Significance

Childhood and youth obesity represent significant US public health challenges. Recent findings that the childhood obesity ‘‘epidemic’’ may have slightly abated have been met with relief from health professionals and popular media. However, we document that the overall trend in youth obesity rates masks a significant and growing class gap between youth from upper and lower socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. Until 2002, obesity rates increased at similar rates for all adolescents, but since then, obesity has begun to decline among higher SES youth but continued to increase among lower SES youth. These results underscore the need to target public health interventions to disadvantaged youth who remain at risk, as well as to examine how health information circulates through class-biased channels.

Keywords: social inequality, overweight, health disparities, social class, public policy

Abstract

Recent reports suggest that the rapid growth in youth obesity seen in the 1980s and 1990s has plateaued. We examine changes in obesity among US adolescents aged 12–17 y by socioeconomic background using data from two nationally representative health surveys, the 1988–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys and the 2003–2011 National Survey of Children’s Health. Although the overall obesity prevalence stabilized, this trend masks a growing socioeconomic gradient: The prevalence of obesity among high-socioeconomic status adolescents has decreased in recent years, whereas the prevalence of obesity among their low-socioeconomic status peers has continued to increase. Additional analyses suggest that socioeconomic differences in the levels of physical activity, as well as differences in calorie intake, may have contributed to the growing obesity gradient.

Childhood and adolescent obesity is one of the most important current public health concerns in the United States. The prevalence of obesity among adolescents has more than doubled over the past three decades (1). Recent data from the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that more than one-third of adults and almost 17% of children and adolescents were obese. Obesity in children and adolescents increases the risk for a variety of adverse health outcomes, including type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and various psychosocial problems (2–6).

Recent research suggests that the tide might be turning, however. After years of steady increase, obesity rates have finally begun to plateau (7). Furthermore, American children consumed fewer calories in 2010 than they did a decade before (8). For boys aged 2–19 y, calorie consumption declined by about 7% to 2,100 calories a day over the period of the analysis, from 1999 through 2010. For girls, it dropped by 4% to 1,755 calories a day. Another recent study found that teenagers are exercising more, consuming less sugar, and eating more fruits and vegetables (9).

Some health experts have taken these findings as a sign that the obesity epidemic might finally be abating. According to a recent report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), obesity rates among low-income preschoolers modestly declined in 19 US states and territories between 2008 and 2011 (10). However, there are compelling reasons to suspect that this abatement may not be equally distributed across youth from different class backgrounds. Socioeconomic background influences an individual’s food consumption and physical activity patterns. Not only are fresh vegetables and fruits costlier than fast food, but healthy alternatives are sometimes hard to find in poor neighborhoods. According to a recent estimate by the US Department of Agriculture, 9.7% of the US population, or 29.7 million people, live in low-income areas more than one mile from a supermarket, where the only options for grocery shopping are “convenience” stores, liquor stores, gas stations, or fast food restaurants that sell foods high in fat, sugar, and salt (11). Low-income families are less likely to own a car, and may thus opt for diets that are shelf-stable (12). Dry packaged foods have a long shelf life, but they also contain refined grains, added sugars, and added fats. Neighborhoods influence not only food access but opportunities for physical activity. Low-income neighborhoods have fewer playgrounds, sidewalks, and recreational facilities (13). Education is linked to both understanding what healthy diet and healthy lifestyle mean as well as how to implement them (14). Children of more educated parents are more likely to eat breakfast and consume fewer calories from snacks, and they are less likely to eat foods with high-energy content, such as sweetened beverages (15).

Although substantial socioeconomic inequalities in childhood and adolescent obesity are well documented, there is no consensus on the extent to which social disparities in obesity have changed over time. Indeed, some studies have suggested that socioeconomic gaps in the prevalence of obesity among youth have increased (16–19), whereas other research has suggested that disparities have not changed (20) or have even decreased (21, 22). To address this question, we examined socioeconomic disparities in the prevalence of obesity among adolescents aged 12–17 y using data from two large, nationally representative federal health surveys, the 1988–2010 NHANES and the 2003–2011 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

Results

Prevalence of Adolescent Obesity.

The national prevalence of obesity among adolescents aged 12–17 y increased from 9.1% [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.7–10.5] in 1988–1991 to 17.0% (95% CI: 14.7–19.2) in 2003–2004. There was no change in obesity prevalence between 2003–2004 and 2009–2010, however, suggesting that the rapid increases in obesity seen in the 1980s and 1990s are leveling off. Our analysis suggests that this encouraging trend might be masking growing socioeconomic disparities. [Consistent with prior research using NHANES data, we do not find significant differences in obesity prevalence by family income or education among children aged 2–5 y or 6–11 y (22)].

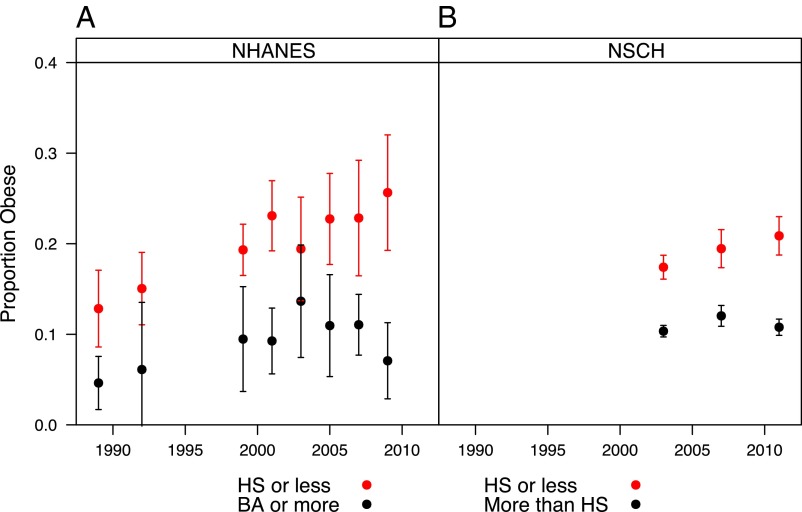

Fig. 1 shows clear differences in obesity prevalence among adolescents by parental education in both surveys. In the NHANES (Fig. 1A), a growing gap appears to reemerge beginning with the 2007–2008 data collection period. Furthermore, the class-specific trends in obesity prevalence appear to diverge beginning with the 2003–2004 period: The point estimates for children of parents who have at most a high school degree increase, whereas the point estimates for children of parents who have at least a 4-y college degree begin to decline. The fact that we find a similar and more precisely estimated pattern and timing of the growing class gaps in the NSCH data (Fig. 1B) provides corroborating evidence. We find similar trends when we use a measure of family income instead of parental education to measure socioeconomic status (SES) (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Trends in obesity among adolescents aged 12–17 y by parental education in the NHANES III (1999–2010) (A) and the NSCH (2003, 2007, and 2011). (B) Obesity is defined as being at or above the sex- and age-specific 95th percentile of the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. BA, bachelor's degree; HS, high school.

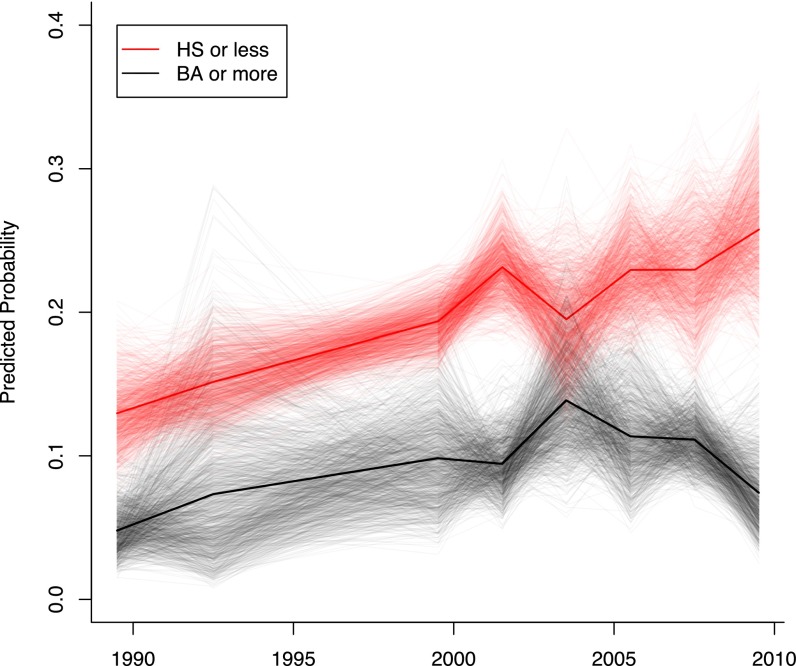

We test the robustness of these findings via a series of simulations, a subset of which is shown in Fig. 2 (details are provided in SI Text). Based on the entire set of simulated values, we calculated the proportion of simulations in which the class gap increased, the prevalence of obesity declined among children of highly educated parents, and the prevalence of obesity for children of less educated parents increased for each pair of surveys between 2003–2004 and 2009–2010 (Table S1). Except for the comparisons between 2007–2008 and 2005–2006, we find support for growing class gaps in the prevalence of obesity, especially considering the small cell sizes upon which these estimates are based and the short period between surveys. The 2009–2010 class gap was larger than the 2003–2004 class gap in more than 97% of the simulations.

Fig. 2.

Visualizing uncertainty in the obesity gap among adolescents aged 12–17 y in the NHANES III (1999–2010). The narrow lines are based on 1,000 simulated trends, and the dark lines are the means of the simulated trend estimates.

Turning to the direction of the class-specific trends, we see that across the final four NHANES, the prevalence of obesity among children of college graduates declined in more than 95% of the simulations, whereas the prevalence of obesity among children whose parents have at most a high school diploma increased in more than 92% of the simulations (Fig. S2, simulations are based on NSCH data).

We also tested the robustness of these findings by looking at the class-specific trends within race-ethnic groups. The divergence was even greater among non-Hispanic whites than it was for the entire sample (Fig. S3). Although the number of high SES adolescents among nonwhite ethnic groups was too small to derive conclusive evidence, we failed to find statistically significant differences between non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and adolescents from other race-ethnic groups and their non-Hispanic white peers. (Within race-ethnic group analyses are available from the authors upon request.) Since the growing class gap appears robustly when we confine the analysis to whites only, the growing gap itself does not spuriously reflect race-ethnic differences. The available national samples are too small to explore race-class interactions or to determine reliably whether the growing class gap also appears among non-white adolescents taken alone.

Potential Explanations for the Growing Gap.

Excessive food intake is a major contributor to obesity. Another large contributor to high rates of childhood obesity is lack of physical activity (23). Children who routinely participate in sports or activities outside of school or who walk or bike to school are less likely to be overweight or obese compared with children who do not participate in free-time physical activity and are driven to school (24). Consequently, to provide further insight into factors that contribute to childhood obesity, we examine class disparities in behaviors related to energy intake and physical activity.

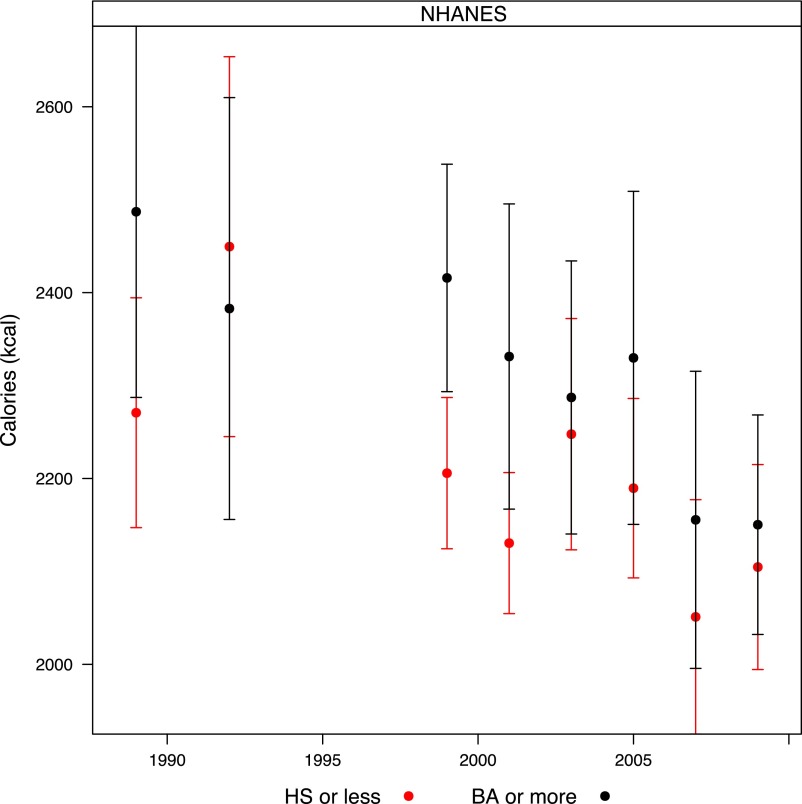

Figs. 3 and 4 plot the trends in caloric intake and physical activity, respectively (also see Table S2). Average daily energy intake decreased over this 12-y period among all children. However, energy intake fell more among high SES children: The average energy intake for adolescents with college-educated parents decreased from 2,487 (95% CI: 2,287–2,687) kilocalories in 1988–1991 to 2,150 (95% CI: 2,032–2,268) kilocalories in 2009–2010. In contrast, the average energy intake for adolescents with high school-educated parents decreased from 2,271 (95% CI: 2,147–2,394) kilocalories in 1989–1991 to 2,105 (95% CI: 1,994–2,215) kilocalories in 2009–2010.

Fig. 3.

Trends in daily caloric intake among adolescents aged 12–17 y by parental education in the NHANES III (1999–2010). Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

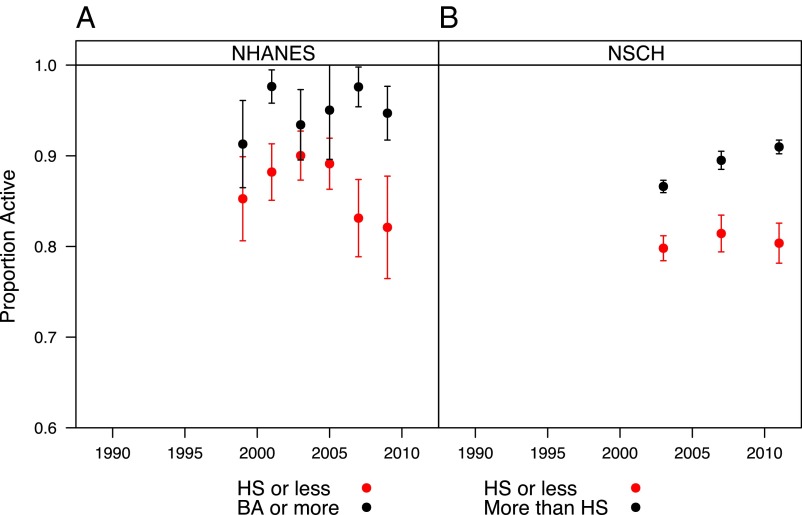

Fig. 4.

Trends in adolescent physical activity by parental education in the NHANES (1999–2010) (A) and the NSCH (2003, 2007, and 2011) (B) In the NHANES, physical activity is defined as at least 10 min in the past 30 d. In the NSCH, it is defined as at least 20 min in the past 7 d. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Fig. 4 shows a clear socioeconomic disparity in physical activity in both the NHANES and NSCH. In 2003, 93.4% (95% CI: 89.5–97.3) of adolescents with college-educated parents reported at least 10 min of continuous physical activity in the past 30 d and 86.6% (95% CI: 85.9–87.3) reported having exercised or played a sport for 20 min or more at least once in the past 7 d. In contrast, adolescents with high school-educated parents reported significantly lower levels of physical participation: 90.0% (95% CI: 87.3–92.7) reported at least 10 min of physical activity in the past 30 d, and 79.8% (95% CI: 78.4–81.2) reported having exercised or played a sport for 20 min or more at least once in the past 7 d.

In the most recent wave of each survey, there is a significant increase in disparities in physical activity. In 2009–2010, 94.7% (95% CI: 91.7–97.7) of adolescents with college-educated parents reported some physical activity in the past 30 d compared with only 82.1% (95% CI: 76.5–87.8) of adolescents with high school-educated parents. In 2011, 91% (95% CI: 90.2–91.7) of adolescents whose parents have at least some college education reported at least 20 min of activity in the past week compared with 80.4% (95% CI: 78.2–82.6) whose parents have a high school education or less. In short, in 2003, the class gap in physical activity was 3 to 7 percentage points, whereas in 2009–2011, the comparable class gap was 11 to 13 percentage points.

Discussion

Childhood obesity is associated with increased health risks and decreased quality of life, as well as declining adult health and greater health care costs. In response, national and state health policies are being developed and adopted across a variety of sectors to reduce the burden of childhood obesity. Health care professionals, schools, and advocacy organizations are now engaged in efforts to prevent and reduce childhood overweight and obesity. On the surface, at least, these efforts have not been in vain. After years of steady increase, obesity rates have finally begun to level off (7, 10). Overall, children are consuming fewer calories today than they did a decade ago, and fewer of their calories are coming from carbohydrates (8, 9). The consumption of fast food has also declined (25). Children are also more physically active than they were a decade ago (9).

However, the public health message has not diffused evenly across the population. We find that although the overall obesity prevalence has plateaued, the trend looks very different across different subgroups. The prevalence of obesity among adolescents of well-educated families has decreased in recent years, whereas the prevalence of obesity among their peers in less educated families has continued to increase. To design effective interventions, it is important to understand how different populations vary in the health behaviors that lead to obesity.

The obesity epidemic is a complex public health problem, but in its simplest form, obesity results from an energy imbalance where caloric intake exceeds the calories expended by physical activity and metabolic processes: We take in more calories that we expend. This seemingly simple imbalance has many underlying causes: Obesity reflects complex interactions among genetic, metabolic, behavioral, cultural, and environmental factors. Behavioral factors include sedentary lifestyles and consumption of excess calories and reflect environmental factors that influence behaviors, and thus energy intake and energy output. The physical environment can encourage or discourage physical activity, and the availability of food can encourage or discourage a healthy diet. In addition, there is both quantitative and qualitative evidence that social networks and community ties influence eating and activity behaviors (26–28).

Increases in the prevalence of obesity have often been linked to increases in unhealthy eating habits, such as the consumption of refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverages. In the 1980s and 1990s, the consumption of carbohydrates increased rapidly in the United States. In 1994–1996, more than one-third of carbohydrates consumed by adults and children above the age of 2 y came from caloric sweeteners, such as soft drinks (29). Increases in the consumption of junk food and increased portion size of fast food have been linked to increasing body weight (30). Consequently, reducing the consumption of high-energy, low-nutrition food has been the focus of many public health programs. The effort is paying off: We find that children from all socioeconomic backgrounds consumed fewer calories in 2010 than they did a decade before.

Despite these healthy changes in energy consumption, some children continue to gain weight. Our findings suggest that increasing health disparities stem from growing differences in both calorie intake and physical activity. Although the average energy intake has decreased among all children, it has fallen more among children from wealthy, educated homes. Many children live a sedentary lifestyle that makes it difficult for them to expend enough calories to make up for what they consume. In 2002, three-fifths of children between the ages of 9 and 13 y did not participate in any organized physical activity outside of school hours and almost a quarter failed to engage in any physical activity during their free time (31). Moreover, there is an increasing class gradient in physical activity. We find that children of college-educated parents not only consume fewer calories than they did a decade before but that they are physically more active than they were before. Children of less educated parents, however, did not experience a similar increase in physical activity. This could be because many low SES children live in environments that do not facilitate a physically active lifestyle. The lack of community recreational centers, playgrounds, or sidewalks and concerns for safety when outdoors can stand in the way of children being physically active (32, 33). However, although neighborhood constraints may contribute to differences in physical activity, this is not the full story: Participation in high school sports and clubs has increased among high SES adolescents while decreasing among their low SES peers.*

Eliminating socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes is a key public policy priority. In recent years, many national initiatives, such as the Let’s Move initiative, and recommendations from the American Public Health Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Institute of Medicine have built awareness around childhood obesity. Our findings indicate that health inequalities related to obesity are increasing and that the social determinants of obesity are complex. More research is needed to help understand the underlying causes of the disparities. In addition, future research on the health and economic consequences of childhood obesity is needed, both in the whole population and in subgroups. More vigorous government support and targeted programs are needed to fight the epidemic, reduce the disparities in physical activity, and prepare the nation to face the related future consequences. Eating behaviors and lifestyles established in childhood often track into later life. If a boy is overweight at the age of 16 y, he will have an 80% likelihood of remaining obese as an adult (92% for girls) (34). Thus, effective intervention programs to promote healthy lifestyles among young people (especially among lower SES youth) will not only aid in the fight against the youth obesity epidemic but will help prevent other chronic diseases, reduce future health care costs, and pave the way for a healthier nation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert M. Axelrod, Harvey Fineberg, and Christopher Murray for helpful discussions during the early stages of this project and Thomas Sander, Jennifer M. Silva, Chaeyoon Lim, and Catherine Womack for comments on this manuscript. We also thank the reviewers, Elsie M. Taveras, Matthew W. Gillman, and Ross Hammond, for their comments and suggestions. For support of our larger research project on inequality, we thank the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Ford Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Markle Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and the Spencer Foundation. We also thank the INSEAD Alumni Fund (IAF) for support of this project.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Frederick C, Snellman K, Putnam R (2013) Growing class differences in youth civic engagement. American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, August 9, 2013, New York.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1321355110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels SR, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: Pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. 2005;111(15):1999–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright CM, Parker L, Lamont D, Craft AW. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: Findings from thousand families cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323(7324):1280–1284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: Childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360(9331):473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Waters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. JAMA. 2005;293(1):70–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ogden C, Carroll M, Kit BK, Flegal K (2012) Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No 82. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD.

- 8. Ervin RB, Ogden CL (2013) Trends in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients in Children and Adolescents from 1999–2000 Through 2009–2010. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No 113. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed]

- 9.Iannotti RJ, Wang J. Trends in physical activity, sedentary behavior, diet, and BMI among us adolescents, 2001-2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):606–614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: Obesity among low-income, preschool-aged children—United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(31):629–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ver Ploeg M, et al. (2012) Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Updated Estimates of Distance to Supermarkets using 2010 Data. ERR-143 (US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Washington, DC)

- 12.Drewnowski A. Energy density, palatability, and satiety: Implications for weight control. Nutr Rev. 1998;56(12):347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughan KB, et al. Exploring the distribution of park availability, features, and quality across Kansas City, Missouri by income and race/ethnicity: An environmental justice investigation. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(Suppl 1):S28–S38. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9425-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardle J, Parmenter K, Waller J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite. 2000;34(3):269–275. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Family income and education were related with 30-year time trends in dietary and meal behaviors of American children and adolescents. J Nutr. 2013;143(5):690–700. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.165258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bethell C, Simpson L, Stumbo S, Carle AC, Gombojav N. National, state, and local disparities in childhood obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):347–356. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miech RA, et al. Trends in the association of poverty with overweight among US adolescents, 1971-2004. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2385–2393. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Rising social inequalities in US childhood obesity, 2003-2007. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(1):40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen X, et al. Decreasing prevalence of obesity among young children in Massachusetts from 2004 to 2008. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):823–831. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Measuring health disparities: Trends in racial-ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in obesity among 2- to 18-year old youth in the United States, 2001-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(10):698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Using concentration index to study changes in socio-economic inequality of overweight among US adolescents between 1971 and 2002. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):916–925. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y. Disparities in pediatric obesity in the United States. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(1):23–31. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick K, et al. Diet, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors as risk factors for overweight in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drake KM, et al. Influence of sports, physical education, and active commuting to school on adolescent weight status. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e296–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fryar CD, Ervin RB (2013) Caloric Intake from Fast Food Among Adults: United States, 2007-2010. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No 114. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD.

- 26.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulvaney-Day N, Womack C. Obesity, identity and community: Leveraging social networks for behavior change in public health. Public Health Ethics. 2009;2(3):250–260. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman L, Karpati A. Understanding the sociocultural roots of childhood obesity: Food practices among Latino families of Bushwick, Brooklyn. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(11):2177–2188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popkin BM, Nielsen SJ. The sweetening of the world’s diet. Obes Res. 2003;11(11):1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. ed 7. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Physical activity levels among children aged 9-13 years—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(33):785–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Relative influences of individual, social environmental, and physical environmental correlates of walking. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1583–1589. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang LY, Chyen D, Lee S, Lowry R. The association between body mass index in adolescence and obesity in adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.