Abstract

The transmembrane protein, linker for activation of T cells (LAT), is essential for T-cell activation and development. Phosphorylation of LAT at multiple tyrosines creates binding sites for the adaptors Gads and Grb2, leading to nucleation of multiprotein signaling complexes. Human LAT contains five potential binding sites for Gads, of which only those at Tyr171 and Tyr191 appear necessary for T-cell function. We asked whether Gads binds preferentially to these sites, as differential recognition could assist in assembling defined LAT-based complexes. Measured calorimetrically, Gads-SH2 binds LAT tyrosine phosphorylation sites 171 and 191 with higher affinities than the other sites, with the differences ranging from only several fold weaker binding to no detectable interaction. Crystal structures of Gads-SH2 complexed with phosphopeptides representing sites 171, 191 and 226 were determined to 1.8−1.9 Å resolutions. The structures reveal the basis for preferential recognition of specific LAT sites by Gads, as well as for the relatively greater promiscuity of the related adaptor Grb2, whose binding also requires asparagine at position +2 C-terminal to the phosphorylated tyrosine.

Keywords: Gads, Grb2, LAT, SH2 domain, tyrosine phosphorylation

Introduction

Engagement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) triggers a cascade of biochemical events culminating in T-cell proliferation and differentiation. Of particular importance to this process is the transmembrane adaptor protein, linker for activation of T cells (LAT), which is believed to coordinate the assembly of a multiprotein signaling complex at the plasma membrane (Zhang et al, 1998; Samelson, 2002; Jordan et al, 2003). Following TCR ligation, LAT becomes rapidly phosphorylated at multiple tyrosine residues by Src or Syk family protein tyrosine kinases. Phosphorylation of LAT creates binding sites for the Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of other signaling molecules, notably the enzyme phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1), and the adaptors Grb2 and Gads (Samelson, 2002; Jordan et al, 2003). The Grb2 protein comprises a central SH2 domain flanked by two Src homology 3 (SH3) domains that mediate the translocation of a variety of signaling proteins to phosphorylated LAT, including Sos and Cbl. In addition to an SH3–SH2–SH3 motif, Gads contains a unique proline-rich region between the SH2 and the C-terminal SH3 domains. Gads interacts through its C-terminal SH3 with the adaptor SLP-76, thereby recruiting this protein and its associated molecules (Vav, Nck, Itk, ADAP) to LAT. Mice with targeted disruptions of LAT or SLP-76 exhibit a complete block in thymic development and lack peripheral T cells (Clements et al, 1998; Pivniouk et al, 1998; Zhang et al, 1999). Gads-deficient mice have a similar, although less severe, phenotype (Yoder et al, 2001).

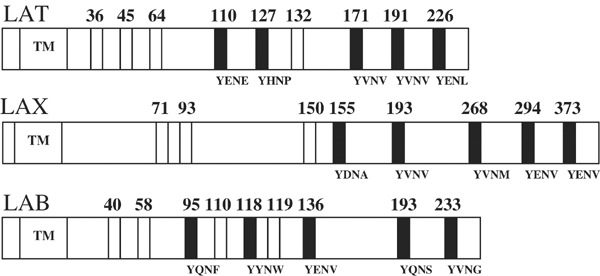

Human LAT contains 10 tyrosines in its cytoplasmic tail, of which nine (36, 45, 64, 110, 127, 132, 171, 191 and 226) are conserved among the mouse, rat and human forms of LAT (Figure 1) (Zhang et al, 1998; Samelson, 2002). Of these, only the five membrane-distal tyrosines (127, 132, 171, 191 and 226) appear to undergo phosphorylation upon TCR engagement (Zhu et al, 2003). Tyr132 is within a PLCγ1-binding motif when phosphorylated, such that mutation of Tyr132 abolishes PLCγ1 binding to LAT in stimulated T cells (Zhang et al, 2000; Lin and Weiss, 2001). Five other tyrosines (110, 127, 171, 191 and 226) constitute potential binding sites for Grb2 and Gads, whose SH2 domains are unusual in requiring asparagine at position +2 C-terminal to the phosphorylated tyrosine for high-affinity binding (pTyr-X-Asn, where X is any amino acid) (Songyang et al, 1993, 1994; Liu and McGlade, 1998; Kessels et al, 2002). To identify the minimal tyrosines required for LAT function, LAT-deficient Jurkat cells have been transfected with various tyrosine mutants of human LAT (Zhang et al, 2000; Lin and Weiss, 2001; Zhu et al, 2003). Surprisingly, only three tyrosines (132, 171 and 191) out of a total of 10 were found to be necessary and sufficient for Ca2+ immobilization following TCR engagement, although full reconstitution of Erk activation also required Tyr226 (Lin and Weiss, 2001; Zhu et al, 2003). Furthermore, these critical tyrosines must be present on the same LAT molecule for recovery of function, strongly suggesting that LAT directs the formation of a discrete signaling complex that is stabilized by interactions among multiple protein domains (Lin and Weiss, 2001). Based on these and other (Samelson, 2002; Jordan et al, 2003) results, this complex is believed to have the following composition: LAT/Gads/SLP-76/PLCγ1, in which Gads binds LAT at Tyr171 and Tyr191, while PLCγ1 binds LAT at Tyr132. In addition, binding of Grb2 to Tyr226 appears to stabilize the interaction between Gads and LAT (Zhu et al, 2003). Recently, an LAT equivalent in B cells, designated LAB (or NTAL), was identified (Brdicka et al, 2002; Janssen et al, 2003), as well as another adaptor, termed LAX, that may negatively regulate TCR-mediated T-cell activation (Zhu et al, 2002) (Figure 1). Like LAT, both LAB and LAX contain multiple tyrosine motifs for binding Grb2 and/or Gads. These studies establish a general role for LAT-like molecules in lymphocyte activation and development.

Figure 1.

Potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites in LAT and LAT-like molecules. LAT (Zhang et al, 1998) and LAB (Brdicka et al, 2002; Janssen et al, 2003) contain nine conserved tyrosines (numbered) in their cytoplasmic domain. LAX (Zhu et al, 2002) contains eight such tyrosines. The transmembrane region (TM) is indicated. Potential binding sites for Gads or Grb2, based on the occurrence of a Tyr-X-Asn motif, are indicated as black bars along with their primary sequence (Songyang et al, 1993, 1994; Liu and McGlade, 1998; Kessels et al, 2002); white bars indicate other sites.

As LAT contains five potential binding sites for Gads, of which only those at positions 171 and 191 are essential for T-cell function (Zhang et al, 2000; Lin and Weiss, 2001; Zhu et al, 2003), we asked whether Gads binds preferentially to these sites, as even small affinity differences could help coordinate the ordered assembly of a defined signaling complex on the LAT molecule. On the other hand, equally tight binding of Gads to all the five tyrosine phosphorylation sites might be expected to reduce the overall efficiency of the assembly process. As measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), we found that the SH2 domain of Gads (Gads-SH2) displays a higher affinity for phosphopeptides representing LAT sites 171 and 191, with differences relative to other sites ranging from only several fold lower to no detectable binding. To understand the basis for preferential recognition of these LAT sites, we determined the crystal structures of Gads-SH2 in complex with selected tyrosyl phosphopeptides. The structures show that specific interactions predominantly at the +1 binding site and less so at +3 site of Gads account for the observed affinity differences towards LAT sites. The structures also reveal significant differences in the binding sites of Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 that can explain differences in the specificity of these closely related domains, both of which require asparagine at the +2 position of the peptide.

Results and discussion

Thermodynamic analysis of LAT phosphopeptide binding to Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2

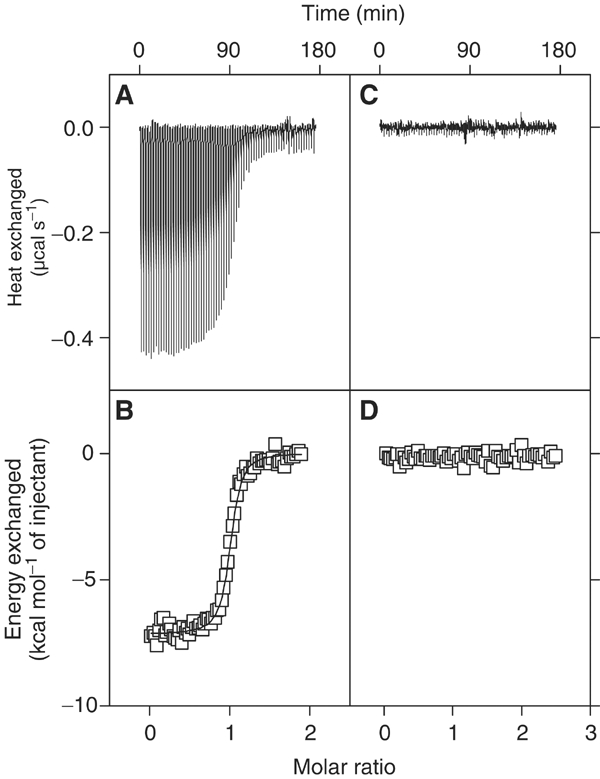

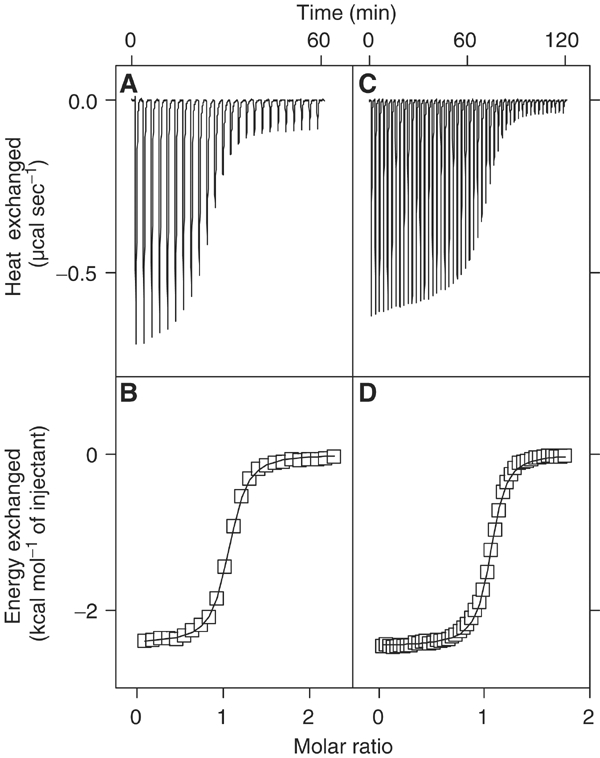

The binding of Gads-SH2 (Figure 2) and Grb2-SH2 or GST-Grb2-SH2 (Figure 3) to six-residue phosphopeptides representing LAT tyrosine phosphorylation sites 110 (ASpYENE), 127 (DDpYHNP), 132 (PGpYLVV), 171 (DDpYVNV), 191 (REpYVNV) and 226 (PDpYENL) was measured by ITC (Table I). As expected, neither Gads-SH2 nor Grb2-SH2 bound to pLAT132, which is a binding site for PLCγ1. This apart, and except for pLAT127, which does not bind Gads-SH2 (see below), and binds Grb2-SH2 weakly with unfavorable enthalpy (endothermic), the reactions are enthalpically driven, with a favorable entropic component, a thermodynamic profile characteristic of other SH2/phosphopeptide interactions (Ladbury et al, 1996; McNemar et al, 1997; Bradshaw and Waksman, 1998). Gads-SH2 binds pLAT171 and pLAT191 equally well (Kb=4.92 × 106 and 5.34 × 106 M−1, respectively, at 11°C) (Figure 2A and B; Table I), implying the absence of significant specificity determinants N-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, as reported for other SH2 domains (Bradshaw and Waksman, 2002). The affinity for pLAT226 (Kb=0.87 × 106 M−1) is ∼6-fold lower, while that for pLAT110 is only ∼2-fold less (2.32 × 106 M−1). However, as LAT Tyr110 is not detectably phosphorylated in vivo (Zhu et al, 2003), and therefore cannot serve as a physiological binding site for Gads, we exclude this site from further consideration. In contrast to Gads-SH2, Grb2-SH2 binds pLAT171, pLAT191 and pLAT226 with similar affinities (Table I). Binding results from ITC were independently confirmed for Gads-SH2 by surface plasmon resonance using directionally immobilized pLAT peptides (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Calorimetric titration of Gads-SH2 with LAT tyrosyl phosphopeptides. (A) Raw data obtained from 70 automatic injections of 4 μl aliquots of 0.37 mM pLAT 171 solution into 0.043 mM Gads-SH2 solution in PBS (pH 7.2±0.1) at 284 K. (B) Nonlinear least-squares fit (solid line) of the incremental heat per mole of added ligand (open squares) for the titration in (A). The c value for this ITC experiment was 211. (C) Raw data obtained from 70 automatic injections of 4 μl aliquots of 0.49 mM pLAT 127 into 0.043 mM Gads-SH2 in PBS (pH 7.2±0.1) at 284 K. (D) Incremental heat per mole of added ligand (open squares) for the titration in (C). The plots were generated using Origin.

Figure 3.

Calorimetric titration of Grb2-SH2 and GST-Grb2-SH2 with pLAT191. (A) Raw data obtained from 24 automatic injections of 6 μl aliquots of 1.15 mM pLAT191 solution into 0.054 mM Grb2-SH2 solution in PBS (pH 7.2±0.1) at 284 K. (B) Nonlinear least-squares fit (solid line) of the incremental heat per mole of added ligand (open squares) for the titration in (A). The c value for this ITC experiment was 87. The thermodynamic parameters obtained for this titration were n=1.03±0.003, Kb=1.61±0.07 × 106 M−1 and −ΔHob=2.43±0.01 kcal mol−1. (C) Raw data obtained from 48 automatic injections of 6 μl aliquots of 0.98 mM pLAT191 into 0.125 mM GST-Grb2-SH2 in PBS (pH 7.2±0.1) at 284 K. (D) Nonlinear least-squares fit (solid line) of the incremental heat per mole of added ligand (open squares) for the titration in (C). The c value for this ITC experiment was 188. The thermodynamic parameters obtained for this titration were n=1.05±0.002, Kb=1.50±0.06 × 106 M−1 and −ΔHob=2.46±0.01 kcal mol−1. These values are indistinguishable from those obtained using the isolated Grb2-SH2 domain. The plots were generated using Origin.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic quantities for the recognition of LAT-derived tyrosyl phosphopeptides by SH2 domains of Gads and Grb2 at 284K

| Protein | Peptide | Kb (× 106 M−1) | − ΔGbo (kcal mol−1) | − Δ Hbo (kcal mol−1) | TΔSbo (kcal mol−1) | ΔSbo (cal mol−1 K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gads | ASpY110ENE | 2.32 (±0.14) | 8.27 | 6.08 (±0.03) | 2.19 | 7.7 |

| DDpY127HNP | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | |

| PGpY132LVV | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | |

| DDpY171VNV | 4.92 (±0.49) | 8.70 | 7.17 (±0.04) | 1.53 | 5.4 | |

| REpY191VNV | 5.34 (±0.45) | 8.74 | 5.39 (±0.02) | 3.35 | 11.8 | |

| PDpY226ENL | 0.87 (±0.13) | 7.72 | 3.60 (±0.06) | 4.12 | 14.5 | |

| DDpY*HNV | 0.13 (±0.01) | 6.65 | 1.25 (±0.02) | 5.40 | 19.0 | |

| DDpY*VNP | 0.24 (±0.01) | 7.00 | 5.60 (±0.04) | 1.40 | 4.9 | |

| DDpY*VNL | 2.51 (±0.20) | 8.32 | 4.60 (±0.02) | 3.72 | 13.1 | |

| Grb2 | ASpY110ENE | 0.59 (±0.05) | 7.49 | 7.38 (±0.07) | 0.11 | 0.4 |

| DDpY127HNP | Weak | ∼4 | ∼−3 | — | — | |

| PGpY132LVV | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | |

| DDpY171VNV | 0.43 (±0.02) | 7.31 | 3.56 (±0.02) | 3.75 | 13.2 | |

| REpY191VNV | 1.50 (±0.06) | 8.03 | 2.46 (±0.01) | 5.57 | 19.6 | |

| PDpY226ENL | 0.69 (±0.02) | 7.59 | 4.58 (±0.01) | 3.01 | 10.6 | |

| DDpY*HNV | 0.07 (±0.01) | 6.26 | 1.12 (±0.02) | 5.14 | 18.1 | |

| |

DDpY*VNP |

0.004 (±0.0002) |

4.74 |

3.30 (±0.08) |

1.44 |

5.1 |

| Asterisk (*) indicates artificial sequence. The stoichiometry (n) values ranged from 0.98 to 1.21, with uncertainties from 0.2 to 0.8%. The values in parentheses represent uncertainties of fit. NB is no binding. Weak refers to a detectable binding, albeit with equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd, in the millimolar range, wherein −ΔGbo and −ΔHbo were estimated by nonlinear least-squares analysis only with fixed stoichiometry (n=1). | ||||||

No binding of pLAT127 to Gads-SH2 could be detected by ITC, even by injecting large volumes of peptide solution at concentrations greater than 100-fold molar excess over 0.043 mM Gads-SH2 (Figure 2C and D). As even miniscule heats of binding should be detectable under these conditions, it remained to be seen as to how Gads-SH2 helps restrict the specificity of this domain to exclude binding to LAT at Tyr127, which is known to undergo phosphorylation following T-cell activation (Lin and Weiss, 2001). However, it was possible to detect the weak binding of pLAT127 by Grb2-SH2. As reported previously, Pro at the +3 position of target peptides reduces their binding by Grb2 (Muller et al, 1996). In order to test whether the differential reduction in affinity of Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 towards LAT site 127 (DDpYHNP) is due to +1 His or +3 Pro, or a combination of both, we measured the binding of the artificial sequences DDpYHNV and DDpYVNP to Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2. For reference, we compared the results obtained against the ability of Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 to bind to LAT site 171 (DDpYVNV). This analysis revealed that Grb2-SH2 is less tolerant than Gads-SH2 to Pro at the +3 position. Conversely, His at the +1 position reduces the binding of Gads 38-fold, but only seven-fold for Grb2, conferring a penalty to favorable free energy change by 2.05 and 1.05 kcal mol−1, respectively (Table I). Grb2 being less selective at the +1 site ends up being more promiscuous than Gads towards LAT (Table I), insofar as Grb2 does not clearly discriminate among pLAT171, pLAT191 and pLAT226.

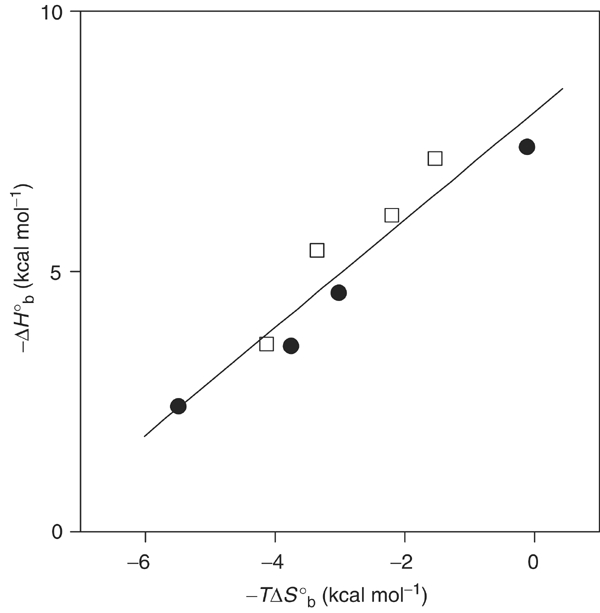

The recognition of pLAT peptides by Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 exhibits entropy–enthalpy compensation (Figure 4), whereby losses in enthalpic contributions such as hydrogen-bonding interactions are compensated by entropic gains such as release of motional restrictions. This isoequilibrium phenomenon is believed to arise from solvent reorganization associated with binding (Grunwald and Steel, 1995; Swaminathan et al, 1998; Rekharsky and Inoue, 2002). In the Gads-SH2/pLAT and Grb2-SH2/pLAT interactions, displacement of solvent molecules from hydrophobic surfaces of the binding partners could provide a favorable entropic contribution to complex formation.

Figure 4.

Enthalpy–entropy compensation plot of −ΔHob as a function of −TΔSob for the binding of LAT tyrosyl phosphopeptides (pLAT110, pLAT171, pLAT191 and pLAT226) to Gads-SH2 (open squares) and Grb2-SH2 (solid circles). The straight line obtained by linear regression analysis using Origin has a slope of 1.03±0.13 (r=0.95).

Overview of the Gads-SH2/pLAT complexes

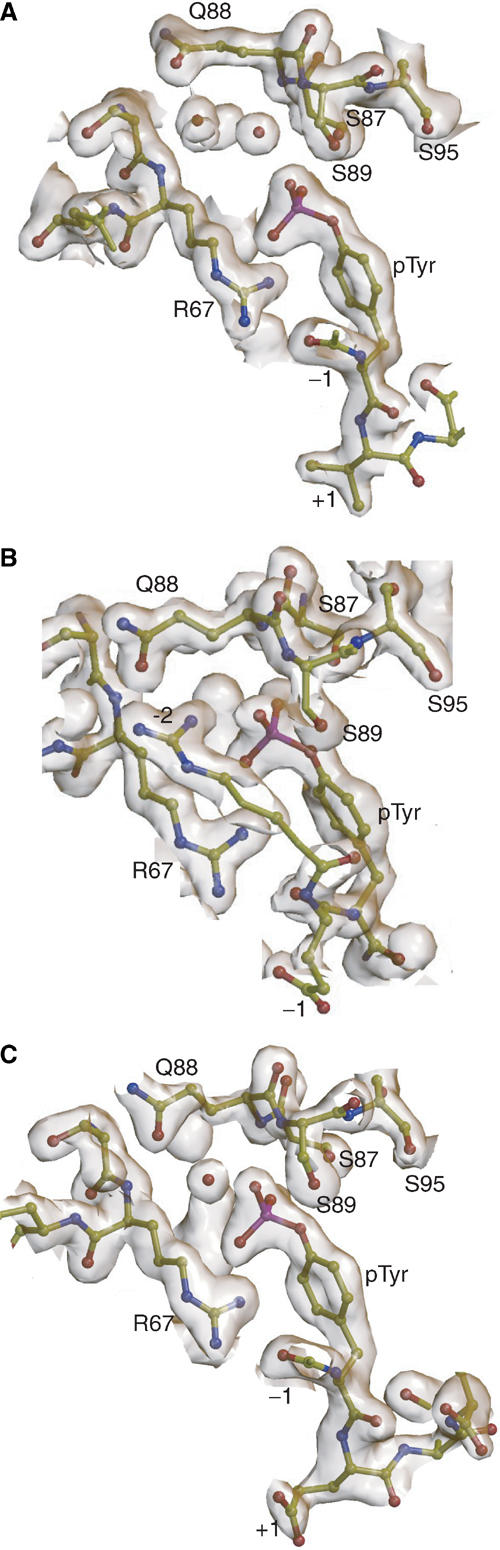

To understand the basis for preferential recognition of LAT tyrosine phosphorylation sites 171 and 191 by Gads, we determined the crystal structures of Gads-SH2 in complex with three LAT phosphopeptides to high resolution: (1) Gads-SH2/pLAT171 (1.8 Å), (2) Gads-SH2/pLAT191 (1.8 Å) and (3) Gads-SH2/pLAT226 (1.9 Å). We failed to crystallize a Gads-SH2/pLAT127 complex, consistent with the lack of binding by ITC. The final σA-weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density maps in the region of the phosphotyrosyl residues are shown in Figure 5; data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table II. There are four molecules in the asymmetric unit of the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 crystal, two in the Gads-SH2/pLAT191 crystal and four in the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 crystal. The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) deviation in α-carbon positions for these molecules, excluding the bound peptides and nine flexible N-terminal residues, ranges between 0.3 and 0.6 Å.

Figure 5.

σA-weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density isosurfaces around phosphotyrosyl residues in Gads-SH2/pLAT complexes. (A) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT171 (1.8 Å resolution, 1.5σ contour level). (B) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT191 (1.8 Å resolution, 1.5σ contour level). (C) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT226 (1.9 Å resolution, 1.5σ contour level). Selected residues are labeled and water molecules are shown as red balls. Isosurfaces were generated using CONSCRIPT (Lawrence and Bourke, 2000).

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for Gads-SH2/pLAT complexes

| Gads-SH2/pLAT171 | Gads-SH2/pLAT191 | Gads-SH2/pLAT226 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Crystal | |||

| Space group | P41212 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | a=b=90.31, c=145.96 | a=42.71, b=52.81, c=43.97, β=101.38° | A=50.64, b=117.94, c=50.59, β=108.92° |

| No. of molecules per asymmetric unit | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| (B) Data collection | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 63.86–1.79 | 43.10–1.62 | 52.30–1.84 |

| No. of observations | 128176 | 117803 | 133713 |

| No. of unique reflections | 57265 | 26632 | 41324 |

| Completeness (%)a | 97.8 (75.5) | 96.6 (95.5) | 92.72 (68.4) |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 4.9 (37.2) | 4.3 (32.0) | 6.5 (35.6) |

| (C) Refinement | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.00–1.80 | 40.00–1.80 | 30.00–1.90 |

| Reflections in working setc | 50339 (2553) | 15639 (1216) | 38882 (1937) |

| Reflections in test set | 2679 (5.1%) | 858 (5.2%) | 2073 (5.1%) |

| Rcryst (%)c,d | 19.8 (31.4) | 16.7(29.2) | 21.7 (33.2) |

| Rfree (%)c,e | 24.1 (33.6) | 21.8(34.1) | 25.8 (35.6) |

| (D) Final model | |||

| No. of non-hydrogen atoms | 3909 | 1953 | 4009 |

| No. of water molecules | 312 | 142 | 353 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Main chain | 35.3 | 19.5 | 27.8 |

| Side chains | 40.0 | 22.7 | 32.3 |

| Root-mean-square deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.024 | 0.023 | 0.037 |

| Bond angles (°) |

2.0 |

1.9 |

2.9 |

| a Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell (1.89–1.79 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT171, 1.71–1.62 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT191 and 1.95–1.84 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT226). | |||

| b Rmerge(I)=(∑∣I(i)−〈I(h)〉∣/∑I(i)), where I(i) is the ith observation of the intensity of the hkl reflection and 〈I〉 is the mean intensity from multiple measurements of the hkl reflection. | |||

| c Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell (1.85–1.80 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT171, 1.85–1.80 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT191 and 1.95–1.90 Å for Gads-SH2/pLAT226). | |||

| d Rcryst (F)=∑∣∣Fobs(h)∣−∣Fcalc(h)∣∣/∑∣Fobs(h)∣; ∣Fobs(h)∣ and ∣Fcalc(h)∣ are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes for the hkl reflection. | |||

| e Rfree is calculated over reflections in a test set not included in atomic refinement. | |||

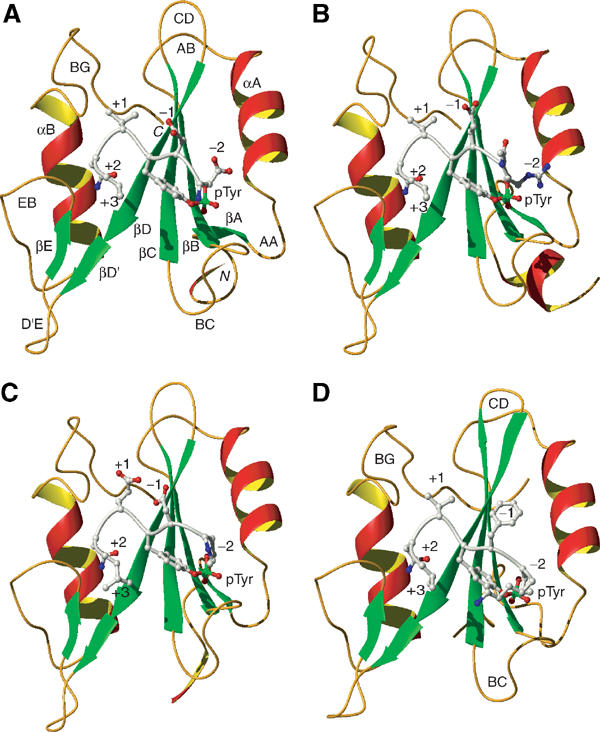

As expected, the overall fold of the Gads-SH2 domain is similar to that of other SH2 domains, with a central anti-parallel β-sheet composed of three strands, βB, βC and βD, that are flanked on either side by two α-helices, αA and αB (Figure 6; Bradshaw and Waksman, 2002). The phosphate group of the LAT peptides is situated in a deep hydrophilic cavity, where it is stabilized by an intricate network of hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions. In particular, Arg85 (ArgβB5), which is strictly conserved in SH2 domains, makes a bidentate ionic interaction with two oxygens of the phosphate moiety, while Arg67 (ArgαA2) forms a bidentate hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of the −1 peptide residue and a phosphate oxygen in all the three complexes. Arg67 also participates in an unusual amino–aromatic interaction with the phenol ring of the phosphotyrosine (Figure 5), a type of cation–π interaction (Zacharias and Dougherty, 2002) found in some SH2 domain structures, such as the SH2 of Lck tyrosine kinase (Eck et al, 1993). A second positively charged residue, Lys108 (LysβD6), which is located on the opposite face of phosphotyrosine phenol ring from Arg67, flanks one side of the binding cavity and is involved in hydrophobic interactions with the phenol ring and +3 residue of the bound peptides. Three serines, at positions 87, 89 and 95, form additional hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety.

Figure 6.

Ribbon diagrams of Gads-SH2 and Grb2 structures. (A) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT171. (B) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT191. (C) Gads-SH2 in complex with pLAT226. (D) Grb2-SH2 in complex with KPFpYVNV (PDB entry code 1tze) (Rahuel et al, 1996). Secondary structure elements are labeled following the nomenclature for Lck-SH2 (Eck et al, 1993), and are colored as follows: α-helices, red and yellow; β-strands, green; and loop regions, gold. The N- and C-termini are labeled. The bound peptides are silver, with side chain oxygen and nitrogen atoms colored red and blue, respectively, and phosphorus atoms green.

As in the known Grb2-SH2/phosphopeptide structures (Rahuel et al, 1996; Ettmayer et al, 1999), the bound LAT peptides adopt a type I β-turn conformation at the +2 position, because the bulky side chain of Trp120 (Trp121 in Grb2) in the EB loop of Gads-SH2 occludes the +3 binding pocket (Figure 7). In other SH2 structures, for example that of Src-SH2 (Waksman et al, 1992), the peptide binds in an extended conformation, such that the +3 peptide residue occupies a hydrophobic pocket in the protein, conferring a modest degree of selectivity (Bradshaw and Waksman, 1999, 2002; Bradshaw et al, 1999, 2000). To achieve specificity despite the loss of interactions at the +3 binding site, the Gads SH2 domain forms several hydrogen bonds, via main chain atoms, with the side chain of +2 Asn, as observed in Grb2-SH2/phosphopeptide complexes (Rahuel et al, 1996; Ettmayer et al, 1999): +2 Asn Oδ1−O Lys108, +2 Asn Oδ1−O Lys119 and +2 Asn Nδ2−N Lys108.

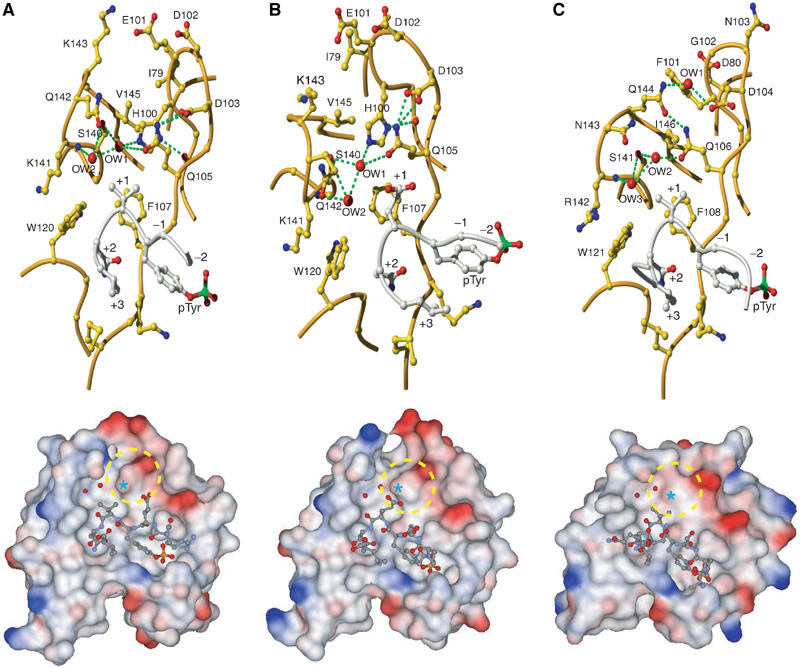

Figure 7.

Comparison of the +1 binding site in Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 structures. (A) Upper panel: View of the specificity-determining region of the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 complex showing details of the +1 binding site. Waters (OW) in the vicinity of +1 Val are represented as red balls. Lower panel: Molecular surface of Gads-SH2, with the bound pLAT171 peptide drawn in ball-and-stick representation. Solvent-accessible surfaces are colored according to electrostatic potential, with positively charged regions in blue and negatively charged regions in red. Surface potentials were calculated using GRASP (Nicholls et al, 1991). The +1 binding pocket is circled. The position of Gln105 is marked by an asterisk. (B) Upper panel: Specificity-determining region of the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex showing the +1 binding site, including waters in the vicinity of +1 Glu. Lower panel: Molecular surface of Gads-SH2 with bound pLAT226 peptide. (C) Upper panel: Specificity-determining region of the Grb2-SH2/KPFpYVNV complex (PDB entry code 1tze) (Rahuel et al, 1996) showing the +1 binding site, including waters in the vicinity of +1 Val. Lower panel: Molecular surface of Grb2-SH2 with bound KPFpYVNV peptide. The +1 binding pocket is circled; the asterisk marks the position of Gln106.

Basis for preferential binding to LAT tyrosine phosphorylated sites 171 and 191

As measured by ITC (Table I), Gads-SH2 binds pLAT171 and pLAT191 with six-fold higher affinity than pLAT226; there is no detectable interaction with pLAT127. Examination of the crystal structures of Gads-SH2 bound to pLAT171, pLAT191 and pLAT226, and of a modeled Gads-SH2/pLAT127 complex, provides insights into the source of these specificity differences.

Both pLAT171 and pLAT191 have Val at the +1 position, whereas pLAT226 has Glu. In the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex (Figure 7B), the +1 Glu side chain makes four van der Waals contacts with Phe107: +1 Glu Cβ−Cδ1 Phe107, +1 Glu Cβ−Cɛ2 Phe107, +1 Glu Cγ1−Cɛ2 Phe107 and +1 Glu Cγ1−Cζ Phe107. In the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 and Gads-SH2/pLAT191 complexes (Figure 7A), the +1 Val side chain interacts with Trp120 and Gln105, as well as Phe107, resulting in nine total contacts: +1 Val Cγ1−Cζ2 Trp120, +1 Val Cγ1−Cη2 Trp120, +1 Val Cγ1−Cɛ2 Phe107, +1 Val Cγ1−Cζ Phe107, +1 Val Cγ2−Cζ Phe107, +1 Val Cγ2−Cβ Gln105, +1 Val Cβ−Cγ1 Phe107, +1 Val Cβ−Cɛ2 Phe107 and +1 Val Cβ−Cζ Phe107. Concomitant with these additional interactions, the predominantly apolar surface area buried by +1 Val in the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 and Gads-SH2/pLAT191 interfaces (98 Å2) is ∼50% greater than that buried by +1 Glu in the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex (67 Å2). These structural differences should favor Val over Glu at the +1 peptide position, in agreement with Kb measurements (Table I); however, their full effect on affinity may be partially offset by differences at the +3 binding site. Although +3 Val of pLAT171 (or pLAT191) and +3 Leu of pLAT226 interact only weakly with Gads-SH2 (one and three van der Waals contacts, respectively), +3 Leu contributes 47 Å2 of buried surface to the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 interface, compared to 32 Å2 by +3 Val in the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 and Gads-SH2/pLAT191 complexes. On this basis alone, one might expect peptides containing a pTyr-Val-Asn-Leu motif to bind somewhat tighter to Gads-SH2 than the pLAT peptides containing the pTyr-Val-Asn-Val motif tested here. Contrary to this expectation, we found that the artificial peptide DDpYVNL binds to Gads-SH2 with nearly two-fold lower affinity than pLAT171 or pLAT191 (Table I). The results point to the nontrivial nature of structure-based affinity prediction in this system, as in many others, and suggest that biophysical factors in addition to buried surface areas, such as shape complementarity, conformational flexibility and solvent effects, must be considered. Thus, the slightly reduced affinity of DDpYVNL could arise from steric hindrance between +3 Leu and Gads-SH2 due to the larger size of Leu than Val, offsetting the small favorable free energy gain expected from burying ∼15 Å2 of additional surface. However, Gads discriminates among LAT sites more effectively than Grb2, despite its lower stringency at the +3 position. Consequently, it is the ability of Gads-SH2 to discriminate better at +1 vis-à-vis Grb2-SH2 that confers the observed specificity differences towards the respective sites on LAT.

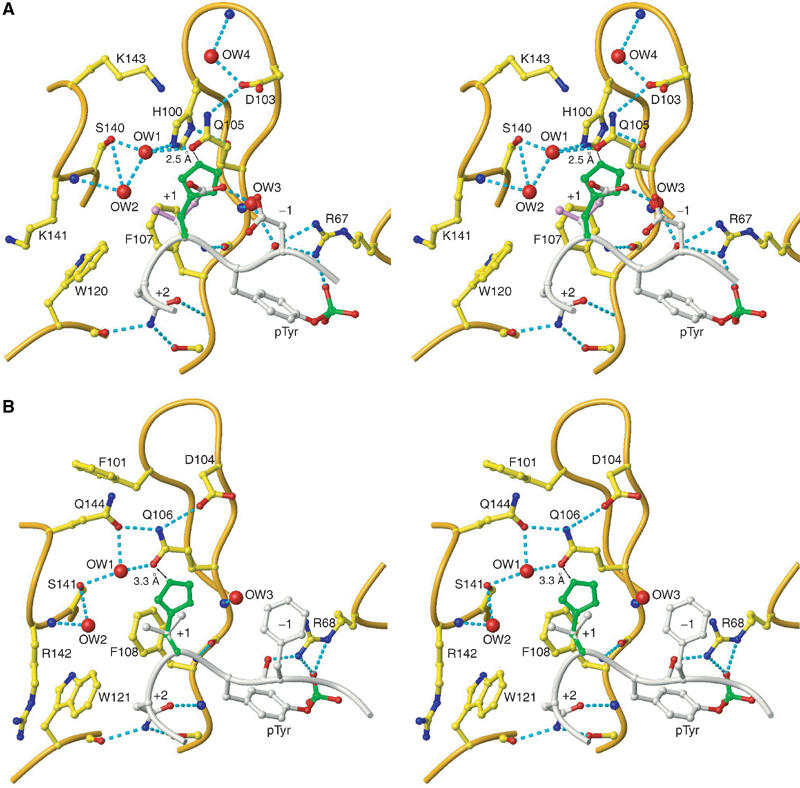

To understand why pLAT127, which has His at the +1 position, has reduced affinity for the Gads-SH2 domain, we modeled this residue in place of +1 Glu in the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 crystal structure and of +1 Val in the complex between Grb2-SH2 and KPFpYVNV (Materials and methods). In the modeled Gads-SH2/PDpYHNL structure (Figure 8A), the close approach of the +1 His and Gln105 side chains (2.5 Å between +1 His Cɛ1 and Gln105 Oɛ1; 2.8 Å between +1 His Nɛ2 and Gln105 Oɛ1) implies that His cannot be easily accommodated in the Gads +1 binding site without incurring considerable energetic penalties. This is consistent with the ITC results on the artificial sequence DDpYHNV binding to Gads-SH2, which is recognized to be 38 times weaker than DDpYVNV (Table I), thus accounting for a loss in favorable free energy change by 2.05 kcal mol−1 for accommodating His at the +1 position. By contrast, in the modeled Grb2-SH2/KPFpYHNV structure (Figure 8B), the Gln106 side chain lies beneath that of +1 His, where it is held fixed by a hydrogen-bonding network involving several SH2 residues (see below). As the closest distance between the +1 His and Gln106 side chains is 3.3 Å (between +1 His Cɛ1 and Gln106 Oɛ1), His is expected to fit in the +1 binding pocket without significant steric hindrance. Indeed, our ITC results show that Grb2-SH2 readily accommodates His at the +1 position, with only a seven-fold loss in equilibrium association constant as compared to Val at +1 (Table I). The results are corroborated by the recent demonstration that Grb2 binds with high affinity to phosphopeptides having His at the +1 position (Suenaga et al, 2003).

Figure 8.

Stereo images of Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 structures. (A) View of the +1 binding site in the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex. Relevant stretches of the Gads-SH2 polypeptide backbone are cream; labels identify side chains and bound waters (red balls) in the vicinity of +1 Glu of pLAT226 (silver). The side chain of the modeled +1 His residue is green. (B) The +1 binding site in the Grb2-SH2/KPFpYVNV complex (PDB entry code 1tze) (Rahuel et al, 1996). The Grb2-SH2 polypeptide backbone is cream. Side chains and waters (red balls) in the vicinity of +1 Glu of the bound peptide (silver) are labeled; the modeled +1 His is green.

Comparison of Gads and Grb2 SH2 domains

Superposition of the SH2 domains of Gads and Grb2 (53% sequence identity) results in an r.m.s. difference of 0.98 Å for 95 α-carbon atoms, indicating close overall similarity. With respect to LAT recognition, the SH2 domains differ primarily at the +1 binding site, located between the BG loop and βD strand (Figure 6). In the Grb2-SH2/phosphopeptide structures (Rahuel et al, 1996; Ettmayer et al, 1999), the side chain of Phe101 (which corresponds to His100 in Gads) is directed towards the solvent, while the Gln106 side chain forms direct and solvent-mediated hydrogen bonds with Gln144 and Ser141, respectively (Figure 7C). As a consequence, the side chains of Gln106 and Gln144 are interlocked at a position below that of +1 Val of the phosphopeptide, creating a relatively open +1 binding pocket that should be able to accommodate larger side chains. Indeed, phosphotyrosine library selection experiments have demonstrated that the Grb2-SH2 domain retains high affinity for peptides with Lys, Arg and Met at the +1 position, as well as Ile, Glu and Gln (Songyang et al, 1993, 1994; Kessels et al, 2002).

Although the phosphopeptide binding specificity of the Gads SH2 domain has not been characterized in detail, the crystal structures reported here suggest that Gads-SH2 should be less promiscuous towards LAT than Grb-SH2, due to greater selectivity at the +1 site. In the Gads-SH2/pLAT complexes (Figure 7A and B), the side chain of His100, unlike that of Grb2 Phe101 (Figure 7C), is sandwiched between the BG loop and βD strand, where it points towards the interior of the protein. The difference is presumably attributable to the smaller size of Gads His100 and Val145, compared to Grb2 Phe101 and Ile146, which avoids steric clashes between their side chains, and permits the imidazole nitrogen of Gads His100 to hydrogen bond with the main chain oxygen of Val98. The position of His100 is further stabilized by buttressing residues Ile79, Glu101, Lys143 and Val145. As a result, His100 displaces the Gln105 side chain up from the surface of the SH2 domain, where the side chain forms a hydrogen bond with Asp103. In contrast to Gln106 of Grb2, the corresponding Gln105 of Gads is unable to interact with Gln142 (Gln144 in Grb2) and is, therefore, located above the level of the +1 peptide residue on the SH2 surface (Figure 7A and B). This protrusion partially occludes the +1 binding site of Gads, relative to that of Grb2 (Figure 7C), and interferes with the accommodation of bulky side chains at this site. In addition, two bound water molecules, captured within a hydrogen-bonding network involving His100, Gln105, Ser140 and Lys141, further constrict the Gads +1 binding site (Figure 7A and B). Notably, both waters are conserved in all 10 copies of the Gads-SH2 molecule in the three complex crystals. Although ordered waters are found at equivalent positions in some Grb2-SH2 structures (Rahuel et al, 1996) (Figure 7C), they would not interfere with the placement of large side chains over Grb2 Gln106, which does not protrude into the +1 binding site. In agreement with this analysis, Gads-SH2 prefers Val over Glu (reduced binding) or His (highly compromised binding) at the +1 phosphopeptide position, whereas Grb2-SH2 is very tolerant of substitutions at this position (Songyang et al, 1993, 1994; Kessels et al, 2002; Suenaga et al, 2003). Moreover, Grb2-SH2 binds LAT sites without much selectivity (Table I), insofar as it recognizes pLAT171, pLAT191 and pLAT226 with similar affinities.

Conclusions

Although we have demonstrated preferential binding of the Gads SH2 domain to the tyrosine-phosphorylated sites of LAT known to be essential for T-cell activation (Zhang et al, 2000; Lin and Weiss, 2001; Zhu et al, 2003), it is unlikely that the observed affinity differences are sufficient to permit Gads to diffuse freely through the cytosol and interact only with these target sites, a problem that also confronts other SH2 domain-containing proteins (Bradshaw and Waksman, 2002). Indeed, the narrowness of the free energy window between specific and nonspecific interactions suggests that, in general, SH2 domains alone do not contain all the necessary components for selective recognition of protein targets (Bradshaw and Waksman, 1999, 2002; Bradshaw et al, 1999, 2000). Similar considerations apply to other signaling modules that bind peptide ligands, including SH3, WW, PTB and PDZ domains (Ladbury and Arold, 2000).

How, then, is an efficient signal transduction system that maintains fidelity and minimizes noise, while amplifying a specific signal, designed? Nature appears to have evolved a three-tiered strategy to address this challenge, each of whose key elements probably operates in the assembly of LAT-based signaling complexes. At the most basic level, not all potential binding sites for SH2 domains necessarily undergo tyrosine phosphorylation in vivo. Thus, while Gads-SH2 binds the synthetic peptide pLAT110 nearly as well as pLAT171 or pLAT191 (Table I), LAT is not phosphorylated at Tyr110 following TCR ligation (Zhu et al, 2003). Potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Figure 1) on the LAT-like adaptors LAB (Brdicka et al, 2002; Janssen et al, 2003) and LAX (Zhu et al, 2002) probably also display selective phosphorylation. Indeed, recent results from Zhang and co-workers have shown that, of the five Tyr-X-Asn motifs present in LAB (Figure 1), only the distal three tyrosines pLAB136 (pYENV), pLAB193 (pYQNS) and pLAB233 (pYVNG) of LAB are phosphorylated and bind to Grb2 (Koonpaew et al, 2004). However, LAB does not encounter Gads in vivo as Gads is not expressed in B cells. Acting in concert with selective phosphorylation is the intrinsic binding specificity, albeit limited, of the SH2 domains themselves, as manifested by the somewhat higher affinities of Gads-SH2 for pLAT171 and pLAT191 compared to pLAT226, and by the lack of binding to pLAT127. In LAX, there may be preferential binding of Gads to sites pLAX193 (pYVNV) and pLAX268 (pYVNM), both of which, akin to LAT, have Val at the +1 position. Site pLAX193 (pYVNV), being identical to the core pLAT171 and pLAT191 sequences, may be expected to bind tightly to Gads.

Ultimately, however, it appears that nature employs multiprotein complexes to achieve efficient signal transduction. If individual binary interactions are relatively weak (i.e., micromolar), as for Gads alone binding to phosphorylated LAT, then chance collisions between signaling proteins would not generate noise. On the other hand, multicomponent complexes can, in principle, take advantage of cooperativity, such that the weak interactions in binary complexes are replaced by much stronger and more specific interactions in higher-order complexes. Accordingly, in the putative LAT/Gads/SLP-76/PLCγ1 complex (Lin and Weiss, 2001), the intermediate-to-low affinity of SH2, SH3 and other signaling domains for their cognate peptides may be compensated either by additional contacts outside the linear peptide sequences, or by the concerted binding of two or more domains in one protein to multiple interaction sites in another, to ensure ordered assembly of a defined complex. Moreover, the highly conserved spacing between phosphorylation sites in human and rodent forms of LAT (Zhang et al, 1998; Samelson, 2002) suggests that this process requires precise positioning of SH2-containing adaptors along the LAT molecule. Future efforts will be aimed at quantitating possible cooperative binding interactions in the LAT/Gads/SLP-76/PLCγ1 complex by ITC and other biophysical techniques, and at visualizing specific protein–protein interfaces by X-ray crystallography.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

A DNA fragment encoding the SH2 domain of mouse Gads (residues 50–147) was amplified by PCR using a forward primer containing a BamHI cleavage site at the start codon (5′-TTTTTTTTGGATCCTTTATAGATATCGAGTTTCCTGAGTGGT TCCATGA-3′) and a reverse primer containing a SalI site (5′-TTTTTTTTGTCGACTTAATCCCGAAGGAAGACCTGCTTCT GTTTGGAGAT-3′). A DNA fragment encoding the SH2 domain of mouse Grb-2 (residues 60–153) was amplified by PCR using a forward primer (5′-TTTTTTTTGGATCCTGGTTTTTTGGCAAAATCCCC-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-TTTTTTTTGTCGACTTACTGTTCTATGTCCCGCAGG-3′). The amplified DNAs were cloned into the BamHI/SalI site of the bacterial expression vector pGEX-4T-1(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) and transformed in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The GST-SH2 fusion proteins were expressed by induction with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside at 30°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS and disrupted by sonication using a Branson Sonifier. The supernatant was applied to a GSTrap FF column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and the fusion proteins were purified according to standard protocols. The eluted proteins were digested with thrombin protease (Amersham Biosciences) overnight at room temperature. Gads-SH2 and Grb2-SH2 were further purified by gel filtration chromatography in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) with a Superdex 75 HR column (Amersham Biosciences). Fractions containing the SH2 domain were loaded onto a Mono Q anion exchange column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated in the same buffer, and bound protein was eluted using a linear NaCl gradient. Protein concentrations were measured by absorbance at 280 nm using calculated extinction coefficients of 15220, 13940 and 54620 M−1 cm−1 for Gads-SH2, Grb2-SH2 and GST-Grb2-SH2, respectively (Pace et al, 1995).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC was carried out on a MicroCal VP-ITC titration microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northhampton, MA, USA). Tyrosyl-phosphorylated peptides were synthesized and purified by Biosource (Hopkinton, MA, USA). Purified Gads-SH2, Grb2-SH2 or GST-Grb2-SH2 were exhaustively dialyzed against PBS (5 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 136 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl); the final dialysate was used to prepare tyrosyl phosphopeptide solutions. In a typical experiment, 1–10 μl aliquots of 0.3–9.0 mM phosphopeptide solution were injected from a 250 μl rotating syringe at 310 rpm into the sample cell containing 1.37 ml of 0.012–0.125 mM protein solution. The duration of each injection varied from 2 to 20 s, while the delay between injections was 150 s. For each titration experiment, an identical buffer dilution correction was conducted; these heats of dilution were subtracted from the corresponding binding experiment.

A computerized nonlinear least-squares fitting method was used to determine the thermodynamic parameters of LAT phosphopeptide binding by SH2 domains of Gads and Grb2 (Table I). Measurements of the change in enthalpy ΔHob, the equilibrium association constant Kb and the molar stoichiometry n of the recognition reaction were made from single titration experiments. Reversible equilibrium thermodynamics was assumed in calculating values of the change in free energy, ΔGbo, from the relationship, ΔGbo = −RTln Kb. The change in entropy, ΔSbo, was calculated from ΔGbo = ΔHbo − TΔSbo. The c value, a product of binding affinity and initial macromolecule concentration in the ITC cell, was 37<c<435, well within the ideal range of 10–500 for measurement of Kb and ΔHbo from a single ITC experiment. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using the software package Origin provided by the manufacturer.

Crystallization and data collection

Purified Gads-SH2 was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 0.25 mM EDTA, 60 mM NaCl and concentrated to 12 mg ml−1. Co-crystallization with LAT phosphopeptides was carried at room temperature in hanging drops from mixtures containing a five-fold molar excess of peptide over protein. For pLAT171 (DDpYVNV), tetragonal bipyramidal crystals grew to a size of 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.5 mm3 under conditions of 0.1 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) and 2.5 M ammonium sulfate. For pLAT191 (REpYVNV), plate-like crystals of dimensions 0.05 × 0.4 × 0.5 mm3 were obtained in 0.1 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.7) and 2.5 M ammonium sulfate. For pLAT226 (PDpYENL), prismatic crystals as large as 0.3 × 0.5 × 0.6 mm grew from 0.1 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) and 2.5 M ammonium sulfate.

Diffraction data were collected at 100 K using an R-axis IV++ image plate detector equipped with Osmic mirrors and mounted on a Rigaku rotating anode Cu-Kα X-ray generator. Saturated LiSO4 was used as a cryoprotectant for the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 and Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex crystals. Crystals were soaked in an 8:2 (v/v) mixture of cryoprotectant to reservoir solution and flash-cooled in a liquid nitrogen stream. For the Gads-SH2/pLAT191 complex, the cryoprotectant was prepared by inclusion of 25% (v/v) glycerol in the mother liquor. Data collection statistics are summarized in Table II.

Structure determination and refinement

The structure of the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 complex was solved by the molecular replacement method using the program Molrep in CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project No. 4, 1994). A homology-modeled Gads-SH2 domain (Peitsch, 1996), based on a known Grb2-SH2 structure (PDB entry code 1bmb) (Ettmayer et al, 1999), was used as a search model. When all the four monomers in the asymmetric unit had been located, the correlation coefficient was 0.394 and the R value was 54.8% for the data between 20 and 4.0 Å. Rigid body refinement, using 20.0–4.0 Å data, resulted in R and Rfree values of 48.7 and 51.3%, respectively. Refinement was initially performed with CNS (Brünger et al, 1998), with positional refinement followed by simulated annealing to 3000 K, and finally individual B-factor refinement. Manual model rebuilding was carried out between each run with the σA-weighted 2Fo–Fc maps, using the program Xfit in the XtalView package (McRee, 1999). After CNS refinement converged at R and Rfree values of 25.2 and 27.9%, respectively, further refinement was carried out with the program Refmac5 in CCP4. Rcryst at the end of the refinement was 19.8% for 50339 reflections (F>2σ) to 1.80 Å and Rfree was 24.1% for 2679 reflections. All main chains and side chains, except those of four N-terminal residues, were clearly visible in 2Fo–Fc electron density maps. Refinement statistics are summarized in Table II.

The structure of the Gads-SH2/pLAT191 complex was solved with Molrep (Collaborative Computational Project No. 4, 1994) using the Gads-SH2 structure from the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 complex as a search model. When both monomers in the asymmetric unit had been located, the correlation coefficient was 0.446 and the R value was 44.7% for data between 40.0 and 3.0 Å. Rigid body refinement, using 40.0–3.0 Å data, gave R and Rfree values of 45.7 and 49.3%, respectively. Further refinement was performed using the same protocol as for the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 complex. N-terminal residues 1–4 of both SH2 molecules in the asymmetric unit were not seen in the electron density and were omitted from the model. The final Rcryst was 17.9% for 15639 reflections (F>2σ) at 1.80 Å resolution and Rfree was 22.5% for 2679 reflections (Table II).

The Gads-SH2/pLAT226 structure was solved similarly. When all the four monomers in the asymmetric unit had been located, the correlation coefficient was 0.518 and the R value was 45.4% for data between 40.0 and 3.0 Å. Rigid body refinement, using 20.0–3.0 Å data, resulted in R and Rfree values of 42.7 and 44.8%, respectively. Further refinement was performed as for the Gads-SH2/pLAT171 structure. Residues 1–4 of two of the four SH2 molecules in the asymmetric unit were not visible in the electron density and were omitted from the model. The final Rcryst was 20.3% for 15 533 reflections (F>2σ) at 1.80 Å resolution and Rfree was 25.5% for 2539 reflections (Table II). Changes in solvent-accessible surface areas were calculated using NACCESS (Hubbard and Thornton, 1996).

Atomic coordinates for the Gads-SH2/pLAT171, Gads-SH2/pLAT191 and Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complexes have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession codes 1R1P, 1R1Q and 1R1S, respectively.

Modeling of histidine at the +1 binding site

Residues +1 Glu of the Gads-SH2/pLAT226 complex and +1 Val of the Grb2-SH2/KPFpYVNV complex (PDB entry code 1tze) (Rahuel et al, 1996) were replaced by histidine with XtalView (McRee, 1999), and the resulting structures were subjected to energy minimization using AMBER 6.0 (Case et al, 1999). Only the side chain atoms of the residues immediately surrounding the +1 site (+1 Glu or +1 Val, Gln105, Phe107 and Trp120) were allowed to move. Energy minimizations were carried out using 200 cycles of steepest descent minimization, followed by 300 cycles of conjugate gradient algorithm, until the r.m.s. value of the potential energy gradient was less than 0.1 kcal mol−1 Å−1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nazzareno Dimasi for advice on protein expression and to Eric Sundberg for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI36900) and the Sandler Program for Asthma Research to RAM.

References

- Bradshaw JM, Mitaxov V, Waksman G (1999) Investigation of phosphotyrosine recognition by the SH2 domain of the Src kinase. J Mol Biol 293: 971–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JM, Mitaxov V, Waksman G (2000) Mutational investigation of the specificity determining region of the Src SH2 domain. J Mol Biol 299: 521–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JM, Waksman G (1998) Calorimetric investigation of proton linkage by monitoring both the enthalpy and association constant of binding: application to the interaction of the Src SH2 domain with a high-affinity tyrosyl phosphopeptide. Biochemistry 37: 15400–15407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JM, Waksman G (1999) Calorimetric examination of high-affinity Src SH2 domain-tyrosyl phosphopeptide binding: dissection of the phosphopeptide sequence specificity and coupling energetics. Biochemistry 38: 5147–5154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JM, Waksman G (2002) Molecular recognition by SH2 domains. Adv Protein Chem 61: 161–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brdicka T, Imrich M, Angelisova P, Brdickova N, Horvath O, Spicka J, Hilgert I, Luskova P, Draber P, Novak P, Engels N, Wienands J, Simeoni L, Osterreicher J, Aguado E, Malissen M, Schraven B, Horejsi V (2002) Non-T cell activation linker (NTAL): a transmembrane adaptor protein involved in immunoreceptor signaling. J Exp Med 196: 1617–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges N, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D 54: 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Pearlman DA, Caldwell JW, Cheatham TE, III Ross WS, Simmerling CL, Darden TA, Merz KM, Stanton RV, Cheng AL, Vincent JJ, Crowley MF, Ferguson DM, Radmer RJ, Singh UC, Weiner PK, Kolman PA (1999) AMBER Version 6.0. San Francisco, CA: University of California

- Clements JL, Yang B, Ross-Barta SE, Eliason SL, Hrstka RF, Williamson RA, Koretzky GA (1998) Requirement for the leukocyte-specific adapter protein SLP-76 for normal T cell development. Science 281: 416–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D 50: 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck MJ, Shoelson SE, Harrison SC (1993) Recognition of a high-affinity phosphotyrosyl peptide by the Src homology-2 domain of p56lck. Nature 362: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettmayer P, France D, Gounarides J, Jarosinski M, Martin MS, Rondeau JM, Sabio M, Topiol S, Weidmann B, Zurini M, Bair KW (1999) Structural and conformational requirements for high-affinity binding to the SH2 domain of Grb2. J Med Chem 42: 971–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald E, Steel C (1995) Solvent reorganization and thermodynamic enthalpy–entropy compensation. J Am Chem Soc 117: 5687–5692 [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SJ, Thornton JM (1996) NACCESS Version 2.1.1. London: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College

- Janssen E, Zhu M, Zhang W, Koonpaew S, Zhang W (2003) LAB: a new membrane-associated adaptor molecule in B cell activation. Nat Immunol 4: 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MS, Singer AL, Koretzky GA (2003) Adaptors as central mediators of signal transduction in immune cells. Nat Immunol 4: 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HWG, Ward AC, Schumacher TNM (2002) Specificity and affinity motifs for Grb2 SH2–ligand interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 8524–8529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonpaew S, Janssen E, Zhu M, Zhang W (2004) The importance of three membrane-distal tyrosines in the adaptor protein NTAL/LAB. J Biol Chem 279, 10.1074/jbc.M311394200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladbury JE, Arold S (2000) Searching for specificity in SH domains. Chem Biol 7: R3–R8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladbury JE, Hensmann M, Panayotou G, Campbell ID (1996) Alternative modes of tyrosyl phosphopeptide binding to a Src family SH2 domain: implications for regulation of tyrosine kinase activity. Biochemistry 35: 11062–11069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MC, Bourke P (2000) CONSCRIPT: a program for generating electron density isosurfaces for presentation in protein crystallography. J Appl Crystallogr 33: 990–991 [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Weiss A (2001) Identification of the minimal tyrosine residues required for linker for activation of T cell function. J Biol Chem 276: 29588–29595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SK, McGlade CJ (1998) Gads is a novel SH2 and SH3 domain-containing adaptor protein that binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated Shc. Oncogene 17: 3073–3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar C, Snow ME, Windsor WT, Prongay A, Mui P, Zhang R, Durkin J, Le HV, Weber PC (1997) Thermodynamic and structural analysis of phosphotyrosine polypeptide binding to Grb2-SH2. Biochemistry 36: 10006–10014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee DE (1999) XtalView/Xfit. A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol 125: 156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K, Gombert FO, Manning U, Grossmuller F, Graff P, Zaegel H, Zuber JF, Freuler F, Tschopp C, Baumann G (1996) Rapid identification of phosphopeptide ligands for SH2 domains. Screening of peptide libraries by fluorescence-activated bead sorting. J Biol Chem 271: 16500–16505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B (1991) Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11: 281–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T (1995) How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci 4: 2411–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch MC (1996) ProMod and Swiss-Model: Internet-based tools for automated comparative protein modelling. Biochem Soc Trans 24: 274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivniouk V, Tsitsikov E, Swinton P, Rathbun G, Alt FW, Geha RS (1998) Impaired viability and profound block in thymocyte development in mice lacking the adaptor protein SLP-76. Cell 94: 229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahuel J, Gay B, Erdmann D, Strauss A, Garcia-Echeverria C, Furet P, Caravatti G, Fretz H, Schoepfer J, Grütter MG (1996) Structural basis for specificity of GRB2-SH2 revealed by a novel ligand binding mode. Nat Struct Biol 3: 586–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekharsky MV, Inoue Y (2002) Solvent and guest isotope effects on complexation thermodynamics of α-, β-, and 6-amino-6-deoxy-β-cyclodextrins. J Am Chem Soc 124: 12361–12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samelson LE (2002) Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: the role of adapter proteins. Annu Rev Immunol 20: 371–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofski S, Lechleider RJ, Neel BG, Birge RB, Fajardo JE, Chou MM, Hanafusa H, Schaffhausen B, Cantley LC (1993) SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell 72: 767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, McGlade J, Olivier P, Pawson T, Bustelo XR, Barbacid M, Sabe H, Hanafusa H, Yi T, Ren R, Baltimore D, Ratnofski S, Feldman RA, Cantley LC (1994) Specific motifs recognized by the SH2 domains of Csk, 3BP2, fps/fes, GRB-2, HCP, SHC, Syk, and Vav. Mol Cell Biol 14: 2777–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga A, Hatakeyama M, Ichikawa M, Yu X, Futatsugi N, Narumi T, Fukui K, Terara T, Taiji M, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S, Konagaya A (2003) Molecular dynamics, free energy, and SPR analyses of the interactions between the SH2 domain of Grb2 and ErbB phosphotyrosyl peptides. Biochemistry 42: 5195–5200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan CP, Surolia N, Surolia A (1998) Role of water in the specific binding of mannose and mannooligosaccharides to concanavalin A. J Am Chem Soc 120: 5152–5159 [Google Scholar]

- Waksman G, Kominos D, Robertson SR, Pant N, Baltimore D, Birge RB, Cowburn D, Hanafusa H, Mayer BJ, Overduin M, Resch MD, Rios CB, Silverman L, Kuriyan J (1992) Crystal structure of the phosphotyrosine recognition domain SH2 of v-src complexed with tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides. Nature 358: 646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder J, Pham C, Iizuka YM, Kanagawa O, Liu SK, McGlade J, Cheng AM (2001) Requirement for the SLP-76 adaptor GADS in T cell development. Science 291: 1987–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias N, Dougherty DA (2002) Cation–π interactions in ligand recognition and catalysis. Trends Pharmacol Sci 23: 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP, Samelson LE (1998) LAT: the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell 92: 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Sommers CL, Burshtyn DN, Stebbins CC, DeJarnette JB, Trible RP, Grinberg A, Tsay HC, Jacobs HM, Kessler CM, Long EO, Samelson LE (1999) Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity 10: 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Trible RP, Zhu M, Liu SK, McGlade J, Samelson LE (2000) Association of Grb2, Gads, and phospholipase C-γ1 with phosphorylated LAT tyrosine residues. J Biol Chem 275: 23355–23361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Janssen E, Leung K, Zhang W (2002) Molecular cloning of a novel gene encoding a membrane-associated adaptor protein (LAX) in lymphocyte signaling. J Biol Chem 277: 46151–46158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Janssen E, Zhang W (2003) Minimal requirement of tyrosine residues of linker for activation of T cells in TCR signaling and thymocyte development. J Immunol 170: 325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]