Abstract

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is caused by the opportunistic fungi Candida albicans and is prevalent in immunocompromised patients, individuals with dry mouth, or patients with prolonged antibiotic therapies that reduce oral commensal bacteria. Human salivary histatins, including histatin 5 (Hst 5), are small cationic proteins that are the major source of fungicidal activity of saliva. However, Hsts are rapidly degraded in vivo, limiting their usefulness as therapeutic agents despite their lack of toxicity. We constructed a conjugate peptide using spermidine (Spd) linked to the active fragment of Hst 5 (Hst 54–15), based upon our findings that C. albicans spermidine transporters are required for Hst 5 uptake and fungicidal activity. We found that Hst 54–15-Spd was significantly more effective in killing C. albicans and Candida glabrata than Hst 5 alone in both planktonic and biofilm growth and that Hst 54–15-Spd retained high activity in both serum and saliva. Hst 54–15-Spd was not bactericidal against streptococcal oral commensal bacteria and had no hemolytic activity. We tested the effectiveness of Hst 54–15-Spd in vivo by topical application to tongue surfaces of immunocompromised mice with OPC. Mice treated with Hst 54–15-Spd had significant clearance of candidal tongue lesions macroscopically, which was confirmed by a 3- to 5-log fold reduction of C. albicans colonies recovered from tongue tissues. Hst 54–15-Spd conjugates are a new class of peptide-based drugs with high selectivity for fungi and potential as topical therapeutic agents for oral candidiasis.

INTRODUCTION

Oral candidiasis is prevalent in individuals who have compromised or suppressed Th17 immunity (1) and is a common sequela of antibiotic therapies that reduce commensal bacteria in the mouth (2). Failures in treatment of candidemia and oral candidiasis are still encountered due to emergence of drug-resistant Candida species (3–5), thus emphasizing the need to develop alternate therapeutic agents.

Naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides are promising candidates for treatment of fungal infections because of their distinct mechanism of action from azole- and polyene-based antifungal drugs (6). Several proteins with antifungal activities are produced by human salivary glands and contribute to inhibition of growth and viability of Candida albicans within the oral environment (7). Among these, histatins are a family of histidine-rich cationic peptides secreted by human parotid and submandibular-sublingual salivary glands (8) with selective antifungal activity and little or no bactericidal activity (9). Among at least 50 histatin peptides derived from posttranslational proteolytic processing, histatin 5 (Hst 5), comprised of 24 amino acid residues, has the most potent fungicidal activity at physiological concentrations against C. albicans (10) and toward several medically important Candida species, such as Candida kefyr, Candida krusei, and Candida parapsilosis, as well as Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus (11–13). However, we found that many strains of Candida glabrata are significantly more resistant to Hst 5 due to their low uptake of Hst 5 (14).

Following their secretion, all Hsts undergo proteolytic degradation by native enzymes found in whole saliva as well as enzymes of bacterial origin (9), so that their functional activity is reduced and must be continuously replenished by new secretion (15). This unique mixture of enzymes present in whole saliva represents a challenge for preventing degradation of added antifungal peptides to be used therapeutically. Several approaches have been tried to synthesize Hsts that have increased fungicidal activity and resist degradation. Hst variants (Dhvar) were designed by replacement of multiple amino acids within Hst 5 (residues 11 to 24) to increase helical structure and hydrophobicity (16, 17). Several of these variants displayed increased fungicidal activity but also had broad-spectrum antimicrobial and hemolytic activities (16), thus diminishing their utility as antifungal agents for oral candidiasis. Alternatively, several synthetic congeners of Hst 5 were designed based upon small regions within the Hst 5 parent protein (18, 19). A 12-amino-acid subunit of full-length Hst 5, here named Hst 54–15 (AKRHHGYKRKFH), was as active as the full-length protein in its in vitro candidacidal activity (20). Hst 54–15 has some toxicity towards skin and respiratory pathogenic microorganisms, such as streptococci, staphylococci, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19, 21, 22); however, it is inactive against most oral commensal bacteria (9). This selectivity for fungi among members of the oral microbiome makes Hst 54–15 an attractive potential drug for oral candidiasis as it spares and preserves beneficial microbiota.

The fungicidal mechanism of Hst 5 in C. albicans is not a result of cytolysis or membrane disruption (23). Instead, we found that all cytotoxic events are initiated once Hst 5 reaches the cytosol, so that the ability of this protein to be transported intracellularly is essential for its fungicidal activity (23). We found that Hst 5 utilizes the polyamine transporters Dur3 and Dur31 for its uptake in C. albicans (Dur3 is the major uptake transporter, while Dur31 only functions under high concentrations of Hst 5) (24), since it is likely recognized as a polyamine-like substrate. Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine [Spd], and spermine) are small molecules that all carry a net positive charge (pKa values of 9 to 10), similar to Hst 5, and are essential for cell growth (25). Hst 5 is taken up by C. albicans Dur transporters along with essential polyamines, so that DUR expression levels are unlikely to be reduced in a manner leading to Hst 5 resistance (26). Heterologous expression of C. albicans DUR3 and DUR31 genes in C. glabrata increased cell sensitivity to Hst 5 in proportion to expressed levels of DUR transporters (14), underscoring the importance of polyamine transporters for Hst 5 toxicity. The critical role of polyamine transporters for Hst 5 uptake and toxicity suggested that the potency of this peptide might be increased by addition of a polyamine to either C or N termini in order to enhance its uptake by Dur transporters. The objective of this study was to construct a conjugate peptide having a polyamine added to the smaller active fragment of Hst 5 (Hst 54–15) and to examine its fungicidal activity. Among naturally occurring polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine), spermidine (Spd) was selected for conjugation because we found that Hst 5 uptake was most strongly blocked by Spd in competition assays, thus pointing to Spd as the closest Hst 5 substrate for Dur-mediated uptake (24). We chose to use the smaller active fragment of Hst 5 (Hst 54–15) for this work as it has slightly higher candidacidal activity than the full-length protein, and its smaller size facilitated chemical synthesis. Since we did not know which orientation of Spd with Hst 54–15 would be optimal, both N-terminal (Spd-Hst 54–15) and C-terminal (Hst 54–15-Spd) conjugates were synthesized. Here we report that Hst 54–15-spermidine (Hst 54–15-Spd) conjugates have significantly higher candidacidal activity both in vitro and in vivo than Hst 5 and that their rapid uptake and activity in biological fluids make them an attractive therapeutic drug.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and peptides.

All Candida strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Candida albicans CAF4-2 and Candida glabrata 931010, 90032, and 90030 were used as wild-type (WT) strains. C. albicans CAI4 was used for murine oral infections. Cells were maintained in Difco yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium with uridine added when required and stored at −78°C. Streptococcus gordonii DL1 was kindly provided by S. Ruhl (University at Buffalo). Streptococcus sanguinis SK36 and Streptococcus parasanguis FW213 were gifts from Hui Wu (University of Alabama). Spermidine was obtained from Sigma. Hst 54–15 peptides conjugated with spermidine (Spd-Hst 54–15 and Hst 54–15-Spd) were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (San Antonio, TX) using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry and N, N-di-cyclohexylcarbodiimide coupling reagent. Conjugates were designed with either a GGG linker region between peptide and spermidine (for Hst 54–15-Spd) or a succinic-GGG (HOCH2CH2CH2CO-GGG-) linker for Spd-Hst 54–15 in order to reduce potential steric effects between Spd and peptide. All peptide conjugates were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and their purity was confirmed by mass spectrometry. Peptide conjugates and their molecular weights and sequences are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Candida strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | |||

| CAF4-2 | CAF2-1 | Δura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 | 54 |

| CAI4 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 | 54 | |

| flu1Δ/Δ mutant | CAF4-2 | Δura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Δflu1::FRT | 26 |

| dur3Δ/Δ mutant | CAF4-2 | Δura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Δdur3::FRT | 24 |

| dur3/31Δ/Δ mutant | CAF4-2 | Δura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Δdur3::FRT/Δdur31::FRT | 24 |

| C. glabrata | |||

| 93101 | Wild type | 55 | |

| 90032 | Wild type | ATCC | |

| 90030 | Wild type | ATCC |

TABLE 2.

Sequences and characteristics of the peptides in this study

| Name | Mol wt | Sequence | Net charge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hst 5 | 3,035.8 | DSHAKRHHGYKRKFHEKHHSHRGY | +7 |

| Spd-Hst 54–15 | 1,978.3 | Spermidine-succinic-GGG-AKRHHGYKRKFH | +8 |

| Hst 54–15-Spd | 1,863.2 | AKRHHGYKRKFH-GGG-spermidine | +8 |

Candidacidal and bactericidal assays.

Candidacidal assays were performed using the microdilution plate method, as we have previously described (27). Of specific note, the activity of Hsts is quenched by the salts in RPMI 1640 medium, which is the test medium recommended to be used in CLSI and EUCAST reference microdilution assays for antifungal susceptibility testing. Therefore, a modified microdilution method outlined in reference 27 was used in this study. Briefly, single colonies of each strain were inoculated into 10 ml of YPD medium with uridine (50 μg/ml) and grown overnight at room temperature. Overnight-grown cells were diluted to an A600 of 0.3 to 0.4 and were incubated at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm until an A600 of ∼1.0 was attained. Cells were washed twice with 10 mM pH 7.4 sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), and then the cells (106) were mixed with different concentrations of different peptides (0, 7.5, 15, and 30 μM) at 30°C for 30 min and diluted in 10 mM NaPB, and aliquots of 500 cells were spread onto YPD agar plates and incubated for 36 to 48 h, until colonies could be visualized. Cell survival was expressed as a percentage compared with that of untreated control cells, and the percentage of killing was calculated as [1 − (no. of colonies from peptide-treated cells/no. of colonies from control cells)] × 100%. Assays were performed in triplicate for each strain. Candidacidal assays with germinated cells were performed as for yeast cells. To obtain germinated cells, overnight cultures were diluted to an A600 of 0.3 to 0.4 and incubated at 30°C with shaking until they reached an A600 of ∼0.7 to 0.8. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was added to sterilized YPD medium (9:1) to a final concentration of 10% FBS. Cells were incubated in YPD plus 10% FBS medium at 37°C with shaking for 1 h so that >90% of cells formed germ tubes that were not more than 2× the length of the mother cell in order to allow colony counting of single cells. Cells were washed twice with 10 mM pH 7.4 NaPB, and then 1 × 106 cells were mixed with serial dilutions of different peptides (0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 μM) at 30°C for 30 min. Surviving cells were calculated as described above. For candidacidal assays in the presence of saliva, assays were performed as described above, except whole saliva was added to phosphate buffer (1:1 by volume) with or without 1× proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini EDTA-free; Roche, Mannheim, GmbH).

The antimicrobial activity of peptides against S. gordonii, S. sanguinis, and S. parasanguinis was tested by the broth microdilution method using Todd-Hewett (TH) broth (Becton, Dickinson), based on the CLSI approved standard (28). Initial inoculums of 5 × 106 CFU/ml were incubated with and without Hst 5 and Hst 54–15-Spd in polystyrene 96-well plates (Becton, Dickinson) for 24 h at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm. The MIC was taken as the lowest concentration of each peptide that resulted in more than 99.9% reduction of growth. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Hst 54–15-Spd competition assays.

Competition assays were performed as described previously (24). Briefly, overnight-grown wild-type cells were prepared as for candidacidal assays. Cells (1 × 106) were suspended in 50 μl of NaPB, and then Hst 54–15-Spd (15, 30 and 60 μM) and fluorescently labeled spermidine (BODIPY-X-Spd; 100 μM) were added to the cells. Fluorescent counts were recorded at 30°C using a Bio-Tek multifunction plate reader and Gen5 software (provided by the University at Buffalo Confocal Microscopy and Flow Cytometry Core Facility). Cellular uptake of BODIPY-X-Spd resulted in a decrease in total fluorescence counts that was normalized with control wells, and uptake values were determined using a standard curve of fluorescence counts for known amounts (3.5 to 10 nmol) of BODIPY-X-Spd.

Biofilm formation with antifungal peptides.

Overnight-grown cells (C. albicans CAF4-2 and C. glabrata 90030) were diluted to an A600 of 0.3 to 0.4 and were incubated at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 4 h. Cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended to an A600 of ∼1 in NaPB (pH 7.4). One milliliter of cells was added to each well of a 12-well tissue culture plate (Becton, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h, and then nonadherent cells were removed by gently washing the wells with NaPB, 1 ml of fresh yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium was added, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After 24 h, all group samples were washed twice with 1 ml NaPB. For control groups, 1 ml of YNB was added to each well after washing, and then the plates were incubated at 37°C for another 36 h. For peptide-treated groups, 500 μl of antimicrobial peptide (Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd at a final concentration of 60 μM) was added to each well, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and then 500 μl of YNB medium was added to quench the activity of antifungal peptides and biofilms were incubated at 37°C for another 36 h. Initially, we performed XTT assays to assess biofilm mass, but found that this assay did not give colorimetric readings with Candida glabrata. Hence, biofilms from each sample were removed mechanically by scraping and collected into preweighed tubes, and dry weights of cells per well were calculated (29). Experiments were conducted in triplicate. The data represent mean cell dry weight with standard error. Differences between experimental groups were evaluated for significance by unpaired t test, using Prism 5.0 software.

Time-lapse confocal microscopy.

Overnight-grown C. albicans CAI4 cells were inoculated in fresh YPD media and grown to an optical density (OD) of 1.0. Coverglasses in chambered wells (Lab-Tek II) were precoated with concanavalin A (Sigma) (1 mg/ml solution in water), incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and washed twice with 10 mM NaPB. Cells (1 × 106) were deposited in the chamber, and 1 ml of 10 mM NaPB containing 5 μg/ml of propidium iodide (PI; Sigma) and Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd (60 μM) was added to the chamber. Confocal images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) using Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 objectives. Images were taken every 30 s. ImageJ software was used for image acquisition and total mean fluorescent intensity analysis.

Hemolysis assays.

Serial dilutions of 100 μl Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd (0, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 250 μM) were mixed with equal volumes of 4% murine red blood cell (RBC) suspensions (100 μl) in normal saline prepared from freshly collected blood (30). The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min. Aliquots (100 μl) of supernatant were transferred to 96-well plates. The effect of Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd on erythrocyte membranes was estimated by calculating the amount of hemoglobin released from disrupted erythrocytes, which was determined spectrophotometrically at A540. Zero lysis and 100% hemolysis were determined in Tris buffer (pH 8.10, 20 mM Tris, 0.1 M NaCl) and 0.05% Triton X-100, respectively. Percentage hemolysis was calculated as [(A540 in the peptide solution − A540 in Tris buffer)/(A540 in 0.05% Triton X-100 − A540 in Tris buffer] × 100%.

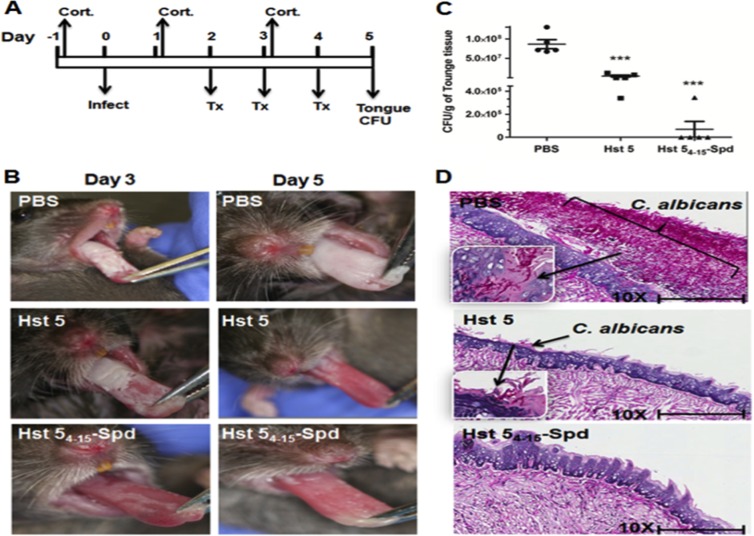

Efficacy of antifungal peptides in murine oral candidiasis.

Murine oral candidiasis infection was performed as previously described (26) using a protocol approved by the University of Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (project no. ORB06042Y) with slight modification (31, 32). All infections were performed under anesthesia using ketamine (10 mg/ml) and xylazine (1 mg/ml) to a final concentration of 110 mg/kg body weight, and all topical treatment procedures were performed under anesthesia using isoflurane gas. Every experimental replicate had a total of 15 C57BL/6J mice (6- to 8-week-old, female mice) (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), and the mice were grouped as untreated or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated controls (group 1; n = 5), Hst 5 treated (group 2; n = 5), and Hst 54–15-Spd treated (group 3; n = 5). Experiments were repeated independently at least three times. Immunosuppression was performed by subcutaneous injection of 225 mg/kg body weight cortisone 21-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich; C3130-5G) on day −1 prior to the infection and days +1 and + 3 after infection. All three groups of mice were infected with C. albicans strain CAI4 (URA+; 1 × 107 cells/ml) impregnated in a cotton swab for 2 h under the tongue. In the control group, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution was used as a treatment compound. Treatment was started on second day after infection (because mice start developing visible lesions around day 2) with 50 μl of 250 μM (781 μg/ml) Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd in respective groups. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane gas (XG-8 gas anesthesia System; Xenogen USA) for 2 min prior to topical treatment. Solutions consisting of 50 μl of PBS, Hst 5 (250 μM), or Hst 54–15-Spd (250 μM) were applied onto the anterior dorsum of the tongue for 60 s. Mice fully recovered within 5 min and were returned to cages without restrictions on eating or drinking. Topical treatment was repeated on days 3 and 4. After 5 days of infection, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia (ketamine-xylazine), and the tongue and adjacent hypoglossal tissues were excised and cut into halves laterally. One-half was weighed and homogenized for quantification of infection levels by CFU/g tongue tissue, and the other half was processed for histopathological analysis following fixation in zinc-buffered formalin followed by 70% ethanol and then embedded in paraffin. Thin sections were cut and stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain.

RESULTS

Candidacidal activity of Hst 54–15 conjugated with Spd.

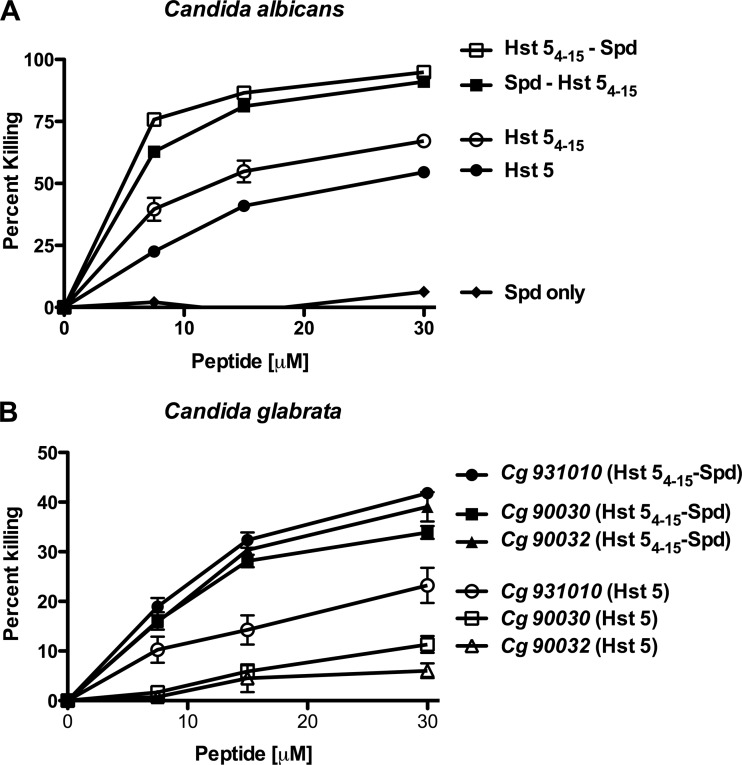

Susceptibility of C. albicans to both conjugates was tested, along with that to Hst 5 and Spd as controls (Fig. 1A). Spd alone had no toxicity toward cells at 7 to 15 μM and only 3 ± 0.4 to 10 ± 0.15% killing at 30 μM to 60 μM (data not shown). Both Hst-Spd conjugates showed at least twice the candidacidal activity at all concentrations of Hst 5 tested in C. albicans (Fig. 1A). Both conjugates had equivalent killing activity at higher concentrations; however, Hst 54–15-Spd had significantly (P < 0.05) higher candidacidal activity than Spd-Hst 54–15 at lower (7.5 μM) concentrations. Since the Hst 54–15-Spd conjugate had slightly better activity, we focused subsequent experiments on examination of this construct. Also, we assessed the bactericidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd against oral commensal bacteria (Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus parasanguinis) and found that its MIC was >781 μg/ml (>250 μM), thus showing the selectivity of this peptide conjugate for C. albicans.

FIG 1.

Hst 5 and Spd conjugates have higher candidacidal activities towards both C. albicans and C. glabrata. Susceptibility of C. albicans and C. glabrata was tested using candidacidal assays. (A) C. albicans cells (CAF4-2) were exposed to Spd, Hst 5, Hst 54–15, Spd-Hst 54–15, and Hst 54–15-Spd (7.5 to 31 μM), and the percentage of killing was calculated. Both Spd-Hst 54–15 and Hst 54–15-Spd showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher candidacidal activity in C. albicans than Hst 5. (B) For C. glabrata, three wild-type strains (Cg 931010, 90032, and 90030) were exposed to Hst 54–15-Spd and Hst 5. Candidacidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd against three strains of C. glabrata was increased by at least 2 times compared with Hst 5.

Candidacidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd against three strains of C. glabrata (931010, 90030, and 90032) was at least 2 times higher than that of Hst 5 (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, although there were significant differences among the three strains in sensitivity towards Hst 5 due to differences in Hst 5 uptake (14), all three C. glabrata strains were equally sensitive to Hst 54–15-Spd, suggesting that the conjugate was equally well transported by all strains.

Dur3 is the preferential uptake transporter for Hst 54–15-Spd in C. albicans.

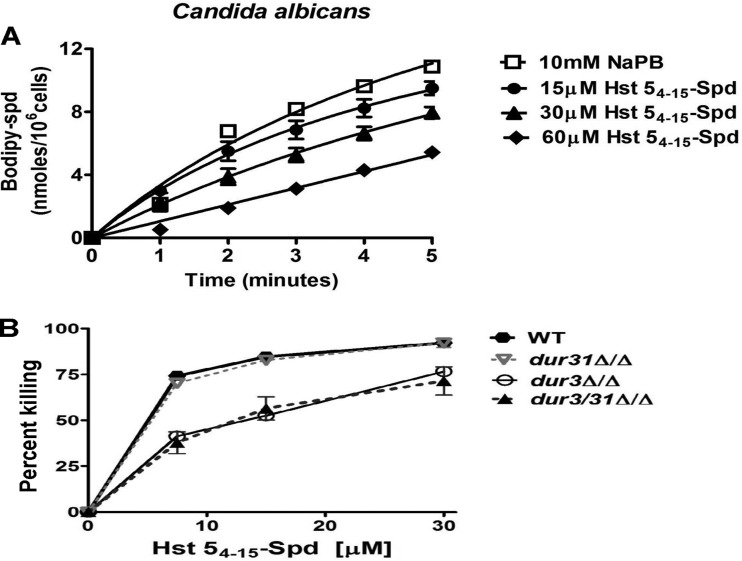

We previously found that Hst 5 competes for C. albicans intracellular uptake with Spd (24); so to confirm that Hst 54–15-Spd also utilizes Spd (Dur) transporters for its uptake, competition assays using BODIPY-X-Spd were performed. A dose-dependent reduction in Spd uptake in the presence of different concentrations (15, 30, and 60 μM) of Hst 54–15-Spd was found (Fig. 2A) that was similar to that of Hst 5 in our previous study, thus showing that the Hst 54–15-Spd conjugate utilizes the same transporters as Spd and Hst 5 for its entry into cells. Since C. albicans Dur3 and Dur31 polyamine transporters are involved in Hst 5 uptake (24), we expected similar use of these transporters for Hst 54–15-Spd translocation. C. albicans WT (CAF4-2), dur3Δ/Δ, dur31Δ/Δ, and dur3/31Δ/Δ strains were tested for sensitivity to Hst 54–15-Spd (Fig. 2B). (The relevant genotype for the designation “dur3/31Δ/Δ” is shown in Table 1.) As we previously found for Hst 5, deletion of DUR3 in C. albicans resulted in significant loss of Hst 54-15-Spd sensitivity (P < 0.05); however, there was no significant difference in sensitivity of dur31Δ/Δ cells. The dur3/31Δ/Δ double mutant was identical in its susceptibility to Hst 54-15-Spd to the dur3Δ/Δ strain, thus showing that Dur3 plays a primary role in Hst 54-15-Spd uptake.

FIG 2.

Hst 54–15-Spd competes for uptake with spermidine and uses Dur3 transporters in C. albicans. (A) Spermidine (Spd) uptake was calculated for 5 min after addition of BODIPY-X-Spd (100 μM). Hst 54–15-Spd showed significant (P < 0.01) competition for Spd uptake in C. albicans cells in a dose-dependent manner. (B) The C. albicans wild-type (CAF4-2) and Hst 5 uptake transporter-deficient (dur3Δ/Δ, dur31Δ/Δ, and dur3/31Δ/Δ) strains were exposed to Hst 54–15-Spd, and the percentage of killing was calculated. Both the dur3Δ/Δ and the double gene deletion dur3/31Δ/Δ strains were found to be significantly (P < 0.05) less sensitive to Hst 54–15-Spd.

Previously, we found C. albicans Flu1 is able to transport Hst 5 out of cells and thus reduce its toxicity (26). To determine whether Flu1 also plays a role in efflux of Hst 54–15-Spd, we tested antifungal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd in the C. albicans wild type and flu1Δ/Δ mutant strain. There was no significant difference in Hst 54–15-Spd toxicity between these two strains (data not shown), showing that Flu1 does not contribute to Hst 54–15-Spd export from the cells.

Hst 54–15-Spd inhibits growth of C. albicans and C. glabrata biofilms.

Biofilms formed by yeast cells often have reduced susceptibility to antifungal agents compared with planktonic cells; therefore, we examined the sensitivities of biofilms formed by C. albicans and C. glabrata to Hst 54–15-Spd and Hst 5 (Fig. 3). C. albicans biofilm mass was reduced by only 24% following incubation with Hst 5, while Hst 54–15-Spd reduced biofilm formation by 43%. In contrast, Hst 5 had no ability to reduce C. glabrata biofilm mass, while incubation with Hst 54–15-Spd significantly reduced C. glabrata biofilm production by 41%.

FIG 3.

C. albicans and C. glabrata biofilms were more sensitive to Hst 54–15-Spd than Hst 5. Biofilms were formed for 24 h in tissue culture plates, and then Hst 54–15-Spd or Hst 5 (60 μM) was added for 1 h, and the cells were grown further for 24 h. (A) Reduction of biofilm formation in C. albicans was detected in the presence of both Hst 54–15-Spd and Hst 5. (B) Significant (P < 0.005) reduction in C. glabrata biofilms was detected only in the presence of Hst 54–15-Spd (**, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0001).

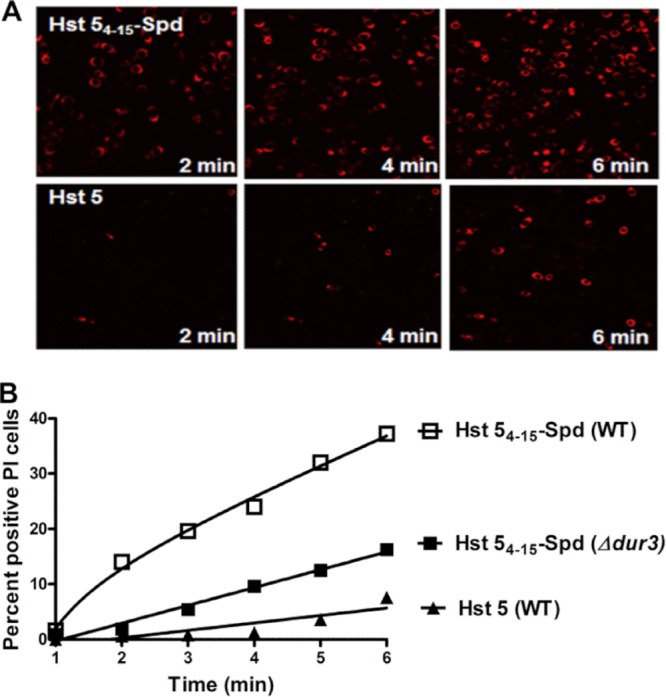

The translocation rate of Hst 54–15-Spd into C. albicans cells is higher than that of Hst 5.

Since we were unable to synthesize an N-terminally labeled Hst 54–15-Spd as we did for Hst 5, we could not measure uptake of Hst 54–15-Spd directly. As propidium iodide (PI) uptake is a direct functional consequence of ionic efflux and vacuole expansion induced only after uptake of Hst 5 (23), we used intracellular PI as an indirect measurement for Hst 54–15-Spd uptake visualized by time-lapse confocal microscopy. C. albicans cells treated with Hst 54–15-Spd showed rapid PI uptake within 5 min of treatment: 37% PI positive, compared with only 16% PI-positive cells treated with Hst 5 (Fig. 4A and B). Ninety percent of C. albicans cells were PI positive within 10 min of treatment with Hst 54–15-Spd. In contrast, only 50% of Hst 5 treated cells were PI positive within 15 min, while over 30 min was required to achieve 80% PI-positive Hst 5-treated cells (data not shown). C. albicans DUR3Δ/Δ knockouts had significantly fewer PI-positive cells when treated with Hst 54–15-Spd, supporting the role of these transporters in Hst 54–15-Spd uptake (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Hst 54–15-Spd is more rapidly internalized by C. albicans cells than Hst 5. (A) Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd was added to C. albicans cells in 10 mM NaPB buffer containing propidium iodide (PI) (5 μg/ml), and images were recorded every 10 s for 30 min using time-lapse confocal microscopy. Total PI-positive cells were measured in a cell population (500 cells) treated with Hst 5 (60 μM) or Hst 54–15-Spd (60 μM). (B) The percentage of PI-positive cells was calculated for each minute after addition of Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd to determine the rate of peptide uptake.

Hst 54–15-Spd is more stable than its parent peptide, Hst 5.

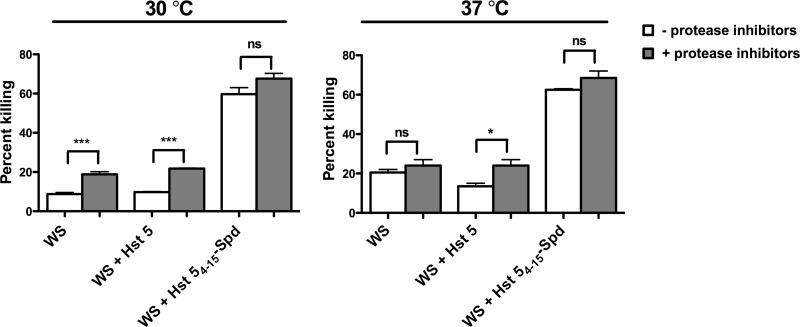

In order to determine the relative susceptibility of Hst 54–15-Spd to proteolytic degradation in whole saliva, we examined the candidacidal activity of peptides added to fresh whole human saliva with and without protease inhibitors. Since Hst 5 degradation in saliva is increased with physiological temperatures (33), we tested peptides at both 30°C and 37°C (Fig. 5), using whole saliva (WS) alone as a control. WS alone had low candidacidal activity that was increased by addition of protease inhibitors at 30°C. Addition of an equimolar concentration of spermidine (31 μM) to WS did not alter its fungicidal activity, irrespective of the presence or absence of protease inhibitors (data not shown). Hst 54–15-Spd (31 μM) added to whole saliva showed significantly (P < 0.001) higher (3-fold) candidacidal activity (67% ± 3.8% and 62% ± 0.7% killing at 30 and 37°C, respectively) than that of Hst 5 added to whole saliva (21% ± 0.84% and 13% ± 2.1% killing at 30 and 37°C, respectively). Hst 5 candidacidal activity significantly increased at both 30°C (P < 0.001) and 37°C (P < 0.05) in the presence of protease inhibitors. However, the high candidacidal activities of Hst 54–15-Spd in saliva were similar with or without protease inhibitors; showing the activity was protease independent. These results confirm that Hst 5 degradation and loss of candidacidal activity occur in whole saliva but remarkably showed that Hst 54–15-Spd is resistant to salivary proteases and retains high candidacidal activity in whole human saliva.

FIG 5.

Hst 54–15-Spd showed higher protease-independent candidacidal activity in human whole saliva than Hst 5. Whole saliva with or without added protease inhibitors was incubated with an equal volume (1:1) of fungal cell suspension in NaPB, in which Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd was added to a final peptide concentration of 31 μM. Hst 5 candidacidal activity was significantly increased at both 30°C (***, P < 0.001) and 37°C (*, P < 0.05) in the presence of protease inhibitors; however, Hst 54–15-Spd had significantly (P < 0.05) higher candidacidal activity than Hst 5 in saliva with or without protease inhibitor, showing its activity was protease independent.

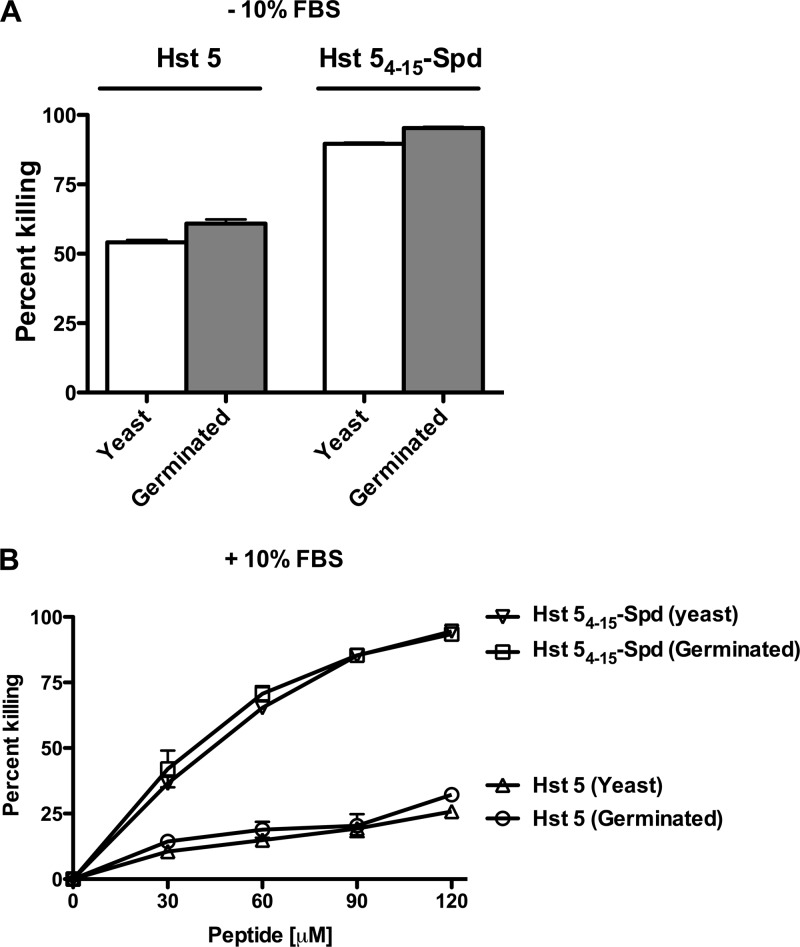

Next, we examined whether C. albicans germinated cells were equally susceptible to the fungicidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd as yeast cells. There was no significant difference in the sensitivity to Hst 54–15-Spd to germinated cells compared with yeast cells, although Hst 5 had slightly higher activity with germinated cells (P = 0.0167) compared to yeast cells (Fig. 6A). To determine if Hst 54–15-Spd retained fungicidal activity in serum, we tested the fungicidal activity of Hst 5 and Hst 54–15-Spd in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). As expected, Hst 5 had very low candidacidal activity in serum, killing ≈25% of either germinated or yeast cells even at very high (120 μM) concentrations. In contrast, Hst 54–15-Spd had significantly (P < 0.001) higher activity than Hst 5 in 10% FBS against both yeast cells and germinated cells (Fig. 6B). Although a 2-fold-higher concentration of Hst 54–15-Spd in 10% FBS was needed for comparable fungicidal activity in NaPB alone (Fig. 6A), its killing could be increased up to 90% with higher peptide concentrations—unlike Hst 5, which retained low killing activity even at high doses in the presence of 10% FBS. Thus, Hst 54–15-Spd exhibits significant fungicidal activity even in the presence of serum in the environment.

FIG 6.

Hst 54–15-Spd showed higher candidacidal activity in serum against C. albicans yeast and germinated cells. (A) C. albicans yeast or germinated cells (106 cells) were exposed to Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd without serum. Both Hst 5 and Hst 54–15-Spd 5 were equally active against germinated C. albicans cells compared to yeast cells, although the candidacidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd 5 was significantly greater (P < 0.001). (B) C. albicans yeast or germinated cells were incubated with serial dilutions of Hst 5 or Hst 54–15-Spd in the presence of 10% serum. Hst 54–15-Spd showed significantly (P < 0.001) higher candidacidal activity at all concentrations in serum compared to Hst 5.

Antifungal efficacy of Hst 54–15-Spd in a murine model of oral candidiasis.

Prior to in vivo experiments, the toxicity of these peptide conjugates was evaluated by using hemolysis assays. No hemolytic activity was detected at any concentration (1 to 250 μM) of conjugate examined (data not shown).

Next, we tested the efficacy of Hst 54–15-Spd as a topical application to an established infection in a murine model of oral candidiasis (34). Mice do not produce salivary histatins, so native secretions will not confound exogenous application of Hst 5. Before infection, we confirmed that mice were not carrying C. albicans cells in the oral cavity, as assessed by culturing oral swabs for each animal. BALB/c mice were immunosuppressed with cortisone, and oral infection with C. albicans was established prior to the first treatment with the PBS control, Hst 5, or Hst 54–15-Spd (250 μM in NaPB) (n = 5 per experimental group) (Fig. 7A). Extensive white lesions typical of oral candidiasis were found on the dorsal surfaces of tongues of mice in the control group by day 3 and became nearly confluent by day 5 (Fig. 7B). In contrast, mice treated with Hst 5 had reduced but still visible white lesions on day 3, while tongues of Hst 54–15-Spd-treated animals had negligible white lesions within the area of topical application. The clinical appearance of tongues was more striking at day 5 in that Hst 54–15-Spd-treated regions appeared pink and free of lesions, while Hst 5-treated tongues had light lesions, and underlying tissues appeared more reddened.

FIG 7.

Hst 54–15-Spd peptide is more effective in clearing murine oral candidiasis than Hst 5. (A) Timeline of oral candidiasis infection protocol shows immunosuppression with cortisone (Cort.), infection (infect) with C. albicans, and topical treatment times with peptides (Tx). (B) The clinical appearance of fungal lesions on animal tongues is shown on days 3 and 5 postinfection with C. albicans. (C) CFU per gram of tongue tissues were recovered from C. albicans-infected mice. Hst 54–15-Spd-treated mice (***, P < 0.001) and Hst 5-treated mice (**, P < 0.01) showed significantly reduced tongue CFU compared to PBS-treated animals. (D) Tongue tissues were stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain and viewed at ×10 magnification. The magnified inset shows typical hyphal invasion of the superficial epithelium. Hst 54–15-Spd-treated mouse tongue tissues did not have visible Candida cells and showed normal lingual papillae.

Tongues from PBS-treated mice contained 5 × 107 to 5 × 108 C. albicans cells per g of tongue tissue, whereas tongues from Hst 5-treated mice had about 2-log fold reductions in cells (≈106 C. albicans/g) (Fig. 7C). Topical treatment with Hst 54–15-Spd resulted in highly significant (P < 0.0001) reduction in C. albicans cells compared to the control group (average of 104 C. albicans cells/g), and several tongues had no recoverable C. albicans. This result was reproducible in additional independent experiments, and at even higher control infection levels (108 C. albicans cells/g), Hst 54–15-Spd topical treatment significantly reduced tongue tissue infection by 3- to 4-log fold (5 × 104 C. albicans cells/g) compared to a 2-log fold reduction with Hst 5 (4.3 × 106 C. albicans cells/g). Histological examination of tongues after sacrifice on day 5 substantiated the clinical appearance. Control group tongue tissue surfaces were heavily colonized by C. albicans, including invasive hyphae penetrating the mucosal epithelial layer. These tissues had extensive inflammatory cell infiltration, as well as gross damage to oral epithelia with loss of rete peg structures (Fig. 7D). Hst 5-treated mice showed comparatively less C. albicans surface colonization with little epithelial invasion and only partial loss of rete peg structures. Tongues of mice treated with Hst 54–15-Spd showed no evidence of infection in the areas treated topically and had completely normal rete peg structure and epithelial morphology. Thus, these experiments showed Hst 54–15-Spd was highly effective as a topical treatment for murine oral candidiasis compared to Hst 5.

DISCUSSION

Novel and selective candidacidal activity of Hst 54–15-Spd conjugates.

Instead of amino acid substitutions that enhance overall amphipathicity of the peptide and broaden its antimicrobial activity, our approach has been through rational selection of a carrier molecule to improve fungus-specific Hst 5 killing based upon our discovery that Hst 5 utilizes polyamine transporters for its uptake. Previously we found that Hst 5 uptake, rather than binding, is the key element limiting its fungicidal activity, since Hst 5 is not a lytic peptide but instead targets selective functional processes once it has reached the cytosol. This is the first report in which modification of a conjugate peptide based upon its mechanism of action in fungal cells has resulted in significantly improved and specific fungicidal activity. Previously, polyamines were used as vectors for delivery of anticancer drugs. For example, improved cytotoxicity towards cancer cell lines in vitro was found with artemisinin-spermidine conjugates due to enhanced polyamine transport and uptake (35). Interestingly, the same polyamine analogues and conjugates were found to be effective inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum due to their uptake through parasite polyamine transporters (35), thus pointing toward their use as antimalarial drugs. Recently, anthracene and benzene-polyamine conjugates were shown to be effective against Pneumocystis pneumonia, since these conjugates had higher affinities toward polyamine transporters and inhibited the uptake of native polyamines, thus reducing the severity of infection and lung inflammation (36).

These and other studies show that the structural requirements for uptake of polyamine conjugates are not stringent; thus, a wide variety of analogs may be transported by polyamine uptake systems, as illustrated by our findings demonstrating uptake of Hst 5 by C. albicans Dur3/31 polyamine transporters (24). Although it might be anticipated that spermidine conjugated to a 12-amino-acid cationic peptide might hinder its uptake, instead we found that the conjugate molecule had an accelerated rate of uptake by C. albicans cells. Hst 5 fungicidal activity is not dependent upon small changes in net charge or upon chirality (19); thus, it is possible that the Hst 54–15 peptide when conjugated to spermidine allows it to assume a more compact or globular conformation that is a more favorable substrate for fungal polyamine transporters. This is the likely the reason for the somewhat higher fungicidal activity of Spd when conjugated at the C terminus compared with the N terminus, as a result of differences in charge clustering due to a less-ordered secondary structure. However, the presence of spermidine plays a role in recognition of both Hst 54–15-Spd conjugates by Dur transporters to drive its uptake.

Commensal oral bacteria are important to the health of the mouth and prevention of overgrowth of C. albicans. For example, oral administration of the probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 to mice with oral candidiasis reduced the severity of candidiasis (37). Hst 5 itself has no microbicidal activity with commensal human oral bacteria, including Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis (16), and we found that the conjugate Hst 54–15-Spd was also inactive against S. gordonii, S. sanguinis, and S. parasanguinis. Although it is not known whether the lack of microbicidal activity against these streptococcal species is because Hst 5 is not taken up by cells or if bacteria lack intracellular targets, studies with Staphylococcus aureus showed that Hst 5 was not taken up by these bacteria (38). Prokaryotic cells express two types of polyamine transporters, namely, spermidine-preferential (PotABCD) and putrescine-specific (PotFGHI) ATP-binding cassette transporters, which differ substantially from yeast cells (39, 40). Such differences between yeast and bacterial polyamine transporters suggest that bacteria do not take up Hst 5 or its conjugate molecule. In either case, the specificity of Hst 54–15-Spd for fungal cell uptake makes it advantageous as a drug selective for treatment of oral candidiasis, so that even large dosages might not disturb the protective commensal microbiome in the oral cavity.

Modifications of Hst 5 primary structure have been investigated extensively in order to achieve a peptide with higher activity than the native Hst 5. Single or multiple amino acid substitutions were employed to increase both the lateral amphipathicity and helical conformation of the synthesized Hst peptide, in order to increase its propensity to associate with membranes (16). Using this strategy, multisite-substituted Hst 5 analogues (dhvar1 and dhvar2) were constructed and exhibited increased fungicidal activity over Hst 5 (16); however, both dhvar1 and dhvar2 analogues showed increased membranolytic and hemolytic activities (41, 42) and inhibited the growth of the oral commensal bacterium Streptococcus sanguis (16). Unexpectedly, dhvar2 was found to increase HIV-1 replication by promoting the envelope-mediated cell entry process, likely as a result of its membrane activity (43). Thus, although these Hst 5 modifications improved fungicidal activity, they also resulted in broader-spectrum antibacterial and hemolytic activities as well as enhanced HIV-1 replication, so that their clinical utility is limited. In contrast, the Hst 54–15-Spd conjugate has none of the drawbacks associated with nonspecific membranolytic activity.

Stability of Hst 54–15-Spd conjugates in saliva and serum.

A major disadvantage to using Hst 5 in treatment of oral candidiasis is that its antifungal activity is rapidly lost in saliva due to proteolytic degradation by salivary enzymes (15) and by secreted C. albicans proteolytic enzymes (44). Among the family of antifungal Hst proteins, Hst 5 is the most fungicidal, but it is also the most susceptible to proteolytic activity in whole saliva (45, 46). Thus, topical treatment of ex vivo murine tongue tissues with Hst 5 was no more effective than treatment with saliva alone in preventing C. albicans colonization of tissues (47). To overcome this problem, another approach has been to stabilize its structure through introduction of a single disulfide bond (48) or by N- to C-terminal cyclization (49). Cyclization of Hst 1 increased its activity by 1,000-fold (49), while cyclization of Hst 3 using disulfide bonds or a lactam bridge increased its killing of yeast by 100-fold without an increase in hemolysis (47). Importantly, these modifications induced a more compact folded structure that increased the Hst half-life in serum (47), presumably by masking proteolytic cleavage sites. Similarly, we found that Hst 54–15-Spd was less sensitive to protease degradation in saliva, suggesting that this conjugate has a more compact or folded structure with fewer exposed protease substrate sites. Furthermore, our results from topical application in vivo point to an enhanced half-life at the site of application, since only three doses were needed to treat the infection.

Topical antifungal therapy is the recommended first line of treatment for uncomplicated oral candidiasis or denture stomatitis (50). The advantages of topical therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) are direct drug exposure at the oral mucosa site of infection as well as the lack of adverse systemic effects or drug interactions (51). Although azole antifungals are commonly used as topical (and systemic) therapeutics for oral candidiasis, their use is contraindicated in patients with recurrent oral yeast infections due to a risk of selection and enrichment of drug-resistant strains (52). As an alternative to azole therapeutics, we report that topical treatment with Hst 54–15-Spd was highly effective at doses well below those of systemic fluconazole (53), as tongues of treated animals had negligible white lesions within the area of topical application. Similar to native Hst 5, spermidine conjugates of the active fragment of Hst 5 are nontoxic and have a higher clinical half-life, enhanced uptake into Candida cells, and greater candidacidal efficacies than Hst 5. Although further studies regarding potential toxicity of these conjugate peptides in humans need to be done, this study highlights the potential of histatins conjugated with polyamines as potent anticandidal drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant R01DE010641 (ME) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

We thank Wade J. Sigurdson, Director, Confocal Microscopy Facility, University at Buffalo, for assistance with microscopy and FACScan, and Moon-Il Cho, University at Buffalo, for helpful discussions regarding analyses of oral histology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 November 2013

S.T. and R.L. are co-first authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conti HR, Baker O, Freeman AF, Jang WS, Holland SM, Li RA, Edgerton M, Gaffen SL. 2011. New mechanism of oral immunity to mucosal candidiasis in hyper-IgE syndrome. Mucosal Immunol. 4:448–455. 10.1038/mi.2011.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanaguchi N, Narisawa N, Ito T, Kinoshita Y, Kusumoto Y, Shinozuka O, Senpuku H. 2012. Effects of salivary protein flow and indigenous microorganisms on initial colonization of Candida albicans in an in vivo model. BMC Oral Health 12:36. 10.1186/1472-6831-12-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, Vande Berg J, Hu J, Messer S, Herwaldt L, Pfaller M, Diekema D. 2003. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1172–1177. 10.1086/378745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan J, Meltzer MI, Plikaytis BD, Sofair AN, Huie-White S, Wilcox S, Harrison LH, Seaberg EC, Hajjeh RA, Teutsch SM. 2005. Excess mortality, hospital stay, and cost due to candidemia: a case-control study using data from population-based candidemia surveillance. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 26:540–547. 10.1086/502581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappas PG, Rex JH, Lee J, Hamill RJ, Larsen RA, Powderly W, Kauffman CA, Hyslop N, Mangino JE, Chapman S, Horowitz HW, Edwards JE, Dismukes WE; Mycoses Study Group NIAID 2003. A prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy, and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and pediatric patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:634–643. 10.1086/376906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupetti A, Danesi R, van 't Wout JW, van Dissel JT, Senesi S, Nibbering PH. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides: therapeutic potential for the treatment of Candida infections. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11:309–318. 10.1517/13543784.11.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamperini CA, Schiavinato PC, Pavarina AC, Giampaolo ET, Vergani CE, Machado AL. 17 December 2012. Effect of human whole saliva on the in vitro adhesion of Candida albicans to a denture base acrylic resin: a focus on collection and preparation of saliva samples. J. Invest. Clin. Dent. 10.1111/jicd.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oppenheim FG, Xu T, McMillian FM, Levitz SM, Diamond RD, Offner GD, Troxler RF. 1988. Histatins, a novel family of histidine-rich proteins in human parotid secretion. Isolation, characterization, primary structure, and fungistatic effects on Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 263:7472–7477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groenink J, Ruissen AL, Lowies D, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 2003. Degradation of antimicrobial histatin-variant peptides in Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus mutans. J. Dent. Res. 82:753–757. 10.1177/154405910308200918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu T, Levitz SM, Diamond RD, Oppenheim FG. 1991. Anticandidal activity of major human salivary histatins. Infect. Immun. 59:2549–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai H, Bobek LA. 1997. Human salivary histatin-5 exerts potent fungicidal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1336:367–369. 10.1016/S0304-4165(97)00076-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmerhorst EJ, Reijnders IM, van 't Hof W, Simoons-Smit I, Veerman EC, Amerongen AV. 1999. Amphotericin B- and fluconazole-resistant Candida spp., Aspergillus fumigatus, and other newly emerging pathogenic fungi are susceptible to basic antifungal peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:702–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartie KL, Devine DA, Wilson MJ, Lewis MAO. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group to antimicrobial peptides. Int. Endod. J. 41:586–592. 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tati S, Jang W, Li R, Kumar R, Puri S, Edgerton M. 2013. Histatin 5 resistance of Candida glabrata can be reversed by insertion of Candida albicans polyamine transporter-encoding genes DUR3 and DUR31. PLoS One 8:e61480. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmerhorst EJ, Alagl AS, Siqueira WL, Oppenheim FG. 2006. Oral fluid proteolytic effects on histatin 5 structure and function. Arch. Oral Biol. 51:1061–1070. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmerhorst EJ, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Simoons-Smit I, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 1997. Synthetic histatin analogues with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Biochem. J. 15:39–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenink J, Walgreen-Weterings E, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 1999. Cationic amphipathic peptides, derived from bovine and human lactoferrins, with antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:217–222. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Kamysz W, D'Amato G, Silvestri C, Del Prete MS, Licci A, Riva A, Lukasiak J, Scalise G. 2005. In vitro activity of the histatin derivative P-113 against multidrug-resistant pathogens responsible for pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1249–1252. 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1249-1252.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothstein DM, Spacciapoli P, Tran LT, Xu T, Roberts FD, Dalla Serra M, Buxton DK, Oppenheim FG, Friden P. 2001. Anticandidal activity is retained in P-113, a 12-amino-acid fragment of histatin 5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1367–1373. 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1367-1373.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei GX, Bobek LA. 2005. Human salivary mucin MUC7 12-mer-L and 12-mer-D peptides: antifungal activity in saliva, enhancement of activity with protease inhibitor cocktail or EDTA, and cytotoxicity to human cells Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2336–2342. 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2336-2342.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sajjan US, Tran LT, Sole N, Rovaldi C, Akiyama A, Friden PM, Forstner JF, Rothstein DM. 2001. P-113D, an antimicrobial peptide active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, retains activity in the presence of sputum from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3437–3444. 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3437-3444.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugiyama K. 1993. Anti-lipopolysaccharide activity of histatins, peptides from human saliva. Experientia 49:1095–1097. 10.1007/BF01929920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang WS, Bajwa JS, Sun JN, Edgerton M. 2010. Salivary histatin 5 internalization by translocation, but not endocytosis, is required for fungicidal activity in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 77:354–370. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07210.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R, Chadha S, Saraswat D, Bajwa JS, Li RA, Conti HR, Edgerton M. 2011. Histatin 5 uptake by Candida albicans utilizes polyamine transporters Dur3 and Dur31 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286:43748–43758. 10.1074/jbc.M111.311175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. 2006. Polyamine modulon in Escherichia coli: genes involved in the stimulation of cell growth by polyamines. J. Biochem. 139:11–16. 10.1093/jb/mvj020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, Kumar R, Tati S, Puri S, Edgerton M. 2013. Candida albicans Flu1-mediated efflux of salivary histatin 5 reduces its cytosolic concentration and fungicidal activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1832–1839. 10.1128/AAC.02295-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li XWS, Reddy MS, Baev D, Edgerton M. 2003. Candida albicans Ssa1/2p is the cell envelope binding protein for human salivary histatin 5. J. Biol. Chem. 278:28553–28561. 10.1074/jbc.M300680200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 9th ed. Approved standard M07-A9. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE, Sorrells TR, Mitrovich QM, Hernday AD, Tuch BB, Andes DR, Johnson AD. 2012. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148:126–138. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berne S, Krizaj I, Pohleven F, Tuck T, Macek P, Sepcić K. 2002. Pleurotus and Agrocybe hemolysins, new proteins hypothetically improved in fungal fruiting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1570:153–159. 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00190-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park H, Myers CL, Sheppard DC, Phan QT, Sanchez AA, Edwards EJ, Filler SG. 2005. Role of the fungal Ras-protein kinase A pathway in governing epithelial cell interactions during oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell. Microbiol. 7:499–510. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solis NV, Filler SG. 2012. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat. Protoc. 7:637–642. 10.1038/nprot.2012.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomadaki K, Helmerhorst EJ, Tian N, Sun X, Siqueira WL, Walt DR, Oppenheim FG. 2011. Whole-saliva proteolysis and its impact on salivary diagnostics. J. Dent. Res. 90:1325–1330. 10.1177/0022034511420721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun JN, Solis NV, Phan QT, Bajwa JS, Kashleva H, Thompson A, Liu Y, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Edgerton M, Filler SG. 2010. Host cell invasion and virulence mediated by Candida albicans Ssa1. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001181. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chadwick J, Jones M, Mercer AE, Stocks PA, Ward SA, Park BK, O'Neill PM. 2010. Design, synthesis and antimalarial/anticancer evaluation of spermidine linked artemisinin conjugates designed to exploit polyamine transporters in Plasmodium falciparum and HL-60 cancer cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18:2586–2597. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao C-P, Phanstiel O, Lasbury ME, Zhang C, Shao S, Durant PJ, Cheng BH, Lee CH. 2009. Polyamine transport as a target for treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5259–5264. 10.1128/AAC.00662-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishijima SA, Hayama K, Burton JP, Reid G, Okada M, Matsushita Y, Abe S. 2012. Effect of Streptococcus salivarius K12 on the in vitro growth of Candida albicans and its protective effect in an oral candidiasis model. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:2190–2199. 10.1128/AEM.07055-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welling MM, Brouwer CP, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 2007. Histatin-derived monomeric and dimeric synthetic peptides show strong bactericidal activity towards multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3416–3419. 10.1128/AAC.00196-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. 2010. Characteristics of cellular polyamine transport in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48:506–512. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higashi K, Sakamaki Y, Herai E, Demizu R, Uemura T, Saroj SD, Zenda R, Terui Y, Nishimura K, Toida T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. 2010. Identification and functions of amino acid residues in PotB and PotC involved in spermidine uptake activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285:39061–39069. 10.1074/jbc.M110.186536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruissen AL, Groenink J, Helmerhorst EJ, Walgreen-Weterings E, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 2001. Effects of histatin 5 and derived peptides on Candida albicans. Biochem. J. 356:361–368. 10.1042/0264-6021:3560361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Den Hertog AL, Wong Fong Sang HW, Kraayenhof R, Bolscher JG, van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. 2004. Interactions of histatin 5 and histatin 5-derived peptides with liposome membranes: surface effects, translocation and permeabilization. Biochem. J. 379:665–672. 10.1042/BJ20031785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groot F, Sanders RW, ter Brake O, Nazmi K, Veerman EC, Bolscher JG, Berkhout B. 2006. Histatin 5-derived peptide with improved fungicidal properties enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by promoting viral entry. J. Virol. 80:9236–9243. 10.1128/JVI.00796-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meiller TF, Hube B, Schild L, Shirtliff ME, Scheper MA, Winkler R, Ton A, Jabra-Rizk MA. 2009. A novel immune evasion strategy of Candida albicans: proteolytic cleavage of a salivary antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One 4:e5039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun X, Salih E, Oppenheim FG, Helmerhorst EJ. 2009. Kinetics of histatin proteolysis in whole saliva and the effect on bioactive domains with metal-binding, antifungal, and wound-healing properties. FASEB J. 23:2691–2701. 10.1096/fj.09-131045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campese M, Sun X, Bosch JA, Oppenheim FG, Helmerhorst EJ. 2009. Concentration and fate of histatins and acidic proline-rich proteins in the oral environment. Arch. Oral Biol. 54:345–353. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters BM, Zhu J, Fidel PL, Jr, Scheper MA, Hackett W, El Shaye S, Jabra-Rizk MA. 2010. Protection of the oral mucosa by salivary histatin-5 against Candida albicans in an ex vivo murine model of oral infection. FEMS Yeast Res. 10:597–604. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00632.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewer D, Lajoie G. 2002. Structure-based design of potent histatin analogues. Biochemistry 41:5526–5536. 10.1021/bi015926d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oudhoff MJ, Kroeze KL, Nazmi K, van den Keijbus PA, van 't Hof W, Fernandez-Borja M, Hordijk PL, Gibbs S, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC. 2009. Structure-activity analysis of histatin, a potent wound healing peptide from human saliva: cyclization of histatin potentiates molar activity 1,000-fold. FASEB J. 23:3928–3935. 10.1096/fj.09-137588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulak Y, Arikan A, Delibalta N. 1994. Comparison of three different treatment methods for generalized denture stomatitis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 72:283–288. 10.1016/0022-3913(94)90341-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laudenbach JM, Epstein JB. 2009. Treatment strategies for oropharyngeal candidiasis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10:1413–1421. 10.1517/14656560902952854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rautemaa R, Ramage G. 2011. Oral candidosis—clinical challenges of a biofilm disease. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 37:328–336. 10.3109/1040841X.2011.585606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hata K, Horii T, Miyazaki M, Watanabe NA, Okubo M, Sonoda J, Nakamoto K, Tanaka K, Shirotori S, Murai N, Inoue S, Matsukura M, Abe S, Yoshimatsu K, Asada M. 2011. Efficacy of oral E1210, a new broad-spectrum antifungal with a novel mechanism of action, in murine models of candidiasis, aspergillosis, and fusariosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4543–4551. 10.1128/AAC.00366-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joly S, Maze C, McCray PB, Jr, Guthmiller JM. 2004. Human beta-defensins 2 and 3 demonstrate strain-selective activity against oral microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1024–1029. 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1024-1029.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]