Significance

Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, the master regulator RpoS protects against stress, but slowed growth is the price cells pay for this protection. Under these conditions, transcription of the gene for the RpoS activator Crl increases. Strikingly, we show that this increase in transcription actually decreases Crl protein levels, thus decreasing RpoS activity and increasing growth rate. This unique regulatory mechanism has as its basis two overlapping promoters. Transcription from the promoter used under nitrogen-limitation prevents transcription of the functional crl mRNA producing instead a long noncoding RNA that has no function. Under conditions where protein synthesis is compromised, this simple, but economical mechanism causes a near-instantaneous reduction in Crl levels and RpoS activity without the need to synthesize a regulatory molecule.

Keywords: transcriptional repression, lncRNA

Abstract

RpoS (σ38) is required for cell survival under stress conditions, but it can inhibit growth if produced inappropriately and, consequently, its production and activity are elaborately regulated. Crl, a transcriptional activator that does not bind DNA, enhances RpoS activity by stimulating the interaction between RpoS and the core polymerase. The crl gene has two overlapping promoters, a housekeeping, RpoD- (σ70) dependent promoter, and an RpoN (σ54) promoter that is strongly up-regulated under nitrogen limitation. However, transcription from the RpoN promoter prevents transcription from the RpoD promoter, and the RpoN-dependent transcript lacks a ribosome-binding site. Thus, activation of the RpoN promoter produces a long noncoding RNA that silences crl gene expression simply by being made. This elegant and economical mechanism, which allows a near-instantaneous reduction in Crl synthesis without the need for transacting regulatory factors, restrains the activity of RpoS to allow faster growth under nitrogen-limiting conditions.

In Escherichia coli, RNA polymerase consists of a core, and a σ factor to provide specificity for promoter recognition. RpoD (σ70) is the housekeeping σ factor and is essential for growth (1, 2). Six other σ factors compete for core polymerase with RpoD and regulate specific genes (3). One such factor is RpoS (σ38), the general stress response σ factor (4, 5); another is RpoN (σ54), the nitrogen-stress σ factor (6).

The RpoS regulon provides defense against harsh environmental conditions, and cells that lack RpoS are highly susceptible to stress (7, 8). However, high levels of RpoS can inhibit growth (9). For example, mutants lacking RpoS grow faster on poor carbon sources like succinate (9, 10) and mutants with attenuated RpoS activity have a distinct fitness advantage known as growth advantage in stationary phase (GASP; ref. 11). Bacteria must achieve a fine balance between self-preservation and nutritional competence (SPANC; ref. 12) and for this reason, RpoS is polymorphic in wild and domesticated laboratory strains (9, 13). Not surprisingly, given the functional duality of the protein, RpoS is tightly regulated at all levels: transcription, translation, protein stability, and its activity (5). The regulatory mechanism described here regulates RpoS at yet an additional level by controlling the synthesis of an RpoS activator, Crl.

RpoS has the lowest affinity of all σ factors for core polymerase (14). One of the ways that RpoS can overcome its lack of affinity for the core polymerase is by its interaction with its activator, the prosigma factor Crl. Crl is a transcriptional activator that does not bind DNA (15), rather it biases the competition between sigma factors by stimulating the interaction between RpoS and core polymerase (16–19). Thus, Crl plays an important role in global gene regulation by enhancing RpoS activity (18, 19).

Our efforts to understand how Escherichia coli controls the activity of RpoS when protein synthesis is restricted by nitrogen limitation led to the discovery that the crl gene produces less protein despite the fact that it is transcribed at a substantially increased rate under these conditions. Unraveling this paradoxical result led to the elucidation of a completely unexpected and unique mechanism of transcriptional regulation. This mechanism has as its basis two overlapping promoters and a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). Expression of the shorter transcript blocks expression of the longer, but the former cannot be translated because it lacks a ribosome-binding site (rbs). This simple, but economical, mechanism allows a near instantaneous reduction in Crl synthesis without the need to produce any transacting regulatory factor.

Results

The Role of Crl Under Nitrogen-Stress Conditions.

In rapidly growing cells, RpoS is made but it is directed by the adaptor protein SprE (RssB) to ClpXP where, in ATP-dependent fashion, it is unfolded and rapidly degraded (15, 20, 21). Under carbon starvation conditions, ATP levels drop, proteolysis ceases, and RpoS levels increase 20-fold (22, 23). Under nitrogen-starvation conditions, ATP levels do not drop, proteolysis continues, and RpoS levels increase only twofold (22). Nonetheless, transcription from the dps promoter, which strongly depends on RpoS, increases ∼30-fold under both conditions (Fig. 1A).

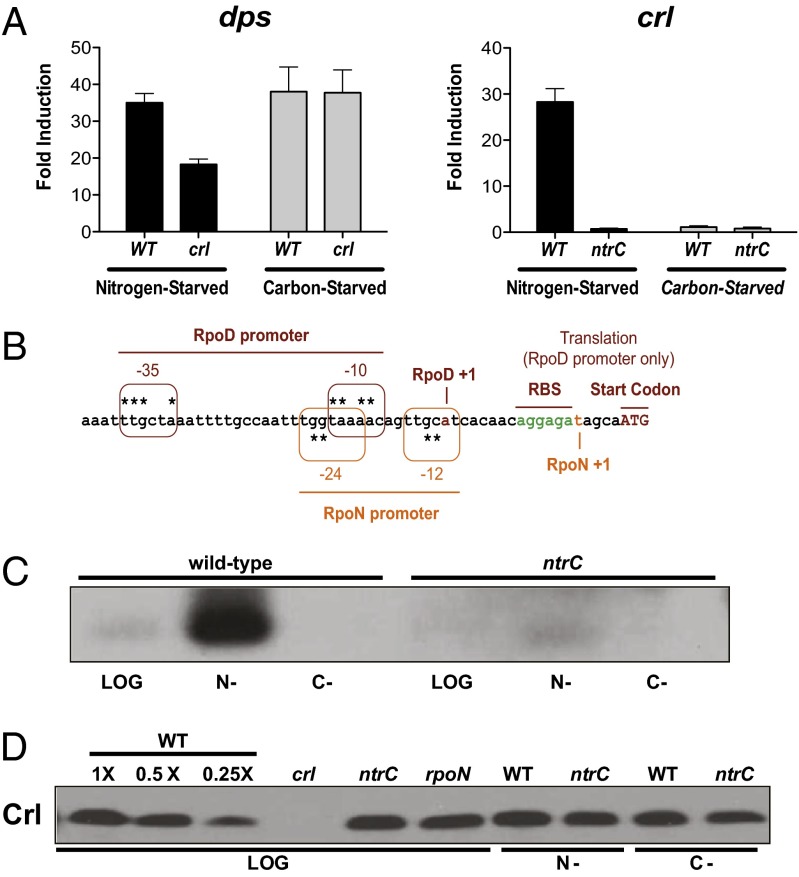

Fig. 1.

RpoS activity and crl expression under nitrogen-starvation conditions. (A) Induction of dps (Left) and crl (Right) transcription measured under carbon-starvation and nitrogen-starvation conditions relative to nonstarved cells. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) The crl promoter sequence with both RpoD and RpoN promoters are highlighted. The TSSs are indicated with a +1, and the rbs is indicated in green; asterisks mark the consensus sequence for each of the promoters. (C) Northern blot analysis of crl mRNA in wild-type and ntrC mutant strains. (D) Western analysis of Crl levels in carbon-starved (C-) or nitrogen-starved (N-) and nonstarved cells (LOG).

Because the effects of Crl on RpoS activity are greatest when RpoS levels are low (16), we wondered whether Crl might be especially important under nitrogen-starvation conditions. To test this possibility, we monitored transcription of the RpoS-dependent gene dps in the presence and absence of Crl. As shown in Fig. 1A, there is a significant reduction in dps transcription in a crl null strain under nitrogen-starvation, but not carbon-starvation, conditions. Thus, Crl plays a significant role specifically under nitrogen-starvation conditions. It should be noted that other effectors of σ factor competition, such as Rsd and 6S RNA, also contribute to dps expression under starvation conditions (Fig. S1; ref. 24).

crl Gene Expression Under Nitrogen-Starvation Conditions.

The crl gene has two functionally overlapping promoters, one that is RpoD-dependent and another that depends on RpoN (Fig. 1B). RpoN-containing polymerase always requires a transcriptional activator, a role played by nitrogen regulatory protein C (NtrC) under nitrogen-stress conditions. Because Crl has an RpoN-dependent promoter, and as it played an active role at the dps promoter under nitrogen starvation, we hypothesized that it may be up-regulated in an RpoN/NtrC-dependent manner. Indeed, there was more than a 20-fold increase in crl transcript abundance under nitrogen starvation as observed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 1A), a result confirmed by Northern blot hybridization (Fig. 1C), and this increase was abolished by removal of NtrC.

We expected that a 20-fold increase in mRNA would yield a substantial increase in Crl protein levels. Strikingly, we did not observe any change in Crl protein levels either in log phase in wild-type, rpoN, or ntrC mutant cells or in starved wild-type or ntrC mutant cells (Fig. 1D). Because Crl is a stable protein (Fig. S2), it would appear that the synthesis of Crl is not increased under these conditions.

crl Gene Expression Under Nitrogen-Limiting Conditions.

Cells starved for nitrogen stop growing quickly, thus limiting meaningful physiological experimentation. To probe the paradoxical disconnect between crl transcription and translation in more detail, we introduced a constant level of nitrogen stress by growing cells at a steady state in media containing the poor nitrogen source arginine. We denote this nitrogen-stress medium as M63 (Arg+) in contrast to the typical M63 medium that contains the preferred nitrogen source ammonia. Arginine is catabolized via the ast pathway, and expression of these genes is induced by nitrogen stress in RpoN/NtrC-dependent fashion (25, 26).

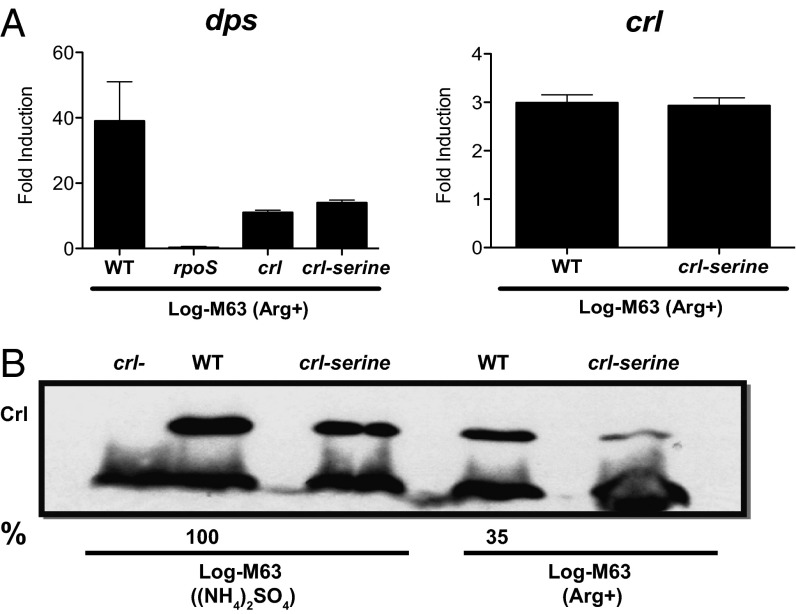

Under steady-state growth conditions in M63 (Arg+) media, dps transcription increased to a similar level (∼30-fold) as observed under nitrogen starvation. This increase completely depended on RpoS, and it was significantly lowered in strains lacking Crl (Fig. 2A). Transcription of crl was also increased, albeit more modestly, threefold (Fig. 2A), than observed under nitrogen starvation. However, under nitrogen-limiting conditions, we could measure Crl protein levels under steady-state growth conditions, a more meaningful measure of Crl protein levels than was possible with starved, nongrowing cells. Surprisingly, although crl transcript levels are increased threefold, we find that Crl protein levels are actually decreased threefold (Fig. 2B). Note that under these conditions, increased transcription of crl also is accompanied by decreased levels of Crl protein in strain MG1655, demonstrating that this surprising result is not strain specific (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

RpoS activity and crl expression under nitrogen-limiting, M63 (Arg+), conditions. (A) Induction of dps (Left) and crl (Right) transcription measured under nitrogen-limiting conditions relative to nonstarved cells. Error bars represent the SEM. (B) Western blot analysis of Crl and Crl-serine levels in nitrogen-limited and nonlimited cells. Shown is a representative of four independent experiments. Relative differences in Crl levels, as calculated by ImageJ, are shown as percentage of WT. The average difference in Crl levels between the two conditions in the WT strain is threefold.

The Role of the RpoN-Dependent crl Transcript.

As mentioned earlier, crl has two overlapping promoters (Fig. 1B): One is RpoD dependent, and the other is RpoN dependent. RpoN is known to bind to the crl promoter element (27, 28), and the transcription start sites (TSS) have been determined for both promoters. The RpoD-dependent TSS is upstream from a conserved ribosome-binding site (rbs; ref. 29), and the mRNA is translated efficiently as evidenced by the amount of Crl present in nonstressed cells (Figs. 1D and 2B). However, the RpoN-dependent TSS is further downstream and lacks an rbs (30). Transcripts that begin with the initiation codon (leaderless mRNA) are still translated, but the RpoN-dependent crl transcript has 5 bp upstream of the ATG, and such transcripts are known to be very poorly translated (31). Thus, it appears that the RpoN-dependent transcript was selected to be translated poorly, if at all, and this missing rbs likely explains the disconnect between crl mRNA and protein levels under nitrogen stress conditions. What is the purpose of the RpoN-dependent crl transcript if not to make protein?

We have considered the possibility that the crl transcript, or some part of it, functions as a regulatory RNA. Northern blot hybridizations do not detect the small differences in the RpoD- and RpoN-dependent transcripts, and they provide no evidence for RNA processing (Fig. 1C). More revealing are studies with a crl mutant in which the three cysteine codons are changed to serine (Crl-serine). This mutant gene is transcribed normally (Fig. 2A), but the mutant protein is inactive and somewhat unstable (Fig. 2B). Strains carrying this crl-serine mutant gene behave like mutants carrying a crl deletion; although the crl transcript is made at normal levels, RpoS activity is not enhanced (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the transcript has no functional relevance.

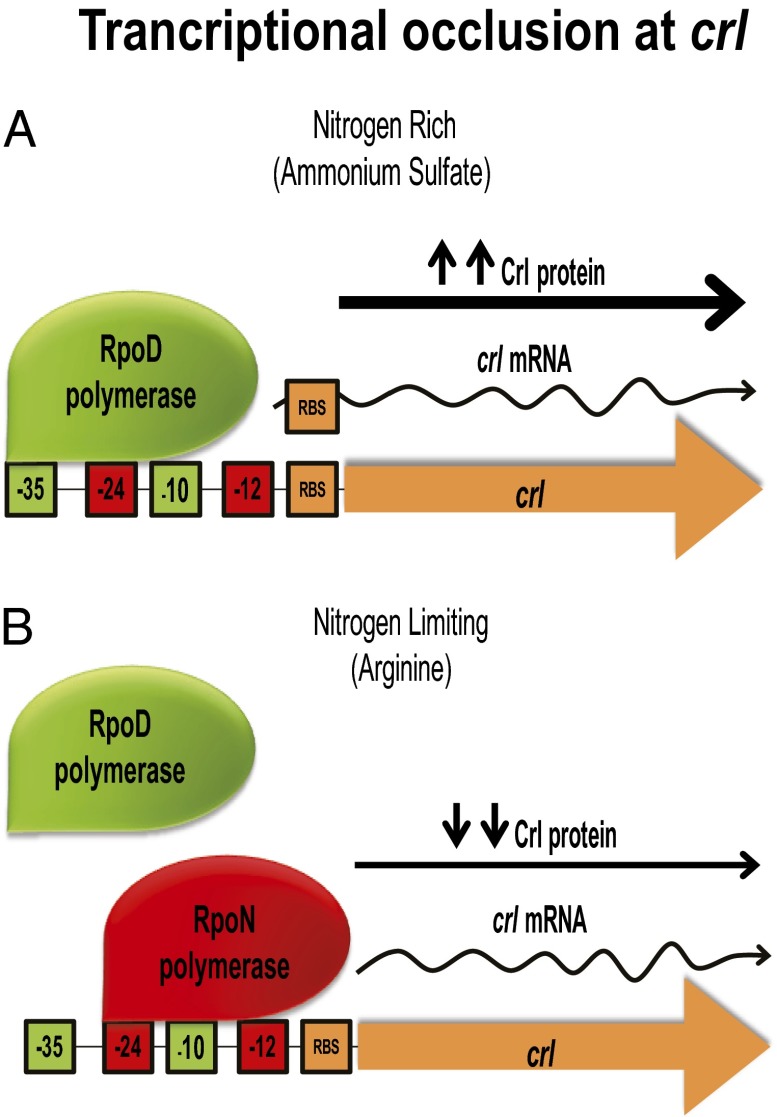

We propose instead that the RpoN polymerase has a negative regulatory role at the crl promoter functioning in a manner analogous to a traditional repressor at an RpoD-dependent promoter (Fig. 3). To test this possibility, we cloned the crl gene with its promoters and upstream elements into a low copy plasmid, pZS*11 (32). When this plasmid is introduced into a crl deletion strain, we see a fivefold increase in the crl transcript under nitrogen-limiting conditions (Fig. 4A) and a threefold decrease in Crl protein levels (Fig. 4B). Using site-directed mutagenesis, we replaced the conserved GC sequence in the -12 element of the RpoN promoter with AT (GC-12AT).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptional occlusion at crl. (A) Under nitrogen-rich conditions, the transcript made by the RpoD polymerase (green) is translated well, resulting in high Crl levels. (B) Under nitrogen-limiting conditions the RpoN polymerase (red) acts as a repressor occluding the RpoD polymerase and makes a shorter crl transcript that lacks an rbs, thus inhibiting Crl synthesis and reducing Crl levels.

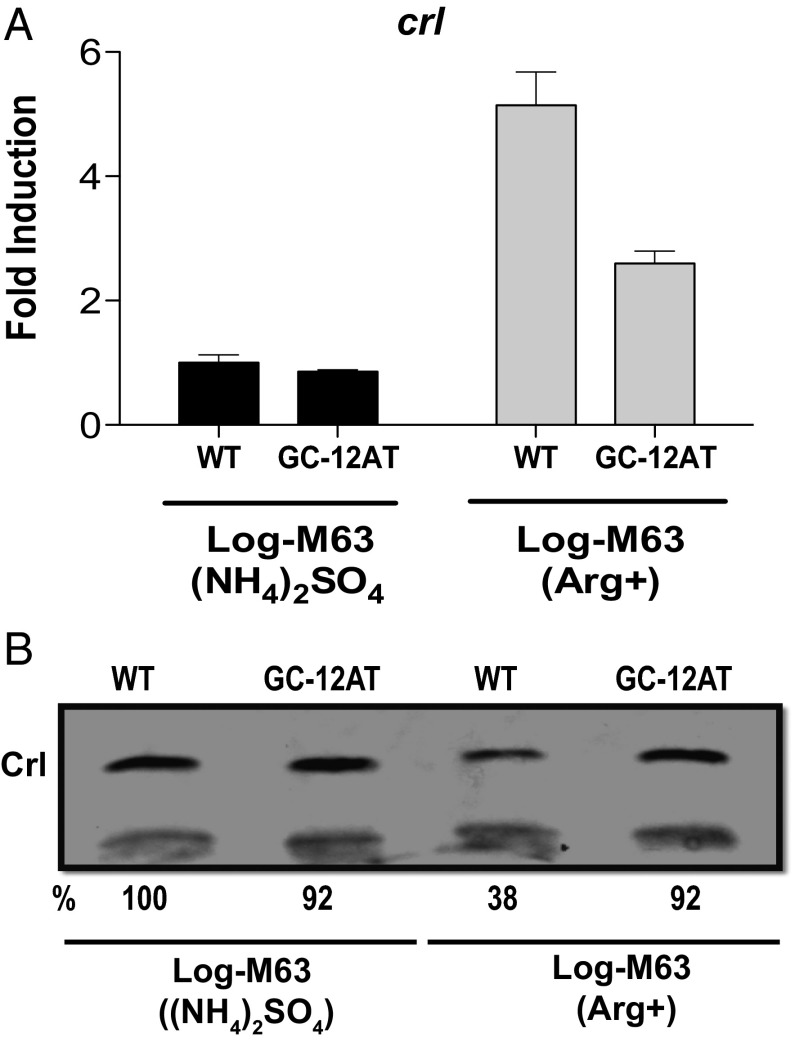

Fig. 4.

The effect of the RpoN promoter mutation GC-12AT on crl expression. (A) crl transcription was measured in exponential phase crl null strains carrying plasmid pZS*11crl-1000 with and without the GC-12AT promoter mutation. Data are presented as relative induction over cells carrying the wild-type crl plasmid grown in complete minimal media. Error bars represent the SEM. (B) Western blot analysis of Crl levels in nitrogen-limited and nonlimited cells. Shown is a representative of four independent experiments. Differences in Crl levels, as calculated by ImageJ, are shown as percentage of WT.

Although the GC-12AT change does not completely abolish the increased crl transcription seen under nitrogen-limiting conditions, it clearly reduces it (Fig. 4A). However, this decrease in transcription allows a significant increase in Crl protein levels returning them to levels similar to that seen in nonstressed cells (Fig. 4B). These results argue strongly that the RpoN polymerase itself is responsible for both the increase in crl transcription and the decrease in Crl protein levels. We suggest that the reduced occupancy of the RpoN promoter caused by the GC-12AT mutations relieves repression of the RpoD promoter, allowing for increased transcription of an mRNA with a functional rbs. The net result is an increase of Crl protein levels.

The Physiological Role of the RpoN Promoter.

The Jekyll and Hyde nature of RpoS provides a convenient way for us to test the physiological relevance of the RpoN-dependent crl promoter. RpoS is beneficial to cells growing under nitrogen-stress conditions because it protects them from a variety of different stresses. Cells lacking RpoS are far more sensitive to high temperature than are their wild-type counterparts (Fig. S4). However, this protection comes at a price. As shown in Fig. 5A, wild-type strains grow poorly in M63 (Arg+) media and under these conditions, removing RpoS improves growth dramatically.

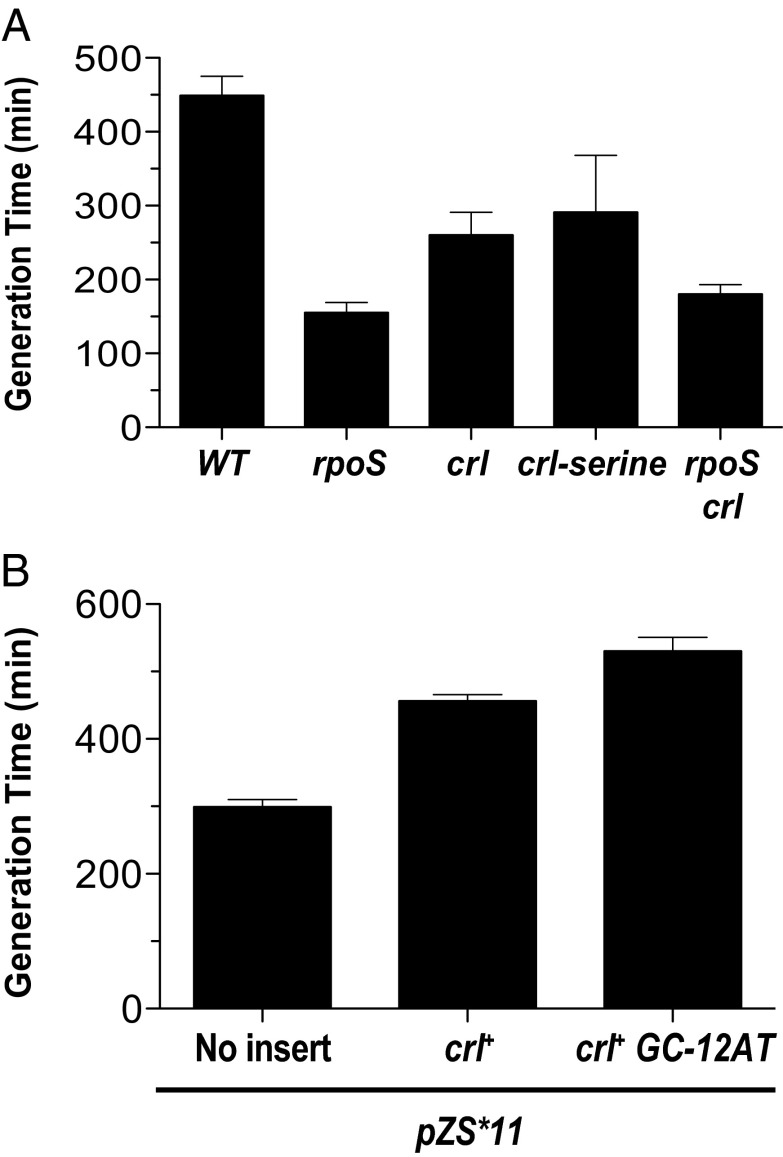

Fig. 5.

Generation times under nitrogen-limiting, M63 (Arg+), conditions. Generation time for MC4100 and rpoS::kan mutant in M63 minimal media supplemented with 0.4% glucose was determined to be ∼150 min. (A) Wild-type strains carrying the indicated mutations. (B) crl null strains carrying the indicated plasmids. Error bars represent the SEM.

Strains lacking Crl or producing the inactive Crl-serine mutant protein grow better than wild type and, as expected, the effect of removing Crl is not additive with the removal of RpoS. Fig. 5B shows that introducing the low-copy crl plasmid into strain lacking Crl slows growth. However, the same plasmid carrying the RpoN GC-12AT promoter mutation, which allows production of more Crl protein, slows growth even more: The generation time is more than 100 min longer. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, growth is inversely proportional to RpoS activity and the higher the levels of Crl, the greater the RpoS activity. When active, the RpoN promoter decreases Crl levels, thus decreasing RpoS activity and increasing growth rate.

Discussion

We have discovered a unique mechanism that regulates Crl, a regulator of RpoS, allowing precise control of the activity of this general stress response σ factor, and thus growth rate, under nitrogen-stress conditions. Our data indicate that the RpoN-dependent crl transcript, which lacks an rbs, is a lncRNA. This lncRNA has no transacting function. Rather, the RpoN polymerase that makes this lncRNA serves as a transcriptional repressor to occlude the housekeeping promoter and prevent production of the translatable crl mRNA.

A regulatory mechanism that produces an lncRNA might at first seem wasteful. However, protein synthesis requires far more energy input than does RNA synthesis (33). Moreover, in nitrogen-limited cells, where amino acids are limiting, the toll taken on cellular resources by protein synthesis becomes even greater (34–36). The transcriptional occlusion mechanism operating at crl is ideally suited for operation under these conditions. First, it is economical because it does not require the synthesis of a repressor protein. Second, it reduces Crl synthesis in near-instantaneous fashion, even faster than a transacting sRNA could act. As soon as the RpoN polymerase is activated, synthesis of the productive crl mRNA is repressed, thus further conserving valuable cellular resources.

There are many examples of regulatory, nonprotein coding RNAs in bacteria (37–40). Most bacterial regulatory RNAs are small RNAs (sRNAs) 50–150 bp in length. These sRNAs often regulate translation by base pairing with mRNAs. There are longer noncoding regulatory RNAs, such as RNAIII in several Gram-positive bacteria, which are similar in size to the crl lncRNA (∼400 bp; refs. 36 and 38). However, what makes the crl lncRNA special and different from all of these prokaryotic regulatory RNAs is functionality. Unlike these RNAs, the crl lncRNA has no transacting function.

In mammalian cells, there are many regulatory lncRNAs. Most of these eukaryotic lncRNAs function in trans to silence gene expression directly. However, for at least one of these lncRNAs, Airn, the gene silencing mechanism is different (41). Like the RpoN-dependent prokaryotic crl lncRNA, the mammalian Airn lncRNA is nonfunctional; it is the act of making these lncRNAs, not the lncRNA themselves, that is responsible for gene silencing.

The transcriptional occlusion mechanism described has as its basis overlapping promoters. At crl, the overlapping promoters produce similarly sized mRNAs, but only one of the resulting transcripts has an rbs and can be translated. There are many overlapping promoters in bacteria, and in most cases, the functional significance of this overlap is not yet known (42, 43). No other case, where one of the overlapping promoters would produce an mRNA without an rbs, has been reported. However, there may well be examples where one of the mRNAs is translated more efficiently than the other or where only one of the mRNAs is sensitive to a transacting sRNA. We suggest that the regulatory potential of promoter overlap may be largely unappreciated.

Experimental Procedures

Media and Growth Conditions.

All strains and plasmids are listed in Table S1. Standard microbial techniques were used for strain constructions. Rich media (LB) and M63 liquid medium and agar were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics as needed (44). M63 media with 0.2% arginine and 0.4% glucose was used with arginine as a sole nitrogen source. For sudden starvation, a single colony was grown overnight in 5 mL of M63 minimal media supplemented with thiamine (final concentration 100 µg/mL), MgSO4 (1 mM), and glucose (0.4%). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in M63 media and grown at 37 °C to early log-phase OD600 ∼0.3 (3 h). Cells were collected, washed three times with media lacking the appropriate carbon or nitrogen source, and finally resuspended in M63 media lacking in either carbon or nitrogen source. They were then incubated on a rotor for 1 h at 37 °C. For generation time experiments, overnight cultures in M63 media supplemented with glucose were diluted 1:100 in fresh M63 (Arg+) growth media. Cultures were grown at 37 °C. Aliquots were removed at 10-, 14-, 16-, and 20-h time interval and plated on LB plates to determine CFUs. For reference, the generation time for MC4100 in M63 media with glucose is approximately 150 min.

Plasmid Construction.

For construction of pZS*11crl-1000 (low copy 3–5 copies per cell), colony PCR was performed on MC4100 cells with primers that amplify the crl ORF and 1,000 bases upstream of the Crl ATG, so that the plasmid construct had native crl promoter, activator, and ribosomal binding site present. The primers pZS-XbaI-crl-1000upstream and pZS-KpnI-Crl-c-terminal were used for cloning (Table S2). The crl construct was put in reverse orientation so that expression was only driven by the crl promoter and not by the tet promoter. After digestion with KpnI and XbaI, the resulting PCR product was ligated into the KpnI and XbaI sites of pZS*11 (32). Constructs were sequenced by Genewiz with primer Crl-200F.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Plasmids were mutagenized by using the Gene Tailor Site-Directed Mutagenesis system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The GC-12AT was introduced into the plasmid pZS*11crl-1000 by using primers Crl(+)gc-AT and Crl(-)gc-AT. Mutagenized plasmids were transformed into DH5α. Plasmids were extracted by using Qiagen plasmid kit as per manufacturers’ instructions and sequenced by Genewiz using primer Crl-200F.

λ Red-Mediated Recombination for Strain Construction.

Recombination using a single-stranded oligonucleotide was carried out as described (45). To construct the crlC28S C37S C41S allele (MJM372), the oligo (MJM335ss) was used. RFLP analyses were carried out for loss of an HpyCH4V site at codon 28.

qRT-PCR.

The qRT-PCR assay was carried out as described (46). Five microliters of the 1×, 0.1×, or 0.01× concentrations of cDNA for standards and 5 μL of 0.1× for all other samples were added to MicroAmp Optical 96-well reaction plates. SYBR Green PCR master mix supplied by Applied Biosystems was used in each reaction. Samples were run on an ABI Prism 7900 HT real-time PCR system, and data was analyzed (standard curve method) by using SDS software (v.2.1, Applied Biosystems). The ompA transcript was used as an internal control to adjust for differing amounts of input cDNA. All reactions were run in triplicates, and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

We examined the expression of a number of genes in the RpoS regulon that are induced under nitrogen-starvation or nitrogen-limiting conditions, including bolA, tktB, osmY, poxB, and dps. We show results with dps because its induction was most strongly dependent on RpoS (Fig. 2A).

Gel Electrophoresis and Analyses.

Western and Northern blot analyses were performed as described (22, 47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

T.J.S. and coworkers are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Science Grant GM065216.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1323413111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Paget M, Helmann J. The σ70 family of sigma factors. Genome Biol. 2003;4(203):1–6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-1-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooney RA, Darst SA, Landick R. Sigma and RNA polymerase: An on-again, off-again relationship? Mol Cell. 2005;20(3):335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyström T. Growth versus maintenance: A trade-off dictated by RNA polymerase availability and sigma factor competition? Mol Microbiol. 2004;54(4):855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong T, Schellhorn HE. Control of RpoS in global gene expression of Escherichia coli in minimal media. Mol Genet Genomics. 2009;281(1):19–33. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battesti A, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitzer L. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengge-Aronis R. Survival of hunger and stress: The role of rpoS in early stationary phase gene regulation in E. coli. Cell. 1993;72(2):165–168. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90655-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Notley-McRobb L, King T, Ferenci T. rpoS mutations and loss of general stress resistance in Escherichia coli populations as a consequence of conflict between competing stress responses. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(3):806–811. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.806-811.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King T, Ishihama A, Kori A, Ferenci T. A regulatory trade-off as a source of strain variation in the species Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(17):5614–5620. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5614-5620.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang SM, Dong T, Edge TA, Schellhorn HE. Phenotypic diversity caused by differential RpoS activity among environmental Escherichia coli isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(22):7915–7923. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05274-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zambrano MM, Siegele DA, Almirón M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science. 1993;259(5102):1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferenci T. Maintaining a healthy SPANC balance through regulatory and mutational adaptation. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atlung T, Nielsen HV, Hansen FG. Characterisation of the allelic variation in the rpoS gene in thirteen K12 and six other non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002;266(5):873–881. doi: 10.1007/s00438-001-0610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda H, Fujita N, Ishihama A. Competition among seven Escherichia coli sigma subunits: Relative binding affinities to the core RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(18):3497–3503. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pratt LA, Silhavy TJ. Crl stimulates RpoS activity during stationary phase. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29(5):1225–1236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal T, Mandel MJ, Silhavy TJ, Gourse RL. Crl facilitates RNA polymerase holoenzyme formation. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(22):7966–7970. doi: 10.1128/JB.01266-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bougdour A, Lelong C, Geiselmann J. Crl, a low temperature-induced protein in Escherichia coli that binds directly to the stationary phase sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(19):19540–19550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lelong C, et al. The Crl-RpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(4):648–659. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600191-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England P, et al. Binding of the unorthodox transcription activator, Crl, to the components of the transcription machinery. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(48):33455–33464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807380200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muffler A, Fischer D, Altuvia S, Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the sigma(S) subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15(6):1333–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Gottesman S, Hoskins JR, Maurizi MR, Wickner S. The RssB response regulator directly targets sigma(S) for degradation by ClpXP. Genes Dev. 2001;15(5):627–637. doi: 10.1101/gad.864401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandel MJ, Silhavy TJ. Starvation for different nutrients in Escherichia coli results in differential modulation of RpoS levels and stability. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(2):434–442. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.434-442.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson CN, Levchenko I, Rabinowitz JD, Baker TA, Silhavy TJ. RpoS proteolysis is controlled directly by ATP levels in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2012;26(6):548–553. doi: 10.1101/gad.183517.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bougdour A, Cunning C, Baptiste PJ, Elliott T, Gottesman S. Multiple pathways for regulation of σS (RpoS) stability in Escherichia coli via the action of multiple anti-adaptors. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(2):298–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider BL, Kiupakis AK, Reitzer LJ. Arginine catabolism and the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(16):4278–4286. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4278-4286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiupakis AK, Reitzer LJ. ArgR-independent induction and ArgR-dependent superinduction of the astCADBE operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(11):2940–2950. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2940-2950.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaslaver A, et al. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat Methods. 2006;3(8):623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao K, Liu M, Burgess RR. Promoter and regulon analysis of nitrogen assimilation factor, sigma54, reveal alternative strategy for E. coli MG1655 flagellar biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1273–1283. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendoza-Vargas A, et al. Genome-wide identification of transcription start sites, promoters and transcription factor binding sites in E. coli. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10):e7526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. Compilation and analysis of sigma(54)-dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(22):4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Udagawa T, Shimizu Y, Ueda T. Evidence for the translation initiation of leaderless mRNAs by the intact 70 S ribosome without its dissociation into subunits in eubacteria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(10):8539–8546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutz R, Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(6):1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neidhardt F, Ingraham J, Schaechter M. Physiology of the Bacterial Cell: A Molecular Approach. Sunderland, MA.: Sunauer Associates; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleiner D. Bacterial ammonium transport. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;32:87–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleiner D. Energy expenditure for cyclic retention of NH3/NH4+ during N2 fixation by Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEBS Lett. 1985;187(2):237–239. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neijssel OM, Buurman ET, Teixeira de Mattos MJ. The role of futile cycles in the energetics of bacterial growth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1018(2-3):252–255. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90260-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tegmark K, Morfeldt E, Arvidson S. Regulation of agr-dependent virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus by RNAIII from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(12):3181–3186. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3181-3186.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janzon L, Arvidson S. The role of the delta-lysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 1990;9(5):1391–1399. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westhof E. The amazing world of bacterial structured RNAs. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):108. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Lay N, Schu DJ, Gottesman S. Bacterial small RNA-based negative regulation: Hfq and its accomplices. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(12):7996–8003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.441386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latos PA, et al. Airn transcriptional overlap, but not its lncRNA products, induces imprinted Igf2r silencing. Science. 2012;338(6113):1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1228110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salgado H, et al. RegulonDB (version 4.0): Transcriptional regulation, operon organization and growth conditions in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D303–D306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shearwin KE, Callen BP, Egan JB. Transcriptional interference—a crash course. Trends Genet. 2005;21(6):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silhavy TJ, Berman ML, Enquist LW. Experiments with Gene Fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costantino N, Court DL. Enhanced levels of lambda Red-mediated recombinants in mismatch repair mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(26):15748–15753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434959100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malinverni JC, Silhavy TJ. An ABC transport system that maintains lipid asymmetry in the gram-negative outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(19):8009–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin M, Showalter R, Silverman M. Identification of a locus controlling expression of luminescence genes in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(5):2406–2414. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2406-2414.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.