summary of the four individual regression models describing the effects of altruistic attitudes and prosocial behaviors, after controlling for demographic characteristics and health status on psychological well-being.

Demographic, Health and Mobility Characteristics

The descriptive statistics for the sample included in the analysis are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (66%). The mean age of the sample at Wave 2 was 79.7 years. Close to half of respondents, 47.2% were married and 46.5% were widowed. Only 6.3% were never married, divorced, or separated. Participants reported on average 1.89 illness conditions (possible range 0 to 12) and IADL/ADL difficulty of 1.08 (range = 1 to 4). Most of the respondents (at Wave 2) reported that they currently drive a car (81%).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Coding for Variables in the Conceptual Model.

| Variable name | Coding scheme | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) W2 | Range 72 to 98 | 79.7 | 4.41 | — |

| Female | 1 = Female; 0 = Male | 0.66 | ||

| Marital status W2 | 1 = Married; 0 = Not married | 0.47 | ||

| Health resource variables | ||||

| Driving status W2 | 1 = Drive; 0 = Doesn’t drive | 0.81 | ||

| Chronic illness W2 | Range 0 to 12 | 1.89 | 1.31 | |

| Functional limitation W2 | Range 1 to 4 | 1.08 | 0.23 | |

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors | ||||

| Altruistic attitudes W2 | Range 1 to 5 | 4.16 | 0.51 | 0.66 |

| Volunteer W2 | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.43 | ||

| Hours of volunteering W2 | Range 0 to 45 | 2.40 | 4.28 | |

| Informal helping W2 | Range 1 to 5 | 1.70 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| Psychological well-being | ||||

| Positive affect W2 | Range 1 to 5 | 3.3 | 0.81 | 0.73 |

| Negative affect W2 | Range 1 to 5 | 1.75 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Depressive symptomatology W2 | Range 1 to 4 | 1.80 | 0.63 | 0.83 |

| Life satisfaction W2 | Range 1 to 5 | 3.71 | 0.65 | 0.78 |

| Positive affect W5 | Range 1 to 5 | 3.05 | 0.88 | 0.80 |

| Negative affect W5 | Range 1 to 5 | 1.83 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| Depressive symptomatology W5 | Range 1 to 4 | 1.93 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| Life satisfaction W5 | Range 1 to 5 | 3.65 | 0.64 | 0.80 |

Note. The standard deviation is not reported for binary variables (i.e., female, marital, and driving status). W2 = Wave 2; W5 = Wave 5; effective n = 585.

Additional relevant background characteristics regarding the sample are noted below. All study respondents were Caucasian. In terms of religious affiliation, 69% of respondents were Protestant, 20% were Catholic with 6% Jewish, and the remainder (5%) were comprised of other other or unaffiliated.

In terms of religious activity, almost half of the respondents attended church every week. Reflecting marital status, 51.4% lived alone, 2.5% lived with other relatives, and 1.3% lived with nonfamily. In terms of educational background, 12.9% reported less than a high school education, 27.7% were high school graduates, and the remainder had at least some college training. Most of the respondents participating in our study were of modest financial means: 10.1% of the sample reported an annual income (before taxes) below US$10,000, 35.8% reported an income between US$10,000 and US$19,000, 39.4% reported an income between US$20,000 and US$29,000 per year. Only 14.7% reported an income of over US$40,000 per year. In terms of work status, 80.3% were retired, 3.1% were working part-time, and 16.6% never worked for pay.

Descriptive Results

Respondents reported high levels of altruistic attitudes, with a mean score of 4.16 (range of 1 to 5; see Table 1). Forty-three percent of participants reported that they had engaged in volunteer activities with respondents reporting an average of 2.40 hours of volunteering (range = 0 to 45). The mean score for providing informal help to friends and neighbors was 1.70 (range = 1 to 5). Assistance with transportation (65.5%) was the most prevalent type of help provided by respondents, with nearly one fifth stating that they provided “much” or “very much” of this type of assistance to others. Shopping and helping with household tasks were additional helping tasks in which respondents engaged, albeit at lower levels. Just over one half (55.9%) reported helping others with shopping and one fifth reported helping with household tasks. Few respondents (10%) assisted friends and neighbors with personal care tasks. The correlation between volunteering and informal help was 0.253 (p < .01), whereas the correlation between volunteering and altruistic attitudes was 0.261 (p < .01). Similarly, the correlation between altruistic attitudes and informal helping was 0.257 (p < .01). Weak, but statistically significant correlation coefficients suggest some degree of overlap among various indicators of prosocial activities and orientations, implying that respondents participating in one prosocial activity may also engage in other prosocial activities.

Regarding psychological well-being at Wave 2, participants reported a mean life satisfaction score of 3.71 (possible range = 1 to 5), a mean positive affect score of 3.31 (possible range = 1 to 5), a mean negative affect score of 1.75 (possible range = 1 to 5), and a mean depressive symptoms score of 1.80 (possible range = 1 to 4). Mean scores at Wave 5 for the psychological well-being outcomes were 3.65 for life satisfaction, 3.05 for positive affect, 1.83 for negative affect, and 1.93 for depressive symptoms. The t-test performed to examine mean change in positive affect (p < .001) and life satisfaction (p < .05) between two waves indicates a statistically significant decline in both positive emotional states. In contrast, the findings reveal a small, but statistically significant increase in one negative emotional state (i.e., depressive symptoms; p = .001).

Multivariate Results

Tables 2 to 5 show the ordinal logistics regression results for each of the four psychological well-being domains. The results for the two positive well-being outcomes are presented first (i.e., positive affect; life satisfaction), followed by the two negative domains (i.e., negative affect; depressive symptomatology).

Table 2.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results for Positive Affect Outcome

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors | ||||

| Altruistic attitudes W2 | 0.843*** | 0.188 | 0.465* | 0.200 |

| Hours of volunteering W2 | 0.055** | 0.020 | 0.042* | 0.021 |

| Informal helping W2 | 0.484*** | 0.133 | 0.401** | 0.145 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | −0.023 | 0.189 | ||

| Age W2 | −0.066*** | 0.020 | ||

| Marital status W2 | 0.163 | 0.177 | ||

| Positive affect W2 | 1.082*** | 0.115 | ||

| Health-related resources | ||||

| Driving status W2 | −0.029 | 0.230 | ||

| Functional limitation W2 | −0.528* | 0.221 | ||

| Chronic illness W2 | −0.016 | 0.065 | ||

| Mortality λ | 0.055 | 0.344 | 0.265 | 0.357 |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 1354.50(4) | 1251.73(11) | ||

Note. b = Slope estimate; SE = standard error; df = degree of freedom; W2 = Wave 2; W5 = Wave 5; effective n = 585.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results for Depressive Symptomatology Outcome

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors | ||||

| Altruistic attitudes W2 | −0.295 | 0.196 | −0.206 | 0.208 |

| Hours of volunteering W2 | −0.059** | 0.021 | −0.065** | 0.022 |

| Informal helping W2 | −0.308* | 0.140 | −0.231 | 0.155 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | 0.877*** | 0.209 | ||

| Age W2 | 0.037 | 0.021 | ||

| Marital status W2 | 0.087 | 0.193 | ||

| Depressive symptoms W2 | 1.160*** | 0.159 | ||

| Health-related resources | ||||

| Driving status W2 | 0.170 | 0.248 | ||

| Functional limitation W2 | 0.824*** | 0.243 | ||

| Chronic illness W2 | 0.128 | 0.071 | ||

| Mortality λ | 0.317 | 0.364 | 0.136 | 0.393 |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 1030.93(4) | 923.13(11) | ||

Note. b = slope estimate; SE = standard error; df = degree of freedom; W2 = Wave 2; W5 = Wave 5; effective n = 585.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Positive Affect

Table 2 presents the analysis of factors predicting positive affect. As depicted in Model 1, we find that altruistic attitudes (p < .001), frequency of volunteering (p = .006), and informal helping (p < .001) emerge as statistically significant predictors of positive affect at Wave 5. These findings demonstrate a significantly greater ordered log odds (0.843 for altruistic attitudes, 0.055 for frequency of volunteering, and 0.484 for informal helping) of respondents reporting higher positive affect at Wave 5. This establishes the influence of altruistic attitudes and prosocial behaviors on respondents’ psychological well-being.

The second model demonstrates that after controlling for demographic characteristics and health-related resources, all three prosocial variables remained significant predictors of positive affect, further establishing the salience of prosocial behaviors on positive affect. In addition, we found that respondents who were younger (p < .001) and had fewer functional limitations (p = .017) had higher degrees of positive affect. As expected, positive affect at Wave 2 emerged as a significant predictor of positive affect at Wave 5 (p < .001), indicating higher positive affect at Wave 5 for respondents who reported higher positive affect at Wave 2.

Life Satisfaction

Multivariate results for the life satisfaction outcome are shown in Table 3. In Model 1, results indicate that volunteering (p = .021) and informal helping (p = 0.045) at Wave 2, significantly influences life satisfaction at Wave 5. As such, respondents reporting higher frequency of volunteering and providing informal help to others have greater ordered log odds of reporting higher life satisfaction at Wave 5.

Table 3.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results for Life Satisfaction Outcome

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors | ||||

| Altruistic attitudes W2 | 0.333 | 0.213 | 0.048 | 0.232 |

| Hours of volunteering W2 | 0.058* | 0.025 | 0.061* | 0.026 |

| Informal helping W2 | 0.320* | 0.160 | 0.368* | 0.177 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | −0.498* | 0.232 | ||

| Age W2 | 0.009 | 0.024 | ||

| Marital status W2 | −0.093 | 0.214 | ||

| Life satisfaction W2 | 1.458*** | 0.164 | ||

| Health-related resources | ||||

| Driving status W2 | −0.450 | 0.280 | ||

| Functional limitation W2 | −0.685** | 0.251 | ||

| Chronic illness W2 | −0.202** | 0.077 | ||

| Mortality λ | −0.359 | 0.390 | −0.151 | 0.414 |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 908.05(4) | 797.26(11) | ||

Note. b = slope estimate; SE = standard error; df = degree of freedom; W2 = Wave 2; W5 = Wave 5; effective n = 585.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In Model 2, when controlling for demographic and health-related resources, we find that all prosocial variables that, were significant in Model 1 remain significant in Model 2. This finding highlights the persistent positive impact of prosocial behaviors on life satisfaction. Furthermore, gender (p = .032), functional limitations (p = .006), and chronic illness (p = .009) were found to be significantly related to life satisfaction. The ordered log odds of a woman reporting higher life satisfaction is 0.498 less than that of her male counterpart after controlling for the influence of other predictors in the model. Having a greater number of chronic illnesses and functional limitations at Wave 2 is predictive of lower life satisfaction at Wave 5. In addition, prior life satisfaction (at Wave 2) was a significant predictor of Wave 5 life satisfaction (p < .001).

Negative Affect

Results for negative affect are displayed in Table 4. In Model 1, the prosocial variables did not significantly predict negative affect. After we entered the demographic and health-related control variables in Model 2, altruistic attitudes and prosocial behavior remained nonsignificant. Of the health-related controls, only functional limitation emerged as a significant predictor (p = .024) of negative affect, reflecting a higher ordered log odds (i.e., 0.503 points higher) of negative affect at Wave 5 for people reporting greater functional limitations . Of the three demographic predictors, only gender was statistically significant, with women having higher ordered log odds of reporting negative affect than men (p < .001). As expected, negative affect at baseline (Wave 2) predicted negative affect at Wave 5 (p < .001).

Table 4.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results for Negative Affect Outcome

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors | ||||

| Altruistic attitudes W2 | −0.143 | 0.186 | −0.234 | 0.198 |

| Hours of volunteering W2 | −0.024 | 0.020 | −0.018 | 0.021 |

| Informal helping W2 | 0.077 | 0.132 | 0.049 | 0.148 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | 0.982*** | 0.206 | ||

| Age W2 | −0.006 | 0.021 | ||

| Marital status W2 | 0.343 | 0.184 | ||

| Negative affect W2 | 1.126*** | 0.119 | ||

| Health-related resources | ||||

| Driving status W2 | 0.108 | 0.236 | ||

| Functional limitation W2 | 0.503* | 0.223 | ||

| Chronic illness W2 | 0.101 | 0.067 | ||

| Mortality λ | 0.097 | 0.346 | −0.169 | .375 |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 1244.71(4) | 1096.79(11) | ||

Note. b = slope estimate; SE = standard error; df = degree of freedom; W2 = Wave 2; W5 = Wave 5; effective n = 585.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Depressive Symptoms

In Model 1, we entered altruistic attitudes and pro-social behaviors. Frequency of volunteering (p = .005) and providing informal help to others (p = .028) emerged as significant predictors of Wave 5 depressive symptomatology (see Table 5). This evidence suggests that the ordered log odds of experiencing depressive symptoms at Wave 5 are lower for respondents with higher frequency of volunteering and informal helping. In Model 2, we controlled for demographic characteristics, driving, and health status. While frequency of volunteering remained significant (p = .003), informal helping was no longer a significant predictor. In terms of the control variables, gender (p < .001), functional limitations (p < .001), and baseline depressive symptoms (p < .001) were found to be significant predictors of depressive symptoms at Wave 5. Thus, lower levels of volunteering, being female, having greater functional limitations and higher levels of baseline depression predict higher levels of depressive symptoms at Wave 5.

Discussion

Altruistic attitudes were both prevalent and salient in this community sample of older adults. Almost one half of the sample also engaged in formal volunteer activities, affirming the high value placed on civic engagement by this group (Musick & Wilson, 2008). Informal helping of friends and neighbors was also prevalent among respondents, indicating their prososcial connection with others. These findings attest to the value placed on contributory roles by this group of elders. Our results confirm the shift that has been noted in gerontological theorizing from dependency, autonomy, and exchange-based views of aging, to recognition of the salience of contributory roles to older adults (Kahana, Midlarsky et al., 1987; Morrow-Howell, 2010). Residence in a retirement community meant that respondents’ helping behaviors primarily benefited other elders, contributing to social capital of elders in this milieu (Theurer & Wister, 2010). Among older adults living closer to their families, helping of younger family members may provide critical benefits to helper’s well-being (e.g., Hayslip & Kaminsky, 2005; Kropf & Yoon, 2006).

Our study makes a contribution to the literature by considering both positive and negative mental health indicators as potential outcomes of altruistic attitudes and of helping behaviors. Supporting expectations raised by the positive psychology literature (Seligman, 2002), both altruistic attitudes and helping behaviors proved to be significant predictors of positive affect in multivariate models. These models indicate a more limited influence of altruism and prosocial behaviors on negative indicators of mental health such as depressive symptoms and negative affect.

Prior social psychological theoretical frameworks concerned with understanding positive indicators of psychological well-being offer some intriguing suggestions about the processes that may link prosocial orientations and positive well-being outcomes. Diener’s definition of happiness in his landmark 1984 article in Psychological Bulletin refers to leading a virtuous life as a requisite of happiness. Such a life calls for prosocial attitudes and behaviors. The connection between positive affect and altruistic orientations is a central theme within positive psychology. Formulations that focus on positive, rather than negative affectivity, typically invoke other directed orientations, such as expressing gratitude and concern for others (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Experimental studies observed increased positive affect after committing acts of kindness (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Positive affect is also embedded in the dynamics of human flourishing. Flourishing is defined as living “with an optimal range of human functioning, one that connotes goodness, generativity, growth and resilience” (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005, p. 678).

These expectations are consistent with findings of our study in linking prosocial orientations and positive affect in late life. The present study thus makes a contribution to integrating gerontological understandings about the values of volunteering for psychological well-being with social psychological understandings linking positive affectivity and prosocial orientations. The absence of linkages between negative affect and prosocial orientations may be due to more individual rather than networked aspects of depressive symptoms and negative affect. Experiences and expressions of negative emotions are likely to share more with individual circumstances than with aspects of volitional connectedness to others. Specifically negative emotions have been found to be associated with negative life events and circumstances rather than with positive engagement (Reich, Zautra, & Davis, 2003). Our findings thus contribute to a growing body of work documenting how negative and positive emotionality cooccur and can operate conjointly.

Our results are in accord with prior longitudinal studies that link volunteering and well-being in late life (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). In our study this relationship was tested in the context of low to moderate levels of volunteering. We recognize that prior research has called attention to potential adverse effects of very high levels of volunteering (Windsor et al., 2008). In our research volunteering was the most consistent predictor of the well-being outcomes that we studied. Our study also underscores the salience of both altruistic attitudes and behavioral manifestations of altruism for the maintenance of positive affect that contributes to mental health in late life.

The observed relationship of altruistic attitudes and prosocial behaviors to well-being outcomes deserves special attention. Altruistic attitudes and predispositions reflect a generosity of spirit, which is independent of the older adult’s ability to offer concrete help to others. Our results confirm that altruistic attitudes have an independent influence on positive emotions in late life. Chronic illness and functional limitations are likely to reduce formal volunteer activities among the very old and diminish their ability to provide instrumental assistance to others (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). However, the attitudinal component that motivates such behaviors is maintained, even in very old age (Midlarsky & Kahana, 2007). Such attitudes are likely to reflect compassion for others and other oriented concerns (Post, 2005). Altruistic attitudes can thus enhance positive emotions in late life.

The significant influence of civic engagement in the form of volunteering on the maintenance of positive affective states and the diminishing of depressive symptomatology is consistent with prior literature about the value of formal participation among the elderly (Musick & Wilson, 2008). We thus acknowledge the important role of prosocial behavior for well-being in late life.

In regard to demographic characteristics, we found support for previously established linkages between female gender and increased incidence of negative affect and depressive symptomatology (Blazer, 2005). It is noteworthy that gender was not related to positive affect. These results are consistent with expectations that positive and negative affective states have distinct and different predictors (Robinson-Whelen, Kim, MacCallum, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1997).

Associations between age and the outcome variables also reveal separate patterns for positive and negative affective states. However, the relationships here are a bit more complex. Although we found no significant association between age and indicators of negative affect, diminished positive affect was associated with older age. This finding is in accord with prior observations of the blunting of positive affect in old age (Diener et al., 1985).

The three health/mobility-related control variables utilized in our study included driving status, functional limitations and chronic illness. We expected limitations in these functions to have a negative influence on our outcome variables. Our findings confirmed these expectations primarily with regard to functional limitations. Chronic illness was predictive only of life satisfaction outcomes. Driving status had no significant impact on any of the outcome variables considered. In this sample, the relatively rare inability to drive apparently limited respondents’ capabilities as volunteers without directly influencing positive or negative affective states.

Among limitations of our research, we note the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in our sample that diminishes generalizability of the findings. Lack of diversity was a function of very limited presence of ethnic minorities in Sunbelt retirement communities. Residence in retirement communities is also likely to reflect selection factors that attract older adults to migrate to the Sunbelt and live in age segregated and leisure oriented communities (Walters, 2002). Thus, our findings are not generalizable to older adults residing in different community contexts. Future studies can also further elucidate the linkages we established by exploring mechanisms that may link prosocial orientations to well-being outcomes. Having multiple data points in longitudinal research will facilitate such research. In terms of methodological limitations we acknowledge that altruism, the key dispositional indicator used in our study was based on a newly developed scale that requires further validation in future research.

In reflecting upon the relationship between positive affect and helping behavior, psychologists have posited alternative causal linkages (Aspinwall, 1998). Thus, researchers have argued that positive mood tones or emotions enhance helping behavior and cooperation (Hertel, Neuhof, Theuer, & Kerr, 2000; Isen, Clark, & Schwartz, 1976). We recognize that emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral linkages are complex and often reciprocal. Indeed, there is evidence from prior longitudinal research for both the selection and compensation hypotheses regarding mood being antecedent to volunteering (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001; Li & Ferraro, 2005). The longitudinal design of our study provides support for the causal ordering proposed here, indicating that prosocial behaviors and altruistic attitudes contribute to subsequent positive emotions.

Our findings also offer useful lessons about late life potential for the maintenance of psychological well-being. There is compelling support for the contribution of altruistic orientations and helping behaviors to mental wellness in later life, confirming tenets of strength-based approaches to gerontology (Ronch, 2003). Such orientations suggest that expressions of empathy for others contribute to a collective and enduring identity (Mroczek & Little, 2006; Sorokin, 2002). Older persons have a limited temporal horizon for personal attainments and individual gratification. The ability to help others and to derive satisfaction from such actions transcends a personal future and allows for maintenance of meaning in life that fosters psychological well-being (Post, 2005). Such meaningfulness is also consistent with Erikson’s concepts of generativity and of ego integrity in late adulthood (Erikson, 1968).

The present study focused on elucidating linkages between a broad array of prosocial orientations and diverse aspects of positive as well as negative emotionality. Future research can refine the understandings we gained by specifying conditions that enhance these linkages. Thus, for example, the role of personal and social resources in moderating the relationships between altruistic behaviors and orientations represents a promising area for inquiry. A useful model for such studies is offered by indications in prior research about the role of religiosity in contributing to prosocial orientations on the one hand (Lam, 2002) and in moderating linkages between altruism and psychosocial well-being on the other (Krause, 2009).

This research offers support for a broader conceptualization of prosocial orientations than the traditional focus on volunteering in the gerontological literature. We demonstrate that diverse prosocial orientations and behaviors can promote mental health in late life. Enduring emphasis by older adults on the welfare of significant others has been demonstrated even as older adults reflect on the approaching end of life (Kahana, E., Kahana, B., Lovegreen et al., 2011). Such persistent desire by older persons for social connectedness suggests the value of policies and practices that affirm the enduring benefit of altruism and helping, in old age.

The implications of informal and formal helping roles by older adults for social policy are far reaching. They help redefine perceptions of old age from one of dependency and hence a liability to society, to elders being resources in their communities (Liu & Besser, 2009). This is consistent with conceptualizations of contributory and proactive orientations to aging (Kahana & Kahana, 2003). With recognition of population aging the contributory roles of elders as mentors, volunteers, and productive citizens can lead to a paradigm change in perceptions and social narratives about old age. Our research indicates that prosocial attitudes and behaviors represent a salient dimension for understanding and promoting successful aging.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Grant R01-AGO7823 from The National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Inter-science; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A, Sagy S. Confronting developmental tasks in the retirement transition. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:362–368. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG. Rethinking the role of positive affect in self-regulation. Motivation and Emotion. 1998;22(1):1–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1023080224401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barrett JE, editors. Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 315–350. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. The age of melancholy: “Major depression” and its social origin. 1. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM. Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science. 2003;14:320–327. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:136–151. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi LH. Factors affecting volunteerism among older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2003;22:179–196. doi: 10.1177/0733464803022002001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Adams K, Kahana E. The impact of transportation support on driving cessation among community-dwelling older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2012;67:392–400. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B. Independence through social networks: Bridging potential among older women and men. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66B:782–794. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78(1):98–104. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64(1):21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist. 2006;61:305–314. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S. The non-obvious social psychology of happiness. Psychological Inquiry. 2005;16(4):162–167. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1604_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Piliavin JA, Schroeder DA, Penner LA. The social psychology of prosocial behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Generativity and ego integrity. In: Neugarten BL, editor. Middle age and aging. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1968. pp. 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH, Erikson J, Kivnick H. Vital involvement in old age. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio EM. Sense of mattering in late life. In: Ameshensel C, Schieman S, Wheaton B, editors. Advances in conceptualization of the stress process. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pillemer KA, Silverstein M, Suitor JJ. The baby boomers’ intergenerational relationships. The Gerontologist. 2012;52:199–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:901–908. doi: 10.1002/pon.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham heart study. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B, Losada M. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist. 2005;60:678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Still happy after all these years: Research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. Journals of Gerontology. 2010;65:331–339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Fillenbaum GG. OARS methodology. A decade of experience in geriatric assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1985;33:607–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb06317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibran K. The prophet. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf V. Envy. Fort Bragg, CA: Cypress House; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Kaminsky P. Grandparents raising their grandchildren. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:262–269. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;47:153. doi: 10.2307/1912352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel G, Neuhof J, Theuer T, Kerr NL. Mood effects on cooperation in small groups: Does positive mood simply lead to more cooperation? Cognition & Emotion. 2000;14:441–472. doi: 10.1080/026999300402754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isen A, Clark M, Schwartz M. Duration of the effect of good mood on helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1976;34:385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Patient proactivity enhancing doctor–patient–family communication in cancer prevention and care among the aged. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B, Kercher K. Emerging lifestyles and proactive options for successful aging. Ageing International. 2003;28:155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B, Lovegreen L, Kahana J, Brown J, Kulle D. Research in the Sociology of Health Care. Vol. 29. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing; 2011. Health-care consumerism and access to health care: Educating elders to improve both preventive and end-of-life care; pp. 173–193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kelley-Moore J, Kahana B. Proactive aging: A longitudinal study of stress, resources, agency, and well-being in late life. Aging and Mental Health. 2012;16(4):438–451. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.644519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Lawrence RH, Kahana B, Kercher K, Wisniewski A, Stoller E, Stange K. Long-term impact of preventive proactivity on quality of life of the old-old. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:382–394. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Midlarsky E, Kahana B. Beyond dependency, autonomy, and exchange: Prosocial behavior in late-life adaptation. Social Justice Research. 1987;1:439–459. doi: 10.1007/BF01048387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore J, Schumacher J, Kahana E, Kahana B. When do older adults become “disabled”? Acquiring a disability identity in the process of health decline. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2006;47:126–141. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based volunteering, providing informal support at church, and self-rated health in late life. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21(1):63–84. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf NP, Yoon EK. Grandparents raising grandchildren. In: Berkman B, editor. Handbook of social work in health and aging. New York, NY: Oxford; 2006. pp. 355–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lam P. As the flocks gather: How religion affects voluntary association participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Moss MS, Winter L, Hoffman C. Motivation in later life: Personal projects and well-being. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:539–547. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ferraro KF. Volunteering and depression in later life: Social benefit or selection processes? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(1):68–84. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AQ, Besser T. Social capital and participation in community improvement activities by elderly residents in small towns and rural communities. Rural Sociology. 2003;68:343–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00141.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Three fragments from a sociologist’s notebook: Establishing the phenomenon, specified ignorance, and strategic research materials. Annual Review of Sociology. 1987;13:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.13.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Midlarsky E, Kahana E. Altruism in later life. Vol. 196. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Midlarsky E, Kahana E. Altruism, well-being, and mental health in late life. In: Post SG, editor. Altruism and health: Perspectives from empirical research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Midlarsky E, Midlarsky M. Echoes of genocide. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 2004;28(2):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N. Volunteering in later life: Research frontiers. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65B:461–469. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N, Hinterlong J, Rozario PA, Tang F. Effects of volunteering on the well-being of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Little TD, editors. Handbook of personality development. 1. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Wilson J. Volunteers: A social profile. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin JA. Altruism and helping: The evolution of a field: The 2008 Cooley-Mead presentation. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2009;72:209–225. doi: 10.1177/019027250907200305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Post S. Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12(2):66–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Davis MC. Dimensions of affect relationships: Models and their integrative implications. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7:66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Riche Y, Mackay W. PeerCare: Supporting awareness of rhythms and routines for better aging in place. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 2010;19(1):73–104. doi: 10.1007/s10606-009-9105-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Whelen S, Kim C, MacCallum RC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Distinguishing optimism from pessimism in older adults. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1345–1353. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronch JL. Mental wellness in aging: Strengths-based approaches. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP, Chrisjohn RD, Fekken GC. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1981;2:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(81)90084-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J. Chronic illness and depressive symptoms in late life. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.020. doi.org/10/1016j.socscimed.2004.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman PM. Time for my life now: Early boomer women’s anticipation of volunteering in retirement. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(2):245–254. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. The handbook of positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen T, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60:410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need-satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:482–497. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualising best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1(2):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. Is it possible to become happier? (And if so, how?) Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;1(1):129–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin PA. The ways and power of love: Types, factors, and techniques of moral transformation. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Theurer K, Wister A. Altruistic behaviour and social capital as predictors of well-being among older Canadians. Ageing and Society. 2009;30:157–181. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tornstam L. Stereotypes of old people persist: A Swedish “Facts on aging quiz” in a 23-year comparative perspective. International Journal of Aging and Later Life. 2007;2:33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA, Hewitt LN. Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(2):115–131. doi: 10.2307/3090173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters W. Place characteristics and later-life migration. Research on Aging. 2002;24:243–277. doi: 10.1177/0164027502242004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton J, Terry DJ, Rosenman LS, Shapiro M. Differences between older volunteers and nonvolunteers: Attitudinal, normative, and control beliefs. Research on Aging. 2001;23:586–605. doi: 10.1177/0164027501235004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N, Ryan RM. When helping helps: An examination of motivational constructs underlying prosocial behavior and their influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:222–224. doi: 10.1037/a0016984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:215–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor T, Anstey K, Rodgers B. Volunteering and psychological well-being among young old adults: How much is too much? The Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):59–70. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Kahana B, Kahana E, Hu B, Pozuelo L. Joint modeling of longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and mortality in a sample of community-dwelling elderly people. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:704–714. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ac9bce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]