Abstract

Background

Mature acetylcholine receptor (AChR) isoform normally mediates muscle contraction. The hypothesis that α7AChRs upregulate during immobilization and contribute to neurotransmission was tested pharmacologically using specific blockers to mature (waglerin-1), immature (αA-OIVA), and α7AChRs methyllycaconitine, and non-specific muscle AChR antagonist, α-bungarotoxin.

Methods

Mice were immobilized; contralateral limb was control. Fourteen days later, anesthetized mice were mechanically ventilated. Nerve-stimulated tibialis muscle contractions on both sides were recorded, and blockers enumerated above sequentially administered via jugular vein. Data are mean ± S.E.

Results

Immobilization (N=7) induced tibialis muscle atrophy (40.6 ± 2.8 vs 52.1 ± 2.0 mg, p<0.01) and decrease of twitch tension (34.8 ± 1.1 vs. 42.9 ± 1.5 g, p< 0.01). Waglerin-1 (0.3 ± 0.05 μg/g) significantly (p=0.001, N=9) depressed twitch tension on contralateral (≥ 97%) versus immobilized side (~45%). Additional waglerin-1 (total dose 1.06 ± 0.12 μg/g or ~15.0 X ED50 in normals) could not depress twitch ≥ 80% on immobilized side. Immature AChR blocker, αA-OIVA (17.0 ± 0.25 μg/g) did not change tension bilaterally. Administration of α-bungarotoxin (N=4) or methyllycaconitine (N=3) caused ≥ 96% suppression of the remaining twitch tension on immobilized side. Methyllycaconitine, administered first (N=3), caused equipotent inhibition by waglerin-1 on both sides. Protein expression of α7AChRs was significantly (N=3, p<0.01) increased on the immobilized side.

Conclusions

Ineffectiveness of waglerin-1 suggests the twitch tension during immobilization is maintained by receptors other than mature AChRs. Since αA-OIVA caused no changes, immature AChRs contribute minimally to neurotransmission. During immobilization ~20% of twitch tension is maintained by upregulation of α-bungarotoxin- and methyllycaconitine-sensitive α7AChRs.

INTRODUCTION

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) on the skeletal muscle membrane are pivotal for neurotransmission and muscle contraction.1–2 Typically, two types of muscle AChRs, the immature or fetal AChRs containing 2α1β1δγ subunits, and the mature AChRs consisting of 2α1β1δε subunits have been described.1–5 In the normal innervated muscle, the mature AChRs are present only in the junctional area, and are involved in neurotransmission. When there is deprivation of neural influence or activity (e.g., fetus or denervation), the γ subunit containing immatureAChRs are upregulated and expressed throughout the muscle membrane.1–5 Neuronal nicotinic AChRs containing five homomeric α7-subunits, previously described only in the central nervous system, have more recently been described in skeletal muscle following denervation only.6,7

In some pathologic states, despite the presence of innervation, upregulation of the immature AChRs occurs.3–5 For example, several studies in the past three decades using varied models of immobilization have shown that disuse of muscle leads to muscle atrophy, and de novo expression of immature AChRs throughout the muscle membrane, despite the presence of continued innervation.3–5,8–11 The upregulation of immature AChRs during immobilization has been documented using electrophysiology, ligand binding, in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction techniques.2,8–12 This upregulation of immature AChRs with immobilization occurs mostly in the extra-junctional area,8,11,12 although the junctional area expression has been documented by in situ hybridization.12 The contribution of immature AChRs to neurotransmission during immobilization is unknown. It has been assumed, however, that the expression of the immature AChRs in the junctional area contributes to the resistance to non-depolarizing muscle relaxants during immobilization.3–5,9–11 Although the immobilized muscle behaves like denervated muscle in some aspects (e.g., muscle wasting and upregulation of immature AChRs), whether α7AChR expression also occurs following immobilization, as in denervation, has never been tested.

Cobra snake (Bungarus multicinctus) venom, α-bungarotoxin (αBTX), can bind irreversibly to all muscle AChRs including α7AChRs to block acetylcholine-induced currents or neurotransmission.1,2 Thus αBTX, like clinically used muscle relaxants (pancuronium, atracurium), has no specificity for the three AChR isoforms expressed in muscle.1,2,8 A snake toxin from the viper, Trimeresurus wagleri, called waglerin-1, has been described and binds with high-affinity and high-selectivity only to mature AChRs in vitro in oocytes and in vivo in mice.13–15 More recently, another toxin from marine cone snails, Conus obscurus and pergrandis, termed αA-OIVA has been characterized and inhibits only the fetal (immature) AChRs with high affinity and unprecedented specificity both in vitro in oocytes and ex vivo in rodents.14,16–18 Methyllycaconitine is a specific α7AChR antagonist derived from Delphinium (Larkspur) plant. Its specificity for the α7AChRs has been described both in vivo and in vitro.19–21

In this study using mechanomyographic techniques together with Waglerin-1, αA-OIVA, and methyllycaconitine, as specific antagonist ligands to the mature, immature, and α7AChRs, respectively, and with αBTX, we tested the hypothesis that α7AChRs are upregulated in muscle following immobilization and contribute to neurotransmission, while the upregulated immature AChRs contribute minimally to neurotransmission. In addition to in vivo pharmacological methods, the presence of α7AChR protein on the muscle membrane following disuse was also confirmed biochemically by the use of immunoblot (western blot).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Animals

The study was approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Adult male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Labs, ME), weighing 25–30 g, were used for the study. The mice were housed under a 12-hr light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum and allowed to accommodate to the standard conditions of our facility for at least a week.

2. Surgical Procedures

The pining-immobilization model, previously described and used in many studies, was used for the current studies.8–11 After one week of acclimatization, immobilization procedure was performed. The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60–70 mg/kg intraperitoneal). The knee and ankle joints were immobilized by insertion of a 25-G hypodermic needle through the proximal tibia into the distal femur to produce 90° flexion at the knee, and a 27-G needle through the calcaneus into the distal tibia to fix the ankle joint at 90°. The sham-immobilized limb was subjected to the same manipulations, including boring a hole through the joints, but the pins were not maintained to immobilize the joint. Based on our previous reports, sham-immobilization of the contralateral leg does not alter muscle function, morphology, AChR number, or muscle weight compared to unimmobilized limbs of naïve rodents.10,11 A more recent study by us in mice again confirmed that the contralateral side does not differ from unimmobilized naïve animals.22 In the present study, therefore, the contralateral sham-immobilized hind limb served as the control. After recovery from anesthesia, the animals were returned to their cages.

3. Neuromuscular Function Studies

To characterize the role of each AChR isoform to neurotransmission, nerve-evoked tibialis muscle tension responses were recorded at 14 days after immobilization. The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60–70 mg/kg intraperitoneal), and tracheostomy was performed for mechanical ventilation with air at 140–150 breaths/minute with a tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg (MiniVent Type 845, Hugo Saches Electronik-Harvard Apparatus Gmbh, March-Hugstetten, Germany). The jugular vein was cannulated for fluid and drug administration. Adequate depth of anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of the withdrawal response to toe clamping. Anesthesia was maintained with supplemental intermittent doses of pentobarbital 10–20 mg/kg intraperitoneal, empirically administered every 15–20 minutes. The body temperature was monitored using a rectal thermistor and maintained at 35.5–37°C with a heat lamp.

Neuromuscular transmission was monitored by evoked mechanomyography using a peripheral nerve stimulator (NS252, Fisher & Paykel Health Care, Irvine, CA) along with a Grass Force transducer and software (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). With the mice in dorsal recumbency, the tendon of insertion of the tibialis muscle was surgically exposed on each side and individually attached to separate grass FT03 force displacement transducers. The sciatic nerve was exposed at its exit from the lumbosacral plexus at the thigh and tied with ligatures for indirect nerve stimulation of the muscles. Distal to the ligatures, stimulation electrodes were attached for nerve-mediated stimulation of the tibialis muscle. The knee was rigidly stabilized with a clamp to prevent limb movement during nerve stimulation. Baseline tensions of 10 grams, which yielded optimal evoked tensions, were applied on the immobilized and sham-immobilized tibialis muscles. The sciatic-nerve-evoked tensions of the respective tibialis muscles that were calibrated in grams of force were recorded via a Grass P122 amplifier and displayed using the Grass Polyview Software (Grass Instruments). Supramaximal electrical stimuli of 0.2 msec duration were applied to the sciatic nerve at 2 Hz for 2 sec (train-of-four pattern) every 30 sec using a Grass S88 stimulator and SIU5 stimulus isolation units (Grass Instruments). In view of the fact that the main focus of the experiments were to characterize the expression of the immature and α7AChRs and their function in neurotransmission, detailed evaluation of the muscle function (e.g., tetanic contraction and fade) was not performed. Furthermore, repetitive tetanic stimulation during the cumulative administration of the AChR antagonists will result in fatigue of muscle.

4. Study of the role of mature AChRs in neurotransmission

The sciatic nerve-tibialis muscle preparation in vivo was stabilized for at least 30 minutes, prior to the administration of specific AChR antagonists. In the initial set of experiments, waglerin-1, the specific ligand for mature AChRs,13–15 synthesized by the Peptide Core Facility, at Massachusetts General Hospital, was administered intravenously and the twitch responses noted for each cumulative dose. L.D.50 of waglerin-1 in mice is ~0.33 mg/kg intraperitoneally (95% C.I. 0.30–0.36).23 An initial bolus dose of 5 μg of waglerin-1 was administered intravenously followed by increments of 2 μg until the first twitch (T1) in the train-of-four stimulations decreased to ≥75% of baseline on both sides. Each incremental dose of waglerin-1 (2 μg) was given only when the previous dose had produced maximal effect, indicated by three equal consecutive T1 twitches in both muscles or an increasing T1 response in either muscle. The interval between doses was 3–4 minutes. In view of the poor response to waglerin-1 on the immobilized side, additional doses were given until twitch height did not change with repetitive doses.

5. Study of the role of immature AChRs in neurotransmission

The second phase of our experiment was the study of the role of immature AChRs in neurotransmission during immobilization. The α-conotoxin, αA-OIVA, highly selective blocker of the immature AChR (synthesized by Peptide Core Facility, Massachusetts General Hospital), was used. Previous studies have tested its potency to block immature AChRs in oocytes and its efficacy to block acetylcholine-induced currents in the immature AChR in the rat ex vivo.14,16–18 The L.D.50 of αA-OIVA in vivo is unknown since immature AChRs are not normally expressed. This ligand blocks mouse fetal muscle AChRs expressed in oocytes (IC50 of 0.51 nM or 0.94 ng/ml) with 600-fold greater affinity than for the adult mature muscle AChRs.14,16,17 The IC50 for ex vivo blocking of fetal receptors expressed in denervated muscle of rodents is 1μM.18

When the twitch responses did not change with continued administration of waglerin-1 in the studies described above, cumulative doses of αA-OIVA were administered intravenously every 3–4 minutes while observing twitch responses, alternating with waglerin-1, if twitch tension was recovering. When the twitch tension did not change with αA-OIVA, αBTX (which blocks mature, immature and α7AChRs) was administered (0.165 μg/g, each time) intravenously every 3–5 minutes until ≥ 97% twitch depression.

6. Study of the role of α7AChRs in neurotransmission

The nerve-muscle preparation was the same as described previously. In a new group of mice, after stabilization of twitch, waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA were administered until twitch responses were unchanged following these toxins. At this time methyllycaconitine, derived from delphinium-larkspurs alkaloid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), a specific antagonist of α7AChRs,19–21 was administered in incremental doses.

We then posited that if α7AChRs are the cause of the resistance to block by waglerin-1, if one preemptively blocks the α7AChRs, then the response to waglerin-1 should be equal on the immobilized and contralateral side. Therefore, in a separate set of animals, after stabilization of the nerve-evoked muscle tension responses, methyllycaconitine (50 μg) was administered as a bolus to block the α7AChRs in muscle on both sides. After a period of 10 minutes, αA-OIVA was administered, as performed previously, and changes in twitch tension noted. When twitch tension was unchanged, waglerin-1 was then administered.

7. Immunoblot for protein expression of α7AChRs on muscle membrane

Following the termination of the functional studies on methyllycaconitine, the tibialis muscle was harvested and stored at −80°C. At a later time, the muscle samples were thawed, powdered in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized in homogenization buffer (Sigma) containing protease inhibitor (Roche, San Francisco, CA) as described previously.24 The samples were centrifuged, and aliquots of the supernatant containing equal amounts of protein (by Bradford Assay) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously.25 Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) per lane were subjected to NuPAGE and then blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The membrane was blocked by 5% nonfat dry milk. Anti-α7AChR (dilution 1:1,000), anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:20,000) (Abcam, Cambridge MA) were used as primary antibodies. The membranes were incubated in horseradish perioxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 minutes (dilution 1:5,000). The specific proteins were detected by exposing the membrane to Kodak X-Omat films (Hyglo Quick Spray., Denville Scientific, Inc., Methuchen, NJ).

8. Statistical Analyses

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. All doses were converted to μg/g body weight. The differences of baseline twitch heights, weights of tibialis muscles, and specific twitch tensions between immobilized and contralateral side were analyzed by paired-sample t-test (two-tailed, not equal-variance assumption). The changes in percent twitch depression of first twitch tension (T1) relative to base-line after administration of the study drugs (waglerin-1, αA-OIVA, αBTX and methyllycaconitine), and the cumulative doses of the study drugs at each measure point between the two sides were compared using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparative tests with Bonferroni correction. To determine effective dose of Waglerin-1 for 50% and 95% twitch depression (ED50, ED95) on each side, the percent twitch depression of the first twitch of train-of-four (T1) relative to baseline was transformed to logit scale and plotted against the logarithm of the cumulative dose, and then linear regression analyses performed. Comparison between ED50 and ED95 values for each side were made using unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test with Welch’s corrections. Values were assumed to be significant if the p-value was < 0.05. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

1. Stability and consistency of model

Our initial set of experiments were to characterize the muscle mass loss, and loss of tension associated with immobilization (disuse) in this model described recently.22 Since the focus of mechanomyographic experiments were on the tibialis only tibialis muscle weights are reported. The weight of the mice used for these experiments were 28.8 ± 1.0 g (N = 7). Tibialis muscle mass was significantly decreased on the immobilized compared to contralateral side (40.6 ± 2.8 vs. 50.1 ± 2.0 mg, p<0.01; Table 1). The significant difference between the two sides was also observed when muscle weights on both sides were normalized to body weight (1.4 ± 0.1 vs. 1.8 ± 0.1 mg/g, p<0.01, respectively). Consistent with loss of muscle mass, the tension generation by the immobilized muscle was decreased compared to the contralateral side (34.8 ± 1.5 vs 42.9 ± 2.0 g, p<0.01). The specific tensions, tensions normalized to muscle weight and body weight, however, did not differ between the two sides (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tibialis Muscle Mass and Tensions at 14 Days of Immobilization

| Muscle Mass (mg) | Muscle Mass/B.W.* (mg/g) | Twitch Tension (g) | Specific Tension** (g/mg) | Specific Tension/B.W.¶ (g/mg/B.W.) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contra | Immob | Contra | Immob | Contra | Immob | Contra | Immob | Contra | Immob | |

| Mean | 52.1 | 40.6 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 42.9 | 34.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 23.7 | 24.8 |

| S.E. | 2.0 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| P Value ≤ | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.43 | |||||

Contra And Immob are Contralateral and Immobilized sides of the same animals.

Muscle Mass/B.W. is the muscle mass normalized to body weight.

Specific Tension is tension per gram muscle weight.

Specific Tension/B.W. is the tension per gram muscle weight normalized to body weight.

2. Role of mature AChRs in neurotransmission during immobilization

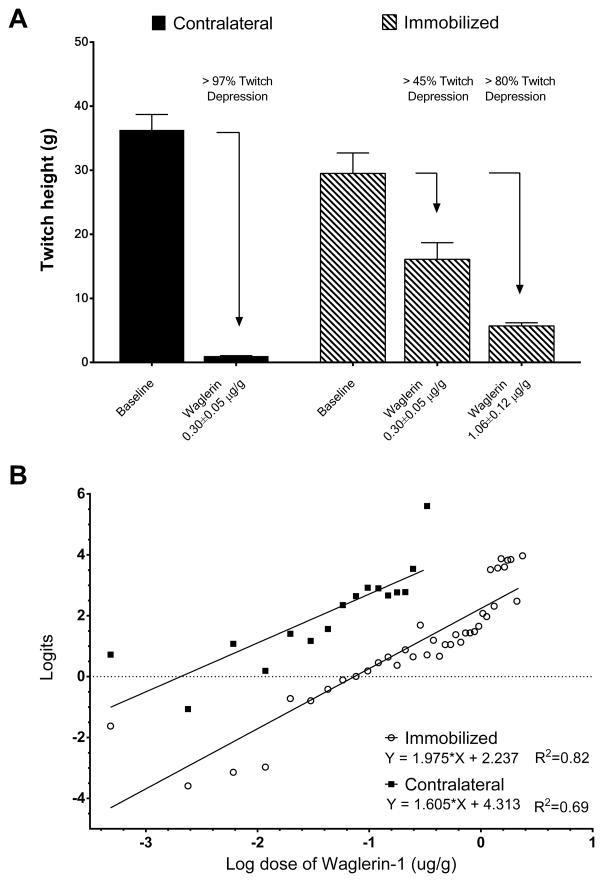

For the study of the role mature/immature AChRs with the use of Waglerin-1, αA-OIVA and BTX a new set of animals were immobilized. The number of animals immobilized were 17, but only 9 were used for the studies. The animals were excluded due to death from bleeding during experiment (n=1), decanulation of vein catheter (n=1), inability set twitch tensions on one or other side (n=2), and loosening of immobilization pin (unstable immobilization) when examined daily (n=4). The mean body weight of the animals was 27.5 ± 1.0 g. The twitch tension developed by tibialis during nerve-evoked muscle contraction on the contralateral (unimmobilized) side was 36.3 ± 2.4 g, which was significantly higher (P = 0.014) than 29.5 ± 3.2 g of the immobilized side. Mature AChR antagonist, waglerin-1 (0.30 ± 0.05 μg/g) caused significantly ≥ 97% twitch suppression on contralateral side compared to the immobilized side (P = 0.001), where the tension depression was ~45% only (Figure 1A). The twitch tension on immobilized side could not be depressed ≥ 80% with additional doses (0.76 ± 0.11 μg/g) of waglerin-1 (or total dose of 1.06 ± 0.12 μg/g). The total dose of waglerin-1 administered was ~15 X ED50 of the contralateral (normal) side (0.07 ± 0.06 ug/g), and yet could not inhibit twitch ≥ 80% on the immobilized side. The ED doses of waglerin-1calculated from linear regression were 0.32 ± 0.22 μg/g vs. 0.07 ± 0.06 μg/g (ED50) and 1.43 ± 0.76 vs. 0.41 ±0.04 μg/g (ED95), respectively. The ED95 of Waglerin-1 was significantly (p=0.0002) higher on the immobilized side (Fig 1B) compared to contralateral side.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Immobilization leads to decreased contribution by mature acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) to neurotransmission

The baseline twitch tension on the contralateral (unimmobilized) side was 36.3 ± 2.4 g, and that on the immobilized side was 29.5 ± 3.2 g, which was significantly (P = 0.014, N = 9) lower, confirming the effectiveness of immobilization. Waglerin-1 (0.30 ± 0.05 μg/g) depressed the twitch response on contralateral side to greater than ≥ 97%, while the twitch depression on immobilized side was 45% (P = 0.001). Additional dose of Waglerin-1 (0.76 ± 0.11 μg/g) or a total dose of 1.06 ± 0.12 μg/g could not cause twitch suppression ≥ 80%. This suggests that AChRs other than mature AChRs contribute to neurotransmission.

Figure 1B. Dose-response curve for Waglerin-1 is shifted to the right on the immobilized versus contralateral side

The cumulative log doses of waglerin-1 were plotted against percent twitch inhibition (logit plot). The doses of waglerin-1 that produced 50% depression of the first twitch of the train-of-four (T1) Effective Dose (ED50) on immobilized and contralateral side were 0.32 ± 0.14 μg/g and 0.07 ± 0.06 μg/g, respectively. The ED95 of waglerin-1 was significantly (p=0.0002) higher on the immobilized side (1.43 ± 0.16 μg/g vs. contralateral side (0.41 ± 0.04 μg/g) indicating resistance to the effects of waglerin-1 on the immobilized compared to the unimmobilized side.

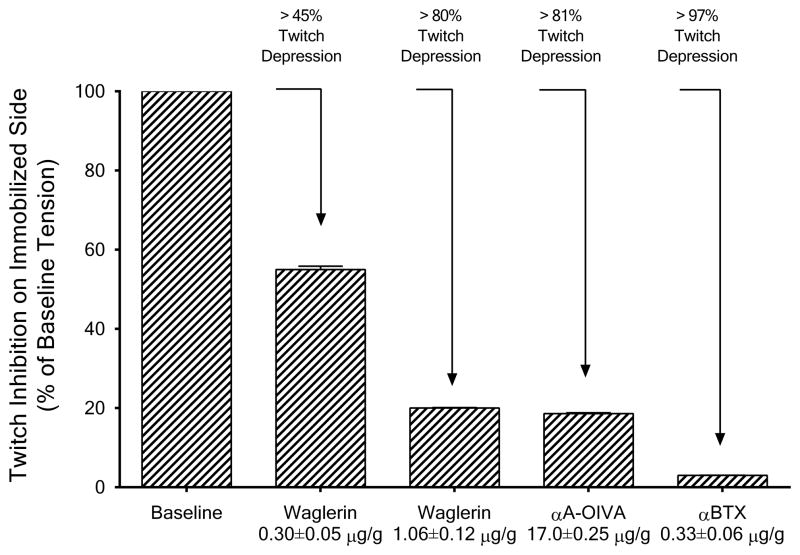

3. Role of immature AChRs on neurotransmission

Previously we and others have reported that disuse by immobilization was associated de novo expression of transcripts of the immature AChRs on the muscle membrane, despite the nerve being intact.8,9,10–12 In this component of the study, the contribution of immature AChRs to neurotransmission was assessed. In the same animals that received waglerin-1, the administration of αA-OIVA in a total dose of (17.0 ± 0.25 μg/g), caused minimal changes in twitch tension on the immobilized (Figure 2) and contralateral sides. Since there was 99% twitch suppression on the contralateral side, the data for that side is not shown. Shortly thereafter, since an approximate 20% of twitch height was still present, αBTX was administered (total 0.33 ± 0.06 μg/g), and caused ≥ 97% depression of twitch on the immobilized side (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Immature muscle acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) do not contribute to neurotransmission.

At the end of the waglerin-1 study, the conotoxin, αA-OIVA totaling 17.0 ± 0.25 μg/g was administered and caused minimal changes (≤ 1%) in twitch tension on the immobilized side. On the contralateral side the 99% twitch inhibition after waglerin-1 did not change after αA-OIVA (Data not shown). The subsequent administration of α-bungarotoxin (αBTX) (0.33 ± 0.06 μg/g) caused ≥ 97% twitch depression on the immobilized side, indicating that an approximate 20% of the twitch height is maintained by αBTX-sensitive nicotinic AChRs. Data are presented as percent of immobilized side.

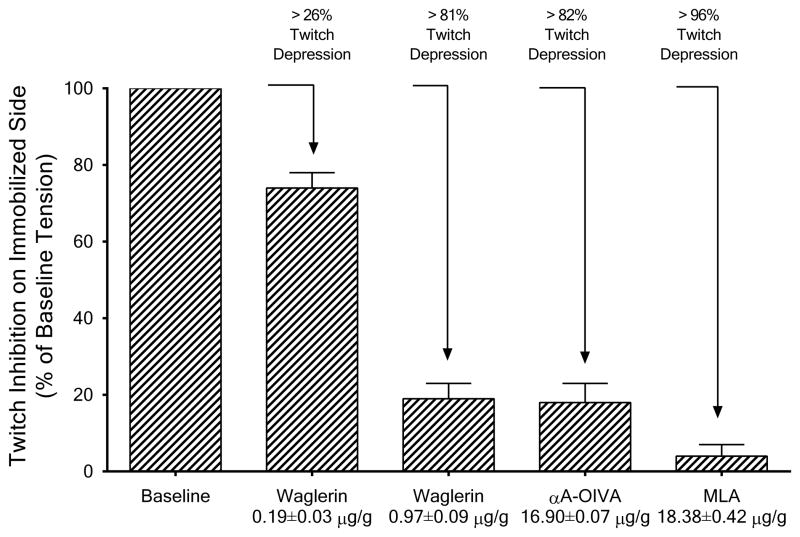

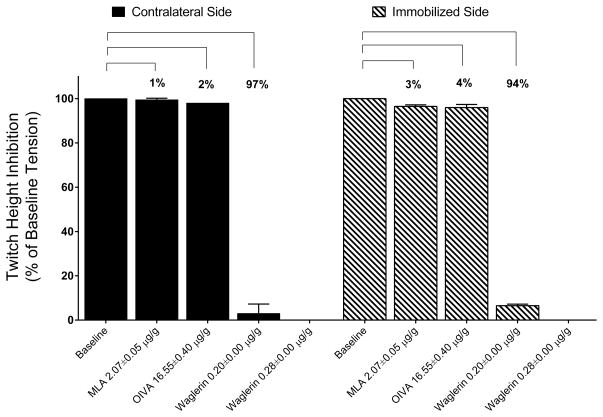

4. Characterization of the Role of α7AChRs in neurotransmission

For these set of experiments a total of 8 animals were immobilized and two were not used because of ineffective immobilization. In the first set of studies (n=3), following ~75–80% twitch depression with waglerin-1 (0.97 ± 0.09 μg/g) and OIVA (16.90 ± 0.07 μg/g) as described previously, methyllycaconitine was administered. Preliminary studies with methyllycaconitine indicated that the onset of effect of methyllycaconitine was relatively slow compared to waglerin-1. In other words, the effects of waglerin-1 on depression of tension were dissipating before onset of effect of methyllycaconitine. In view of the slower onset of methyllycaconitine, a relatively high dose was administered in order to produce a faster onset of effect. A total dose of 18.38 ± 0.42 μg/g caused almost complete suppression of the remaining twitch (Figure 3). In another group of animals (n=3) following stabilization of twitch tension, methyllycaconitine in a dose of 2 μg/g administered first caused 1–3% decreases in tension on the contralateral and immobilized side, respectively, in about 10 minutes (Figure 4). (The reason for this reverse order has been explained. See #6 of Methods). At this point, the administration of αA-OIVA caused minimal changes in twitch tension on either side. Waglerin (0.20 ± 0.00 μg/g), however, caused equal twitch depression on both sides and an additional dose of 0.08 ± 0.00 (total dose of 0.28 ± 0.00) caused complete twitch depression in both sides. In other words, once the α7AChRs were preemptively blocked by methyllycaconitine, the responses to waglerin-1 were similar on the two sides.

Figure 3. The α7 acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs) contribute to ~20% twitch tension.

In a separate set of animals (N=3), after stabilization of twitch tension, waglerin-1 and conotoxin, αA-OIVA were administered in doses indicated in the figure until no further twitch suppression. At this point methyllycaconitine (MLA), a specific antagonist of α7AChRs, administered incrementally totaling a dose of 18.38 ± 0.42 μg/g caused almost complete twitch suppression. Thus, ~20% of twitch tension during immobilization could be attributable to the nicotinic α7AChRs. Data are presented as percent.

Figure 4. Pre-block of α7 acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs) by methyllycaconitine causes equipotent responses to waglerin-1 on both sides.

In a separate set of animals (N = 3), a small dose of methyllycaconitine (MLA) (50 μg or 2.07 ± 0.05 μg/g) was administered first. This dose of methyllycaconitine caused minimal 1–3% twitch inhibition on both sides. After about 10 minutes, conotoxin, αA-OIVA (16.6 ± 0.40 μg/g) caused no changes in tension on either side. The subsequent administration of waglerin-1, in doses indicated in the figure, resulted in equipotent responses on immobilized and contralateral side. Thus, a total dose of 0.28 ± 0.00 caused complete twitch suppression on both sides. Data represented as percent of baseline twitch height.

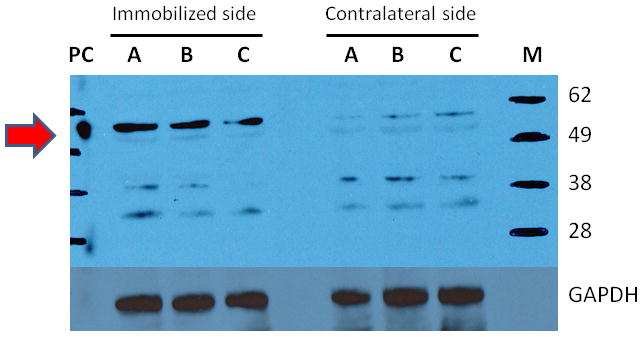

5. Protein expression of α7AChRs on muscle membrane

The following study quantified the expression of α7AChR protein on muscle membrane. Western blot analysis (Figure 5) revealed that the expression of α7AChRs was increased on the immobilized compared to contralateral side (24.1 ± 2.9 vs. 7.9 ± 1.3, arbitrary units, respectively, p < 0.01; N=3 for each side). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, used as loading control, did not differ between the two sides. Brain extract, used as positive control, confirmed the specificity of the antibody, where the α7AChRs were located at 55kD molecular weight.

Figure 5. Protein expression of α7 acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs) in muscle.

The tibialis muscles from immobilized and contralateral sides (N = 3 per side) previously harvested, were homogenized and subjected to immunoblots. Brain extract was used on positive control for α7AChRs, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehyrogenase (GAPDH) as the loading control. The letters M and PC indicate the molecular weight marker and positive control (Brain extract). The α7AChRs is located at 55kD molecular weight, indicated by the red arrow on the left. At 14 days after immobilization, the expression of α7AChRs was increased three fold compared to contralateral side.

DISCUSSION

The current study confirms the hypothesis that immobilization-induced muscle atrophy leads to de novo junctional-area expression of α7AChRs, which play a small but significant role in neurotransmission. The significantly decreased muscle mass and/or decreased tension generating capacity on the immobilized compared to the contralateral side (intra-subject control) in two different sets of animals confirmed the efficacy of the immobilization procedure used in these studies (Table 1 & Figure 1A). With use of specific antagonists to the mature and immature AChRs, we provide evidence that a third receptor not sensitive to waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA, but sensitive to α-BTX was present. The use of specific antagonist of α7AChRs, methyllycaconitine, confirmed that the third receptor insensitive to waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA was indeed α7AChRs. The immunoblot studies confirmed the expression of α7AChRs in the muscle membrane. Despite the well documented upregulation of immature AChRs on the muscle membrane during immobilization, our studies confirm the hypothesis that the immature AChRs play a minimal role in neurotransmission on the immobilized side.

The rodent model of immobilization has been described by us previously in rats,9–11 and most recently in mice.22 In those studies, it was demonstrated that the contralateral side behaves like naïve controls in terms of muscle function and muscle mass at 14 days of immobilization. With the use of pharmacologic probes, this study confirms that the unimmobilized contralateral side almost exclusively expresses mature receptors, evidenced by the ≥ 97% depression of tension with waglerin-1 only. The contribution of mature AChRs to neurotransmission, however, decreases on the immobilized side, as waglerin-1 could not completely depress the twitch tension to ≥ 80%. Although the upregulation of immature receptors on the muscle membrane has been demonstrated in many reports,8–12 this study demonstrates that immature AChRs contribute minimally to neurotransmission on both sides as αA-OIVA caused minimal changes in tension. In other words, the protein expression of functional immature AChRs is almost exclusively in the extra-junctional area. The fact that 20% of twitch height still remains after block with waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA suggests that this tension is maintained by receptors other than mature and immature AChRs.

Our preliminary studies with methyllycaconitine, indicated that its onset of effect was slow and duration of effect prolonged relative to onset and offset of waglerin-1 effect. Therefore, when methyllycaconitine was administered after waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA, methyllycaconitine was administered at a higher dose than when administered first. The higher dose was deliberately done in order to have a faster onset, prior to the dissipation of the effects of waglerin-1, evidenced by return of twitch height. (Higher doses of drug, particularly antagonists of muscle AChRs, can effect faster onset of paralysis3,5). In the subsequent experiment (Figure 4), however, methyllycaconitine was administered in a smaller dose (2 μg/g or 1/10th previous dose) at least 10 minutes prior to αA-OIVA and waglerin-1, giving sufficient time for onset of effect of methyllycaconitine. This dose caused minimal changes in twitch height. Once the α7AChRs were preemptively blocked by methyllycaconitine, waglerin-1 (0.3 ± 0.01 μg/g) was equipotent on both sides, which, therefore, reflects the pivotal role of α7AChRs in the resistance to the neuromuscular effects of waglerin-1. It is notable, that αA-OIVA (Figure 4) again did not cause changes in tension, confirming the insignificant junctional expression of immature AChRs. The fact that αBTX and methyllycaconitine blocked the twitch tension after block of mature and immature AChRs indicates that inhibition of the remaining 20% twitch tension was related to the non-specific and specific effects of αBTX and methyllycaconitine, respectively, on the α7AChRs. Thus, the present studies document for the first time that α7AChRs can be expressed even in innervated but pathologic muscle, and that these α7AChRs receptors, but not immature AChRs, play a role in neurotransmission on the immobilized side.

One may pose the question, why methyllycaconitine when administered first did not cause a greater twitch inhibition than observed? This question requires detailed explanation. Paton and Waud described the concept of margin of safety of neurotransmission in skeletal muscle. They determined that depression of twitch tension does not occur until antagonism (occupation) of ≥75% junctional receptors.26,27 In other words, an antagonist ligand will cause twitch inhibition only when ≥75% of the total AChRs are inhibited. Once the threshold of 75% receptor occupation is realized, twitch inhibition occurs. Since methyllycaconitine blocked only the α7AChRs, there were insufficient AChRs blocked to see significant effects on twitch tension. In other words, the junctional expression of α7AChRs is less than 75% of total junctional AChRs, explaining the lack of twitch inhibition, although α7AChRs contribute to ~20% twitch tension. Western blot analyses indicated a ≥ 3-fold increase in protein expression of α7AChRs on the immobilized muscle membrane compared to non-immobilized side (Figure 5A). Attempts to quantitate the increased expression of immature AChRs by immunoblot proved futile due to non-specific binding of the commercially available antibodies. No study has documented the presence of immature AChRs using commercial antibodies. Commercially available fluorescent probes for the α7AChRs also have non-specific binding, demonstrated by the binding of these probes to brains of α7AChR knockout mice.28,29 Thus, our study could not discriminate junctional versus extra-junctional expression of α7AChRs, because of the non-specific binding of the fluorescent probes. The twitch tension studies with specific antagonists, however, indicate junctional expression of α7AChRs, since extra-junctional receptors play no role in neurotransmission.

The most salient finding of α7AChRs expression in muscle during immobilization may have pharmacological and therapeutic implications. Resistance to the paralyzing (or neuromuscular) effects of clinically used muscle relaxants (pancuronium, atracurium) has been observed during immobilization, despite the disuse-induced muscle atrophy and muscle weakness.5,9,11 Although it has been postulated that the neuromuscular resistance to relaxants during immobilization is due to the expression of immature AChRs,3–5 the current study, documenting the absence of functional expression of immature AChRs causing neurotransmission, debunks the theory of the role of immature AChRs in the resistance to clinically used muscle relaxants. Consistently, oocyte expression studies confirm the lack of resistance to clinically used relaxants in vitro.30 We, therefore, posit that the resistance to clinically used muscle relaxants during immobilization is related to the expression of α7AChRs. This hypothesis is consistent with the ex vivo observation that denervation-induced resistance to pancuronium block observed in wild type mice was absent in α7AChR knock out mice.7 Relative to therapeutics, stimulation of α7AChRs has been shown to attenuates cytokine release and inflammation ex vivo and in vivo.24,31–33 Additional studies are needed to further characterize pharmacologic and therapeutic implications of α7AChR expression.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

Supported in part by grants from Shriners Hospitals for Children® Research Philanthropy, Tampa, FL, and National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (RO1 GM 05882 and P50-GM2500-Project 1) to JAJM. Dr. Lee was supported by In-Je Research and Scholarship Foundation, In Je Re University, Seoul, South Korea.

We are most grateful to Drs. R. W. Teichert and B. M. Olivera of the Department of Biology, University of Utah, for providing the initial quantities of waglerin-1 and αA-OIVA for performance of some of the preliminary studies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Albuquerque EX, Pereira FR, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalamida D, Poulas K, Avramopoulou V, Fostieri E, Lagoumintzis G, Lazaridis K, Sideri A, Zouridakis M, Tzartos SJ. Muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Structure, function and pathogenicity. FEBS Journal. 2007;275:3799–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martyn JAJ, Fagerlund MJ, Eriksson LI. Basic principles of neuromuscular transmission. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(Suppl 1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martyn JAJ, Richtsfeld M. Succinylcholine-induced hyperkalemia in acquired pathologic states: Etiologic factors and molecular mechanisms. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:158–69. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martyn JA, White DA, Gronert GA, Jaffe RS, Ward JM. Up-and-down regulation of skeletal muscle acetylcholine receptors. Effects on neuromuscular blockers. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:822–43. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199205000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer U, Reinhardt S. Expression of functional α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor during mammalian muscle development and denervation. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2856–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuneki H, Salas R, Dani JA. Mouse muscle denervation increases expression of an alpha7 nicotinic receptor with unusual pharmacology. Physiology. 2003;547:169–79. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fambrough DM. Control of acetylcholine receptors in skeletal muscle. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:165–227. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink H, Helming M, Unterbuchner C, Lenz A, Neff F, Martyn JAJ, Blobner M. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome increases immobility-induced neuromuscular weakness. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:910–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibebunjo C, Martyn JAJ. Fiber atrophy, but not changes in acetylcholine receptor expression, contributes to the muscle dysfunction after immobilization. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:275–85. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibebunjo C, Nosek MT, Itani MS, Martyn JAJ. Mechanisms for the paradoxical resistance to d-tubocurarine during immobilization-induced muscle atrophy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:443–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witzemann V, Brenner HR, Sakmann B. Neural factors regulate AChR subunit mRNAs at rat neuromuscular synapses. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:125–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McArdle JJ, Lentz TL, Witzemann V, Schwarz H, Weinstein SA, Schmidt JJ. Waglerin-1 selectively blocks the epsilon form of the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:543–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teichert RW, Garcia CC, Potian JG, Schmidt JJ, Witzemann V, Olivera BM, McArdle JJ. Peptide-Toxin Tools for Probing the Expression and Function of Fetal and Adult Subtypes of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1132:61–70. doi: 10.1196/annals.1405.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai MC, Hsieh WH, Smith LA, Lee CY. Effects of waglerin-I on neuromuscular transmission of mouse nerve-muscle preparations. Toxicon. 1995;33:363–71. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teichert RW, López-Vera E, Gulyas J, Watkins M, Rivier J, Olivera BM. Definition and Characterization of the Short αA-Conotoxins: A single residue determines dissociation kinetics from the fetal muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1304–12. doi: 10.1021/bi052016d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teichert RW, Rivier J, Dykert J, Cervini L, Gulyas J, Bulaj G, Ellison M, Olivera BM. AlphaA-Conotoxin OIVA defines a new alphaA-conotoxin subfamily of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor inhibitors. Toxicon. 2004;44:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Engisch KL, Teichert RW, Olivera BM, Pinter MJ, Rich MM. Prolongation of evoked and spontaneous synaptic currents at the neuromuscular junction after activity blockade is caused by the upregulation of fetal acetylcholine receptors. J Neuroscience. 2006;26:8983–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2493-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzoubi KH, Snivareerat M, Tran TT, Alkadhi KA. Role of α7- and α4β2-nAChRs in the neuroprotective effect of nicotine in stress-induced impairment of hippocampus-dependent memory. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 201(16):1105–13. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagihih R, Gfesser GA, Gopalakrishnan M. Advances in the discovery of novel positive allosteric modulators of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2007;2:99–106. doi: 10.2174/157488907780832751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiyar VN, Benn MH, Hanna T, Cacyno J, Roth SH, Wilkens JL. The principal toxin of delphinium brownii Rydb and its mode of action. Experientia. 1979;35:1367–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01964013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu S, Nagashima S, Khan MAS, Yasuhara S, Martyn JAJ. Lack of caspase-3 attenuates immobilization-induced muscle atrophy and loss of tension generation along with mitigation of apoptosis and inflammation. Muscle and Nerve. 2013;47:711–21. doi: 10.1002/mus.23642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt JJ, Weinstein SA, Smith LA. Molecular properties and structure-function relationships of lethal peptides from venom of Wagler’s pit viper, Trimeresurus wagleri. Toxicon. 1992;30:1027–36. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugita H, Kaneki M, Sugita M, Yas’ukawa T, Yasuhara S, Martyn JAJ. Burn injury impairs insulin-stimulated Akt/PKB activation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endo Metab. 2005;288:E585–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan MAS, Farkondeh M, Crombie J, Jacobson L, Kaneki M, Martyn JAJ. Lipopolysaccharide Up-regulates Alpha7 Acetylcholine Receptors: Stimulation with GTS-21 Mitigates Growth Arrest of Macrophages and Improves Survival in Burned Mice. Shock. 2012;38:213–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31825d628c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paton WD, Waud DR. The margin of safety of neuromuscular transmission. J Physiol. 1967;191:59–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paton WD, Waud DR. A quantitative investigation of the relationship between rate of access of a drug to receptor and the rate of onset or offset of action. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol. 1964;248:124–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00246668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herber DL, Severance EG, Cuevas J, Morgan D, Gordon MN. Biochemical and histochemical evidence of non-specific binding of α7nAChR antibodies to mouse brain tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:1367–76. doi: 10.1177/002215540405201013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moser N, Mechawar N, Jones I, Gochber-Sarver A, Orr-Urtreger A, Plomann M, Salas R, Molles B, Marubio L, Roth U, Maskos U, Winzer-Serhan U, Bourgeois JP, Le Sourd AM, De Biasis M, Schroder H, Lindstrom J, Maelicke A, Changeux JP, Wevers A. Evaluating the suitability of nicotnic acetylcholine receptor antibodies for standard immunodetection procedures. J Neurochem. 2007;102:479–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yost CS, Winegar BD. Potency of agonists and competitive antagonists on adult- and fetal-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1997;17:35–50. doi: 10.1023/A:1026325020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magne H, Savary-Auzeloux I, Vazeille E, Claustre A, Attaix D, Anne L, Veronique SL, Phillippe G, Dardevet D, Combaret L. Lack of muscle recovery after immobilization in old rats does not result from a defect in normalization of the ubiquitin-proteasome and the caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways. J Physiol. 2011;589:511–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosas-Ballina M, Tracey KJ. Cholinergic control of inflammation. J Intern Med. 2009;265:663–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radek RJ, Robb HM, Stevens KE, Gopalakrishnan M, Bitner RS. Effects of the novel alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist ABT-107 on sensory gating in DBA/2 mice: Pharmacodynamic characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;345:736–45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.197970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]