Abstract

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne zoonotic infection affecting people in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Current treatments for cutaneous leishmaniasis are difficult to administer, toxic, expensive, and limited in effectiveness and availability. Here we describe the development and application of a medium-throughput screening approach to identify new drug candidates for cutaneous leishmaniasis using an ex vivo lymph node explant culture (ELEC) derived from the draining lymph nodes of Leishmania major-infected mice. The ELEC supported intracellular amastigote proliferation and contained lymph node cell populations (and their secreted products) that enabled the testing of compounds within a system that mimicked the immunopathological environment of the infected host, which is known to profoundly influence parasite replication, killing, and drug efficacy. The activity of known antileishmanial drugs in the ELEC system was similar to the activity measured in peritoneal macrophages infected in vitro with L. major. Using the ELEC system, we screened a collection of 334 compounds, some of which we had demonstrated previously to be active against L. donovani, and identified 119 hits, 85% of which were confirmed to be active by determination of the 50% effective concentration (EC50). We found 24 compounds (7%) that had an in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI; 50% cytotoxic/effective concentration [CC50]/EC50) > 100; 19 of the compounds had an EC50 below 1 μM. According to PubChem searchs, 17 of those compounds had not previously been reported to be active against Leishmania. We expect that this novel method will help to accelerate discovery of new drug candidates for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniases are the predominant pathologies produced by Leishmania infection, reaching an estimated 1 to 1.5 million annual cases in 88 countries worldwide (1). Among the disease burdens caused by tropical infections, leishmaniasis ranks second in mortality and fourth in morbidity (2). Leishmaniasis is a disease of the poorest populations—people who live under poor housing conditions without adequate sanitation and who are poorly nourished are at increased risk of acquiring infection and developing more-severe disease (3, 4). The World Health Organization includes leishmaniasis among the most neglected diseases and has highlighted the lack of industry interest in the generation of new antileishmanial drugs (because they are a “marketing failure”), with the industry not being able to offset the costs of research and development or to generate an economic profit in the medium to long term (5).

Several drugs are currently available to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis, but each has limitations. The pentavalent antimony compounds (sodium stibogluconate [Pentostam; GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, United Kingdom] and meglumine antimoniate [Glucantime; Aventis, Strasbourg, France]) have been the mainstay of chemotherapy for cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis for more than 50 years. The recommended regimen involves intravenous or intramuscular administration of the drug for 20 days (for localized cutaneous leishmaniasis [LCL]) or 28 days (for mucosal leishmaniasis [ML]). Repeated courses of therapy may be necessary in patients with severe cutaneous lesions or ML. Cure rates with this regimen of 90% to 100% (LCL) and 50% to 70% (ML) were common decades ago, but lower initial cure rates have been noted recently. Mild to moderate adverse effects of antimony therapy are common. Several other therapies have been used increasingly in the treatment of the leishmaniases. Amphotericin B desoxycholate and the amphotericin lipid formulations are very useful in the treatment of ML and in some regions have replaced antimony as the first-line therapy. The use of these drugs, however, is limited by their difficulty of administration, well-known toxicity, and high cost. Oral therapy with miltefosine, a membrane-activating alkylphospholipid, has shown inconsistent efficacy, and after only a few years of use, drug resistance has emerged. Treatment of LCL with oral antifungal drugs such as ketoconazole or fluconazole has had only modest success. Topical treatment of CL with paromomycin plus methylbenzethonium chloride ointment, or with application of heat, has been effective in selected areas in both the Old World and the New World. Parasite resistance has been responsible for some failures of treatment of different Leishmania species infections (6–8). Experimental studies have shown specific and multidrug resistance after incremental exposure of Leishmania to these drugs (9). Although clinical and epidemiological data have shown heterogeneous efficacies of the same drug when used against different Leishmania species/subspecies (10–13), it is presumed that molecules active against one species will have a good chance of being active against other Leishmania species.

Although multiple approaches to the identification of new antileishmanial compounds have been described, there is no clear consensus on which approach is optimal in terms of labor intensity, reproducibility, and biological relevance. In general, high-throughput assays are based on molecular targets, while low- to medium-throughput systems tend to utilize whole organisms in cell-based assays (14). The parasite's enzymatic repertoire and structure (e.g., membrane) have been used as drug targets, but questions have been raised as to the efficacy of these approaches compared with screenings that utilize whole parasites. Most screening methods have used promastigotes (the insect stage of Leishmania) to identify hits; however, these required subsequent validation assays using amastigote-infected macrophages (15–17).

Because immune mechanisms play an important role in the pathogenesis of leishmaniasis, and because successful antileishmanial therapy is greatly influenced by the host immune response (18–20), we sought to screen compounds for antileishmanial activity within the immunopathologic environment of the infected host tissue. To this end, we developed an ex vivo lymph node (LN) cell explant culture system using the skin-draining lymph nodes from BALB/c mice infected in the skin with luciferase (LUC)-transfected Leishmania major. The ex vivo system supported ongoing replication of the parasite (21), which could easily be quantified in a medium-throughput assay by measurement of luciferase activity. Pilot studies demonstrated excellent discrimination between active and inactive compounds, establishing the capability to screen new compounds for antileishmanial activity at a single concentration (for hit identification) or to determine activity by dose-response evaluation (for determination of the 50% effective concentration [EC50]). We demonstrated that this novel approach can be used to efficiently identify new lead compounds that have the potential to enter the pipeline for further testing to identify effective, easier, and cheaper antileishmanial drug candidates. The identification of compounds that had activity against L. major in this model system, from among the members of a set of lead compounds that had been identified previously to be active against L. donovani (21), suggests the potential for these compounds to have broad antileishmanial activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and parasites.

All the procedures involving animals were approved by the IACUC of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, where the studies were initiated, and the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), where the studies were completed. Male BALB/c mice of 6 to 8 weeks of age (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were used in all the experiments. Leishmania major (MHOM/IL/81/Friedlin) promastigotes were transfected with an episomal vector containing the luciferase (luc) reporter gene (22) and subsequently cultured in complete M199 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) (0.12 mM adenine, 0.0005% hemin, 20% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) with the addition of the selective antibiotic Geneticin (G418; Gibco) (10 μg/ml). Parasite virulence was maintained by passing parasites through mice every 2 to 3 months.

Mouse infection and stability of parasite transfection.

Mice were inoculated intradermally at the base of the tail at approximately 3 mm lateral of each side of the spine, with the objective that the infection should involve both subiliac lymph nodes that drain this dermal site. Each inoculum consisted of 107 highly virulent metacyclic promastigotes of L. major (23). We determined the expression level and stability of the luciferase gene transfected in L. major by quantifying the luminometric signal of both subiliac lymph node cells harvested from infected animals at 14, 21, 28, and 35 days postinfection (p.i.). The amastigotes were purified from lymph node tissues at each time point, and a standard curve was developed using microscopic quantification of amastigotes and the corresponding luminometry signal at 2-fold serial dilutions. For this purpose, the amastigotes were harvested from lymph node homogenates and passed through 27.5-gauge and 30.5-gauge needles and then through polycarbonate membrane filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) (pore sizes of 8, 5, and 3 μm). The released amastigotes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and counted by microscopy. The luminescent signal from the parasites was assessed by adding 20 μl of 1× cell culture lysis reagent (Promega), followed by the addition of 100 μl of luciferin substrate at room temperature according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The luciferase activity was then determined in a plate luminometer (FLUOstar Omega; BMG Labtech).

Ex vivo lymph node explant culture (ELEC).

The subiliac lymph nodes of infected animals were aseptically removed and placed in a petri dish containing 2 ml of collagenase D (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) (2 mg/ml)–150 mM NaCl–5 mM KCl–1 mM MgCl2–1.8 mM CaCl2–10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The lymph nodes were infiltrated with collagenase solution and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The cell suspension and remaining tissue fragments were gently passed through a 100-μm-pore size cell strainer (BD, Bedford, MA) to obtain a single-cell suspension, which was washed in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), centrifuged at 500 × g for 7 min at 4°C, and resuspended in 2× supplemented culture medium composed of DMEM (Cellgro), 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 2 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 2× minimum essential medium (MEM) amino acid solution (Sigma), and 20 mM HEPES buffer (Cellgro); the 2× supplemented culture medium becomes 1× when it is added at an equal volume to the plate with the compounds. The proportion of infected macrophages and the number of intracellular amastigotes were determined by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained preparations after 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of ex vivo culture at 34°C and 5% CO2. To determine the parasite burden by luminometry, the 96-well microplates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 7 min and the supernatant was discarded using a multichannel vacuum aspirator (Costar). Then, 20 μl of 1× cell culture lysis reagent (Promega) was added to the wells, followed by the addition of 100 μl of luciferin substrate (Promega) and subsequent reading of the luciferase signal using a plate luminometer (FLUOstar Omega; BMG Labtech). The percentage of parasite inhibition with regard to controls was calculated as 100 − [(parasite counts in treated cells/parasite counts in untreated cells) × 100].

Cell viability of ELEC.

In order to rule out the possibility that the decrease in parasite signal could have been due to host cell death upon exposure to antileishmanial compounds, we used several concentrations of miltefosine, pentamidine, and amphotericin B (Sigma) encompassing the corresponding EC50s of these drugs. We compared the percentages of parasite inhibition by luminometry and cell viability by microscopy using the trypan blue exclusion test (Sigma) (0.4% trypan blue), which is read within 3 to 5 min of dye exposure (24). The percentage of viable cells was calculated as (total number of viable cells per ml of aliquot/total number of cells per ml of aliquot) × 100.

Flow cytometry analysis of the lymph node cell populations.

The cell composition of the lymph node explant was determined in groups of uninfected or infected animals (21 to 28 days after infection) by means of flow cytometry following a method described elsewhere (21). In brief, lymph node cells were adjusted to 106 cells/100 μl in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.025% sodium azide. Then, the cells were blocked for 20 min with PBS containing 2% BSA and 5% normal inactivated serum of the species in which the secondary antibodies were raised and 0.5 μg of mouse BD Fc block. Lymph node T cell subsets were characterized using T Lymphocyte Subset Antibody Cocktail (CD3-phycoerythrin Cy7 [PECy7]/CD4-PE/CD8alpha-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]) (BD), B cells were identified with the Pan B cell marker CD45R/B220-PE, and macrophages and granulocytes were identified with GR1PE/Ly6G-FITC (BD). The percentage of positive cells was determined according to the threshold of the corresponding isotype controls using a FacsAria instrument (BD).

Compound collections.

A total of 334 compounds encompassing collections of indoles, thiuram disulfides, quinolines, fluorenones, benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3-diones, indene-diones and acetophenones, phenothiazines (and related compounds), and 9-aminoacridines, some of which had been identified previously to be effective against visceral leishmaniasis (21), were obtained from commercial and nonprofit sources as follows: Asinex (Moscow, Russia), Chembridge (San Diego, CA), Chemdiv (San Diego, CA), Enamine (Kiev, Ukraine), IBScreen (Moscow, Russia), Maybridge (Trevillett, United Kingdom), Microsource (Gaylordsville, CT), NCI (Developmental Therapeutic Program, Bethesda, MD), Pharmeks (Moscow, Russia), and Specs (Delft, Netherlands). Detailed information is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The compounds from NCI and Microsource libraries were provided in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a 10 mM concentration, while the rest of the compounds were received dry and were subsequently dissolved in DMSO (Sigma; cell culture tested) at the same concentration. All the molecules were stored at −20°C and thawed shortly before each experiment. We used miltefosine, pentamidine, and amphotericin B (Sigma) dissolved in DMSO (Sigma) as positive controls for antileishmanial activity.

Drug screening and EC50 determinations using ELEC.

The antileishmanial efficacy of the compounds was determined using the lymph node explant model in a 96-well plate format. The subiliac lymph node cells were processed using the protocol described above, and a 100,000-cell suspension in 100 μl of a 2× supplemented DMEM culture (described above) was added to clear-bottomed luminescent 96-well plates. ELEC was utilized as a medium-throughput screening system to evaluate 344 compounds in triplicate at a final concentration of 2.5 μM. We used amphotericin B as a positive control in order to calculate the signal/background ratio. After 48 h of incubation at 34°C and 5% CO2, the surviving parasites were quantified by luminometry. The RLUs of the signals were transformed to percentages of parasite inhibition (described previously). Hits were defined as compounds displaying >50% inhibition of light emission (15, 17, 25). The percentage of parasite inhibition with regard to controls was calculated as 100 − [(parasite counts in treated cells/parasite counts in untreated cells) × 100]. The range of the assay window was calculated as mean values of the no-drug control wells/mean values of the drug (amphotericin B)-treated wells (25). The quality of each plate was determined by calculating the Z prime (Z′) factor (26) using the positive and negative controls on each plate. The Z′ factor was calculated as 1 − [(3SD positive controls + 3SD negative controls)/absolute value of (mean of the positive controls − mean of the negative controls)].

To calculate the concentration of the hit compound that killed 50% of the parasites (the EC50), we used 2-fold serial dilutions of test compounds (0.03 to 20 μM) in triplicate and 105 cells per well in 96-well plates. After 48 h of incubation at 34°C and 5% CO2, the leishmanicidal effect was expressed as the percentage of parasite inhibition with respect to controls, assessed by luminometry as previously described. The EC50 was determined by regression analysis using GraphPad (Prism 5.0). The mean of the EC50 from 2 to 3 different experiments was utilized to estimate the final EC50 and rank the compounds based on the in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI).

Determination of EC50 in peritoneal macrophages.

Uninfected mice were sacrificed to obtain resident macrophages by peritoneal lavage with DMEM (Gibco) and heparin (Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NJ) (2 units/ml). The cells were washed twice by centrifugation and resuspended in culture medium composed of 2× supplemented DMEM culture (described above). The peritoneal macrophages were adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2 in flat-bottomed 96-well plates for subsequent infection with L. major. Adherent macrophages were infected at a 1:5 (cell/parasite) ratio with stationary-phase LUC-transfected L. major promastigotes and incubated at 34°C and 5% CO2 for 2 h. The extracellular parasites were then removed by washing with prewarmed Dulbecco's PBS (Gibco). Infected macrophages were exposed to 2-fold serial dilutions of test compounds as described above for the lymph node explant culture. The infected macrophages were incubated for 48 h at 34°C in 5% CO2. The percentage of parasite reduction was determined by luminometry, and the mean EC50 based on the results of 2 to 3 different experiments was calculated as described above. The test compounds with known antileishmanial activity, antimycin A, miltefosine, pentamidine, securinine, amphotericin B, disulfiram, nortriptyline, tetrandrine, monensin A, and quinacrine, were purchased from Sigma; tilorone was purchased from Hangzhou Trylead Chemical Technology Co. (China). All compounds were dissolved in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) (analytical grade, cell culture tested) and stored at −20°C until used.

Assessment of cell toxicity (50% cytotoxicity concentration [CC50]) and calculation of in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI).

We used a cell-based assay as an alternative to animal testing to determine the toxicity of the selected compounds (27, 28). The cytotoxicity was evaluated in HepG2 cells (human hepatocellular carcinoma; ATCC HB-8065) maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), and 1× MEM amino acid solution (Sigma). Cell monolayers were detached using 1× trypsin/EDTA (Gibco), washed, and adjusted to 20,000 cells/well in 100 μl of supplemented DMEM. For evaluating the toxicity of 9-aminoacridines, we utilized mouse peritoneal macrophages due to the fact that HepG2 cells, like other hepatic (tumoral) cell lines, undergo apoptosis when exposed to this family of compounds (29). Peritoneal macrophages from uninfected mice were obtained as described above. The cells were washed twice by centrifugation and adjusted to 20,000 per 100 μl of supplemented MEM. Then, processing of both types of cells followed the same protocol. The cells were added to white-bottomed 96-well plates containing 100 μl of serial 2-fold dilutions of the test compounds (3.9 to 250 μM) or 2.5% DMSO as the control. After 24 h of culture at 37°C, the number of viable cells was determined by quantification of the ATP present in the cells using a Cell Titer-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega). The luminescence values were transformed to percentages of cytotoxicity compared to control levels, which allowed constructing a regression model to calculate the cytotoxic concentration that killed 50% of the cells (CC50) using GraphPad (Prism 5.0). At least 2 different assays were carried out to determine each molecule's IVTI, which was calculated as the ratio between the CC50 obtained in the HepG2 cell line or peritoneal macrophages and the corresponding EC50.

In vitro metabolic stability.

To estimate the metabolic stability of the compounds having IVTI > 100, we incorporated the mouse S9 fraction of liver enzymes (Moltox, Boone, NC) into both the HepG2 cytotoxicity assay and the ELEC assays according to the method developed by Otto and collaborators (30). The liver S9 fraction, which contains drug-metabolizing enzymes, including cytochrome P450, flavin monooxygenases, and UDP glucuronyl transferases, was prepared and kept on ice until use. The final concentration of this preparation was as follows: 0.4 mg S9 protein (Moltox, Boone, NC)/ml, 3.1 mM KCl, 6.3 mM G6P, and 1 mM NADPH (Sigma) in supplemented DMEM (ELEC) or MEM (HepG2 cells). Therefore, determination of the IVTI (CC50/EC50) upon incorporation of the S9 fraction into both HepG2 cells and ELEC allowed us to estimate the in vitro metabolic stability of compounds.

Drug likeness analysis.

We used the PubChem compound database to evaluate the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) filters addressing “druggability” (Lipinski's rule of five) (31) and “bioavailability” (32) to assist in the identification of the chemotypes that would best warrant future lead optimization and in vivo studies. We used the Chemical Structure Clustering Tool, which is freely available through PubChem, to identify FDA-approved compounds that had structures similar (>0.7 Tanimoto) (33) to those of our active compounds in the collections of phenothiazines and 9-aminoacridines.

RESULTS

Quantification of lymph node parasite load.

Infection of laboratory rodents with the Leishmania spp. that produce cutaneous disease is characterized by the initial replication of parasites in dermal phagocytes followed by trafficking of infected cells to, and expansion within, the draining lymph node (34–36). Therefore, we established a model of cutaneous L. major infection that enabled us to collect large numbers of infected cells from subiliac lymph nodes to use in the ELEC assay (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Following intradermal infection, there was a dramatic increase in the cellularity of the lymph nodes of infected animals by 14 days p.i., and the increased cellularity remained stable thereafter (Table 1). The parasite luminescent signal increased dramatically until peaking at 28 days p.i., indicating the replication of parasites within the lymph node during this time period (Table 1). This occurred despite a loss of luciferase plasmid in the amastigote population from day 14 to day 35 p.i., which was assessed by determining the luminescent signal in microscopically enumerated amastigotes (Table 1). The significant decline observed in amastigote luminescent signal over time was similar to previous observations (22) (B. L. Travi and P. C. Melby, unpublished data) but did not compromise the assay as long as the lymph node cells were collected no later than 4 weeks p.i. Regardless of the decline in luminescent signal, the amastigotes could be effectively quantified to evaluate antileishmanial efficacy using ELEC as long as the standard curve for quantification of amastigotes was generated from amastigotes derived from the same time point of infection within the same experiment. Taking into account the increase in LN cellularity and parasite burden, with the decline in luminescent signal per parasite over time (due to the expected rate of loss of the plasmid), we established the optimal time point for harvest of the LN for the ELEC assay at 21 to 28 days p.i.

TABLE 1.

Luminometric signals of L. major at different days postinfection, determined in the ex vivo lymph node explant culture- and tissue-derived amastigotes

| No. of days p.i. | Total no. of cells per mousea (×106) | P valueb | No. of RLUc per 105: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node cells | Amastigotes | |||

| Uninfected | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0 | ||

| 14 | 25.5 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 39 ± 17 | 2,973 ± 207 |

| 21 | 20.5 ± 2.5 | <0.001 | 175 ± 20 | 1,559 ± 73 |

| 28 | 20.4 ± 1.8 | <0.001 | 365 ± 19 | 484 ± 67 |

| 35 | 22.3 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | 50 ± 11 | 53 ± 5 |

Data represent the means ± standard errors of cell numbers obtained from subiliac lymph nodes of 3 animals at each time point.

P values represent comparisons between the numbers of lymph node cells in uninfected and infected animals at days 14, 21, 28, and 35 postinfection. The P values were calculated using the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparisons test.

Lymph node cells or amastigotes counted by light microscopy using a Neubauer chamber. Data represent the means ± standard errors of numbers of relative light units (RLU).

Alteration of lymph node cell populations of mice infected with L. major.

Microscopic and flow cytometry evaluations of the enlarged lymph nodes obtained from infected animals demonstrated that, after inoculation with Leishmania, there were significant changes in both cell densities and composition compared to those seen with the uninfected animals at 21 to 28 days p.i. (Table 2). We, like other authors (34–40), found a 5-to-20-fold total increase in the quantity of specific cell populations between 2 to 4 weeks p.i. (from 2 × 106 cells in uninfected mice to 35 × 106 cells in infected mice); those cell populations were composed of 14.7 × 106 B cells (CD45R+ B220+) (P = 0.0001), 11.3 × 106 CD4+ T cells (P < 0.0001; Table 2), 4.1 × 106 CD8+ T cells (P = 0.001; Table 2), and 1.6 × 106 phagocytes (dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils).

TABLE 2.

Altered lymph node cellularity in response to L. major infection

| Cell type/group | Total no. of cells (×106) per mousea |

Cell percentageb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected (n = 12 mice) | Infected (n = 15 mice) | P valuec | Uninfected (n = 12 mice) | Infected (n = 15 mice) | P valuec | |

| Total T cells (CD3+) | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 16.1 ± 5.4 | <0.001 | 68.7 ± 8.2 | 43.4 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| T CD4+ | 0.89 ± 0.6 | 11.3 ± 3.9 | <0.001 | 43.6 ± 8.2 | 30.6 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| T CD8+ | 0.38 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | <0.001 | 18.4 ± 4.5 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Other T cells (CD4− CD8−) | 0.16 ± 0.2 | 0.69 ± 1.8 | <0.01 | 6.6 ± 10.2 | 1.8 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| B lymphocytes (CD45R+/B220+) | 0.36 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 8.3 | <0.001 | 16.9 ± 7.0 | 38.5 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Myeloid cells (GR1+/Ly6G−) | 0.13 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 6.4 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | <0.01 |

| Other (not lymphocyte or myeloid) | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 5.0 | <0.001 | 11.5 ± 9.0 | 15.5 ± 13.8 | ns |

Data represent the means ± standard deviation of total cell numbers obtained from pooled subiliac lymph nodes of each animal obtained from uninfected and infected animals between days 21and 28 postinfection and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Data represent the mean percentages ± standard deviations of the percentages of cells obtained from same lymph node cells.

ns, nonsignificant differences. The P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test.

Optimization of lymph node cell number for determination of antileishmanial activity of compounds in ELEC.

Once we established the ideal time point for harvesting lymph node cells for the ELEC, we determined the range of cell densities that allowed good discrimination between the luminescent signals in ELECs exposed to antileishmanial compounds versus controls. For this purpose, 2-fold serial dilutions of lymph node cells ranging in number from 7.8 × 103 to 5 × 105 were exposed to 3 different known antileishmanial drugs. We found significant differences between treated wells and corresponding untreated controls at densities ≥ 6.25 × 104 cells per well (Table 3). Therefore, in experiments to screen compounds for antileishmanial activity and to determine the EC50 (see below), at least 62,000 cells were required, and by convention, we used 100,000 cells per well to ensure a strong luminescent signal. Using this level of cell density, the ELEC from a single infected mouse would enable screening of 26 compounds in triplicate.

TABLE 3.

Range of lymph node cells per well capable of detecting antileishmanial activity of standard compounds

| No. of cells per wella | Controlb RLUc (×102) | Miltefosine (2 μM) |

Pentamidine (1 μM) |

Amphotericin B (0.25 μM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLU (×102) | % reductiond | P valuee | RLU (×102) | % reduction | P value | RLU (×102) | % reduction | P value | ||

| 500,000 | 125.4 ± 1.4 | 46.7 ± 4.5 | 62.6 | <0.001 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 98.6 | <0.001 | 24.5 ± 1.5 | 80.4 | <0.001 |

| 250,000 | 106.7 ± 3.4 | 37.2 ± 1.4 | 65.2 | <0.001 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 98.8 | <0.001 | 19.7 ± 1.8 | 81.5 | <0.001 |

| 125,000 | 58.5 ± 5.6 | 21.3 ± 1.5 | 63.6 | <0.001 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 98.3 | <0.001 | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 82.2 | <0.001 |

| 62,500 | 17.7 ± 5.6 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 62.4 | <0.001 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 95.8 | <0.001 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 80.2 | <0.001 |

| 31,250 | 50.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 68.0 | ns | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 95.3 | <0.05 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 83.8 | ns |

| 15,625 | 23.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 66.5 | ns | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 97.0 | ns | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 85.8 | ns |

| 7,813 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 69.2 | ns | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 96.5 | ns | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 92.1 | ns |

Data represent numbers of cells counted by light microscopy using a Neubauer chamber. The cells were pooled from the subiliac lymph node of 3 infected animals at 21 days p.i.

Data represent untreated, infected lymph node negative-control cells obtained as explained in footnote a.

RLU (relative light unit) data represent the means ± standard deviations of the results of 3 replicate experiments.

Percent reduction of parasite burden with regard to controls was calculated as 100 − [(parasite counts in treated cells/parasite counts in untreated cells) × 100].

P values were calculated using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni posttest.

Ex vivo lymph node explant cultures support the replication of L. major amastigotes.

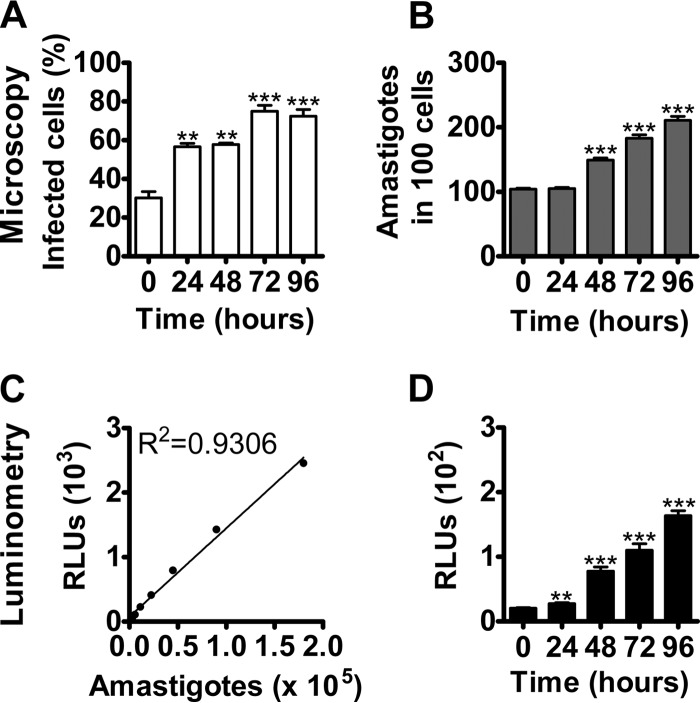

In order to utilize ELEC for screening antileishmanial compounds, it was important to determine that it supported parasite proliferation. Microscopic and luminometric evaluations indicated that after 48 h of ex vivo culture of the LN explant, there was a significant increase in the percentage of infected phagocytes and number of amastigotes per cell (Fig. 1). Regression analysis of the microscopic quantification and luminometric signal of amastigotes harvested from lymph nodes validated the utilization of luciferase-transfected L. major (R2 = 0.9306; P = 0.0007) to estimate parasite burdens in ELEC (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG 1.

Ex vivo-cultured lymph node explants support L. major replication. The L. major ex vivo model system was validated regarding parasite multiplication, as determined by microscopy and luminometry. The panels correspond to representative ex vivo explant cultures of 2 independent experiments of L. major obtained from mouse lymph nodes at 21 days p.i. (A) Mean percentages ± standard errors of infected lymph node cells after 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of culture. The plated cells were stained with Giemsa and the proportions of infected cells determined by microscopy. (B) Means ± standard errors of amastigote numbers per 100 infected cells, determined by microscopic enumeration of Giemsa-stained lymph node explants over 96 h. (C) Standard curve of amastigotes isolated in 2 different experiments from lymph nodes of mice at 21 days postinfection with L. major. The amastigotes were counted by light microscopy using a Neubauer chamber and the corresponding relative light units (RLUs) determined by luminometry. (D) Means ± standard errors of relative light units (RLU) representing parasites from infected lymph node cells after 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of ex vivo culture. P value significance levels: *, < 0.05; **, < 0.01; ***, < 0.001. The statistical significance of the data shown in panels A, B, and D was determined using the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparisons test. The statistical significance of the data shown in panel C was determined using linear regression analysis.

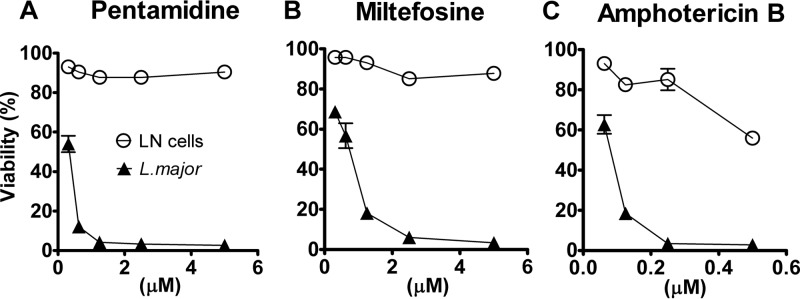

Drug-induced reduction in parasite load in ELEC due to specific antileishmanial activity.

It was necessary to establish whether or not the decrease in parasite burden detected after exposing the ELECs to antileishmanial drugs was due to a general toxic effect, i.e., through the killing of amastigote-laden host cells. To exclude this possibility, we developed dose-response curves for antileishmanial efficacy levels by luminometry and host cell toxicity determinations using the trypan blue exclusion test. These assays demonstrated that pentamidine, miltefosine, and amphotericin B (drugs currently used to treat leishmaniasis) killed intracellular L. major with little toxic effect on the host cells, even at doses much higher than the respective antileishmanial EC50 levels (Fig. 2). Consequently, the lack of correlation between leishmanicidal efficacy and cytotoxicity (Spearman correlation P > 0.05) showed that a reliable measure of specific antileishmanial activity could be determined in the ELEC assay.

FIG 2.

Lymph node cell and Leishmania viability in response to established antileishmanial drugs. Percent viability of L. major and lymph node cells in ELEC treated with pentamidine (A), miltefosine (B), and amphotericin B (C) was determined in lymph node explants from mouse infected for 21 days with L. major and cultured ex vivo for 48 h. The luciferase luminescent signal was used to determine parasite viability, and the viability of lymph node cells was assessed by microscopy using trypan blue exclusion. The percentage of parasite viability with regard to controls was calculated as (parasite counts in treated cells/parasite counts in untreated cells) × 100. The percentage of viable cells was calculated as (total number of viable cells per ml of aliquot/total number of cells per ml of aliquot) × 100. Results are shown as the mean percentages ± standard errors of the means of data from a single representative experiment.

Antileishmanial activity in ELEC correlates with activity in an in vitro macrophage infection model.

Once it was proven that ELEC was suitable for determinations of antileishmanial activity, we compared this system to the commonly used in vitro model of infected peritoneal macrophages. Eleven compounds, demonstrated previously to have activity against L. donovani (21) and including drugs currently used to treat leishmaniasis, were evaluated in mouse peritoneal macrophages infected in vitro with L. major and were compared with ELEC (Table 4). Analyses of the EC50 data from ELEC and peritoneal macrophages indicated that the results of the assays were concordant (R2 = 0.9273; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7282 to 0.9821; P = 0.0001) and that the results of the paired assays, when considered as a group, were not different (Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test P = 0.4648; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparative efficacy (EC50) of compounds with antileishmanial activity in the ex vivo lymph node system or in macrophages infected with promastigotes of L. major

| Compound | Avg (SE) EC50 (μM) in RLUa |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ex vivo lymph node cells | Peritoneal macrophages | |

| Amphotericin B | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.01) |

| Miltefosine | 1.96 (0.21) | 1.71 (0.47) |

| Pentamidine | 0.72 (0.29) | 2.49 (1.38) |

| Quinacrine | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.85 (0.01) |

| Antimycin A | 0.45 (0.07) | 1.00 (0.92) |

| Disulfiram | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.11) |

| Monensin A | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.38 (0.10) |

| Nortriptyline | 8.11 (4.05) | 5.73 (1.94) |

| Securinine | 5.1 (0.8) | 5.00 (1.35) |

| Tilorone | 2.76 (1.56) | 2.55 (2.65) |

| Tetrandrine | 0.88 (0.83) | 3.57 (0.33) |

Data represent the means ± standard errors of EC50s expressed in relative light units (RLU) from 2 or 3 different experiments performed using lymph node cells from infected animals (ex vivo) or peritoneal macrophages from in vitro infections (see details in Materials and Methods). The EC50 was determined by regression analysis using GraphPad (Prism 5.0) software.

Identification of compounds with activity against L. major.

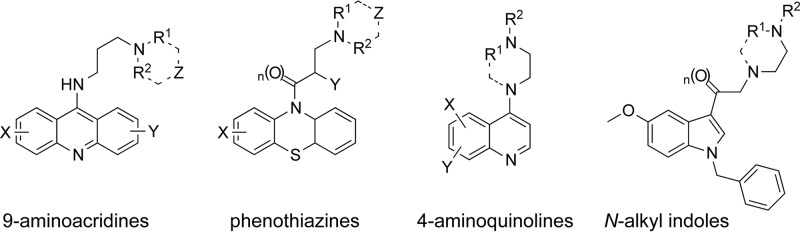

A collection of 334 compounds, which included several molecules shown previously to have antileishmanial activity (21), were arranged in 9 small libraries according to their general chemotypes. As expected, the inclusion of several molecules with known activity against another species of Leishmania (L. donovani) resulted in a high proportion of hits. In the ELEC screen, we identified 119 (35%) compounds, designated hits, that inhibited parasite viability >50% at 2.5 μM compared to the unexposed control (average of 3 wells) (Table 5; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). The average assay window for ELEC was 60.5 and the average Z′ value was 0.76, indicating that this system is adequate to be used for hit identification in a medium-throughput format (26). Eighty-five percent (101/119) of the primary hits were confirmed to be true hits by means of EC50 determinations (Table 5), with some of them (n = 19) showing efficacy at a concentration of <1 μM. In parallel to the determination of antileishmanial activity, we quantified the level of cellular cytotoxicity of the hits using an established dose response assay in a human hepatocyte cell line (27, 28, 41) to calculate the concentration of the compound that killed 50% of the cells (CC50). Taking the ratio of the cytotoxicity to the antileishmanial activity, we calculated the in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI = CC50/EC50) as an estimate of potential drug efficacy. Of the 101 active molecules, 24 (7%) were highly active, with IVTI > 100. Seventy-one compounds were demonstrated to be cytotoxic (CC50 ≤ 30 μM) and therefore were excluded from the calculations that determined the IVTI. PubMed and PubChem searches (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) of the 24 highly active compounds revealed that 7 molecules were reported to have anti-infective activity in vitro against different pathogens (Leishmania sp., Plasmodium falciparum, Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, Salmonella sp., and Giardia sp.) (see details in Table 6). Perhaps more importantly, several analogs in the top 24 fall into readily recognized classes of compounds, giving preliminary validation to the hypothesis that these scaffolds could serve as valuable leads for additional medicinal chemistry optimization (Fig. 3). These include N-alkyl indoles (13%; 3/24) as well as 4-aminoquinolines (13%; 3/24) and closely related analogs of 9-aminoacridines (17%; 4/24) and phenothiazines.

TABLE 5.

Numbers of compounds identified as hits through screening at 2.5 μM or by EC50 determination using the ex vivo lymph node explant culture

| Chemical class | n | No. of compounds |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hits (>50% inhibition) | EC50 ≤ 2.5 μM | % concordance | ||

| Quinolines | 99 | 34 | 29 | 85 |

| Thiuram disulfides | 7 | 7 | 6 | 85 |

| Fluorenones | 13 | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| Indoles | 54 | 13 | 7 | 54 |

| Benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3-diones | 14 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 9-aminoacridines | 10 | 8 | 5 | 63 |

| Indene-diones and acetophenones | 10 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Phenothiazines | 81 | 16 | 16 | 100 |

| VLa Leads | 46 | 33 | 30 | 91 |

| Total | 334 | 119 | 101 | 85 |

VL Leads are compounds in a collection previously identified as effective against Leishmania donovani in a drug screening for visceral leishmaniasis.

TABLE 6.

Efficacy and metabolic stability of compounds with a high in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI > 100) as determined in the ex vivo lymph node explant culture of L. major before and after the addition of the S9 fraction of liver enzymesa

| CID | No S9 |

Addition of S9 |

Antimicrobial activityb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 (μM) | EC50 (μM) | IVTI | CC50 (μM) | EC50 (μM) | IVTI | ||

| Indoles | |||||||

| 1825522 | 301.1 ± 45.5 | 2.22 ± 0.7 | 135.4 | 290.7 ± 25.8 | 5.7 ± 5.3 | 50.3 | None |

| 3927860 | 485.8 ± 30.7 | 4.30 ± 2.1 | 112.9 | 268.9 ± 15.1 | 8.74 ± 1.0 | 30.8 | None |

| 990853 | 266.4 ± 15.9 | 2.55 ± 0.2 | 104.5 | 153.6 ± 5.7 | 1.58 ± 0.5 | 97.3 | Trypanosoma cruzi |

| Thiuram disulfides | |||||||

| 7188 | 31.3 ± 3.3 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 700.8 | 51.3 ± 3.1 | 0.15 ± 0.0 | 333.3 | None |

| 3117 | 38.1 ± 1.4 | 0.06 ± 0.0 | 661.4 | 44.9 ± 5.8 | 0.06 ± 0.0 | 801.2 | Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania major, Giardia lamblia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| 95876 | 139.6 ± 12.7 | 0.64 ± 0.0 | 219.6 | 119.4 ± 4.2 | 2.05 ± 0.3 | 58.2 | None |

| Phenothiazines | |||||||

| 44657026 | 284.9 ± 6.1 | 0.19 ± 0.0 | 1,486.7 | 371.1 ± 0.2 | 1.26 ± 0.2 | 294.5 | None |

| 2897584 | 102.2 ± 13.2 | 1.00 ± 0.2 | 101.7 | 137.1 ± 13.2 | 2.21 ± 0.2 | 62.0 | None |

| VL Leads | |||||||

| 14957 | 58.4 ± 4.9 | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 1,772.1 | 54.4 ± 12.9 | 0.02 ± 0.0 | 2,536.7 | Plasmodium falciparum |

| 23681158 | 34.3 ± 1.3 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 948.1 | 160.12 ± 2.6 | 0.65 ± 0.1 | 246.8 | None |

| 359473 | 32.4 ± 4.7 | 0.17 ± 0.1 | 193.6 | 193.5 ± 5.5 | 1.08 ± 0.1 | 180.0 | None |

| 31239 | 37.6 ± 2.3 | 0.22 ± 0.3 | 172.2 | 24.9 ± 1.4 | 0.17 ± 0.0 | 143.7 | None |

| 15865 | 38.6 ± 3.4 | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 156.4 | 186.0 ± 10.8 | 1.66 ± 0.1 | 112.0 | None |

| 11980056 | 37.1 ± 9.3 | 0.24 ± 0.1 | 155.2 | 37.6 ± 2.3 | 0.73 ± 0.1 | 51.9 | None |

| 1732 | 138.2 ± 8.2 | 0.99 ± 0.1 | 138.3 | 40.3 ± 10.5 | 0.86 ± 0.1 | 47.0 | None |

| 5702238 | 53.2 ± 3.1 | 0.43 ± 0.1 | 124.4 | 46.3 ± 4.1 | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 44.8 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium |

| 73078 | 31.4 ± 9.0 | 0.30 ± 0.2 | 104.8 | 36.7 ± 3.9 | 1.42 ± 0.2 | 25.9 | Plasmodium falciparum |

| Quinolines | |||||||

| 4096842-Q | 210.5 ± 3.8 | 0.89 ± 0.1 | 237.1 | 348.7 ± 8.5 | 4.65 ± 0.5 | 75.0 | None |

| 725471-4AQ | 59.4 ± 3.7 | 0.32 ± 0.0 | 183.8 | 97.9 ± 6.5 | 5.84 ± 0.8 | 16.8 | None |

| 1022078-4AQ | 57.2 ± 2.0 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 132.2 | 152.9 ± 9.1 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 4,368.6 | None |

| 9-Aminoacridines | |||||||

| 14169 | 36.8 ± 1.2 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 770.2 | 58.3 ± 1.8 | 0.25 ± 0.0 | 235.9 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Plasmodium falciparum, Trypanosoma cruzi |

| 3131604 | 128.8 ± 3.4 | 0.35 ± 0.0 | 366.7 | 147.5 ± 4.2 | 0.42 ± 0.0 | 350.9 | None |

| 3122093 | 58.9 ± 1.4 | 0.28 ± 0.2 | 208.2 | 65.2 ± 1.9 | 0.11 ± 0.0 | 583.2 | None |

| 2790597 | 92.9 ± 2.5 | 0.49 ± 0.1 | 188.8 | 115.4 ± 3.4 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 227.8 | Leishmania major |

EC50 and CC50 data represent the means ± standard errors of the results of 2 or 3 different experiments carried out with or without exposure to S9 (hepatic metabolic enzymes). Luminescence was used to calculate the effective concentration (EC50) in the L. major ex vivo model. The cytotoxicity (CC50) was determined using the HepG2 cell line. The IVTI of each compound was calculated as the ratio between the CC50 obtained in the HepG2 cell line and the corresponding EC50.

Antimicrobial activity as reported by Pubchem bioassays.

FIG 3.

Representative drug-like chemotypes with antileishmanial activity as determined in the ex vivo lymph node explant culture of L. major.

Assessment of lead compound metabolic stability.

Compound stability is an essential characteristic of therapeutic molecules and has a significant role in directing which active molecules are selected to move forward to in vivo preclinical trials. In order to estimate the metabolic stability of molecules in ELEC, we incorporated the S9 liver enzyme fraction, which contains the drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450, flavin monooxygenases, and UDP glucuronyl transferases, into the ELEC culture medium. Using this approach, we were able to discriminate between molecules with good or poor in vitro metabolic stability. Not unexpectedly, a high proportion of molecules showed decreased antileishmanial activity upon exposure to liver enzymes. Fourteen of 24 molecules (58%) lost ≥2-fold activity, and yet 5 of these molecules still had an EC50 of ≤1 μM (Table 6). Five compounds showed improvement in the IVTI; 2 of these (PubChem compound identification no. [CID] 1022078 and 3122093) showed improved EC50 after the S9 exposure, while the others, such as disulfiram (CID 3117), showed higher IVTI because of reduced cytotoxicity and virtually no change in EC50 after exposure to liver enzymes. The rest of the compounds had a reduced IVTI after exposure to the hepatic enzymes (Table 6).

Drug likeness analysis.

To assess drug likeness, we examined the physical and chemical properties listed in the PubChem compound database for the compounds active against L. major (IVTI > 100). We considered that the chemical property filters addressing druggability (Lipinski's rule of five) (31) and bioavailability (32) would be useful to assist in the identification of chemotypes with the best potential to exhibit good in vivo properties. The druggability filter is based on the observation that most drugs that can be effectively administered by the oral route have a molecular weight ≤ 500, an octanol-water partitioning coefficient (LogP) ≤ 5, five or fewer hydrogen bond donor sites, and 10 or fewer hydrogen bond acceptor sites (N and O atoms) (31). The bioavailability filter considers the five factors related to druggability and also includes the polar surface area (≤200 is favorable), defined as the sum of all the surface contributions of polar fragments, and the number of fused aromatic rings (≤5 is favorable) of the compound (42, 43). This filter was shown previously to correlate with passive compound transport through membranes (44). For a compound to be predicted to pass this filter, it must fulfill the requirements for 6 of the 7 properties examined (32). A number of compounds (14 of 24) with a high IVTI (>100) passed the druggability and bioavailability filters (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), indicating that they had properties that warrant their further investigation and optimization. We found concordance between the filters' prediction of good druggability and bioavailability of the thiuram disulfide analogs (CID 7188, 3177, and 95876) and the high oral absorption reported in the literature and PubChem for the thiuram disulfide disulfiram (CID 3117), which has had extensive clinical use. In support of the potential value of using the filters to predict the bioavailability of the test compounds of phenothiazines and 9-aminoacridines, we found that the Chemical Structure Clustering Tool identified FDA-approved compounds that had structures similar (>0.7 Tanimoto) (33) to our active compounds. Regarding the tricyclic compound (CID 2897584), we calculated a significant similarity score of 0.806 with chlorpromazine (CID 2726) and a significant similarity score of 0.979 for CID 44657026 with the compound moricizine (CID 34633), both of which are known to be bioavailable. We observed a similar trend with the 9-aminoacridines CID 14169, CID 3131604, and CID 2790597 and the bioavailable reference compound quinacrine (CID 2725002) (Tanimoto Substructure Fingerprint similarity score 0.652 to 0.711). While the filters indicated that CID 31239, CID 15865, CID 1732, and CID 5702238 are druggable compounds, medicinal chemistry expertise indicates that these surfactants and topical disinfectants would not be appropriate for oral formulation. These results stress the fact that in silico predictive tools have to be considered complementary tools to established medicinal chemistry knowledge during hit and lead selection.

DISCUSSION

We developed a new ex vivo experimental model for drug discovery for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. major through which we identified lead compounds that have antileishmanial activity at a concentration of <1 μM. This model utilizes lymph node cells of mice that were infected with a strain of L. major that had been episomally transfected with the luciferase gene, allowing rapid parasite quantification in a medium-throughput format. Additionally, with this approach the efficacy of test compounds is determined within a physiological and immunological environment similar to that of the infection site. Furthermore, the ease of establishing a large number of ex vivo explant cultures from a single infected mouse with a minimum amount of manipulation, with avoidance of the time-consuming and operator-biased quantification of parasites by microscopy (21, 45, 46), offers a substantial advantage over the labor-intensive in vitro macrophage infection model. Since the ex vivo system includes the intracellular amastigote stage, it also avoids the use of the insect stage promastigotes, whose susceptibility to antileishmanial compounds correlates poorly with the susceptibility of the more human-relevant intracellular amastigotes (15, 45, 47–50).

Our ex vivo system, comprised of macrophages, fibroblasts, and lymphocytes, provides a model that enables the evaluation of compounds for antileishmanial activity in the presence of host immune cells and their secreted cytokines, which can profoundly influence parasite killing, leading to inadequate calculations of compound efficacy (19, 20, 46, 51, 52). In fact, several currently used antileishmanial drugs are known have efficacy that is influenced by the host immune response (19, 20, 51, 52). Additionally, the approach meets all the requirements of a valid cell-based screening systems for antileishmanial compounds as described by Croft (53), which included (i) the use of mammalian stages of the parasite, (ii) multiplying parasite populations, (iii) quantifiable and reproducible measurement of drug activity, and (iv) confirmed activity of standard drugs in concentrations achievable in serum/tissues.

Similar to other luciferase-transfected microorganisms, our Leishmania strain progressively lost the luciferase plasmid over time due to the absence of the selective antibiotic pressure (G418) during L. major expansion within the infected mouse (22). Therefore, the significant signal decline at 35 days p.i. indicated that lymph node cells should be collected no later than 4 weeks p.i. to clearly discriminate between drug-exposed and control wells. Another consideration regarding signal discrimination referred to the number of cells; although our plate luminometer (FLUOstar Omega; BMG Labtech) required >10,000 cells to reproducibly obtain an adequate signal difference(s) in a medium-throughput format, it is likely that cell numbers will have to be adjusted according to the sensitivity of different luminometers.

Using microscopy and luminometry methodologies, we found that, starting at 48 h of culture, ELEC supported parasite proliferation, with a significant increase in the percentage of infected phagocytes and number of amastigotes per cell. This is critical since activity of a drug should be assessed in a system that supports actively replicating parasites. The reported excellent correlation between luminometry and the number of amastigotes supports the consistency of data obtained with our system. A potential caveat for ELEC is that some compounds could inhibit light emission by preventing luciferase transcription or enzyme activity or by drug binding to the substrate (luciferin). These possibilities are diminished by the removal of the supernatant containing the drug and the excess of luciferin added to the cells prior to the luminometry reading. Furthermore, none of our compounds was identified as an inhibitor of the luciferase reaction through a search of the published literature.

The ELEC showed to be a useful medium-throughput system for hit identification, since, according to the EC50 determinations, 85% of the hit compounds were confirmed to have antileishmanial activity. The comparison of the antileishmanial activities of drugs used to treat leishmaniasis that were tested in the ELEC system and in peritoneal macrophages infected in vitro with promastigotes indicated congruence between the two methods. However, peritoneal macrophages obtained by lavage lack the interaction with lymphocytes and the polarization (M1 or M2) by environmental signals that would occur at the site of infection and could ultimately impact on compound efficacy, particularly when drugs require the participation of the immune system to clear Leishmania.

Incorporation of the S9 liver enzyme fraction into ELEC allowed estimation of the antileishmanial activity following exposure to metabolic enzymes. In fact, a high proportion of molecules showed decreased IVTI due to a diminution of the antileishmanial activity or (to a lesser extent) an increase in toxicity, indicating that, before preclinical studies are undertaken, active and nontoxic compounds would have to be protected against hepatic metabolism using pharmacological or medicinal chemistry approaches.

A more in-depth analysis of our top 24 hits for suitability as lead compounds for additional medicinal chemistry optimization was performed. As with most small-molecule screens, when several hits fall into the same structural category, they are generally prioritized toward further optimization. Thus, as mentioned previously, we identified several structurally similar analogs that fall into three broad classifications, including N-alkyl indoles, 4-aminoquinolines, and 9-aminoacridines. Overall, these analogs are viewed as amenable to further optimization based on low average molecular weight, synthetic tractability, and reasonable physiochemical properties (LogP, polar surface area, and adherence to Lipinski's rules). Additional evidence that the quinoline and 9-aminoacridine hits identified in the ELEC system are particularly good leads for further development is based on previous studies of these compounds as potential antimalarial compounds. Here it was shown that these relatively basic compounds with high LogP (lipophilicity) values favor their intracellular transport, which is responsible for the observed activity and selectivity (54–57). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that certain acridines (54, 58–61) can inhibit DNA synthesis in Leishmania and/or Plasmodium, interfering with DNA transcription (topoisomerase II). Other compounds from our screen such as cetylpyridinium chloride (CID 31239), classified as a quaternary ammonium surfactant, may have potential to be developed in topical formulations for the treatment of leishmaniasis. The microbicidal activity of these types of compounds is related to the leakage of cellular contents due to the disruption of intermolecular interactions at the cell membrane bilayers. However, several other analogs that fall outside the classifications mentioned above are, we believe, less suitable as leads for further development. This comprises compounds that contain reactive functional groups, including aldehydes (CID 14957), Michael acceptors (CID 359473), and thiuram disulfides (CID 7188, 3177, and 95876), that are less-than-ideal starting points for further optimization.

The drug likeness filters, which are based on evaluation of the physical and chemical properties of a molecule, are useful tools to help prioritize compounds for lead optimization studies to improve in vivo properties. It is also likely that significant improvements in antileishmanial activity could be achievable through chemical optimization guided by the ELEC assay. Other compounds identified herein may require optimization to address the metabolic liabilities suggested by their reduced activity after exposure to the S9 liver enzyme fraction. Overall, the ELEC assay served to identify synthetically approachable and generally drug-like compounds that possess antileishmanial activity in a cellular context relevant to human disease. Further chemical optimization of the best of these leads appears warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Department of Defense, Air Force contract no. AF-SGR-8-31-09 (B.L.T., principal investigator [P.I.]). The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 October 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00887-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desjeux P. 2004. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:305–318. 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Maguire JH, Alvar J. 2008. Complexities of assessing the disease burden attributable to leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2:e313. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvar J, Yactayo S, Bern C. 2006. Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol. 22:552–557. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli L. 2007. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:1018–1027. 10.1056/NEJMra064142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morel CM. 2003. Neglected diseases: under-funded research and inadequate health interventions. Can. we change this reality? EMBO Rep. 4(Spec No):S35–S38. 10.1038/sj.embor.embor851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Sivakumar R. 2004. Challenges and new discoveries in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Chemother. 10:307–315. 10.1007/s10156-004-0348-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palumbo E. 2009. Current treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis: a review. Am. J. Ther. 16:178–182. 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181822e90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amato VS, Tuon FF, Imamura R, Abegão de Camargo R, Duarte MI, Neto VA. 2009. Mucosal leishmaniasis: description of case management approaches and analysis of risk factors for treatment failure in a cohort of 140 patients in Brazil. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 23:1026–1034. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreira W, Leprohon P, Ouellette M. 2011. Tolerance to drug-induced cell death favours the acquisition of multidrug resistance in Leishmania. Cell Death Dis. 2:e201. 10.1038/cddis.2011.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beveridge E, Caldwell IC, Latter VS, Neal RA, Udall V, Waldron MM. 1980. The activity against Trypanosoma cruzi and cutaneous leishmaniasis, and toxicity, of moxipraquine (349C59). Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74:43–51. 10.1016/0035-9203(80)90010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäntylä A, Garnier T, Rautio J, Nevalainen T, Vepsälainen J, Koskinen A, Croft SL, Järvinen T. 2004. Synthesis, in vitro evaluation, and antileishmanial activity of water-soluble prodrugs of buparvaquone. J. Med. Chem. 47:188–195. 10.1021/jm030868a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori K, Kawano M, Fuchino H, Ooi T, Satake M, Agatsuma Y, Kusumi T, Sekita S. 2008. Antileishmanial compounds from Cordia fragrantissima collected in Burma (Myanmar). J. Nat. Prod. 71:18–21. 10.1021/np070211i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inocêncio da Luz RA, Vermeersch M, Deschacht M, Hendrickx S, Van Assche T, Cos P, Maes L. 2011. In vitro and in vivo prophylactic and curative activity of the triterpene saponin PX-6518 against cutaneous Leishmania species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:350–353. 10.1093/jac/dkq444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nwaka S, Hudson A. 2006. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5:941–955. 10.1038/nrd2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharlow ER, Close D, Shun T, Leimgruber S, Reed R, Mustata G, Wipf P, Johnson J, O'Neil M, Grögl M, Magill AJ, Lazo JS. 2009. Identification of potent chemotypes targeting Leishmania major using a high-throughput, low-stringency, computationally enhanced, small molecule screen. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e540. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siqueira-Neto JL, Song OR, Oh H, Sohn JH, Yang G, Nam J, Jang J, Cechetto J, Lee CB, Moon S, Genovesio A, Chatelain E, Christophe T, Freitas-Junior LH. 2010. Antileishmanial high-throughput drug screening reveals drug candidates with new scaffolds. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e675. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker RG, Thomson G, Malone K, Nowicki MW, Brown E, Blake DG, Turner NJ, Walkinshaw MD, Grant KM, Mottram JC. 2011. High throughput screens yield small molecule inhibitors of Leishmania CRK3:CYC6 cyclin-dependent kinase. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1033. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabors GS, Farrell JP. 1996. Successful chemotherapy in experimental leishmaniasis is influenced by the polarity of the T cell response before treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 173:979–986. 10.1093/infdis/173.4.979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray HW, Oca MJ, Granger AM, Schreiber RD. 1989. Requirement for T cells and effect of lymphokines in successful chemotherapy for an intracellular infection. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Invest. 83:1253–1257. 10.1172/JCI114009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray HW, Delph-Etienne S. 2000. Roles of endogenous gamma interferon and macrophage microbicidal mechanisms in host response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 68:288–293. 10.1128/IAI.68.1.288-293.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osorio Y, Travi BL, Renslo AR, Peniche AG, Melby PC. 2011. Identification of small molecule lead compounds for visceral leishmaniasis using a novel ex vivo splenic explant model system. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e962. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy G, Dumas C, Sereno D, Wu Y, Singh AK, Tremblay MJ, Ouellette M, Olivier M, Papadopoulou B. 2000. Episomal and stable expression of the luciferase reporter gene for quantifying Leishmania spp. infections in macrophages and in animal models. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 110:195–206. 10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00270-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacks DL, Hieny S, Sher A. 1985. Identification of cell surface carbohydrate and antigenic changes between noninfective and infective developmental stages of Leishmania major promastigotes. J. Immunol. 135:564–569 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strober W. 2001. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 21:A.3B.1–A.3B.2. 10.1002/0471142735.ima03bs21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel JC, Ang KK, Chen S, Arkin MR, McKerrow JH, Doyle PS. 2010. Image-based high-throughput drug screening targeting the intracellular stage of Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas' disease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3326–3334. 10.1128/AAC.01777-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gubler H. 2009. Assay data quality assessment. Methods Mol. Biol. 552:79–95. 10.1007/978-1-60327-317-6_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoonen WG, de Roos JA, Westerink WM, Débiton E. 2005. Cytotoxic effects of 110 reference compounds on HepG2 cells and for 60 compounds on HeLa, ECC-1 and CHO cells. II mechanistic assays on NAD(P)H, ATP and DNA contents. Toxicol. In Vitro 19:491–503. 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerets HH, Hanon E, Cornet M, Dhalluin S, Depelchin O, Canning M, Atienzar FA. 2009. Selection of cytotoxicity markers for the screening of new chemical entities in a pharmaceutical context: a preliminary study using a multiplexing approach. Toxicol. In Vitro 23:319–332. 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian ZY, Xie SQ, Mei ZH, Zhao J, Gao WY, Wang CJ. 2009. Conjugation of substituted naphthalimides to polyamines as cytotoxic agents targeting the Akt/mTOR signal pathway. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7:4651–4660. 10.1039/b912685f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otto M, Hansen SH, Dalgaard L, Dubois J, Badolo L. 2008. Development of an in vitro assay for the investigation of metabolism-induced drug hepatotoxicity. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 24:87–99. 10.1007/s10565-007-9018-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. 2001. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46:3–26. 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin YC. 2005. A bioavailability score. J. Med. Chem. 48:3164–3170. 10.1021/jm0492002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godden JW, Xue L, Bajorath J. 2000. Combinatorial preferences affect molecular similarity/diversity calculations using binary fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficients. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 40:163–166. 10.1021/ci990316u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraille E, De Trez C, Pajak B, Torrentera FA, De Baetselier P, Leo O, Carlier Y. 2003. Amastigote load and cell surface phenotype of infected cells from lesions and lymph nodes of susceptible and resistant mice infected with Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 71:2704–2715. 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2704-2715.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barthelmann J, Nietsch J, Blessenohl M, Laskay T, van Zandbergen G, Westermann J, Kalies K. 2012. The protective Th1 response in mice is induced in the T-cell zone only three weeks after infection with Leishmania major and not during early T-cell activation. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 201:25–35. 10.1007/s00430-011-0201-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carvalho LP, Petritus PM, Trochtenberg AL, Zaph C, Hill DA, Artis D, Scott P. 2012. Lymph node hypertrophy following Leishmania major infection is dependent on TLR9. J. Immunol. 188:1394–1401. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inaba K, Pack M, Inaba M, Sakuta H, Isdell F, Steinman RM. 1997. High levels of a major histocompatibility complex II-self peptide complex on dendritic cells from the T cell areas of lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 186:665–672. 10.1084/jem.186.5.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskay T, Wittmann I, Diefenbach A, Röllinghoff M, Solbach W. 1997. Control of Leishmania major infection in BALB/c mice by inhibition of early lymphocyte entry into peripheral lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 158:1246–1253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solbach W, Laskay T. 2000. The host response to Leishmania infection. Adv. Immunol. 74:275–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu AC, Scott P. 2007. Leishmania mexicana infection induces impaired lymph node expansion and Th1 cell differentiation despite normal T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 179:8200–8207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dambach DM, Andrews BA, Moulin F. 2005. New technologies and screening strategies for hepatotoxicity: use of in vitro models. Toxicol. Pathol. 33:17–26. 10.1080/01926230590522284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Looker DL, Martinez S, Horton JM, Marr JJ. 1986. Growth of Leishmania donovani amastigotes in the continuous human macrophage cell line U937: studies of drug efficacy and metabolism. J. Infect. Dis. 154:323–327. 10.1093/infdis/154.2.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritchie TJ, Macdonald SJ, Young RJ, Pickett SD. 2011. The impact of aromatic ring count on compound developability: further insights by examining carbo- and hetero-aromatic and -aliphatic ring types. Drug Discov. Today 16:164–171. 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linnankoski J, Ranta VP, Yliperttula M, Urtti A. 2008. Passive oral drug absorption can be predicted more reliably by experimental than computational models—fact or myth. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 34:129–139. 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fumarola L, Spinelli R, Brandonisio O. 2004. In vitro assays for evaluation of drug activity against Leishmania spp. Res. Microbiol. 155:224–230. 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacks D, Anderson C. 2004. Re-examination of the immunosuppressive mechanisms mediating non-cure of Leishmania infection in mice. Immunol. Rev. 201:225–238. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ephros M, Bitnun A, Shaked P, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. 1999. Stage-specific activity of pentavalent antimony against Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:278–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valiathan R, Dubey ML, Mahajan RC, Malla N. 2006. Leishmania donovani: effect of verapamil on in vitro susceptibility of promastigote and amastigote stages of Indian clinical isolates to sodium stibogluconate. Exp. Parasitol. 114:103–108. 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vermeersch M, da Luz RI, Toté K, Timmermans JP, Cos P, Maes L. 2009. In vitro susceptibilities of Leishmania donovani promastigote and amastigote stages to antileishmanial reference drugs: practical relevance of stage-specific differences. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3855–3859. 10.1128/AAC.00548-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pérez-Cordero JJ, Lozano JM, Cortés J, Delgado G. 2011. Leishmanicidal activity of synthetic antimicrobial peptides in an infection model with human dendritic cells. Peptides 32:683–690. 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray HW, Granger AM, Mohanty SK. 1991. Response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: T cell-dependent but interferon-gamma- and interleukin-2-independent. J. Infect. Dis. 163:622–624. 10.1093/infdis/163.3.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander J, Carter KC, Al-Fasi N, Satoskar A, Brombacher F. 2000. Endogenous IL-4 is necessary for effective drug therapy against visceral leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2935–2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Croft SL. 1986. In vitro screens in the experimental chemotherapy of leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis. Parasitol. Today 2:64–69. 10.1016/0169-4758(86)90157-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Giorgio C, Delmas F, Filloux N, Robin M, Seferian L, Azas N, Gasquet M, Costa M, Timon-David P, Galy JP. 2003. In vitro activities of 7-substituted 9-chloro and 9-amino-2-methoxyacridines and their bis- and tetra-acridine complexes against Leishmania infantum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:174–180. 10.1128/AAC.47.1.174-180.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Solomon VR, Haq W, Puri SK, Srivastava K, Katti SB. 2006. Design, synthesis and antimalarial activity of a new class of iron chelators. Med. Chem. 2:133–138. 10.2174/157340606776056179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fuertes MA, Nguewa PA, Castilla J, Alonso C, Pérez JM. 2008. Anticancer compounds as leishmanicidal drugs: challenges in chemotherapy and future perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 15:433–439. 10.2174/092986708783503221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez-Pineiro R, Burgos A, Jones DC, Andrew LC, Rodriguez H, Suarez M, Fairlamb AH, Wishart DS. 2009. Development of a novel virtual screening cascade protocol to identify potential trypanothione reductase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 52:1670–1680. 10.1021/jm801306g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Werbovetz KA, Lehnert EK, Macdonald TL, Pearson RD. 1992. Cytotoxicity of acridine compounds for Leishmania promastigotes in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:495–497. 10.1128/AAC.36.2.495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Werbovetz KA, Spoors PG, Pearson RD, Macdonald TL. 1994. Cleavable complex formation in Leishmania chagasi treated with anilinoacridines. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 65:1–10. 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mesa-Valle CM, Castilla-Calvente J, Sanchez-Moreno M, Moraleda-Lindez V, Barbe J, Osuna A. 1996. Activity and mode of action of acridine compounds against Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:684–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chauhan N, Vidyarthi AS, Poddar R. 2012. Comparative analysis of different DNA-binding drugs for leishmaniasis cure: a pharmacoinformatics approach. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 80:54–63. 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.