Abstract

Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 17895 possesses an array of mono- and dioxygenases, as well as hydratases, which makes it an interesting organism for biocatalysis. R. rhodochrous is a Gram-positive aerobic bacterium with a rod-like morphology. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. The 6,869,887 bp long genome contains 6,609 protein-coding genes and 53 RNA genes. Based on small subunit rRNA analysis, the strain is more likely to be a strain of Rhodococcus erythropolis rather than Rhodococcus rhodochrous.

Keywords: Rhodococcus rhodochrous, Rhodococcus erythropolis, biocatalysis, genome

Introduction

The genus Rhodococcus comprises genetically and physiologically diverse bacteria, known to have a broad metabolic versatility, which is represented in its clinical, industrial and environmental significance. Their large number of enzymatic activities, unique cell wall structure and suitable biotechnological properties make Rhodococcus strains well-equipped for industrial uses, such as biotransformation and the biodegradation of many organic compounds. In the environmental field, the ability of Rhodococcus to degrade trichloroethene [1], haloalkanes [2-4], and dibenzothiophene (DBT) [5] is reported. Furthermore, its potential for petroleum desulfurization is known [5].

Rhodococcus rhodochrous strains are ubiquitous in nature. They possess an array of mono- and dioxygenases, as well as hydratases, which make them an interesting organism for biocatalysis [6]. One example would be the recently reported regio-, diastereo- and enantioselective hydroxylation of unactivated C-H bonds [7] which remains a challenge for synthetic chemists, who often rely on differences in the steric and electronic properties of bonds to achieve regioselectivity [8]. Furthermore, most Rhodococcus strains harbor nitrile hydratases [9-11], a class of enzymes used in the industrial production of acrylamide and nicotinamide [12] while other strains are capable of transforming indene to 1,2-indandiol, a key precursor of the AIDS drug Crixivan [13]. In another recent example, R. rhodochrous ATCC BAA-870 was used for the biocatalytic hydrolysis of β-aminonitriles to β-amino-amides [14]. One example for a rather rarely investigated reaction would be the biocatalytic hydration of 3-methyl- or 3-ethyl-2-butenolide from the corresponding (R)-3-hydroxy-3-alkylbutanolide, a phenomenon observed in resting cells of Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 [15].

In order to obtain a comprehensive understanding of its high ability for biodegradation and biotransformation [16], the genome of R. rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 was sequenced. To the best of our knowledge, no complete genome sequence of this organism can be found in the literature. Here we present a summary, classification and a set of features for R. rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 together with the description of the genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

Bacteria from the Rhodochrous group are taxonomically related to the genera Nocardia and Mycobacterium. In 1977 Goodfellow and Alderson proposed the genus Rhodococcus to be assigned to this group [17]. This assignment is due to the overlapping characteristics with Nocardia and Mycobacterium that were studied in morphological, biochemical, genetic, and immunological studies [18]. R. rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 was previously deposited as Nocardia erythropolis [19] and Rhodococcus erythropolis [17].

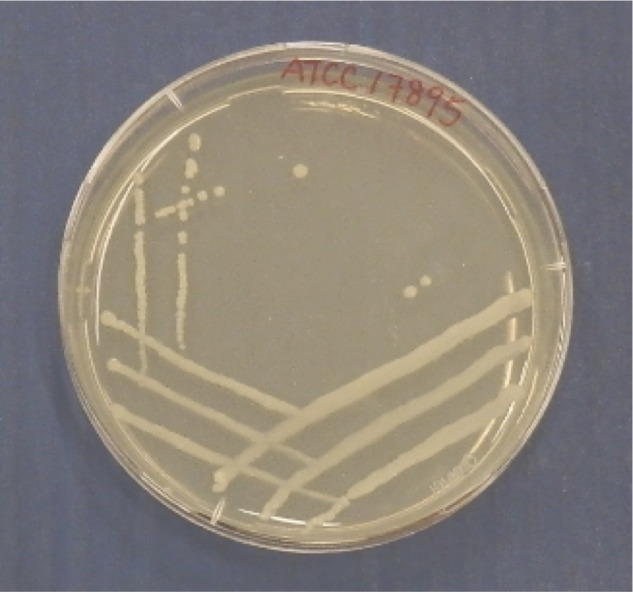

When incubated with fresh nutrient medium, R. rhodochrous grows as rod-shaped cells [20]. Furthermore cells are described to be Gram-positive actinomycetes with a pleomorphic behavior often forming a primary mycelium that soon fragments into irregular elements [21,22]. It is known to be a facultative aerobe, non-motile and may be partially acid-fast. Production of endospores or conidia has not been reported, but for some strains a few feeble aerial hyphae are observed [23,24]. The optimal growth temperature reported is 26 oC on standard culture media. After initially growing sparsely, R. rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 forms organized lumps on the agar surface, leading to the growth of dry opaque, pale orange, concentrically ringed colonies (Figure 1A and 1B). Usually growth is observed within 3 to 4 days.

Figure 1A.

Characteristic of strain ATCC 17895 on nutrient agar plate after 72 h

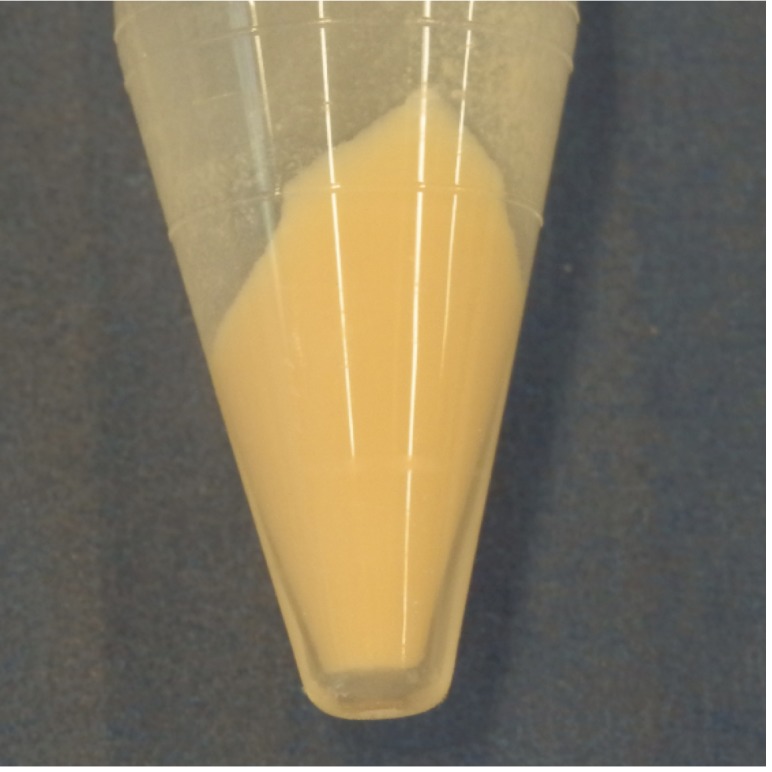

Figure 1B.

Harvested pale orange cells incubated with fresh nutrient medium after 72 h.

R. rhodochrous strains are known to produce acid from glycerol, sorbitol, sucrose and trehalose, but not from adonitol, arabinose, cellobiose, galactose, glycogen, melezitose, rhamnose or xylose. The cell wall peptidoglycan incorporates meso-diaminopimelic acid, arabinose and galactose (wall type IV) [25]. The bacterium is urease and phosphatase positive. The important characteristics of the strain based on literature descriptions are summarized in Table 1. On the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing the strain belongs to the genus Rhodococcus within class Actinobacteria, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 and Rhodococcus erythropolis strain N11 are its closest phylogenetic neighbors (Figure 2).

Table 1. Classification and general features of Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 17895 according to the MIGS recommendations [26].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Bacteria | TAS [27] | ||

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [28] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [29] | ||

| Subclass Actinobacteridae | TAS [29,30] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [29-32] | ||

| Suborder Corynebacterineae | TAS [29,30] | ||

| Family Nocardiaceae | TAS [29,30,32,33] | ||

| Genus Rhodococcus | TAS [32,34] | ||

| Species Rhododoccus rhodochrous | TAS [32,35,36] | ||

| Strain ATCC17895 | |||

| Gram stain | Positive | TAS [17] | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | TAS [20] | |

| Motility | Non-motile | TAS [17] | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | TAS [17] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | TAS [17] | |

| Optimum temperature | 26 oC | TAS [19] | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobe | TAS [17] |

| Carbon source | fructose, glucose, mannose, sucrose | TAS [17] | |

| Energy source | butyrate, fumarate, propionate | TAS [17] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Marine, Aquatic | TAS [17] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | TAS [37] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Not reported | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [19] | |

| Isolation | Pacific Ocean seawater | TAS [37] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Canada | TAS [37] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | Not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | Not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported | NAS |

Evidence codes – IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgments.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA sequence highlighting the phylogenetic position of Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain ATCC 17895 relative to other type strains within the genus Rhodococcus. Genbank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic inferences were obtained using the neighbor-joining method within the MEGA v5 software [38]. Numbers at the nodes are percentages of bootstrap values obtained by repeating the analysis 1,000 times to generate a majority consensus tree. The scale bar indicates 0.005 nucleotide change per nucleotide position.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its common use for a wide range of biotransformation, such as steroid modification, enantioselective synthesis, the production of amides from nitriles [6,39,40], and its interesting hydration capabilities [15]. The complete genome obtained in this study was sequenced in October 2012 and has been deposited at GenBank under accession number ASJJ00000000 consisting of 423 contigs (≥300 bp) and 376 scaffold (≥300 bp). The version described in this paper is version ASJJ01000000. Sequencing was performed by BaseClear BV (Leiden, the Netherlands) and initial automatic annotation by Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (Amsterdam). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Characteristic | Details |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One Illumina paired-end library, 50 cycles |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platform | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 50 × |

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Permanent draft |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | CLCbio Genomics Workbench version 5.5.1 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | RAST |

| BioProject | PRJNA201088 | |

| GenBank ID | ASJJ00000000 | |

| GenBank date of release | September 23, 2013 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | ATCC 17895 |

| Project relevance | Biotechnology |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 17895 was grown on nutrient medium [8.0 g nutrient broth (BD cat. 234000) in 1000 mL demi water] at pH 6.8 and 26 oC with orbital shaking at 180 rpm as recommended by ATCC. Extraction of chromosomal DNA was performed by using 50 mL of overnight culture, centrifuged at 4 oC and 4,000 rpm for 20 min and purified using the following method [41]. Then, 100 mg wet cells were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and washed three times with 0.5 mL potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.2). The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 564 µL Tris-HCl buffer (10 mM) containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and 10 µg lysozyme and incubated at 37 oC for 2 h. Next, Proteinase K (3 µL of 20 mg/mL stock), DNase-free RNase (2 µL of 10 mg/mL stock), SDS (50 µL of 20% w/v stock) were added and the cell suspension was incubated at 50 oC for 3 h followed by the addition of 5 M NaCl (100 µL) and incubation at 65 oC for 2 min. After addition of 80 µL of CTAB/NaCl solution (10% w/v hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide in 0.7 M NaCl) incubation at 65 oC for 10 min was performed. The cell lysate was twice extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and the aqueous layer was separated after centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. The DNA was precipitated with 0.7 volumes isopropanol and dissolved in sterile water for genome sequencing. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA was evaluated by 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis to obtain good quality DNA, with an OD260:280 ratio of 1.8-2, and as intact as possible.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic DNA libraries for the Illumina platform were generated and sequenced at BaseClear BV (Leiden, The Netherlands). High-molecular weight genomic DNA was used as input for library preparation using the Illumina TruSeq DNA library preparation kit (Illumina). Briefly, the gDNA was fragmented and subjected to end-repair, A-tailing, ligation of adaptors including sample-specific barcodes and size-selection to obtain a library with median insert-size around 300 bp. After PCR enrichment, the resultant library was checked on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and quantified. The libraries were multiplexed, clustered, and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 with paired-end 50 cycles protocol. The sequencing run was analyzed with the Illumina CASAVA pipeline (v1.8.2). The raw sequencing data produced was processed removing the sequence reads which were of too low quality (only "passing filter" reads were selected) and discarding reads containing adaptor sequences or PhiX control with an in-house filtering protocol. The quality of the FASTQ sequences was enhanced by trimming off low-quality bases using the “Trim sequences” option of the CLC Genomics Workbench version 5.5.1. The quality filtered sequence reads were puzzled into a number of contig sequences using the “De novo assembly” option of the CLC Genomics Workbench version 5.5.1. Subsequently the contigs were linked and placed into scaffolds or supercontigs with SSPACE premium software v2.3 [42]. The orientation, order and distance between the contigs were estimated using the insert size between the paired-end reads. Finally, the gapped regions within the scaffolds were (partially) closed in an automated manner using GapFiller v 1.10 [43].

Genome annotation

Genes were identified and annotated using RAST (Rapid Annotations based on Subsystem Technology) [44]. The translated CDSs were used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant (nr) database, Pfam, KEGG, and COG databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation were performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [45].

Genome properties

The genome size is around 6,869,887 bp. The G+C percentage determined from the genome sequence is 62.29%, which is similar to the value of its closest sequenced neighbor R. erythropolis PR4, determined by Sekine M [46]. The genomic information of strain PR4 was deposited to GenBank, but was not publicly available until very recent. From the genome sequence of strain ATCC 17895, there are 6,662 predicted genes, of which 6,609 are protein-coding genes, and 53 are RNA genes. A total of 5,186 genes (77.8%) are assigned a putative function. The remaining genes are annotated as either hypothetical proteins or proteins of unknown functions. The properties and statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3 and the distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4. The number and percentage of genes in different COG categories is equivalent to the closely related R. erythropolis PR4 and R. jostii RHA1, showing that most genes have been annotated, even though the genome was not fully closed.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,869,887 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 6,017,668 | 87.63 |

| DNA G + C content (bp) | 4,279,255 | 62.29 |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements (plasmid) | 0 | |

| Total genes | 6,662 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 53 | 0.80 |

| rRNA operons | 3 | 0.05 |

| Protein-coding genes | 6,609 | 99.20 |

| Pseudogenes | 0 | |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 5,469 | 82.09 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4,751 | 71.31 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 5,132 | 77.03 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 305 | 4.58 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 194 | 3.63 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 5 | 0.09 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 597 | 11.16 | Transcription |

| L | 155 | 2.90 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 42 | 0.79 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| V | 88 | 1.64 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 241 | 4.50 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 198 | 3.70 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 4 | 0.07 | Cell motility |

| U | 37 | 0.69 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 143 | 2.67 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 364 | 6.80 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 339 | 6.34 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 460 | 8.60 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 103 | 1.93 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 187 | 3.5 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 427 | 7.98 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 323 | 6.04 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 327 | 6.11 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 711 | 13.29 | General function prediction only |

| S | 404 | 7.55 | Function unknown |

| - | 1911 | 28.69 | Not in COGs |

As is obvious from Figure 2, the 16S rRNA of this R. rhodochrous strain is much closer to R. erythropolis than to R. rhodochrous. Also R. erythropolis PR4 is the closest neighbor of the currently sequenced organism. Furthermore, certain genes mentioned by Gürtler et al. to be part of R. erythropolis strains, but not to be present in R. rhodochrous [47], are all present in the genome. Therefore, as recommended by Gürtler et al., we propose that this organism should be reclassified as a strain of Rhodococcus erythroplis (Rhodococcus erythroplis ATCC 17895).

Biocatalytic properties

Since we are interested in the biocatalytic properties of this organism, we looked at enzymes known to be abundant in Rhodococcus strains. There are 27 different mono- and dioxygenases annotated in the genome, which is similar to the number in the closely related R. erythropolis PR4. And, as expected, there are 2 ureases and more than 10 phosphatases in the genome. Furthermore, there is a full nitrile metabolizing operon present, comprising nitrile hydratase, regulators, amidase and aldoxime dehydratase. Although this organism is not a catabolic powerhouse like Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 [48], which was isolated from a polluted soil, there are numerous genes coding for proteins involved in producing amino acids, cofactors and lipids. For many of these proteins there are several copies of genes with similar function. This shows the versatility of this organism, like most members of its species. The various enzymes found by this genomic annotation can be used as a starting point to exploit this organism for biocatalytic operation, for instance, the rarely investigated biocatalytic hydration [15,49], and the hydroxylation of unactivated C-H bonds [7], which remains a major challenge for synthetic chemists.

Acknowledgement

A senior research fellowship of China Scholarship Council-Delft University of Technology Joint Program to Chen B.-S. is gratefully acknowledged. Resch V thanks the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) for an “Erwin-Schroedinger” Fellowship (J3292).

References

- 1.Saeki H, Miura A, Furuhashi K, Averhoff B, Gottschalk G. Degradation of trichloroethene by a linear-plasmid-encoded alkene monooxygenase in Rhodococcus corallines ( Nocardia coralline) B-276. Microbiology 1999; 145:1721-1730 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curragh H, Flynn O, Larkin MJ, Stafford TM, Hamilton JTG, Harper DB. Haloalkane degradation and assimilation by Rhodococcus rhodochrous NCIMB 13064. Microbiology 1994; 140:1433-1442 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Leeuwen JGE, Wijma HJ, Floor RJ, van der Laan JM, Janssen DB. Directed evolution strategies for enantiocomplementary haloalkane dehalogenases: from chemical waste to enantiopure building blocks. ChemBioChem 2012; 13:137-148 10.1002/cbic.201100579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westerbeek A, van Leeuwen JGE, Szymański W, Feringa BL, Janssen DB. Haloalkane dehalogenase catalysed desymmetrisation and tandem kinetic resolution for the preparation of chiral haloalcohols. Tetrahedron 2012; 68:7645-7650 10.1016/j.tet.2012.06.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monticello DJ. Biodesulfurization and the upgrading of petroleum distillates. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2000; 11:540-546 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00154-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin MJ, Kulakov LA, Allen CCR. Biodegradation and Rhodococcus - masters of catabolic versatility. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2005; 16:282-290 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Reilly E, Aitken SJ, Grogan G, Kelly PP, Turner NJ, Flitsch SL. Regio- and stereoselective oxidation of unactivated C-H bonds with Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Beilstein J Org Chem 2012; 8:496-500 10.3762/bjoc.8.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen MS, White MC. A predictably selective aliphatic C-H oxidation reaction for complex molecule synthesis. Science 2007; 318:783-787 10.1126/science.1148597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komeda H, Hori Y, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Transcriptional regulation of the Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 nitA gene encoding a nitrilase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:10572-10577 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi M, Komeda H, Yanaka N, Nagasawa T, Yamada H. Nitrilase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1. J Biol Chem 1992; 267:20746-20751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheldon RA, Arends I, Hanefeld U. Green Chemistry and Catalysis, Wiley-VCH, 2007, p. 287-290. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada H, Kobayashi M. Nitrile hydratase and its application to industrial production of acrylamide. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1996; 60:1391-1400 10.1271/bbb.60.1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priefert H, O'Brien XM, Lessard PA, Dexter AF, Choi EE, Tomic S, Nagpal G, Cho JJ, Agosto M, Yang L, et al. Indene bioconversion by a toluene inducible dioxygenase of Rhodococcus sp I24. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2004; 65:168-176 10.1007/s00253-004-1589-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chhiba V, Bode ML, Mathiba K, Kwezi W, Brady D. Enantioselective biocatalytic hydrolysis of beta-aminonitriles to beta-amino-amides using Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC BAA-870. J Mol Catal, B Enzym 2012; 76:68-74 10.1016/j.molcatb.2011.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holland HL, Gu JX. Preparation of (R)-3-hydroxy-3-alkylbutanolides by biocatalytic hydration of 3-alkyl-2-butenolides using Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Biotechnol Lett 1998; 20:1125-1126 10.1023/A:1005320202278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finnerty WR. The biology and genetics of the genus Rhodococcus. Annu Rev Microbiol 1992; 46:193-218 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.001205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodfellow M, Alderson G. The Actinomycete-genus Rhodococcus: A home for the "rhodochrous" complex. J Gen Microbiol 1977; 100:99-122 10.1099/00221287-100-1-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haburchak DR, Jeffery B, Higbee JW, Everett ED. Infections caused by Rhodochrous. Am J Med 1978; 65:298-302 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90823-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaucamp K, Möllering H, Lang G, Gruber W, Roeschlau P. Method for the determination of cholesterol. United States Patent 1975:3925164.

- 20.Adams MM, Adams JN, Brownell GH. The identification of jensenia canicruria bisset and more as a mating type of nocardia erythropolis (gray and thornton) waksman and henrici. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1970; 20:133-147 10.1099/00207713-20-2-133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley SG, Bond JS. Taxonomic criteria for Mycobacteria and Nocardiae. Adv Appl Microbiol 1974; 18:131-190 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70571-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodfellow M, Lind A, Mordarska H, Pattyn S, Tsukamura M. A cooperative numerical-analysis of cultures considered to belong to Rhodochrous taxon. J Gen Microbiol 1974; 85:291-302 10.1099/00221287-85-2-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon RE, Mihm JM. A comparative study of some strains received as Nocardiae. J Bacteriol 1957; 73:15-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon RE. Some strains in search of a genus- Corynebacterium Mycobacterium Nocardia or What. J Gen Microbiol 1966; 43:329-343 10.1099/00221287-43-3-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowbotham TJ, Cross T. Rhodochrous-type organisms from freshwater habitats. Proc Soc Gen Microbiol 1976; 3:100-101 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The road map to the Manual, In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz R (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castellani A, Chalmers AJ. Family Nocardiaceae Manual of Tropical Medicine, Third Edition, Williams, Wood and Co., New York, 1919, p. 1040-1041. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zopf W. Über Ausscheidung von Fettfarbstoffen (Lipochromen) seitens gewisser Spaltpilze. Ber Dtsch Bot Ges 1891; 9:22-28 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsukamura M. A further numerical taxonomic study of the rhodochrous group. Jpn J Microbiol 1974; 18:37-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rainey FA, Burghardt J, Kroppenstedt R, Klatte S, Stackebrandt E. Polyphasic evidence for the transfer of Rhodococcus roseus to Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45:101-103 10.1099/00207713-45-1-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams JM, McClung NM. Comparison of the developmental cycles of some members of the genus Nocardia. J Bacteriol 1962; 84:206-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bell KS, Philp JC, Aw DWJ, Christofi N. A review - the genus Rhodococcus. J Appl Microbiol 1998; 85:195-210 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warhurst AM, Fewson CA. Biotransformations catalyzed by the genus Rhodococcus. Crit Rev Biotechnol 1994; 14:29-73 10.3109/07388559409079833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore E, Arnscheidt A, Kruger A, Strompl C, Mau M. Simplified protocols for the preparation of genomic DNA from bacterial cultures, In: Kowalchuk GA, Bruijn FJ, Head IM, Akkermans AD, Elsas van JD (eds), Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, the Netherlands, 2004, p. 3-18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 2011; 27:578-579 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boetzer M, Pirovano W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol 2012; 13:R56 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 2008; 9:75 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekine M, Tanikawa S, Omata S, Saito M, Fujisawa T, Tsukatani N, Tajima T, Sekigawa T, Kosugi H, Matsuo Y, et al. Sequence analysis of three plasmids harboured in Rhodococcus erythropolis strain PR4. Environ Microbiol 2006; 8:334-346 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gürtler V, Mayall BC, Seviour R. Can whole genome analysis refine the taxonomy of the genus Rhodococcus? FEMS Microbiol Rev 2004; 28:377-403 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLeod MP, Warren RL, Hsiao WWL, Araki N, Myhre M, Fernandes C, Miyazawa D, Wong W, Lillquist AL, Wang D, et al. The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:15582-15587 10.1073/pnas.0607048103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin J, Hanefeld U. The selective addition of water to C=C bonds; enzymes are the best chemists. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011; 47:2502-2510 10.1039/c0cc04153j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]