Abstract

Objective:

Abnormalities of cognitive control functions, such as conflict and error monitoring, have been theorized to underlie obsessive-compulsive symptoms but only recently have been considered a potentially relevant psychological construct for understanding other forms of anxiety. The authors sought to determine whether these cognitive control processes elicit the same abnormalities of brain function in patients with pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as in those with non-OCD anxiety disorders.

Method:

Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the Multisource Interference Task was used to measure conflict- and error-related activations in youth (8–18 years) with OCD (n = 21) and non-OCD anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder; n = 23) compared with age-matched healthy controls (n = 25).

Results:

There were no differences in performance (accuracy, response times) among groups. However, a significant effect of group was observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) during error processing, driven by decreased activation in patients with OCD and those with non-OCD anxiety compared with healthy youth. Between patient groups, there was no difference in error-related dlPFC activation.

Conclusions:

Hypoactive dlPFC response to errors occurs in pediatric patients with OCD and those with non-OCD anxiety. These findings suggest that insufficient error-related engagement of the dlPFC associates with anxiety across traditional diagnostic boundaries and appears during the early stages of illness. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 2013;52(11):1183–1191.

Keywords: conflict, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, errors, pediatric anxiety disorders, pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder

Traditional diagnostic categories have led researchers to attempt to distinguish between the anxiety disorders, particularly obsessive-compulsive and other forms of anxiety1; however, distinct categories do not clearly map onto real-world clinical presentations. The overlapping phenomenology of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and non-OCD anxiety disorders presents diagnostic challenges, particularly in pediatric patients, because the boundary between obsession and worry can be especially blurry in children.2 This challenge is further complicated by high rates of comorbidity and developmental fluidity between OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders, with early-onset OCD and specific phobias predicting other forms of anxiety at later stages of development.3 Collectively, these lines of evidence suggest that OCD and non-OCD anxiety may occur along a single dimension and derive from common causal pathways, whereas expression may be shaped by developmental stage.4 Understanding whether the same psychological processes and their underlying neural substrate are shared across OCD and non-OCD forms of pediatric anxiety will inform mechanism-based strategies to prevent and treat anxiety from the early stages of illness.

Theoretically, failure to resolve conflict between intrusive worries and actual circumstance could contribute to OCD5 and non-OCD anxiety disorders. Strictly defined, conflict processing involves the detection of competition between conflicting response options and signaling for increased cognitive control to optimize performance when conflict is high.6 Errors represent a form of response conflict owing to competition between the actual and desired response.7 Given the key role of conflict and error processing in mediating behavioral adjustments,6 abnormality of these functions might contribute to the repetition of anxious thoughts and behaviors. Patients experience obsessions and worry as intrusive, unwanted, and difficult to control,8 despite evidence from the environment (e.g., reassurance from family and friends) and patients’ own insight9 that such thinking is not justified by circumstance. Common security concerns tend to evoke anxiety, even in healthy children, and might be especially potent in anxiety disorders,10 producing higher levels of conflict that can overwhelm cognitive control resources to drive repetitive thoughts (e.g., obsessions and/or worries) and related behaviors (e.g., compulsions and/or avoidance). Conversely, patients typically endorse insight that their anxiety-provoking thoughts “do not make sense,”8,9 raising the possibility that feared outcomes are appropriately detected as “thinking errors,”11 but that error detection fails to sufficiently engage cognitive control, so that anxious thoughts and behavior continue, without correction.

Conflict and errors activate a task control network that mediates the allocation of attentional resources to enable behavioral adjustments in response to these events.12 The posterior medial frontal cortex (pMFC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) are key nodes within this network, interacting to optimize performance. In healthy individuals, conflict and errors are detected by the pMFC, which signals for dlPFC engagement to increase cognitive control and optimize goal-directed behavior.6 Failure to adjust obsessive thinking and compulsive behavior, despite insight that feared outcomes are unlikely, suggests abnormalities of this network in OCD. Indeed, tasks requiring cognitive control have been associated with pMFC hyperactivation5,13-16 and decreased engagement of dlPFC17 in patients with OCD, even when OCD symptoms are not specifically triggered. Given the expected role of these regions,6 pMFC hyperactivation could reflect inefficient conflict or error detection, whereas dlPFC hypoactivation might reflect failure to appropriately engage the neural substrate for cognitive control18—either of which might lead to difficulty in adjusting the repetitive thoughts and behaviors characteristic of OCD.

In patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders, functional neuroimaging research has traditionally used emotion-inducing, rather than cognitive, conflict tasks, showing anxiety to associate with increased amygdala reactivity to threat.19 Some studies of non-OCD anxiety have examined cognitive control over emotion, showing excessive pMFC activation to emotional conflict20 but decreased dlPFC recruitment during tasks requiring the regulation of emotional response.21 During “pure” cognitive conflict, higher levels of trait anxiety in healthy adults associate with an exaggerated electrophysiologic response in an area of the midline prefrontal cortex that may localize to the pMFC22,23 but decrease dlPFC recruitment based on a study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).24 In addition, errors on cognitive conflict tasks induce an exaggerated, pMFC-localized electrophysiologic signal, the error-related negativity, in OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders.25 Taken together, these findings raise the possibility that excessive pMFC engagement and impoverished dlPFC engagement by conflict and errors may generalize across OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders.

To determine whether conflict and/or error monitoring represent useful constructs for characterizing the neural circuitry underlying a spectrum of pediatric anxiety, fMRI was used to measure pMFC and dlPFC responses to these cognitive control functions during the Multisource Interference Task (MSIT)26 in pediatric patients with OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders compared with healthy youth. The MSIT induces high levels of cognitive conflict and reliably engages the pMFC and dlPFC26—including in children.27 Based on extant literature, the authors hypothesized that patients from the 2 groups would exhibit pMFC hyperactivation and dlPFC hypoactivation during conflict and errors compared with healthy youth. By studying pediatric patients, the authors sought to determine whether the neural substrate for conflict and error monitoring is affected early in the illness course.

METHOD

Participants

Subjects were female, ranged in age from 8 to 19 years, and included 21 patients with OCD, 23 patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders, and 25 healthy youth. Anxiety disorders occur more commonly in female than in male youth, suggesting an influence of gender, and leading the authors to include female subjects only. There was no significant difference in age among groups (Table 1). All subjects underwent a structured clinical interview using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime Version,28 administered by a masters-level clinician with expertise in pediatric OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders. The Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CYBOCS)29 also was administered to patients with OCD. Pediatric subjects completed the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children30 and the Child Depression Inventory.31 Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).32 Subjects with serious medical or neurologic illness, head trauma, and mental retardation were excluded. Patients were excluded if they met the criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, any autistic spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Healthy subjects had no current or prior psychiatric illness. After a complete description of the study to the subjects and their parents, written informed assent and consent were obtained.

TABLE 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Group | OCD (n = 21) | AD (n = 23) | HC (n = 25) | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.9 (3.0) | 14.4 (2.9) | 14.1 (3.1) | 1.3 | .27 |

| CYBOCS | 18.7 (9.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MASCa | 55.4 (18.0) | 63.5 (18.6) | 31.3 (12.6) | 25.0 | <.001 |

| CDIa | 10.8 (7.7) | 14.8 (10.0) | 3.2 (3.7) | 14.8 | <.001 |

| CBCL_OCSb | 6.5 (3.6) | 3.6 (1.9) | 1.1 (0.88) | 31.0 | <.001 |

Note: AD = non–obsessive-compulsive anxiety disorders; CBCL_OCS = Child Behavior Checklist Obsessive Compulsive subscale; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; CYBOCS = Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; HC = healthy control; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; NA = not applicable.

Follow-up contrasts showed higher scores for patients with OCD and those with AD compared with healthy controls (p < .005 for all comparisons), but no significant difference between patient groups (MASC, p = .32; CDI, p = .24).

Follow-up contrasts showed higher scores for patients with OCD than for those with AD and for the 2 patient groups compared with HCs (p < .001 for all comparisons).

OCD was the primary diagnosis (i.e., primary source of lifetime impairment) in the OCD group. However, for feasibility and generalizability, the authors included secondary diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder (SAD; n = 1), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; n = 3), specific phobia (n = 1), panic disorder (n = 2), dysthymia (n = 2),and tics (n = 1), consistent with previously described clinical samples.33 Fourteen patients in the OCD group had no comorbid anxiety disorders, and 9 were diagnosed exclusively with OCD.

Patients in the non-OCD anxiety group had primary diagnoses of GAD (n = 14), social phobia (n = 6), or SAD (n = 3) and no current or lifetime history of OCD, consistent with recent fMRI research in pediatric anxiety.34 In the non-OCD anxiety group, 10 patients met the criteria for more than 1 non-OCD anxiety disorder (GAD plus specific phobia, n = 3; GAD plus SAD, n = 1; GAD plus panic disorder, n = 1; GAD plus social phobia, n = 4; SAD plus specific phobia, n = 1) and 1 met the criteria for major depression.

At the time of scanning, patients with OCD were experiencing mild to moderate symptom severity based on CYBOCS scores (Table 1); 18 were experiencing active OCD symptoms, whereas 3 were experiencing only subclinical symptoms (CYBOCS score <6). All patients in the non-OCD anxiety group met the DSM criteria for a current anxiety disorder diagnosis. Patients from the 2 groups reported higher levels of anxiety (Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children) and subclinical depressive symptoms (Child Depression Inventory) than controls (p < .001 for all comparisons) but did not differ significantly from one another (Table 1). Patients with OCD scored higher than patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders on the Obsessive-Compulsive subscale of the CBCL, which has been previously found to reliably distinguish OCD from clinical controls.35 All patients were unmedicated, except for a 13-year-old patient with OCD who was taking fluoxetine.

Task

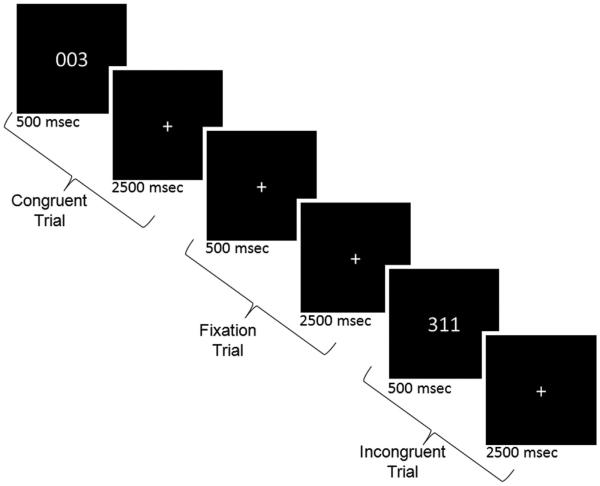

Participants performed the MSIT (Figure 126), which requires identification of the ordinal value of the unique number among 3 digits, “1,” “2,” or “3” (e.g., for “311,” the target is “3”) by pressing a key with 1 of 3 fingers (“1,” index finger; “2,” middle finger; “3,” ring finger). In the incongruent condition, cognitive conflict was generated by presenting the target in a position incongruent with its ordinal value (e.g., “3” presented at the first position) and flanked by different numbers (e.g., “11”). In the congruent condition, target placement was compatible with its ordinal value (e.g., “3” presented in the right position) and flanked by zeroes (e.g., “003”). In contrast to the original blocked version of the MSIT,36 the task was adapted for an event-related design to allow for the separation of fMRI blood oxygen level-dependent signal associated with correct incongruent, correct congruent, and error trials. MSIT stimuli appeared for 500 ms, followed by a 2,500-ms fixation cross, to comprise a trial. A total of 120 incongruent and 120 congruent trials were presented in pseudorandom order, intermingled with 60 fixation trials in which the 500-ms MSIT stimulus was replaced with a fixation cross. Fixed, pseudorandom ordering ensured that trials for a given condition were separated by variable intervals, ranging from 0 to 6 intervening trials of the other conditions, to maximize design sensitivity for differentiating trial types. Trials were presented over 5 runs (3 minutes each). Subjects were trained on the task in a MR simulator to ensure understanding of the task and decrease the novelty of the MR environment before actual scanning.

FIGURE 1.

Multisource interference task.

Scanning Parameters

A 3.0-T GE Signa scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) was used to acquire an axial T1-weighted image for alignment; a reverse spiral sequence37 for T2*- weighted images (gradient-recalled echo, repetition time = 2,000 ms, time to echo = 30 ms, fractional anisotropy = 90, field of view = 20 cm, 40 slices, 3.0 mm/slice, 64 × 64 matrix); and a high-resolution T1-weighted scan (3-dimensional spoiled gradient echo, 1.5-mm slices, 0 skip) for anatomic normalization. Subject head movement was minimized through instructions to the participant and packing with foam padding.

Preprocessing

Functional data were sinc interpolated, slice-time corrected,38 realigned to the tenth image acquired (“mcflirt”),39 and thresholded to exclude extraparenchymal voxels. Functional volumes were warped into common stereotactic space using the MNI152 template in SPM5.40 Excessive movement (>1 mm or degree on average, >3 mm or degrees for any repetition time) led to the exclusion of several runs (1 run: 2 OCD, 1 anxiety disorder, 1 control; 2 runs: 1 OCD, 1 control).

Analysis

Behavioral

Accuracy and response times were entered as dependent measurements in a repeated measures analysis of variance using group (OCD, non-OCD anxiety, healthy) as the between-subjects factor and condition (incongruent, congruent) as the within-subjects factor, covarying age. To test for between-group differences in motion, the square root of the sum square of translational and rotational movement parameters (from realignment) were submitted to 1-way analyses of variance (p < .05, 2-tailed). These analyses were conducted in SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Functional data were analyzed using a standard random effects analysis within the framework of the modified general linear model41 in SPM5. Correct incongruent, correct congruent, incorrect incongruent, and incorrect congruent trials were modeled against fixation trials as implicit baseline; omission error trials were modeled as a covariate of no interest. Correct incongruent and congruent trials were contrasted for each subject and entered into second-order random effects analyses to test the effect of conflict within (1-sample t tests) and between (F test) groups, covarying for age. For the error analysis, error trials were compared with correct trials for the incongruent condition; significantly more errors occurred on incongruent than congruent trials (p < .05), leading to the exclusion of congruent trials from the error analysis to avoid commingling the effects of errors and incongruence that might confound the interpretation of results. Only subjects with at least 5 commission errors on the incongruent condition were included, in accordance with prior work.6 Conflict and error contrasts were displayed at a peak threshold of p < .005 uncorrected. Significance was determined using a cluster-level α of 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons within a priori regions of interest (ROIs). For the pMFC, ROIs were the Anatomical Automatic Labeling atlas-defined right and left supplementary motor area (SMA), chosen based on the SMA location of conflict-related activation in healthy youth27 and hyperactivation in adult patients with OCD13 performing the MSIT. For the dlPFC, ROIs were defined by 10-mm spheres in the bilateral middle frontal gyri, centered on coordinates ( ± 34, 50, 22) derived from the study in which the MSIT was originally described.36 Based on the size of the ROIs and the smoothness of the present data, Monte Carlo simulations were conducted using AlphaSim in AFNI42 to determine the number of voxels needed to achieve cluster-level significance within each ROI. In addition, a whole-brain search was conducted using more stringent thresholds for significance, based on a cluster-level α of 0.05, correcting for family-wise error rates across the whole brain.41 Given evidence for developmental change in the neural circuitry for conflict and error processing,27 the main effects of age and interactions of group by age were tested across the whole brain and on mean contrast estimates extracted from ROIs.

Correlations With Behavioral Measurements

Contrast estimates were extracted from areas of group difference and tested for associations with clinical measurements (CYBOCS, CBCL Obsessive-Compulsive subscale, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, and Child Depression Inventory) within each group and behavioral measurements across all subjects, controlling for age, which can affect brain and behavioral responses to conflict and errors.27

RESULTS

Behavioral

Subjects were less accurate on incongruent than on congruent trials (Table 2), with a significant effect of condition (F1,65 = 4, p < .05), but no significant effect of group (F2,65 = 0.1, p = .92) or group-by-condition interaction (F2,65 = 0.9, p = .40). For response latencies, there was a significant effect of condition, with slower latencies for incongruent than for congruent trials (F1,65 = 68, p < .05), but no significant effect of group (F2,65 = 2.5, p = .09) or group-by-condition interaction (F2,65 = 1.5, p = .21).

TABLE 2.

Subject Performance

| Conflict Processing |

Error Processinga |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCD (n = 21) | AD (n = 23) | HC (n = 25) | OCD (n = 17) | AD (n = 13) | HC (n = 20) | |

| Accuracy | ||||||

| Incongruent | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.11 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.13 | 0.88 ± 0.06 |

| Congruent | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

| Commission errors | ||||||

| Incongruent | 12 ± 10 | 9 ± 12 | 10 ± 7 | 14 ± 10 | 14 ± 14 | 12 ± 7 |

| Congruent | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 |

| Omission errors | ||||||

| Incongruent | 2 ± 3 | 3 ± 4 | 2 ± 3 | 2 ± 4 | 4 ± 4 | 2 ± 3 |

| Congruent | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 3 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 2 ± 3 | 2 ± 2.4 |

| Response times | ||||||

| Incongruent | 1,119 ± 254 | 1,127 ± 259 1 | 1,007 ± 230 | 1,103 ± 265 | 1,088 ± 263 | 977 ± 235 |

| Congruent | 834 ± 239 | 808 ± 222 | 717 ± 184 | 809 ± 244 | 767 ± 231 | 702 ±197 |

Note: AD = non–obsessive-compulsive anxiety disorders; HC = healthy control; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Error processing analyses included only those subjects with at least 4 incongruent commission errors.

There were no between-group differences in head motion for translational (F2,66 = 0.6, p = .55) or rotational (F2,66 = 0.1, p = .95) movement.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

During conflict processing, all 3 groups showed activation of the pMFC and an extended network, including the midfrontal gyrus (dlPFC) and superior parietal cortex (Table S1, available online). Contrary to the authors’ prediction, there were no group effects in pMFC or dlPFC ROIs for conflict. Whole-brain analysis showed no significant findings for conflict.

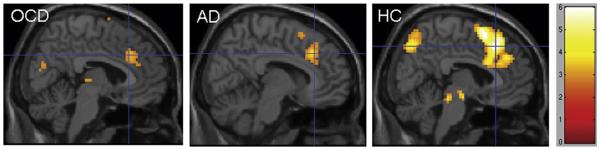

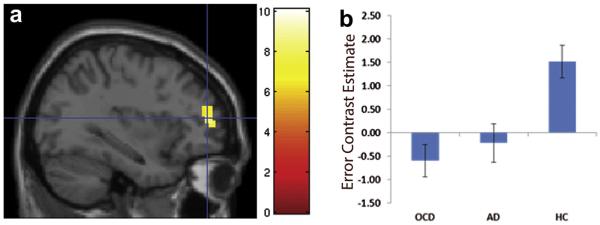

Seventeen patients with OCD, 13 with non-OCD anxiety disorders, and 20 healthy control subjects had sufficient numbers of incongruent commission errors for inclusion in the error analysis. Groups did not differ in number of errors (OCD: 13.9 ± 9.1, non-OCD anxiety disorders: 13.8 ± 9.1, healthy controls: 12.0 ± 7.2; F = 0.22, p = .81). During error processing, only healthy subjects activated the dlPFC, although all 3 groups showed robust activation of the pMFC (Figure 2, Table S2, available online). A significant group effect was observed within the left dlPFC ROI (−33, 48, 12, Z = 3.27; k = 41; Figure 3), driven by greater dlPFC activation in healthy youth compared with patients with OCD (t2,35 = −4.3, p <.001) and non-OCD anxiety disorders (t2,31 = −3.2, p = .003), whereas there was no significant difference between patient groups (t2,28 = −0.05, p = .50). Results for the error analysis were unchanged after excluding patients with OCD who had subclinical symptoms (n = 1) and comorbid anxiety disorders (n = 3).

FIGURE 2.

Error-related activations on incongruent trials for pediatric patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), non-OCD anxiety disorders (AD), and healthy controls (HC).

FIGURE 3.

(a) For error processing, a group effect was observed in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; (b) Extracted values from this area of group difference showed greater activation in healthy controls (HC) compared with patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or those with non-OCD anxiety disorders (AD). Note: The color bar indicates F values.

There were no significant main effects of age and no group-by-age interactions that met the criteria for significance. Contrast estimates extracted from the dlPFC area of group difference were not significantly correlated with clinical or behavioral variables.

DISCUSSION

Abnormalities of cognitive control functions, such as conflict and error monitoring, have been theorized to underlie obsessive-compulsive symptoms17 but only recently have been considered potentially relevant for understanding other forms of anxiety.24 To test whether brain-based alterations of these functions mark early illness in OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders, fMRI was performed during MSIT in pediatric patients with these 2 forms of anxiety. Compared with healthy youth, pediatric patients from the 2 anxiety groups exhibited hypoactivation of the dlPFC during error, but not during conflict, processing. This finding suggests that insufficient recruitment of the dlPFC in response to errors may represent a common mechanism across the general dimension of anxiety at early stages of development.

Consistent with prior work showing normal performance of conflict-inducing tasks in children with OCD43 and other anxiety disorders,44 behavioral response to conflict in the present patient sample did not differ from healthy controls. Indeed, children with these disorders often function well outside the context of their anxiety, suggesting that, although failure to engage dlPFC to errors may be present in patients even during the performance of a simple cognitive conflict task, it may only manifest as abnormal behavior in the context of anxiety-provoking stimuli or thoughts, which may be more sensitive to dlPFC dysfunction than performance on this interference task.

Recent work showing decreased dlPFC activation in high compared with low trait anxious adults during cognitive conflict suggests that impoverished recruitment of dlPFC-based substrate for cognitive control may associate with anxiety.24 In the present pediatric sample, dlPFC hypoactivation was found during errors in patients with OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorders compared with healthy controls, but no difference was found in the dlPFC (or elsewhere in the brain) between groups for conflict, even when the results were explored at very low thresholding (0.05, uncorrected). Discrepancy between the present results (dlPFC hypoactivation to errors) and those of Bishop24 (dlPFC hypoactivation to conflict) may stem from differences between samples and raises the possibility that age (pediatric versus adult) and/or symptom severity (anxiety disorders versus subclinical trait) may influence the context (errors versus conflict) in which associations between anxiety and deficient dlPFC recruitment for cognitive control are apparent. Nonetheless, failure to appropriately recruit the dlPFC in response to cognitive control demands in the 2 studies suggests a potentially relevant mechanism for anxiety across symptom subtypes, severity, and ages. Namely, insufficient capacity to engage dlPFC-based mechanisms for cognitive control could contribute to a deficient capacity for adjusting repetitive anxious thoughts and behavior.

Decreased dlPFC activation in the present sample of anxiety disordered youth argues against the processing efficiency theory of anxiety in which increased activation of the neural substrate for cognitive control is predicted. Based on mixed evidence of deficient performance in some, but not all, behavioral studies of attention in anxiety, this theory posits that increasing activation of the prefrontal substrate for cognitive control (e.g., dlPFC) may enable high anxious individuals to maintain normal performance, despite core deficits of attention.18 Extending this theory, Berggren and Derakshan18 suggested that such increases in prefrontal activation will be observed only when anxious individuals maintain normal task performance. Performance was not significantly different between patients with anxiety and healthy controls in the present sample. However, a trend-level effect of group on response times across trial types (p = .09) was observed, driven by a tendency for patients to respond more slowly than controls and consistent with a subtle decrement in performance. Manipulation of task difficulty and on-task anxiety level will be needed to elucidate whether variability in the quality of performance interacts with the degree of anxiety to influence decreases and increases in dlPFC activation.

Contrary to some prior neuroimaging work in adult OCD5,13,14 and 1 prior study in pediatric patients15 (but see Fitzgerald et al.45 and Woolley et al.46), the authors did not observe excessive engagement of the pMFC during conflict or error processing in youth with OCD or non-OCD anxiety disorders compared with healthy controls. This failure to demonstrate pMFC hyperactivation may have resulted from an insufficient sample size, particularly for error processing, because some of subjects committed too few errors (i.e., <5) to be included in the error analysis. During error processing, pMFC activation is more associated with error detection, whereas dlPFC engagement is believed to increase higher-order cognitive control to enable the adjustment of behavior in response to errors.6 Thus, it is possible that patients with early-stage OCD and non-OCD anxiety effectively recruit the pMFC for error detection but exhibit a deficiency of dlPFC recruitment for the fine tuning of behavior. Deficits of behavioral adjustment have been observed in larger samples of patients with pediatric OCD; specifically, Liu et al.47 observed a failure of post-error slowing—a behavioral correlate of dlPFC-based cognitive control6—in patients compared with controls. In the present much smaller sample, patients showed a similar decrease of post-error slowing (OCD: 62 ms, non-OCD anxiety disorders: 36 ms) compared with controls (93 ms) that did not reach statistical significance (p = .24). Future work, powered by higher rates of errors, should use trial-to-trial analyses to explore the extent to which atypical engagement of neural circuitry for behavioral adjustment, after errors, characterizes the broad dimension of anxiety in youth.

The present study has several limitations that bear consideration. Of the 21 patients included in the OCD sample, 3 were experiencing only subclinical OCD symptomatology at the time of the study entry, and 7 carried secondary diagnoses of non-OCD anxiety disorders. In addition, all subjects were female; thus, these findings may not extend to male patients with pediatric anxiety disorders. Sample sizes were small and included only patients affected by clinically significant anxiety; larger samples representing the full spectrum of anxiety severity are needed to increase the power to detect associations between error- and conflict-related activations and clinical or behavioral measurements. Some, but not all,5,14,15,48 prior fMRI studies of conflict and error processing in OCD have demonstrated an excessive pMFC response; thus, it is difficult to interpret the present failure to find error-related hyperactivation of the pMFC in this sample of patients with OCD and non-OCD anxiety disorder compared with healthy subjects. Future work using tasks designed to elicit higher error rates and larger samples may increase the power for detecting group differences in brain response to error processing. It should be noted that the authors sought to remain consistent with prior work15,27 by implementing interference and error contrasts at the subject level and testing for second-level group differences, rather than testing for group-by-condition interactions using a full factorial model. Moreover, the use of classification analyses to predict group membership and parametric manipulation of conflict to test for group-specific variation in response are needed to further characterize the role of error and conflict monitoring in anxious compared with healthy youth. Further, the study was designed to test for group differences in response to errors and conflict, leading the authors to match groups on age and covary age from the fMRI analyses; given that cognitive control develops dramatically during childhood and adolescence, when OCD and non-OCD anxiety tend to emerge,4 the possibility of differential developmental trajectories of error- and conflict-processing capacity should be explored in larger samples including more subjects—with and without anxiety—at each age.

In conclusion, hypoactivation of dlPFC response to errors occurs in pediatric patients with OCD and those with non-OCD anxiety disorders in the context of normal performance. These findings raise the possibility that decreased dlPFC recruitment for cognitive control may contribute to the dimension of anxiety, across traditional diagnostic boundaries, and from the early stages of illness. &

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grants K23MH082176 (K.D.F.), 1R01MH086517-01A2 (K.L.P., C.S.M.), R01 MH071821 (S.F.T.), and F32 MH082573 (E.R.S.); the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Awards (K.D.F., E.R.S.); and the Dana Foundation (K.D.F.).

The authors thank Georgia Stamatopoulos, M.S.W., Joanna Ingebritsen, B.A., and Keith Newhham of the University of Michigan for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

Disclosure: Dr. Taylor has received financial support for unrelated research from St. Jude Medical and Neuronetics. Drs. Fitzgerald, Liu, Stern, Welsh, Hanna, Monk, and Phan report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartz JA, Hollander E. Is obsessive-compulsive disorder an anxiety disorder? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:338–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comer JS, Kendall PC, Franklin ME, Hudson JL, Pimentel SS. Obsessing/worrying about the overlap between obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:663–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Zaslavsky AM. The role of latent internalizing and externalizing predispositions in accounting for the development of comorbidity among common mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:307–312. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283477b22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32:483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ursu S, Stenger VA, Shear MK, Jones MR, Carter CS. Overactive action monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:347–353. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.24411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerns JG, Cohen JD, MacDonald AW, III, Cho RY, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science. 2004;303:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1089910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung N, Botvinick MM, Cohen JD. The neural basis of error detection: conflict monitoring and the error-related negativity. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:931–959. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells A, Morrison AP. Qualitative dimensions of normal worry and normal obsessions: a comparative study. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:867–870. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muris P, Meesters C, Merckelbach H, Sermon A, Zwakhalen S. Worry in normal children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:703–710. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert P. The evolved basis and adaptive functions of cognitive distortions. Br J Med Psychol. 1998;71:447–463. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Miezin FM, et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yucel M, Harrison BJ, Wood SJ, et al. Functional and biochemical alterations of the medial frontal cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:946–955. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maltby N, Tolin DF, Worhunsky P, O’Keefe TM, Kiehl KA. Dysfunctional action monitoring hyperactivates frontal-striatal circuits in obsessive-compulsive disorder: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2005;24:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald KD, Stern ER, Angstadt M, et al. Altered function and connectivity of the medial frontal cortex in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huyser C, Veltman DJ, Wolters LH, de Haan E, Boer F. Developmental aspects of error and high-conflict-related brain activity in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a fMRI study with a Flanker task before and after CBT. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:1251–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menzies L, Chamberlain SR, Laird AR, Thelen SM, Sahakian BJ, Bullmore ET. Integrating evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder: the orbitofronto-striatal model revisited. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:525–549. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berggren N, Derakshan N. Attentional control deficits in trait anxiety: why you see them and why you don’t. Biol Psychol. 2013;92:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1476–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Heuvel OA, Veltman DJ, Groenewegen HJ, et al. Disorder-specific neuroanatomical correlates of attentional bias in obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and hypochondriasis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:922–933. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, Gross JJ. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:170–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser JS, Moran TP, Jendrusina AA. Parsing relationships between dimensions of anxiety and action monitoring brain potentials in female undergraduates. Psychophysiology. 2012;49:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Righi S, Mecacci L, Viggiano MP. Anxiety, cognitive self-evaluation and performance: ERP correlates. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop SJ. Trait anxiety and impoverished prefrontal control of attention. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:92–98. doi: 10.1038/nn.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olvet DM, Hajcak G. The error-related negativity (ERN) and psychopathology: toward an endophenotype. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1343–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bush G, Shin LM. The Multi-Source Interference Task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:308–313. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzgerald KD, Perkins SC, Angstadt M, et al. The development of performance-monitoring function in the posterior medial frontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3463–3473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, et al. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharm Bull. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:420–427. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Stanger C, et al. The Obsessive Compulsive Scale of the Child Behavior Checklist predicts obsessive-compulsive disorder: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bush G, Shin LM, Holmes J, Rosen BR, Vogt BA. The Multi-Source Interference Task: validation study with fMRI in individual subjects. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:60–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stenger VA, Boada FE, Noll DC. Multishot 3D slice-select tailored RF pulses for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:157–165. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aguirre GK, Zarahn E, D’Esposito M. Empirical analyses of BOLD fMRI statistics. II. Spatially smoothed data collected under null-hypothesis and experimental conditions. Neuroimage. 1997;5:199–212. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang E, Lee DS, Kang H, et al. Age-associated changes of cerebral glucose metabolic activity in both male and female deaf children: parametric analysis using objective volume of interest and voxel-based mapping. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1543–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Friston KJ, Evans AC. Characterizing the response of PET and fMRI data using multivariate linear models. Neuroimage. 1997;6:305–319. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward BD. Simultaneous inference for fMRI data. 2000 Feb 1; http://homepage.usask.ca/~ges125/fMRI/AFNIdoc/AlphaSim.pdf. Accessed. 2010.

- 43.Beers SR, Rosenberg DR, Dick EL, et al. Neuropsychological study of frontal lobe function in psychotropic-naive children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:777–779. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Micco JA, Henin A, Biederman J, et al. Executive functioning in offspring at risk for depression and anxiety. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:780–790. doi: 10.1002/da.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzgerald KD, Welsh RC, Gehring WJ, et al. Error-related hyperactivity of the anterior cingulate cortex in obsessive compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woolley J, Heyman I, Brammer M, Frampton I, McGuire PK, Rubia K. Brain activation in paediatric obsessive compulsive disorder during tasks of inhibitory control. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:25–31. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Gehring WJ, Weissman DH, Taylor SF, Fitzgerald KD. Trial-by-trial adjustments of cognitive control following errors and response conflict are altered in pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:41. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern ER, Welsh RC, Fitzgerald KD, et al. Hyperactive error responses and altered connectivity in ventromedial and frontoinsular cortices in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.