Introduction

Medication use in nursing homes (NH) occurs under some of the most complex circumstances in all of medicine. Most NH residents are frail with multiple medical conditions typically related to cardiovascular disease, arthritis, stroke and diabetes.1, 2 Nearly half are over the age of 85 and have disabling dementia that impairs their ability to communicate or perform daily activities.3 NH residents also receive, on average, seven to eight medications each month, putting them at high risk of medication-related problems including use of inappropriate therapies.1, 2, 4, 5

NHs may also be one of the most difficult settings in which to improve medication use. The challenge of poor NH prescribing quality is well documented and includes the underuse of indicated medications, overuse of harmful or ineffective medications, and failure to adequately and appropriately monitor narrow therapeutic window medications such as warfarin.1 Prior efforts to improve NH prescribing include academic detailing,6 audit and feedback to physicians,7 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling with ‘black box’ warnings for high risk drugs,8, 9 and federal policy proscribing drug appropriateness for NH residents.10 Despite these efforts, the problem of suboptimal NH prescribing persists. To illustrate this point, we focus on the example of antipsychotic medications.

Antipsychotics are widely used in the NH setting and have become the dominant therapeutic modality in NHs for treatment of behavioral symptoms of dementia despite clinical trial evidence showing little benefit for behavioral management11, 12 and growing evidence of excessive morbidity and mortality.8, 12, 13 In fact, the growth of atypical antipsychotic use between 1999 and 2006,14 despite federal regulations10 and FDA15 warnings calling for greater restraint in antipsychotic use among older adults suggests that the overuse of antipsychotics in NHs represents one of the great failures of evidence–based medicine to date.

This commentary describes a framework for improving prescribing in NHs by focusing on the whole facility as a system that has created a “prescribing culture.” We offer this paradigm as an alternative to targeted interventions that focus on educating and reforming “bad” prescribers, using the example of the atypical antipsychotics to illustrate the approach. We highlight elements of the NH culture change movement that are germane to medication prescribing, and illustrate which elements of NH culture have been shown to be associated with suboptimal quality of care. We conclude by describing current models including our study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to identify the best methods of disseminating evidence-based medication use guides in NHs.

Example: High Use of Antipsychotics in NHs

Approximately one-quarter to one-third of NH residents in the United States currently receive antipsychotic drugs.14, 16 This is the highest level of use reported in more than a decade. This affects the health and welfare of approximately 390,000 frail, institutionalized elders, with wide geographic variation in the United States ranging from approximately 20% to 45%. (Figure 1) In 2006, antipsychotics had become the most costly drug class for the Medicaid program, a main payer of NH medications,17 including $176 million in Medicaid reimbursements for dual eligibles and an additional $2.6 billion for nondual eligibles. By 2007, antipsychotic drugs were the third-largest therapeutic class in U.S. sales for all payers combined, accounting for over $13 billon in sales.18 Overall sales for antipsychotics followed only lipid-lowering agents and proton pump inhibitors, and experienced a growth in prescription sales of 12.1% between 2006 and 2007.

Figure 1.

State-level prevalence of any antipsychotic use in nursing homes in the United States, 2005 and 2006.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from a nationwide sample of nursing home residents in 48 states served by one pharmacy provider. Sample size included 1,068,104 residents. Methods described in Chen et al. [16]

Up to 80% of antipsychotics prescribed in NHs are for off-label uses, mainly for the management of the behavioral symptoms associated with advanced dementia.11,14,16,19 In 2006, a significant proportion of NH residents with dementia were prescribed an antipsychotic, including 22.6% without behavioral symptoms, 29.5% with non-aggressive behavioral symptoms, and 51.2% with aggressive behavioral symptoms.14 Essentially, most use was for residents without an FDA-approved indication, with as many as 21% of all NH residents in the US receiving antipsychotics without a psychosis-related diagnosis.14,16

The evidence base for using antipsychotics in the NH setting is limited and mostly extrapolated from what is known about treatment effects in community-dwelling adults. The landmark National Institutes of Health sponsored randomized clinical trial on atypical antipsychotics in older adults with Alzheimer’s dementia---the CATIE-AD trial---was conducted in the community-setting.12 The CATIE-AD study found that the overall effectiveness of antipsychotics was limited, and outweighed by the risks of adverse effects. In 2005, the FDA issued black-box warnings on the atypical antipsychotics for excess stroke and overall mortality risk in older patients with dementia.15 Lastly, a recent Cochrane review of high quality evidence on using atypical antipsychotics to treat patients with dementia (including NH residents) concluded: 1) only risperidone and olanzapine had sufficient data demonstrating efficacy in treating aggression; and 2) no antipsychotic has sufficient data on improving cognitive function.20 Furthermore, “the atypicals should not be used routinely to treat dementia patients unless there is severe distress or risk of physical harm to those living and working with the patient.”

Antipsychotics are also among the most highly regulated medications in NHs and have been so since the 1980s when the Institute of Medicine reported widespread misuse of these agents to sedate and chemically restrain NH residents.21 Today, NHs must maintain careful documentation on the necessity of using antipsychotics for each resident. This includes the reason for the treatment from a list of approved indications, plans for monitoring medication efficacy and tolerability, and future consideration for dose reduction or treatment discontinuation. Failure to do so may result in fines and sanctions on the NH for deficiencies in care. Unfortunately, despite initial reductions in antipsychotic use immediately after the implementation of this federal-level regulatory intervention,10 antipsychotic prescribing remains essentially unchanged in 2007.22

The Challenge is that NHs are Complex Organizations

NHs are complex institutions with a wide variety of organizational models and health care professionals. Medication decisions often represent concerted efforts between the on-site NH staff of nurse practitioners, registered and licensed practical nurses, certified nursing aides, consultant pharmacists and physicians. These physicians are typically off-site and communicate orders by telephone or faxes.23, 24 Social workers often convey family or patient preferences in this process, and consultant pharmacists review the medication order for safety and compliance with regulations. The quality of the medication decision reflects the quality of communication within the NH.25, 26

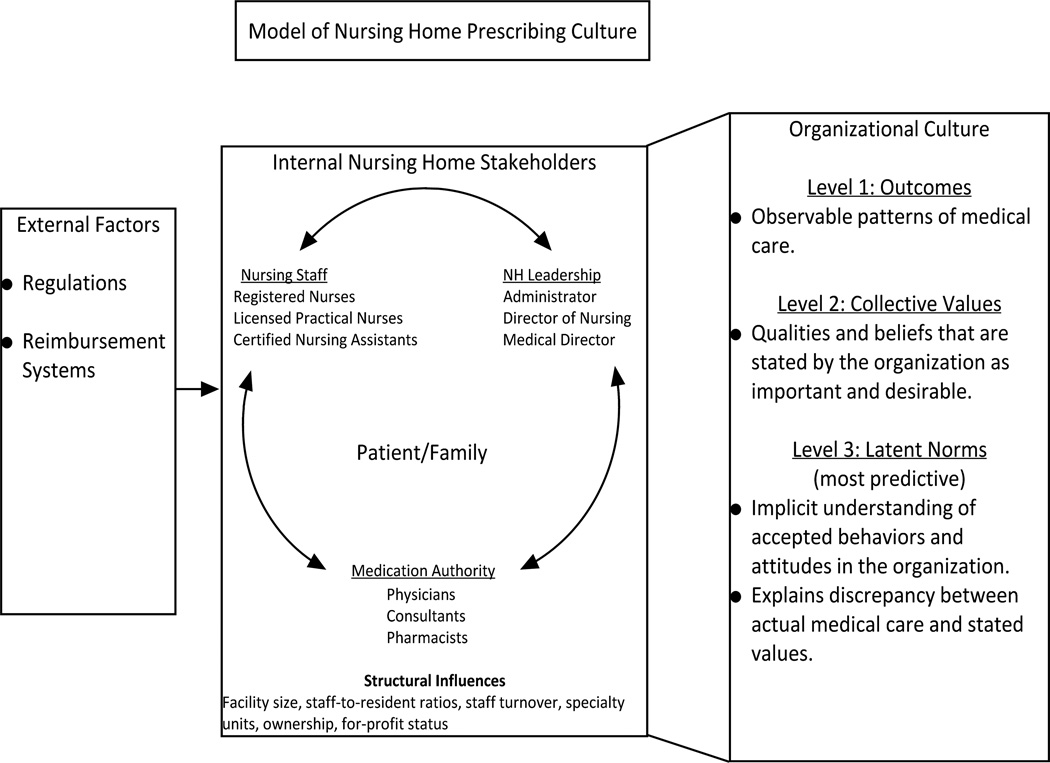

Organizational culture offers a cohesive way for understanding the many influences on prescribing decisions in NHs.27, 28 (Figure 2) Organizational culture is a broad concept that encompasses the shared values, beliefs and assumptions of a group or members working together as a group.29 In this context, each NH may be understood as a micro-society of internal stakeholders who are subject to external pressures and whose inter-related decisions result in observable patterns of medical care.27, 30 For some NHs, high staff turnover31 and many off-site physicians with limited training in NH care may distinguish the culture, while in other NHs a litigious environment may influence medical decisions.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework: Model of Nursing Home Prescribing Culture

Adapted from Hughes, Lapane, Watson, Davies, 2007 [27]

Some of the best examples of how organizational culture affects health care processes and patient outcomes come from the hospital setting. For example, Shortell et al.32 have shown from data collected from 61 US hospitals that quality improvement implementation in the healthcare setting varied by four types of cultures: group culture, based on norms and values of teamwork; developmental culture, based on risk-taking and change; hierarchical culture, based on values associated with bureaucracy; and rational culture, emphasizing efficiency and achievement. Organizational culture type has also shown associations with differences in approaches to quality improvement implementation [e.g. defensive (focusing primarily on meeting external accreditation requirements) or integrative (called ‘prospector’ in their framework, reflecting integration into an overall plan of implementation)]. These differences have predicted variation in patient outcomes. Hospitals with a patient-centered focus have also demonstrated greater investments in change to improve chronic illness care.33

Current research on NHs organizational culture most closely reflects studies regarding the role of patient-centeredness on healthcare outcomes. Also termed “resident-centered care” and “resident-directed care” in the NH literature,34–36 these studies have found that values such as compassion, dignity and respect to be associated with less use of feeding tubes in NH residents with advanced dementia37 and better performance on quality measures such as the number of NH residents having high-risk pressure ulcers, low-risk pressure ulcers, and being bedfast.38

Specific to medications, evidence from a single-site, multi-pronged intervention suggests that antipsychotic use may be reduced by providing combinations of resident-centered activities, prescribing guidelines, and educational rounds to improve NH dementia care.39–43 Furthermore, medication reviews and/or educational interventions alone44–46 do not significantly improve the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing in a pooled analysis.47 Other studies suggest that differences in organizational culture may also explain the wide variation in the use of antipsychotics in NHs that are unexplained by patient case-mix,6, 48 organizational (e.g. profit status) or market characteristics.49 Although the specific drivers of off-label antipsychotic prescribing remain unclear, facility-level factors such as staffing levels,10, 50 nurse beliefs,25 interdisciplinary communication,25, 39, 51 and availability of resident activities40 appear to be associated with variations in antipsychotic use.

Research to Change Prescribing Culture in NHs

Using the framework of organizational culture, we are conducting a cluster-randomized trial to improve the antipsychotic use in NHs using a stepwise approach that begins with an assessment of the prescribing culture of each NH. We have recruited 72 NHs in Connecticut with baseline use of atypical antipsychotics ranging from 2% to 65% of all residents in the facility.

The first step in this study characterizes each NH’s prescribing culture. Specifically, we will conduct a mixed-method study with NH leadership to assess important cultural domains known to be associated with variations in psychotropic medication use. A mixed-method study uses both qualitative and quantitative approaches to characterize observed phenomenon.52 Qualitative components include direct observation of facility characteristics using the Observable Indicators of Nursing Home Care Quality Instrument53 and semi-structured interviews with NH leadership. Questionnaires for leadership, direct care staff, nurses, prescribers, and associated consultant pharmacists based on validated NH culture change tools.34 Summarized in a 2006 CMS report Measuring Culture Change, six constructs were identified in the definition of culture change: resident-directed care and activities; home environment; relationships with staff, family, resident and community; staff empowerment; collaborative and decentralized management; and measurement-based continuous quality improvement processes.34 Sample questions based on these domains, and others described in related resident-centered assessments,25, 54 are specified in Table 1, and include assessments of NH structure (e.g. presence of a special care dementia unit and home-like atmosphere), decision-making process (e.g. protocols for the management of residents with behavioral issues), staffing (e.g. consistent assignment and staff turnover), interdisciplinary collaboration (e.g. inclusion of direct care staff, geriatric psychiatry in behavior management plans), and resident-centered communication (e.g. resident activities and family involvement).

Table 1.

Example of Qualitative Interview Domains and Sample Questions for Nursing Home Leadership

| Nursing Home Culture Domain |

Proposed Questions |

|---|---|

| Home/physical environment | Does your facility have a special dementia unit? |

| If so, please describe. | |

| Does your facility have a home-like environment introducing plants, pets, children and surroundings that are reminiscent of past lives? | |

| Resident-directed care and activities | How many hours of activities are available to residents with dementia each day? |

| Decision-making processes | Is there a protocol for direct care staff to respond to patients who exhibit challenging behaviors? |

| Imagine that a patient at your facility begins to display behavior problems. This patient begins to become loud, shouting or swearing at staff and other residents. He or she starts to throw things occasionally, and struggles when staff try to help dress, bathe or feed him or her. Imagine this has been going on for about a week, and seems to be getting worse rather than better. | |

| How would staff in your facility respond? | |

| Would there be an interdisciplinary team meeting to develop a management plan? Who would attend the meeting? | |

| Who would develop (write) the behavior management plan? | |

| Staffing | Does your facility aim for consistency of CNA and nurse staffing for difficult patients on each shift? |

| Staff training | Is there behavior management training beyond the 8 hours of required training about dementia care for direct care staff? |

| Staff empowerment | Describe the process to develop a behavior management plan? [Is it interdisciplinary? Who is involved? |

| Relationships with staff, family, resident and community | At what point is the family contacted? |

If an antipsychotic medication is initiated, is informed consent required?

| |

| Readiness to change | What would it take for your facility to implement a program to improve antipsychotic prescribing? |

| Under what circumstances would your facility put additional resources for staff training and time to improve behavioral management and improve understanding of antipsychotic risks? | |

| Dissemination and Communication | What forms of materials would be helpful for you to communicate with families about behavior management and antipsychotic use? |

| What forms of materials would be helpful for you to communicate with direct care staff and prescribers about behavior management and antipsychotic use? |

The goal for the assessments is twofold. First, these assessments will guide the development of tailored educational and interventional approaches to improve antipsychotic prescribing by incorporating the perspectives of multiple stakeholders, and will depend on tailoring the intervention to the NH’s culture. Potential products for targeted stakeholders are described in Table 2. Second, these assessments will contribute to the development of instruments to characterize a NH’s medication prescribing culture as 'resident-centered’ or more ‘traditional’, validated with actual facility-level antipsychotic use, change in antipsychotic use after the intervention, and direct observation of each NH’s facilities’ structure and process of medication decision-making. We expect to find that some NHs will have hierarchical, traditional cultures with defensive approaches to quality improvement implementation, while others will have group, resident-centered cultures with integration of team-level interventions with physicians educated in partnership with nurses. Other facilities may have strong medical director models where the most effective interventions will require a centralized coordination of efforts through the medical director. Improving prescribing in NHs must incorporate the perspectives of multiple stakeholders and their particular NH’s culture.

Table 2.

Potential Intervention Products

| Stakeholder Group |

Rationale/ justification of target/unmet need |

Potential Product |

|---|---|---|

| NH Leadership (administrator, Director of Nursing, medical director) | Responsible for setting policy and quality standards, NH leadership can initiate culture change within facilities.40 | Proposed Adaptation: Summary of atypical antipsychotic risks, pricing, and summary of Nursing Home Reform Act regulations from the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987. |

| Proposed Use: Mass mailing to inform NH leadership about antipsychotic risks, and informing NHs the existence of an online interactive toolkit about antipsychotics for NH staff development. | ||

| Prescribers (physicians and nurse practitioners) | Prescribers are assumed to know the risk and benefits of the off-label use antipsychotic use, but level of knowledge is unclear. | Proposed Adaptation: Informational summary, including interactive module available on website accompanied by a mass fax to prescribers with basic information summarizing risk of atypical antipsychotics, off-label use, side effects, a summary of the CATIE-AD study findings7, dose and pricing. |

| Proposed Use: Mass mailing to inform prescribers about risks, presence of AHRQ toolkit in NH, existence of an online interactive module with continuing medical education (CME) credit | ||

| Consultant Pharmacists | Mandated by CMS to prompt therapeutic interchange or dose reduction by prescribers; pharmacists may be the best point of contact with physicians who prescribe antipsychotics. | Proposed Adaptation: Review form addressed by consultant pharmacists to prescribers to confirm monitoring of QTc interval, off-label use for behavioral management, and acknowledgement of risk of death and stroke in each patient receiving atypical antipsychotics. |

| Proposed use: A brief, AHRQ CERSG-adapted form could be used by pharmacists during CMS-mandated monthly reviews to inform and prompt prescribers to initiate dose reduction trials. | ||

| Nursing Staff (registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, certified nurse assistants) | In response to challenging resident behavior management situations, nursing staff can precipitate the chain of prescribing by initiating requests for antipsychotics to prescribers. | Proposed Adaptation: |

| Educational program on atypical antipsychotics stressing increased risk of death and federal regulations about antipsychotic use. | ||

| Educational program on fundamentals of behavior management. | ||

| Both educational programs will be enhanced PowerPoint presentations, with embedded video and audio. | ||

| Proposed use: Program to be used in monthly staff education programs with continuing nurse education credits. | ||

| Residents and Families | In some NH residents or family members are informed and may be asked to sign off on use of antipsychotics. | Proposed Adaptation: Form that can be included in residents’ medical records recording presentation of information about antipsychotic medications to resident or family members upon prescribing. |

| Proposed use: Form can be used to guide communication and track information given to residents and family members. |

Summary

Approximately 56 percent of NHs have either adopted culture change or are committed to culture change adoption.38 Emerging research on the role of organizational culture in NHs and its role in quality of care show promise. While different types of NH culture and organizational approaches to care currently exist--such as the Eden Alternative, Evergreen, and Green Houses,55 --further work can elucidate which elements of these models map to important cultural elements that contribute to improved pharmaceutical care. The Veterans Affairs Geriatric and Extended Care Program that oversee the 133 nursing homes (now called community living centers) nationwide have been leaders in implementing culture transformation. In fact they have each of the NH facilities self-report on a website twice yearly their scores in the six categories that make up the Artifact of Culture Change Tool, and are currently working on projects in influence change and determine their effectiveness.56 It remains unclear whether marrying elements of prescribing intervention trials46 with the broader strategy of the NH culture change movement will lead to meaningful reductions in inappropriate antipsychotic use, increases in the implementation of federally-mandated tapers of currently prescribed antipsychotics, and increased resident-centered care. We hypothesize that a combined interventional approach that educates NH leadership and prescribers, addresses organizational behavior, and improves interdisciplinary communication and direct care staff involvement can achieve sustained improvements in prescribing. We need a better understanding of the various ways patient-level prescribing decisions, and facility-level quality improvement decisions, are made in NHs so we can effectively intervene to finally align the use of medications such as antipsychotics with the evidence-base.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This project was supported by R18 HS019351from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Dr. Tjia was supported by R21 HS19579 from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Dr. Briesacher was supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Award (K01AG031836) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avorn J, Gurwitz JH. Drug use in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:195–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-3-199508010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doshi JA, Shaffer T, Briesacher BA. National estimates of medication use in nursing homes: findings from the 1997 medicare current beneficiary survey and the 1996 medical expenditure survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magaziner J, German P, Zimmerman SI, et al. The prevalence of dementia in a statewide sample of new nursing home admissions aged 65 and older: diagnosis by expert panel. Epidemiology of Dementia in Nursing Homes Research Group. Gerontologist. 2000;40:663–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Judge J, et al. The incidence of adverse drug events in two large academic long-term care facilities. Am J Med. 2005;118:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med. 2000;109:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach ('academic detailing') to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2. CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey D, et al. ACNP White Paper: update on use of antipsychotic drugs in elderly persons with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:957–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner AK, Chan KA, Dashevsky I, et al. FDA drug prescribing warnings: is the black box half empty or half full? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:369–386. doi: 10.1002/pds.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shorr RI, Fought RL, Ray WA. Changes in antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes during implementation of the OBRA-87 regulations. JAMA. 1994;271:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PE, Gill SS, Freedman M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38125.465579.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934–1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff. 2009;28:w770–w781. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory April 2005: Death with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. [Accessed January 25, 2011]; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/UCM053171.

- 16.Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, et al. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:89–95. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathematica Policy Research Institute. Chartbook: Medicaid Pharmacy Benefit Use and Reimbursement in 2006. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2010. Exhibit 21. Total Annual Medicaid reimbursement for top 10 drug groups among dual beneficiaries, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.IMS Health. [Accessed July 11, 2011];2007 Top Therapeutic Classes by U.S. Sales. 2008 Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Document/TopLine%20Industry%20Data/2007%20Top%20Therapeutic%20Classes%20by%20Sales.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballard C, Wait J, Birks J. Atypical antipsychotics for aggression and psychoses in Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine: Committee on Nursing Home Regulation. Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagnado L. Nursing homes struggle to kick drug habit: New therapies sought for dementia sufferers; Music and massages. Wall Street Journal. 2007;A1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitson HE, Hastings SN, Lekan DA, et al. A quality improvement program to enhance after-hours telephone communication between nurses and physicians in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1080–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perkins A, Gagnon R, deGruy F. A comparison of after-hours telephone calls concerning ambulatory and nursing home patients. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svarstad BL, Mount JK, Bigelow W. Variations in the treatment culture of nursing homes and responses to regulations to reduce drug use. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:666–672. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tjia J, Mazor KM, Field T, et al. Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2009;5:145–152. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes CM, Lapane K, Watson MC, et al. Does organisational culture influence prescribing in care homes for older people? A new direction for research. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:81–93. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruneir A, Lapane KL. It is time to assess the role of organizational culture in nursing home prescribing patterns. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:238–239. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.43. author reply 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies HT, Nutley SM, Mannion R. Organisational culture and quality of health care. Qual Health Care. 2000;9:111–119. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damestoy N, Collin J, Lalande R. Prescribing psychotropic medication for elderly patients: some physicians' perspectives. CMAJ. 1999;161:143–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care. 2005;43:616–626. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163661.67170.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shortell SM, O'Brien JL, Carman JM, et al. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept versus implementation. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:377–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42:1040–1048. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colorado Foundation for Medical Care. Measuring Culture Change: Literature Review: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 25, 2011];2006 (online). Available at: http://www.cfmc.org/files/nh/MCC%20Lit%20Review.pdf.

- 35.Grant L. Culture Change in a For-Profit Nursing Home Chain: An Evaluation. [Accessed July 11, 2011];The Commonwealth Fund. 2008 (online). Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/Grant_culturechangefor-profitnursinghome_1099.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doty MM, Koren MJ, Sturla EL. Culture change in nursing homes: how far have we come? Findings from The Commonwealth Fund 2007 National Survey of Nursing Homes. The Commonwealth Fund. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, et al. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:83–88. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Health Care Association. 2010 Annual Quality Report: A Comprehensive Report on the Quality of Care in America's Nursing and Rehabilitation Facilities. [Accessed January 25, 2011]; (online). Available at: http://www.ahcancal.org/quality_improvement/Documents/2010QualityReport.pdf.

- 39.King MA, Roberts MS. Multidisciplinary case conference reviews: improving outcomes for nursing home residents, carers and health professionals. Pharm World Sci. 2001;23:41–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1011215008000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rovner BW, Steele CD, Shmuely Y, et al. A randomized trial of dementia care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E, et al. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;332:756–761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38782.575868.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt I, Claesson CB, Westerholm B, et al. The impact of regular multidisciplinary team interventions on psychotropic prescribing in Swedish nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcum ZA, Handler SM, Wright R, et al. Interventions to improve suboptimal prescribing in nursing homes: A narrative review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:183–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avorn J, Soumerai SB, Everitt DE, et al. A randomized trial of a program to reduce the use of psychoactive drugs in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:168–173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207163270306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, et al. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004;33:612–617. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:257–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishtala PS, McLachlan AJ, Bell JS, et al. Psychotropic prescribing in long-term care facilities: impact of medication reviews and educational interventions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:621–632. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817c6abe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Bronskill SE, et al. Variation in nursing home antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:676–683. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castle NG, Hanlon JT, Handler SM. Results of a longitudinal analysis of national data to examine relationships between organizational and market characteristics and changes in antipsychotic prescribing in US nursing homes from 1996 through 2006. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Svarstad BL, Mount JK. Nursing home resources and tranquilizer use among the institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:869–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt IK, Svarstad BL. Nurse-physician communication and quality of drug use in Swedish nursing homes. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1767–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rantz MJ, Aud MA, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, et al. Field testing, refinement, and psychometric evaluation of a new measure of quality of care for assisted living. J Nurs Meas. 2008;16:16–30. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.16.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White DL, Newton-Curtis L, Lyons KS. Development and initial testing of a measure of person-directed care. Gerontologist. 2008;48:114–123. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010;29:312–317. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Personal communication Christa M. Hojlo, PhD, RN, NHA Director VA Nursing Home Care Director State Veterans Home Clinical and Survey Oversight 810 Vermont Avenue, NW (114) Washington, DC 20420.