Abstract

Significance: Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), produced by the desulfuration of cysteine or homocysteine, functions as a signaling molecule in an array of physiological processes including regulation of vascular tone, the cellular stress response, apoptosis, and inflammation. Recent Advances: The low steady-state levels of H2S in mammalian cells have been recently shown to reflect a balance between its synthesis and its clearance. The subversion of enzymes in the cytoplasmic trans-sulfuration pathway for producing H2S from cysteine and/or homocysteine versus producing cysteine from homocysteine, presents an interesting regulatory problem. Critical Issues: It is not known under what conditions the enzymes operate in the canonical trans-sulfuration pathway and how their specificity is switched to catalyze the alternative H2S-producing reactions. Similarly, it is not known if and whether the mitochondrial enzymes, which oxidize sulfide and persulfide (or sulfane sulfur), are regulated to increase or decrease H2S or sulfane-sulfur pools. Future Directions: In this review, we focus on the enzymology of H2S homeostasis and discuss H2S-based signaling via persulfidation and thionitrous acid. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 770–782.

Hydrogen Sulfide Biogenesis

In mammals, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is primarily produced by enzymes of the trans-sulfuration pathway, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) (11, 34, 71) (Fig. 1). A third enzyme, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (MST) can also contribute to endogenous H2S production in the presence of reductants using 3-mercaptopyruvate as a substrate (47, 67). Despite the high level of interest in the physiological effects of H2S, the regulation of its biogenesis is poorly understood.

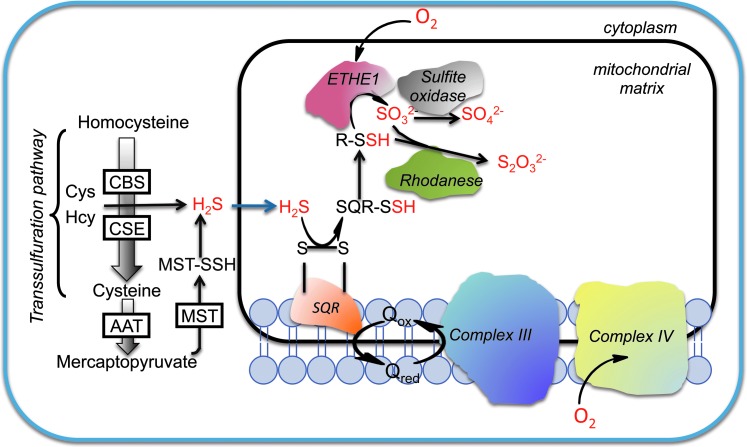

FIG. 1.

Pathways for H2S production and oxidation. H2S biogenesis catalyzed by the trans-sulfuration pathway enzymes, CBS and CSE occurs in the cytoplasm. The AAT/MST pathway exists in the cytoplasm and in the mitochondrion. Sulfide is oxidized in the mitochondrion by SQR to generate persulfide. In the second step, the persulfide is oxidized by ETHE1, a dioxygenase, to generate sulfite that can either be oxidized by rhodanese or by sulfite oxidase. Electrons released in the SQR reaction are captured by ubiquinone and transferred to the electron transport chain at the level of complex III. AAT, aspartate aminotransferase; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; CSE, cystathionine γ-lyase (γ-cystathionase); ETHE1, sulfur or persulfide dioxygenase; SQR, sulfide quinone oxidoreductase; H2S, hydrogen sulfide. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

In addition to H2S generation, the trans-sulfuration pathway enzymes are responsible for the synthesis of cysteine from homocysteine. The intracellular concentration of cysteine varies from 90 to 100 μM in most tissues (85) but is higher in the kidney (∼1 mM) (74). Cysteine has multiple metabolic fates and in addition to H2S biogenesis, can be directed to the synthesis of glutathione and taurine whose steady-state concentrations can reach up to 10 and 20 mM, respectively (84–86). In contrast, the steady-state concentration of H2S is estimated to be in the low nanomolar range in most tissues (17, 87) with the exception of aorta, where it is ∼20- to 100-fold higher (41). Recent kinetic studies have indicated that the flux of sulfur into H2S is high and comparable to that directed into the glutathione pathway in liver (87). Hence, the low steady-state concentration of H2S reflects a high rate of clearance and/or consumption (87).

It is estimated that ∼50% of the cysteine used for hepatic glutathione synthesis is derived from methionine via the trans-sulfuration pathway (4, 50). Genetic deficiency of CBS, the first enzyme in the trans-sulfuration pathway, causes homocystinuria characterized by multisystem complications involving the cardiovascular, neuronal, central nervous, and ocular systems (51). Further, connective tissue disorders in these patients are attributed to cysteine deficiency indicating the importance of the trans-sulfuration pathway in supplying cells with cysteine (42). Hence, understanding how allocation of cysteine and homocysteine into alternative metabolic pathways is gated is essential for understanding how cysteine is apportioned to meet intracellular needs. In particular, since the canonical trans-sulfuration pathway uses homocysteine and serine to generate cysteine, it is particularly important to understand how the same catalysts are subverted to generate H2S from cysteine and homocysteine and under what circumstances. Regulation of H2S generation is expected to be one mechanism for augmenting or diminishing its levels on demand. In the following section, the enzymology of H2S generation by CBS, CSE, and MST is discussed.

H2S generation by CBS

CBS catalyzes the first and committing step in the trans-sulfuration pathway, that is, the β-replacement of serine with homocysteine to form cystathionine and water. When cysteine replaces serine as a substrate, the reaction products are cystathionine and H2S instead. CBS also catalyzes additional reactions that produce H2S from cysteine (Fig. 2), that is, β-replacement of cysteine by water to form serine and β-replacement of cysteine by a second mole of cysteine to produce lanthionine. In both these reactions, H2S is eliminated. Of these, the β-replacement of cysteine with homocysteine is kinetically the most efficient H2S-producing reaction (71). Serine (560 μM) is more abundant inside the cell than cysteine and human CBS exhibits a lower KM for serine (2 mM) than for cysteine (6.8 mM) (71, 77). Hence, serine is expected to be the substrate of choice for CBS. It is not known if and how the substrate preference for CBS can be switched from serine to cysteine to promote its involvement in the trans-sulfuration pathway versus in H2S generation.

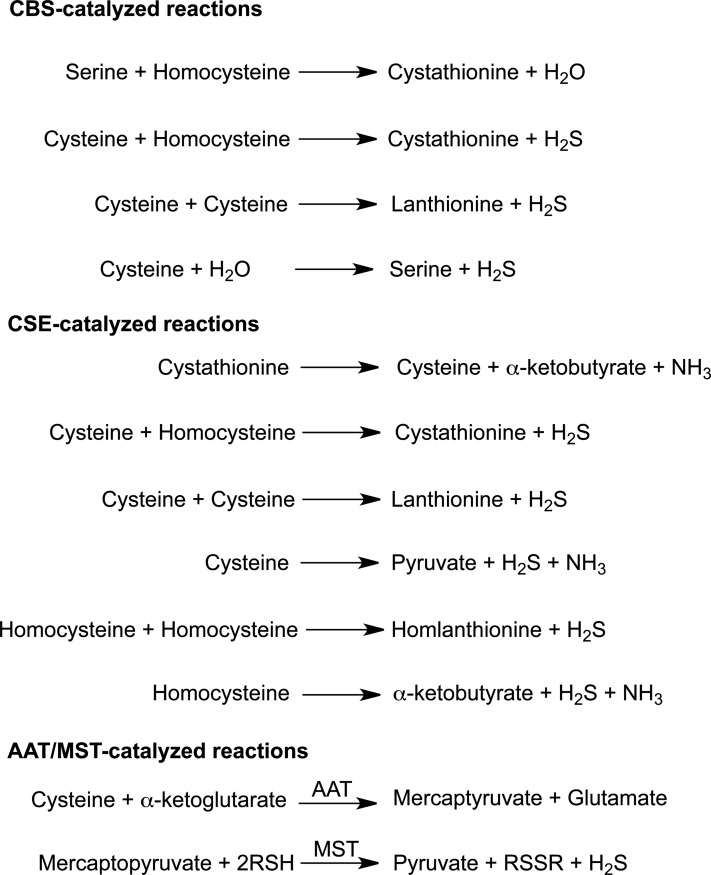

FIG. 2.

H2S-generating reactions catalyzed by CBS, CSE, and AAT/MST. The trans-sulfuration enzymes, CBS and CSE catalyze multiple H2S-generating reactions. The canonical reaction catalyzed by each enzyme in the trans-sulfuration pathway is shown at the top of the respective group. The AAT/MST pathway involves an initial transamination reaction followed by a sulfur transferase reaction. MST, mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferases.

The activity of CBS appears to be highly regulated. Unlike other known pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes, CBS contains a regulatory heme cofactor (Fig. 3a) that functions as a redox-dependent gas sensor (35, 63, 76, 78). The heme in CBS exists in two oxidation states: ferric (Fe+3) and ferrous (Fe+2). Ferrous CBS can bind the gas signaling molecules, CO and NO, resulting in inhibition of its catalytic activity (76, 78). Air oxidation of the ferrous-CO or ferrous-NO forms of CBS leads to recovery of the ferric heme state and of enzyme activity (Fig. 4).

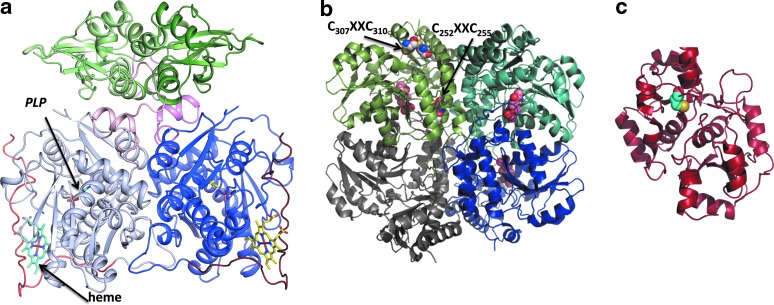

FIG. 3.

Structures of H2S-producing enzymes. (a) The structure of full-length dimeric Drosophila CBS showing the lower catalytic domains containing PLP and heme and the upper regulatory subunits (PDB file 3PC4). The heme and PLP shown in stick representation, bind to the catalytic domains while SAM binds to the regulatory domain. (b) Structure of homotetrameric human CSE in which the subunits are shown in different shades (PDB file 2NMP). PLP is seen in three of the four subunits and is shown in ball representation. The two CXXC motifs are shown in sphere representation in one of the subunits. (c) Structure of human MST (PDB file 3OLH). The active site cysteine (Cys248) that is modified as a persulfide is shown in sphere representation. SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; PLP, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

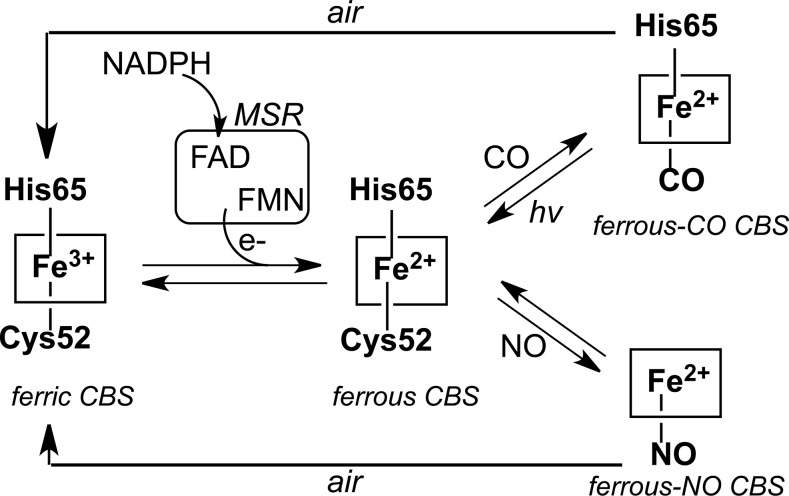

FIG. 4.

Redox-dependent regulation of human CBS by gases. Ferric CBS can be reduced by NADPH in the presence of the diflavin methionine synthase reductase to give ferrous CBS. The latter can react with CO or NO to give ferrous-CO or ferrous-NO CBS, respectively, which upon air oxidation revert to ferric CBS. The NO- and CO-liganded forms of CBS are inactive.

The relatively low potential of the Fe+3/Fe+2 redox couple for the heme (−350±4 mV) in CBS (70) begs the question as to whether redox modulation of CBS has physiological relevance. In this context, the recent demonstration that CBS can be reduced by a cytoplasmic diflavin oxidoreductase like methionine synthase reductase is important (35). In the presence of CO and methionine synthase reductase, the inhibitory ferrous-CO CBS species is formed showing that this mode of redox regulation is physiologically accessible. Further, modulation of CBS activity by NO or CO provides a mechanism for crosstalk between these gas signaling systems. A physiologically important context for CO regulation is the regulation of cerebral blood flow under normoxic versus hypoxic conditions, a protective mechanism to maintain adequate supply of oxygen to brain, which is reportedly mediated by modulation of H2S production of CBS by CO (49).

CBS is allosterically activated by S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), a universal methyl group donor involved in numerous methylation reactions (16), which binds to the C-terminal regulatory domain of the protein (Fig. 3a). SAM plays a central role in sulfur metabolism by mobilizing the methyl group of methionine and making the sulfur containing amino acid homocysteine, available for recycling via transmethylation or for trans-sulfuration. By also regulating CBS, SAM plays a critical role in coordinating regulation of methylation and redox homeostasis. SAM enhances β-replacement by homocysteine of both serine and cysteine (71). In addition to functioning as an allosteric activator, SAM also stabilizes CBS (62). Under pathological conditions where SAM levels are depressed, destabilization of CBS serves as a mechanism for redirecting sulfur metabolic flux toward methionine conservation.

Another mode of regulation of CBS is by post-translational modification by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein, which is correlated with the localization of CBS in the nucleus (1, 36). Sumoylation of CBS is sensitive to the concentration of its substrates and leads to diminished catalytic activity (1). However, the mechanism by which sumoylation affects CBS activity and whether this regulatory strategy is pertinent to H2S production are not known.

The trans-sulfuration pathway is regulated in response to various triggers such as hormones and conditions that lead to elevated cyclic AMP levels (19). Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats exhibit increased hepatic CBS expression and activity, which was also seen in glucocorticoid-stimulated rat hepatoma cells (65). Insulin treatment reduced CBS expression in both the streptozotocin rat model and in glucocorticoid-treated cells. In mouse kidney, CBS is regulated by testosterone and males exhibit ∼threefold higher CBS activity than females, which is correlated with a similar difference in CBS protein levels (88). Interestingly, a range of regulatory patterns for renal CBS is seen in mammals: females exhibit higher CBS activity in humans and rats but lower activity in mice, while gender-specific differences are not seen in rabbit, hamster, and guinea pig (88). In the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP, testosterone downregulates CBS via a post-transcriptional mechanism and results in lower flux through the trans-sulfuration pathway and lower glutathione levels (61). CBS is also post-translationally activated in response to oxidative stress, resulting in ∼twofold increase in flux through the trans-sulfuration pathway (50). However, the molecular mechanism of this upregulation and its pertinence to H2S generation are not yet known.

H2S generation by CSE

The canonical role of CSE in the trans-sulfuration pathway is to cleave cystathionine forming cysteine, ammonia, and α-ketobutyrate. CSE is a homotetrameric enzyme (Fig. 3b) and can catalyze various other reactions to generate H2S from cysteine (Fig. 2). Unlike CBS, homocysteine alone serves as an H2S-generating substrate for CSE. The relaxed substrate specificity of CSE allows accommodation of cystathionine, cysteine, and homocysteine in the same binding pocket where they compete for forming a Schiff base with PLP. In contrast, homocysteine does not bind to the PLP site in CBS. Consistent with this observation, H2S production by CSE but not CBS is sensitive to homocysteine concentrations (71). Hence, with increasing concentrations of homocysteine, as seen in homocystinuric patients, the contribution of this substrate to H2S formation is predicted to increase progressively (71).

CSE is believed to be the major endogenous source of H2S in peripheral tissues as CSE knockout mice have low serum H2S levels (95). In brain, CSE levels are relatively low, at least in mice and CBS is believed to be the primary producer of H2S (13, 89). Brain H2S levels were essentially unchanged in CSE knockout mice (95). However, a commonly overlooked factor that could potentially lead to underestimation of the contribution of CBS is that it produces H2S preferentially from homocysteine+cysteine, whereas the preferred route for H2S production by CSE requires only cysteine (71). Since cysteine is employed as the sole substrate in most assays with cell and tissue extracts, the full contribution of CBS is missed. Hence, the significance of CBS in H2S production in peripheral tissues is routinely underestimated and requires further investigation.

An additional reason why the contribution of CBS to H2S production might have been underestimated in CSE knockout mice is the following. CSE is required for cysteine synthesis via the trans-sulfuration pathway and disruption of its gene also deprives CBS of one of the substrates needed for H2S production. Hence, both CSE and CBS-dependent H2S production is affected by disruption of the CSE gene. In contrast, disruption of the CBS gene leads to accumulation of homocysteine, a substrate for H2S production by CSE (11). Given the complexity and the multitude of H2S-generating reactions catalyzed by CBS and CSE (Fig. 2), special attention must be paid to the assay design and data interpretation. Specifically, it is important to assess H2S generation in the presence of cysteine versus cysteine+homocysteine to more fully estimate the contributions of both enzymes.

Regulation of CSE is not well understood. Human CSE is a tetramer with a subunit molecular mass of 45 kDa. Each subunit contains two CXXC motifs (Fig. 3b) and their ability to influence CSE activity in a redox-sensitive manner is not known. Under in vitro conditions, CSE is post-translationally modified by SUMO (1), a signal that is often used for nuclear localization. The physiological relevance and the role, if any, of sumoylation on CSE function is currently unknown. A twofold increase in CSE activity by calmodulin, albeit in the presence of high calcium concentration (2 mM), has been reported (95). Our laboratory has not been able to detect calmodulin-dependent activation of purified recombinant human CSE and calmodulin from various sources (Padovani and Banerjee, unpublished results). The relevance of calcium/calmodulin-dependent regulation of CSE remains open.

CSE expression is upregulated in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in a mechanism dependent on the activating transcription factor, ATF4 (14). The latter is expressed as part of the unfolded protein response to alleviate stress damage (90). The upregulation of CSE correlates well with the ∼fourfold increase in H2S production in response to ER stress where H2S plays a protective role. H2S increases phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), an ER kinase, by persulfide modification and inactivation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTP1B (40). Activated PERK leads to inhibition of general protein synthesis by phosphorylating eukaryotic initiation factor 2α, a common protective cellular response to stress (22). CSE expression is increased in liver and pancreas in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, a model for type-1 diabetes (30, 97). Insulin treatment reduced CSE expression (97). CSE is also overexpressed in pancreatic β-cells in Zucker diabetic fatty rats, a model for type-2 diabetes. Addition of the NaHS or cysteine reportedly inhibited insulin release from islets and from the MIN6 pancreatic β-cells (37) while H2S production was higher in islets isolated from Zucker diabetic fatty versus Zucker lean rats (93). On the other hand, CSE expression is reduced in kidney proximal tubules in a spontaneous diabetic mouse model (94). CSE expression is upregulated in response to inflammation by TNFα−dependent recruitment of the transcription factor specificity protein 1 (SP1) (66), which binds to the CSE promoter (28).

H2S generation by MST

MST can produce H2S from 3-mercaptopyruvate (67), which is formed by a transamination reaction between cysteine and α-ketoglutarate catalyzed by aspartate aminotransferase (AAT)/cysteine aminotransferase (83) (Fig. 2). MST uses 3-mercaptopyruvate as a substrate and transfers the sulfur to a nucleophilic cysteine in the active site (Fig. 3c) yielding persulfide and pyruvate (Fig. 1). The MST-bound persulfide is a potential source of H2S in the presence of a reductant or following transfer to an acceptor such as thioredoxin (91) and subsequent reduction.

The KM values for mercaptopyruvate for rat and bovine MST are 1.2 mM (57) and 2.8 mM (31), respectively. The activity of MST in cysteine degradation and hence in H2S production, is gated by transamination of cysteine, which is a side activity of AAT. While the KM for aspartate is 1.6 mM, the KM for cysteine is 22 mM, which is significantly higher (2, 91). Further, aspartate is a potent inhibitor of cysteine transamination by AAT (2). While the cellular concentration of cysteine in most tissues is low (∼30–100 μM) (74), the concentration of aspartate is relatively high, ∼730 μM and 4 mM in mouse liver and brain respectively (Vitvitsky, V. and Banerjee R, unpublished data). The mitochondrial cysteine concentration in rat is reported to be ∼0.7–1 mM (82). These numbers would seem to argue against significant diversion of cysteine to H2S production via the AAT/MST pathway in the cytosol under most conditions. However, the contribution of the mitochondrial MST pool to H2S production might be more significant. The AAT/MST route might also be more significant for H2S generation in tissues where the cysteine concentration is high, for example, kidney where cysteine is ∼1 mM (74), or in tissues with low CBS and/or CSE expression. MST is expressed in kidney, liver, aorta, and in brain (55). MST is proposed to contribute to H2S production in brain (68) and in vascular endothelial tissues (67). Unlike CBS and CSE, MST is localized in the mitochondrion in addition to the cytoplasm (55, 75), where it might contribute to energy metabolism via the sulfide oxidation pathway.

The active site of MST has a reactive cysteine residue that is sensitive to oxidants and represents a switching mechanism for redox regulation. However, unlike the trans-sulfuration pathway, MST is inhibited under oxidative stress conditions. At stoichiometric concentrations of H2O2, the active site cysteine is converted to cysteine sulfenate with concomitant enzyme inactivation that is reversed by DTT or by a thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system (56). The rationale for inhibition of MST under oxidative stress conditions is that it conserves cysteine needed for glutathione synthesis. However, for this regulation to be a plausible strategy for sparing cysteine, AAT, the enzyme, which utilizes cysteine to generate the substrate for MST, mercaptopyruvate, needs to be inhibited. While modification of a reactive cysteine residue in AAT reduced the activity of cytoplasmic AAT (5), no change in the activity of mitochondrial AAT was observed (18). Deletion of the AAT1 gene in yeast causes a respiratory defect and impaired iron homoeostasis with no apparent change in sensitivity to oxidative stress (72). Rat MST also undergoes redox-dependent dimerization mediated by intersubunit disulfide linkage, which is accompanied by inhibition. The latter is reversed by thioredoxin-dependent reduction (58). However, this mechanism of redox regulation is not likely to be pertinent for human MST since the cysteine residues involved in subunit cross-linking in rat MST are not conserved in the human enzyme.

Catabolism of H2S

Sulfide administered at sublethal concentrations is rapidly oxidized in mammals and primarily excreted as thiosulfate and sulfate (12). Metabolic labeling studies with Na235S have indicated tissue-specific differences in sulfide catabolism rates and in product distribution (3). Rat liver converts sulfide primarily to sulfate, kidney to a mixture of thiosulfate and sulfate, and lung predominantly to thiosulfate. The sulfide oxidation pathway resides in the mitochondrion and oxidation of thiosulfate to sulfate was shown to be glutathione-dependent. These early labeling studies established thiosulfate and sulfite as intermediates in the sulfide oxidation pathway leading to sulfate (3, 12, 39). Coupling of sulfide catabolism to oxidative phosphorylation via ubiquinone, makes sulfide the first known inorganic substrate for the human electron transfer chain (20). In this section, the enzymology of H2S and persulfide oxidation catalyzed by sulfide quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) and persulfide dioxgenase (ETHE1), respectively, is discussed.

H2S oxidation by SQR

SQR gates the entry of H2S into the oxidation pathway (Fig. 1). SQR belongs to the family of disulfide oxidoreductases and is found in all three domains of life (79). It is characterized by high substrate affinity and reaction rates. It is an enzyme with ancient origins and the extant eukaryotic SQRs are traced to an eubacterial donor from which the common ancestor of fungi and animals acquired this gene (79). SQRs are membrane proteins found on the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane in bacteria and in the inner mitochondrial membrane in eukaryotes. They are monotopic proteins that might be dimeric or trimeric in the membrane and harbor a single flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor in each monomer (Fig. 5a). The crystal structures of several SQRs have been reported (7, 9, 10, 43) and are characteristic of proteins in the flavin disulfide reductase family. The structure comprises a C-terminal domain with two amphipathic helices considered to be important for membrane binding and two Rossman fold domains, with the N-terminal one binding the FAD cofactor. SQRs have a high catalytic turnover rate and low micromolar KM for sulfide (7, 9, 10).

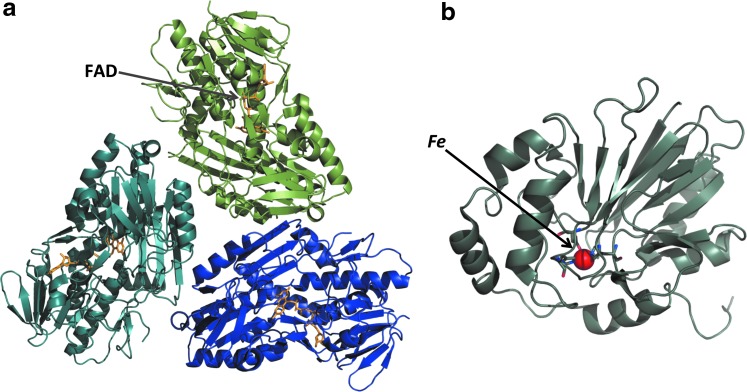

FIG. 5.

Structures of enzymes in the sulfide oxidation pathway. Structures of (a) SQR from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus (PDB file: 3HYW) and (b) Arabidopsis ETHE1 (PDB file:2GCU) showing the mononuclear nonheme iron (sphere) in the active site. The three subunits of SQR are shown in different shades and the FAD is shown in stick representation in (a). FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

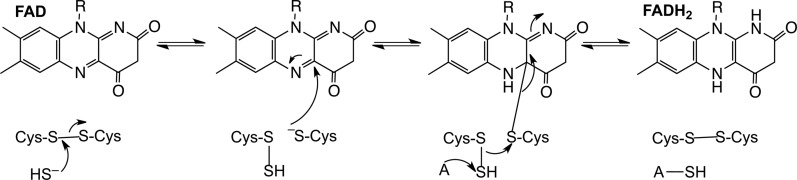

The FAD cofactor in SQRs can either be noncovalently bound to the active site (10, 29) or covalently bound via a thioether linkage between an active cysteine or a persulfide and the 8-methylene group of the isoalloxazine ring (7, 43). The FAD alternates between accepting electrons from sulfide and donating them to ubiquinone, positioned proximal to the isoalloxazine ring. Like other flavoprotein disulfide reductases, SQR harbors a redox-active dithiol/di-sulfide pair on the re face of the flavin cofactor. A minimal reaction mechanism begins with the attack of sulfide on an active site disulfide forming a persulfide and liberating a cysteine thiolate (Fig. 4). The latter attacks the FAD forming a C4A adduct. Nucleophilic attack of an acceptor on the sulfane sulfur atom sets up re-formation of a disulfide and a two-electron transfer to the FAD to give FADH2. Electrons from FADH2 are transferred to ubiquinone that is positioned on the si side of the isoalloxazine ring and is bound in a surface-exposed channel (10).

In bacterial SQR's, product release does not precede binding of each mole of sulfide to the active site. Instead, the catalytic cycle repeats until the maximum length of the polysulfide that can be accommodated in the sulfide oxidation pocket is achieved. Two consecutive nucleophilic attacks by sulfide restore the original disulfide state of the enzyme and the release of the polysulfide product. The crystal structure of the Acidianus ambivalens SQR reveals a trisulfide bridge between the two active site cysteines while the Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans protein has been crystallized with a branched bridge containing five sulfur atoms between the two cysteines (7, 10). Linear and cyclic polysulfur intermediates of variable length were seen in the structure of the Aquifex aeolicus SQR (43). Spatial constraints within the active site limit the length of the polysulfide chain, and in bacterial SQRs, the oxidized sulfur is released as a soluble polysulfide containing up to ten sulfur atoms (10, 21). In contrast, in mammalian SQR, the persulfide is transferred to an acceptor at the end of each catalytic cycle (Fig. 6) (25).

FIG. 6.

Minimal mechanism for the reaction catalyzed by human SQR. An active site disulfide is attacked by the incoming sulfide nucleophile and gives a persulfide and a free active site cysteine. The latter attacks the bound flavin forming a 4a adduct. Nucleophilic displacement by an acceptor (A) results in the transfer of the sulfane sulfur atom, reformation of the active site disulfide, and a two-electron reduction of the flavin.

It has been proposed that human SQR utilizes sulfite as the persulfide acceptor, forming thiosulfate (29). The recombinant human enzyme exhibits relatively high and similar catalytic efficiencies with cyanide or sulfite as acceptor but a significantly lower efficiency with sulfide as acceptor. However, the utilization of sulfite as the acceptor in cells poses at least a couple of problems. The first is teleological since sulfite is the product of persulfide dioxygenase (ETHE1, also known as sulfur dioxygenase), which is downstream of SQR in the oxidation pathway (Fig. 1). Hence, the production of sulfite is indirectly dependent on SQR. The second is an incompatibility with the clinical data as both H2S and thiosulfate levels are elevated in patients with ETHE1 deficiency (81). Since sulfite levels are greatly diminished in this condition, the observed accumulation of both the substrate (H2S) and putative product (thiosulfate) of the SQR reaction is not explained in these patients. Sulfite can be generated from cysteine catabolism via the successive action of cysteine dioxygenase and a transaminase to give cysteine sulfinic acid and β-sulfinylpyruvate, respectively followed by the decomposition of β-sulfinylpyruvate to sulfite and pyruvate (69, 73). However, the contribution of this pathway to sulfite production is expected to be minor under normal conditions but upregulated only under conditions of cysteine excess. Third, variants of ETHE1 are found in nature, which are fused to the sulfurtransferase, rhodanese. While this remains to be established, this genetic organization suggests that it increases the efficiency of utilization of sulfite, the product of the ETHE1 reaction, by rhodanese. Based on these considerations, the identity of the persulfide acceptor of mammalian SQRs remains to be established.

Persulfide dioxygenase (ETHE1)

ETHE1 is a soluble non-heme iron-containing sulfur dioxygenase (Fig. 5b) (46, 81) and is proposed to catalyze the second step in the mitochondrial sulfide oxidation pathway, that is, oxygenation of persulfide formed from H2S by SQR giving sulfite (25). It is not known if ETHE1 directly acts on the persulfide formed on SQR or indirectly following transfer of the SQR-bound persulfide to a small molecule carrier. Under in vitro assay conditions, glutathione persulfide serves as a substrate for ETHE1 (25, 81) exhibiting a KM value of 0.31±0.03 mM for the rat (25) and 0.34±0.03 mM for the human (33) protein. Coenzyme A persulfide serves as an alternate, albeit poor substrate for human ETHE1 while the persulfides of cysteine and homocysteine do not elicit dioxygenase activity (33).

Mutations in ETHE1 result in ethylmalonic encephalopathy (EE), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized with severe pathophysiological abnormalities leading to death in the first decade of life (80). Over 20 pathogenic mutations have been described in EE patients (48). ETHE1 knockout mice have increased H2S levels, 20-fold higher than in wild-type mice and low steady-state levels and activity of cytochrome c oxidase in luminal colonocytes, muscle and brain. Liver extracts from knockout mice exhibit threefold lower sulfide-dependent oxygen consumption and the animals die within 5–6 weeks after birth (81).

Interestingly, both ethe1−/− mice and patients with EE show increased levels of thiosulfate (81), which is puzzling since thiosulfate is postulated to be produced downstream of ETHE1 in the sulfide oxidation pathway. One explanation of this observation is that the persulfide generated by SQR is transferred to sulfite to form thiosulfate in a reaction catalyzed by rhodanese (Fig. 1), and that this reaction is enhanced in the absence of competition for the persulfide by ETHE1. As discussed above, the cysteine oxidation pathway represents an alternate route for generation of sulfite (69, 73). However, it is not known whether this pathway is a significant contributor of sulfite under conditions of ETHE1 deficiency.

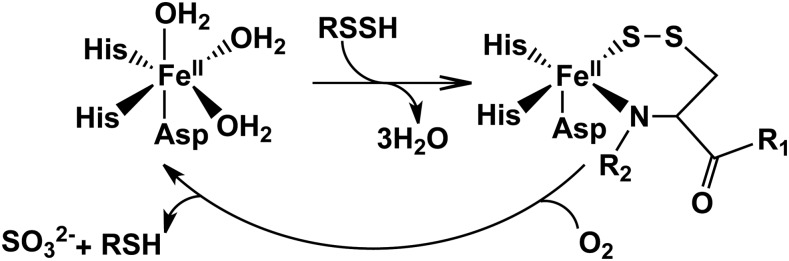

The detailed reaction mechanism of ETHE1 remains to be elucidated. The structure of the Arabidopsis ETHE1 reveals a dimeric protein with an active site iron coordinated by a 2-His-1-Asp facial triad (Fig. 5b) (46), a coordination geometry seen in a number of mononuclear non-heme iron(II) oxygenases (38). Although diverse, these enzymes share common elements in their reaction mechanisms. In most cases, the substrate and dioxygen bind to the active site iron(II). Oxygen activation progresses through internal electron transfer to form various intermediates, for example, the Fe(III)-superoxo and the Fe(III)-peroxo species. O-O bond cleavage then leads to formation of a high valent oxyferryl (Fe+4=O) species (45, 52, 64, 96) that is believed to be a key oxidant for substrate oxidation. In some dioxygenases, the substrate binds close to the iron center and the carboxylate of the facial triad functions as a bidentate ligand (38).

ETHE1 catalyzes a relatively distinct reaction from other members of the mononuclear iron-dependent dioxygenase superfamily, that is, the oxidation of the sulfane sulfur of a persulfide substrate (33) (Fig. 7). A similar reaction is catalyzed by cysteine dioxygenase (96), a cupin family dioxygenase, which oxidizes the sulfur of cysteine to form cysteine sulfinic acid, the first step in the cysteine degradation pathway. Yet, cysteine dioxygenase is different from the 2-His-1-carboxylate family in that all three protein-provided iron ligands in cysteine dioxygenase are histidine residues (45). Since the activity of ETHE1 is oxygen dependent, it is possible that its activity is downregulated under hypoxic conditions.

FIG. 7.

Overall reaction catalyzed by ETHE1. The resting form of the enzyme has water molecules coordinated to the vacant ligand sites at the 3-His-1-Asp mononuclear ferrous iron site. Binding of the substrate persulfide displaces the water molecules. Iron-based oxidation chemistry results in the formation of the products, sulfite and thiol.

Sulfane Sulfur as an H2S Store?

In principle, cells can harbor sulfide stores for mobilization in response to triggers, thus setting off H2S-dependent signaling. Sulfide can be stored as sulfane sulfur in which sulfur is covalently bonded to another sulfur atom. Examples of sulfane sulfur include protein-bound polysulfide (Protein-S-Sn-S-Protein) and persulfide, (Protein-S-SH) while examples of low-molecular weight compounds include inorganic polysulfide (R-Sn-R, where n≥3) and polythionate (−O3S-Sn-SO3−, where n≥1), thiosulfate (S2O32−) and elemental sulfur (S8).

Estimates of the sulfane sulfur pool size in rat tissues have furnished values of 324, 41, 34, and 19 nmol g−1 kidney, liver, spleen, and brain, respectively (60). Subcellular fractionation of liver and kidney revealed that approximately half of this pool is located in the cytoplasm. In HEK293 cells, the bound sulfur pool size (∼0.15 nmol mg−1 protein) reportedly increased ∼twofold in the presence of cysteine by overexpression of AAT/MST but not CBS (60). In a separate study, transfection of HEK293 cells with CSE enhanced protein S-sulphydration in the presence of cysteine (53). It is important to again emphasize that the choice of the H2S generating substrate used in studies can bias results about the contribution of the various H2S generating pathways. Hence, provision of exogenous cysteine stimulates CSE- and MST-dependent H2S biogenesis, whereas CBS-dependent H2S production is stimulated in the presence of cysteine and homocysteine (8, 11, 71).

Currently, there is neither evidence that stored sulfane sulfur is used in lieu of H2S for signaling nor mechanistic insights into how its utilization might be regulated. The disappearance of exogenous sulfide added to tissue homogenates has been described as “absorption” of sulfide and attributed to the formation of sulfane sulfur (27). However, additional possibilities exist to explain the disappearance of sulfide added to tissue homogenates including formation of disulfides and other oxidation products and catabolism via the mitochondrial oxidation pathway. The contributions of these processes need to be assessed. Since alkaline conditions favor the release of sulfane sulfur by physiological reductants such as glutathione, it has been suggested that astrocytes might be induced to release sulfane sulfur during repeated neuronal excitation (Fig. 8A) (27). Under these conditions, extracellular K+ concentrations increase leading to depolarization of astrocytes, activation of the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter and potentially, an increase in intracellular pH. An increase in the intracellular pH by 0.56 units was recorded in ∼60% of cultured astrocytes in the presence of 10 mM K+, of which 10% were more alkaline by 1.27 units. However, an increase in released sulfide could not be detected in this experiment and was attributed to the lack of sensitivity of the assay method (27). Clearly, the existence and utilization of general strategies for the regulated mobilization of sulfane sulfur pools in various cell types need to be studied to address the relevance of a storage pool to H2S signaling.

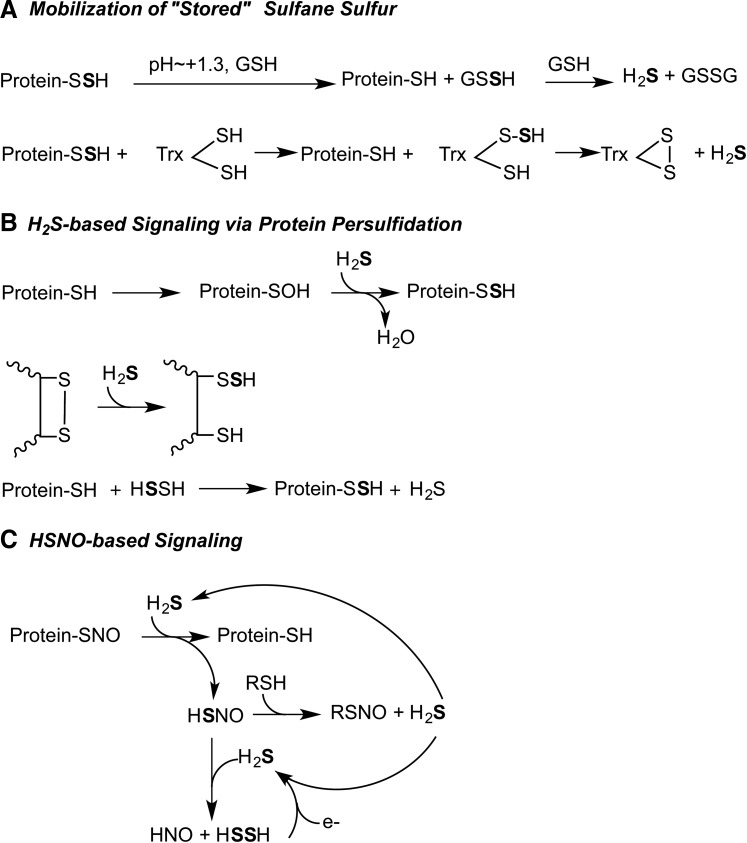

FIG. 8.

Proposed models for H2S-based signaling. (A) Sulfane sulfur is reactive and needs to be sequestered under cellular conditions. Release of H2S from persulfide is promoted under alkaline conditions and in the presence of a reductant such as glutathione (27). Alternatively, the sulfane sulfur can be transferred to an acceptor such as thioredoxin from where it is released as H2S with the concomitant oxidation of thioredoxin. (B) Formation of persulfide requires oxidation of the target protein to sulfenic acid or disulfide followed by attack of sulfide (32). Alternatively, H2S2, the two-electron oxidation product of H2S, can be attacked by a protein thiolate (59). (C) HSNO is formed by the reaction of H2S and S-nitrosated protein. HSNO can diffuse across the cell membrane and serve as a source of H2S or HNO depending on the whether the nucleophile attacks at the nitrogen or sulfur atom, respectively of HSNO (15). HSNO, thionitrous acid.

An underappreciated limitation with the concept of sulfane sulfur as a storehouse for H2S is the chemical reactivity of this post-translational modification. While the terminal sulfur in persulfides has dual reactivity and can function both as an electrophile and a nucleophile, the inner sulfur atom is electrophilic. Thus, due to the inherent instability of persulfides, stores if they exist, would have to be sequestered to have reasonable lifetimes in the cellular milieu.

H2S-Based Signaling via Persulfidation and Thionitrous Acid

While mechanisms for achieving specific persulfidation of target proteins or for releasing sulfide from the sulfane sulfur pool remain to be identified, the capacity for persulfidation to modulate cellular function was demonstrated by early studies by Vincent Massey on xanthine oxidase (44) and aldehyde oxidase (6), both of which have an active site persulfide that is essential for catalysis. In contrast, persulfide modification of rat liver tyrosine aminotransferase, which is CSE-dependent, leads to enzyme inactivation (23), and it is enhanced in experimental streptozotocin-induced diabetes (24). A crude fractionation of liver and kidney homogenates in this experiment indicated that sulfane sulfur exists in both low- and high-molecular weight fractions.

A recent proteomic analysis of persulfidation revealed that ∼10%–25% of liver proteins harbor this modification (53). Transfection of HEK293 cells with CSE enhanced persulfidation of three proteins that were monitored: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β-tubulin, and actin. However, the specificity of the modified biotin switch assay used to block free thiols and detect persulfides might not in fact have the required selectivity. Hence, caution needs to be exercised during identification of persulfides with this method. Persulfidation of GAPDH enhanced its activity while the same modification on actin, increased polymerization. Interestingly, S-nitrosylation and S-sulfhydration of GAPDH occur at the same cysteine residue and elicit opposite effects on catalytic activity (53), raising the possibility that the NO and H2S signaling systems compete for reactive cysteines in an overlapping set of target proteins.

The functional consequences of other proteins with persulfide modification have been characterized (54, 66). First, persulfidation of the antiapoptotic transcription factor, NF-κB, enhances DNA binding and is stimulated by TNFα, which increases H2S production via SP1-mediated transcriptional activation of CSE (66). The modified cysteine in the p65 subunit of NF-κB is targeted by S-nitrosylation and S-sulhydration with opposing functional effects. Second, persulfidation of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel causes hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation of rodent mesenteric arteries suggesting that H2S is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (54). Third, persulfidation of protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTP1B inhibited its activity and promoted the activity of PERK in response to ER stress (40).

Despite the growing number of protein targets being identified whose functions are influenced by persulfide modification, little attention has been paid to the mechanism by which H2S can modify cysteine residues. In the reducing intracellular milieu, cysteines are likely to exist predominantly in the thiol form, which is unreactive to H2S. Transient increases in reactive oxygen species concentration in response to triggers such as growth factor or cytokine signaling would increase the proportion of cysteines present in oxidized forms, for example, sulfenic acid and disulfides, both of which are reactive to H2S (Fig. 8B). Hydrogen persulfide, formed by two-electron oxidation of H2S, has been proposed as a possible cellular sulfhydration reagent (59). Alternatively, cellular alkanization leading to release of H2S from persulfide or more plausibly, activating the catalytic transfer of sulfane sulfur from sequestered “storage” sites to target proteins, for example, via the activity of thioredoxin, could result in persulfidation (Fig. 8A). This thioltransferase mechanism does not depend on prior oxidation of reactive cysteines on target proteins.

In light of the lack of emphasis on mechanisms underlying H2S-based protein modification, the recent discovery of thionitrous acid (HSNO), formed by reaction between H2S and S-nitrosothiols, is exciting (Fig. 8C) (15). HSNO can freely diffuse across membranes, connecting the intra- and extracellular signaling milieus, and can be a source of NO+ (during protein S-nitrosylation), NO• or HNO species, each with the potential for eliciting distinct physiological responses. Using a nitroxyl-sensitive fluorescent dye, strong evidence was obtained for the intracellular generation of HNO in endothelial cells. Formation of nitrosothiol from the reaction between H2S and NO• or peroxynitrite (ONOO−) was previously inferred and speculated to be important in blunting the effect of NO• (92). The discovery of HSNO expands the repertoire of redox-sensitive signaling molecules and provides a mechanism for crosstalk between the NO and H2S gas signaling pathways. This discovery explains the synergistic effect of H2S and NO on smooth muscle relaxation noted previously (26). The existence of HSNO raises questions about whether its formation is regulated by coupling of the activities of H2S-producing enzymes and NO synthase (15).

Summary

In these early days in the field of H2S biochemistry and signaling there are more questions than answers, representing an exciting place for the convergence of chemists, biochemists, and cell biologists. While a multitude of reactions yielding H2S catalyzed by the trans-sulfuration pathway enzymes have been identified (11, 71), there is little understanding of how the catalysts switch between the canonical and H2S-generating reactions. Further, the quantitative significance of the three catalysts, CBS, CSE, and MST for H2S production in different tissues needs to established using carefully designed assays that do not bias against the contributions of any enzyme. Similarly, critical questions remain unanswered regarding the enzymology of sulfide and persulfide oxidation including fundamental ones such as what is the physiological persulfide acceptor for SQR and the persulfide donor for ETHE1? While the activities of SQR and ETHE1 either indirectly or directly depend on oxygen thus lending them susceptible to hypoxic conditions, it is not known what other effectors might regulate them. Finally, the chemistry of the H2S-based signaling itself is mired in chemical complexity contributed in part by the experimental challenges with working with a redox-active gaseous signaling molecule and by its potential for interacting with the NO and CO signaling pathways. The resolution of these and other mechanistic questions pertinent to H2S homeostasis and signaling will be critical for moving the field ahead in the coming years.

Abbreviations Used

- AAT

aspartate aminotransferase

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- CSE

cystathionine γ-lyase (γ-cystathionase)

- EE

ethylmalonic encephalopathy

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ETHE1

sulfur or persulfide dioxygenase

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSSG

glutathione oxidized

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- HSNO

thionitrous acid

- MST

mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferases

- PERK

protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PLP

pyridoxal 5′-phosphate

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SP1

specificity protein 1

- SQR

sulfide quinone oxidoreductase

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL58984).

References

- 1.Agrawal N. and Banerjee R. Human polycomb 2 protein is a SUMO E3 ligase and alleviates substrate-induced inhibition of cystathionine beta-synthase sumoylation. PLoS One 3: e4032, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akagi R. Purification and characterization of cysteine aminotransferase from rat liver cytosol. Acta Med Okayama 36: 187–197, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartholomew TC, Powell GM, Dodgson KS, and Curtis CG. Oxidation of sodium sulphide by rat liver, lungs and kidney. Biochem Pharmacol 29: 2431–2437, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty PW. and Reed DJ. Involvement of the cystathionine pathway in the biosynthesis of glutathione by isolated rat hepatocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 204: 80–87, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birchmeier W. and Christen P. Syncatalytic enzyme modification: characteristic features and differentiation from affinity labeling. Methods Enzymol 46: 41–48, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branzoli U. and Massey V. Evidence for an active site persulfide residue in rabbit liver aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem 249: 4346–4349, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito JA, Sousa FL, Stelter M, Bandeiras TM, Vonrhein C, Teixeira M, Pereira MM, and Archer M. Structural and functional insights into sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase. Biochemistry 48: 5613–5622, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Jhee KH, and Kruger WD. Production of the neuromodulator H2S by cystathionine beta-synthase via the condensation of cysteine and homocysteine. J Biol Chem 279: 52082–52086, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherney MM, Zhang Y, James MN, and Weiner JH. Structure-activity characterization of sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase variants. J Struct Biol 178: 319–328, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherney MM, Zhang Y, Solomonson M, Weiner JH, and James MN. Crystal structure of sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans: insights into sulfidotrophic respiration and detoxification. J Mol Biol 398: 292–305, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiku T, Padovani D, Zhu W, Singh S, Vitvitsky V, and Banerjee R. H2S biogenesis by cystathionine gamma-lyase leads to the novel sulfur metabolites, lanthionine and homolanthionine, and is responsive to the grade of hyperhomocysteinemia. J Biol Chem 284: 11601–11612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis CG, Bartholomew TC, Rose FA, and Dodgson KS. Detoxication of sodium 35 S-sulphide in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol 21: 2313–2321, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Luca G, Ruggeri P, and Macaione S. Cystathionase activity in rat tissues during development. Ital J Biochem 23: 371–379, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickhout JG, Carlisle RE, Jerome DE, Mohammed-Ali Z, Jiang H, Yang G, Mani S, Garg SK, Banerjee R, Kaufman RJ, Maclean KN, Wang R, and Austin RC. Integrated stress response modulates cellular redox state via induction of cystathionine gamma-lyase: cross-talk between integrated stress response and thiol metabolism. J Biol Chem 287: 7603–7614, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipovic MR, Miljkovic J, Nauser T, Royzen M, Klos K, Shubina TE, Koppenol WH, Lippard SJ, and Ivanovic-Burmazovic I. Chemical characterization of the smallest S-nitrosothiol, HSNO; cellular cross-talk of H2S and S-nitrosothiols. J Am Chem Soc 134: 12016–12027, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkelstein JD, Kyle WE, Martin JL, and Pick AM. Activation of cystathionine synthase by adenosylmethionine and adenosylethionine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 66: 81–87, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furne J, Saeed A, and Levitt MD. Whole tissue hydrogen sulfide concentrations are orders of magnitude lower than presently accepted values. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1479–R1485, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehring H. and Christen P. Syncatalytic conformational changes in mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferases. Evidence from modification and demodification of Cys 166 in the enzyme from chicken and pig. J Biol Chem 253: 3158–3163, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goss SJ. Characterization of cystathionine synthase as a selectable, liver-specific trait in rat hepatomas. J Cell Sci 82: 309–320, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goubern M, Andriamihaja M, Nubel T, Blachier F, and Bouillaud F. Sulfide, the first inorganic substrate for human cells. FASEB J 21: 1699–1706, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griesbeck C, Schutz M, Schodl T, Bathe S, Nausch L, Mederer N, Vielreicher M, and Hauska G. Mechanism of sulfide-quinone reductase investigated using site-directed mutagenesis and sulfur analysis. Biochemistry 41: 11552–11565, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding HP, Zhang Y, and Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397: 271–274, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hargrove JL. Persulfide generated from L-cysteine inactivates tyrosine aminotransferase. Requirement for a protein with cysteine oxidase activity and gamma-cystathionase. J Biol Chem 263: 17262–17269, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hargrove JL, Trotter JF, Ashline HC, and Krishnamurti PV. Experimental diabetes increases the formation of sulfane by transsulfuration and inactivation of tyrosine aminotransferase in cytosols from rat liver. Metab Clin Exp 38: 666–672, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hildebrandt TM. and Grieshaber MK. Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. FEBS J 275: 3352–3361, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, and Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237: 527–531, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishigami M, Hiraki K, Umemura K, Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, and Kimura H. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 205–214, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishii I, Akahoshi N, Yu XN, Kobayashi Y, Namekata K, Komaki G, and Kimura H. Murine cystathionine gamma-lyase: complete cDNA and genomic sequences, promoter activity, tissue distribution and developmental expression. Biochem J 381: 113–123, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson MR, Melideo SL, and Jorns MS. Human sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase catalyzes the first step in hydrogen sulfide metabolism and produces a sulfane sulfur metabolite. Biochemistry 51: 6804–6815, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs RL, House JD, Brosnan ME, and Brosnan JT. Effects of streptozotocin-induced diabetes and of insulin treatment on homocysteine metabolism in the rat. Diabetes 47: 1967–1970, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarabak R. and Westley J. Steady-state kinetics of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase from bovine kidney. Arch Biochem Biophys 185: 458–465, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabil O. and Banerjee R. The redox biochemistry of hydrogen sulfide. J Biol Chem 285: 21903–21907, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabil O. and Banerjee R. Characterization of patient mutations in human persulfide dioxygenase (ETHE1) involved in H2S catabolism. J Biol Chem 287: 44561–44567, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabil O, Vitvitsky V, Xie P, and Banerjee R. The quantitative significance of the transsulfuration enzymes for H2S production in murine tissues. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 363–372, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabil O, Weeks CL, Carballal S, Gherasim C, Alvarez B, Spiro TG, and Banerjee R. Reversible heme-dependent regulation of human cystathionine beta-synthase by a flavoprotein oxidoreductase. Biochemistry 50: 8261–8263, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabil O, Zhou Y, and Banerjee R. Human cystathionine beta-synthase is a target for sumoylation. Biochemistry 45: 13528–13536, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaneko Y, Kimura Y, Kimura H, and Niki I. L-cysteine inhibits insulin release from the pancreatic beta-cell: possible involvement of metabolic production of hydrogen sulfide, a novel gasotransmitter. Diabetes 55: 1391–1397, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koehntop KD, Emerson JP, and Que L, Jr., The 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad: a versatile platform for dioxygen activation by mononuclear non-heme iron(II) enzymes. J Biol Inorg Chem 10: 87–93, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koj A, Frendo J, and Janik Z. [35S]thiosulphate oxidation by rat liver mitochondria in the presence of glutathione. Biochem J 103: 791–795, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnan N, Fu C, Pappin DJ, and Tonks NK. H2S-induced sulfhydration of the phosphatase PTP1B and its role in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Sci Signal 4: ra86, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levitt MD, Abdel-Rehim MS, and Furne J. Free and acid-labile hydrogen sulfide concentrations in mouse tissues: anomalously high free hydrogen sulfide in aortic tissue. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 373–378, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maclean KN, Gaustadnes M, Oliveriusova J, Janosik M, Kraus E, Kozich V, Kery V, Skovby F, Rudiger N, Ingerslev J, Stabler SP, Allen RH, and Kraus JP. High homocysteine and thrombosis without connective tissue disorders are associated with a novel class of cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) mutations. Hum Mutat 19: 641–655, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcia M, Ermler U, Peng G, and Michel H. The structure of Aquifex aeolicus sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, a basis to understand sulfide detoxification and respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 9625–9630, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Massey V. and Edmondson D. On the mechanism of inactivation of xanthine oxidase by cyanide. J Biol Chem 245: 6595–6598, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy JG, Bailey LJ, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Aceti DJ, Fox BG, and Phillips GN, Jr., Structure and mechanism of mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 3084–3089, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCoy JG, Bingman CA, Bitto E, Holdorf MM, Makaroff CA, and Phillips GN, Jr., Structure of an ETHE1-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62: 964–970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meister A, Fraser PE, and Tice SV. Enzymatic desulfuration of beta-mercaptopyruvate to pyruvate. J Biol Chem 206: 561–575, 1954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mineri R, Rimoldi M, Burlina AB, Koskull S, Perletti C, Heese B, von Dobeln U, Mereghetti P, Di Meo I, Invernizzi F, Zeviani M, Uziel G, and Tiranti V. Identification of new mutations in the ETHE1 gene in a cohort of 14 patients presenting with ethylmalonic encephalopathy. J Med Genet 45: 473–478, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morikawa T, Kajimura M, Nakamura T, Hishiki T, Nakanishi T, Yukutake Y, Nagahata Y, Ishikawa M, Hattori K, Takenouchi T, Takahashi T, Ishii I, Matsubara K, Kabe Y, Uchiyama S, Nagata E, Gadalla MM, Snyder SH, and Suematsu M. Hypoxic regulation of the cerebral microcirculation is mediated by a carbon monoxide-sensitive hydrogen sulfide pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 1293–1298, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mosharov E, Cranford MR, and Banerjee R. The quantitatively important relationship between homocysteine metabolism and glutathione synthesis by the transsulfuration pathway and its regulation by redox changes. Biochemistry 39: 13005–13011, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mudd SH, Levy HL, and Kraus JP. Disorders of transsulfuration. In: The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease, edited by Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, and Childs B. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2001, pp. 2007–2056 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukherjee A, Cranswick MA, Chakrabarti M, Paine TK, Fujisawa K, Munck E, and Que L, Jr., Oxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron centers: a superoxo perspective. Inorg Chem 49: 3618–3628, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, and Snyder SH. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal 2: ra72, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mustafa AK, Sikka G, Gazi SK, Steppan J, Jung SM, Bhunia AK, Barodka VM, Gazi FK, Barrow RK, Wang R, Amzel LM, Berkowitz DE, and Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor sulfhydrates potassium channels. Circ Res 109: 1259–1268, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagahara N, Ito T, Kitamura H, and Nishino T. Tissue and subcellular distribution of mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the rat: confocal laser fluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic studies combined with biochemical analysis. Histochem Cell Biol 110: 243–250, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagahara N. and Katayama A. Post-translational regulation of mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase via a low redox potential cysteine-sulfenate in the maintenance of redox homeostasis. J Biol Chem 280: 34569–34576, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagahara N, Okazaki T, and Nishino T. Cytosolic mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase is evolutionarily related to mitochondrial rhodanese. Striking similarity in active site amino acid sequence and the increase in the mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase activity of rhodanese by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 270: 16230–16235, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagahara N, Yoshii T, Abe Y, and Matsumura T. Thioredoxin-dependent enzymatic activation of mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. An intersubunit disulfide bond serves as a redox switch for activation. J Biol Chem 282: 1561–1569, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagy P. and Winterbourn CC. Rapid reaction of hydrogen sulfide with the neutrophil oxidant hypochlorous acid to generate polysulfides. Chem Res Toxicol 23:1541–1543, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogasawara Y, Isoda S, and Tanabe S. Tissue and subcellular distribution of bound and acid-labile sulfur, and the enzymic capacity for sulfide production in the rat. Biol Pharm Bull 17: 1535–1542, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prudova A, Albin M, Bauman Z, Lin A, Vitvitsky V, and Banerjee R. Testosterone regulation of homocysteine metabolism modulates redox status in human prostate cancer cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 1875–1881, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prudova A, Bauman Z, Braun A, Vitvitsky V, Lu SC, and Banerjee R. S-adenosylmethionine stabilizes cystathionine beta-synthase and modulates redox capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 6489–6494, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puranik M, Weeks CL, Lahaye D, Kabil O, Taoka S, Nielsen SB, Groves JT, Banerjee R, and Spiro TG. Dynamics of carbon monoxide binding to cystathionine beta-synthase. J Biol Chem 281: 13433–13438, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Que L, Jr., The oxo/peroxo debate: a nonheme iron perspective. J Biol Inorg Chem 9: 684–690, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ratnam S, Maclean KN, Jacobs RL, Brosnan ME, Kraus JP, and Brosnan JT. Hormonal regulation of cystathionine beta-synthase expression in liver. J Biol Chem 277: 42912–42918, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sen N, Paul BD, Gadalla MM, Mustafa AK, Sen T, Xu R, Kim S, and Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide-linked sulfhydration of NF-kappaB mediates its antiapoptotic actions. Mol Cell 45: 13–24, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, and Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem 146: 623–626, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, and Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 703–714, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singer TP. and Kearney EB. Intermediary metabolism of L-cysteinesulfinic acid in animal tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys 61: 397–409, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh S, Madzelan P, Stasser J, Weeks CL, Becker D, Spiro TG, Penner-Hahn J, and Banerjee R. Modulation of the heme electronic structure and cystathionine beta-synthase activity by second coordination sphere ligands: the role of heme ligand switching in redox regulation. J Inorg Biochem 103: 689–697, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh S, Padovani D, Leslie RA, Chiku T, and Banerjee R. Relative contributions of cystathionine beta-synthase and gamma-cystathionase to H2S biogenesis via alternative trans-sulfuration reactions. J Biol Chem 284: 22457–22466, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sliwa D, Dairou J, Camadro JM, and Santos R. Inactivation of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase contributes to the respiratory deficit of yeast frataxin-deficient cells. Biochem J 441: 945–953, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stipanuk MH. Metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Annu Rev Nutr 6: 179–209, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stipanuk MH, Londono M, Lee JI, Hu M, and Yu AF. Enzymes and metabolites of cysteine metabolism in nonhepatic tissues of rats show little response to changes in dietary protein or sulfur amino acid levels. J Nutr 132: 3369–3378, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taniguchi T. and Kimura T. Role of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the formation of the iron-sulfur chromophore of adrenal ferredoxin. Biochim Biophys Acta 364: 284–295, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taoka S. and Banerjee R. Characterization of NO binding to human cystathionine [beta]-synthase:: Possible implications of the effects of CO and NO binding to the human enzyme. J Inorg Biochem 87: 245–251, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taoka S, Ohja S, Shan X, Kruger WD, and Banerjee R. Evidence for heme-mediated redox regulation of human cystathionine beta-synthase activity. J Biol Chem 273: 25179–25184, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taoka S, West M, and Banerjee R. Characterization of the heme and pyridoxal phosphate cofactors of human cystathionine β-synthase reveals nonequivalent active sites. Biochemistry 38: 2738–2744, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Theissen U, Hoffmeister M, Grieshaber M, and Martin W. Single eubacterial origin of eukaryotic sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, a mitochondrial enzyme conserved from the early evolution of eukaryotes during anoxic and sulfidic times. Mol Biol Evol 20: 1564–1574, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tiranti V, D'Adamo P, Briem E, Ferrari G, Mineri R, Lamantea E, Mandel H, Balestri P, Garcia-Silva MT, Vollmer B, Rinaldo P, Hahn SH, Leonard J, Rahman S, Dionisi-Vici C, Garavaglia B, Gasparini P, and Zeviani M. Ethylmalonic encephalopathy is caused by mutations in ETHE1, a gene encoding a mitochondrial matrix protein. Am J Hum Genet 74: 239–252, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tiranti V, Viscomi C, Hildebrandt T, Di Meo I, Mineri R, Tiveron C, Levitt MD, Prelle A, Fagiolari G, Rimoldi M, and Zeviani M. Loss of ETHE1, a mitochondrial dioxygenase, causes fatal sulfide toxicity in ethylmalonic encephalopathy. Nat Med 15: 200–205, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ubuka T, Ohta J, Yao W-B, Abe T, Teraoka T, and Kurozumi Y. L-Cysteine metabolism via 3-mercaptopyruvate pathway and sulfate formation in rat liver mitochondria Amino Acids 2: 143–155, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ubuka T, Umemura S, Yuasa S, Kinuta M, and Watanabe K. Purification and characterization of mitochondrial cysteine aminotransferase from rat liver. Physiol Chem Phys 10: 483–500, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ueki I, Roman HB, Hirschberger LL, Junior C, and Stipanuk MH. Extrahepatic tissues compensate for loss of hepatic taurine synthesis in mice with liver-specific knockout of cysteine dioxygenase. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E1292–E1299, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vitvitsky V, Dayal S, Stabler S, Zhou Y, Wang H, Lentz SR, and Banerjee R. Perturbations in homocysteine-linked redox homeostasis in a murine model for hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R39–R46, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vitvitsky V, Garg SK, and Banerjee R. Taurine biosynthesis by neurons and astrocytes. J Biol Chem 286: 32002–32010, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vitvitsky V, Kabil O, and Banerjee R. High turnover rates for hydrogen sulfide allow for rapid regulation of its tissue concentrations. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 22–31, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vitvitsky V, Prudova A, Stabler S, Dayal S, Lentz SR, and Banerjee R. Testosterone regulation of renal cystathionine beta-synthase: implications for sex-dependent differences in plasma homocysteine levels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F594–F600, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vitvitsky V, Thomas M, Ghorpade A, Gendelman HE, and Banerjee R. A functional transsulfuration pathway in the brain links to glutathione homeostasis. J Biol Chem 281: 35785–35793, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wek RC. and Cavener DR. Translational control and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 2357–2371, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Westrop GD, Georg I, and Coombs GH. The mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase of Trichomonas vaginalis links cysteine catabolism to the production of thioredoxin persulfide. J Biol Chem 284: 33485–33494, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whiteman M, Li L, Kostetski I, Chu SH, Siau JL, Bhatia M, and Moore PK. Evidence for the formation of a novel nitrosothiol from the gaseous mediators nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 303–310, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu L, Yang W, Jia X, Yang G, Duridanova D, Cao K, and Wang R. Pancreatic islet overproduction of H2S and suppressed insulin release in Zucker diabetic rats. Lab Invest 89: 59–67, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yamamoto J, Sato W, Kosugi T, Yamamoto T, Kimura T, Taniguchi S, Kojima H, Maruyama S, Imai E, Matsuo S, Yuzawa Y, and Niki I. Distribution of hydrogen sulfide (H(2)S)-producing enzymes and the roles of the H(2)S donor sodium hydrosulfide in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol 17: 32–40, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, and Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science 322: 587–590, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ye S, Wu X, Wei L, Tang D, Sun P, Bartlam M, and Rao Z. An insight into the mechanism of human cysteine dioxygenase. Key roles of the thioether-bonded tyrosine-cysteine cofactor. J Biol Chem 282: 3391–3402, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yusuf M, Kwong Huat BT, Hsu A, Whiteman M, Bhatia M, and Moore PK. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the rat is associated with enhanced tissue hydrogen sulfide biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 333: 1146–1152, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]