Abstract

The phosphoinositide 5-kinase PIKfyve and 5-phosphatase Sac3 are scaffolded by ArPIKfyve in the PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 (PAS) regulatory complex to trigger a unique loop of PtdIns3P – PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis and turnover. Whereas the metabolizing enzymes of the other 3-phosphoinositides have already been implicated in breast cancer, the role of the PAS proteins and the PtdIns3P – PtdIns(3,5)P2 conversion is unknown. To begin elucidating their role, in this study we monitored the endogenous levels of the PAS complex proteins in cell lines derived from hormone-receptor positive (MCF7 and T47D) or triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) (BT20, BT549 and MDA-MB-231) as well as in MCF10A cells derived from non-tumorigenic mastectomy. We report profound upregulation of Sac3 and ArPIKfyve in the triple-negative vs. hormone sensitive breast cancer or non-tumorigenic cells, with BT cell lines showing the highest levels. siRNA-mediated knockdown of Sac3, but not that of PIKfyve, significantly inhibited proliferation of BT20 and BT549 cells. In these cells, knockdown of ArPIKfyve had only a minor effect, consistent with a primary role for Sac3 in TNBC cell proliferation. Intriguingly, steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in BT20 and T47D cells were similar despite the 6-fold difference in Sac3 levels between these cell lines. Rather, steady-state levels of PtdIns3P and PtdIns5P, both regulated by the PAS complex, were significantly reduced in BT20 cells vs. T47D or MCF10A cell lines, consistent with elevated Sac3 affecting directly or indirectly the homeostasis of these lipids in TNBC. Together, our results uncover an unexpected role for Sac3 phosphatase in TNBC cell proliferation. Database analyses, discussed herein, reinforce the involvement of Sac3 in breast cancer pathogenesis.

Keywords: breast cancer; phosphoinositides; PtdIns(3,5)P2/PtdIns5P; PIKfyve; Sac3; ArPIKfyve

1. Introduction

Enhanced signaling through class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling cascade promotes oncogenesis and has been manifested in many human cancers [1,2]. In primary human breast cancers, alterations in one or more components of this pathway is described in more than 70% of the cases [3]. Thus, the p110 alpha catalytic subunit of class IA PI3 kinase (gene symbol PIK3CA), synthesizing PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 from PtdIns(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane, and/or Akt1, activated downstream of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 are frequently upregulated in breast cancer by somatic mutations or gene amplification [1–5] . Concordantly, loss of function of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10) that ceases the PI3K signaling by hydrolyzing PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to PtdIns(4,5)P2 is found in a number of breast carcinomas as a result of mutation or loss of heterozygosity [6,7]. Intriguingly, the metabolism of another 3- phosphorylated PI, i.e., PtdIns(3,4)P2, that could be produced through 5- dephosphorylation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is also implicated in breast cancer [7,8]. Concordantly, the inositolpolyphosphate 4-phosphatases INPP4A/B, hydrolyzing PtdIns(3,4)P2 to PtdIns3P, were found to function as tumor suppressors as evidenced by studies in both mouse and human models of breast cancer [1,2]. These data indicate that proper regulation of the phosphatases that turn over PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 plays a pivotal role in mammary tumorigenesis.

Another 3-phosphorylated PI is the low abundance PtdIns(3,5)P2 whose metabolism is controlled by an elaborate mechanism. It requires a triple protein complex that incorporates two enzymes with opposing activities, i.e., the phosphoinositide 5-kinase PIKfyve, synthesizing PtdIns(3,5)P2 from PtdIns3P, and the phosphoinositide 5- phosphatase Sac3 (single Sac1 domain-containing phosphatase 3, gene symbol FIG4), hydrolyzing PtdIns(3,5)P2 to PtdIns3P [9,10]. The enzymes are held together with the aid of a scaffold, i.e., ArPIKfyve (Associated regulator of PIKfyve; gene symbol VAC14) that binds them both and selectively prevents Sac3 rapid degradation [11–13]. The triple complex, referred to as the PAS complex (for PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3) promotes both synthesis and turnover of PtdIns(3,5)P2 [9,12,14]. PtdIns(3,5)P2 functions primarily in the endosomal system where, by regulating endosomal fusion and multivesicular body formation/fission, it controls endocytic trafficking to various destinations, such as lysosomes or the TGN and membrane recycling to the plasma membrane [10]. Compromised function of PIKfyve in the endosomal system has been already implicated in human cancers. Thus, impaired PIKfyve functionality attenuated EGFR nuclear trafficking, gene regulation and cell proliferation in human bladder carcinomas [15]. Likewise, perturbation of PIKfyve was found to reduce invasiveness in human NPM-ALK-positive lymphoma cells due to disturbed proper MMP9 maturation and intracellular localization [16]. The potential role of endosomal PtdIns(3,5)P2 and its metabolizing enzymes/regulators in breast cancer pathogenesis is currently unknown. To begin shedding some light on this issue, in the present study we examined the relative levels of the PAS complex proteins and related them to the steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2/PtdIns3P in several malignant neoplastic epithelial cells from primary human breast cancers, both hormone-receptor positive and triple-negative (TNBC). We report here that whereas PIKfyve protein levels only mildly varied among the breast cancer cells lines, levels of ArPIKfyve and Sac3 were markedly higher in the triple negative vs. hormone sensitive cell lines. We further reveal that siRNA-mediated silencing of Sac3, but not that of PIKfyve, in the TNBC cells is associated with dramatic reduction of cell proliferation. These results, taken together with available database information from functional genetic screening [17] suggest that the Sac3 phosphatase could be a new therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines

Human breast cancer cell lines were maintained as follows: MCF7, T47D, and MDA-MB-231 cells, in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% amphotericin B and 0.05% gentamicin; BT20 cells, in modified Eagle’s medium (MEM) containing 10% FBS, 1% amphotericin B, 0.05% gentamicin, 2% sodium bicarbonate, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% non-essential amino acids; BT549 cells, in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% amphotericin B, 0.05% gentamicin, 1 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 2% sodium bicarbonate, 1% sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L glucose, and 23 mU insulin (Humalog). Spontaneously immortalized MCF10A mammary gland cells were grown in 1:1 DMEM/Hams F12 medium, supplemented with 5% horse serum, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 10 μg/ml insulin, 1% L-glutamine, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells and differentiated mouse 3T3L1 adipocytes were maintained as specified previously [18].

2.2. siRNA-mediated silencing and cell proliferation assays

Smart Pool siRNA duplexes targeting human PIKfyve (#M-005058-03), Sac3 (cat. # M-019141-01) or ArPIKfyve (#M-015729-02) sequences and control cyclophilin B (#D-01136-01), purchased from ThermoFisher, were characterized previously [11,12,14]. Cells (~ 80% confluent 60 mm dishes) were transfected by the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent and 0.2 nmol of siRNA, following manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). In experiments using a combination of ArPIKfyve and Sac3 siRNAs, the control cells received 0.4 nmol cyclophilin B siRNA. Twenty-four hours post-transfection cells (150,000/dish) were reseeded in duplicate 35 mm dishes for each time point and counted on days 2, 4, 6 and 8 post-transfection by standard hemocytometer (Baxter). In parallel, 15,000 cells/well were seeded in triplicates in a 24-well dish for the MTT assay. On the indicated days, yellow MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma M2128) solution [100 μl of 5 mg MTT/ml PBS] was added to each well and cells were incubated for 4 hours. After medium removal, the intracellular water-insoluble purple product was dissolved in 1.0 ml of isopropanol, containing 4 mM HCl and 0.1% Nonidet P-40. The absorbance was read within 15 min on a spectrophotometer at 590 nm. Values were normalized from a standard curve of MTT formazan (Sigma M2003). Wells containing only medium were processed similarly in every experiment. Silencing was determined on day 3 and 6 after siRNA treatment by immunoblotting.

2.3. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were collected in RIPA+ buffer (radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer; 50 mM Tris.HCl, pH 8.0;150 mM NaCl; 1% Nonidet P-40; 0.5% Na deoxycholate), supplemented with 1x protease inhibitors as previously described ( [18]. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies as detailed [19]. Equal loading was verified by staining of the nitrocellulose membranes with Ponceau S solution (Sigma) prior to immunoblotting and by immunoblotting of stripped membranes with anti-GDI1 antibodies. Protein levels were normalized for the respective protein band signal in PC12 cells by laser scanning densitometry (Epson V700) and UN-SCAN-IT software (Silk Scientific). Several films of different exposure time were quantified to assure that the signals were within the linear range of sensitivity.

2.4. Myo-[2-3H] inositol cell labeling and HPLC analyses

BT20 and T7D breast cancer or MCF10A mammary epithelial cells were maintained overnight in glucose- and inositol-free cell type-specific medium and labeled for 30 hours with 25 μCi/ml following previously published protocols [20]. Cellular lipids were extracted, deacylated, and analyzed by HPLC (Waters 5215) on a 5-micron Partishere SAX column (Whatman). [32P]GroPIn standards were synthesized and co-injected as described elsewhere [18,20,21]. Fractions, collected every 0.25 min, were used for determination of [3H] and [32P] radioactivity after the addition of scintillation mixture. The integrated area of individual peak radioactivity was calculated as a percentage of the “total radioactivity”, i.e. the sum of all detected peaks for [3H]-GroPIns (-3P; -4P; -5P; - (3,5)P2; and –(4,5)P2), as detailed elsewhere [18].

2.5. Statistics

Data are given as mean +/− SE. Statistical analysis was done by Student’s t-test for independent samples with p<0.05 considered as significant.

3. Results and discussion

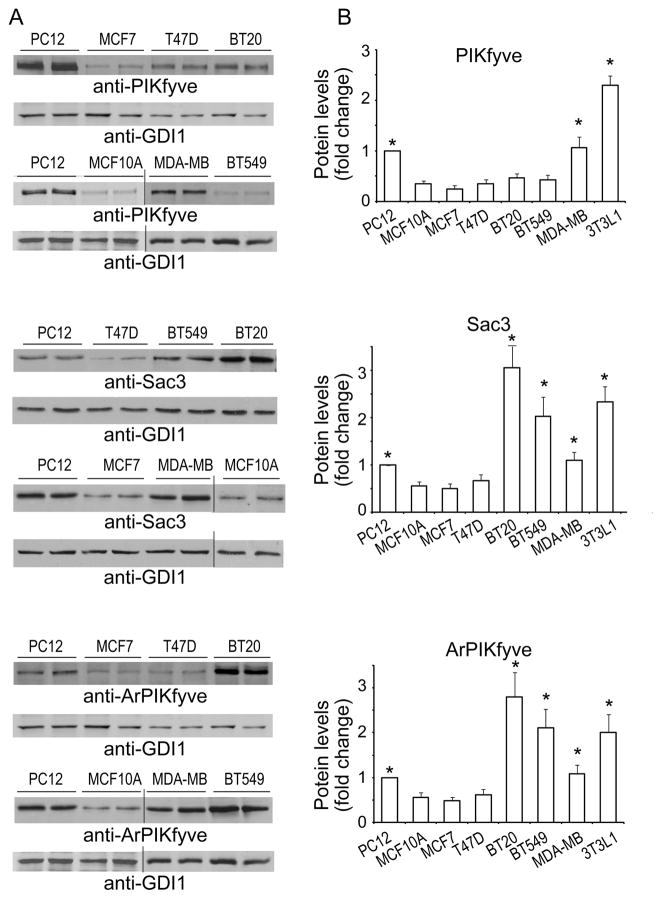

Whereas endogenous levels of the evolutionarily conserved PIKfyve, ArPIKfyve and Sac3 proteins have been documented in a number of mammalian cell types [11,14,19,22], insights about their expression and abundance in malignant cells, including human breast cancer cells, is elusive. In fact, among tumor cells, endogenous levels of the three proteins have been investigated only in pheochromocytoma tumor cells (PC12), where each of the three proteins was found to be expressed at high levels [11,14,23]. To start elucidating a potential role of the PAS complex proteins in breast cancer, we examined the presence and abundance of the three endogenous proteins in several human breast cancer cell lines, both hormone sensitive (MCF7 and T47D) and triple negative (BT20, BT549 and MDA-MB-231), by Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for endogenous protein. As controls for western blot normalization across experiments and protein quantification, we analyzed simultaneously MCF10A, a non-transformed epithelial cell line derived from human fibrocystic mammary tissue and/or PC12 tumor cells (Fig. 1A). Lysates from differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were also analyzed, as these cells express the three proteins at the highest levels among all cells tested thus far [19,23,24]. Quantitative analysis from five to seven independent experiments was performed for each cell line (Fig. 1B). Unexpectedly, we found that the hormone-sensitive MCF7 or T47D and the triple-negative BT cell lines exhibited relatively low levels of the PIKfyve protein, comparable to those of the control non-transformed MCF10A cells (Fig. 1). Only in the MDA-MB-231 cell line were the PIKfyve levels significantly elevated vs. the MCF10A control cells, reaching those of the PC12 cells but still below the 3T3L1 adipocytes’ high levels (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, levels of ArPIKfyve and Sac3 showed more pronounced differences among the cancer types. Thus, they both were significantly greater in the three TNBC cell lines compared to hormone-sensitive MCF7 and T47D cell lines. Intriguingly, whereas the relatively higher ArPIKfyve/Sac3 levels in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells were counterbalanced by proportional increases of the PIKfyve protein, ArPIKfyve and Sac3 in the BT20 or BT549 cell lines were elevated by 5–6-fold when normalized for their PIKfyve content (Fig. 1). These data indicate unprecedented increases of both ArPIKfyve and Sac3 vs. PIKfyve selectively in the triple negative BT cell lines.

Fig. 1.

ArPIKfyve and Sac3 are up-regulated in TNBC BT20, BT549 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Equal amount of cell RIPA+ lysates (150 μg protein) derived from indicated TNBC or hormone-sensitive breast cancer cell lines as well as from rat PC12 or differentiated mouse 3T3L1 adipocytes were used to determine protein levels of PIKfyve, ArPIKfyve and Sac3 by immunoblotting. A. Chemiluminescence detections of representative blots in duplicate samples for each of the three proteins out of five to seven experiments per cell line. Probing with anti-PIKfyve and anti-ArPIKfyve was performed on the upper and lower part of the same blot, respectively, subsequent to cutting the membrane horizontally at the 120 kDa protein marker. Equal loading was verified by probing with anti-GDI1. B. Quantitation of the band intensity for each protein expressed as a percentage of PC12 protein band run in the same experiment. Asterisks (*) denote statistical significance in each cell line vs. MCF10A cells (p<0.05).

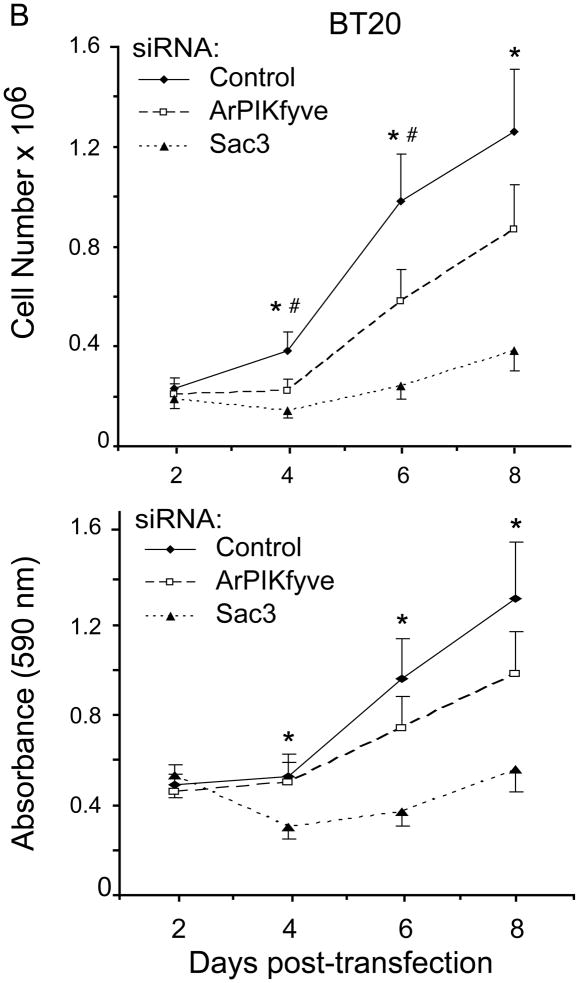

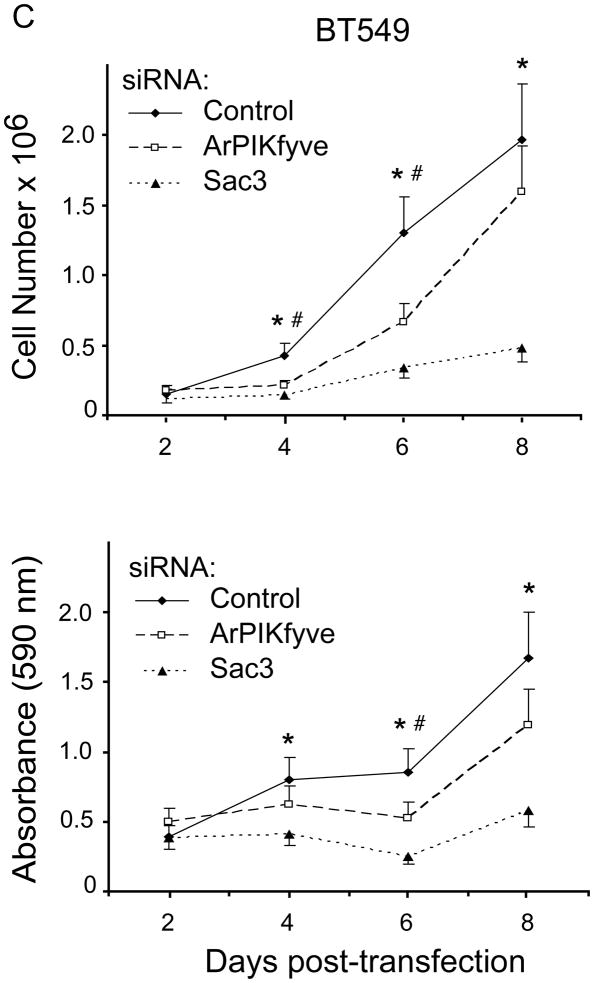

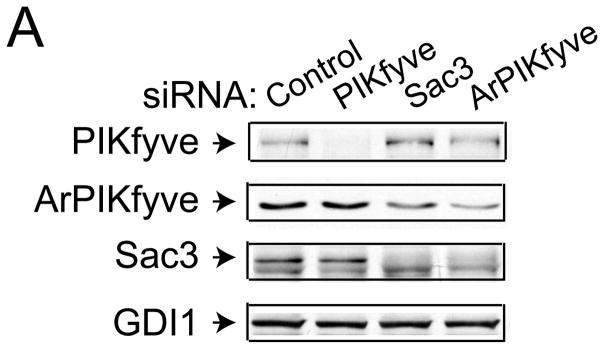

ArPIKfyve and Sac3 stably associate with each other independently of PIKfyve, which stabilizes the phosphatase and prevents its rapid degradation by the proteasome [13]. Concordantly, fibroblasts from mice with ArPIKfyve knockout (KO) have undetectable levels of Sac3, whereas HEK293 cells overexpressing ArPIKfyve have higher Sac3 [13,25]. The profound and coordinated upregulation of ArPIKfyve/Sac3 protein levels observed in the TNBC cells suggest the possibility that the two proteins may be involved in initiation/progression of triple-negative breast carcinomas. To test this hypothesis we assessed BT20 and BT549 cell proliferation subsequent to siRNA-mediated silencing of ArPIKfyve and Sac3 proteins, separately or in combination. We monitored cell proliferation over a period of 2–8 days subsequent to the siRNA treatment by two independent approaches: cell counting and MTT assays. Depletion of either protein was significant and stable, typically, 60–80% reduction vs. control levels, as determined on day 3 and 6 post transfection with the siRNA of individual proteins and with control siRNA (Fig. 2A and not shown). Consistent with the requirement of ArPIKfyve for preventing Sac3 degradation [13], silencing of ArPIKfyve caused specific reduction in Sac3 levels (Fig. 2A) in agreement with our previous observations [14]. Cell proliferation analyses by both approaches yielded similar results (Fig. 2B and C). Thus, as illustrated in Fig. 2B for BT20 cells and Fig. 2C, for BT549 cells, Sac3 silencing markedly inhibited cell proliferation as evidenced by the significant reduction in cell number or the MTT formazan absorbance vs. control cells over the time period of the study. Silencing of ArPIKfyve caused a marginal inhibitory effect, which could be attributed to the associated decrease in the Sac3 levels (Fig. 2) rather than an effect of ArPIKfyve per se. This conclusion is corroborated by the data from combined Sac3/ArPIKfyve protein depletion, which resulted in inhibition of cell proliferation to a degree similar to that seen by Sac3 silencing alone as measured by both approaches (Fig. 2). Thus, these data indicate that the decrease in the protein levels of the Sac3 phosphatase is the primary mechanism for the arrest in cell proliferation and suggest that the Sac3 levels should be decreased below a certain threshold for a maximum effect.

Fig. 2.

siRNA-mediated silencing of Sac3 but not ArPIKfyve significantly inhibits BT20 and BT549 and breast cancer cell proliferation. A-C, BT20 and BT549 cells were transfected with control (human cyclophilin B), Sac3 and ArPIKfyve human siRNAs to knock down the individual endogenous protein. A. Aliquots of fresh RIPA+ lysates (45 μg) derived from BT20 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies on day 3 post-transfection. Chemiluminescence detections of representative blots revealing ~60–80% decreases in the levels of the targeted proteins upon transfection with the corresponding siRNAs but not with control siRNA. Co-depletion of Sac3 by ArPIKfyve siRNA is specific as the presence of ArPIKfyve protects Sac3 from degradation. The slight diminution of ArPIKfyve by Sac3 siRNAs is unspecific off-target effect. (B) and (C), BT20 and BT549 cell proliferation quantified by cell counting (upper panels) and MTT assays (lower panels). At the indicated times post-transfections, cells were trypsinized and counted (upper panels) or processed by the MMT assay and absorbance (590 nM) measurement as described in Materials and Methods. Note the significant arrest in cell proliferation under Sac3 siRNA. The time course upon PIKfyve silencing overlaps the control, and is omitted for clarity. Combined ArPIKfyve + Sac3 depletion overlapped the curve for Sac3 and is also omitted for clarity. The data are from 3 separate experiments per cell line (mean + SEM). (*), difference between control and Sac3; (#), difference between control and ArPIKfyve, (p<0.05).

Intriguingly, similar analyses in the two BT cell lines revealed that siRNA-mediated PIKfyve silencing failed to significantly affect cell proliferation. In fact, the time course was similar to that observed with control siRNAs (Fig. 2B & C). Likewise, PIKfyve depletion in the triple negative MDA-MB-231 cells that exhibit greater PIKfyve levels (see Fig. 1) also failed to significantly alter the rate of cell proliferation (not shown). Collectively, these data indicate markedly attenuated cell proliferation by selective knockdown of the Sac3 phosphatase in the BT cell lines consistent with the notion that higher Sac3, and perhaps altered PtdIns(3,5)P2, might be associated with breast cancer development and/or progression in TNBC cells.

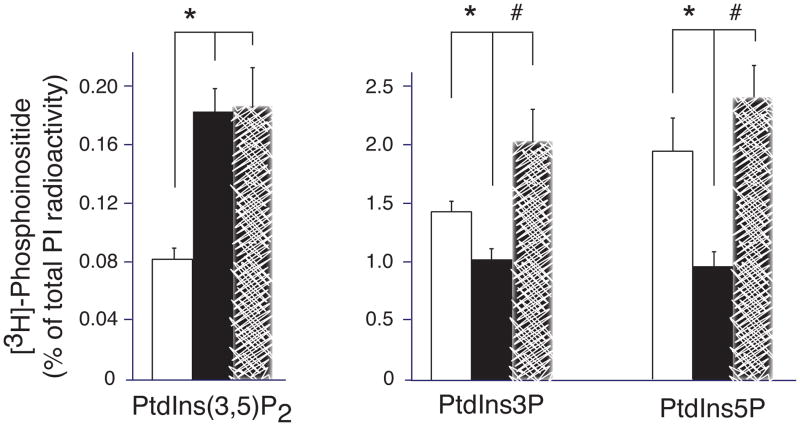

As indicated above, the Sac3 phosphatase is required for both PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis from and turnover to PtdIns3P [9,12,14]. When Sac3 levels are increased in the HEK293 stable cell line by overexpression of ArPIKfyve that prevents Sac3 degradation, PtdIns(3,5)P2 turnover overrides synthesis, as judged by the slight decrease of PtdIns(3,5)P2 and the commensurate increase of PtdIns3P [13]. To reveal whether the observed greater levels of Sac3 (along with ArPIKfyve; Fig. 1) in the BT20 cell line will similarly accelerate PtdIns(3,5)P2 turnover, we assessed the phosphoinositide profile by HPLC inositol-headgroup analysis subsequent to cell labeling with myo-[2-3H]inositol. As a control, we used non-transformed MCF10A mammary epithelial cells that have about 6-fold less Sac3 and equal PIKfyve levels vs. BT20 cells (see Fig. 1). Unexpectedly, we observed that the BT20 cells had significantly elevated steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 and reduced PtdIns3P, consistent with the notion that under the pathophysiological conditions elevated Sac3 phosphatase promotes PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis, rather than turnover (Fig. 3). Steady-state levels of PtdIns5P that are also controlled, entirely or partially, by the PIKfyve and Sac3 enzymatic activities [26] were significantly reduced vs. MCF10A cells. To reveal whether this relative increase in steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 is specific for the triple negative BT20 cells, we further analyzed the phosphoinositide profiles in the hormone-sensitive T47D breast cancer cells that exhibit similar PIKfyve protein levels but nearly 6-fold reduction in Sac3 vs. BT20 cells (see Fig. 1). Intriguingly, we observed that steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in T47D cells were similar to those in BT20 despite the profound difference in Sac3 levels between the two cells lines (Fig. 3). These data suggest that in the breast cancer cells, steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 are not directly dependent on the amount of Sac3 protein, implying additional mechanisms controlling PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels in breast cancer. The 2-2.5-fold decline in steady-state levels of PtdIns3P and PtdIns5P in BT20 vs. T47D cells allows the speculation that dysregulated PIKfyve functionality, and perhaps that of other PI kinases/phosphatases as a result of Sac3 protein elevation, may account for our observations (Fig. 3). At any rate, our phosphoinositide analysis does not support the notion that elevated Sac3 in the TNBC results in reduced steady-state levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2.

Fig. 3.

Steady-state levels of PIs regulated by the PAS complex in triple-negative and hormone sensitive breast cancer cell lines. Indicated cell lines were metabolically labeled with myo-[2-3H]-inositol. Extracted lipids were deacylated and the GroPIns resolved by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as % of the total PIs (mean + SE) from 3 separate experiments per cell line. (*), statistically significant differences between BT20 and MCF10A cells; (#) statistically significant differences between BT20 and T47D cells (p<0.05).

The data presented in this study demonstrate unprecedented elevation of endogenous Sac3 protein in the triple negative BT breast cancer cell lines, linked with enhanced proliferative capacity of these cells. While the molecular mechanism of coordinated ArPIKfyve/Sac3 upregulation and participation of the ArPIKfyve/Sac3 sub-complex in breast cancer cell proliferation remains to be elucidated, it is highly significant that a recent high throughput study using a lentivirus-driven short hairpin RNA library to silence ~16000 genes [17] has found Sac3 silencing to be associated with reduced cell proliferation in 45% of the investigated breast cancer cell lines. This unexpected high frequency could be better appreciated upon comparison to genes considered critical in breast tumorigenesis, such as PIK3CA or AKT1 [1], the silencing of which inhibited significantly (p<0.1) breast cancer cell proliferation in only 28% and 24% of the cases, respectively [17]. Furthermore, our detailed analysis of data in [17] made the stunning observation that Sac3 was the most frequently implicated in breast cancer cell proliferation among all known phosphoinositide-metabolizing enzymes, including PIK3CA, INPP4, PTEN and MTM/MTMRs. Moreover, this analysis has further indicated a higher frequency for Sac3 requirement in proliferation of triple-negative breast cancer cell lines, including the ones tested herein (BT and MDA-MB-231) and less so, in hormone sensitive MCF7 and T47D. The essential role of the Sac3 phosphatase, rather than that of the PIKfyve kinase in breast cancer initiation/progression, as suggested by our observations for the ineffectiveness of the siRNA-mediated PIKfyve silencing in proliferation of TNBC cell lines, is further substantiated by findings for similar ineffectiveness of lentivirus shRNA-mediated silencing of PIKfyve in proliferation of TNBC and hormones sensitive breast cancer cells [17].

The notion that Sac3 enhances breast cancer cell proliferation raises the question as to possible human breast cancer-associated mutations in Sac3 and/or the ArPIKfyve scaffold that enhances the phosphatase stability and lifespan [13,25]. A search of the available public database (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/) revealed that somatic mutations in Sac3 or ArPIKfyve are very rare, 2 (0.2%) and 5 (0.5%) out of 962 studied human breast cancer samples, respectively. Likewise, no cases of high-level amplification (above 7x) are reported for both genes in 45 breast cancer specimens. Unexpectedly, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was found in 33% (15/45; Sac3) and 49% (22/45, ArPIKfyve) in these specimens. How LOH of ArPIKfyve/Sac3 is translated to initiation and/or progression of the different breast cancer subtypes certainly warrants further investigation. In any case, the present results demonstrate for the first time upregulation of Sac3 protein levels in the TNBC cell lines linked with enhanced TNBC cell proliferation and provide the prospect that potential drug targeting of Sac3 may improve therapeutic outcomes of the more aggressive TNBC subtype.

Highlights.

We assess PAS complex proteins and phosphoinositide levels in breast cancer cells

Sac3 and ArPIKfyve are markedly elevated in triple-negative breast cancer cells

Sac3 silencing inhibits proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines

Phosphoinositide profiles are altered in breast cancer cells

This is the first evidence linking high Sac3 with breast cancer cell proliferation

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda McCraw for the outstanding secretarial assistance. The senior author expresses gratitude to the late Violeta Shisheva for her many years of support. This project was supported by National Institute of Health (DK58058) and American Diabetes Association (7-13-BS-161) (to AS).

Abbreviations

- PtdIns

phosphatidylinositol

- PI

phosphoinositides

- PIKfyve

PhosphoInositide Kinase for position five containing a fyve domain

- ArPIKfyve

Associated regulator of PIKfyve

- Sac3

Sac1 domain-containing phosphatase 3

- PAS complex

PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 complex

- GroPIns

glycerophosphorylinositol

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

Footnotes

Disclosure statement. The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ognian C. Ikonomov, Email: oikonomo@med.wayne.edu.

Catherine Filios, Email: cfilios@med.wayne.edu.

Diego Sbrissa, Email: dsbrissa@med.wayne.edu.

Xuequn Chen, Email: xchen@med.wayne.edu.

References

- 1.Wong KK, Engelman JA, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K signaling pathway in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertucci MC, Mitchell CA. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and INPP4B in human breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1280:1–5. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Knowles E, O'Toole SA, McNeil CM, Millar EK, Qiu MR, Crea P, Daly RJ, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. PI3K pathway activation in breast cancer is associated with the basal-like phenotype and cancer-specific mortality. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1121–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Liu G, Dziubinski M, Yang Z, Ethier SP, Wu G. Comprehensive analysis of oncogenic effects of PIK3CA mutations in human mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:217–27. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9847-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, Donoho GP, Briggs SL, Robbins CM, Hostetter G, Boguslawski S, Moses TY, Savage S, Uhlik M, Lin A, Du J, Qian YW, Zeckner DJ, Tucker-Kellogg G, Touchman J, Patel K, Mousses S, Bittner M, Schevitz R, Lai MH, Blanchard KL, Thomas JE. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–44. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma K, Cheung SM, Marshall AJ, Duronio V. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 levels correlate with PKB/akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473, respectively; PI(3,4)P2 levels determine PKB activity. Cell Signal. 2008;20:684–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedele CG, Ooms LM, Ho M, Vieusseux J, O'Toole SA, Millar EK, Lopez-Knowles E, Sriratana A, Gurung R, Baglietto L, Giles GG, Bailey CG, Rasko JE, Shields BJ, Price JT, Majerus PW, Sutherland RL, Tiganis T, McLean CA, Mitchell CA. Inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase II regulates PI3K/Akt signaling and is lost in human basal-like breast cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22231–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015245107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazawa K. Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatases: How do they affect tumourigenesis? J Biochem. 2013;153:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Fenner H, Shisheva A. PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 core complex: contact sites and their consequence for Sac3 phosphatase activity and endocytic membrane homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35794–806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shisheva A. PIKfyve and its lipid products in health and in sickness. Curr Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2012;362:127–62. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5025-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Strakova J, Dondapati R, Mlak K, Deeb R, Silver R, Shisheva A. A mammalian ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Vac14 that associates with and up-regulates PIKfyve phosphoinositide 5-kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10437–47. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10437-10447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Fenner H, Shisheva A. ArPIKfyve homomeric and heteromeric interactions scaffold PIKfyve and Sac3 in a complex to promote PIKfyve activity and functionality. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:766–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Fligger J, Delvecchio K, Shisheva A. ArPIKfyve regulates Sac3 protein abundance and turnover: disruption of the mechanism by Sac3I41T mutation causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth 4J disorder. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26760–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.154658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Fu Z, Ijuin T, Gruenberg J, Takenawa T, Shisheva A. Core protein machinery for mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate synthesis and turnover that regulates the progression of endosomal transport. Novel Sac phosphatase joins the ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23878–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Jahng WJ, Di Vizio D, Lee JS, Jhaveri R, Rubin MA, Shisheva A, Freeman MR. The phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve mediates epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking to the nucleus. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9229–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupuis-Coronas S, Lagarrigue F, Ramel D, Chicanne G, Saland E, Gaits-Iacovoni F, Payrastre B, Tronchere H. The NPM-ALK oncogene interacts, activates and uses PIKfyve to increase invasiveness. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32105–32114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh JL, Brown KR, Sayad A, Kasimer D, Ketela T, Moffat J. COLT-Cancer: functional genetic screening resource for essential genes in human cancer cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D957–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Filios C, Delvecchio K, Shisheva A. Functional dissociation between PIKfyve-synthesized PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 by means of the PIKfyve inhibitor YM201636. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C436–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Dondapati R, Shisheva A. ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve interaction and role in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2404–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Xie Y, Jin JP, Rappolee D, Shisheva A. The Phosphoinositide Kinase PIKfyve Is Vital in Early Embryonic Development: PREIMPLANTATION LETHALITY OF PIKfyve−/− EMBRYOS BUT NORMALITY OF PIKfyve+/− MICE. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13404–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. Acquisition of unprecedented phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate rise in hyperosmotically stressed 3T3-L1 adipocytes, mediated by ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7883–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Shisheva A. PIKfyve, a mammalian ortholog of yeast Fab1p lipid kinase, synthesizes 5-phosphoinositides. Effect of insulin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21589–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborne SL, Wen PJ, Boucheron C, Nguyen HN, Hayakawa M, Kaizawa H, Parker PJ, Vitale N, Meunier FA. PIKfyve negatively regulates exocytosis in neurosecretory cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2804–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shisheva A, DeMarco C, Ikonomov O, Sbrissa D. PIKfyve and acute insulin actions. In: In Sima A, Shafrir eE, editors. Insulin Signaling: From Cultured Cells to Animal Models. 2002. pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenk GM, Ferguson CJ, Chow CY, Jin N, Jones JM, Grant AE, Zolov SN, Winters JJ, Giger RJ, Dowling JJ, Weisman LS, Meisler MH. Pathogenic mechanism of the FIG4 mutation responsible for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease CMT4J. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shisheva A. PtdIns5P: News and views of its appearance, disappearance and deeds. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]