Abstract

Objectives

To identify baseline characteristics of patients with Scleroderma-Related Interstitial Lung Disease (SSc-ILD) which predict the most favorable response to a 12-month treatment with oral cyclophosphamide (CYC).

Methods

Regression analyses were retrospectively applied to the Scleroderma Lung Study data in order to identify baseline characteristics that correlated with the absolute change in %-predicted Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) and the placebo-adjusted change in %-predicted FVC over time (the CYC treatment effect).

Results

Completion of the CYC arm of the Scleroderma Lung Study was associated with a placebo-adjusted improvement in %-predicted FVC of 2.11% at 12 months which increased to 4.16% when patients were followed for another 6 months (p=0.014). Multivariate regression analyses identified the maximal severity of reticular infiltrates on baseline high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT), the modified Rodnan Skin Score (mRSS), and Mahler's Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) as independent correlates of treatment response. When patients were stratified based on whether 50% or more of any lung zone was involved by reticular infiltrates on HRCT and/or the presence of a mRSS of at least 23, a subgroup emerged with an average CYC treatment effect of 4.73% at 12 months and 9.81% at 18 months (p<0.001). Conversely, there was no treatment effect (−0.58%) in patients with less severe HRCT findings and a lower mRSS.

Conclusions

A retrospective analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study identified the severity of reticular infiltrates on baseline HRCT and the baseline mRSS as patient features that might predict responsiveness to CYC therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary disease has become the leading cause of death in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma, SSc), with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and pulmonary vascular disease representing the two primary lung manifestations (1). At present, only daily oral or pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (CYC) have been shown in large randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials to alter the course of SSc-ILD (2-3). While highlighting that SSc-ILD is treatable, the overall magnitude of the response to CYC in these studies was modest and the beneficial effects appeared to fade within a year after stopping treatment (2-4). When these features are combined with the potential toxicity associated with CYC (5), there has been considerable controversy about whether all patients with SSc-ILD should be treated or whether therapy should be reserved for patients at the greatest risk for progression or deterioration (6-8).

Until recently, information about disease risk and/or progression has come primarily from convenience cohorts and retrospective analyses (6, 9-12). These studies have confirmed that ILD is prevalent in SSc (40%-84% of patients) and that the extent of lung involvement significantly impacts on long-term survival. Out of 900 evaluable patients analyzed by Steen et al. (9) the presence of severe SSc-ILD was associated with a significant reduction in 10-year survival (58% survival) when compared to those without pulmonary involvement (87% survival). More recently, Goh et al. (6) reviewed high resolution computerized tomography (HRCT), forced vital capacity (FVC), and mortality data from 330 consecutive SSc patients. In their analysis, the extent of reticular changes on chest HRCT (>20% involvement) and the impact on pulmonary function (FVC <70%-predicted) yielded the best prediction of disease progression and long-term mortality. An increase in inflammatory cells on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) has also been suggested to predict progressive lung disease (12-13). However, the value of BAL cellularity as a predictor has been challenged by two recent studies in which BAL cellularity was found to correlate with the extent of disease at baseline but not with progression or the response to therapy (14-15).

In the recently completed Scleroderma Lung Study (3-4), 158 patients with dyspnea and SSc-ILD were prospectively treated in a randomized, double-blind, multi-center study with one year of CYC or placebo and the time course of %-predicted FVC was measured over a period of two years. Overall, assignment to the CYC arm was associated with a modest but statistically significant treatment effect at 12 months (3). We hypothesized that this database would provide a unique opportunity to evaluate baseline patient characteristics for their ability to predict the course of lung disease over time and the likelihood of responding favorably to CYC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Patients and Design

The Scleroderma Lung Study was a multi-center randomized and double-blinded trial comparing the course of %-predicted FVC over two years in SSc-ILD patients who were treated for the initial 12-months with either CYC or placebo and then followed for a second 12 months (3). All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution. Key entry criteria included the presence of diffuse or limited cutaneous SSc (dcSSc or lcSSc), disease duration of ≤ 7 years, restrictive lung disease (FVC <85% and >40% predicted), symptomatic dyspnea, and signs of active ILD as assessed by either HRCT and/or BAL criteria (3, 14, 16).

Chest HRCT scoring

Non-contrast HRCT scans were acquired in the prone position, end-inspiration, from the lung apices to bases with 1-2 mm collimation at 10-mm intervals as previously detailed (16). Scoring was carried out in a blinded manner by two independent thoracic radiologists and discordant scores reviewed with a third core reader (JG) to produce a final consensus score. Images from the right and left lung were each divided into 3 zones (upper, middle, and lower) and scored for the extent of pulmonary abnormalities using a 0-4 Likert scale (0%, 1-25%, 26-50%, 51-75% and 76-100% involvement). Images were assessed for pure ground-glass opacifications (GGO), reticular changes (fibrosis, FIB), and honeycomb cysts (HC) as previously defined (16 and Figure S1, online supplement). Mean and maximum (Max) scores for each abnormality were reported.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed at baseline in the right middle lobe by serially instilling and recovering four 60-ml aliquots of room-temperature saline (14). Cytospins were stained with Diff-Quick and the % neutrophils (PMN), eosinophils (EOS) and lymphocytes read centrally by two experienced readers.

Pulmonary function testing

Lung function was measured by study-certified technologists in accordance with published standards to determine FVC by spirometry, total lung capacity (TLC) by plethysmography, and single-breath diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), all expressed as percent of predicted (3). Pulmonary function outcomes were assessed every three months during the 2-year study period.

Statistical analysis

Eighteen months, 6 months after completing the 12 month course of either CYC or placebo, was previously identified as the time point of the maximal treatment response (4). As such, linear regression was used to correlate the change in %-predicted FVC from baseline to 18 months for each evaluable participant to their baseline features including demographic factors, pulmonary function, BAL cell counts, HRCT scores, skin involvement, symptoms, treatment assignment and interaction terms. Three different multivariate regression models were then assessed for their ability to predict the CYC treatment effect and identify baseline characteristics with independent predictive value. In a targeted model, baseline features found to have a univariate association with the change in %-predicted FVC (p≤0.10) were combined along with the baseline %-predicted FVC. An empiric model was also derived independently using the best subset selection approach in which 10 baseline characteristics were empirically selected based on the optimal adjusted R-square criterion (17). Predictive characteristics identified as potentially significant by either of these two models (p<0.05) were then combined to form a final consensus model.

Once a set of baseline predictors had been identified, a modified classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was used to identify a single cut-point for each of them which best divided the patients into two distinct subsets, one characterized as CYC responsive and the other as CYC non-responsive (18). Finally, time-trend curves that had been adjusted for %-predicted FVC at baseline were constructed to determine the impact of the final predictor strategy on the change in %-predicted FVC at different time points from 3 to 18 months.

RESULTS

Enrollment and baseline characteristics

Of the 158 eligible patients enrolled into the Scleroderma Lung Study, 145 (92%) had evaluable baseline and endpoint data at 3 months, 141 (89%) at 6 months, 136 (86%) at 9 and 12 months, 116 (73%) at 15 months, and 112 (71%) at 18 months. As previously reported (4), 18-month outcomes demonstrated the greatest separation in %-predicted FVC between the CYC and placebo arms and were therefore selected as the primary target for this analysis. Baseline features, deaths, treatment failures, and withdrawals were not significantly different between the two study arms as previously detailed (3-4). In addition, there were no significant differences between the baseline characteristics for the entire randomized population and the current cohort with evaluable data at 18 months. The 18-month cohort included 55 patients assigned to the CYC arm and 57 to the placebo arm with a mixture of lcSSc (39%) and dcSSc (61%), an average disease duration of 3.2 +0.9 years, moderate restrictive lung disease (FVC = 68.8 ±0.9%-predicted) and a severe impairment in gas transfer (DLCO = 42.6 ±1.0%-predicted). 71 of the 101 patients who underwent BAL met study criteria for alveolitis and 104 out of 108 patients who underwent HRCT imaging had abnormalities recorded. The complete profile of the 18-month cohort is presented in Table S1 (online supplement).

Univariate and multivariate correlations with the change in %-predicted FVC

As detailed in Table 1, treatment assignment, duration of SSc symptoms other than Raynaud's, maximal severity of reticular changes on HRCT (MaxFIB score), extent of skin involvement (modified Rodnan Skin Score; mRSS), and interaction terms between treatment assignment and scores for MaxFIB and mRSS, were all associated by univariate correlations (p≤0.10) with the change in %-predicted FVC from baseline to 18 months.

Table 1.

Univariate correlations* between baseline characteristics and the change in %-predicted FVC from 0 to 18 months.

| UNIVARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variables | Group | Coefficient | SEM | r2 | p-value† |

| Treatment Arm | |||||

| CYC‡ versus Placebo | All | 4.17 | 1.91 | 0.04 | (0.03) |

| Demographic | |||||

| Duration of SSc | All | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.03 | (<0.01) |

| CYC | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.28 | |

| Placebo | 1.05 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.18 | |

| Pulmonary Function | |||||

| %-predicted FVC | All | −0.01 | 0.08 | <0.01 | 0.95 |

| CYC | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.43 | |

| Placebo | −0.07 | 0.12 | <0.01 | 0.56 | |

| BAL Cell Counts | |||||

| % PMN | All | 0.03 | 0.16 | <0.01 | 0.87 |

| CYC | −0.16 | 0.24 | <0.01 | 0.52 | |

| Placebo | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.29 | |

| HRCT Scores | |||||

| MaxFIB Score | All | 0.51 | 0.97 | <0.01 | 0.60 |

| CYC | 2.43 | 1.44 | 0.05 | (0.10) | |

| Placebo | −0.90 | 1.25 | 0.01 | 0.47 | |

| Skin Involvement | |||||

| mRSS | All | 0.06 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.48 |

| CYC | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.05 | (0.10) | |

| Placebo | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.33 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| BDI | All | 0.08 | 0.55 | <0.01 | 0.89 |

| CYC | −1.15 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.17 | |

| Placebo | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.27 | |

| Interaction Terms | |||||

| FVC-CYC Arm | All | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.34 |

| Duration of SSc-CYC Arm | All | −0.41 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| MaxFIB-CYC Arm | All | 3.33 | 1.20 | 0.07 | (0.09) |

| mRSS-CYC Arm | All | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.07 | (0.07) |

All significant correlations (p≤0.10) and at least one baseline characteristic from each category are displayed.

p≤ 0.10 noted in bold with parentheses

Table abbreviations: CYC, cyclophosphamide; SSc, scleroderma; PMN, polymorphonuclear cells; mRSS, modified Rodnan Skin Score; BDI, Mahler's Baseline Dyspnea Index; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Three different multivariate regression models were constructed including a targeted model based on the positive findings from the univariate analysis, an empiric model that was independently developed using a best subset forward-selection approach, and a consensus model which combined the independent predictor characteristics identified by the targeted and empiric approaches (Table S2, online supplement). Both the targeted and empiric regression models identified assignment to the CYC arm and treatment interactions between CYC and the mRSS as independent and significant (p<0.05) correlates of the change in %-predicted FVC from 0 to 18 months. In the targeted model, a treatment interaction between CYC and MaxFIB score was also identified as an independent correlation, while in the empiric model treatment interactions between CYC and FVC, and between CYC and BDI, were identified as significant. To reconcile these differences, all of these factors were included in a final consensus model (Table 2), which identified CYC treatment as well as CYC treatment interactions with MaxFIB score, mRSS, and Mahler's Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) as significant independent predictors of the change in %-predicted FVC from 0 to 18 months. However, regardless of the multivariate model, no more than 14% of the outcome variability was accounted for by these approaches. As such, these predictors were relatively insensitive in their ability to predict the absolute change in %-predicted FVC over time.

Table 2.

Multivariate consensus regression model.

| Components of the Consensus Model | Coefficient | SEM | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYC Arm | 3.90 | 1.99 | (0.05) |

| FVC | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.45 |

| MaxFIB | −1.64 | 1.30 | 0.21 |

| mRSS | −0.21 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| BDI | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.21 |

| FVC-CYC Interaction | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| MaxFIB-CYC Interaction | 4.94 | 1.97 | (0.01) |

| mRSS-CYC Interaction | 0.39 | 0.19 | (0.05) |

| BDI-CYC Interaction | −2.44 | 1.11 | (0.03) |

p≤0.05 noted in bold with parentheses

Relationships between baseline features and the CYC treatment effect

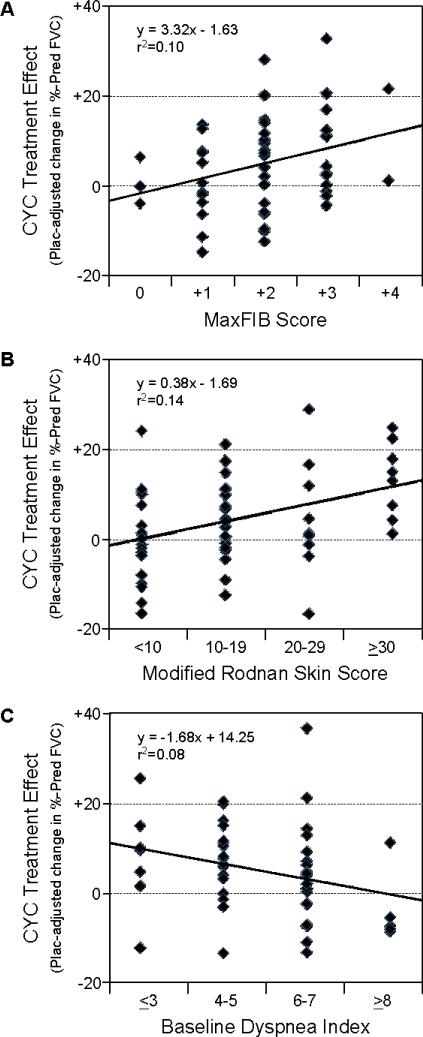

When assignment to the CYC arm was used as the only predictor of outcome, the overall CYC treatment effect at 18 months was statistically significant but modest in magnitude (4.16%; p=0.014). A central question for our analysis was whether this result was due to the limited potency of CYC or whether it might be due to a mixture of CYC responsive and non-responsive patients within the study population. To address this, the identified predictors of the change in FVC over time were evaluated for their relationship with the magnitude of the CYC treatment effect (Figure 1). MaxFIB score, mRSS, and the BDI were the only factors that significantly correlated with the placebo-adjusted change in %-predicted FVC. The higher the MaxFIB score or the mRSS at baseline, the greater the CYC treatment effect. Conversely, the higher the BDI score (indicating less dyspnea) the less the CYC treatment effect. In contrast, while the baseline %-predicted FVC, duration of SSc, and DLCO exhibited some utility in predicting the change in FVC over time for all subjects, none of these factors were significantly related to the CYC treatment effect (Figure S2, online supplement).

Figure 1. Predictors of the CYC treatment effect at 18 months.

Baseline values for the (A) maximal severity of reticular changes on HRCT (MaxFIB score), (B) modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) and (C) Mahler's baseline dyspnea index (BDI) were divided into clinically-relevant groups and plotted against the placebo (Plac)-adjusted treatment effect at 18 months (the change in %-predicted FVC from baseline to 18 months in the CYC arm minus the change observed in the same subset in the placebo arm). All of these baseline characteristics demonstrated a significant correlation with FVC outcome (p<0.05).

Clinically-relevant classification and regression tree model

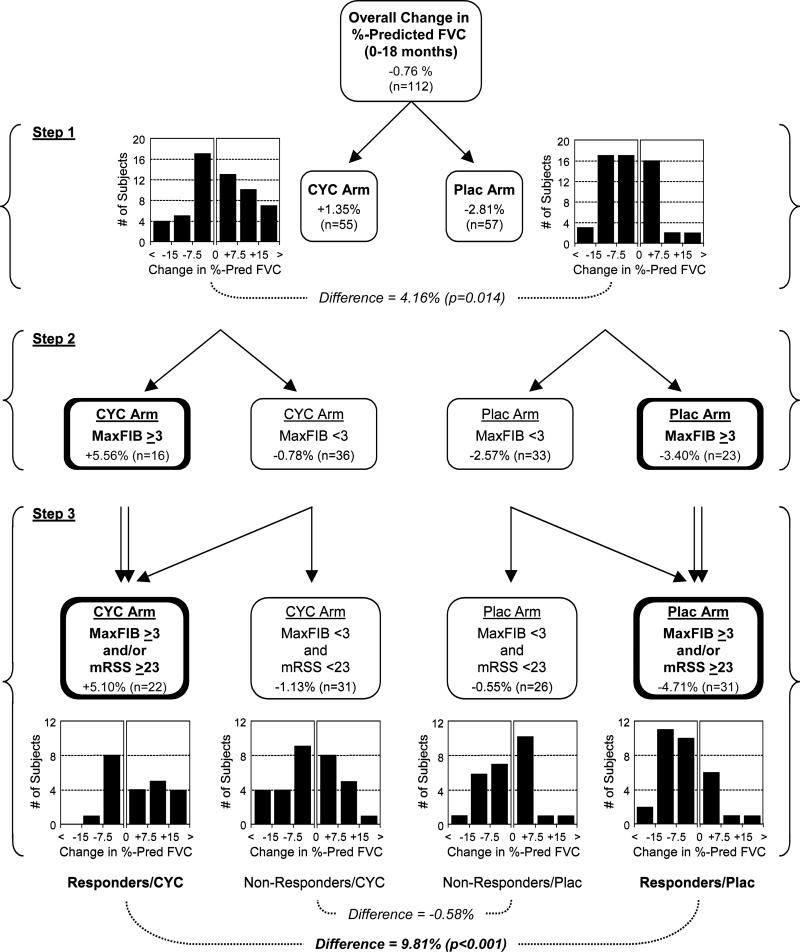

We next assessed whether identified predictors of the CYC treatment effect could be used to classify patients into two distinct clinical groups; treatment responders and non-responders. A modified CART model was used to identify clinically-relevant cut-points for the MaxFIB, mRSS, and BDI scores with the goal of distinguishing responders from non-responders (Figure 2). In Step 1 of the CART model, study patients were dichotomized solely on their treatment assignment (CYC versus placebo). This produced the overall treatment effect averaging 4.16% (p=0.014). In the second level of the regression tree analysis, CART modeling identified a MaxFIB score on HRCT of 3 (≥50% involvement of any lung region by reticular changes) as the optimal cut-point to stratify subjects into CYC responsive and CYC non-responsive subsets. In the subgroup with higher MaxFIB scores, the CYC treatment effect was much greater, resulting in an 8.96% difference in %-predicted FVC between the CYC and placebo study arms. In Step 3, the CART model further divided subjects according to the extent of skin involvement (mRSS). While this produced 4 potential subgroups within each treatment arm, three of these subgroups (MaxFIB score ≥3 and mRSS ≥23; MaxFIB score ≥3 and mRSS ≤23; and MaxFIB Score ≤3 and mRSS ≥23) were associated with an improved CYC treatment effect while one was not (MaxFIB score <3 and mRSS <23). The three similar subgroups were therefore combined (MaxFIB score ≥3 and/or mRSS ≥23), again resulting in one subset of potential CYC responders and one subset of potential CYC non-responders. Using this stratification, the average CYC treatment effect in the CYC responsive subset increased further to 9.81%-predicted FVC (p<0.001), while the average CYC treatment effect in the CYC non-responsive subset decreased to −0.58%-predicted FVC. Addition of the BDI score as a fourth level of stratification, in which subjects with less-severe dyspnea (BDI >7) were moved from the responsive to the non-responsive subset, further boosted the treatment effect to 11.59% in the CYC responsive population. However, this substantially limited the number of study patients meeting criteria for CYC responders (from 53 to 40) and was associated with a modest decrease in statistical significance when comparing the CYC and placebo arms (data not shown). As a result, the addition of this fourth factor (the BDI) was not considered to substantially improve the clinical value of the prediction model.

Figure 2. Multivariate tree regression analysis.

In Step 1, the study population was dichotomized into those assigned to the CYC versus placebo arms. The mean change in %-predicted FVC from 0 to 18 months is indicated, as are the applicable subjects numbers (N) and histograms demonstrating the number of subjects with different ranges of change in %-predicted FVC. The difference between groups and the resulting p-value are also shown. In Step 2, each group was further subdivided into two subsets based on the MaxFIB score. In Step 3, subjects were again subdivided based on their mRSS score. Rather than dividing each treatment arm into 4 different subsets, subjects with a MaxFIB score ≥3 and/or a mRSS ≥23 were pooled into one group and subjects with a MaxFIB score <3 and a mRSS <23 were left as the alternative grouping. When the resulting populations were compared, a CYC responsive group was identified with an average treatment effect of 9.81%. Conversely, the subset with a low MaxFIB score and a low mRSS demonstrated no significant CYC treatment effect.

Time-trend analysis

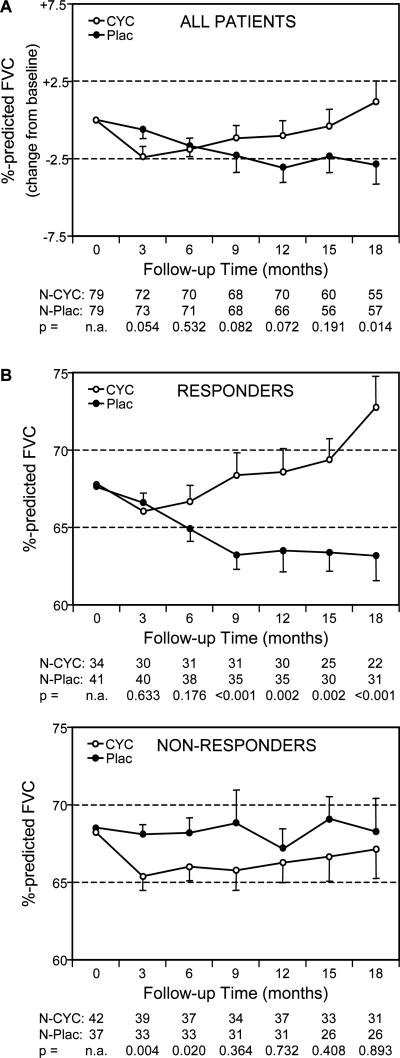

A time-trend analysis was carried out to address several potential limitations that were inherent in our analysis. First, because 29% of the enrolled patients did not have FVC measurements at 18 months (due to their early withdrawal, treatment failure or death), their responses to CYC were not included in our modeling. Second, by focusing on only one point in time (18 months), there was no assurance that our predictive algorithm would apply to treatment responses at other points in the study. Finally, the focus on treatment effect (difference in %-predicted FVC between the CYC and placebo arms) provided little insight into the course of disease over time. We therefore plotted the %-predicted FVC for each treatment arm at various time points in the study from 3 to 18 months using data from all evaluable patients at each time point (Figure 3). Compared to the unselected patient population, stratification of the participants based on the combination of their MaxFIB score and mRSS resulted in two subgroups with distinctively different time-trend plots. The subgroup classified as potential CYC responders (MaxFIB score ≥3 and/or mRSS ≥23) demonstrated a consistent and marked separation over time between the CYC and placebo arms. There was a clear divergence between the CYC and placebo arms starting as early as 6 months (when data from 88% of randomized patients were included) which steadily increased through 18 months. Within this subgroup, assignment to the placebo arm resulted in significant deterioration of pulmonary function over time while assignment to the CYC arm was associated with a significant improvement in pulmonary function over time (p<0.05). In contrast, the subgroup classified as CYC non-responders exhibited relatively stable FVC values over time without a significant impact of treatment assignment on the FVC outcome.

Figure 3. Time-trend curves.

The changes in %-predicted FVC from baseline to 18 months (adjusted for baseline FVC) are plotted for the cyclophosphamide (CYC) and placebo (Plac) arms (mean ±SEM). The number of subjects (N) at each time-point and the p-value comparing groups is presented. (A) There was a small but significant difference between the treatment arms at 18 months when results were plotted for all patients. (B) Dividing the study population into Responder and Non-responder subsets resulted in two distinct plots with a highly-significant treatment effect from 9 to 18 months occurring only in the Responder population.

Taking the utility of the time-trend approach one step further, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which all early withdrawals, treatment failures and deaths were considered as indicators of a poor response to therapy and therefore automatically assigned to the non-responder subset. This re-assignment had no substantial impact on the course of disease over time in either the responder or non-responder groups. The average %-predicted FVC values for the CYC and Plac arms of the responder population still separated in the same manner at 9, 12, 15 and 18 months (p<0.001 at all time points), while there was no significant difference in %-predicted FVC between treatment groups in the non-responder population at the same time points (p=0.44; 0.70; 0.31; and 0.89, respectively).

Characteristics of the CYC responsive and CYC non-responsive phenotypes

Evaluable patients from the 18-month cohort were retrospectively stratified into 53 patients with a CYC responsive phenotype (MaxFIB score ≥3 and/or mRSS ≥23) and 57 patients with a CYC non-responsive phenotype (MaxFIB score <3 and mRSS <23) in order to assess the impact of this stratification on the distribution of other baseline characteristics (Table 3). Interestingly, the baseline measures of pulmonary function (FVC, TLC and DLCO) were all significantly worse in the potential CYC responders, as were the frequency of eosinophils on BAL, the maximal severity of honeycomb changes on HRCT, and the health assessment disability index. However, there was considerable overlap between the CYC responsive and non-responsive groups with respect to all of these features (data not shown), likely explaining why they were not identified as significant independent predictors of treatment outcome.

Table 3.

Phenotype of CYC Responsive and Non-Responsive subgroups.

| CHARACTERISTICS | Unselected Patients | Predicted as CYC Responsive (MaxFIB ≥3 and/or mRSS ≥23) | Predicted as CYC Non-Responsive (MaxFIB <3 and mRSS <23) | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Number | 112 | 53 | 57 | |

| Age, yrs | 46.9 (0.9)* | 47.5 (1.5) | 46.2 (1.5) | 0.56 |

| Male, % | 29.5 | 34.0 | 26.3 | 0.38 |

| Duration of SSc, yrs | 3.2 (0.2) | 3.12 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.3) | 0.51 |

| Smoking history, % | 34% | 29% | 39% | 0.25 |

| Pulmonary Function | ||||

| FVC, %-predicted | 68.8 (0.9) | 65.8 (1.6) | 71.6 (1.5) | (<0.01) |

| TLC, %-predicted | 69.8 (1.1) | 67.2 (1.8) | 73.5 (1.8) | (0.02) |

| DLCO, %-predicted | 47.6 (1.0) | 42.6 (1.6) | 52.3 (1.5) | (<0.01) |

| BAL Cell Counts | ||||

| % PMN | 5.90 (0.51) | 7.06 (0.85) | 5.08 (0.86) | 0.13 |

| % EOS | 2.89 (0.34) | 3.90 (0.75) | 2.10 (0.34) | (0.03) |

| HRCT Scores | ||||

| MaxGGO, 0-4 scale | 0.69 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.09) | 0.72 (0.11) | 0.62 |

| MaxFIB, 0-4 scale | 1.95 (0.08) | 2.65 (0.13) | 1.33 (0.09) | NA |

| MaxHC, 0-4 scale | 0.37 (0.04) | 0.51 (0.07) | 0.25 (0.07) | (0.01) |

| Skin Involvement | ||||

| mRSS, 0-51 scale | 14.9 (0.8) | 19.2 (1.7) | 10.9 (0.9) | NA |

| dcSSc, % | 61.6 | 64.2 | 57.9 | 0.50 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| BDI, 0-12 scale | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.3) | 5.2 (0.2) | 0.29 |

| HAQ-DI, 0-3 scale | 0.81 (0.06) | 0.97 (0.11) | 0.62 (0.07) | (<0.01) |

(SEM)

Comparison of the “Predicted as CYC Responsive” and “Predicted as CYC Non-Responsive” subsets by t-test or chi-square. p≤0.05 noted with parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Treatment with one year of oral CYC in the Scleroderma Lung Study improved pulmonary function, dyspnea, reticular changes on HRCT, and skin disease when compared to the effects of placebo (3-4, 19-20). While these beneficial effects were wide-ranging, the overall magnitude of change in FVC was small and dissipated by the end of 24-months (3-4). A small but beneficial effect of intravenous CYC on lung function was also suggested by the Fibrosing Alveolitis in Scleroderma Trial (2). Based on these studies and the known side effects of CYC, some investigators have concluded that the potential risks from CYC outweigh the benefits (5, 7-8). Others have hypothesized that CYC would be more effective if targeted for use in a select subset of patients (6, 21-22). This controversy stimulated our retrospective analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study with the goal of identifying predictors of the CYC treatment effect. Using a combination of regression analyses we identified two mutually exclusive sub-groups based on the severity of reticular infiltrates on HRCT (MaxFIB score) and/or the extent of skin disease (mRSS). One population, described in this report as CYC responsive and representing 49% of enrolled subjects, were identified by the presence of more advanced reticular disease on baseline HRCT and/or more extensive skin involvement (MaxFIB score ≥3 and/or mRSS ≥23). On average, these patients also had more extensive pulmonary function abnormalities, a greater percentage of inflammatory cells on BAL, and worse disability scores at baseline than non-responders. In contrast, non-responders were defined by the presence of relatively limited lung and skin involvement (MaxFIB score <3 and mRSS <23). When divided into these distinct subsets, the average CYC treatment effect in the responder population was a striking 9.81% improvement in %-predicted FVC at 18 months, while there was no obvious benefit from CYC in the non-responders (a −0.58% difference between the CYC and placebo groups). Similarly, meeting the baseline criteria for being CYC responsive was associated with a 5.4 point placebo-adjusted improvement in the mRSS at 18 months (p=0.008), while meeting the criteria for non-responders resulted in only a 1.1 point difference in the mRSS (p=0.488). If confirmed by additional studies, these responder and non-responder criteria could have an important impact on how we view the selection and treatment of SSc-ILD.

The prevailing theory is that CYC can slow the progression of SSc-ILD but cannot reverse it. As such, investigators have hypothesized that its effectiveness will be most evident in the subset of patients at the greatest risk for future deterioration (6-7, 21-22). Based on a longitudinal analysis of 215 SSc-ILD patients, Goh et al. (6) proposed that the extent of lung involvement on HRCT (>20% involvement of the lung by reticular infiltrates) and pulmonary function tests (FVC <70%-predicted) can be used to identify this target population. The literature also frequently cites the finding by Steen et al. (9), where the duration of SSc was found to be a key predictor of the rate of lung deterioration. Our findings support all of these predictions to some degree, but not all were found to predict treatment response. In reviewing the time-trend curves presented in Figure 3 there is an obvious link between the risk for progressive lung disease and the likelihood of responding to CYC. Patients defined as potential responders and randomized to the placebo arm experienced a progressive and significant decline in FVC over time. In contrast, patients categorized as non-responders exhibited a relatively stable FVC throughout the study. Our findings also support the extent of reticular changes on HRCT as a predictor of both disease progression (the change in FVC over time) and the CYC treatment effect. While it is difficult to compare different HRCT outcome measures, the MaxFIB score described in this report appears to play a similar predictive role as the HRCT staging described by Goh et al. (6). As in other studies, we identified baseline FVC and the duration of SSc as potential predictors of the change in FVC over time. However, these two factors were not identified as independent predictors in our multivariate consensus model and also failed to predict the CYC treatment effect. Instead, our analysis identified the mRSS and BDI as novel predictors of the CYC treatment effect. This discrepancy between predictors of lung deterioration and predictors of treatment response suggests that these two outcomes overlap but are not identical. Indeed, as detailed in Figure 2, there were patients with significant lung deterioration in both the responder and non-responder categories.

The unique outcomes identified in this study were made possible by the randomized placebo-controlled design of the Scleroderma Lung Study. While convenience cohorts and longitudinal datasets often have the advantage of a larger sample size, their analysis is hindered by the inherent heterogeneity of patients, differences in treatment, and a marked variability in the timing, frequency and standardization of outcome measures. More importantly, the Scleroderma Lung Study allowed us to directly focus on the placebo-adjusted treatment effect. As noted in the results, correlations between baseline features and the course of %-predicted FVC over time were weak and never accounted for more than 14% of the subject-to-subject variability. However, by focusing on predictors of the CYC treatment effect, the MaxFIB score, mRSS and the BDI emerged as much more significant predictors of this outcome. Finally, when these individual predictors were integrated together with the overall effects of CYC using a step-wise CART analysis, they allowed us to identify two distinct groups of subjects; CYC responders and non-responders. As already noted, these two groups have many unique features and experienced markedly different treatment responses.

While the implications stemming from this analysis are potentially important, they are derived from a retrospective analysis of a single clinical trial and therefore require some form of independent confirmation. The predictor analysis by Goh et al. (6) adds credence to the use of HRCT measures of reticular lung disease as a predictor. Furthermore, the MaxFIB score was identified as an important covariate in the primary outcome analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study (3). While the extent of skin disease has not previously been shown to predict treatment responses in the lung, it has been closely correlated with the presence and extent of SSc-ILD in several recent studies (23-24). In addition, both lung and skin disease appear to respond to CYC therapy (3-4, 14, 16), further suggesting that these features are linked.

In addition to the need for further validation, other potential limitations exist that might prevent the translation of these findings into clinical practice. The Scleroderma Lung Study employed a standardized image acquisition protocol and experienced Core readers for the HRCT analysis (16). Given the inherent variability in clinical HRCT readings, it may be difficult to reproduce our findings in the clinic. Further, as already noted, it is hard to relate our HRCT measures to others that have been reported in the literature. The use of automated computer algorithms to standardize HRCT results may provide one way to address this (25). The same comments apply to the mRSS, which has been primarily used for research studies rather than as a clinical tool (26). Furthermore, use of the mRSS as a predictor might be misleading if taken out of context. When considered alone, the mRSS cutoff of ≥23 seems to imply that only patients with dcSSc are likely to respond to CYC. However, as already described in detail, this is not the case (20). According to our model, the primary definition of a responder is based on the presence of reticular changes on their HRCT. As such, if lcSSc patients exhibit significant lung disease they are just as likely to respond regardless of their limited skin involvement. However, patients with dcSSc are likely to respond if they exhibit extensive lung disease or if they exhibit milder lung disease but extensive skin disease. Finally, because treatment interactions with CYC were a central feature of our analysis, it is not clear whether the same predictors will apply when other forms of therapy are considered (7).

In summary, a multivariate regression analysis applied to the Scleroderma Lung Study in a retrospective manner identified the MaxFIB score, mRSS and BDI as independent correlates of the change in %-predicted FVC over time and the CYC treatment effect. When combined into a clinically relevant set of selection criteria, we identified two different patient subsets. One population, exhibiting more severe reticular changes on HRCT (MaxFIB score ≥3) and/or greater skin involvement (mRSS ≥23), appeared to be CYC responsive with an average treatment effect approaching a 10% difference in %-predicted FVC along with a 5.4 point improvement in their mRSS. In contrast, patients characterized by a combination of less severe HRCT changes and less extensive skin involvement exhibited relatively stable lung function and skin disease over time without an obvious CYC treatment response. These findings suggest the presence of distinct disease phenotypes and may provide an approach for targeting therapy to the most responsive subjects. However, as noted, there are several caveats to these conclusions and further validation and clinical development are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MD Roth and C-H Tseng contributed to this manuscript as co-principal authors. The Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group represents the following individuals, listed by participating site or Committee:

University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA (UO1 HL 60587 & UO1 HL 60606 for DCC): Philip J. Clements, MD, MPH; Donald P. Tashkin, MD; Robert Elashoff, PhD; Jonathan Goldin, MD, PhD; Michael Roth, MD; Daniel Furst, MD; Ken Bulpitt, MD; Dinesh Khanna, MD; Wen-Ling Joanie Chung, MPH; Sherrie Viasco, RN; Mildred Sterz, RN, MPH; Lovlette Woolcock; Xiaohong Yan, MS; Judy Ho, Sarinnapha Vasunilashorn; Irene da Costa

University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ (UO1 HL 60550): James R. Seibold, MD*; David J. Riley, MD; Judith K. Amorosa, MD; Vivien M. Hsu, MD; Deborah A. McCloskey, BSN; Julianne E. Wilson, RN; *Current address: University of Michigan Scleroderma Program, Ann Arbor, MI

University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (UO1 HL 60895): John Varga, MD; Dean Schraugnagel, MD; Andrew Wilbur, MD; David Lapota, MD; Shiva Arami, MD; Patricia Cole-Saffold, MS

Boston University, Boston, MA (UO1 HL 60682): Robert Simms, MD; Arthur Theodore, MD; Peter Clarke, MD; Joseph Korn, MD; Kimberley Tobin, Melynn Nuite BSN

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC *(UO1 HL 60750): Richard Silver, MD; Marcie Bolster, MD; Charlie Strange, MD; Steve Schabel, MD; Edwin Smith, MD; June Arnold; Katie Caldwell; Michael Bonner

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (UO1 HL 60597): Robert Wise, MD; Fred Wigley, MD; Barbara White, MD; Laura Hummers, MD; Mark Bohlman, MD; Albert Polito, MD; Gwen Leatherman, MSN; Edrick Forbes, RN; Marie Daniel

Georgetown University, Washington, DC (UO1 HL 60794): Virginia Steen, MD; Charles Read, MD; Cirrelda Cooper, MD; Sean Wheaton, MD; Anise Carey; Adriana Ortiz

University of Texas Houston, Houston, TX (UO1 HL 60839): Maureen Mayes, MD, MPH; Ed Parsley, DO; Sandra Oldham, MD; Tan Filemon, MD; Samantha Jordan, RN; Marilyn Perry

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (UO1 HL 60587): Kari Connolly, MD; Jeffrey Golden, MD; Paul Wolters, MD; Richard Webb, MD; John Davis, MD; Christine Antolos; Carla Maynetto

University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT (UO1 HL 60587): Naomi Rothfield, MD; Mark Metersky, MD; Richard Cobb, MD; Macha Aberles, MD; Fran Ingenito, RN; Elena Breen

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI (UO1 HL 60839): Maureen Mayes, MD, MPH*; Kamal Mubarak, MD; Jose L Granda, MD; Joseph Silva, MD; Zora Injic, RN, MS; Ronika Alexander, RN. *Present address: University of Texas Houston, Houston, TX

Virginia Mason Research Center, Seattle, WA (UO1 HL 60823): Daniel Furst, MD *; Steven Springmeyer, MD; Steven Kirkland, MD; Jerry Molitor, MD; Richard Hinke, MD; Amanda Mondt, RN *Present address: University of California at Los Angeles, CA

University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL (UO1 HL 60748): Mitchell Olman, MD; Barri Fessler, MD; Colleen Sanders, MD; Louis Heck, MD; Tina Parkhill

Data Safety and Monitoring Board members: Taylor Thompson, MD (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA); Sharon Rounds, MD (VA Medical Center, Brown University, Providence, RI); Michael Weisman, MD (Cedars Sinai/UCLA, Los Angeles, CA); Bruce Thompson, PhD (Clinical Trials Surveys, Baltimore, MD)

Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee members: Harold Paulus, MD (UCLA); Steven Levy, MD (UCLA); Donald Martin, MD (Johns Hopkins University).

Financial Support: This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant R01 HL089758 and R01 HL089901) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant R01-AR055075). Cyclophosphamide was provided by Bristol-Meyers-Squib at no charge.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial relationships to disclose that would create a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:940–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, Lees B, Newlands P, Goh NS, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3962–70. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Roth MD, Furst DE, Silver RM, et al. Effects of 1-year treatment with cyclophosphamide on outcomes at 2 years in scleroderma lung disease. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1026–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez FJ, McCune WJ. Cyclophosphamide for scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2707–09. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna D, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Tashkin DP, Eckman MH. Oral Cyclophosphamide for Active Scleroderma Lung Disease: A Decision Analysis. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):926–37. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08317015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nannini C, West CP, Erwin PJ, Matteson EL. Effects of cyclophosphamide on pulmonary function in patients with scleroderma and interstitial lung disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational prospective cohort studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):R124. doi: 10.1186/ar2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steen VD, Conte C, Owens GR, Medsger TA., Jr Severe restrictive lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1283–89. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, Sebastiani M, Michelassi C, La Montagna G, et al. Systemic Sclerosis; Demographic, clinical and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Med. 2002;81:139–53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benan M, Hande I, Ongen G. The natural Course of Progressive Systemic Sclerosis Patients with Interstitial Lung Involvement. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:349–54. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White B, Moore WC, Wigley FM, Xiao HQ, Wise RA. Cyclophosphamide is associated with pulmonary function and survival benefit in patients with scleroderma and alveolitis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:947–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-12-200006200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silver RM, Miller KS, Kinsella MB, Smith EA, Schabel SI. Evaluation and management of scleroderma lung disease using bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Med. 1990;88:470–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90425-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strange C, Bolster MB, Roth MD, Silver RM, Theodore A, Goldin J, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and response to cyclophosphamide in scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):91–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-655OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh NS, Veeraraghavan S, Desai SR, Cramer D, Hansell DM, Denton CP, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage cellular profiles in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease are not predictive of disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):2005–12. doi: 10.1002/art.22696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldin JG, Lynch DA, Strollo DC, Suh RD, Schraufnagel DE, Clements PJ, et al. High-resolution CT scan findings in patients with symptomatic scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2008;134:358–67. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller AJ. Subset selection in regression, second edition. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; New York (NY): 2002. pp. 1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone C. Classification and regression trees. Chapman and Hall; Boca Raton (FL): 1998. pp. 1–358. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldin J, Elashoff R, Kim HJ, Yan X, Lynch D, Strollo D, et al. Treatment of scleroderma-interstitial lung disease with cyclophosphamide is associated with less progressive fibrosis on serial thoracic high-resolution CT scan than placebo: findings from the scleroderma lung study. Chest. 2009;136(5):1333–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clements PJ, Roth MD, Elashoff R, Tashkin DP, Goldin J, Silver RM, et al. Scleroderma lung study (SLS): differences in the presentation and course of patients with limited versus diffuse systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(12):1641–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniou KM, Wells AU. Scleroderma lung disease: evolving understanding in light of newer studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(6):686–91. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283126985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beretta L, Caronni M, Raimondi M, Ponti A, Viscuso T, Origgi L, et al. Oral cyclophosphamide improves pulmonary function in scleroderma patients with fibrosing alveolitis: experience in one centre. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(2):168–72. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanitsch LG, Burmester G-R, Witt C, Hunzelmann N, Genth E, Krieg T, et al. Skin sclerosis is only of limited value to identify SSc patients with severe manifestations – an analysis of a distinct patient subgroup of the German Systemic Sclerosis Network (DNSS) Register. Rheumatol. 2009;48:70–3. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assassi S, Sharif R, Lasky RE, McNearney TA, Estrada-Y-Martin RM, Draeger H, et al. Predictors of interstitial lung disease in early systemic sclerosis: a prospective longitudinal study of the GENISOS cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):R166. doi: 10.1186/ar3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HJ, Li G, Gjertson D, Elashoff R, Shah SK, Ochs R, et al. Classification of parenchymal abnormality in scleroderma lung using a novel approach to denoise images collected via a multicenter study. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(8):1004–16. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czirjak L, Nagy Z, Arringer M, Riemekasten G, Matucci-Cerinic M, Furst DE, et al. The EUSTAR model for teaching and implementing the modified Rodnan skin score in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:966–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]