Abstract

Malaria remains a significant infectious disease that causes millions of clinical cases and >800,000 deaths per year. The Malaria Box is a collection of 400 commercially available chemical entities that have antimalarial activity. The collection contains 200 drug-like compounds, based on their oral absorption and the presence of known toxicophores, and 200 probe-like compounds, which are intended to represent a broad structural diversity. These compounds have confirmed activities against the asexual intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum and low cytotoxicities, but their mechanisms of action and their activities in other stages of the parasite's life cycle remain to be determined. The apicoplast is considered to be a promising source of malaria-specific targets, and its main function during intraerythrocytic stages is to provide the isoprenoid precursor isopentenyl diphosphate, which can be used for phenotype-based screens to identify compounds targeting this organelle. We screened 400 compounds from the Malaria Box using apicoplast-targeting phenotypic assays to identify their potential mechanisms of action. We identified one compound that specifically targeted the apicoplast. Further analyses indicated that the molecular target of this compound may differ from those of the current antiapicoplast drugs, such as fosmidomycin. Moreover, in our efforts to elucidate the mechanisms of action of compounds from the Malaria Box, we evaluated their activities against other stages of the life cycle of the parasite. Gametocytes are the transmission stage of the malaria parasite and are recognized as a priority target in efforts to eradicate malaria. We identified 12 compounds that were active against gametocytes with 50% inhibitory concentration values of <1 μM.

INTRODUCTION

More than 40% of the world's population is at risk of contracting malaria, and the continued emergence of drug resistance is a constant threat. As a result, the identification and characterization of new leads for the development of antimalarial drugs with different mechanisms of action are of the highest priority. Historically, antimalarial drug discovery and development have focused on the asexual intraerythrocytic stages of the life cycle of the parasite since these stages are responsible for the pathology. Gametocytes are the sexual stage of the malaria parasite and are essential for the transmission of the parasite to the mosquito. Most current antimalarials have little or no effect on gametocytes; thus, treated patients can still transmit malaria. The development of new drugs that have a broader spectrum of activity, including activity against gametocytes, is recognized as a highly favorable quality in the effort to eradicate malaria (1).

In order to catalyze the development of new antimalarials, the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and Scynexis, Inc., assembled the Malaria Box (2), an open-access library composed of 400 compounds originally identified by phenotypic screening of >4,000,000 compounds from the research libraries of Saint Jude Children's Research Hospital, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline (3). The in vitro antimalarial activities of the Malaria Box compounds span a range of 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values from 30 nM to 4 μM (2). The 400 compounds in the Malaria Box were selected based on several factors, including low toxicity, oral bioavailability, and chemical diversity; however, the primary selection was based on their commercial availability to ensure accessibility for follow-up experiments (2). Substantial information about these compounds is available at the ChEMBL-NTD archive (see https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chemblntd); this knowledge base is expected to grow iteratively as more research is performed. The Malaria Box compounds were selected based on global phenotypic screening against asexual intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum; however, their mechanisms of action and their efficacies against gametocyte stages remain unknown.

Malaria parasites contain a vestigial plastid called the apicoplast, which performs vital functions such as biosynthesizing isoprenoid precursors, fatty acids, and heme (4, 5). Plasmodium parasites utilize the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway to synthesize isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), which is essential for parasite growth (6, 7). This pathway is absent in humans, who rely on the mevalonate pathway instead. Recently, it was suggested that the MEP pathway and the biosynthesis of the isoprenoid precursors IPP and DMAPP represent the sole essential function of this organelle during asexual intraerythrocytic development of the parasites (8). The strongest support for this stems from the observation that loss of the apicoplast can be chemically complemented by supplementing the growth medium with IPP. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of drugs that directly target the biosynthesis of isoprenoid precursors or indirectly disrupt their biosynthesis by interfering with processes essential for apicoplast biogenesis, such as apicoplast DNA replication, transcription, and protein translation, may be reverted by IPP supplementation (8). As a result, the reversal of growth inhibition by IPP supplementation can be used as a phenotypic screening diagnostic to identify compounds within the Malaria Box that target the apicoplast, thus identifying their mechanisms of action and narrowing their potential molecular targets (8).

Several antibiotics, such as doxycycline (DOX), azithromycin, solithromycin, chloramphenicol, and clindamycin, kill malaria parasites by interfering with apicoplast genome replication, transcription, protein translation, posttranslation modification, or protein turnover (9–14). Parasites treated with these antibiotics initially present normal morphology and continue to grow and release daughter cells (merozoites) that are capable of invading new host cells. However, these progeny will not complete the following intraerythrocytic cycle since the apicoplast will fail to replicate and segregate; this phenomenon is known as the delayed-death phenotype (15). In contrast to those antibiotics, fosmidomycin (FOS) is an inhibitor that directly targets the metabolism of the apicoplast (7, 16–18). FOS shows a rapid onset of action, with IC50s between 300 and 1,200 nM for P. falciparum in vitro culture, depending on the strain (17, 18). FOS is a specific inhibitor of the second enzyme in the MEP pathway, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR), which is essential for the survival of P. falciparum (6, 17, 18). Therefore, a reversal of growth inhibition can aid in the characterization of the mechanisms of action to, ultimately, identify the molecular targets among the Malaria Box compounds.

In the present work, we aimed to identify the mechanisms of action of the compounds of the Malaria Box. By using cell-based phenotypic assays, we identified one drug-like compound that targets the apicoplast. Further analyses revealed that the mechanism of action of this compound is more similar to that of FOS than to that of DOX. In addition, we probed the Malaria Box for compounds that have activity against late-stage gametocytes, which is the stage that is most insensitive to the current antimalarials (19, 20). We identified 12 gametocytocidal compounds with IC50s of <1 μM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

The following P. falciparum strains were obtained through the MR4 Malaria Reagent Repository (ATCC, Manassas, VA) as part of the BEI Resources Repository (NIAID, NIH): D10-ACPL(leader)-GFP, MRA-568, deposited by A. F. Cowman; NF54, MRA-1000, deposited by M. Dowler, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research; and Dd2, MRA-150, deposited by D. Walliker. NF54 is sensitive to chloroquine. Dd2 is a pyrimethamine-, chloroquine-, and mefloquine-resistant strain. D10-ACPL-GFP has been transfected with a plasmid containing the leader sequence of the acyl carrier protein (ACP), which is targeted to the apicoplast and fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP), allowing observation of apicoplast development during the intraerythrocytic cycle of the parasite. The D10-ACPL-GFP plasmid is maintained by 0.1 μM pyrimethamine treatment (21). P. falciparum resistant to FOS was a generous gift from David Fidock (22) and was maintained by 1 μM FOS treatment.

Malaria Box.

The Malaria Box compound collection was provided by Scynexis, Inc. (Research Triangle Park, NC), for the MMV and supplied at 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Additional amounts of MMV008138 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and the results were reproduced using this commercial source.

P. falciparum cultures and drug sensitivities at asexual stages.

Parasites were maintained in O-positive human erythrocytes (4% hematocrit) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5 g/liter Albumax I (Gibco Life Technologies), 2 g/liter glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.3 g/liter sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich), 370 μM hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 mM HEPES, and 20 mg/liter gentamicin (Gibco Life Technologies). The parasites were kept at 37°C under reduced-oxygen conditions (5.06% CO2, 4.99% O2, and 89.95% N2).

The effect of each compound identified as gametocytocidal was further evaluated against asexual parasites from P. falciparum strains NF54 and Dd2 using the SYBR green assay as described previously (23, 24). Ten-point dilutions were used to test the dose responses at concentrations ranging from 5 μM to 0.002 μM. The IC50 calculation was performed with GraFit 5 (Erithacus Software Ltd.) using nonlinear regression curve fitting and represents the average of two independent experiments and the standard deviation (SD). We determined the IC50s for MMV008138, FOS, and DOX at 72 h and 96 h by a SYBR green assay to assess for the delayed-death phenotype. MMV008138 was also tested against FOS-resistant (FOSr) parasites by the SYBR green assay.

Reversal of growth inhibition by isopentenyl diphosphate supplementation.

Recently, it was demonstrated that parasites can survive in vitro without the apicoplast when IPP is supplied at 200 μM. A reversal of growth inhibition by IPP supplementation was proposed as a method for potentially identifying compounds that target apicoplast function (8). We assessed whether compounds from the Malaria Box were targeting the apicoplast by measuring their growth recoveries in the presence of inhibitor and IPP as described previously (8). Briefly, Dd2 strain ring stages were cultured under the following conditions: control (no drug), 5 μM Malaria Box compounds, and 5 μM Malaria Box compounds with 200 μM IPP, which is the necessary concentration to achieve 100% growth recovery (8). FOS was used as a control drug for growth inhibition and the reversal of growth inhibition by IPP. All conditions were set in 96-well plates (200 μl/well with 1% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia), incubated for 72 h, and analyzed by a SYBR green assay as described previously (23, 24). The percentage of growth was normalized to that of untreated control parasites. Since several compounds within the Malaria Box did not inhibit growth completely at 5 μM, we considered reversal of growth inhibition only when a compound alone exhibited >95% growth inhibition and >60% growth recovery in the presence of inhibitor and IPP. Uninfected erythrocytes were used for background determinations. Two independent experiments were performed.

To establish dose dependency for the reversal of growth inhibition, ring-stage parasite cultures (200 μl/well, 1% hematocrit, and 1% parasitemia) were grown for 72 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of the inhibitor and in the presence or absence of 200 μM IPP. The growth of the parasite was assessed by a SYBR green assay as described previously (23, 24).

Activity of MMV008138 against Toxoplasma gondii.

The T. gondii RH-HX-KO-YFP2-DHFR(m2m3) strain tachyzoites were maintained in human fibroblasts, and parasite growth was measured by a fluorescence assay as described previously (25). Drug assays were performed by 2-fold serial dilutions of MMV008138 dissolved in 100% DMSO using concentrations ranging from 5 μM to 0.039 μM. DMSO was added to a final concentration of 0.05% for all doses. Six replicates were used for each dose and control.

Gametocytocidal activity assay.

Malaria parasites do not replicate their genome during gametocytogenesis; however, they are metabolically active, especially their mitochondria (26). Therefore, gametocyte viability was measured using alamarBlue, a fluorescent oxidoreduction indicator, as a general measure of metabolic activity. In this assay, the fluorometric readings are proportional to the numbers of living gametocytes and correspond to their metabolic activities. Damaged and nonviable gametocytes have lower metabolic activities and, therefore, generate proportionally lower signals (dose dependent) than healthy gametocytes. We investigated whether the compounds from the Malaria Box were active in killing late-stage (stage V) gametocytes using the alamarBlue viability assay described previously by Tanaka and Williamson (27). Gametocytes were developed from the P. falciparum NF54 strain (a chloroquine-sensitive strain). Asexual stages were synchronized by sorbitol treatment 2 days before gametocyte cultures were started. P. falciparum subcultures for the generation of gametocytes were set at 1% parasitemia and 4% hematocrit, and the culture medium was not changed until day four after the subculture. Parasite development was evaluated by Giemsa-stained thin blood smears on days 4, 8, 12, and 13 after the initial subculture. Starting on day nine of gametocyte culture, the parasites were treated for 4 consecutive days with 5% sorbitol for 10 min at 37°C to remove the asexual parasites. Sorbitol treatment effectively removed >99% of the asexual parasites. Gametocyte recovery and concentration were achieved on day 13 using a NycoPrep 1.077 cushion, and the gametocytes were counted using a Neubauer chamber. About 30,000 to 50,000 gametocytes per well (100 μl final volume) were added to black flat-bottom half-area 96-well plates containing the drug candidates, 60 nM epoxomicin (28) (positive control), or DMSO (negative control). The plate was incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C and under low-oxygen conditions (5.06% CO2, 4.99% O2, and 89.95% N2) for 72 h. alamarBlue was added on day 16 postinduction at 10% of the well volume, and the plates were returned to the chamber for an additional 24 h. Fluorescence was determined at 585 nm after excitation at 540 nm. The initial screen was performed at 5 μM (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Compounds exhibiting >85% inhibition of metabolic activity compared to that of control were selected for further dose-dependent analyses using 10 μM as the highest concentration (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The IC50 calculation was determined from dose-response curves calculated from normalized percent activity values and log10-transformed concentrations using GraFit 5 software. Only compounds that showed a sigmoidal response were selected to report their gametocytocidal activity (see Table 2; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The final figures were prepared using GraphPad Prism 6 software (see Fig. S3).

TABLE 2.

In vitro antimalarial activity (IC50) against gametocytes (NF54 strain) and parasites at asexual stages (NF54 and Dd2 strains)

| MMV no. | Set | IC50 (nM) (mean ± SD) against: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gametocytesa in strain NF54 | Parasites in asexual stagesb in strain: |

|||

| NF54 | Dd2 | |||

| MMV000248 | Drug-like | 310 ± 50 | 50 ± 6 | 90 ± 10 |

| MMV019918 | Drug-like | 320 ± 60 | 280 ± 80 | 620 ± 280 |

| MMV006172 | Probe-like | 420 ± 30 | 40 ± 3 | 60 ± 3 |

| MMV019555 | Probe-like | 470 ± 60 | 20 ± 1 | 70 ± 5 |

| MMV666125 | Probe-like | 480 ± 120 | 120 ± 20 | 50 ± 2 |

| MMV019266 | Drug-like | 520 ± 30 | 310 ± 50 | 380 ± 20 |

| MMV665943 | Probe-like | 570 ± 80 | 190 ± 30 | 190 ± 20 |

| MMV665794 | Probe-like | 680 ± 50 | 90 ± 10 | 90 ± 5 |

| MMV666693 | Drug-like | 730 ± 150 | 40 ± 6 | 20 ± 2 |

| MMV011438 | Probe-like | 820 ± 160 | 50 ± 5 | 130 ± 20 |

| MMV007384 | Probe-like | 870 ± 180 | 100 ± 7 | 190 ± 20 |

| MMV396794 | Drug-like | 870 ± 200 | 180 ± 20 | 60 ± 6 |

| MMV000448 | Probe-like | 1000 ± 280 | 50 ± 5 | 350 ± 40 |

| MMV007591 | Probe-like | 1150 ± 150 | 920 ± 170 | 840 ± 400 |

| MMV666079 | Probe-like | 1460 ± 180 | 210 ± 30 | 260 ± 20 |

| MMV666687 | Probe-like | 1660 ± 210 | 270 ± 50 | 190 ± 8 |

| MMV007224 | Probe-like | 1980 ± 180 | 320 ± 20 | 270 ± 20 |

| MMV666686 | Probe-like | 2060 ± 260 | 450 ± 90 | 360 ± 30 |

| Epoxomicin | Positive control | 3.8 ± 0.2 | NDc | ND |

Gametocytocidal activity was measured using alamarBlue, a fluorescent oxidoreduction indicator of gametocyte metabolic activity. The IC50 values were obtained from dose-response curves calculated from normalized percent activity values and log10-transformed concentrations (see Fig. 3S in the supplemental material). Epoxomicin and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

In vitro antimalarial activity against parasites in asexual stages was evaluated using the SYBR green assay.

ND, not determined.

Fluorescence microscopy.

A Zeiss Axio Imager M1 microscope with a ×100/1.4-numerical-aperture oil immersion objective and an AxioCam MRm digital camera was used to image live parasites as described previously with minor modifications (8). Briefly, control (untreated), parasites treated with IPP alone, drug-treated parasites, and drug-treated parasites supplemented with 200 μM IPP D10-ACPL-GFP were incubated with 100 nM MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (Life Technologies) for 15 min at 37°C. Parasites were washed once with complete medium, and 0.25 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) was added to each condition immediately before imaging. The final figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CS2.

RESULTS

Identification of compounds that act on the apicoplast.

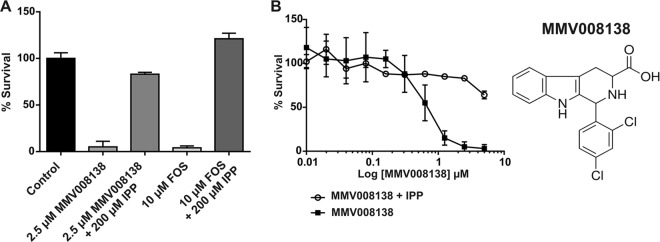

We used reversal of growth inhibition by IPP supplementation to interrogate the Malaria Box to identify compounds that have a mechanism of action that targets the apicoplast (8). From the 400 compounds tested, only the drug-like compound MMV008138 met our criteria of >95% growth inhibition at 5 μM for the compound alone and >60% growth recovery in the presence of inhibitor and 200 μM IPP, as detailed in Materials and Methods. MMV008138 showed at least 85% recovery of growth inhibition in the presence of IPP (Fig. 1A) when retested at 2.5 μM, indicating that this compound interferes with the function of the apicoplast as its mechanism of action. As expected, growth inhibition by FOS was 100% reversed by IPP supplementation. The complete data set listing growth inhibition at 5 μM for all the inhibitors tested, as well as the respective growth recovery in the presence of IPP, is available online (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

(A) MMV008138 at 2.5 μM showed at least 85% recovery of growth inhibition in the presence of 200 μM IPP after 72 h of incubation starting at ring stage. FOS was used as the positive control, as its inhibition is reversed by IPP supplementation. (B) Dose-dependent activity and growth recovery of MMV008138 in the presence of 200 μM IPP after 72 h of incubation. All experiments were performed using the P. falciparum Dd2 strain.

We determined that MMV008138 has an IC50 of 350 nM for the Dd2 strain (Table 1). We observed >85% growth recovery at concentrations up to 2.5 μM MMV008138 and 200 μM IPP, but only ∼70% growth recovery was observed at 5 μM MMV008138 and 200 μM IPP in the Dd2 strain (Fig. 1B), which may indicate off-target effects at high concentrations. To avoid potential off-target effects, all of the following studies were performed at concentrations of ≤2.5 μM. We also noted that the kinetics of MMV008138 inhibition resembled that of FOS activity (Table 1, compare the 72- and 96-h IC50s) (29–31). For comparison, we used DOX, which blocks protein translation in the apicoplast and shows a pronounced delayed-death phenotype (Table 1). Next, we decided to test MMV008138 against a FOS-resistant (FOSr) strain to investigate DXR as the potential molecular target. The resistance in the FOSr is due to an increase in the copy number of the Pfdxr gene, which encodes the enzyme targeted by FOS, allowing the parasite to overcome FOS-mediated inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis (22). Intriguingly, whereas FOS showed a 4-fold increase in the IC50 for the FOSr, relative to its parental strain Dd2, MMV008138 exhibited no increase in its IC50 against FOSr (Table 1, compare Dd2 and FOSr IC50s at 72 h).

TABLE 1.

In vitro activity (IC50) of DOX, FOS, and MMV008138 against asexual stages in different P. falciparum strainsa

| Compound | IC50 (nM) against: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dd2 |

NF54 |

D10-ACPL-GFP at 72 h | FOSr parasites at 72 h | |||

| 72 h | 96 h | 72 h | 96 h | |||

| DOX | >4,500 | 900 ± 180 | 2,370 ± 410 | 380 ± 60 | NDb | ND |

| FOS | 880 ± 70 | 430 ± 50 | 980 ± 60 | ND | 1,610 ± 160 | 3,330 ± 150 |

| MMV008138 | 350 ± 50 | 180 ± 30 | 300 ± 10 | ND | 370 ± 30 | 250 ± 10 |

Data shown are mean ± SD.

ND, not determined.

T. gondii is an apicomplexan parasite that, like P. falciparum, harbors an apicoplast that is essential for survival of the parasite. T. gondii causes toxoplasmosis in humans and can be life-threatening to immunocompromised individuals. Currently, antifolates form the basis of chemotherapy against both primary and secondary (recurrent) infection by T. gondii. Antifolate therapy is effective in limiting the growth of the acute tachyzoite stage but does not cure chronic infection. New drugs with different modes of action are, therefore, highly desirable for this pathogen as well. We tested MMV008138 against T. gondii, but no effect on the growth of the parasite was observed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This lack of activity may be due to the lack of transport of MMV008138, which is similar to previous observations using FOS. While T. gondii relies on the MEP pathway for isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis, the parasite is insensitive to high concentrations of FOS due to the lack of drug uptake at the level of the parasite plasma membrane (7).

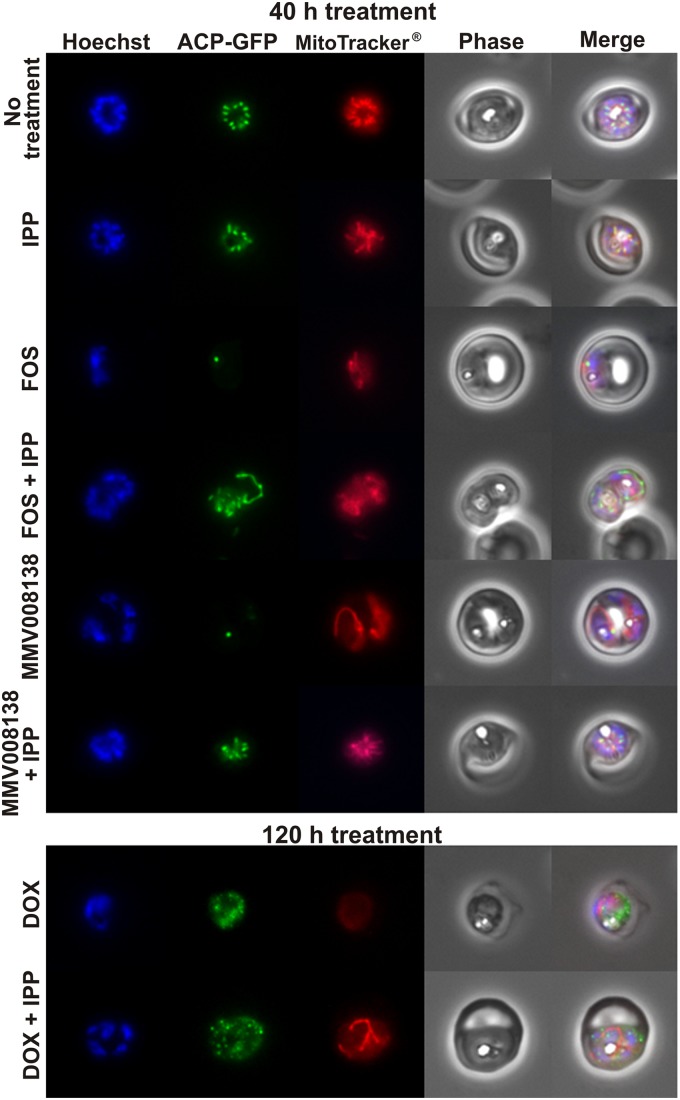

Effect of MMV008138 on apicoplast development.

To investigate the effect of MMV008138 on apicoplast development, we used transgenic P. falciparum cell line D10-ACPL-GFP to visualize the apicoplast (21). In this line, green fluorescent protein (GFP) is targeted to the lumen of the organelle, and its developmental changes along the intraerythrocytic cycle are readily observed. Microscopic analysis showed that the apicoplast elongation and division process was arrested in MMV008138-treated parasites. A single stunted apicoplast was present at a point where controls showed a well-developed tubular apicoplast or an organelle that already had given rise to multiple daughters. This pattern was indistinguishable from that of parasites treated with FOS (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). We also costained cells with MitoTracker, which accumulates in the mitochondria of living cells and is dependent on the mitochondrial membrane potential. We noted diminished labeling of the mitochondrion in both FOS- and MMV008138-treated parasites. A diminished membrane potential is consistent with the role of the apicoplast isoprenoid pathway in ubiquinone biosynthesis. It has been demonstrated that FOS inhibits ubiquinone biosynthesis (17, 32). Ubiquinones participate in the electron transport chain, and their biosynthesis relies on the MEP pathway to provide precursors for the isoprene side chain that anchors them into the inner membrane of the mitochondria. Importantly, the addition of 200 μM IPP rescued both apicoplast development and mitochondrial membrane potential in FOS- and MMV008138-treated parasites (Fig. 2), and this recovery was also observed at 1 μM and 350 nM MMV008138 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). As mentioned above, the effect of DOX treatment on apicoplast development was not observed until the following intraerythrocytic cycle, explaining the slow action of this drug (11). As expected, 40 h of DOX treatment did not affect apicoplast development at this early time point (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material), but the inhibition of apicoplast elongation was observed after 120 h of treatment (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S5C). In contrast, IPP supplementation restored the mitochondrial membrane potential but not apicoplast morphology in DOX-treated parasites. The fact that MMV008138 was fully rescued by IPP suggests a metabolic function for its target, potentially in IPP biosynthesis.

FIG 2.

Wide-field epifluorescence microscopy for the nucleus (Hoechst), apicoplast (ACP-GFP), and mitochondria (MitoTracker), comparing schizonts in untreated control parasites, FOS-treated parasites (10 μM), FOS-treated parasites (10 μM) in the presence of IPP (200 μM), MMV008138-treated parasites (2.5 μM), and MMV008138-treated parasites (2.5 μM) in the presence of IPP (200 μM) after 40 h of treatment. Parasites were treated with DOX (2 μM) in the presence of IPP (200 μM) for 120 h, since inhibition of apicoplast elongation was not observed at 40 h. Additional microscopic fields from each condition can be found in the supplemental material (see Fig. S5A, B, and C in the supplemental material).

Gametocytocidal activity among the Malaria Box compounds.

In our efforts to elucidate the mechanisms of action of compounds within the Malaria Box, we also evaluated their activities against other stages of the life cycle of the parasite. We decided to probe the Malaria Box collection for gametocytocidal activity, since new transmission-blocking antimalarials are needed and the gametocytocidal potentials of the Malaria Box compounds have not been evaluated to date. We identified a set of 22 compounds that showed >85% inhibition of gametocyte viability at 5 μM as assayed by alamarBlue. The complete data for all compounds are available online (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). From the set of 22 active compounds, 18 compounds acted in a clear dose-dependent manner, and 12 of them showed IC50s of <1 μM (Table 2; see also Fig. S3). At a 5 μM concentration, MMV008138 did not have activity against late-stage gametocytes (see Data Set S1). The set of 18 compounds was tested in asexual intraerythrocytic stages against drug-resistant and drug-sensitive parasites. Three compounds, MMV000248, MMV006172, and MMV019555, showed midnanomolar IC50s in late-stage gametocytes and low-nanomolar IC50s in asexual stages (Table 2). An IC50 of 3.8 nM was obtained for epoxomicin, a compound for which gametocytocidal activity had been reported previously (28) (Table 2; see also Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

MMV008138 inhibits apicoplast elongation.

The apicoplast is indispensable for parasite survival and is unique to the parasite. The apicoplast is already a well-established and clinically used target for antibiotics in malaria and toxoplasmosis therapy (4). The apicoplast harbors hundreds of proteins, and there are likely numerous additional targets to be identified and exploited (4, 5, 33, 34). Recently, it was demonstrated that parasites can survive in vitro without the apicoplast when IPP is supplied at 200 μM. A reversal of growth inhibition by IPP supplementation was proposed as a method for potentially identifying compounds targeting apicoplast function (8). Here, we used the IPP supplementation assay to interrogate Malaria Box compounds that target the apicoplast in order to establish their mechanisms of action, and we identified MMV008138 as a new antiapicoplast lead (Table 1). Interestingly, we noted that the mechanism of action of MMV008138 is more like that of FOS than that of DOX. In general, drugs like DOX, which target apicoplast genome replication, transcription, protein translation, posttranslation modification, or protein turnover, exhibit a delayed-death phenotype (9–15). The kinetics of MMV008138 provided circumstantial support for the hypothesis that this drug acts more directly on the metabolism of the organelle than through interference with its biogenesis.

More directly, we showed that MMV008138 inhibited apicoplast elongation and disturbed the mitochondrial membrane potential and that these phenotypes were reversed by the presence of IPP (Fig. 2). FOS also showed inhibition of apicoplast elongation, as reported previously (7), and we have reported here that this phenotype can be reversed by IPP supplementation. A potential mechanism by which FOS prevents apicoplast elongation could be through inhibition of the isoprenoid modification of the tRNA on the adenine bases, which is essential for binding to the mRNA-ribosome complex and ensures translational integrity (33, 35). Four tRNAs in Plasmodium are predicted to be isoprenylated in the apicoplast (33). However, no studies have been reported so far that directly demonstrate tRNA isoprenylation in Plasmodium. Furthermore, FOS also disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential, which was expected, as FOS inhibits ubiquinone biosynthesis (17, 32). The rescue of apicoplast elongation by IPP supplementation was not observed in parasites treated with DOX (Fig. 2), similar to chloramphenicol (8), which inhibits protein synthesis in the apicoplast by targeting the ribosomes. This suggests that DOX and MMV008138 act on different targets and that MMV008138 does not interfere with protein synthesis.

Altogether, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that MMV008138 may have its molecular target within the MEP pathway; therefore, we also tested this compound against FOSr parasites. As mentioned above, the resistance in this parasite strain is due to an increase in the copy number of the Pfdxr gene (22). The FOSr strain exhibited no change in its IC50 for MMV008138 compared with that in its parental strain Dd2, suggesting that DXR is most likely not the molecular target (Table 1). Since the apicoplast is indispensable for apicomplexan parasites and is an attractive drug target, we tested MMV008138 against T. gondii, another important human pathogen, but it was inactive, similar to FOS, perhaps due to poor transport (7). Our efforts to identify the potential molecular target(s) for MMV008138 in P. falciparum may also help to establish the basis of its lack of activity in T. gondii.

It has been shown that antibiotics targeting the apicoplast, including FOS, do not affect late-stage gametocytes (20), and we observed that MMV008138 also did not affect late-stage gametocytes. This lack of activity was expected, since the apicoplast does not grow during gametocytogenesis, but others have noted that the mitochondrion undergoes remarkable morphological development during gametocytogenesis (36), which requires an active MEP pathway to supply IPP and DMAPP for ubiquinone biosynthesis. The low activities of FOS and MMV008138 against late-stage gametocytes might then be attributed to either (i) poor transport or (ii) prior biosynthesis and storage of the needed isoprenoids.

Due to its short half-life in plasma, FOS is not suitable for monotherapy; however, combination therapy studies in humans revealed success in maintaining total parasite clearance when FOS was used with artesunate or clindamycin (37–43). Thus far, our results indicate that MMV008138 affects apicoplast function and that its molecular target may differ from current antiapicoplast drugs, like FOS. Whether a compound like MMV008138 could comprise a new monotherapy or a useful adjunct to other antimalarials will depend upon many factors, including pharmacokinetic parameters.

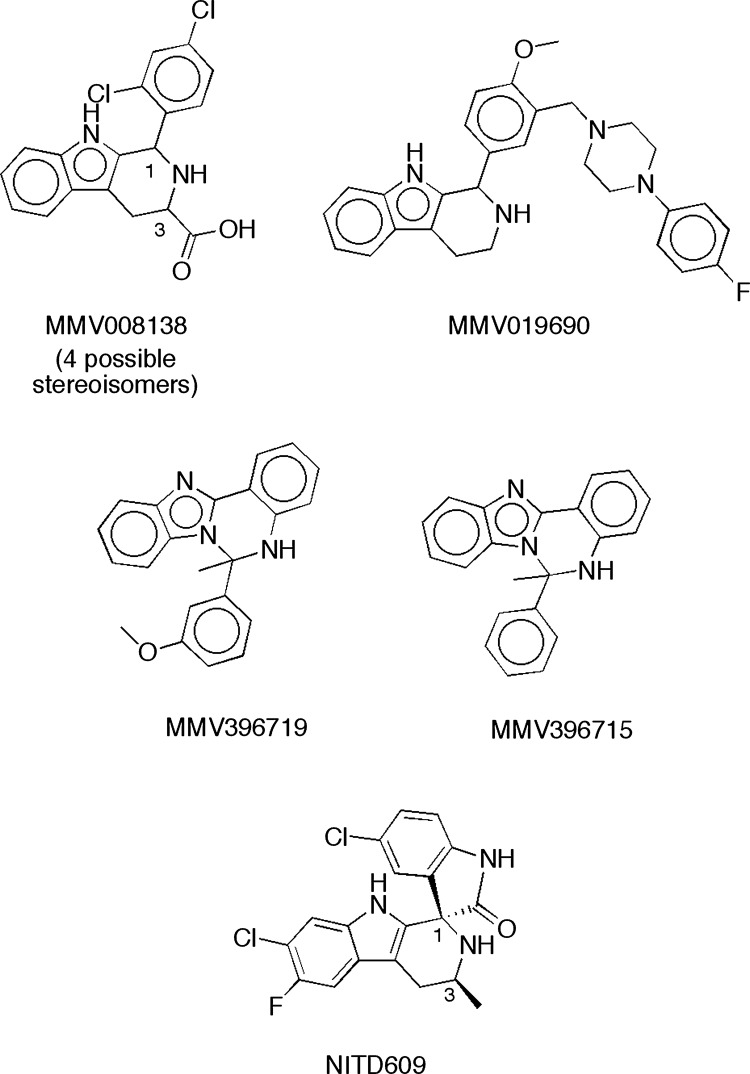

Structure-activity relationship of MMV008138.

The most notable structural features of MMV008138 are its pipecolic acid and tetrahydro-β-carboline moieties. A review of the 400 compounds in the Malaria Box revealed that only MMV008138 possessed both of these functionalities. One other tetrahydro-β-carboline (MMV019690) and two related structures (MMV396719 and MMV396715) (Fig. 3) were identified among the 400 compounds, with only MMV019690 possessing the 1-aryl substituent present in MMV008138. Since none of the three other related structures possessed antiapicoplast activity, we conclude that the appropriate 1-aryl group and 3-carboxylic acid (i.e., pipecolic acid) moiety contribute to antiapicoplast activity. Interestingly, the clinical candidate, NITD609, has a scaffold structure that is very similar to that of MMV008138 and is currently in human clinical trials as a monotherapy for malaria (44–47). In addition to possessing the 1-aryl-tetrahydro-β-carboline, this potential antimalarial features a transposed pipecolic acid moiety in the form of a spiroamide and a methyl group in place of the carboxy group of MMV008138 (Fig. 3). It should be noted that MMV008138 is present in the Malaria Box as an unspecified mixture of four stereoisomers that differ in their configurations at C-1 and C-3. After we confirmed that MMV008138 was specifically targeting the apicoplast, MMV008138 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (again, an unspecified mixture of stereoisomers), and the repeat assay results matched those of the MMV sample. Of these possible stereoisomers, the (1R,3R)-stereoisomer of MMV008138 coincidentally provides a structure that closely mimics that of NITD609 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). NITD609 targets PfATPase4, a plasma membrane Na+ efflux pump (44), and it is active against gametocyte stages (45). Is the (1R,3R)-stereoisomer of MMV008138 present in the Malaria Box, and if so, does it have activity similar to that of NITD609? At this point, we cannot address this question since, as mentioned, the low gametocytocidal activity of MMV008138 may be due to poor transport in late-stage gametocytes.

FIG 3.

Structures of MMV008138, three other tetrahydro-β-carbolines or close analogs in the Malaria Box, and clinical candidate NITD609.

It is also too early to know what off-target activities MMV008138 might possess. Tetrahydro β-carbolines comprise a large group of natural and synthetic indole alkaloids. These compounds are of great interest due to their diverse biological activities, and they possess a broad spectrum of pharmacological properties, including sedative, anxiolytic, hypnotic, anticonvulsant, antitumor, antiviral, and antiparasitic as well as antimicrobial activities (48). Additionally, their molecular targets span from the inhibition of topoisomerase, monoamine oxidase, and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases to interaction with benzodiazepine receptors and 5-hydroxy serotonin receptors. However, to the best of our knowledge, MMV008138 has no other biological or enzymatic activities reported beyond its antimalarial activity in asexual intraerythrocytic stages (29–31).

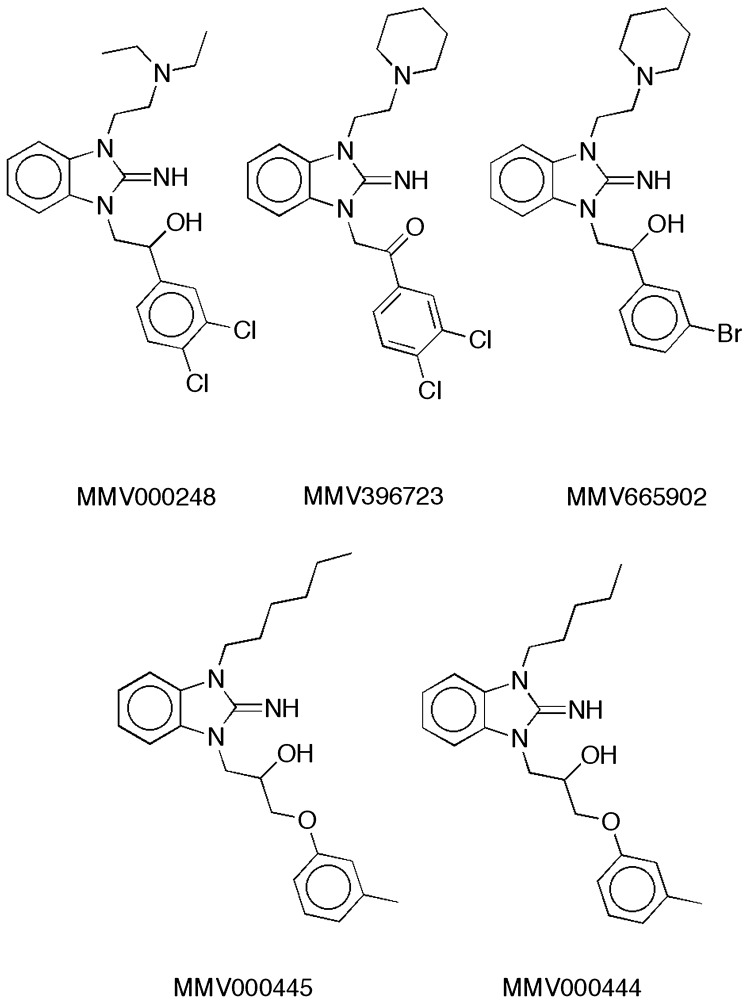

New potential leads for transmission-blocking development.

Currently, primaquine is the only drug that is active against late-stage gametocytes, and only a small set of new transmission-blocking drugs are in clinical trials (49), supporting the urgent need for new leads against late-stage gametocytes. Therefore, we decided to interrogate the Malaria Box against late-stage gametocytes not only as a complementary assay to study their mechanisms of action but also to identify new gametocytocidal leads. Twelve compounds with IC50s of <1 μM against late-stage gametocytes were identified. Three compounds, MMV000248, MMV006172, and MMV019555, showed midnanomolar IC50s in late-stage gametocytes and low-nanomolar IC50s in asexual stages (Table 2).

Among these three compounds, two basic pharmacophores were identified, the benzimidazole imine scaffold and the 9-aminoacridine/9-amino-tetrahydroacridine scaffold. MMV000248 (Fig. 4) is a promising drug-like compound that showed the best overall potency in late-stage gametocytes and asexual stages (Table 2). It possesses the bicyclic guanidine or benzimidazole imine scaffold, which is also present in four other compounds in the Malaria Box (Fig. 4). MMV396723 and MMV665902 contain pendant tertiary amine moieties that are similar to that of MMV000248. Three of the four compounds (MMV665902, MMV000445, and MMV000444) also resemble MMV000248 in bearing a secondary alcohol embedded in a 2- to 4-atom linker connecting the endocyclic nitrogen of the imidazole imine to an aromatic ring. The lack of confirmed gametocytocidal activity of these four compounds, combined with 10- to 20-fold increases in their previously reported asexual stage IC50s (2), is quite striking. Overall, these data indicate strict structural requirements for both gametocytocidal and asexual-stage activity within this scaffold (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

MMV000248 and related benzimidazole imine structures in the Malaria Box. The IC50s for MMV396723 (∼1.25 μM), MMV665902 (∼1 μM), MMV000445 (∼1.135 μM), and MMV000444 (∼1.25 μM) in asexual intraerythrocytic stages were previously reported and can be found in the ChEMBL database (see https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chemblntd).

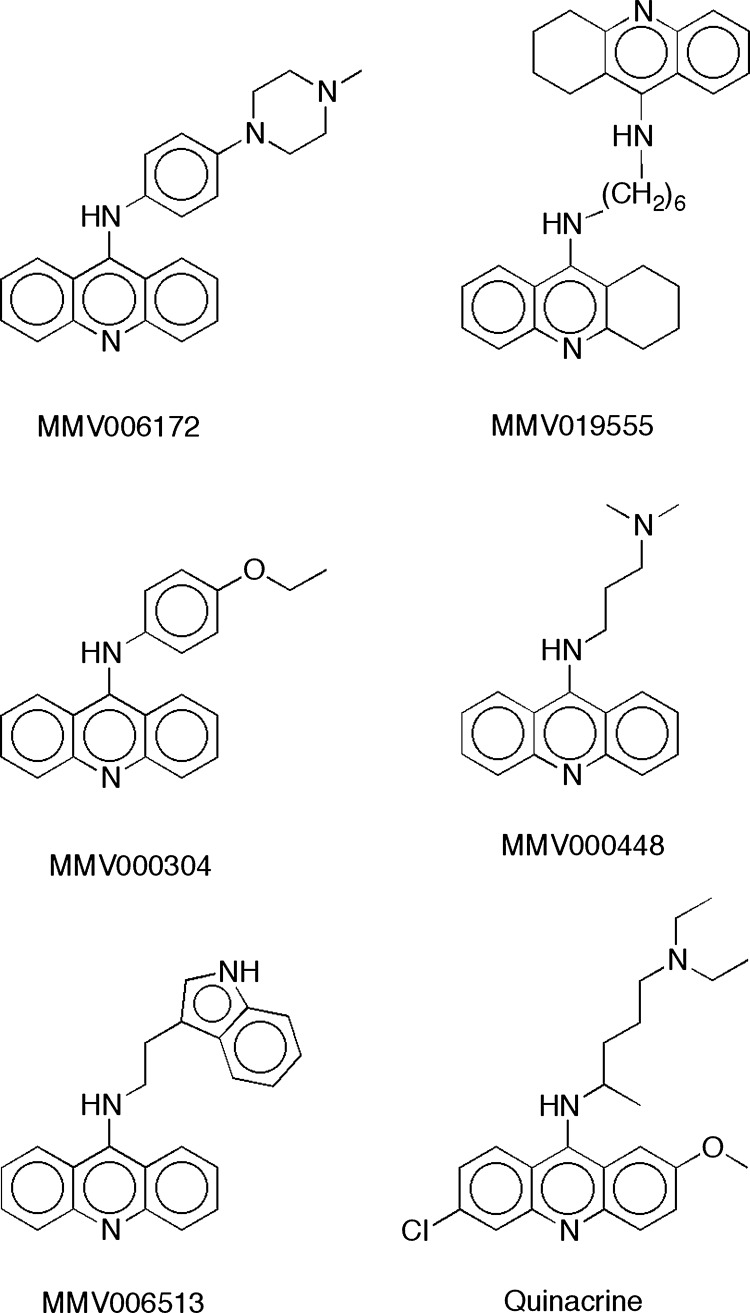

MV006172 and MMV019555 possess the 9-aminoacridine and 9-amino-tetrahydroacridine scaffolds, respectively, known to be antimalarial pharmacophores (50). MV006172 was shown to have moderate activity against the liver stage of Plasmodium yoelii (30), and this compound was also found to bind to the recombinant human α-2C adrenergic receptor (51). MMV019555 is a dimeric molecule that was originally explored as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (52). A search of the Malaria Box revealed three other 9-aminoacridines (MMV000304, MMV000448, and MMV006513) and no additional 9-amino-tetrahydroacridines (Fig. 5). Interestingly, MMV006172 bears a close resemblance to the three other 9-aminoacridines and quinacrine, which is a known potent antimalarial that is active against intraerythrocytic asexual stages of the chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum Dd2 strain (53) and inactive against P. falciparum gametocytes (54, 55). The asexual-stage potency of MMV006172, MMV019555, and MMV000448 (Table 2) may stem from their structural resemblance to quinacrine (IC50, 5 to 10 nM [53]). Like quinacrine, both of these compounds feature a 5- to 7-atom tether to a basic amine moiety. The three other 9-aminoacridines in Fig. 4 either feature a shorter tether or lack a pendant basic amine. However, since quinacrine is inactive against P. falciparum gametocytes, this structural motif is clearly not sufficient for gametocytocidal activity.

FIG 5.

MMV006172, MMV019555, three related 9-aminoacridines in the Malaria Box, and quinacrine.

In conclusion, we identified one promising drug-like compound, MMV000248, showing activity against both asexual and sexual intraerythrocytic stages at low and midnanomolar values, respectively, and is a potential multistage lead that could be developed to cure malaria and stop its transmission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds from the Fralin Life Science Institute, the Jeffress Memorial Trust of Virginia (J-1058), and the Virginia Commonwealth Health Research Board (208-03-12) (to M.B.C.). J.D.B. is the recipient of a scholarship from the National Science Foundation S-STEM project (DUE-0850198). B.S. is a GRA distinguished investigator, and his work on the apicoplast is supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI64671 and AI084415).

We thank Michael Klemba and Priscilla Krai for their assistance with fluorescence microscopy and valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01500-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burrows JN. 2012. Antimalarial drug discovery: where next? Future Med. Chem. 4:2233–2235. 10.4155/fmc.12.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spangenberg T, Burrows JN, Kowalczyk P, McDonald S, Wells TNC, Willis P. 2013. The open access Malaria Box: a drug discovery catalyst for neglected diseases. PLoS One 8:e62906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA, Garcia-Bustos JF, Diagana TT, Gamo FJ, Guy RK. 2012. Global phenotypic screening for antimalarials. Chem. Biol. 19:116–129. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman CD, McFadden GI. 2013. Targeting apicoplasts in malaria parasites. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 17:167–177. 10.1517/14728222.2013.739158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dooren GG, Striepen B. 2013. The algal past and parasite present of the apicoplast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67:271–289. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odom AR, Van Voorhis WC. 2010. Functional genetic analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase gene. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 170:108–111. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair SC, Brooks CF, Goodman CD, Sturm A, McFadden GI, Sundriyal S, Anglin JL, Song Y, Moreno SN, Striepen B. 2011. Apicoplast isoprenoid precursor synthesis and the molecular basis of fosmidomycin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Exp. Med. 208:1547–1559. 10.1084/jem.20110039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh E, DeRisi JL. 2011. Chemical rescue of malaria parasites lacking an apicoplast defines organelle function in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001138. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittlin S, Ekland E, Craft JC, Lotharius J, Bathurst I, Fidock DA, Fernandes P. 2012. In vitro and in vivo activity of solithromycin (CEM-101) against Plasmodium species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:703–707. 10.1128/AAC.05039-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl EL, Rosenthal PJ. 2007. Multiple antibiotics exert delayed effects against the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3485–3490. 10.1128/AAC.00527-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl EL, Shock JL, Shenai BR, Gut J, DeRisi JL, Rosenthal PJ. 2006. Tetracyclines specifically target the apicoplast of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3124–3131. 10.1128/AAC.00394-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman CD, Su V, McFadden GI. 2007. The effects of anti-bacterials on the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 152:181–191. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aminake MN, Schoof S, Sologub L, Leubner M, Kirschner M, Arndt HD, Pradel G. 2011. Thiostrepton and derivatives exhibit antimalarial and gametocytocidal activity by dually targeting parasite proteasome and apicoplast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1338–1348. 10.1128/AAC.01096-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathore S, Sinha D, Asad M, Bottcher T, Afrin F, Chauhan VS, Gupta D, Sieber SA, Mohmmed A. 2010. A cyanobacterial serine protease of Plasmodium falciparum is targeted to the apicoplast and plays an important role in its growth and development. Mol. Microbiol. 77:873–890. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fichera ME, Roos DS. 1997. A plastid organelle as a drug target in apicomplexan parasites. Nature 390:407–409. 10.1038/37132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl EL, Rosenthal PJ. 2008. Apicoplast translation, transcription and genome replication: targets for antimalarial antibiotics. Trends Parasitol. 24:279–284. 10.1016/j.pt.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassera MB, Gozzo FC, D'Alexandri FL, Merino EF, del Portillo HA, Peres VJ, Almeida IC, Eberlin MN, Wunderlich G, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Kimura EA, Katzin AM. 2004. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway is functionally active in all intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51749–51759. 10.1074/jbc.M408360200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Turbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK, Soldati D, Beck E. 1999. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285:1573–1576. 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delves M, Plouffe D, Scheurer C, Meister S, Wittlin S, Winzeler EA, Sinden RE, Leroy D. 2012. The activities of current antimalarial drugs on the life cycle stages of Plasmodium: a comparative study with human and rodent parasites. PLoS Med. 9:e1001169. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peatey CL, Leroy D, Gardiner DL, Trenholme KR. 2012. Anti-malarial drugs: how effective are they against Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes? Malar. J. 11:34. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waller RF, Reed MB, Cowman AF, McFadden GI. 2000. Protein trafficking to the plastid of Plasmodium falciparum is via the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 19:1794–1802. 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharia NV, Sidhu AB, Cassera MB, Westenberger SJ, Bopp SE, Eastman RT, Plouffe D, Batalov S, Park DJ, Volkman SK, Wirth DF, Zhou Y, Fidock DA, Winzeler EA. 2009. Use of high-density tiling microarrays to identify mutations globally and elucidate mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biol. 10:R21. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harinantenaina L, Bowman JD, Brodie PJ, Slebodnick C, Callmander MW, Rakotobe E, Randrianaivo R, Rasamison VE, Gorka A, Roepe PD, Cassera MB, Kingston DG. 2013. Antiproliferative and antiplasmodial dimeric phloroglucinols from Mallotus oppositifolius from the Madagascar dry forest. J. Nat. Prod. 76:388–393. 10.1021/np300750q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. 2004. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1803–1806. 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gubbels MJ, Li C, Striepen B. 2003. High-throughput growth assay for Toxoplasma gondii using yellow fluorescent protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:309–316. 10.1128/AAC.47.1.309-316.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacRae JI, Dixon MW, Dearnley MK, Chua HH, Chambers JM, Kenny S, Bottova I, Tilley L, McConville MJ. 2013. Mitochondrial metabolism of sexual and asexual blood stages of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Biol. 11:67. 10.1186/1741-7007-11-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka TQ, Williamson KC. 2011. A malaria gametocytocidal assay using oxidoreduction indicator, alamarBlue. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 177:160–163. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czesny B, Goshu S, Cook JL, Williamson KC. 2009. The proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin has potent Plasmodium falciparum gametocytocidal activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4080–4085. 10.1128/AAC.00088-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL, Vanderwall DE, Green DV, Kumar V, Hasan S, Brown JR, Peishoff CE, Cardon LR, Garcia-Bustos JF. 2010. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 465:305–310. 10.1038/nature09107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meister S, Plouffe DM, Kuhen KL, Bonamy GM, Wu T, Barnes SW, Bopp SE, Borboa R, Bright AT, Che J, Cohen S, Dharia NV, Gagaring K, Gettayacamin M, Gordon P, Groessl T, Kato N, Lee MC, McNamara CW, Fidock DA, Nagle A, Nam TG, Richmond W, Roland J, Rottmann M, Zhou B, Froissard P, Glynne RJ, Mazier D, Sattabongkot J, Schultz PG, Tuntland T, Walker JR, Zhou Y, Chatterjee A, Diagana TT, Winzeler EA. 2011. Imaging of Plasmodium liver stages to drive next-generation antimalarial drug discovery. Science 334:1372–1377. 10.1126/science.1211936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plouffe D, Brinker A, McNamara C, Henson K, Kato N, Kuhen K, Nagle A, Adrian F, Matzen JT, Anderson P, Nam TG, Gray NS, Chatterjee A, Janes J, Yan SF, Trager R, Caldwell JS, Schultz PG, Zhou Y, Winzeler EA. 2008. In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high-throughput screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9059–9064. 10.1073/pnas.0802982105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cassera MB, Merino EF, Peres VJ, Kimura EA, Wunderlich G, Katzin AM. 2007. Effect of fosmidomycin on metabolic and transcript profiles of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway in Plasmodium falciparum. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 102:377–383. 10.1590/S0074-02762007000300019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ralph SA, Van Dooren GG, Waller RF, Crawford MJ, Fraunholz MJ, Foth BJ, Tonkin CJ, Roos DS, McFadden GI. 2004. Tropical infectious diseases: metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:203–216. 10.1038/nrmicro843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim L, McFadden GI. 2010. The evolution, metabolism and functions of the apicoplast. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365:749–763. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Meer JY, Hirsch AK. 2012. The isoprenoid-precursor dependence of Plasmodium spp. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29:721–728. 10.1039/c2np20013a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamoto N, Spurck TP, Goodman CD, McFadden GI. 2009. Apicoplast and mitochondrion in gametocytogenesis of Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot. Cell 8:128–132. 10.1128/EC.00267-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Missinou MA, Borrmann S, Schindler A, Issifou S, Adegnika AA, Matsiegui PB, Binder R, Lell B, Wiesner J, Baranek T, Jomaa H, Kremsner PG. 2002. Fosmidomycin for malaria. Lancet 360:1941–1942. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11860-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiesner J, Borrmann S, Jomaa H. 2003. Fosmidomycin for the treatment of malaria. Parasitol. Res. 90(Suppl):S71–76. 10.1007/s00436-002-0770-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiesner J, Henschker D, Hutchinson DB, Beck E, Jomaa H. 2002. In vitro and in vivo synergy of fosmidomycin, a novel antimalarial drug, with clindamycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2889–2894. 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2889-2894.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borrmann S, Adegnika AA, Matsiegui PB, Issifou S, Schindler A, Mawili-Mboumba DP, Baranek T, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Kremsner PG. 2004. Fosmidomycin-clindamycin for Plasmodium falciparum infections in African children. J. Infect. Dis. 189:901–908. 10.1086/381785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borrmann S, Adegnika AA, Moussavou F, Oyakhirome S, Esser G, Matsiegui PB, Ramharter M, Lundgren I, Kombila M, Issifou S, Hutchinson D, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Kremsner PG. 2005. Short-course regimens of artesunate-fosmidomycin in treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3749–3754. 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3749-3754.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borrmann S, Issifou S, Esser G, Adegnika AA, Ramharter M, Matsiegui PB, Oyakhirome S, Mawili-Mboumba DP, Missinou MA, Kun JF, Jomaa H, Kremsner PG. 2004. Fosmidomycin-clindamycin for the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1534–1540. 10.1086/424603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Na-Bangchang K, Ruengweerayut R, Karbwang J, Chauemung A, Hutchinson D. 2007. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of fosmidomycin monotherapy and combination therapy with clindamycin in the treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum malaria. Malar. J. 6:70. 10.1186/1475-2875-6-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spillman NJ, Allen RJ, McNamara CW, Yeung BK, Winzeler EA, Diagana TT, Kirk K. 2013. Na(+) regulation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum involves the cation ATPase PfATP4 and is a target of the spiroindolone antimalarials. Cell Host Microbe 13:227–237. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Pelt-Koops JC, Pett HE, Graumans W, van der Vegte-Bolmer M, van Gemert GJ, Rottmann M, Yeung BK, Diagana TT, Sauerwein RW. 2012. The spiroindolone drug candidate NITD609 potently inhibits gametocytogenesis and blocks Plasmodium falciparum transmission to anopheles mosquito vector. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3544–3548. 10.1128/AAC.06377-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rottmann M, McNamara C, Yeung BK, Lee MC, Zou B, Russell B, Seitz P, Plouffe DM, Dharia NV, Tan J, Cohen SB, Spencer KR, Gonzalez-Paez GE, Lakshminarayana SB, Goh A, Suwanarusk R, Jegla T, Schmitt EK, Beck HP, Brun R, Nosten F, Renia L, Dartois V, Keller TH, Fidock DA, Winzeler EA, Diagana TT. 2010. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 329:1175–1180. 10.1126/science.1193225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeung BK, Zou B, Rottmann M, Lakshminarayana SB, Ang SH, Leong SY, Tan J, Wong J, Keller-Maerki S, Fischli C, Goh A, Schmitt EK, Krastel P, Francotte E, Kuhen K, Plouffe D, Henson K, Wagner T, Winzeler EA, Petersen F, Brun R, Dartois V, Diagana TT, Keller TH. 2010. Spirotetrahydro beta-carbolines (spiroindolones): a new class of potent and orally efficacious compounds for the treatment of malaria. J. Med. Chem. 53:5155–5164. 10.1021/jm100410f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao R, Peng W, Wang Z, Xu A. 2007. beta-Carboline alkaloids: biochemical and pharmacological functions. Curr. Med. Chem. 14:479–500. 10.2174/092986707779940998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dechy-Cabaret O, Benoit-Vical F. 2012. Effects of antimalarial molecules on the gametocyte stage of Plasmodium falciparum: the debate. J. Med. Chem. 55:10328–10344. 10.1021/jm3005898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdes AF. 2011. Acridine and acridinones: old and new structures with antimalarial activity. Open Med. Chem. J. 5:11–20. 10.2174/1874104501105010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoglund IP, Silver S, Engstrom MT, Salo H, Tauber A, Kyyronen HK, Saarenketo P, Hoffren AM, Kokko K, Pohjanoksa K, Sallinen J, Savola JM, Wurster S, Kallatsa OA. 2006. Structure-activity relationship of quinoline derivatives as potent and selective alpha(2C)-adrenoceptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 49:6351–6363. 10.1021/jm060262x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlier PR, Han YF, Chow ES, Li CP, Wang H, Lieu TX, Wong HS, Pang YP. 1999. Evaluation of short-tether bis-THA AChE inhibitors. A further test of the dual binding site hypothesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7:351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pou S, Winter RW, Nilsen A, Kelly JX, Li Y, Doggett JS, Riscoe EW, Wegmann KW, Hinrichs DJ, Riscoe MK. 2012. Sontochin as a guide to the development of drugs against chloroquine-resistant malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3475–3480. 10.1128/AAC.00100-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Covell G, Coatney GR, Field JW, Singh J. 1955. Chemotherapy of malaria. Monogr. Ser. World Health Organ. 27:1–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Powell RD, Tigertt WD. 1968. Drug resistance of parasites causing human malaria. Annu. Rev. Med. 19:81–102. 10.1146/annurev.me.19.020168.000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.