Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with obesity, a major risk factor for a number of chronic illnesses (e.g., cardiovascular disease). We examined whether impulsivity and affective instability mediate the association between BPD pathology and body mass index (BMI). Participants were a community sample of adults ages 55–64 and their informants. The Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality measured BPD symptoms and the Revised NEO Personality Inventory measured self- and informant-report impulsivity and affective instability. Mediation analyses demonstrated that only higher self-report impulsivity significantly mediated the association between greater BPD pathology and higher BMI. A subsequent model revealed that higher scores on the impulsiveness (lack of inhibitory control) and deliberation (planning) facets of impulsivity mediated the BPD–BMI association, with impulsiveness exerting a stronger mediation effect than deliberation. Obesity interventions that improve inhibitory control may be most effective for individuals with BPD pathology.

Keywords: Borderline personality disorder, Personality pathology, Obesity, Body mass index, Impulsivity, Inhibitory control, Affective instability, Emotion dysregulation

1. Introduction

A large body of evidence shows that personality predicts important health outcomes (e.g., mortality, blood pressure, health perceptions) (Mroczek & Spiro, 2007; Powers & Oltmanns, 2012; Turiano et al., 2012). As such, researchers have become increasingly interested in identifying the affective and behavioral mechanisms by which personality processes impact health. Borderline personality disorder (BPD), characterized by pervasive emotional and behavioral dysregulation, is associated with elevated risk for chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, and hypertension, above and beyond the risk afforded by general personality pathology (El-Gabalawy, Katz, & Sareen, 2010; Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Curtin, 2010; Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2011; Powers & Oltmanns, 2012, 2013). Obesity is also associated with BPD and is a major risk factor for a number of these illnesses (e.g., type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease) (Flegal et al., 2010; Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2004, 2006, 2011; Powers & Oltmanns, 2013; Sansone, Wiederman, & Monteith, 2001).

Obesity is influenced by behavioral processes associated with personality (e.g., disinhibited eating) (Elfhag & Morey, 2008; Mobbs, Ghisletta, & Van der Linden, 2008; Provencher et al., 2008), and thus may play an important role in the association between BPD and chronic illness. Recent data supports this contention (Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2011; Powers & Oltmanns, 2013). Frankenburg and Zanarini (2011) followed individuals with BPD over 10 years and found that increases in body mass index (BMI) during this time predicted a greater likelihood of having medical problems, being on disability, and utilizing costly health care resources (Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2011). A recent study utilizing a subset of the current sample found that obesity mediated the association between BPD pathology and obesity-related chronic illnesses (i.e., diabetes, osteoarthritis, and asthma) (Powers & Oltmanns, 2013). Further specifying the nature of the association between BPD pathology and obesity has implications for understanding the development of chronic illnesses among individuals displaying BPD features.

BPD is composed of multiple maladaptive personality traits and is associated with a number of normal personality variants (e.g., neuroticism and conscientiousness) (Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2012). Particularly in community samples, BPD pathology may be associated with obesity through normal personality mechanisms, such as affective instability and impulsivity. These traits are independently associated with BPD pathology in both clinical and community samples (Tragesser & Robinson, 2009; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, 2003), may account for differential features of BPD (Tragesser & Robinson, 2009), and are associated with obesogenic behaviors and weight status (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Rieger et al., 2010).

Affective instability in the context of BPD refers to the tendency to experience rapid shifts in negative mood states in response to events or challenges (APA, 2000; Koenigsberg et al., 2002). The affect regulation model of binge eating (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991) posits that eating narrows cognitive focus away from aversive self-awareness to concrete behaviors, momentarily reducing negative affect. This process may promote both binge eating and other obesogenic eating behaviors, such as emotional overeating (Elfhag & Morey, 2008). Thus, affective instability may lead to weight gain as eating is used to cope with intense negative emotions (Rieger et al., 2010). No studies to date have directly examined the relationship between affective instability and obesity. Nonetheless, given the centrality of this construct to BPD and the body of evidence linking BPD pathology to BMI, it is important to clarify the associations among them.

Impulsivity is a multidimensional trait defined as the tendency toward deficient planning and control (Guerrieri, Nederkoorn, & Jansen, 2008). Impulsivity may impact weight by making it diffi-cult for individuals to control habitual responses to food cues, and to plan and follow-through with healthy behaviors. The UPPS (Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation-Seeking) Impulsivity Scale was developed through a factor analysis of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory to encompass the major dimensions of impulsivity (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), and is validated in clinical and community samples (Magid & Colder, 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). The four factors of the UPPS scales correspond to the following NEO facets: Impulsiveness (i.e., Urgency: the ability to control urges and delay gratification); deliberation (i.e., Premeditation: the tendency to think about and plan actions); self-discipline (i.e., Perseverance: the tendency to remain focused on a task); and excitement-seeking (i.e., Sensation-seeking: the tendency to pursue exciting activities).

In one study, the UPPS scales accounted for 64% of variance in BPD (Whiteside et al., 2005). Impulsiveness/urgency and self-discipline/perseverance have shown the strongest and most consistent associations with BPD pathology (Lynam, Miller, Miller, Bornovalova, & Lejuez, 2011; Tragesser & Robinson, 2009; Whiteside et al., 2005). In a large, 10 year longitudinal study of weight change over adult development, overweight and obese participants were found to be more impulsive and excitement-seeking, and less self-disciplined than normal-weight peers, with the impulsiveness facet showing the strongest association with overweight status (Sutin, Ferrucci, Zonderman, & Terracciano, 2011). Other studies have produced similar findings in relation to weight status (Mobbs, Crépin, Thiéry, Golay, & Van der Linden, 2010; Terracciano et al., 2009) and eating behavior (Elfhag & Morey, 2008; Mobbs et al., 2008). Studies have also found that impulsivity is predictor of success in weight loss treatment (Nederkoorn, Jansen, Mulkens, & Jansen, 2007; Sullivan, Cloninger, Przybeck, & Klein, 2007).

This is the first study to examine whether impulsivity and affective instability mediate the association between BPD pathology and BMI. Whereas most studies have relied on self-report questionnaires to measure personality, current analyses include both self and informant report of normal personality variants as informants provide an important and unique perspective on personality (Huprich, Bornstein, & Schmitt, 2011). To date most studies of BPD and obesity have focused on younger and clinical samples; the current study fills a gap in the literature by focusing on a community sample of older adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and informants

Analyses include baseline data from a representative community sample 1630 adults (ages 55 and 64) residing in the St. Louis, Missouri area, who participated in a longitudinal study of personality, aging, and health (St. Louis Personality and Aging Network – SPAN) (Oltmanns & Gleason, 2011). Participants were recruited utilizing listed phone numbers that were crossed with census data in order to identify households with at least one member in the target age range. At baseline, each participant completed an assessment battery including a semi-structured diagnostic interview for personality disorders and self-report questionnaires. The research was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board and was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association.

Analyses included data from 1064 participants (mean age = 59.5 years; 62% female). Individuals were primarily excluded from present analyses because we did not begin collecting height and weight information until January 2009, resulting in missing baseline BMI data for the first 552 participants (34%). Additionally, fourteen individuals declined to provide weight data (<1%). One-third of participants identified as black (N = 351), 63.8% as white (N = 679), and 3.2% as other. Thirty-five percent of participants (n = 373) had a high school education or less, 54% (n = 508) completed a bachelor degree or higher. The majority of the sample was overweight (33.9%) or obese (42.1%).

Eighty-nine percent of all participants provided an informant. Twenty-eight percent of informants were black, 59% were white, and 13% identified as other. Participants reported knowing their informants for an average of 32 years. The majority of informants were significant others (45%), followed by other family members (e.g., sibling, child; 24.1%). The rest of informants were friends, neighbors, and co-workers. Half of informants resided with the participant.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. BPD pathology

BPD pathology was measured using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) (Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997), which is considered the “gold-standard” of personality disorder (PD) assessment. The SIDP-IV is a semi-structured diagnostic interview composed of 101 questions corresponding to DSM-IV criteria for the 10 PDs. Traits are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (“not present or limited to isolated examples”) to 3 (“strongly present”) based on the extent to which they have been present within the past 5 years. All interviews were video recorded and 265 interviews were randomly re-rated by independent observers. The inter-rater reliability of BPD diagnosis was ICC = .77. For analyses, the average of all BPD items was taken to create a mean score.

2.2.2. Mediators

Impulsivity and affective instability were measured with the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The NEO-PI-R is a 240-item questionnaire based on the five-factor model (FFM) of personality, and separates normal-range personality into 5 domains: Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Openness to Experience, and Extraversion. Each of these domains is further represented by 6 facets. Parallel forms of the NEO-PI-R were used for self and informant reports. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Impulsivity scores were calculated by taking the average of NEO impulsiveness, excitement-seeking, deliberation (reverse scored), and self-discipline (reverse scored). Table 1 shows Pearson correlations between impulsivity facets. Significant correlations between facets ranged from .17 to .46 for self-report and .25 to .60 for informant-report (all p's < .001). Excitement-seeking and self-discipline were not significantly correlated. Cronbach's α is .80 for the self-report and .88 for the informant-report full scales. Cronbach's α of the individual facet scores ranged from .60 (excitement-seeking) to .88 (self-discipline).

Table 1.

Correlations between impulsivity facets.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Excitement-seeking (SR) | |||||||

| 2. Impulsiveness (SR) | .17 | ||||||

| 3. Self-discipline (Sr)* | –.05 | .40 | |||||

| 4. Deliberation (SR)* | .17 | .46 | .41 | ||||

| 5. Excitement-seeking (IR) | .46 | .09 | –.02 | .11 | |||

| 6. Impulsiveness (IR) | .14 | .37 | .23 | .23 | .25 | ||

| 7. Self-discipline (Ir)* | .09 | .22 | .42 | .22 | .05 | .53 | |

| 8. Deliberation (IR)* | .17 | .23 | .21 | .29 | .25 | .59 | .60 |

Correlations in bold significant at p < 0.001; SR = self-report; IR = informant-report;

Reverse scored.

Four NEO Neuroticism facets were averaged to create composite affective instability variables: depressiveness, anxiety, angry hostility and vulnerability. These items were chosen based on work examining the assessment of BPD pathology using the FFM. Mullins-Sweat and colleagues (2012) created a reliable and valid measure (the Five Factor Borderline Inventory) composed of items reflecting the FFM traits most theoretically and empirically relevant to BPD (Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2012). The NEO facets of vulnerability and angry hostility were conceptualized as representing emotional dysregulation, and the depressiveness and anxiety facets were conceptualized as representing the tendency to experience negative affect. All 4 facets were included in the current variables because affective instability in BPD is associated with the tendency to experience both frequent shifts in affect and negative emotions in general. Notably, the four-facet measure of affective instability demonstrated slightly better reliability than the two-facet measure (i.e., vulnerability and angry hostility) (α = .91 vs. .83 for self-report; α = .94 vs. .89 for informant-report). Table 2 shows correlations between self- and informant-report affective instability facets. All self-report facets were significantly correlated (r's = .51–.66, all p's < 0.001), as were all informant-report facets (r's = .46–.72, all p's < 0.001). Cronbach's α of the individual facet scores are >.76 for self-report and >.83 for informant-report.

Table 2.

Correlations between affective instability facets.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective instability (SR) | |||||||

| 2. Affective instability (IR) | .66 | ||||||

| 3. Impulsivity (SR) | .51 | .57 | |||||

| 4. Impulsivity (IR) | .61 | .65 | .51 | ||||

| 5. SIDP-IV BPD mean score | .37 | .34 | .28 | .33 | |||

| 6. BMI | .34 | .45 | .32 | .34 | .71 | ||

| 7. Angry Hostility (IR) | .17 | .22 | .37 | .20 | .55 | .52 | |

| 8. Anxiety (IR) | .32 | .35 | .26 | .42 | .65 | .72 | .46 |

Correlations in bold significant at p < 0.001; SR = self-report; IR = informant-report.

2.2.3. Outcome and covariates

BMI, a measure of body mass that accounts for height, is the most widely used measurement of weight status (Flegal et al., 2010). BMI was calculated based on self-reported height and weight by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Although self-reported height tends to be over-estimated and weight under-estimated, both tend to correlate highly with objective measures of height and weight (Stunkard & Albaum, 1981). Race and education were used as covariates in mediation models based on previous evidence of their significance in relation to weight status (Cossrow & Falkner, 2004; House, Kessler, & Herzog, 1990; Ogden et al., 2006).

2.3. Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted with SPSS v. 20. Mediation analysis was used to test our hypotheses. Two mediation models were constructed with BMI as the dependent variable. Self- and informant-report impulsivity and affective instability were included as mediators in the first model, and the individual facets of any significant mediators were included in the second. Pairwise contrasts were calculated to test whether pairs of significant indirect effects were equal in size. Analyses were performed with INDIRECT for SPSS (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), which allows for the examination of the mediating effects of a variable conditional on the effects of the other variables in the model. Bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was utilized to determine significance of mediation effects. Bootstrapping is a preferred method for interpreting mediation analyses because it does not assume that the sampling distributions of the indirect effects are normally distributed, and is preferable to the products-of-coefficients approach in terms of Type I error rate, power, and hypothesis testing (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

3. Results

3.1. Zero-order correlations

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix for BPD pathology, BMI, and NEO measures. The effect size of the association between BPD pathology and BMI was small and significant; this effect size was similar to that between education and BMI (r = –.17), and slightly smaller than that between race and BMI (with black race coded as 1; r = .19). BPD pathology was moderately and significantly associated with all NEO measures. BMI was significantly associated with all NEO measures except informant-report affective instability. Self-report NEO measures were moderately and significantly correlated with their corresponding informant-report measures.

Table 3.

Correlations between impulsivity, affective instability, BPD pathology, and BMI.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective instability (SR) | |||||

| 2. Affective instability (IR) | .46 | ||||

| 3. Impulsivity (SR) | .50 | .24 | |||

| 4. Impulsivity (IR) | .19 | .53 | .45 | ||

| 5. SIDP-IV BPD mean score | .44 | .33 | .34 | .29 | |

| 6. BMI | .11 | .05 | .18 | .21 | .14 |

Correlations in bold significant at p < 0.001. SR = self-report; IR = informant-report; SIDP-IV = Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality; BPD = borderline personality disorder; BMI = body mass index.

3.2. Do impulsivity and affective instability mediate the association between BPD pathology and BMI?

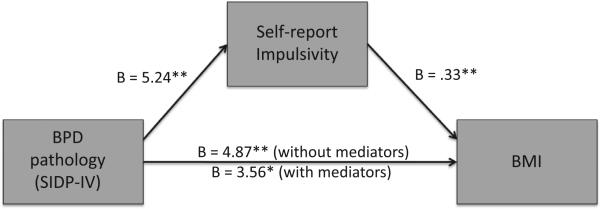

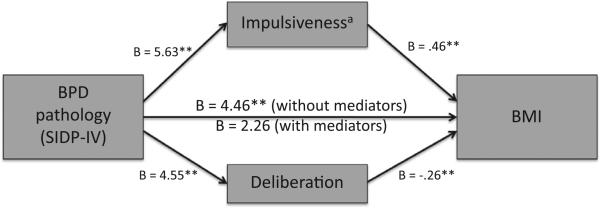

In the first model, only self-report impulsivity was a significant mediator (95% CI [.79–2.93]), such that greater BPD pathology was associated with higher BMI through greater self-reported impulsivity (Fig. 1). This model accounted for a significant amount of variance in BMI (R2 = .08, p < 0.001), and the total indirect effect was significant (95% CI [.05–2.57]). The second model included each facet of self-report impulsivity as potential mediators (Fig. 2). Significant mediators were impulsiveness (95% CI [1.82–3.63]) and (lack of) deliberation (95% CI [–1.92 to –.63]), such that BPD pathology was associated with higher BMI through greater impulsiveness and deliberation. This model accounted for a significant amount of variance in BMI (R2 = .13, p < 0.001), and the total indirect effect was significant (95% CI [1.21–3.34]). Pairwise contrasts revealed that impulsiveness was a stronger mediator than deliberation (contrast 95% CI [2.68–5.17]).

Fig. 1.

Mediating effect of self-report impulsivity on the association between BPD pathology and BMI. *p < .01, **p < .001; covariates: race & education.

Fig. 2.

Mediating effects of self-report impulsiveness and deliberation facets on the association between BPD pathology and BMI. *p < .01, **p < .001, astrongest mediator per pairwise contrasts; covariates: race & education.

The impulsiveness facet of impulsivity includes two items directly related to eating (i.e., “when I am having my favorite foods, I tend to eat too much” and “I sometimes eat myself sick”). To determine specificity of effects, analyses were re-run with these items removed. Results varied slightly. The pattern of results remained the same with two exceptions. In the first model, informant- rather than self-report impulsivity was the only significant mediator (95% CI [.60–2.44]). In model 2, greater BPD pathology was additionally associated with higher BMI through lower self-discipline (95% CI [.74–2.40]). Pairwise contrasts revealed that impulsiveness and self-discipline were stronger mediators than deliberation. Their effects did not significantly differ from each other.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study examined mediators of the association between BPD pathology and BMI in a community sample of older adults. Analyses reveal that problems controlling urges, rather than a tendency to experience rapid mood changes, drive the cross-sectional relationship between BPD pathology and BMI. Specifically, the FFM facet impulsiveness, defined as a diminished ability to control learned, habitual responses to stimuli (e.g., highly palatable foods), was the strongest mediator. Effective weight loss interventions focus on establishing and maintaining a balanced diet and exercise plan (Wing & Hill, 2001), which may be difficult in the face of problems controlling pre-potent responses to obesogenic behaviors. Thus, inhibitory control deficits may serve as a marker for weight status and/or future weight gain among those with BPD pathology.

Higher deliberation and lower self-discipline were also signifi-cant mediators. Studies have tended not to find an association between deliberation and BMI. Current findings may seem counter-intuitive but they may not be surprising. Overweight individuals often attempt to control their weight, and may spend a great deal of time planning to eat healthy and exercise (exhibit high deliberation). However, if an individual has problems following through with these plans (low self-discipline) and controlling urges (high impulsiveness), they may be less likely to lose weight. This finding may differ from previous research due to the age of the current sample, as older adults may have struggled with weight problems for many years. It would be beneficial to determine if such an effect carries over into younger adult samples and whether these features affect treatment success.

We conducted analyses with eating-related items excluded in order to determine whether they were driving effects. Results suggest that eating-related impulsivity was not responsible for our results. The finding that informant- rather than self-report impulsivity was a mediator per this analysis suggests that when eating behavior is not considered, informant-reports are a better marker of weight problems than self-reports in individuals with BPD pathology. These findings are consistent with evidence supporting the benefits of informant-reports, such as research showing that informant-reports are often a better predictor of negative outcomes than self-report alone (Huprich et al., 2011; Oltmanns, Fiedler, & Turkheimer, 2004).

Individual differences in BPD pathology may have implications for the treatment of weight problems. Future weight loss intervention studies would benefit by examining impulsivity as a treatment moderator. Doing so would be a valuable component of developing and implementing a stepped care model for the treatment of obesity, whereby patients are matched to the appropriate level of care based on the severity of their weight problem and the presence of complicating pathology such as BPD. Further, weight change would be an important outcome to include in BPD treatment studies, as many address impulsive behavior. It is important to keep in mind that impulsivity is often seen as a sequela of affective instability in BPD (Sebastian, Jacob, Lieb, & Tuscher, 2013). It is unclear the directional nature of these traits within our sample, but this may not be of specific importance if impulsivity is the critical factor maintaining weight difficulties at this stage of life. Future studies may examine whether targeting emotion dysregulation has an impact on weight in the absence of, or in addition to, targeting impulsivity, and which treatment focus may most benefit long-term weight loss.

A few limitations of the current study should be kept in mind. Findings are cross-sectional, leaving conclusions about the direction of the association between BPD pathology and BMI open to question. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether impulsivity mediates this association over time. In addition, it is possible that our impulsivity measure was more valid than our affective instability measure. The rationale for utilizing the current measure of impulsivity is based on a strong body of evidence for its reliability and validity, whereas the rationale for constructing the current measure of affective instability is primarily conceptual. It will be crucial for future studies to replicate current results with validated normal personality measures of affective instability. Furthermore, self-reported data may be limited by biases (e.g., social desirability) that negatively influence their validity. Informant-reports may also be limited by such biases, especially since participants chose their informants. However, the inclusion of both respondents enhances the robustness and meaningfulness of conclusions (Galione & Oltmanns, 2004; Huprich et al., 2011). Finally, the generalizability of these findings to other age groups and populations should be considered carefully, as this research was conducted with individuals in a relatively narrow age range and geographical area. One major benefit of the current sample is that most BPD research up to this point has focused on younger adults. BPD pathology may have a stronger impact on the health of older adults who are at greater risk for chronic and acute illnesses. Nonetheless, it is essential to evaluate the associations between personality and obesity across the lifespan and in clinical populations.

This is the first study to examine normal personality mechanisms of the association between BPD pathology and BMI. Results of the current study demonstrate that impulsivity, and deficient inhibitory control in particular, mediates this association in later adulthood. Targeting impulsivity may enhance the effectiveness of weight control interventions for a subset of overweight and obese individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH077840) and the Washington University Chancellor's Graduate Fellowship. We thank Merlyn Rodrigues, Tami Curli, Rickey Louis, Christie Spence, Erin Lawton, Krystle Disney, Janine Galione, Hannah King, Amber Bolton, Marci Gleason, Yana Weinstein, and Josh Oltmanns for their assistance with data collection and management.

Ethical Statement

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH077840) and the Washington University Chancellor's Graduate Fellowship. These funding sources did not have any involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication. We complied with APA ethical standards, the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association, and the Uniform Requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals in the treatment of participants. This work is approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board. No financial conflicts of interest influenced the research for, or preparation of, the present manuscript.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text revision American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cossrow N, Falkner B. Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89:2590–2594. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gabalawy R, Katz LY, Sareen J. Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:641–647. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e10c7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K, Morey LC. Personality traits and eating behavior in the obese: Poor self-control in emotional and external eating but personality assets in restrained eating. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini M. Relationship between cumulative BMI and symptomatic, psychosocial, and medical outcomes in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25:421–431. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1660–1665. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Obesity and obesity-related illnesses in borderline patients. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:71–80. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galione J, Oltmanns TF. Personality traits. In: Hopwood CJ, Bornstein RF, editors. Multimethod Clinical Assessment. Guilford; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. The effect of an impulsive personality on overeating and obesity: current state of affairs. Psihologijske teme. 2008;17:265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR. Age, socioeconomic status, and health. The Milbank Quarterly. 1990:383–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huprich SK, Bornstein RF, Schmitt TA. Self-report methodology is insufficient for improving the assessment and classification of Axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25:557–570. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Schmeidler J, New AS, Goodman M, et al. Characterizing affective instability in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:784–788. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller JD, Miller DJ, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW. Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: A test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders. 2011;2:151–160. doi: 10.1037/a0019978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS impulsive behavior scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1927–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs O, Crépin C, Thiéry C, Golay A, Van der Linden M. Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs O, Ghisletta P, Van der Linden M. Clarifying the role of impulsivity in dietary restraint: A structural equation modeling approach. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:602–606. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A., 3rd Personality change influences mortality in older men. Psychological Science. 2007;18:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins-Sweatt SN, Edmundson M, Sauer-Zavala S, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Widiger TA. Five-factor measure of borderline personality traits. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:475–487. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.672504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in obese children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1071–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Fiedler ER, Turkheimer E. Traits associated with personality disorders and adjustment to military life: Predictive validity of self and peer reports. Military Medicine. 2004;169:207–211. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Gleason MEJ. Personality, health, and social adjustment in later life. In: Cottler LB, editor. Mental health in public health: The next 100 years. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. pp. 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Powers AD, Oltmanns TF. Borderline personality pathology and chronic health problems in later adulthood: The mediating role of obesity. Personality Disorders. 2013;4(2):152–159. doi: 10.1037/a0028709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AD, Oltmanns TF. Personality disorders and physical health: A longitudinal examination of physical functioning, healthcare utilization, and health-related behaviors in middle-aged adults. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26:524–538. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher V, Bégin C, Gagnon-Girouard M-P, Tremblay A, Boivin S, Lemieux S. Personality traits in overweight and obese women: Associations with BMI and eating behaviors. Eating behaviors. 2008;9:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): Causal pathways and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Monteith D. Obesity, borderline personality symptomatology, and body image among women in a psychiatric outpatient setting. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:76–79. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<76::aid-eat12>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian A, Jacob G, Lieb K, Tuscher O. Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: A matter of disturbed impulse control or a facet of emotional dysregulation? Current Psychiatry Reports. 2013;15:339. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0339-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Albaum JM. The accuracy of self-reported weights. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1981;34:1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Klein S. Personality characteristics in obesity and relationship with successful weight loss. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:669–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Terracciano A. Personality and obesity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:579–592. doi: 10.1037/a0024286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Sutin AR, McCrae RR, Deiana B, Ferrucci L, Schlessinger D, et al. Facets of personality linked to underweight and overweight. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:682–689. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a2925b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Robinson RJ. The role of affective instability and UPPS impulsivity in borderline personality disorder features. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:370–383. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turiano NA, Pitzer L, Armour C, Karlamangla A, Ryff CD, Mroczek DK. Personality trait level and change as predictors of health outcomes: Findings from a national study of Americans (MIDUS). The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67:4–12. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2001;21:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]